Abstract

Summary

This analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2008 data describes the prevalence of risk factors for osteoporosis and the proportions of men and postmenopausal women age 50 years and older who are candidates for treatment to lower fracture risk, according to the new Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX)-based National Osteoporosis Foundation Clinician’s Guide.

Introduction

It is important to update estimates of the proportions of the older US population considered eligible for pharmacologic treatment for osteoporosis for purposes of understanding the health care burden of this disease.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study of the NHANES 2005–2008 data in 3,608 men and women aged 50 years and older. Variables in the analysis included race/ethnicity, age, lumbar spine and femoral neck bone mineral density, risk factor profiles, and FRAX 10-year fracture probabilities.

Results

The prevalence of osteoporosis of the femoral neck ranged from 6.0% in non-Hispanic black to 12.6% in Mexican American women. Spinal osteoporosis was more prevalent among Mexican American women (24.4%) than among either non-Hispanic blacks (5.3%) or non-Hispanic whites (10.9%). Treatment eligibility was similar in Mexican American and non-Hispanic white women (32.0% and 32.8%) and higher than it was in non-Hispanic black women (11.0%). Treatment eligibility among men was 21.1% in non-Hispanic whites, 12.6% in Mexican Americans, and 3.0% in non-Hispanic blacks.

Conclusions

Nineteen percent of older men and 30% of older women in the USA are at sufficient risk for fracture to warrant consideration for pharmacotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

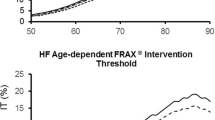

The 2008 National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) Clinician’s Guide indicates who among men and women aged 50 years and older should be considered for treatment for osteoporosis [1]. Briefly, eligibility is based on a prior spine or hip fracture, a lumbar spine or femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) T-score ≤−2.5, or, among those with low bone mass or osteopenia (T-score −1 to −2.5) who have no prior spine or hip fracture, a 10-year probability ≥3% for a hip fracture or ≥20% for any major osteoporotic fracture (defined as spine, hip, proximal humerus, or distal forearm fracture) according to the World Health Organization’s fracture prediction tool, FRAX® [2]. We previously estimated the potential impact of this NOF guidance on osteoporosis treatment patterns in the USA using the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) data then available, which covered the time period, 1988–1994 [3]. To make these estimates, it was necessary to simulate some missing risk factor information as well as data on spine BMD, which had not been collected in NHANES III.

During the interval between NHANES III (1988–1994) and the most recently available NHANES data (2005–08), several changes have occurred that are likely to alter estimates of the numbers of men and women potentially eligible for pharmacotherapy by the NOF Guide. First, secular changes in femoral neck BMD have occurred between the two survey periods [4]. Secular changes have also occurred in the prevalence of two of the clinical risk factors used in FRAX, body mass index (BMI) and smoking, and these changes also differ in direction and magnitude by race and sex [4]. In addition, in the newer NHANES survey, spine BMD and all of the risk factor variables needed to calculate FRAX scores were measured, obviating the need to use simulated data. Because these factors could significantly alter the numbers of men and women potentially eligible for treatment, it seemed appropriate to update the estimates. Thus, the objective of this study was to use NHANES 2005–08 data to describe the current prevalence of clinical risk factors used in FRAX and to revise earlier estimates of the proportions of US men and women who are eligible for consideration for pharmacotherapy according to the 2008 NOF Guide [1].

Methods

Sample

The NHANES are conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to assess the health and nutritional status of large representative cross-sectional samples of the non-institutionalized, US civilian population. The present study was based on data collected in NHANES 2005–2008 via household interviews and direct standardized physical examinations conducted in specially equipped mobile examination centers [5]. All procedures were approved by the NCHS Ethics Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

NHANES 2005–2008 was designed to provide reliable estimates for three race/ethnic groups (by self-report): non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and Mexican Americans. The present study was limited to men and postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older without missing data for height, weight, femur neck BMD, and BMD for at least two lumbar vertebrae, as required for valid lumbar spine T-scores according to recommendations of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry [6]. Persons with missing data for other risk factors used in the study were assumed not to have the risk factor, consistent with the approach used in calculating FRAX scores (http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/index.htm).

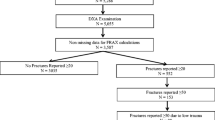

A total of 7,532 adults aged 50 years and older were eligible to participate in NHANES 2005–2008. Of these, 5,288 (70%) were interviewed and 5,055 (67%) were examined, of whom 3,608 met inclusion criteria for this study. They represent 48% of the eligible adults aged 50 years and older, 68% of those who were interviewed and 71% of those who were interviewed and examined.

Variables

Bone mineral density

The anterior–posterior lumbar spine and femoral neck were measured with Hologic QDR 4500A fan-beam densitometers (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA) using Apex version 3.0 software (lumbar spine) or Discovery version 12.4 software (femur neck) as described elsewhere [5, 6]. The left hip was scanned unless there was a history of previous fracture or surgery, and scanning was done in the fast mode. Rigorous quality control (QC) programs were employed, which included the use of anthropomorphic phantoms and review of each QC and respondent scan at a central site (Department of Radiology of the University of California, San Francisco), using standard radiologic techniques and study-specific protocols developed for the NHANES [7, 8]. Bone density T-scores were calculated as (respondent’s BMD − reference group mean BMD)/reference group standard deviation [SD]). The reference group for the femoral neck consisted of 409 non-Hispanic white women aged 20–29 years from NHANES III [9], while the reference group for the lumbar spine consisted of 30-year-old white females from the dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry manufacturer reference database [10]. Osteoporosis and low bone mass (osteopenia) were defined according to World Health Organization criteria [11].

Anthropometry

Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.01 kg using an electronic load cell scale, and standing height was measured with a fixed stadiometer. BMI was calculated as body weight (kilograms) divided by height (meters squared).

Previous fracture

Previous fractures were based on self-reported fractures that occurred after age 20 years. Fractures that occurred at any skeletal site were recorded.

Parental history of hip fracture

Parental hip fracture history was based on self-report that the respondents’ biological mother or father had fractured their hip.

Cigarette smoking and high alcohol intake

Cigarette smokers were defined as respondents who self-reported that they currently smoked, while high alcohol users were defined as respondents who self-reported that they usually consumed three or more drinks of alcohol per day to be consistent with the approach used for this variable in the FRAX model.

Use of systemic glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoid use was based on a combination of prescription glucocorticoids for 90+ days (current use) and self-report of having ever taken prednisone or cortisone nearly every day for > =90 days (past use). Respondents showed the containers for all current prescription medications to the interviewer, who recorded the name of the product and the reason and length of usage for each medicine. Medications were assigned standard generic names and four-digit generic codes using the December 2007 Multum Lexicon Drug Database (Cerner Multum Inc, Denver CO; http://www.multum.com/Lexicon.htm). Unless drug class information indicated a topical or ocular form, the following drugs were considered to be systemic glucocorticoids in the present analysis: cortisone acetate, budesonide, dexamethasone, hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, prednisolone, prednisolone acetate, prednisolone acetate and sodium phosphate, prednisone, and triamcinolone.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Persons with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) were defined as those who self-reported having been told by a doctor that they had RA and were either currently taking prescription antirheumatic drugs or glucocorticoid medications or self-reported having ever taken prednisone or cortisone nearly every day for > = 1 month. Prescription antirheumatic medications were defined using the antirheumatic drug classification in the Lexicon Plus proprietary database (Cerner Multum Inc) plus selected other medications consisting of gold sodium thiomalate, penicillamine, auranofin, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, etanercept, azathioprine, leflunomide, sulfasalazine, and chloroquine.

Other causes of secondary osteoporosis

These were not included in this analysis because they do not affect FRAX scores when BMD is in the algorithm [2].

Menopausal status

As proposed by McKinlay et al. [12], women were considered postmenopausal if they met at least one of the following conditions: (a) over 55 years of age, (b) had a hysterectomy, (c) had both ovaries removed, or (d) had no period in the past 12 months and reported that menopause or a hysterectomy was the reason for having no periods in the past 12 months.

Estimated 10-year fracture probability

Probabilities were calculated for hip fracture and for major osteoporotic fractures combined (hip, spine, proximal humerus or distal forearm fracture) using the recently revised (version 3.0) FRAX algorithm [13]. The 10-year probability of a hip fracture was estimated for non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks using the algorithm for “whites” and “blacks,” respectively [14]. “Other Hispanics” and “Mexican Americans” were analyzed as “Hispanic” in the FRAX algorithm; the remaining “Other Races” category was analyzed as Asian since internally available NHANES records on ancestry revealed that most were Asian. However, in all subsequent data analyses, race/ethnic groups other than non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Mexican American were combined as “Other Races” in order to be consistent with sampling domains used in the NHANES surveys. In addition, there were too few Asians in the sample to permit statistically reliable estimates for this subgroup alone.

Definition of treatment eligibility

Postmenopausal women and men aged 50 years and older who met any of the following criteria were defined as eligible for treatment based on the new NOF Guide [1]:

-

1.

Had a self-reported hip or spine fracture after age 20 years;

-

2.

Had a femoral neck or spine BMD T-score <−2.5 SD; or

-

3.

Had a femoral neck T-score between −1 and −2.5 SD with a 10-year hip fracture probability of ≥3% or major fracture probability of ≥20%.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted with PC-SAS (version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and SUDAAN (version 10.0, Research Triangle Institute, NC). All analyses used sample weights and took into account the complex design of the survey. All age-standardized estimates were calculated using the age distribution from the US Census 2000 population. Differences in treatment eligibility or in risk factors by race/ethnicity or sex were tested using multiple linear (for continuous variables) or logistic (for categorical variables) regression. Logistic regression was used to test for age trends in the prevalence of treatment-eligible individuals. The estimated number of persons meeting the NOF treatment guidelines was calculated by multiplying the crude prevalence meeting the guideline by the Current Population Survey estimate of the number of non-institutionalized civilian adults aged 50 years and older at the midpoint of 2005–2008 [15].

Results

The proportions of men and women with spinal and femoral neck BMD in the low bone mass and osteoporotic categories are shown in Table 1. Mexican American women had higher prevalences of low spinal bone mass (41.4%) and osteoporosis (24.4%) than did non-Hispanic black women (28.0% and 5.3%, respectively) and a higher prevalence of spinal osteoporosis than did non-Hispanic white women (24.4% and 10.9%, respectively). Prevalences of low spinal bone mass and osteoporosis in Mexican American men (28.1% and 4.6%, respectively) were also greater than those in non-Hispanic white or non-Hispanic black men. The prevalences of low bone mass and osteoporosis at the femoral neck in Mexican American women were close to those of non-Hispanic whites (Table 1). There were too few Mexican American men with osteoporosis to make a valid race/ethnic comparison.

The prevalence of the other risk factors for fracture used in FRAX is also shown in Table 1 by sex and, where sample size permits, by race group and age. The other most common risk factor was “a previous fracture at any skeletal site after age 20 years.” This risk factor was more prevalent in non-Hispanic white men and women (40.0% and 37.2%, respectively) than in Mexican Americans (24.0% and 27.4%, respectively) or non-Hispanic blacks (22.1% and 22.9%, respectively). Current smoking and alcohol use (more than or equal to three drinks per day) were intermediate in prevalence, ranging from about one fifth to one third of men and less than half that many in women. Mexican American men had higher alcohol use than non-Hispanic white or non-Hispanic black men (34.9%, 18.5%, and 18.9%). Prevalences of the other risk factors were generally low, roughly 10% or less.

The percentages of participants meeting NOF criteria for consideration for treatment, by age, sex, and race/ethnicity, are shown in Table 2 and by sex and race/ethnicity only in Fig. 1. Overall, 30.8% (13.8 million) of postmenopausal women and 19.3% (6.6 million) men of all races, aged 50 years and older, in the USA met the NOF criteria for treatment. Among women, 32.8% (11.6 million) of non-Hispanic whites, 32.0% (0.5 million) of Mexican Americans, and 11.0% (0.4 million) of non-Hispanic blacks met the NOF criteria for treatment. Among men, 21.1% (5.8 million) of non-Hispanic whites, 12.6% (0.2 million) of Mexican Americans, and 3.0% (0.1 million) of non-Hispanic blacks met the criteria. As expected, the percentages eligible increased significantly with age in the total population and in non-Hispanic whites. Age trends could not be tested in other race/ethnic groups.

Age-adjusted percent of men and women aged 50 years and older, by race/ethnicity, who are candidates for treatment under the NOF Guide. Solid bars are non-Hispanic blacks (NHB), hatched bars are Mexican Americans (MexAm), stippled bars are non-Hispanic whites (NHW), and crosshatched bars are all race groups (All)

We also estimated the proportion of non-Hispanic white men and women aged 65 years and older who met the NOF criteria for treatment eligibility, in order to allow comparisons with published estimates from large prospective studies of older white men and women in the USA. Among non-Hispanic whites aged 65+ years, 31.8% (standard error (SE) = 2.5) and 51.7% (SE = 1.8) of men and women, respectively, met the NOF criteria.

The percent of low bone mass participants with no prior spine or hip fracture but meeting NOF criteria for treatment is shown in Table 3 because this is the group whose eligibility, according to the NOF Guide, is directly dependent upon their FRAX score. Among these individuals, a higher percentage of men than women had a FRAX score high enough to qualify for treatment; this difference was statistically significant in non-Hispanic whites (32.6% and 27.7%, respectively). To assess the possible basis for this, we examined and compared the age-adjusted prevalences of FRAX risk factors in non-Hispanic white men and women with low bone mass (Table 4). The men had significantly lower 10-year major fracture risk scores, but modestly higher 10-year hip fracture risk scores than the women (not statistically significant). The men had a higher prevalence of significant alcohol use than the women, and more men than women had two clinical risk factors for fracture (25.6% vs. 14.1%). Thus, differences in risk factor profiles appear to account for the higher treatment eligibility among low bone mass men compared with women.

Discussion

Over 20 million non-institutionalized older adults in the USA qualify for consideration for osteoporosis treatment by the NOF Guide. This number corresponds to about one third of women and one fifth of men aged 50 years and older in the USA. These and other prevalence estimates herein should supersede earlier estimates from NHANES III [3] because they are more current and because all variables used in these analyses were measured directly. In the earlier estimates, spine BMD data and some clinical risk factor data were not available and were therefore simulated [3].

Treatment eligibility differed by race/ethnicity, with non-Hispanic blacks having the lowest prevalence. Among men, more non-Hispanic whites than Mexican Americans qualified for treatment, whereas among women, the proportions qualifying were similar. The prevalence of treatment eligibility by the NOF Guide criteria has been assessed in other largely Caucasian cohorts in the USA, including women aged 65 years and older in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) [16], men aged 65 years older in Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) study [17], and men and women aged 50 and older in the Framingham Study [18]. Prevalences of treatment eligibility in the Framingham cohort, 41% in women and 17% in men, were fairly close to those observed in non-Hispanic whites in this study. Prevalence in men in MrOS (34%) was in line with that of the non-Hispanic white men aged 65+ years in this study (31.8%), but the prevalence in women in SOF (72%) was higher than that seen in non-Hispanic white women aged 65+ years in this study (−51.7%). This difference could be due to secular trends in femur BMD, since femur BMD data in SOF were measured in 1988–1990 and femur BMD may have increased in the older US population since that time [4]. In contrast, BMD measurements in MrOS were made in the early 2000s. It is now recognized that the majority of fractures originate not among men and women with osteoporosis but in the much larger candidate pool with low bone mass [19]. Among subjects with low bone mass of the spine or hip, 28.2% of men and 24.6% of women qualified for treatment. In non-Hispanic whites, the only group that was large enough to make a race/ethnic gender comparison, eligibility was significantly greater in men than in women (32.6% vs. 27.7%).This may reflect the finding that men with low bone mass are more likely than women to have multiple clinical risk factors. These analyses reveal the high yield with respect to treatment eligibility that can be expected from performing FRAX risk assessments in men and women with low bone mass. Equally important, however, is the observation that osteoporosis treatment would not appear to be indicated in the majority of individuals with low bone mass.

While it is the prevailing view that osteoporosis is most common in non-Hispanic whites, intermediate in Mexican Americans, and least common in non-Hispanic blacks, we note herein that the prevalence of lumbar spine osteoporosis in Mexican American men and women was more than double that in non-Hispanic white men and women. With respect to femoral neck osteoporosis, the prevalence did not differ significantly in Mexican American and non-Hispanic white women; the limited sample size did not permit a comparison in men. There is evidence that osteoporosis is a growing problem in Hispanics. Based on a recent cross-sectional analysis, the age-related decline in femoral neck BMD was greater in Hispanic than in white or black men [20]. Looker et al. reported that, unlike results seen for other race/ethnic groups, femoral neck BMD did not increase in Mexican American men between NHANES III and 2005–2008 [4]. It has also been reported that hip fracture rates in Hispanics residing in CA doubled between 1983 and 2000 [21] and that fracture rates among Hispanics are expected to increase markedly over the interval between 2005 and 2050, based on US Census data [22]. We did not observe a significant increase in the prevalence of femoral neck osteoporosis in Mexican Americans between NHANES III and 2005–2008. Unfortunately, methodological differences do not allow us to comment on secular changes in spinal osteoporosis.

The prevalence of femoral neck osteoporosis appears to have declined in non-Hispanic white men and women between NHANES III and 2005–2008, consistent with Looker’s observation that BMD in women and to a lesser degree also in men has increased [4]. The decline in osteoporosis may be attributable to more effective prevention and treatment strategies or other factors; however, osteoporosis remains undertreated. A recent study estimated that in 2008, only 6.9% of US women aged 45 years and older took bisphosphonates, the most common treatment for osteoporosis, at a compliance level of at least 50% [23]. This number (6.9%) is small in comparison to the proportion of older US women eligible by the NOF criteria. There is no reason to believe that appropriate treatment is more prevalent in men [24].

Strengths of this study include the fact that the data were derived from a recent nationally representative sample, and thus are likely to reflect the current treatment eligibility status of the US population. In addition, all risk factor data were measured, so that data simulations were not needed for any variable. Limitations include the inability to obtain statistically reliable estimates by race/ethnicity for several risk factors due to relatively small sample size and the fact that the NHANES data included only non-institutionalized subjects. We were not able to examine secular trends in FRAX risk scores and treatment eligibility based on the NOF Guide because of uncertainty about the comparability of the measured risk factors in the present study with the spine BMD and selected risk factor data that were simulated in our earlier report [3]. Finally, treatment eligibility may be underestimated particularly in Mexican American women because of their high prevalence of spinal low bone mass, given that the FRAX calculator does not currently include BMD of the spine.

In conclusion, roughly one third of postmenopausal women and one fifth of older men in the USA are at sufficient risk for fracture to warrant consideration for pharmacotherapy, involving about one third of women and one fifth of men aged 50 years and older. Of special concern is the high prevalence of low bone mass and osteoporosis in the Mexican American population, which now meets or exceeds levels observed in non-Hispanic whites. Recognition of the numbers eligible for consideration for treatment helps identify a goal by which to assess the impact or success of prevention and treatment efforts in the USA.

References

National Osteoporosis Foundation (2008) Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. National Osteoporosis Foundation, Washington, D.C., pp 1–36

Kanis J (2008) Assessment of osteoporosis at the primary health-care level. WHO Collaborating Centre, University of Sheffield, Sheffield

Dawson-Hughes B, Looker AC, Tosteson AN, Johansson H, Kanis JA, Melton LJ 3rd (2010) The potential impact of new National Osteoporosis Foundation guidance on treatment patterns. Osteoporos Int 21:41–52

AC Looker AC LMI, LG Borrud, JA Shepherd (2011) Changes in femur neck bone density in US adults between 1988–1994 and 2005–2008: demographic patterns and possible determinants. Osteoporosis International 22: doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1623-0

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NCHS (1999–2011) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville

Baim S, Binkley N, Bilezikian JP, Kendler DL, Hans DB, Lewiecki EM, Silverman S (2008) Official Positions of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry and executive summary of the 2007 ISCD Position Development Conference. J Clin Densitom 11:75–91

Centers of Disease Control and Prevention NCHS (2006) National Health and Nutrition Survey: body composition procedure manual. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NCHS (2007) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) procedure manual. U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville

Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Calvo MS, Harris TB, Heyse SP, Johnston CC Jr, Lindsay R (1998) Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int 8:468–489

Kelly TJ (1990) Bone mineral density reference databases for American men and women. J Bone Miner Res 5(Suppl 1):S249

Kanis JA, Melton LJ 3rd, Christiansen C, Johnston CC, Khaltaev N (1994) The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 9:1137–1141

McKinlay SM (1994) Issues in design, measurement, and analysis for menopause research. Exp Gerontol 29:479–493

Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, Dawson-Hughes B, Melton LJ 3rd, McCloskey EV (2010) The effects of a FRAX revision for the USA. Osteoporos Int 21:35–40

Dawson-Hughes B, Tosteson AN, Melton LJ 3rd, Baim S, Favus MJ, Khosla S, Lindsay RL (2008) Implications of absolute fracture risk assessment for osteoporosis practice guidelines in the USA. Osteoporos Int 19:449–458

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NCHS (2010) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey NHANES response rates and CPS totals. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, MD. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/response_rates_CPS.htm

Donaldson MG, Cawthon PM, Lui LY, Schousboe JT, Ensrud KE, Taylor BC, Cauley JA, Hillier TA, Black DM, Bauer DC, Cummings SR (2009) Estimates of the proportion of older white women who would be recommended for pharmacologic treatment by the new U.S. National Osteoporosis Foundation Guidelines. J Bone Miner Res 24:675–680

Donaldson MG, Cawthon PM, Lui LY, Schousboe JT, Ensrud KE, Taylor BC, Cauley JA, Hillier TA, Dam TT, Curtis JR, Black DM, Bauer DC, Orwoll ES, Cummings SR (2010) Estimates of the proportion of older white men who would be recommended for pharmacologic treatment by the new US National Osteoporosis Foundation guidelines. J Bone Miner Res 25:1506–1511

Berry SD, Kiel DP, Donaldson MG, Cummings SR, Kanis JA, Johansson H, Samelson EJ (2010) Application of the National Osteoporosis Foundation Guidelines to postmenopausal women and men: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int 21:53–60

Siris ES, Miller PD, Barrett-Connor E, Faulkner KG, Wehren LE, Abbott TA, Berger ML, Santora AC, Sherwood LM (2001) Identification and fracture outcomes of undiagnosed low bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment. JAMA 286:2815–2822

Araujo AB, Travison TG, Harris SS, Holick MF, Turner AK, McKinlay JB (2007) Race/ethnic differences in bone mineral density in men. Osteoporos Int 18:943–953

Zingmond D (2004) Increasing hip fracture incidence in California Hispanics, 1983 to 2000. Osteoporos Int 15:603–610

Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A (2007) Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res 22:465–475

Siris ES, Pasquale MK, Wang Y, Watts NB (2011) Estimating bisphosphonate use and fracture reduction among US women aged 45 years and older, 2001–2008. J Bone Miner Res 26:3–11

Jaglal SB, Weller I, Mamdani M, Hawker G, Kreder H, Jaakkimainen L, Adachi JD (2005) Population trends in BMD testing, treatment, and hip and wrist fracture rates: are the hip fracture projections wrong? J Bone Miner Res 20:898–905

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This material is based on work supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, under agreement No. 58-1950-7-707. Any opinions, findings, conclusion, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dawson-Hughes, B., Looker, A.C., Tosteson, A.N.A. et al. The potential impact of the National Osteoporosis Foundation guidance on treatment eligibility in the USA: an update in NHANES 2005–2008. Osteoporos Int 23, 811–820 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1694-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1694-y