Abstract

Purpose

Posterior shoulder dislocation is often associated with bone defects. Surgical treatment is often necessary to address these lesions. The aim of the present systematic review was to analyse the available literature concerning bone block procedures in the treatment of bone deficiencies following posterior dislocation. In addition, the methodology of the articles has been evaluated through the Coleman methodology score.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was performed using the keywords “posterior shoulder instability”, “posterior shoulder dislocation”, “bone loss”, “bone defect”, “bone block”, and “bone graft” with no limit regarding the year of publication. All English-language articles were evaluated using the Coleman methodology score.

Results

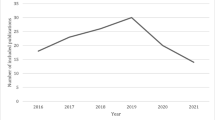

Fifty-four articles were identified, and 13 articles met inclusion criteria. The initial cohort included 208 shoulders, and 182 were reviewed at an average follow-up of 72.7 months (±55.2). The average Coleman score was 57.2 (±8.0). The most lacking domains were the size of study population, the type of study, and the procedure for assessing outcomes. All the articles showed an increase in the outcome scores. Radiographic evaluation revealed degenerative changes such as osteoarthritis and graft lysis in most of the series.

Conclusions

This review confirms the lack of studies with good methodological quality. However, bone grafting is a reliable option since significant improvement in all scores is reported. Although a low incidence of recurrence is generally described, there are concerns that the results may deteriorate over time as evidenced by graft lysis and glenohumeral osteoarthritis in up to one-third of patients.

Level of evidence

Systematic review, Level IV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Posterior shoulder instability is an uncommon injury, accounting for approximately 3 % of all shoulder dislocations, with a reported prevalence of 1.1 per 100,000 per year [16, 24, 29, 30]. The most common injury pattern of posterior shoulder instability is the detachment of the posteroinferior labrum and an additional capsular stretching that can lead to insufficiency of the posterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (PIGHL) [31]. The presence of additional bony lesions such as posterior bony Bankart, glenoid erosion, posterior glenoid dysplasia, or reversed Hill–Sachs lesion must be investigated with accurate imaging evaluation [1], because these lesions can contribute to recurrent instability when not appropriately recognised.

The treatment of posterior shoulder instability must address the damage of the soft tissue structures as well as bony damage. The treatment of bone defects is still debated with several surgical options having been described with a posterior glenoid bone block, glenoid osteotomy, or capsule–tendinous transpositions. Moreover, the outcomes of these procedures and the possible intraoperative or post-operative complications must be studied since much controversy surrounds the best treatment option.

The present systematic review is the first one that analyses the available literature concerning bone block procedures in the treatment of bone deficiencies following posterior dislocation. The aim of this study was to address the controversial aspects and to discuss indications, outcomes, and complications with different surgical treatment options. To achieve this goal, the methodology of the available literature has been investigated, as weak methodology limits the value of the reported results. This evaluation was performed using the modified Coleman score, which has been demonstrated as a reliable tool [7].

Materials and methods

The following databases were accessed on 10 July 2014: PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez/); Ovid (http://www.ovid.com); Cochrane Reviews (http://www.cochrane.org/reviews/); and Google Scholar (www.googlescholar.com). A comprehensive search following the PRISMA guidelines was performed using various combinations of the keywords “posterior shoulder instability”, “bone loss”, “bone defect”, and “bone block”, with no limit regarding the year of publication. http://www.cochrane.org/reviews/.

Two authors screened each publication according to the abstract text, excluding articles if the abstract was not available and if the language was non-English. In addition, the reference lists of the included studies were manually searched to include articles not identified in the initial search. Twenty-eight full-text articles were identified. Randomised controlled trials (RCT) and prospective case series are the most relevant designs; however, studies with a high level of evidence (Level I or Level II) were not available for this topic. Given the limitations of the available level of evidence, no limitations on the level of evidence were set, follow-up duration, or the number of patients enrolled. Prospective and retrospective studies reporting clinical and radiographic outcomes of bone block procedures in patients with bone deficiencies after posterior shoulder dislocation or recurrent posterior dislocation were included in the study, while reviews, technical notes, and case reports were excluded [4–6, 9, 15, 18, 19, 23, 28, 32, 37]. At the end of this selection and after excluding technical notes and case reports, 13 articles were evaluated.

The articles were evaluated according to the Coleman methodology score (CMS) [7]. The Coleman methodology score consists of 10 criteria in two parts (part A and part B), which assess the methodological quality of scientific studies. Part A is divided into seven subsections with a total score of 60, whereas part B is divided into three subsections with a total score of 40 out of 42. Each of the 13 included articles was assessed for all 10 criteria to give a final score ranging from 0 to 100. A perfect score of 100 represents a study design that largely avoids the influence of chance, various biases, and confounding factors. Although no cut-off for the definition of high- or low-quality studies has been previously set, a total score greater than 65 is usually accepted as the inferior limit for a high-quality study [11, 34].

Results

Patient demographics

Thirteen articles were included and evaluated according to the Coleman guidelines. Two articles included arthroscopic treatment [2, 35], while 11 articles included open techniques [8, 12–14, 20, 24–27, 33, 36]. The original series of patients reported by Martinez et al. [24] and Goosens et al. [14] were re-evaluated at longer-term follow-up by Martinez et al. [25] and Meuffels et al. [26], respectively. Patient demographics are summarised in Table 1. The initial cohort included 208 shoulders (191 patients). One-hundred and fifty-one patients were males, while 40 were females. The average age was 35.8 ± 10.8 years. Inclusion criteria included posterior shoulder dislocation [8, 12, 13, 24, 25, 33] or recurrent posterior instability [2, 14, 20, 26, 27, 35, 36], and 182 shoulders (out of 208) were reviewed at an average follow-up of 72.7 ± 55.2 months.

Coleman methodology score

All studies were evaluated following the Coleman score criteria. All data are summarised in Table 1. The average methodological score was 57.2 ± 8.0, indicating weak quality. Concerning section A, the average score for the first item (study size) was 1.5, for the second item (mean follow-up) was 4.2, for the third (number of different surgical procedures) was 8.5, for the fourth was 0.8 (type of study), for the fifth (diagnostic certainty) was 3.8, for the sixth (description of surgical procedure) was 4.8, and for the seventh (description of post-operative rehabilitation) was 5.4. Concerning section B, the average score for the first item (outcome criteria) was 9.4, the score for the second item (procedure for assessing outcomes) was 6.0, while the score for the third item (description of subject selection process) was 12.7. The most lacking domains were the size of study population, the type of study, and the procedure for assessing outcome.

Surgical procedures, outcomes, and complications

Seven studies were focused on glenoid bone loss, which was treated with bone grafting using open or arthroscopic procedures [2, 14, 20, 26, 27, 35, 36]. Five studies reported the outcomes of fresh allograft to treat humeral head defects [8, 12, 13, 24, 25]. One study reported the outcomes of different surgical options (open reduction, McLaughlin procedure, rotational osteotomy, total shoulder arthroplasty, and iliac crest graft or humeral head allograft) to address the bone defect on the humeral side [33]. Outcomes are summarised in Table 1. Most common outcome measurement scores included Walch–Duplay score [3, 35, 36], Constant–Murley score [9, 13, 14, 24, 25, 33], Rowe score [15, 26, 33, 35], or VAS score [15, 26, 27, 35]. Average rate of recurrent instability and apprehension at final follow-up was 9.5 ± 20.2 %, whereas average rate of radiographic complications, including osteoarthritis, bone graft lysis, humeral head necrosis, or collapse, at final follow-up was 31.8 ± 29.4 %.

Discussion

Three major findings emerged from the present review. Firstly, the weak methodology of the available literature must be highlighted. Previous studies have demonstrated that great caution is required when interpreting the outcomes of studies having low methodological quality [17]. The average CMS of the analysed literature was 57.2. These data are similar to what has been reported in a systematic review on the tenotomy and tenodesis of the long head of the biceps brachii where the average Coleman score was 58 [35]. In the present review, the most critical domains were the size of the study population, the type of study, and the procedure for assessing outcomes. The first aspect is related to the pathology itself. Large series of surgical treatment of posterior shoulder instability associated with severe bone defects are uncommon. The second aspect is common throughout the literature. All articles with the exception of the one by Gerber [12] are retrospective cohort studies with low level of evidence. The last aspect is related to the methodology of the studies. In most cases, critical information such as the extraction and the acquisition of the data or the completion of the outcomes tools is poorly reported. These important methodological limitations make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions and highlight the need for additional research in this area.

However, this study, which is the first systematic review on the issue, with clear methodology and two independent reviewers, highlights two additional findings that may be relevant in clinical practice. First of all, long-term studies show a clear deterioration of the outcomes over time. This was demonstrated in the two studies, which re-evaluated the outcomes of previous series at longer follow-up [24, 26]. The comparison of the outcomes at intermediate and final follow-up revealed clear deterioration of all examined parameters (Table 1, n.1). Secondly, the majority of the studies reported significant radiographic complications varying from graft lysis to humeral head osteonecrosis and collapse leading to glenohumeral osteoarthritis in up to one-third of patients (Table 1).

Finally, recurrent instability was a less common finding when compared to radiographic complications.

Posterior shoulder instability is rare and accounts for approximately 2–5 % all glenohumeral joint instability [22, 26, 29, 30]. Bone defects are more common on the humeral side than the glenoid rim for posterior dislocations compared to anterior dislocations. McLaughlin was the first to describe osteochondral defects involving the anterior aspect of the humeral head [22]. Recent reports have shown that 42 % of patients after posterior dislocations had a large (volume of defect >1.5 cm3) reverse Hill–Sachs lesion [29]. The presence of a humeral head bone defect significantly increases the risk of recurrence [29]. Similarly, glenoid bone loss is a risk factor for recurrence. This has been clearly demonstrated in cadaveric and biomechanical studies. Bryce et al. [3] and Wirth et al. [38] have shown that posterior translation is highly sensitive to small degrees of posterior glenoid defects or retroversion. Posterior humeral head translation increased significantly with 5° of posterior glenoid bone loss, which equates to approximately 2.5° of glenoid retroversion [3]. Based on these data, it seems reasonable to address the bony lesions in addition to repairing the soft tissue damage. Historically, it was believed that bony defects involving less than 20 % of the articular surface could be managed non-operatively [10]. However, since reverse Hill–Sachs lesions usually involve more of the articular surface compared with Hill–Sachs lesions [29], there was general agreement that bony lesions greater than 10 % of the articular surface may have be clinically significant and may require intervention [29]. A recent systematic review highlighted the lack of precise guidelines regarding which bone defects should be treated with bony procedures and the correlation between the extent of bone loss and the risk of recurrent dislocation [21]. Bone block procedures have been proposed to treat both the defects at the glenoid and humeral sites. Most of series in the literature are focused of open treatment using autografts and allografts and report variable rates of clinical and radiographic complications.

Four studies focused on open bone grafting to address posterior glenoid defects.

Levigne et al. [20] described a technique of open bone block (with associated capsulorraphy in 80 % of cases) in a series of 29 patients (31 shoulders). Clinical and radiographic complications were observed, including persistent apprehension in critical position in 13 % of patients, slightly limited mobility in internal rotation in 29 %, persistent pain in 39 % (mostly during sports), and partial lysis of the bone block in 23 %. In addition, three patients required removal of the screws. Similarly, Servien et al. [36], in a series of 20 patients treated with open iliac bone block, reported clinical failures for recurrent posterior dislocation or apprehension in three patients and glenohumeral arthritis in two cases.

Gosens et al. [14] reported the results of a similar technique in a series of 11 patients at an average follow-up of 72. Persistent pain was observed in two patients, limited mobility in four, and radiographic resorption of the graft in three cases. The recurrence rate was high (80 %) in patients with additional laxity, and the removal of a screw was necessary in three patients. At longer follow-up (216 months), the same series was reviewed by Meuffels et al. [26] with significant deterioration of all clinical parameters. Eight patients (72 %) had an unstable shoulder, and four of them (36 %) suffered recurrent posterior dislocation. In addition, all patients had radiological signs of osteoarthritis, whereas only four cases (36 %) had osteoarthritis at the time of surgery. Millet et al. [27] described a novel technique of distal tibial allograft to treat posterior glenoid bone loss. The outcomes of this technique were evaluated in two male patients at a minimum follow-up of 24 months. No complications were reported.

Other studies focused on the treatment of bone loss on the humeral side. Gerber et al. [12] were the first to describe the use of humeral head allograft in the treatment of humeral bone defects (at least 40 %) in four patients with posterior dislocation. At an average follow-up of 68 months, two patients reported pain, and one of them suffered humeral head necrosis. More recently, Diklic et al. [8] reported the outcomes of a similar technique in 13 patients (bone defect ranging from 25 to 50 %). Although no patients had recurrent instability, four patients reported persistent pain, and one patient developed osteonecrosis.

Similarly, Martinez et al. [24] reported the results of this series of six patients (bone defect of 40 % of the humeral head volume). At an average follow-up of 62.6 months, two patients reported pain and stiffness with radiographic evidence of collapse of the graft and secondary osteoarthritis. The same series was re-evaluated at longer follow-up (122 months) [25], and three patients out of six had good functional results, because of a third patient who developed osteoarthrosis 8 years after the operation.

Gerber et al. [13] evaluated the outcomes of 22 shoulders having been treated with fresh allograft (17 shoulders) and structural iliac crest autograft (five shoulders) for their humeral head defect (average 43 %). Nineteen patients were reviewed at 128 months (range 60–294 months). Two patients required further prosthetic replacement, four had radiographic signs of advanced osteoarthritis, and mild signs of osteoarthritis were reported in four patients.

Schliemann et al. [33] reported the outcomes of a series of 35 patients treated for locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder at an average follow-up of 55 months. Six patients were treated conservatively, and 29 underwent different surgical procedures (addressing the defect on the humerus) because of an unstable shoulder after close reduction. Patients treated conservatively achieved a better outcome (Constant score of 85 vs. 79). An anatomic reconstruction of the defect and a smaller interval between the injury and the diagnosis led to better results. Radiographic follow-up showed narrowing of the joint space and formation of osteophytes in approximately 68 % of all affected shoulder joints. A decreased acromiohumeral distance was observed in 34 % of the patients.

More recently, arthroscopic procedures of bone grafting have been proposed. Schwartz et al. [35] performed 19 arthroscopic posterior bone blocks on 18 patients with posterior instability. At an average follow-up of 20.5 months, excellent results were reported in nine cases with return to the previous level of sports. Persistent painful shoulder was observed in three cases, instability in one patient, and screw removal was necessary in two patients. Boileau et al. [2] described an all-arthroscopic technique of posterior shoulder stabilisation. To avoid the complications related to screws position and length, the authors used suture anchors for both bone block fixation and capsulolabral repair. At an average follow-up of at least 12 months, fifteen patients were evaluated. None of them had recurrence of instability or apprehension.

To our knowledge, the present systematic review is the first one focusing on the bone block procedures to address bone defects following posterior shoulder instability. However, the study has some limitations. First of all, the investigation is based on a small number of studies that retrospectively report the techniques and outcomes of different surgical procedures. The differences in inclusion criteria concerning acute dislocations and recurrent instability may be a source of bias when analysing outcomes. Furthermore, the analysis of the studies reveals weak methodology (Coleman score of 57.2). Additionally, preoperative data as well as postoperative are not available for all series, making comparison of the outcomes impossible. Finally, despite the use of several databases, using an appropriate combination of keywords, it is possible that some papers may have been inadvertently excluded during our search.

However, there are several notable findings in this review that can help the surgeons in their clinical practice. Patients must be informed about the possible clinical and radiographic complications with signs of bone graft lysis, humeral head necrosis, and joint degeneration, which were reported in around 35 % of patients. The risk of progressive deterioration of the outcomes over time must be taken into account, and patients should be counselled about this prior to surgery.

Conclusion

Humeral and glenoid bone grafting has been advocated to address bony deficiencies after posterior shoulder dislocations. The available literature lacks methodological quality, consisting of retrospective cohort studies based on small series and with poor acquisition and interpretation of the data. According to these aspects, it is hard to draw any definitive conclusion concerning the outcomes. In any case, some aspects must be highlighted when proposing these procedures: the outcomes are generally positive in the short term but tend to deteriorate over time, and the risk of graft lysis and further glenohumeral joint osteoarthritis must be closely followed.

References

Aparicio G, Calvo E, Bonilla L, Espejo L, Box R (2000) Neglected traumatic posterior dislocations of the shoulder: controversies on indications for treatment and new CT scan findings. J Orthop Sci 5:37–42

Boileau P, Hardy MB, McClelland WB Jr, Thélu CE, Schwartz DG (2013) Arthroscopic posterior bone block procedure: a new technique using suture anchor fixation. Arthrosc Tech 2(4):e473–e477

Bryce CD, Davison AC, Okita N, Lewis GS, Sharkey NA, Armstrong AD (2010) A biomechanical study of posterior glenoid bone loss and humeral head translation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 19:994–1002

Charalambous CP, Gullett TK, Ravenscroft MJ (2009) A modification of the McLaughlin procedure for persistent posterior shoulder instability: technical note. 1. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 129(6):753–755

Chen L, Keefe D, Park J, Resnick D (2009) Posterior bony humeral avulsion of glenohumeral ligament with reverse bony Bankart lesion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 18(3):e45–e49

Cicak N (2004) Posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br 86(3):324–332

Coleman BD, Khan KM, Maffulli N, Cook JL, Wark JD (2000) Studies of surgical outcome after patellar tendinopathy: clinical significance of methodological deficiencies and guidelines for future studies. Victorian Institute of Sport Tendon Study Group. Scand J Med Sci Sports 10:2–11

Diklic ID, Ganic ZD, Blagojevic ZD, Nho SJ, Romeo AA (2010) Treatment of locked chronic posterior dislocation of the shoulder by reconstruction of the defect in the humeral head with an allograft. J Bone Joint Surg Br 92(1):71–76

Duey RE, Burkhart SS (2013) Arthroscopic treatment of a reverse Hill–Sachs lesion. Arthrosc Tech 2(2):e155–e159

Finkelstein JA, Waddell JP, O’Driscoll SW, Vincent G (1995) Acute posterior fracture dislocations of the shoulder treated with the Neer modification of the McLaughlin procedure. J Orthop Trauma 9:190–193

Frost A, Zafar MS, Maffulli N (2009) Tenotomy versus tenodesis in the management of pathologic lesions of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii. Am J Sports Med 37(4):828–833

Gerber C, Lambert SM (1996) Allograft reconstruction of segmental defects of the humeral head for the treatment of chronic locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 78(3):376–382

Gerber C, Catanzaro S, Jundt-Ecker M, Farshad M (2014) Long-term outcome of segmental reconstruction of the humeral head for the treatment of locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 23(11):1682–1690

Gosens T, van Biezen FC, Verhaar JA (2001) The bone block procedure in recurrent posterior shoulder instability. Acta Orthop Belg 67(2):116–120

Gupta AK, Chalmers PN, Klosterman E, Harris JD, Provencher MT, Romeo AA (2013) Arthroscopic distal tibial allograft augmentation for posterior shoulder instability with glenoid bone loss. Arthrosc Tech 2(4):e405–e411

Hovelius L (1982) Incidence of shoulder dislocation in Sweden. Clin Orthop Relat Res 166:127–131

Jakobsen RB, Engebretsen L, Slauterbeck JR (2005) An analysis of the quality of cartilage repair studies. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87:2232–2239

Khayal T, Wild M, Windolf J (2009) Reconstruction of the articular surface of the humeral head after locked posterior shoulder dislocation: a case report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 129(4):515–519

Lafosse L, Franceschi G, Kordasiewicz B, Andrews WJ, Schwartz D (2012) Arthroscopic posterior bone block: surgical technique. Musculoskelet Surg 96(3):205–212

Levigne C, Garret J, Walch G (2005) Posterior bone block for posterior instability. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg 6(1):26–35

Longo UG, Rizzello G, Locher J, Salvatore G, Florio P, Maffulli N, Denaro V (2014) Bone loss in patients with posterior gleno-humeral instability: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. Jul 24 [Epub ahead of print]

McLaughlin HL (1952) Posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 24(3):584–590

Martetschläger F, Padalecki JR, Millett PJ (2013) Modified arthroscopic McLaughlin procedure for treatment of posterior instability of the shoulder with an associated reverse Hill–Sachs lesion. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 21(7):1642–1646

Martinez AA, Calvo A, Domingo J, Cuenca J, Herrera A, Malillos M (2008) Allograft reconstruction of segmental defects of the humeral head associated with posterior dislocations of the shoulder. Injury 39(3):319–322

Martinez AA, Navarro E, Iglesias D, Domingo J, Calvo A, Carbonel I (2013) Long-term follow-up of allograft reconstruction of segmental defects of the humeral head associated with posterior dislocation of the shoulder. Injury 44(4):488–491

Meuffels DE, Schuit H, van Biezen FC, Reijman M, Verhaar JA (2010) The posterior bone block procedure in posterior shoulder instability: a long-term follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 92(5):651–655

Millett PJ, Schoenahl JY, Register B, Gaskill TR, van Deurzen DF, Martetschläger F (2013) Reconstruction of posterior glenoid deficiency using distal tibial osteoarticular allograft. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 21(2):445–449

Petrera M, Veillette CJ, Taylor DW, Park SS, Theodoropoulos JS (2013) Use of fresh osteochondral glenoid allograft to treat posteroinferior bone loss in chronic posterior shoulder instability. Am J Orthop 42(2):78–82

Provencher MT, Frank RM, LeClere LE, Metzger PD, Ryu JJ, Bernhardson A, Romeo AA (2012) The Hill–Sachs lesion: diagnosis, classification, and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 20:242–252

Robinson CM, Seah M, Akhtar MA (2011) The epidemiology, risk of recurrence, and functional outcome after an acute traumatic posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 93:1605–1613

Savoie FH 3rd, Holt MS, Field LD, Ramsey JR (2008) Arthroscopic management of posterior instability: evolution of technique and results. Arthroscopy 24(4):389–396

Scheffer HJ, Quist JJ, van Noortb A, van Oostveen DPH (2012) Allograft reconstruction for reverse Hill–Sachs lesion in chronic locked posterior shoulder dislocation: a case report. J Med Cases 3(2):89–93

Schliemann B, Muder D, Gessmann J, Schildhauer TA, Seybold D (2011) Locked posterior shoulder dislocation: treatment options and clinical outcomes. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 131(8):1127–1134

Scholes C, Houghton ER, Lee M, Lustig S (2013) Meniscal translation during knee flexion: What do we really know? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. Apr 9 [Epub ahead of print]

Schwartz DG, Goebel S, Piper K, Kordasiewicz B, Boyle S, Lafosse L (2013) Arthroscopic posterior bone block augmentation in posterior shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 22(8):1092–1101

Servien E, Walch G, Cortes ZE, Edwards TB, O’Connor DP (2007) Posterior bone block procedure for posterior shoulder instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 15(9):1130–1136

Smith T, Goede F, Struck M, Wellmann M (2012) Arthroscopic posterior shoulder stabilization with an iliac bone graft and capsular repair: a novel technique. Arthrosc Tech 1(2):e181–e185

Wirth MA, Seltzer DG, Rockwood CA (1994) Recurrent posterior glenohumeral dislocation associated with increased retroversion of the glenoid. a case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res 308:98–101

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cerciello, S., Visonà, E., Morris, B.J. et al. Bone block procedures in posterior shoulder instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24, 604–611 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-015-3607-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-015-3607-7