Abstract

Traumatic posterior shoulder dislocations are often accompanied by an impression fracture on the anterior surface of the humeral head known as a “reverse Hill-Sachs lesion”. This bony defect can engage on the posterior glenoid rim and subsequently lead to recurrent instability and progressive joint destruction. We describe a new modified arthroscopic McLaughlin procedure, which allows for filling of the bony defect with the subscapularis tendon and subsequently prevents recurrence of posterior instability. This technique creates a double-mattress suture providing a large footprint for the subscapularis and a broader surface area to allow for effective tendon to bone healing. Furthermore, it obviates the need for detaching the subscapularis tendon and avoids the morbidity potentially associated with open procedures.

Level of evidence V.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Traumatic posterior shoulder dislocations can lead to impression fractures on the anterior surface of the humeral head. Depending on the size, this so-called reverse Hill-Sachs lesion can engage on the posterior rim of the glenoid during internal rotation of the arm, leading to mechanical symptoms, pain or re-dislocation of the shoulder. Surgical intervention is indicated for cases of recurrent posterior dislocation due to an engaging reverse Hill-Sachs lesion to not only stabilize the shoulder but also help avoid progressive joint destruction and early osteoarthritis. It has been shown that a posterior capsulolabral repair (i.e. posterior Bankart repair) does not effectively treat instability in cases with engaging reverse Hill-Sachs lesions [4, 6, 29]. There have been several different techniques described that address the bony pathology found in this types of cases. Current techniques for addressing the anterior humeral head defect can be subdivided into two groups—anatomical and non-anatomical reconstructions. The goal of the anatomical procedures is to restore the original shape of the humeral head with a variety of different bone grafting techniques [11, 18, 20]. By distinction, the goal of the non-anatomical techniques is to restore stability by filling the defect with the subscapularis tendon.

In 1952, McLaughlin [21] was the first to describe the subscapularis tenodesis using an open transposition of the subscapularis into the bony defect. Hawkins and Neer [13] modified the technique and recommended transferring the subscapularis and lesser tuberosity into the defect. Since then, several reports have described a number of variations in the technique, all showing reliable clinical results [7, 8, 10]. The purpose of this article is to describe an arthroscopic approach, the so-called “reverse remplissage” or “arthroscopic McLaughlin procedure” that can be used to tenodese the subscapularis tendon into the Hill-Sachs lesion. This all-arthroscopic procedure that avoids the morbidity of some of the open technique that predated it, allows one to address the posterior capsulolabral pathology and obviates the need to detach the subscapularis tendon or lesser tuberosity. This new technique uses a double-mattress suture, therefore providing a broader footprint with less tendon strangulation and has not been described for reverse remplissage yet.

Preoperative evaluation and indication

The complete synopsis of history, clinical examination and imaging enables the surgeon to understand and classify the type and severity of instability. Subsequently, treatment options, which include non-operative and operative approaches, can be discussed with the patient.

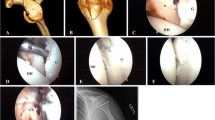

Radiographic evaluation includes a true anteroposterior, scapular Y and an axillary view. The three orthogonal views are essential to evaluate the bony contours of both the glenoid and the humerus and can help define any aberrant bony anatomy related to the dislocation events [9, 27]. When appropriate, 3-D imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is obtained to further evaluate potential soft tissue lesions and to better define the size and nature of bony injury (Fig. 1).

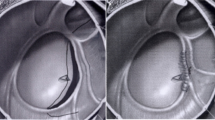

Axial plane of right shoulder MRI. Left: Preoperative status showing a large reverse Hill-Sachs lesion (white arrow) and slight posterior subluxation of the humeral head. Right: Postoperative status showing the subscapularis tendon scarred to the former Hill-Sachs lesion. The humeral head is well centred in the glenoid

Typically, the first line of treatment is non-operative with strengthening of the external rotators, particularly the infraspinatus [5]. Surgical treatment is indicated in symptomatic patients with recurrent dislocations after a failed conservative treatment, in those with active lifestyles who do not wish to risk the chance for re-dislocation, and those with sizeable bone defects.

Due to the rare occurrence of this pathology and the lack of evidence in literature, it remains unclear in which patients an arthroscopic McLaughlin procedure should be added to a standard posterior capsulolabral repair. The authors perform it as an adjunctive procedure in those patients who have symptomatic recurrent posterior glenohumeral instability that is associated with an anterior humeral head defect that involves <20 % of the size of the humeral head and that is <8 mm in depth. Larger humeral defects might be better treated with either disimpaction techniques in acute settings, with transfer of the lesser tuberosity, or by bone grafting [25].

Surgical technique

The beach chair position is utilized, and a pneumatic arm holder (Spider, Tenet Medical Engineering, Calgary, Canada) is used to assist with positioning of the surgical arm in space. The procedure can also be performed in the lateral decubitus position, but we believe it is easier to view the subdeltoid plane using the beach chair position as the anterior deltoid can be relaxed with forward flexion creating more working room. A standard posterior viewing portal is used, and two anterior portals are made under direct visualization. These include a standard anterior-superior portal and an anterior-inferior portal. It is useful to switch the camera to the anterior-superior portal during this process to carefully examine the posterior capsulolabral attachments and also to look at the size, depth and location of the bony injury of the anterior humeral head. With the camera in this position, a posterior drawer exam can confirm the direction of the instability and the degree of translation. Internal rotation of the arm can demonstrate the likelihood that the reverse Hill-Sachs lesion could engage the posterior glenoid.

After diagnostic arthroscopy is completed, we prefer to address any posterior capsulolabral derangement that is identified. This is done by placing the camera in the anterior-superior portal and establishing an accessory posterolateral portal. Bankart repairs, HAGL repairs and posterior capsule plications are utilized as needed. Next, the accessory posterior portal is closed with use of a #1 PDS suture. A switching stick is placed into the original posterior viewing portal and the camera can then safely be placed back in through the posterior portal without disrupting the posterior repair.

A 70-degree scope is now utilized to look over the front of the humeral head and carefully inspect the reverse Hill-Sachs lesion, subscapularis attachment and rotator interval. The rotator interval and subcoracoid space are debrided, and a plane is developed anterior to the subscapularis tendon to create a working space [19]. Great caution is exercised during this step to protect and avoid the axillary nerve at the inferior border of the subscapularis tendon. With the use of a rasp, the anterior bony defect is prepared and a bleeding bed of bone is created. Compacted articular cartilage is removed. An 8.25-mm cannula (Gemini, Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) is now placed into the anterior-inferior portal, and the leaflets are deployed to retract the fascia on the undersurface of the deltoid muscle belly and create a working space anterior to the subscapularis tendon. Through this anterior portal, two 3.0 mm suture anchors (BioComposite SutureTak, Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) are placed transtendinously through the subscapularis tendon and into the bony reverse Hill-Sachs defect (Fig. 2). Using standard suture shuttling methods (Lasso, Arthrex, Naples, Fl, USA), the four suture strands are brought through the subscapularis tendon and out the anterior-inferior portal in a mattress configuration (Fig. 3). These sutures are now tied in mattress stitches, thus filling the bony defect with the lateral aspect of the subscapularis tendon (Fig. 4). Dynamic arthroscopic exam can be utilized at this point to confirm that stability is restored and that the reverse Hill-Sachs defect no longer engages the glenoid rim. The entire procedure can be followed step-by-step in the attached video.

Discussion

The most important finding of the present study was that the presented arthroscopic McLaughlin procedure is a feasible adjunctive approach for difficult-to-treat posterior shoulder instability cases.

In comparison with anterior shoulder instability, posterior instability is less common. However, an anterior humeral head bone defect can contribute to recurrent dislocation and contribute to the creation of a chronic, recurrent posterior instability. McLaughlin [21] was the first to describe a treatment option for an impression fracture of the humeral head in chronic posterior shoulder instability cases. He recommended the transposition of the subscapularis tendon into the defect in order to avoid recurrent dislocations and early degenerative changes. This effectively rendered the impression defect unable to engage on the glenoid rim. Historically, various surgical approaches to address humeral bone loss have been described, including the anatomical bone grafting techniques [11, 18, 20] and the non-anatomical muscle/tendon transpositions [7, 8, 10, 13, 21] or rotational osteotomies [14].

Today, arthroscopic techniques have been developed for stabilization of posterior instability. These techniques are mainly analogous to anterior techniques and usually include a repair of the posterior Bankart lesion combined with a capsular shift [2, 3, 12, 15, 23, 28, 30, 32]. In cases without a posterior Bankart lesion, posterior capsulorrhaphy alone may suffice. Rarely a posterior HAGL may be encountered, and this too can be addressed arthroscopically [1]. Adjunctive anterior procedures such as a superior capsule shift or a rotator interval closure have been described to support restoration of posterior stability [22, 23, 26, 31, 33], although some recent biomechanical data suggest that this may not have much of an effect on posterior stability [24]. However, in cases of recurrent posterior dislocation associated with an engaging reverse Hill-Sachs lesion, the surgeon should be compelled to address the disruption of the bony anatomy. Therefore, the purpose of this article was to describe our modified technique of an arthroscopic McLaughlin procedure. Similar to the open technique described by Charalambous et al. [7] and an arthroscopic technique published by Krackhardt et al. [17], the subscapularis tendon is not detached but mobilized and tightened into the bony defect with suture anchors. Our technique differs from that of Krackhardt et al. [17] in that we place one suture anchor superior and one inferior into the defect. By doing so, a larger footprint is established which allows for a broader area of contact and an improved healing environment for the subscapularis tendon. Furthermore, we perform a double-mattress suture to avoid tissue necrosis related to suture strangulation, which has been described by Koo et al. [16] as a potential pitfall for the remplissage technique.

Our arthroscopic approach allows for improved visualization and avoidance of the surgical morbidity associated with open arthrotomy, such as detachment of the subscapularis tendon or osteotomy of the lesser tuberosity. The main limitation of the present study is related to the type of the article. As a technical note, it focuses on the description of a new technique and cannot provide any information about the clinical results of the procedure. Therefore, further clinical investigation will be necessary in order to prove the value of this technique. However, this manuscript can help orthopaedic surgeons who face clinical and surgical decisions about borderline posterior instability patients in daily clinical practice.

References

Ames JB, Millett PJ (2011) Combined posterior osseous Bankart lesion and posterior humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments: a case report and pathoanatomic subtyping of “floating” posterior inferior glenohumeral ligament lesions. J Bone Joint Surg Am 93(20):111–114

Antoniou J, Harryman DT 2nd (2000) Arthroscopic posterior capsular repair. Clin Sports Med 19(1):101–114

Bahk MS, Karzel RP, Snyder SJ (2010) Arthroscopic posterior stabilization and anterior capsular plication for recurrent posterior glenohumeral instability. Arthroscopy 26(9):1172–1180

Bigliani LU, Pollock RG, McIlveen SJ, Endrizzi DP, Flatow EL (1995) Shift of the posteroinferior aspect of the capsule for recurrent posterior glenohumeral instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am 77(7):1011–1020

Bottoni CR, Franks BR, Moore JH, DeBerardino TM, Taylor DC, Arciero RA (2005) Operative stabilization of posterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med 33(7):996–1002

Burkhart SS, De Beer JF (2000) Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic Bankart repairs: significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging Hill-Sachs lesion. Arthroscopy 16(7):677–694

Charalambous CP, Gullett TK, Ravenscroft MJ (2009) A modification of the McLaughlin procedure for persistent posterior shoulder instability: technical note. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 129(6):753–755

Checchia SL, Santos PD, Miyazaki AN (1998) Surgical treatment of acute and chronic posterior fracture-dislocation of the shoulder. J Should Elb Surg 7(1):53–65

Cicak N (2004) Posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br 86(3):324–332

Finkelstein JA, Waddell JP, O’Driscoll SW, Vincent G (1995) Acute posterior fracture dislocations of the shoulder treated with the Neer modification of the McLaughlin procedure. J Orthop Trauma 9(3):190–193

Gerber C, Lambert SM (1996) Allograft reconstruction of segmental defects of the humeral head for the treatment of chronic locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 78(3):376–382

Goubier JN, Iserin A, Duranthon LD, Vandenbussche E, Augereau B (2003) A 4-portal arthroscopic stabilization in posterior shoulder instability. J Should Elb Surg 12(4):337–341

Hawkins RJ, Neer CS 2nd, Pianta RM, Mendoza FX (1987) Locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 69(1):9–18

Keppler P, Holz U, Thielemann FW, Meinig R (1994) Locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder: treatment using rotational osteotomy of the humerus. J Orthop Trauma 8(4):286–292

Kim SH, Ha KI, Park JH, Kim YM, Lee YS, Lee JY, Yoo JC (2003) Arthroscopic posterior labral repair and capsular shift for traumatic unidirectional recurrent posterior subluxation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 85-A(8):1479–1487

Koo SS, Burkhart SS, Ochoa E (2009) Arthroscopic double-pulley remplissage technique for engaging Hill-Sachs lesions in anterior shoulder instability repairs. Arthroscopy 25(11):1343–1348

Krackhardt T, Schewe B, Albrecht D, Weise K (2006) Arthroscopic fixation of the subscapularis tendon in the reverse Hill-Sachs lesion for traumatic unidirectional posterior dislocation of the shoulder. Arthroscopy 22 (2):227 e221–227 e226

Mankin HJ, Doppelt S, Tomford W (1983) Clinical experience with allograft implantation. The first ten years. Clin Orthop Relat Res 174:69–86

Martetschlager F, Rios D, Boykin RE, Giphart JE, de Waha A, Millett PJ (2012) Coracoid impingement: current concepts. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. doi:10.1007/s00167-012-2013-7

McDermott AG, Langer F, Pritzker KP, Gross AE (1985) Fresh small-fragment osteochondral allografts. Long-term follow-up study on first 100 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res 197:96–102

Hl McLaughlin (1952) Posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 24–A(3):584–590

Millett PJ, Clavert P, Hatch GF 3rd, Warner JJ (2006) Recurrent posterior shoulder instability. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 14(8):464–476

Millett PJ, Clavert P, Warner JJ (2003) Arthroscopic management of anterior, posterior, and multidirectional shoulder instability: pearls and pitfalls. Arthroscopy 19(Suppl 1):86–93

Mologne TS, Zhao K, Hongo M, Romeo AA, An KN, Provencher MT (2008) The addition of rotator interval closure after arthroscopic repair of either anterior or posterior shoulder instability: effect on glenohumeral translation and range of motion. Am J Sports Med 36(6):1123–1131

Ponce BA, Millett PJ, Warner JP (2004) Management of posterior glenohumeral instability with large humeral head defects. Tech Should Elb Surg 5(3):146–156

Provencher MT, Mologne TS, Hongo M, Zhao K, Tasto JP, An KN (2007) Arthroscopic versus open rotator interval closure: biomechanical evaluation of stability and motion. Arthroscopy 23(6):583–592

Robinson CM, Aderinto J (2005) Recurrent posterior shoulder instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87(4):883–892

Savoie FH 3rd, Holt MS, Field LD, Ramsey JR (2008) Arthroscopic management of posterior instability: evolution of technique and results. Arthroscopy 24(4):389–396

Steinmann SP (2003) Posterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 19:102–105

Williams RJ 3rd, Strickland S, Cohen M, Altchek DW, Warren RF (2003) Arthroscopic repair for traumatic posterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med 31(2):203–209

Wirth MA, Groh GI, Rockwood CA Jr (1998) Capsulorrhaphy through an anterior approach for the treatment of atraumatic posterior glenohumeral instability with multidirectional laxity of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 80(11):1570–1578

Wolf EM, Eakin CL (1998) Arthroscopic capsular plication for posterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 14(2):153–163

Yamamoto N, Itoi E, Tuoheti Y, Seki N, Abe H, Minagawa H, Shimada Y, Okada K (2006) Effect of rotator interval closure on glenohumeral stability and motion: a cadaveric study. J Should Elb Surg 15(6):750–758

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (MP4 75,023 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martetschläger, F., Padalecki, J.R. & Millett, P.J. Modified arthroscopic McLaughlin procedure for treatment of posterior instability of the shoulder with an associated reverse Hill-Sachs lesion. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 21, 1642–1646 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-012-2237-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-012-2237-6