Abstract

Objectives

Ethnic inequalities in health (EIH) are unjust public health problem that emerge across societies. In Israel, despite uniform healthcare coverage, marked EIH persist between Arabs and Jews.

Methods

We draw on the ecosocial approach to examine the relative contributions of individual socioeconomic status (SES), psychosocial and health behavioral factors, and the living environment (neighborhood problems, social capital, and social participation) to explaining ethnic differences in self-rated health (SRH). Data were derived from two nationwide studies conducted in 2004–2005 of stratified samples of Arabs (N = 902) and Jews (N = 1087).

Results

Poor SRH was significantly higher among Arabs after adjustment for age and gender [odds ratio and 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.94 (1.57–2.40)]. This association was reversed following adjustment for all possible mediators: OR (95% CI) = 0.70(0.53–0.92). The relative contribution of SES and the living environment was sizable, each attenuating the EIH by 40%, psychosocial factors by 25%, and health behaviors by 16%.

Conclusions

Arabs in Israel have poorer SRH than Jews. Polices to reduce this inequality should mainly focus on improving the SES and the living conditions of the Arabs, which might enhance health behaviors and well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ethnic inequalities in health (EIH) represent a persistent, complex public health problem in many countries (Nielsen and Krasnik 2010). Racial or ethnic minority status is related to higher morbidity and mortality compared with majority groups (Bombak and Bruce 2012; Dinesen et al. 2011; Krieger et al. 2011; Williams and Collins 2001). From human rights perspective, EIH are unjust and it violates the basic right to health and should be eliminated (Braveman 2014). While countries strive to tackle EIH, policies have not always focused on improving minorities’ health (Lorant and Bhopal 2011). Partly, this was due to earlier assumptions about what explains EIH—assumptions that pathologized ethnic minorities, stigmatized them by labelling them as sick, or blamed them for transmitting diseases (Nazroo 2003). Research in social epidemiology has shifted this discourse to focus on the social, economic, and political determinants of minorities’ health. Acknowledging the role of social and economic policies in shaping these determinants of health among minorities this encouraged the emergence of different approaches to studying EIH. Material approaches assume that socioeconomic status (SES) has a major role, as ethnic minority groups are often concentrated in low socioeconomic areas and live in poverty. Both institutional discriminations at the policy level and interpersonal discrimination limit the educational and work opportunities among minorities, which relegate them to poverty (Krieger et al. 2011). Psychosocial approaches assert that absolute income is not sufficient to fully explain health inequalities, and draw on a relative income approach; that is, considering income inequality and one’s own income relative to others can elevate stress, while material resources and social support might be limited (Wilkinson and Pickett 2010). Based on this approach, higher exposure to stress and higher vulnerability among minorities adversely affect health (Krieger et al. 2011), both through biological, neuro-psychological mechanisms, and indirectly through risky behaviors such as smoking (Mindell et al. 2014). Other approaches relate to the social and structural living environment, emphasizing the role of neighborhood SES, community social cohesion (Daoud et al. 2016), and social capital (Daoud et al. 2017; Kawachi et al. 1999) in explaining health inequalities, although the role of social capital remains controversial (Uphoff et al. 2013).

The “ecosocial” approach (Krieger 1999) attempts to integrate insights from multiple perspectives on EIH while emphasizing contextual root causes of the ethnic and racial inequalities in health. EIH are complex, socially constructed, and embedded in the historical, political, and social determinants of health in a specific country context (Krieger 1999). Discriminatory policies situate minorities low in the social hierarchy (Krieger et al. 2011), creating deprived social and structural living environments that determine poor health (Williams and Collins 2001). Minorities in different countries experience these underlying causes at different levels, depending on their specific context (Krieger 1999). Thus, understanding country-specific EIH requires clarifying the mechanisms of inequality as they function in that context. Most research on the pathways to EIH has been conducted in North America and Europe (Moubarac 2013); less is known about these pathways in other societies.

In Israel, the historical—socio-political context and the ethno-cultural composition of Jewish majority and Arab minority, and the long-lasting Palestinian–Israeli conflict make Israel a setting of interest to study EIH. While in many countries, minorities comprise mostly new immigrants, Arab citizens of Israel are native-born people who became a minority after the establishment of the state in 1948 (Ghanem 2002). This makes their profile unique compared with immigrant ethnic minorities, but similar to the context of indigenous populations, and their case can be examined without confounding by immigration. Arabs were under military administration for about 18 years after the establishment of the state of Israel, which had large tremendous effects on the economic development of this population (Lewin-Epstien and Semyonov 1994) and hindered political and social integration (Ghanem 2002). This fostered economic and social enclaving, which helped them to survive, but also limited their financial prospects in the long term (Lewin-Epstien and Semyonov 1994). With few exceptions, Arabs and Jews are also enrolled in separate public education systems, with Arab schools suffering from discrimination in budgets and resources (Abu-saad 2004). In addition, land confiscations and changing social class among Arabs have been accompanied by social and lifestyle transitions that may have affected their health (Daoud et al. 2009b). Arabs now comprise 20.8% of the population (Central Bureau of Statistics 2016), but have lower SES compared with their Jewish counterparts: lower education (Abu-saad 2004), higher unemployment rates or employment in unskilled or low skilled professions, low-income level (about 34% below the national average), and high poverty rates (54% compared with 19% of all families in Israel) (Institution for Social Security 2015). There are also huge gaps in living conditions between the groups, as Arab neighborhoods are characterized by high poverty and neighborhood problems, including crime, violence, and road safety issues the inter alia related to reduced social cohesion and social capital (Daoud et al. 2017; Obeid et al. 2014).

The Jewish majority currently comprises 75% of the population, Israeli-born individuals, mostly descendants of immigrants, or immigrants. During the first two decades after its establishment, Israel absorbed close to one million Jewish immigrants, and many of them refugees from Europe and Arab countries (Shuval and Anson 2000). The state invested many resources in employment, housing, and health for them (Shuval and Anson 2000). Over the years, fundamental transitions have taken place in the social and economic structures of Israel. It has been noted that Israel’s economy developed rapidly, mainly due to advances in industry and technology, and mainly in the Jewish sector, suggesting elevating its standard of living (Shuval and Anson 2000).

The 1995 National Health Insurance Law aimed to reduce health inequalities among all Israeli citizens through universal health coverage was enacted. Every resident is now entitled to a uniform basic basket of services. Yet, because some require co-payment and other services or therapies are available only via supplemental insurance or privately, Arabs face more obstacles in accessing health care services (Filc 2010). The health inequalities persist between the Arab and Jewish populations (Israel Center for Disease Control 2011). While life expectancy in the past two decades increased substantially among all Israeli groups, Arabs have lower life expectancy. The incidence of several chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes) has increased in recent years among Arabs more than among Jews (Israel Center for Disease Control 2011). Arabs have also reported poorer self-rated health (SRH) than Jews (Baron-Epel et al. 2005). However, less is known about the factors that explain EIH in Israel.

Conceptual framework

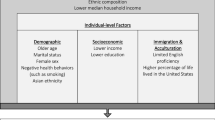

Drawing on the ecosocial approach (Krieger 1999), we aimed to examine a combination of individual factors, as well as social and structural aspects of the living environment as a means of explaining EIH between Arabs and Jews in Israel.

Our conceptual framework (Fig. 1) includes individual factors: material circumstances, represented by two SES measures (education and income); psychosocial factors reflecting higher stress (Krieger et al. 2011) and lower social support (Osman et al. 2017); and poorer health behaviors (Mindell et al. 2014). The social and structural conditions of the living environment were assessed by social capital (Daoud et al. 2017; Kawachi et al. 1999), social participation (Lindstrom et al. 2002), and neighborhood problems (Steptoe and Feldman 2001) that were adapted to the Israeli context and included questions about crime and violence and safety problems. Neighborhood variables were contextual and measured by direct questions and not aggregated data, and have been used in the previous research in Israel (Baron-Epel et al. 2005; Daoud et al. 2009b; Obeid et al. 2014; Soskolne and Manor 2010).

Methods

Data

Data were obtained from two nationally representative samples of Jewish (Soskolne and Manor 2010) and Arab (Daoud et al. 2009a) populations in Israel. In each study, one adult aged 30–70 was selected from each sampled household, with a male and a female selected at alternate households. A similar sampling strategy and a core questionnaire were used in both studies, which were conducted in 2004–2005. Jewish participants were interviewed in Hebrew or Russian [for immigrants from the former Soviet Union (FSU)]. The response rate was 68% (Soskolne and Manor 2010). For the current analysis, we excluded Jewish immigrants arriving after 1990 from FSU, because they differ culturally from the “veteran” Jewish population, and their health status in the first decade after immigration was poorer, largely due to conditions in their countries of origin (Shuval and Anson 2000). The Jewish sample, therefore, included only Israeli born or veteran immigrants (N = 1104). Interviews with Arabs were conducted in Arabic, reaching a response rate of 78%, with a total of 902 participants (Daoud et al. 2009a).

Both surveys were conducted within the “1948 borders” of Israel and included only localities of 5000 residents or more. The surveys are representative of the respective Jewish or Arab populations in Israel by gender, age, and education, except those living in small villages. More details are available elsewhere (Daoud et al. 2009b; Soskolne and Manor 2010). Both studies were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Centre, Jerusalem.

Study measures

Self-rated health (SRH) The dependent variable of SRH, an important measure of health that is predictive of mortality in different communities (Idler and Benyamini 1997), including the Arab and Jewish populations in Israel (Baron-Epel et al. 2005), was measured using the question: “How do you rate your health in general?” (Idler and Benyamini 1997). Answer categories were dichotomized into Good (“Excellent”/“Very good”) and Poor (“Fair”/“bad”/“Very bad”), as has been done in many studies (Idler and Benyamini 1997; Manor et al. 2001; Nielsen and Krasnik 2010).

Ethnicity this primary independent variable was determined by the participant’s self-reported ethnic identity.

Demographic control variables were gender and age (a continuous variable).

Groups of potential explanatory variables The study included two groups of individual factors and social and structural factors of the living environment, presented in Appendix 1 in supplementary material.

Data analysis

There are numerous ways of measuring social inequalities in health. We focused on evaluating the odds of poor SRH among the two ethnic groups. Our analytical approach involved examining the relative contribution of potential mediators in the association between ethnicity and SRH. These variables were grouped into the following: individual factors, including SES; psychosocial factors; health behaviors; and the social and structural living environment (social capital, social participation, and neighborhood problems), which were measured by direct questions and not aggregated data and present the participant’s perceptions of the neighborhoods. The analysis was conducted in stages. First, we compared Arab and Jewish participants, examining associations between ethnicity, SRH, and the explanatory variables. Then, we examined potential interactions between ethnicity, SRH, and age, and then between ethnicity, SRH, and gender. We found no significant interactions. Our analysis was, therefore, based on the overall study sample, namely, both genders and all age groups.

We focused on variables significantly associated (P < 0.05) with ethnicity and/or SRH. We checked potential collinearity between these variables; none were correlated above our pre-specified threshold of 0.6. The three social capital variables (‘fairness’, ‘mutual help’, and ‘trust’) and ‘smoking’ were not associated with SRH or ethnicity and were excluded from the multivariate logistic regression modelling.

Our strategy of analysis for exploring potential mediators of the association between ethnicity and SRH has been used in the previous studies on pathways to explaining inequalities in health (Skalicka et al. 2009; van Oort et al. 2005). We conducted different logistic regression models in the multivariate analysis. Initially, we examined “minimally adjusted odds ratio” for ethnic differences in poor SRH (Model 1), adjusted only for age and gender. Subsequent models included groups of explanatory variables: SES (Model 2), psychosocial factors (Model 3), health behaviors (Model 4), and the social and structural environment (Model 5). The final model included all variables (Model 6). Each model was adjusted for age and gender. The reference group for ethnicity was Jews. The relative contribution (%) of each of the groups of variables to explaining EIH was calculated based on differences in the odds ratio (OR) between the unadjusted model (Model 1) and each of the ORs in the following adjusted models. Analyses were conducted using SPSS v23.

Results

Poor SRH was higher among Arabs than Jews: 36.3% versus 28.9% (P ≤ 0.001). Arab participants had lower SES (education and income) compared with their Jewish counterparts (Table 2). We also found significant differences between Arab and Jewish participants for most of the study variables. Arab participants also had lower mean scores of social support and social participation, and higher chronic stress and stressful life events. Arabs were also less likely than Jews to report consuming a balanced diet or engaging in weekly physical activity, but did not differ in smoking behavior. Regarding the living environment, Arabs reported lower levels than Jews in two of the measures of social capital (‘trust’ and ‘mutual help’). Almost two-thirds of Arabs and only one-third of Jews reported severe or serious neighborhood problems (Table 1).

Table 2 presents the associations between the study variables and SRH. Poor SRH was higher among: women; participants with lower SES; and those with lower social participation or social support levels, higher chronic stress, and neighborhood problems. Poor SRH was also higher among participants who reported less physical activity and those who reported a less balanced diet.

The relative contribution of groups of explanatory variables to the association between ethnicity and SRH is shown in Table 3. In Model 1, Arabs reported almost double the odds of poor SRH compared with Jews [Odds Ratio (OR) 1.94 and 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.57, 2.40]. This OR was reduced in Models 2 through 6. Adjustment for SES (model 2) reduced the OR by 41% compared with Model 1, making the association non-significant (OR = 1.15, 95% CI = 0.91, 1.46). Psychosocial factors reduced the OR by 25%, but the association remained significant (Model 3 OR = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.14, 1.82). The effect of health behaviors was smaller: a reduction of 16% in the OR of Model 4 (OR = 1.63, 95% CI = 1.31, 2.03). A large attenuation of 42% occurred in Model 5 following adjustment for the social and structural environment variables of social participation and neighborhood problems (OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 0.88, 1.43). In Model 6, after inclusion of all the variables, the association between ethnicity and SRH was reversed and was statistically significant (OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.53, 0.92).

Discussion

This study found poorer SRH in the Arab minority compared with the Jewish majority in Israel. This inequality is consistent with results from studies on minorities in other countries: the UK (Mindell et al. 2014), USA (Krieger et al. 2011), European countries (Nielsen and Krasnik 2010), and Canada, Australia, and New Zealand (Bombak and Bruce 2012), and confirms consistent findings of the previous studies in Israel (Baron-Epel et al. 2005; Daoud et al. 2009a). Our study is the first we know of Israel that integrates individual factors with living-environment factors that we considered underpin EIH. Our work revealed that the gap is completely attenuated, and even reversed, after adjustment for all of these explanatory variables. The relative contribution of SES and social and structural living environments was sizable: each attenuated the association between ethnicity and SRH by about 40%. The important contribution of SES to explaining EIH supports findings from different countries—for example, in England (Mindell et al. 2014)—as well as between native-born and immigrant citizens of Belgium (Lorant and Bhopal 2011) and Sweden (Lindstrom et al. 2002). This might be explained by high concentration of ethnic minorities in lower social classes (Chandola 2001), similar to the situation in Israel. Our result that SES explains Jewish–Arab inequality might reflect long-term discriminatory policies in education (Abu-saad 2004) and work opportunities that have led to widening income inequality between Arabs and Jews. Others showed that discrimination is related to Arabs’ health behaviors (Osman et al. 2017). While some assume that Arabs have gained protection from an ethnic enclave economy (Lewin-Epstien and Semyonov 1994), and despite some attempts to provide employment opportunities for the Arabs, our first recommendation for policy initiatives would be to invest in their education system (as Arabs have a separate public schools system) in vocational and professional training, and create better work opportunities to increase income as a means of reducing EIH.

The social and structural living environments had a similar impact as SES in explaining EIH. Of the social factors, only social participation was associated with both SRH and ethnicity in our study. This might suggest that increased social participation among Arabs might reduce EIH. Social participation had been an important factor in explaining inequalities in SRH in different countries (Lindstrom et al. 2002), and was associated with improved SRH in the previous studies in Israel (Daoud et al. 2009a; Soskolne and Manor 2010). It could be that those who are socially active are more likely to engage in activities that improve health and reduce stress (Lindstrom et al. 2002). On the other hand, since this is a cross-sectional study, we cannot determine if those who report good SRH are more likely or more able to participate.

In contrast, no association of the other measures of the social environment—that is, the three social capital measures (trust, mutual help, and fairness)—with SRH was found. These measures were not associated with SRH at the bivariate level and were, therefore, excluded from the multivariate models. While this finding echoes the conclusion of one literature review that showed inconsistent results regarding the role of social capital in explaining social inequalities in health (Uphoff et al. 2013), further studies are recommended.

The other environmental factor that contributed significantly to explaining the reduction in OR of EIH was neighborhood problems. Lack of investment in the infrastructure of Arab towns and villages (Daoud et al. 2017; Lewin et al. 2006) might underlie the higher proportion of Arabs reporting ‘severe problems’ in their neighborhoods. For historical reasons, 85% of Arabs live apart from the Jews; there are only eight mixed towns in Israel. Despite the health benefits of the ‘ethnic density effect’ (Becares et al. 2009), which suggests a protective effect for minorities living in concentrated areas, neighborhood segregation is fundamental to discrimination and a root cause of racial and socioeconomic inequalities in health (Daoud et al. 2016, 2017; Williams and Collins 2001). Likewise, ward economic deprivation in the UK has been associated with poorer health among Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and other minorities (Chandola 2001). Lower SES in Arab neighborhoods was associated with higher neighborhood problems, increased violence (Daoud et al. 2017), and lower safety (Obeid et al. 2014). Based on this, we believe that policies aiming to enhance living conditions in Arab neighborhoods reduce violence, and increase in safety could also lead to reductions in EIH.

In our study, the psychosocial factors of stress and social support contributed less than SES and the living environment to explaining EIH, but did attenuate the association. Chronic stress, such as that arising from work, family, and social difficulties, was higher among Arabs and may reflect the consequences of their lower SES. However, while political conflict is probably a source of chronic stress for both groups, each population may still be affected differently by historical stressors. These may include the political status of Arabs, their trauma due to displacement (Daoud et al. 2012) and systematic or institutional discrimination (Lewin et al. 2006; Osman et al. 2017), and rapid changes in lifestyle that have likely affected their health (Daoud et al. 2009a); Jews, meanwhile, faced the horror or legacy of the Holocaust, repeated wars, and major cultural and social transitions following immigration, whether as refugees or otherwise (Shuval and Anson 2000). However, our findings suggest that the better SRH reported by Jewish participants might have been protected by their higher SES, higher social support, and lower chronic stress in recent decades (Soskolne and Manor 2010). Other factors include greater availability of, and better access to, social and health care services (Filc 2010).

The marked ethnic differences in health behaviors we found in our study are similar to those found in nationwide surveys on smoking, obesity, and physical activity (Israel Center for Disease Control 2011). Yet, the health behaviors made little contribution to explaining EIH. It may be that in Israel, structural factors of SES and living environments are substantially more important than individual factors in causing ethnic inequalities in SRH. However, since other research has found marked gender differences in health behaviors within each of the ethnic groups (Israel Center for Disease Control 2011), these differences might have reduced the role of health behaviors in explaining the inequalities in SRH in our study. For example, while smoking is higher among Arab than Jewish men, it is much higher among Jewish than Arab women (Israel Center for Disease Control 2011). These differences would have minimized the effect of smoking in the current study. Since we did not stratify by gender, as we had a limited sample size, we suggest that future studies look specifically at the role of smoking in explaining EIH in Israel. The exclusion of smoking from the multivariate analysis in our study (due to the non-significant associations with ethnicity and SRH) might have affected our results. However, two previous studies in Israel found that the contribution of health behaviors to explaining social inequalities SRH within each of the ethnic groups (Arabs and Jews) was lower than the contribution of SES (Daoud et al. 2009a; Soskolne and Manor 2010). Furthermore, one study in England found that both SES and health behaviors are important explanatory variables for inequalities in SRH and chronic illness (Mindell et al. 2014). It might be that smoking is a more important mediator for explaining more ‘objective’ health outcomes, such as chronic disease. Although SRH has been associated with mortality and morbidity (Idler and Benyamini 1997), it is a more subjective health outcome (Daoud et al. 2009a).

Interestingly, in our final model, which included all factors, ethnic inequalities were reversed, suggesting that poor SRH was significantly higher among Jewish participants after adjustment for these various factors. While similar results have been found elsewhere (Mindell et al. 2014), this might indicate that the explanatory factors we studied fully explained EIH in SRH in Israel, and are likely to explain EIH in other health indicators, as SRH has been associated with mortality and morbidity in many studies (Idler and Benyamini 1997). This suggests that SRH of Arabs in Israel might be improved, or even surpass that of Jewish Israelis, if individual factors (SES, psychological factors, and health behaviors), as well as social and structural environments are improved. This might also suggest that removing these barriers (individual SES and social and structural environments) might reveal resilience in the Arab community in Israel.

Some limitation can be noted regarding our study. First, due to the cross-sectional design, we cannot determine causality for the associations between ethnicity and SRH. Another limitation relates to sample size. We found no significant interactions between ethnicity and either age or gender, indicating that ethnic inequalities in SRH exist across these groups and that there is no need to stratify our sample by age or gender groups. However, this might also indicate lack of power, as our sample might not be large enough to examine associations between ethnicity and SRH for different gender and age groups. Future research based on larger samples can examine the associations by age and gender groups. More research is also needed into social and structural environments, as our data on the neighborhoods were contextual and not aggregated. A main strength of this study is its reliance on a conceptual framework and the use of nationally representative samples of non-institutionalized, general populations.

Finally, ethnic inequalities are persistent public health problem in many countries, including Israel. Our findings that SES and social and structural environment mainly account for these ethnic inequalities in Israel suggest that policies seeking to raise educational achievement in the Arab minority and increase work opportunities for this group might decrease the income gap and gradually reduce this health gap. Improving the structural and social living environment in Arab neighborhoods is also a valuable policy objective, which might improve health behaviors and psychosocial factors, and could further reduce the unjust ethnic inequalities in SRH.

References

Abu-saad I (2004) Separate and unequal: the role of the state educational system in maintaining the subordination of Israel’s Palestinian arab citizens. Soc Identities 10:101–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350463042000191010

Baron-Epel O, Kaplan G, Haviv-Messika A, Tarabeia J, Green M, Kaluski D (2005) Self-reported health as a cultural health determinant in Arab and Jewish Israelis: MABAT–national health and nutrition survey 1999–2001. Soc Sci Med 61:1256–1266

Becares L, Nazroo J, Stafford M (2009) The buffering effects of ethnic density on experienced racism and health. Health Place 15:670–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.10.008

Bombak AE, Bruce SG (2012) Self-rated health and ethnicity: focus on indigenous populations. Int J Circumpolar Health. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v3471i3400.1853810.3402/ijch.v71i0.18538

Braveman P (2014) What is health equity: and how does a life-course approach take us further toward it? Matern Child Health J 18:366–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-13-1226-9

Central Bureau of Statistics (2016) Israel in figures. http://www.cbs.gov.il/www/publications/isr_in_n16e.pdf. Accessed 1 Mar 2017

Chandola T (2001) Ethnic and class differences in health in relation to British South Asians: using the new national statistics socio-economic classification. Soc Sci Med 52:1285–1296

Daoud N, Soskolne V, Manor O (2009a) Educational inequalities in self-rated health within the Arab minority in Israel: explanatory factors. Eur J Pub Health 19:477–483

Daoud N, Soskolne V, Manor O (2009b) Examining cultural, psychosocial, community and behavioral factors in relationship to socio-economic inequalities in limiting longstanding illness among the Arab minority in Israel. J Epidemiol Community Health 63:351–358

Daoud N, O’Campo P, Urquia ML, Heaman M (2012) Neighbourhood context and abuse among immigrant and non-immigrant women in Canada: findings from the maternity experiences survey. Int J Public Health 57:679–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0367-8

Daoud N, Haque N, Gao M, Nisenbaum R, Muntaner C, O’Campo P (2016) Neighborhood settings, types of social capital and depression among immigrants in Toronto. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 51:529–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1173-z

Daoud N, Sergienko R, O’Campo P, Shoham-Vardi I (2017) Disorganization theory neighborhood social capital, and ethnic inequalities in intimate partner violence between Arab and Jewish women citizens of Israel. J Urban Health 94:648–665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-017-0196-4

Dinesen C, Nielsen SS, Mortensen LH, Krasnik A (2011) Inequality in self-rated health among immigrants, their descendants and ethnic Danes: examining the role of socioeconomic position. Int J Public Health 56:503–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-011-0264-6

Filc D (2010) Circles of exclusion: obstacles in access to health care services in Israel. Int J Health Serv 40:699–717

Ghanem A (2002) The Palestinians in Israel: political orientation and Aspiration. Int J Intercult Relat 26:135–152

Idler E, Benyamini Y (1997) Self rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav 38:21–37

Institution for Social Security (2015) Poverty indicators and social inequalities: annual report for 2014. Institution for Social security, Jerusalem

Israel Center for Disease Control (2011) The Health status in Israel, 2010. Ministry of Health, Jerusalem

Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Glass R (1999) Social capital and self rated health: a contextual analysis. Am J Public Health 89:1187–1193

Krieger N (1999) Embodying inequalities: a review of concepts, measures and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. Int J Health Serv 29:295–352

Krieger N, Kosheleva A, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Koenen K (2011) Racial discrimination, psychological distress, and self-rated health among US-born and foreign-born Black Americans. Am J Public Health 101:1704–1713. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2011.300168

Lewin AC, Stier H, Caspi-Dror D (2006) The place of opportunity: community and individual determinants of poverty among Jews and Arabs in Israel. Res Soc Stratif Mobil 24:177–191

Lewin-Epstien N, Semyonov M (1994) Sheltered labor markets, public sector employment, and socio-economic returns to education of Arabs in Israel. Am J Sociol 100:622–651

Lindstrom M, Merlo J, Ostergren PO (2002) Individual and neighbourhood determinants of social participation and social capital: a multilevel analysis of the city of Malmo. Swed Soc Sci Med 54:1779–1791

Lorant V, Bhopal R (2011) Comparing policies to tackle ethnic inequalities in health: Belgium 1 Scotland 4. Eur J Public Health 21:235–240. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckq061

Manor O, Power C, Matthews S (2001) Self-rated health and limiting longstanding illness: inter-relationships with morbidity in early adulthood. Int J Epidemiol 30:600–607

Mindell JS, Knott CS, Ng Fat LS, Roth MA, Manor O, Soskolne V, Daoud N (2014) Explanatory factors for health inequalities across different ethnic and gender groups: data from a national survey in England. J Epidemiol Community Health 68:1133–1144. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-203927

Moubarac JC (2013) Persisting problems related to race and ethnicity in public health and epidemiology research. Rev Saude Publica 47:104–115

Nazroo J (2003) The structuring of ethnic inequalities in health: economic position, racial discrimination, and racism. Am J Public Health 93:277–284

Nielsen S, Krasnik A (2010) Poorer self-perceived health among migrants and ethnic minorities versus the majority population in Europe: a systematic review. Int J Public Health 55:357–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-010-0145-4

Obeid S, Gitelman V, Baron-Epel O (2014) The relationship between social capital and traffic law violations: Israeli Arabs as a case study. Accid Anal Prev 71:273–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2014.05.027

Osman A, Daoud N, Thrasher JF, Bell BA, Walsemann KM (2017) Ethnic discrimination and smoking-related outcomes among former and current Arab male smokers in Israel: The buffering effects of social support. J Immigr Minor Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0638-9

Shuval J, Anson O (2000) Social Structure and Health in Israel. The Hebrew University Magnes Press, Jerusaelm

Skalicka V, van Lenthe F, Bambra C, Krokstad S, Mackenbach J (2009) Material, psychosocial, behavioural and biomedical factors in the explanation of relative socio-economic inequalities in mortality: evidence from the HUNT study. Int J Epidemiol 38:1272–1284. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyp262

Soskolne V, Manor O (2010) Health inequalities in Israel: explanatory factors of socio-economic inequalities in self-rated health and limiting longstanding illness. Health Place 16:242–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.10.005

Steptoe A, Feldman PJ (2001) Neighborhood problems as sources of chronic stress: development of a measure of neighborhood problems, and associations with socioeconomic status and health. Ann Behav Med 23:177–185. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2303_5

Uphoff EP, Pickett KE, Cabieses B, Small N, Wright J (2013) A systematic review of the relationships between social capital and socioeconomic inequalities in health: a contribution to understanding the psychosocial pathway of health inequalities. Int J Equity Health 12:54. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-54

van Oort FVA, van Lenthe FJ, Mackenbach J (2005) Material, psychosocial, and behavioural factors in the explanation of educational inequalities in mortality in the Netherlands. J Epidemiol Community Health 59:214–220. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.016493

Wilkinson R, Pickett K (2010) The spirit level: why equity is better for everyone?. Penguin Books, London

Williams D, Collins C (2001) Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep 116:404–416

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants in the studies and the Sir Isaiah Berlin Travel Scholarship Fund for MAR. The original studies were funded by the Israel National Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research [Grants no. 2001/7, a/95/2003].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical statement

Compliance with ethical standards and guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki involving human subjects. Both studies were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Centre in Jerusalem.

Consent forms

Written informed consent forms were obtained from all participants in both studies.

Funding

The original studies were funded by the Israel National Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research [Grants No. 2001/7, a/95/2003].

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Daoud, N., Soskolne, V., Mindell, J.S. et al. Ethnic inequalities in health between Arabs and Jews in Israel: the relative contribution of individual-level factors and the living environment. Int J Public Health 63, 313–323 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-017-1065-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-017-1065-3