Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to quantify the global burden of osteoporotic fracture worldwide.

Methods

The incidence of hip fractures was identified by systematic review and the incidence of osteoporotic fractures was imputed from the incidence of hip fractures in different regions of the world. Excess mortality and disability weights used age- and sex-specific data from Sweden to calculate the Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) lost due to osteoporotic fracture.

Results

In the year 2000 there were an estimated 9.0 million osteoporotic fractures of which 1.6 million were at the hip, 1.7 million at the forearm and 1.4 million were clinical vertebral fractures. The greatest number of osteoporotic fractures occurred in Europe (34.8%). The total DALYs lost was 5.8 million of which 51% were accounted for by fractures that occurred in Europe and the Americas. World-wide, osteoporotic fractures accounted for 0.83% of the global burden of non-communicable disease and was 1.75% of the global burden in Europe. In Europe, osteoporotic fractures accounted for more DALYs lost than common cancers with the exception of lung cancer. For chronic musculo-skeletal disorders the DALYs lost in Europe due to osteoporosis (2.0 million) were less than for osteoarthrosis (3.1 million) but greater than for rheumatoid arthritis (1.0 million).

Conclusion

We conclude that osteoporotic fractures are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, particularly in the developed countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Several studies have quantified the global burden of osteoporosis as judged by the current and predicted number of hip fractures [1–3]. The most recent study also quantified the global morbidity arising from hip fractures. In this study there were an estimated 1.31 million new hip fractures in 1990, and the prevalence of patients with disability due to hip fracture was estimated at 4.48 million [3]. There were 1.75 million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) lost, representing 0.1% of the global burden of disease worldwide and 1.4% of the burden for women from the established market economies.

Attention has focussed on hip fracture morbidity because epidemiological information is more widely available for the hip than for other sites of osteoporotic fracture. However, fractures in other sites contribute significantly to the burden of osteoporosis, particularly in younger individuals in whom osteoporotic fractures at sites other than the hip are much more common. For example, it has been estimated that in Swedish women between 50 and 54 years old, such fractures account for six times the morbidity of that arising from hip fracture [4, 5]. The aim of the present study was to estimate the global burden of all osteoporotic fractures and to compare the burden with that for other noncommunicable diseases.

Methods

The approach used was to compute the DALYs as used by the World Bank and the World Health Organization [6, 7]. This integrates the disability and life-years lost due to osteoporotic fracture. Demographic estimates of population numbers and mortality were taken from the Global Burden of Disease 2000 project [8], and the information was applied to 17 subregions of the world. For the purpose of presentation, the subregions were collapsed to the seven major regions shown in Table 1.

Incidence of fracture

The incidence of hip fracture was computed for the world regions for men and women age 50 years or more in 5-year age intervals, when possible, from the year 1990 onwards [9]. Hip fracture rates were supplemented with recent data from Thailand [10] and Cameroon [11]. Country-specific data were used for the subregions as shown in Table 1. When more than one estimate was available for a subregion, a mean value was used. When no estimate was available for a subregion, we used data from other subregions within the same global burden of disease region. For example, no estimate was available for AFRO E, so the data from Cameroon (AFRO A) were used for the subregions.

Other fractures associated with osteoporosis (“osteoporotic fracture”) comprised fractures of the forearm, humerus, spine, pelvis, other femoral fractures, tibia and fibula (in women), ribs, clavicle, scapula, and sternum [5]. Because few systematic data are available, we assumed that the ratio of the incidence of hip to that of other osteoporotic fractures was similar to that observed in Sweden. For example, between the ages of 50 and 54 years, hip fractures accounted for 4.7% and 3.8% of all osteoporotic fractures in men and women, respectively. These figures rise progressively with age, so that between the ages of 80 and 85 years, hip fractures account for 25.9% and 35.6% of all osteoporotic fractures in men and women [5]. We assumed, therefore, that these ratios of incidence would apply elsewhere. The adequacy of this assumption is not known worldwide, but the available information suggests that the pattern of fractures is similar in the Western world and Australia despite differences in incidence [12–15]. Also, within the United States, the pattern appears to be similar amongst blacks and whites. For example, in white women age 65–79 years, the ratio of hip, distal forearm, and proximal humeral fractures is 43%, 38%, and 19%, respectively. For black women the ratio is 45%, 36%, and 18%, respectively [16].

Years of life lost

Mortality after hip fracture was computed from the excess mortality after hip fracture and compared with that of the general population in each region [8]. Excess mortality by age and gender used data from Sweden [17] and in the base case assumed, therefore, that in each region the age-specific relative risk of death after hip fracture compared with that of the local population was similar to that of Sweden. The excess mortality after hip fracture is, however, partly due to comorbidity. An analysis from the Swedish population suggested that approximately 25% of deaths associated with hip fracture were causally related to the hip fracture event itself [18], and this assumption was used for the base case. Excess mortality has also been documented for other osteoporotic fractures, including those of the spine and proximal humerus, although not for forearm fractures [19, 20]. For fractures other than hip fractures, we assumed that the excess mortality attributable to the fracture would be proportional to the disutility occasioned at each fracture site. Disutilities (the cumulative loss of quality of life) were taken from Kanis et al. [4]. For example, the disutility in women age 70–74 years from hip fracture is 1.202 and for spine, humerus, and forearm fractures is 0.790, 0.305, and 0.08, respectively. For the same age, the excess mortality due to hip fracture is estimated at 25/100,000 of the population. Thus, the estimated excess deaths for spine fracture at the same age would be 16/100,000, for humerus fractures would be 6/100,000, and for forearm fractures would be 0.5/100,000 of the population.

The years of life lost due to osteoporotic fractures was computed from the number of fractures and the premature mortality. The years of life lost were age-weighted for the purposes of computing DALYs. The weighting assigns a greater value to a year of young adult life than to a year in the life of a child or an elderly person [7]. For example, a life-year valued at 1.0 at the age of 55 years is valued at 0.8 at the age of 60 years and 0.7 at the age of 70 years. Methods are given in detail elsewhere that describe the construction of specific software models for the computations [7, 21]. The weighting was removed in a sensitivity analysis.

Nonfatal outcomes

Disability due to fractures was computed from estimates of quality of life-adjusted life-years (QALYs) lost using methods previously described [5]. The disability weight, expressed as a fraction, describes a range of disutility between death (=1) and perfect health (=0). The cumulative utility lost (disutility) was used to compute the average duration of disease” using methods previously described [3]. The prevalence” of osteoporotic fracture in the year 2000 was computed from the population size, the duration of disease,” and the incidence of fracture and mortality rates for individuals with and without osteoporotic fractures. The computation assumes that the fracture and death hazards do not change with time. The years of life lost due to disability was calculated from the cumulative disability in the year 2000 due to new nonfatal osteoporotic fractures, and that of survivors from osteoporotic fractures that occurred before the year 2000.

Disability-adjusted life-years

The DALY was computed from the sum of the years of disabled life in survivors and the life-years lost due to premature mortality, using a 3% discount [3, 7].

Results

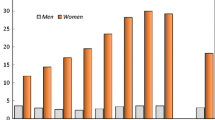

The estimated number of new osteoporotic fractures for the year 2000 was 9.0 million, of which 1.6 million were at the hip, 1.7 million were at the forearm, and 1.4 million were clinical vertebral fractures (Fig. 1, Table 2). Seventy percent of hip fractures occurred in women. The respective figures for forearm, spine, and humerus fractures were 80%, 58%, and 75% in women. Fractures at other sites were more common in men than in women. Overall, 61% of osteoporotic fractures occurred in women, so the female-to-male ratio was 1.6.

The peak number of hip fractures occurred between the ages of 75 and 79 years in both men and women, but for all fractures, the peak number occurred between 50 and 59 years and decreased with age (Table 3).

The greatest number of fractures was in Europe, followed by the Western Pacific region, southeast Asia, and the Americas. Collectively, these regions accounted for 96% of all fractures (Table 4). The Americas and Europe accounted for 51% of the burden worldwide.

The prevalence of fracture, defined as the number of individuals suffering disability, is shown by region in Table 5. Fracture sufferers were estimated at 56 million worldwide, with a female-to-male ratio of 1.6. As expected from the pattern of incidence, the prevalence was greatest in Europe.

The total DALYs lost was 5.8 million (Table 6). Of these, 51% were accounted for by fractures that occurred in Europe and the Americas. The burden was greater in women than in men, and the former accounted for 64% of DALYs. Hip fractures accounted for 0.82 million DALYs in men and 1.53 million DALYs in women, accounting for 41% of the global burden of osteoporosis.

The total DALYs were computed in the base case, in which years of life lost was weighted less in the elderly. When each year of life was valued at 1, the burden of DALYs increased from 5.8 million to 9.2 million (Table 7). As expected, changing assumptions concerning the excess mortality after hip fracture had a large impact on DALYs. When all deaths associated with hip fracture were assumed to be causally related, the numbers of DALYs lost doubled from 5.8 million to 11.3 million and increased still further to 18.8 million when the age weighting was removed.

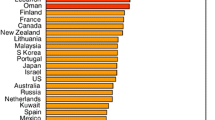

The total burden of osteoporosis accounted for 0.83% of the global burden of noncommunicable diseases, though this varied markedly by region (Fig. 2). Figures 3 and 4 show the burden in Europe compared with that for other chronic diseases. Osteoporosis accounted for more DALYs lost than rheumatoid arthritis did, but less than for osteoarthritis. With regard to neoplastic disorders, the burden of osteoporosis was greater than for all sites of cancer, with the exception of lung cancers.

Discussion

This study is a first attempt to estimate the global burden of osteoporotic fractures in terms of their incidence, prevalence of disabled individuals, excess mortality, and DALYs. For the year 2000 we estimated approximately 9 million new osteoporotic fractures, of which 1.6 million were fractures at the hip, 1.7 million were fractures at the forearm, and 1.4 million were clinical vertebral fractures. Because some fractures incur disability for a period much longer than 1 year after the event, the number of individuals suffering the consequences of fracture is much larger than the annual incidence. Under the assumptions used for this study, this number was estimated at approximately 50 million worldwide. The annual number of hip fractures estimated in this study in the year 2000 compares with a previously published estimate for the year 1990 of 1.3 million hip fractures worldwide, representing an increase of approximately 25% [3]. The earlier estimate is somewhat lower than others for 1990 [1, 2], but the differences are relatively small and may be accounted for by the improved database on which to estimate hip fracture in different regions of the world. The present study also emphasises the importance of fractures other than hip fracture in contributing to the numbers of fractures. Indeed, hip fracture accounted for 18.2% of the total number of osteoporotic fractures. Because of the severe consequences of hip fracture in particular, a larger burden (40%) of the DALYs lost were accounted for by hip fracture. However, the majority of the global burden of osteoporosis is accounted for by fractures other than those at the hip (60%).

An attractive feature of the approach used is that it permits comparisons across diseases. Overall, osteoporotic fractures accounted for 0.83% of the worldwide disability associated with noncommunicable diseases. For Europe, the proportion of noncommunicable diseases accounted for by osteoporosis was 1.75% of the total DALYs, and it outranked several other chronic diseases well established as burdensome to society, including rheumatoid arthritis and hypertensive heart disease. Our estimate suggests that osteoporotic fractures account for about two-thirds of the disability associated with osteoarthritis in Europe. Osteoporosis in Europe also contributed to a higher burden than the common neoplastic disorders, save only for lung cancer.

The present study is based on a large number of assumptions discussed previously [3, 22]. These include uncertainties about hip fracture rates in many subregions of the world. This deficit is, however, greatest for those regions of the world where hip fracture rates are assumed to be low, and more complete information is available for high risk countries in the developed world. Also, data are lacking on the mortality due to fracture worldwide. In this study we assumed that the excess mortality was similar to that in Sweden. This may be a reasonable assumption for the developed countries, but in the underdeveloped countries it is possible that a lower standard of healthcare would result in much greater disability than we have estimated. Our estimates may, therefore, be somewhat conservative, but again, any additional morbidity in these countries has a relatively modest impact on the global burden because of the much lower number of osteoporotic fractures. The data on disability associated with osteoporotic fractures are also largely drawn from Sweden. Although similar estimates are available from the UK, particularly for hip fracture [23], almost no data are available for the international variation in disutility associated not only with hip fracture but also for the many other types of osteoporotic fracture. Because of the uncertainties of disutility values several years after major fractures such as hip and pelvic fractures, we discounted utilities from the second year by 10% per year, and this high discount might also underestimate the long-term disability. All of these limitations point to the need for more epidemiological information on fracture rates and their implications worldwide.

Over and above these limitations, the age- and gender-adjusted burden of osteoporotic fractures other than hip fracture has been imputed from the ratio of hip fracture to other osteoporotic fractures using a Swedish database. For long bone fractures, this assumption seems to be reasonable, at least in the Western world (see Methods), but it may not hold true for vertebral fractures [24, 25]. There is a high correlation between hip fracture rates and admission to hospital for vertebral fracture such that vertebral fracture discharges are high in those regions where the incidence of hip fracture is also high [26, 27]. By contrast, prospective studies of the incidence of morphometric vertebral fractures have shown much less heterogeneity in vertebral fracture risk around the world [24, 25, 27]. If the disability associated with these fractures was shown to be similar worldwide, this would have a marked impact on increasing the disability associated with all osteoporotic fractures.

Most of these assumptions are conservative. With these caveats, the present data suggest that osteoporotic fractures comprise a very significant disease burden to society, particularly in the developed countries.

References

Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ III (1992) Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporos Int 2:285–289

Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA (1997) World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 7:407–413

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2004) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence, mortality and disability associated with hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 15:897–902

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Borgstrom F, Zethraeus N, De Laet C, Jonsson H (2004) Risk and burden of vertebral fractures in Sweden. Osteoporos Int 15a:20–26

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, Jonsson B, De Laet C, Dawson A (2000) The burden of osteoporotic fractures: a method for setting intervention thresholds. Osteoporos Int 12:417–427

World Health Organization (2004) The world health report: changing history. World Health Organization, Geneva

Murray CJL, Lopez AP (1996a) Global and regional descriptive epidemiology of disability. Incidence, prevalence, health expectancies and years lived with disability. In: Murray CJL, Lopez AD (eds) The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 201–246

World Health Organization (2002) World health report: reducing risk, promoting healthy life. World Health Organization, Geneva

Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Oden A, Oglesby AK (2002) International variations in hip fracture probabilities; implications for risk assessment. J Bone Miner Res 17:1237–1244

Lau EM, Lee JK, Suriwongpaisal P, Saw SM, Das De S, Khir A, Sambrook P (2001) The incidence of hip fracture in four Asian countries: the Asian Osteoporosis Study (AOS). Osteoporos Int 12:239–243

Zebaze RM, Seeman E (2003) Epidemiology of hip and wrist fractures in Cameroon, Africa. Osteoporos Int 14:301–305

Melton LJ III, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM (1999) Fracture incidence in Olmsted County, Minnesota: comparison of urban and with rural rates and changes in urban rates over time. Osteoporos Int 9:29–37

Singer BR, McLauchlan CJ, Robinson CM, Christie J (1998) Epidemiology of fracture in 1000 adults. The influence of age and gender. J Bone Joint Surg 80B:234–238

Sanders KM, Nicholson GC, Ugoni AM, Pasco JA, Seeman E, Kotowicz MA (1999) Health burden of hip and other fractures in Australia beyond 2000. Projections based on the Geelong Osteoporosis Study. Med J Aust 170:467–470

Lippuner K, von Overbeck J, Perrelet R, Bossard H, Jaeger P (1997) Incidence and direct medical costs of hospitalizations due to osteoporotic fractures in Sweden. Osteoporosis International 7:414–425

Arneson TJ, Melton LJ III, Lewallen DG, O’Fallon WM (1998) Epidemiology of diaphyseal and distal femoral fractures in Rochester, Minnesota, 1965–1984. Clinical Orthopaedics 234:188–194

Oden A, Dawson A, Dere W, Johnell O, Jonsson B, Kanis JA (1998) Lifetime risk of hip fractures is underestimated. Osteoporos Int 8:599–603

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O et al (2003) The components of excess mortality after hip fracture. Bone 32:468–473

Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, Sernbo I, Redlund-Johnell I, Patterson C, De Laet C, Jonsson B (2004) Mortality after osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 15:38–42

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B (2004b) Excess mortality after hospitalisation for vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int 15:108–112

World Health Organization (2002b) Global burden of disease. Discussion paper no. 54. WHO Statistical Information System http://www.who.int/whosis/burden/gbd2000docs

Williams A (1999) Calculating the global burden of disease. Time for a strategic reappraisal. Health Econ 8:1–8

Brazier J, Green C, Kanis JA (2002) On behalf of the Committee of Scientific Advisors, International Osteoporosis Foundation. A systematic review of health-state utility values for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 13:768–776

Cummings SR, Melton LJ (2002) Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 359:1761–1767

Felsenberg D, Silman AJ, Lunt M, Ambrecht G, Ismail AA, Finn JD, Cockerill WC, Banzer D, Benevolenskaya LI, Bhalla A, Bruges Armas J, Cannata JB, Cooper C, Dequeker J, Eastell R, Ershova O, Felsch B, Gowin W, Havelka S, Hoszowski K, Jajic I, Janot J, Johnell O, Kanis JA, Kragl G, Lopez Vaz A, Lorenc R, Lyritis G, Masaryk P, Matthis C, Miazgowski T, Parisi G, Pols HAP, Poor G, Raspe HH, Reid DM, Reisinger W, Scheidt-Nave C, Stepan J, Todd C, Weber K, Woolf AD, Reeve J, O’Neill TW (2002) Incidence of vertebral fracture in Europe: results from the European Prospective Osteoporosis Study Epos. J Bone Min Res 17:716-724

Johnell O, Gullberg B, Kanis JA (1977) The hospital burden of vertebral fracture in Europe: a study of national register sources. Osteoporos Int 7:138–144

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2005) Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 16(suppl 2):S3–S7

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Colin Mathers, World Health Organization, Geneva, who helped us with the DISMOD 2 computer programme and reviewed the manuscript. This project was supported by the International Osteoporosis Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Johnell, O., Kanis, J.A. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 17, 1726–1733 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4