Abstract

Background

Organophosphates and Pyrethroids are the most widely used pesticides worldwide and are known to have significant toxicity on the nervous system of the target pest. Assessment for combined toxicity of Organophosphate and Pyrethroid on Sf9 (Spodoptera frugiperda) cells is less explored. The present study demonstrates and compares the two organochemicals whose trade names are Ammo and Profex, for its cytotoxic potential on the insect Sf9 cells. Ammo and Profex were selected as the test chemicals as toxicity of these insecticides at molecular and cellular level is poorly understood.

Results

The results of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide assay demonstrated that Ammo and Profex exhibited significant cytotoxicity to Sf9 cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner. In our study, the IC50 value was obtained by MTT assay and the sub-lethal concentrations (IC50/20-17.5 µg/ml, IC50/10-35 µg/ml, and IC50/5–70 µg/ml for Ammo and IC50/20-20 µg/ml, IC50/10-40 µg/ml, and IC50/5-80 µg/ml for Profex) were selected for further tests. Acridine orange/ethidium bromide staining proved the apoptotic cell death on exposure of both the insecticides confirming its toxic potential. Furthermore, antioxidant status was assessed using DCF-DA staining and both the insecticides resulted into an increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. A dose- and time-dependent significant (p < 0.05) alterations in lipid peroxidase (LPO), glutathione (GSH) and catalase (CAT) activity were observed.

Conclusion

The results showed that both Ammo and Profex triggered apoptosis in Sf9 cells through an intrinsic mitochondrial pathway via the generation of ROS. Of the two insecticides, Ammo was found to be more toxic compared to Profex. The present study is important to evaluate the environmental safety and risk factors of Organochemicals’ exposure to crops and livestock.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Organophosphate (OP) insecticides are among the most common class of pesticides that are mainly used to control the insect pest populations. They are the group of insecticides whose key target is to inhibit Acetylcholine esterase (AChE) which is responsible for hydrolysis of Acetylcholine. The OPs phosphorylate the hydroxyl group of a serine residue on AChE in the central nervous system. It has been reported that excessive use of these insecticides in the public health and agriculture leads to environmental pollution causing a number of acute and chronic poisoning events (Lukaszewicz-Hussain, 2010). However, the prolonged use of insecticides has been known to reduce its effectiveness among the target insect pests. Thus, the need to search for novel insecticides with better efficacy or a new mode of action becomes evident.

Nowadays, mixed pesticides are in great demand for agricultural use because of their efficiency, convenience, and rapid actions (Zhou et al., 2011). One of the pesticides widespread in use is the combination of Organophosphate and Pyrethroid due to its low mammalian toxicity, less persistence, and rapid biodegradability in the environment (Singh et al., 2018). In the mixture of OP and Pyrethroid, OP inhibits the detoxification of Pyrethroid and increases the combined toxicity (Iyyadurai et al., 2014). Together, OP and Pyrethroid account for approximately 70% of the world market (Smagghe et al., 2009).

There is an increasing need for rapid and easily interpreted in vitro assays for screening the possible toxicity of pesticides (Eddleston et al., 2008; Papoutsis et al., 2012). The eventual purpose is to achieve an alternative system that allows for rapid testing of insecticides and to enable the accurate prediction of toxic efficacy at the whole animal level (Smagghe et al., 2009). Cell-based systems have proved to be useful for assessing toxicity and specific risk on target organs under chemical exposure, thereby offering high-level amalgamation on relations of chemicals with intact cells (Polláková et al., 2012; Yun et al., 2017). Therefore, cell-lines are considered as the perfect instrument for examining cellular toxicity. Many in vitro studies have demonstrated the toxicological effects of OPs on non-neural cells, which may be through a pathway other than their action on the central nervous system. Sf9 cell line, established initially from the pupal ovarian tissue of S. frugiperda, is an excellent model to study insecticide cytotoxicology and programmed cell death (Zhong et al., 2016).

Two insecticides, namely Ammo, and Profex, were selected in the present study to carry out the comparative assessment for their cytotoxic effects on insect Sf9 cell line. Ammo is a combination of Triazophos and Deltamethrin, and Profex is a combination of Profenofos and Cypermethrin. Cytotoxic effects of Organophosphate and Carbamate insecticides have been reported, such as oxidative stress, alteration of mitochondria function (Ahmed & Zaki, 2009; Maranet al., 2010). Toxic effects of Pyrethroids toward the cells include DNA damage, inhibition of mitochondrial complex I, and induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation (Naravaneni & Jamil, 2005; Patel et al., 2007) leading to cell mortality (Yang et al., 2016).

The mechanism by which pesticides cause damage involves multiple reaction pathways (Elhalwagy & Zaki, 2009). Both the increased production of reactive oxygen species and attenuation of the antioxidant barrier of the organism are likely to induce oxidative stress (Lukaszewicz-Hussain, 2010). Furthermore, studies with varying durations of exposure to Organophosphate or Pyrethroid pesticides have postulated that insects have evolved a complex antioxidant mechanism to overcome the toxic effects of ROS (Mittapali et al., 2007; Suh et al., 2010). The antioxidant defense is primarily constituted by the enzymatic actions, which include glutathione peroxidase (GPX), catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and ascorbate peroxidase (Barbehenn, 2002).

In this context, the present study is designed to evaluate the cytotoxic effects of Ammo and Profex on insect Sf9 cell line. The insecticides were selected as there is a lacuna for its toxic effect on Sf9 cell line and moreover, in vitro model is now considered to be the standard procedure to evaluate the toxic potential of newly synthesized pesticides.

Methods

Cell culture conditions

Sf9 was procured from NCCS, Pune, India, and was cultured in Grace’s insect medium (IML001, Himedia, India) supplemented with 10% FBS (RM1112, Himedia, India), 5 ml insect grace’s medium at 28°–30 °C. The medium was replaced with fresh culture media every 2–3 days.

Cell viability assay

The MTT assay was performed to find out the IC50 value and was based on the procedure described by Yu et al. (2016). In this assay, the yellow tetrazolium salt MTT was used as a substrate and reduced into purple formazan by mitochondrial succinate-dehydrogenase in viable cells only. Sf9 cell suspensions (1 × 106 cells/ml) were seeded onto a 96-well culture plates (100 μL per well). After 24 h of incubation, varying concentration of Ammo (Triazophos 35% + Deltamethrin 1%; Sudarshana company, India) and Profex (Profenofos 40% + Cypermethrin 4%; Nagarjuna company, India) were added (50, 100, 200, 300, 400 and 500 μg/ml) for 24, 48 and 72 h, and 0.1% DMSO was used as the control. Four hours before the assay, 10 μl of MTT (5 mg/ml in PBS) solution (TC191, HiMedia, India) was added to each well. To dissolve formazan crystals, the media in each well was replaced with 100 μl of DMSO (Himedia, India). The optical density was measured using a microplate reader at 570 nm with a reference wavelength of 630 nm.

Cell morphology assessment

For cell morphology, modified protocol of Yang et al. (2016) was followed. Sf9 cells (1.5 × 106 cells/ well) were plated in 6 well plates (TPC6, Himedia, India). After 24 h, cells were treated with the selected test chemicals for 12, 24 and 48 h. Cell morphological characteristics, such as cell shrinkage or swelling, membrane blebbing, were observed using inverted light microscope (Metzler M, India).

Apoptosis analysis by acridine orange/ethidium orange (AO/EB) staining

The dual staining of acridine orange and ethidium bromide was used to measure live cells from apoptotic and necrotic cells (Li et al., 2013). The cells (1 × 105 cells) were harvested and washed three times with PBS (pH 7.4) after being incubated with sub-lethal concentration 17.5, 35 and 70μL (LD, MD, HD) of the two test chemicals for 48 h. Cells were then stained with 20 μl of AO and EB (to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml for both) and incubated for 15 min at 37 °C in dark and washed three times with PBS (pH 7.4). The morphology of the treated cells was examined by fluorescent microscope (Floid cell imaging station (Invitrogen, USA)) with the excitation and emission wavelengths set 300 and 590 nm, respectively.

Intracellular ROS assay

The production of intracellular ROS was measured by oxidation of DCF-DA. Before the use, H2DCF-DA (D6883, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) stock solution was prepared in DMSO under a sterile condition in laminar flow hood and 1 × 105 cells were plated in the six-well plate. Cells were then treated with the sub-lethal concentration—HD, MD, LD for both the chemicals. After 48 h of treatment, the cells were centrifuged at 1000g for 5 min. Then, the cells were washed twice with PBS (pH 7.4). Cells were then incubated with DCFH-DA dye at 37 °C for 30 min to allow the fluorescent probe's diffusion into the cells and its subsequent hydrolysis to non-fluorescence dichlorofluorescein (DCFH) under the action of intracellular esterase. Intracellular ROS generation was measured by fluorescence microscopy (Floid cell imaging station (Invitrogen, USA)) with the excitation and emission wavelengths set 488 and 528 nm, respectively (Yu et al., 2016).

Antioxidant’s activity

ROS antioxidant enzyme activity in Sf9 cells was assessed in order to check the cytotoxic effects of the selected insecticides. The activity of antioxidants such as lipid peroxidase, glutathione-S-transferase and catalase was checked after (48 h) exposure to the sub-lethal concentrations (LD, MD, HD) of Ammo and Profex. Lipid peroxidase (LPO) levels were analyzed using the method of Beuge and Aust (1978). Glutathione levels were analyzed using the method of Beutter et al. (1963). Catalase activity was analyzed using the method of Sinha (1972).

Data analysis

Microsoft excel was used to determine the IC50 values from the dose response curve. Means of antioxidant activity were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Minitab software package. Significance was observed at p < 0.05 with the means compared using post hoc Tuckey’s HSD test at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

The cytotoxic effects of Ammo and Profex

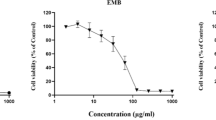

The viability of Sf9 cells treated with the increasing concentrations of organophosphates (Ammo and Profex) for 24, 48, and 72 h was assessed by MTT assay. The values obtained from MTT assay of 48 h of treatment with Ammo and Profex were used to find out the percentage (%) cell viability. The results showed that the Organophosphates inhibited cell vitality in a dose- and time-dependent manner at concentrations ranging from 50 to 500 µg/ml (Fig. 1a, b) for both the insecticides. The IC50 value for Ammo treatment at 48 h for Sf9 cells was 350 μg/ml (Fig. 1a), and that for Profex was 400 μg/ml (Fig. 1b). Toxicity bioassays showed that Ammo was more toxic for Sf9 (IC50 = 350 μg/ml) compared to Profex for Sf9 (IC50 = 400 μg/ml). However, to observe the alterations, three sub-lethal concentrations low, medium and high doses for Sf9 were selected for Ammo and Profex respectively (Table 1) for further studies.

Morphological alteration in Sf9 cells treated with Ammo and Profex

Sub-lethal treatment of Sf9 cells with Ammo and Profex resulted into a distinct alteration in the cell morphology compared to control and was found to be dose and time dependent (Fig. 2a, b). Maximum alterations, such as cell shrinkage and cell fragmentation, were observed at 48 h for both the insecticides.

AO/EB staining

As maximum morphological alterations were observed at 48 h, the rate of apoptosis on Sf9 cells were analyzed qualitatively as well as quantitatively using AO/EB fluorescent DNA binding dye at 48 h. The mean values of fluorescence recovery are represented in Fig. 3a, where the range of fluorescence is found to increase in time- and dose-dependent manner. The AO/EB staining results obtained are presented in Fig. 3b. The cells stained in green fluorescence represent AO staining while that in red/orange fluorescence exhibits EB staining. Treatment of Ammo and Profex resulted into a dose- and time-dependent alterations compared to control. The early apoptotic cell bodies displayed a bright green nucleus with condensed or fragmented chromatin and the late apoptotic cells characterized by condensed and fragmented orange chromatin. The cells initiating apoptosis also displayed shrinkage, rounding, and blebbing of the nuclear membrane. Of the two insecticides, Sf9 cells treated with Ammo show more significant cytotoxic impacts than Profex.

Results of acridine orange/ethidium bromide assay for Sf9 cells after treatment with sub-lethal concentrations (Low Dose, Medium Dose and High Dose) of Ammo and Profex. a Depicts the fluorescence (mean ± SE) in Sf9 cells after treatment with sub-lethal doses of Ammo and Profex for 48 h and stained with AO/EB. (p < 0.5*, p < 0.05**). b Show Sf9 cell treated with Ammo in an increasing concentrations of LD = 17.5 μg/ml, MD = 35 μg/ml and HD = 70 μg/ml and Profex with LD = 20 μg/ml, MD = 40 μg/ml and HD = 80 μg/ml in comparison to Control. Here, the yellow arrow indicates early apoptotic cells and the blue arrow indicates Late apoptotic cells

Intracellular ROS

The intracellular ROS level was analyzed qualitatively as well as quantitatively by fluorescence microscopy after incubation of Sf9 cells treated with Ammo and Profex with DCFH-DA (Fig. 4a, b). The mean values of fluorescence recovery are represented in Fig. 4a, where the range of green fluorescence is found to increase in a time- and dose-dependent manner. A dose-dependent increase in the ROS was observed in the Sf9 cells exposed to the LD, MD and HD of the test chemicals, suggesting that Ammo and Profex could induce ROS accumulation in Sf9 cells (Fig. 4b). Of the two test chemicals, Ammo exposure resulted into a relatively higher fluorescence than that of Profex.

Effects of sub-lethal concentrations of Ammo and Profex for the generation of ROS in Sf9 cells were determined by DCFH-DA staining. a Depicts the fluorescence (mean ± SE) in Sf9 cells after treatment with sub-lethal concentrations of Ammo and Profex for 48 h and stained with DCF-DA. (p < 0.5*, p < 0.05**) and b show Sf9 cell treated with Ammo in an increasing concentrations of LD = 17.5 μg/ml, MD = 35 μg/ml and HD = 70 μg/ml and Profex with LD = 20 μg/ml, MD = 40 μg/ml and HD = 80 μg/ml in comparison to control. Green fluorescence represents the intracellular ROS formed. Here, the yellow arrow pointing toward bright green nucleus indicates increased ROS level, cell membrane blebbing, and nuclear fragmentation

Antioxidant’s activity

The values obtained for the antioxidant enzyme assays are given in Table 2. The level of lipid peroxidase and Glutathione was found to increase significantly (p < 0.05) on exposure to sub-lethal concentrations of Ammo and Profex after 48 h (Table 2). On the other hand, the CAT activity was found to decrease in Sf9 cells after exposure to insecticides.

Discussion

Ammo and Profex, a combination of Organophosphate and Pyrethroid, are the most commonly used insecticides in the agricultural fields (Rice, Wheat, Maize, and Cotton) of India (Singh et al., 2018; Khanday & Dwivedi, 2018). Organophosphates such as Triazophos and Profenofos as single compound are well explored for its toxicity potential, however in combination with Pyrethroids such as Deltamethrin and Cypermethrin are lacking. In the present study, IC50 values obtained by MTT assay revealed that of the two compounds, Ammo (350 µg/ml) was more toxic compared to Profex (400 µg/ml), which might probably be due to Ammo's active components such as Triazophos and Deltamethrin which are reported to be highly toxic by various scientists (Kothalkar et al., 2015; Lal & Jat, 2015; Tomlin, 2009). Earlier studies conducted on relative toxicity of insecticides on insect pest have reported Triazophos to be more toxic compared to other compounds (Abou-Taleb et al., 2010; Balakrishnan, 1998; Bao et al, 2009; Martin et al, 2003). Furthermore, the MTT results revealed a time- and dose-dependent inhibition of Sf9 cell viability. Our results are in agreement with earlier reported work (Saleh et al., 2013) in which the cell growth inhibition rate of Sf9 cells was reported with various OP and Pyrethroids (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Sub-lethal exposure of Ammo and Profex resulted into a dose- and time-dependent morphological alterations such as cell shrinkage, nuclear degradation, increase in cell granularity in the Sf9 cells and was more profound with Ammo (Figs. 2a, b, 3b, 4b). Cell shrinkage and loss of cell sphericity indicate advancement for apoptosis (Zhang et al., 2016), which is accompanied by membrane blebbing, dissipation of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential, Cyt c release, DNA fragmentation and phosphatidylserine translocation (Plenchette et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2014). The altered dose-dependent morphology of the Sf9 cell line thus confirms that they are undergoing apoptosis, which was further authenticated by qualitative estimation using AO/EB staining. AO/EB staining with both the compounds confirmed the Sf9 cell line undergoing Apoptosis. Zhang et al. (2015) demonstrated similar results in Drosophila melanogaster S2 cells undergoing apoptosis on exposure to Fipronil. Thus, it can be concluded that both the insecticides are capable of inducing apoptosis in the Sf9 cells.

Apoptosis is an important homeostatic mechanism in cells that is characterized by cell shrinkage and condensation of nuclear chromatin (Johnson et al., 2000). AO/EB analysis results indicated that the proportions of apoptotic cells increased with increasing concentrations of both the compounds after 48 h of exposure. At the same time, a series of morphological changes including cell shrinkage and condensed and fragmented nuclei were observed. Thus, these preliminary observations suggest that Ammo and Profex induce the death of Sf9 cells through apoptotic pathways. Our results are in agreement with earlier work where various OPs and Pyrethroids have been reported to alter the morphology of cell lines (Karami-Mohajeri & Abdollahi, 2013; Huang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016; Mandi et al., 2020).

Intracellular ROS functions as a trigger of signalling molecules to initiate downstream events regulating cell differentiation, cell cycle, and apoptosis (Yu et al., 2016). However, excessive ROS production would impair and oxidize DNA and consequently result in the dysfunction of these molecules within cells leading to apoptosis (Li-Bo et al., 2012). ROS induces cardiolipin peroxidation in the mitochondrial inner membrane causing cytochrome-c release by breaching hydrostatic interactions (Chen et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2013). Thus, the results obtained in the present research using DCFH-DA dye, which is a colorimetric and fluorimetric probe was used for detection of oxidative species. A consistent dose-dependent increase in the production of ROS with increasing sub-lethal concentrations of both chemicals indicates that the dysfunction of mitochondria is probably inducing cell apoptosis via the generation of ROS. Therefore, to demonstrate the effect of Ammo and Profex in the generation of ROS, we first carried out the qualitative analysis of intracellular ROS. Our results are in agreement with previously reported studies where oxidative stress has been confirmed to involve in pesticide-induced cytotoxicity in SH-5Y5Y cells (Rabideau and Rabideau, 2001); in SF9 cell line (Saleh et al., 2013); in Tn5B1-4 cells (Luan et al., 2017); in UCR-Se-1 (Adamski et al., 2005); in Drosophila S2 cells (Zhang et al., 2015). Similar in vitro studies have shown the activation of intrinsic pathway of apoptosis in a p53 independent way on exposure to chlorella extract likes 2-chloroadenosine, resveratrol (Amin, 2009).

Oxidative stress by increased production of reactive oxygen species has been implicated in the toxicity of many pesticides (Bagchi et al., 1995; El-Demerdash, 2011). To confirm the role of Ammo and Profex in the production of ROS, the antioxidant defense system against the ROS in Sf9 cells was checked. The results revealed a significant increase (p < 0.05) in the GSH activity ensuing from the upregulation of reactive oxygen species on exposure to organochemicals. However, a substantial decrease in the CAT activity was observed in the Sf9 cells due to the overproduction of ROS under the oxidative stress generated by the OP. The probable mechanism by which the OP has expressed such activity is by inhibiting the activity of Sodium/Potassium ATPases, which in turn impairs cellular respiration and leads to an enhanced level of oxygen free radical (Adamski et al., 2005). The results confirm the role of active components such as Triazophos and Profenofos in enhancing the level of reactive oxygen species by inducing toxicity in Sf9 cells. Phosalone has been reported to have a pronounced effect on LPO, resulting in a decreased activity of CAT in vitro (Altuntas et al., 2003). Overproduction of ROS is known to induce oxidative stress unless it gets scavenged with endogenous antioxidants (Amin et al., 2006). Thus, overproduction of ROS would lead to the depletion of antioxidants or to the direct action of OP on the peroxidation reaction. OPs such as chlorpyrifos and diazinon have also proved to increase intracellular levels of ROS and LPO, which is modulated by intracellular GSH (Giordano et al., 2007). Thus in affirmation with the earlier studies, our present study confirms that both the OPs (triazophos and profenofos) irrespective of different active compounds have resulted in the generation of ROS. In addition, the level of LPO estimated in the Sf9 cells shows a significant (p < 0.05) increase in the LPO level, directly proportional to the increase in ROS. Similar results were obtained by Basu where in rat’s hepatic cells were found to induce non-enzymatic and enzymatic lipid peroxidation exposure to CCl4 (Carbon tetrachloride). CCl4 induced toxicity was found to enhance Lipid peroxidation by ROS, antioxidative nutrients, and various other factors that alleviate the biological membranes and cell structure in basal and pathological conditions (Basu, 2003). Lipid peroxidation is thus considered an essential indicator of oxidative damage of cellular components due to excessive generation of ROS, leading to several biological effects ranging from the alteration in signal transduction to gene expression and apoptosis oxidative stress development (Kannan & Jain, 2004).

Conclusion

In our study, both the OPs evoked ROS production within the Sf9 cells, which ultimately prompted cellular damage and triggered cell death. The Sf9 cells undergo ROS-mediated apoptosis. Therefore, it can be concluded that there is an existence of mitochondrial-dependent intrinsic pathway of apoptosis in the Sf9 cell line, prompted by two selected chemicals that are the combination of Organophosphate and Pyrethroid. However, further investigation is required to reveal the mitochondrial mechanisms and regulation of caspase activation during apoptosis. The present study was conducted in order to provide a basic knowledge for toxicity potential of chemicals at cellular level. Also, it is important to evaluate the environmental safety and risk factors of selected chemicals. Results suggest that both chemicals are highly toxic, which may cause detrimental effects on the surrounding environment and the non-target species.

Availability of data and materials

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AChE:

-

Acetylcholine Esterase

- AO/EB:

-

Acridine Orange/Ethidium Bromide

- CAT:

-

Catalase

- DCF:

-

Dichlorofluorescein

- DCFH-DA:

-

Dichlorofluorescein diacetate

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl Sulfoxide

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- GSH:

-

Glutathione

- HD:

-

High Dose

- LD:

-

Low Dose

- LPO:

-

Lipid Peroxides

- MD:

-

Medium Dose

- MTT:

-

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide

- NCCS:

-

National Center for Cell Science

- OP:

-

Organophosphate

- PBS:

-

Phosphate Buffered Saline

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic acid

- ROS:

-

Reactive Oxygen species

- Sf:

-

Spodoptera frugiperda

References

Abou-Taleb, H. K., Attia, M. A., & Rahman, S. A. (2010). Field performance and laboratory toxicity of five insecticides against black cutworm, Agrotis ipsilon (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Alexandria Science Exchange Journal, 31, 223–229.

Adamski, Z., Fila, K., & Ziemnicki, K. (2005). Fenitrothion induced cell malformations in vitro in Spodoptera exigua cell line UCR-Se-1. Biological Letters, 42(1), 41–47.

Ahmed, M., & Zaki, N. (2009). Assessment of the ameliorative effect of pomegranate and rutin on chloropyrifos-ethyl-induced oxidative stress in rats. Nature and Science, 7(10), 49–61.

Altuntas, I., Delibas, N., Doguc, D. K., & Gultekin, F. (2003). Role of reactive oxygen species in organophosphate insecticide phosalone toxicity in erythrocytes in vitro. Toxicology in Vitro, 17(2), 153–157.

Amin, A. (2009). Protective effect of green algae against 7, 12-dimethylbenzanthrancene (DMBA)-induced breast cancer in rats. International Journal of Cancer Research, 5(1), 12–24.

Amin, A., Hamza, A. A., Daoud, S., & Hamza, W. (2006). Spirulina protects against cadmium-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. American Journal of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 1(2), 21–25.

Bagchi, D., Bagchi, M., Hassoun, E. A., & Stohs, S. J. (1995). In vitro and in vivo generation of reactive oxygen species, DNA damage and lactate dehydrogenase leakage by selected pesticides. Toxicology, 104(1–3), 129–140.

Balakrishnan, N. (1998). Relative toxicity of certain insecticides to cotton whitefly (Bemisia tabaci Gennadius) and aphid (Aphis gossypii Glover) of Guntur strain. Doctoral dissertation, Professor Jayashankar Telangana State Agricultural University.

Bao, H., Liu, S., Gu, J., Wang, X., Liang, X., & Liu, Z. (2009). Sublethal effects of four insecticides on the reproduction and wing formation of brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens. Pest Management Science: Formerly Pesticide Science, 65(2), 170–174.

Barbehenn, R. V. (2002). Gut-based antioxidant enzymes in a polyphagous and a graminivorous grasshopper. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 28(7), 1329–1347.

Basu, S. (2003). Carbon tetrachloride-induced lipid peroxidation: Eicosanoid formation and their regulation by antioxidant nutrients. Toxicology, 189(1–2), 113–127.

Beutler, E., Duron, O., & Kelly, B. M. (1963). Improved method for the determination of blood glutathione. The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine, 61, 882–890.

Buege, J. A., & Aust, S. D. (1978). Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods in Enzymology, 52, 302–310.

Chen, Q., Wang, Y., Xu, K., Lu, G., Ying, Z., Wu, L., & Zhou, J. (2010). Curcumin induces apoptosis in human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells through a reactive oxygen species-dependent mitochondrial signaling pathway. Oncology Reports, 23(2), 397–403.

Eddleston, M., Buckley, N. A., Eyer, P., & Dawson, A. H. (2008). Management of acute organophosphorus pesticide poisoning. The Lancet, 371(9612), 597–607.

El-Demerdash, F. M. (2011). Lipid peroxidation, oxidative stress and acetylcholinesterase in rat brain exposed to organophosphate and pyrethroid insecticides. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 49(6), 1346–1352.

Elhalwagy, M., & Zaki, N. I. (2009). Comparative study on pesticide mixture of organophosphorous and pyrethroid in commercial formulation. Enviornmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 28(2), 219–224.

Giordano, G., Afsharinejad, Z., Guizzetti, M., Vitalone, A., Kavanagh, T. J., & Costa, L. G. (2007). Organophosphorus insecticides chlorpyrifos and diazinon and oxidative stress in neuronal cells in a genetic model of glutathione deficiency. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 219(2–3), 181–189.

Huang, J., Lv, C., Hu, M., & Zhong, G. (2013). The mitochondria-mediate apoptosis of Lepidopteran cells induced by azadirachtin. PLoS ONE, 8(3), e58499.

Huang, Z., Wang, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2015). Lethal and sublethal effects of cantharidin on development and reproduction of Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Journal of Economic Entomology, 108(3), 1054–1064.

Iyyadurai, R., Peter, J., Immanuel, S., Begum, A., Zachariah, A., & Jasmine, S. (2014). Organophosphate-pyrethroid combination pesticides may be associated with increased toxicity in human poisoning compared to either pesticide alone. Clinical Toxicology, 52(5), 538–541.

Johnson, V. L., Ko, S. C., Holmstrom, T. H., Eriksson, J. E., & Chow, S. C. (2000). Effector caspases are dispensable for the early nuclear morphological changes during chemical-induced apoptosis. Journal of Cell Science, 113(17), 2941–2953.

Kannan, K., & Jain, S. K. (2004). Effect of vitamin B6 on oxygen radicals, mitochondrial membrane potential, and lipid peroxidation in H2O2-treated U937 monocytes. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 36(4), 423–428.

Karami-Mohajeri, S., & Abdollahi, M. (2013). Mitochondrial dysfunction and organophosphorus compounds. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 270(1), 39–44.

Khanday, A. A., & Dwivedi, H. S. (2018). Phytotoxicity of organophosphates with particular reference to triazophos in the agriculture of India-A.

Kothalkar, R. R., Thakare, A. Y., & Salunke, P. B. (2015). Effect of newer insecticides in combination with Triazophos against insect pest of soybean. Agricultural Science Digest - A Research Journal, 35(1), 46.

Lal, R., & Jat, B. L. (2015). Bioefficacy and Persistence of Insecticides against Blister Beetle, Mylabris pustulata (Thunb.) in Pigeonpea, Cajanus cajan (L.) Mill sp. Pesticide Research Journal, 27(1), 57–62.

Li, B., Cao, Y. P., Feng, X. Q., & Gao, H. (2012). Mechanics of morphological instabilities and surface wrinkling in soft materials: A review. Soft Matter, 8(21), 5728–5745.

Li, S., Li, M., Cui, Y., & Wang, X. (2013). Avermectin exposure induces apoptosis in King pigeon brain neurons. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology, 107(2), 177–187.

Luan, S., Yun, X., Rao, W., Xiao, C., Xu, Z., Lang, J., & Huang, Q. (2017). Emamectin benzoate induces ROS-mediated DNA damage and apoptosis in Trichoplusia Tn5B1-4 cells. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 273, 90–98.

Lukaszewicz-Hussain, A. (2010). Role of oxidative stress in organophosphate insecticide toxicity—Short review. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology, 98(2), 145–150.

Mandi, M., Khatun, S., Rajak, P., Mazumdar, A., & Roy, S. (2020). Potential risk of organophosphate exposure in male reproductive system of a non-target insect model Drosophila melanogaster. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 74, 103308.

Maran, E., Fernández-FranŸon, M., Font, G., & Ruiz, M. J. (2010). Effects of aldicarb and propoxur on cytotoxicity and lipid peroxidation in CHO-K1 cells. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 48, 1592–1596.

Martin, T., Ochou, O. G., Vaissayre, M., & Fournier, D. (2003). Oxidases responsible for resistance to pyrethroids sensitize Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) to triazophos in West Africa. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 33(9), 883–887.

Mittapalli, O., Neal, J. J., & Shukle, R. H. (2007). Antioxidant defense response in a galling insect. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(6), 1889–1894.

Naravaneni, R., & Jamil, K. (2005). Evaluation of cytogenetic effects of lambda-cyhalothrin on human lymphocytes. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology, 19(5), 304–310.

Papoutsis, I., Mendonis, M., Nikolaou, P., Athanaselis, S., Pistos, C., Maravelias, C., & Spiliopoulou, C. (2012). Development and validation of a simple GC–MS method for the simultaneous determination of 11 anticholinesterase pesticides in blood—Clinical and forensic toxicology applications. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 57(3), 806–812.

Patel, S., Bajpayee, M., Pandey, A. K., Parmar, D., & Dhawan, A. (2007). In vitro induction of cytotoxicity and DNA strand breaks in CHO cells exposed to cypermethrin, pendimethalin and dichlorvos. Toxicology in Vitro, 21(8), 1409–1418.

Plenchette, S., Filomenko, R., Logette, E., Solier, S., Buron, N., Cathelin, S., & Solary, E. (2004). Analyzing markers of apoptosis in vitro. In Checkpoint controls and cancer (pp. 313–331). Humana Press.

Polláková, J., Pistl, J., Kovalkovičová, N., Csank, T., Kočišová, A., & Legáth, J. (2012). Use of cultured cells of mammal and insect origin to assess cytotoxic effects of the pesticide chlorpyrifos. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies, 21(4), 1001–1006.

Rabideau, C. L. (2001). Pesticide mixtures induce immunotoxicity: Potentiation of apoptosis and oxidative stress. Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Tech.

Saleh, M., Hajjar, J., & Rahmo, A. (2013). Effect of selected insecticide on insect Sf-9 cell line. Lebanese Science Journal, 14(2), 1–7.

Singh, S., Tiwari, R., & Pandey, R. (2018). Evaluation of acute toxicity of triazophos and deltamethrin and their inhibitory effect on AChE activity in Channa punctatus. Toxicology Reports, 5, 85–89.

Sinha, A. K. (1972). Colourimetric assay of catalase. Analytical Biochemistry, 47(2), 389–394.

Smagghe, G., Goodman, C. L., & Stanley, D. (2009). Insect cell culture and applications to research and pest management. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Animal, 45(3–4), 93–105.

Suh, H. J., Kim, S. R., Lee, K. S., Park, S., & Kang, S. C. (2010). Antioxidant activity of various solvent extracts from Allomyrina dichotoma (Arthropoda: Insecta) larvae. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology, 99(2), 67–73.

Tomlin, C. D. (2009). The pesticide manual: A world compendium (No. Ed. 15). British Crop Production Council.

Wang, Y., Yang, J., Chen, L., Wang, J., Wang, Y., Luo, J., & Zhang, X. (2014). Artesunate induces apoptosis through caspase-dependent and-independent mitochondrial pathways in human myelodysplastic syndrome SKM-1 cells. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 219, 28–36.

Yang, M., Xiang, G., Li, D., Zhang, Y., Xu, W., & Ta, L. (2016). The insecticide spinosad induces DNA damage and apoptosis in HEK293 and HepG2 cells. Mutation Research/genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis, 812, 12–19.

Yu, X., Zhang, Y., Yang, M., Gao, J., Xu, W., Gao, J., Li, Y., & Tao, L. (2016). Cytotoxic effects of tebufenozide in vitro bioassays. Ecotoxicology and Enviornmental Safety, 129, 180–188.

Yun, X., Huang, Q., Rao, W., Xiao, C., Zhang, T., Mao, Z., & Wan, Z. (2017). A comparative assessment of cytotoxicity of commonly used agricultural insecticides to human and insect cells. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 137, 179–185.

Zhang, B., Xu, Z., Zhang, Y., Shao, X., Xu, X., Cheng, J., & Li, Z. (2015). Fipronil induces apoptosis through caspase-dependent mitochondrial pathways in Drosophila S2 cells. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology, 119, 81–89.

Zhang, Y., Liu, S., Yang, X., Yang, M., Xu, W., Li, Y., & Tao, L. (2016). Staurosporine shows insecticidal activity against Mythimna separata Walker (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) potentially via induction of apoptosis. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology, 128, 37–44.

Zhong, G., Cui, G., Yi, X., & Zhang, J. (2016). Insecticide cytotoxicology in China: Current status and challenges. Pestic. Biochem. Phys., 132, 3–12.

Zhou, L., Huang, J., & Xu, H. (2011). Monitoring resistance of field populations of diamondback moth Plutella xylostella L. (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutidae) to five insecticides in South China: A ten-year case study. Crop Protection, 30(3), 272–278.

Acknowledgements

Authors are highly grateful to the Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science of The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda for providing laboratory assistance.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NP collected all relevant publications, wrote the manuscript and produced figure. BT and PP revised and formatted the manuscript. *PP read, formatted and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All the authors have their consent for the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Table S1. MTT assay was performed to find IC50 in Sf9 cells and the values of Mean ± SEM are given below. Here, n = 3, **p<0.05 as determined by One-way Anova.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pandya, N., Thakkar, B., Pandya, P. et al. Evaluation of insecticidal potential of organochemicals on SF9 cell line. JoBAZ 82, 60 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41936-021-00257-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41936-021-00257-4