Abstract

Background

Cryptococcosis is an infectious disease caused by encapsulated heterobasidiomycete yeasts. As an opportunistic pathogen, cryptococcal inhalation infection is the most common. While Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is extremely uncommon.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old woman with a history of rheumatoid arthritis on long-term prednisone developed a red plaque on her left thigh. Despite initial antibiotic treatment, the erythema worsened, leading to rupture and fever. Microbiological analysis of the lesion’s secretion revealed Candida albicans, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis. Skin biopsy showed thick-walled spores, and culture confirmed primary cutaneous infection with Cryptococcus neoformans. Histopathological stains were positive, and mass spectrometry identified serotype A of the pathogen. The patient was treated with oral fluconazole and topical nystatin, resulting in significant improvement and near-complete healing of the skin lesion within 2.5 months.

Conclusions

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis was a primary skin infection exclusively located on the skin. It has no typical clinical manifestation of cutaneous infection of Cryptococcus, and culture and histopathology remain the gold standard for diagnosing. The recommended medication for Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is fluconazole. When patients at risk for opportunistic infections develop skin ulcers that are unresponsive to antibiotic, the possibility of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis needs to be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Cryptococcosis is an infectious disease caused by encapsulated heterobasidiomycete yeasts, specifically Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii, which can infect the lungs, central nervous system, skin, and other body parts [1]. This fungus primarily affects immunocompromised individuals and is thus regarded as an opportunistic pathogen [2]. In 2003, primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) was confirmed as a distinct clinical entity, different from systemic cryptococcosis [3]. PCC is a primary skin infection caused by Cryptococcus species, occurring in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent hosts, often misdiagnosed due to its varied presentation [4, 5].

We reported a case of PCC in an immunocompromised patient with a long history of rheumatoid arthritis treated with prednisone. This study emphasizes the importance of considering PCC in the differential diagnoses of skin lesions in immunocompromised patients, highlighting the crucial role of histopathology and culture in diagnosis and the effectiveness of fluconazole in treatment.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old female, approximately one month ago, developed a red plaque measuring 1 cm in diameter on the left thigh, which was hardness and elevated skin temperature. The local hospital gave levofloxacin and cephalosporin. However, the erythema gradually increased and ruptured (Fig. 1A), and fever emerged half a month prior, with the highest recorded temperature reaching 38.7℃. The patient had a 20-year history of rheumatoid arthritis and was currently on a daily prednisone dose of 15 mg.

Upon admission, her white blood cell count was 7.2*10^9/L, with a neutrophil percentage of 87.0%. C-reactive protein was elevated at 18.6 mg/L. Autoimmune serology revealed an antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:80 (++), anti-Ro 52 antibody ++, and anti-SSB antibody +++. Microbiological analysis of the skin lesion’s secretion revealed the presence of Candida albicans, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE). No fungal growth was found, and no Mycobacterium tuberculosis was found in the tuberculosis smear. PPD test, T-SPOT test, G-test, and GM test were all negative. Bacterial soft tissue infection was suspected, and the patient received different continuous antibiotic treatment regimens (moxifloxacin, cephalosporin + neomycin, linezolid), but the ulceration area increased after 10 days (Fig. 1B).

Considering the possibility of pyoderma gangrenosum or a connective tissue disease, methylprednisolone was initiated at 40-60 mg/day, and some antibiotics were discontinued. Unfortunately, the ulcer did not exhibit improvement (Fig. 1C).

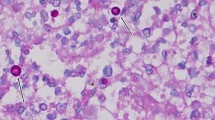

Subsequently, a skin biopsy was performed, revealing thick-walled spores on histopathological HE staining (Fig. 2A, B), and PAS and PASM staining were positive. Cryptococcus was cultured on Sabourarud weak agar medium (Fig. 2C), and ink staining was positive (Fig. 2D). Mass spectrometry analysis showed serotype A, indicating Cryptococcus neoformans infection (the pathogen is Cryptococcus neoformans) [1]. Further investigations, including head MRI plain scan + DWI, lung HRCT, and other examinations, showed no evidence of systemic infection (Figs. 3 and 4). (The patient declined lumbar puncture due to severe osteoporosis.) Diagnosis of primary cutaneous Cryptococcus neoformans infection was made [4].

We rapidly reduced hormones to prednisone 15 mg/day. Simultaneously, treatment with oral fluconazole (0.4 g qd) and topical nystatin was started, supplemented by local hypertonic dressing, resulting in significant improvement in the patient’s skin lesions within several days (Fig. 1D). After 3 weeks of antifungal treatment, the white blood cell count was 8.2*10^9/L, neutrophil percentage was 75.7%, and C-reactive protein was 1.9 mg/L.

The patient’s skin lesions were basically healed after maintaining the above antifungal treatment for 2.5 months, and no evidence of extracutaneous infection was found during this period, which confirmed our diagnosis. At discharge, the white blood cell count was 7.5*10^9/L, and the neutrophil percentage was 68%.

Discussion and conclusions

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC) was identified as a primary skin infection exclusively located on the skin, different from systemic cryptococcosis [3]. PCC is diagnosed both in immunocompromised and immunocompetent hosts [5].

Cryptococcosis was thought to be caused by various forms of C. neoformans, which should include both C. neoformans and C. gattii, according to the new classification. These two species are classified separately based on phylogenetic studies and the absence of genetic recombination between them [5, 6]. C. neoformans is the main pathogen in immunocompromised individuals, while C. gattii typically affects immunocompetent individuals [7]. C. neoformans is further classified into C. neoformans var. grubii (serotype A) and C. neoformans var. neoformans (serotype D), which can interbreed, forming AD hybrids [8].

Human infection usually begins with the inhalation of environmental basidiospores or desiccated yeast cells, which reach the pulmonary alveoli [8]. The primary adaptive immune response to Cryptococcus involves the stimulation of CD4 + T lymphocytes by dendritic cells, which secrete cytokines to recruit other lymphocytes and phagocytes to the infection site [7]. In immunocompetent hosts, antigen-presenting cells such as macrophages trigger cell-mediated immunity, leading to the elimination or containment of the fungi within granulomas [9]. However, in immunocompromised individuals, such as those with impaired CD4 + T cell function, the fungi can disseminate throughout the body, directly damaging immune cells and impairing the host’s immune response. Those most vulnerable to cryptococcal infections include HIV-infected individuals, solid-organ transplant recipients, and patients on chronic corticosteroid therapy [10].

Cryptococcal infection can also occur through direct inoculation of fungal forms into the skin, a route commonly associated with farming activities [8]. PCC is diverse in presentation. It can present with a broad range of lesions, including ulcers, plaques, cellulitis, abscesses, pustules, papules, blisters, nodules [11]. It can mimic conditions like pyoderma gangrenosum, molluscum contagiosum, Kaposi’s sarcoma, basal cell carcinoma, and others, depending on the patient’s HIV status [12]. Due to its diverse presentation, PCC cannot be diagnosed based on clinical manifestations alone; culture and histology remain the gold standards for diagnosis, although fine-needle aspiration has been suggested as a quick diagnostic method [5].

Treatment for PCC depends on the clinical form of cryptococcosis and the patient’s immunological and overall health status [8]. The recommended treatment for PCC is fluconazole 400 mg daily for 3–6 months or until healed [13].

This case highlights the importance of considering PCC in immunocompromised patients. Culture and histopathology are crucial for diagnosis, and fluconazole is the preferred treatment. However, this case has several limitations. It is a single case study, limiting the generalizability of the findings. The patient’s refusal to undergo a lumbar puncture due to severe osteoporosis prevented a thorough assessment of potential central nervous system involvement. Additionally, the treatment duration and follow-up were relatively short, leaving long-term outcomes and potential recurrence uncertain. Further studies with larger cohorts are needed to better understand PCC in immunocompromised patients.

Erythematous and ulcer on the outer side of the left thigh. (B) After 10 days of antibiotic treatment. (C) After 10 days of subsequent methylprednisolone treatment. (D) After 17 days of antifungal treatment, the secretions from the skin lesions were significantly reduced and the base surface was bright red

Data availability

Some or all data used during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Abbreviations

- PPD test:

-

Tuberculin purified protein derivative test

- SPOT test:

-

The T-SPOT test is a type of blood test used to diagnose tuberculosis (TB) infection. It works by detecting the presence of specific cells in the blood that react to TB antigens. This test is often used as an aid in diagnosing latent TB infection and active TB disease

- GM test:

-

Galactomannan test

- MRI:

-

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- DWI:

-

Diffusion Weighted Imaging

- HRCT:

-

High resolution computed tomography

- qd:

-

Quaque die

- PCC:

-

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis

- MRSE:

-

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis

References

Kwon-Chung KJ, Fraser JA, Doering TL, Wang Z, Janbon G, Idnurm A, Bahn YS. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii, the etiologic agents of cryptococcosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4(7):a019760. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a019760. PMID: 24985132; PMCID: PMC4066639.

Firacative C, Trilles L, Meyer W. Recent advances in Cryptococcus and Cryptococcosis. Microorganisms. 2021;10(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10010013. PMID: 35056462; PMCID: PMC8779235.

Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, Dupont B, Ronin O, Lortholary O, French Cryptococcosis Study Group. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(3):337–47. https://doi.org/10.1086/345956. Epub 2003 Jan 17. PMID: 12539076.

Gaviria Morales E, Guidi M, Peterka T, Rabufetti A, Blum R, Mainetti C. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis due to Cryptococcus neoformans in an Immunocompetent Host Treated with Itraconazole and Drainage: Case Report and Review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol. 2021;13(1):89–97. https://doi.org/10.1159/000512289. PMID: 33708089; PMCID: PMC7923711.

Du L, Yang Y, Gu J, Chen J, Liao W, Zhu Y. Systemic review of published reports on primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in Immunocompetent patients. Mycopathologia. 2015;180(1–2):19–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-015-9880-7. Epub 2015 Mar 4. PMID: 25736173.

Rathore SS, Sathiyamoorthy J, Lalitha C, Ramakrishnan J. A holistic review on Cryptococcus neoformans. Microb Pathog. 2022;166:105521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105521. Epub 2022 Apr 15. PMID: 35436563.

Muselius B, Durand SL, Geddes-McAlister J. Proteomics of Cryptococcus neoformans: from the lab to the clinic. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(22):12390. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222212390. PMID: 34830272; PMCID: PMC8618913.

Belda W Jr, Casolato ATS, Luppi JB, Passero LFD, Criado PR. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gatti in an Elderly patient. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7(9):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7090206. PMID: 36136617; PMCID: PMC9501260.

Campuzano A, Wormley FL. Innate immunity against Cryptococcus, from Recognition to Elimination. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof4010033. PMID: 29518906; PMCID: PMC5872336.

Srivastava GN, Tilak R, Yadav J, Bansal M. Cutaneous Cryptococcus: marker for disseminated infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015210898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2015-210898. PMID: 26199299; PMCID: PMC4513468.

Panza F, Montagnani F, Baldino G, Custoza C, Tumbarello M, Fabbiani M. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in an Immunocompetent patient: diagnostic workflow and choice of treatment. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(19):3149. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13193149. PMID: 37835892; PMCID: PMC10572633.

Christianson JC, Engber W, Andes D. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Med Mycol. 2003;41(3):177 – 88. doi: 10.1080/1369378031000137224. PMID: 12964709.

Chang CC, Harrison TS, Bicanic TA, Chayakulkeeree M, Sorrell TC, Warris A et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of cryptococcosis: an initiative of the ECMM and ISHAM in cooperation with the ASM. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024 Feb 9:S1473-3099(23)00731-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00731-4. Epub ahead of print. Erratum in: Lancet Infect Dis. 2024 Jun 27:S1473-3099(24)00426-2. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00426-2. PMID: 38346436.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient for her permission to publish this article and the institutional affiliations for supporting this effort.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82073425 and 82003332).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiong Zhou provided care for the patient and managed the case. Yan-jun Chu collected the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang University School of Medicine Second Affiliated Hospital (No. 2024-0060).

Consent for publication

The patient has given written informed consent for her personal and clinical details along with identifying images to be published in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chu, Yj., Zhou, J. A case of primary cutaneous Cryptococcus neoformans infection. BMC Infect Dis 24, 822 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09696-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09696-0