Abstract

In an era where brands try to generate strong and positive consumer responses in an uncertain, complex, unpredictable, and fast-changing environment, understanding the mechanism that brand signals turn to external audiences’ responses has become ever more important. Using as a context service brands, given their complexity, this work aims to update and inform existing knowledge on brand building practices, audience-processing and the brand-related action link. The proposed conceptual brand building and audience response framework is based on an extensive review of existing brand management and services marketing academic knowledge collected and examined aiming to: (a) synthesise the somewhat dispersed literature on firms’ brand building and audience-processing and brand-related action link reported in both literature streams and (b) identify relevant trends on brand building and audience-processing/responding. The introduced framework comprises three components (the chain, the influencing factors and the feedback loops), provides a good, contemporary overview of the full brand identity co-creation process and potential audience behavioural responses and unfolds avenues for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Brands are offers’ perceptions in the minds of individuals (de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 2000). Firms engage with branding practices aiming to develop, support and cultivate strong brands. Strong brands typically enjoy depth and breadth of brand knowledge (Keller 2003, 2016), high levels of awareness and recognition, well-established, clear associations and high differentiation, which elicit important benefits for firms by creating external audiences’ fiercer cognitive, emotional and behavioural responses (Chatzipanagiotou et al. 2016; Veloutsou et al. 2020).

Branding, the firm’s marketing practices creating and supporting brand promises over time (Veloutsou 2022), incorporates the internal brand meaning design and the development and execution of brand programmes (direct or indirect signalling activities), aiming to position the brand in the minds of individuals and evoke brand-related perceptions, feelings and behaviour. Given their importance, brands should be a key consideration in any strategic plan and provide direction to business decisions and action. Firms should set objectives and performance measures for their marketing and other campaigns by understanding the process by which brand strategies and tactics trigger diverse, external to-the-company audiences’ responses, thus creating brand value for brands.

Broad conceptual frameworks and empirical models aiming to explain the brand building company value-creation connection were introduced long ago and are extensively based on the attitude-behaviour link. Some of this work is specifically focused on services as a context, because its characteristics can provide richer brand building insights for the brand building process (Blankson and Kalafatis 1999; de Chernatony and Segal-Horn 2003; O'Cass and Grace 2004; Veloutsou 2022). Most of the existing brand building work reports a positive results-generating process with customer response outputs including brand reputation (Veloutsou 2022; Veloutsou and Delgado-Ballester 2018), intention to use (O'Cass and Grace 2004), brand attachment (Lehmann et al. 2008), brand loyalty (Keller 2001, 2016) or outcomes labelled brand equity (Berry 2000) but primarily using loyalty statements (Chatzipanagiotou et al. 2016; Veloutsou et al. 2020). Other similar work illustrates mechanisms behind financial value creation/impact (Keller and Lehmann 2003, 2006; Keller 2016) or brand growth (Huang and Dev 2020).

The reported brand building and audience behaviour link literature is extensively based on systems theory (Padela et al. 2023), positively response-valenced and mostly dated or not unveiling the full complex process. Some of the existing academic engagement focuses on specific, smaller functions of the overall signal-processing-outcome process (Blankson and Kalafatis 1999; Huang and Dev 2020; Veloutsou 2022; Veloutsou and Delgado-Ballester 2018), others present broad categories of factors without detailed explanation of their specific elements (Keller 2001, 2016; Padela et al. 2023) or/and a selected and often limited number of contributing factors/elements (Berry 2000; Chatzipanagiotou et al. 2016; de Chernatony and Segal-Horn 2003; Fetscherin et al. 2021; Lehmann et al. 2008; O’Cass and Grace 2004; Veloutsou et al. 2020). Other reported work has a somewhat different focus, for example, aiming to understand the creation of financial outcomes (Keller and Lehmann 2003; Keller 2016), define relevant terms (Brown et al. 2006) or generally organise the literature (Christodoulides and Wiedmann 2022). Originally introduced over two decades ago, the mainstream brand building academic work is, at large, produced by Keller (2001) and supported today without any adaptation (Keller 2016), except the appreciation that brand building needs to consider the brand origin (brand history and heritage) and present position (values, personality and character) to design the brand future (brand mission, vision and purpose) (Keller 2023). Services-specific work on this area is reported mainly from two research teams, specifically from de Chernatony, Dall’Olmo Riley and Segal-Horn, and Blankson and Kalafatis, but not adequately informed from mainstream perspectives (Keller 2001; Keller and Lehmann 2003; Huang and Dev 2020).

The brand building body of knowledge does not take into consideration advancements in branding. Brands and branding evolve over time (Brodie and de Chernatony 2009; Padela et al. 2023; Veloutsou and Guzmán 2017) and the offer delivery and experience has, in many ways, fundamentally changed in recent years for some complex contexts like services (Ostrom et al. 2015). Firms need to develop, adjust and signal their brand identities to external audiences, who receive images forming brand reputations (de Chernatony 1999), but also adapt and evolve their branding practices to keep pace with environmental changes (Swaminathan et al. 2020). Current academic engagement lacks an updated integrative reporting of a brand’s development process incorporating recent advancements in the field, such as the never fully stabilised brand meaning (Price and Coulter 2019), the active, substantive and diverse involvement of external actors in brand creation (Black and Veloutsou 2017; Iglesias et al. 2023), the constant informing of the internal brand meaning (brand identity) to the external brand meaning (brand image and brand reputation) (Urde 2013), the increase in the speed of change (Swaminathan et al. 2020), the wider societal brand purpose (Keller 2023; Iglesias et al 2023; Lückenbach et al. 2022; Williams et al. 2022) and the loss of company control in brand building (Price and Coulter 2019). Furthermore, overlooked consumer responses advancements include the recently recognised brands’ impact on the personal, interpersonal and group consumer self (Bagozzi et al. 2021), personal audience’s considerations, such as ethics (Bhargava and Bedi 2021), or the polarity in brand-related responses (Fetscherin et al. 2019; Dessart and Cova 2021; Osuna-Ramírez et al. 2019) that can change in direction over time (Parmentier and Fischer 2015).

The relevant research mostly features brand building as an action that consumers will respond to, not considering them, and many other stakeholder audience groups, as brand co-creators. The existing approaches also underreport the complexity of brands’ signalling transformation into external actors’ responses and does not consider changes in the environment and the role of brands for their customers. The emerging and important issues associated with the brand meaning development support the need to revisit brand building and its effect to audiences (Brodie and de Chernatony 2009) and a broad and inclusive literature engagement can enlighten the process and help our understanding of the phenomenon (Rumrill and Fitzgerald 2001).

The purpose of this paper is to enhance our understanding of the brand building processes and audiences’ response as a domain (Kraus et al. 2022) via an integrative review of the existing literature informed by the views of academic and practitioner experts. As expected from integrative review papers (Palmatier et al. 2018; Rumrill and Fitzgerald 2001) and using as a context a complex offering, services, this work reviews and synthetizes existing literature linking brand building practices with audience-processing and brand-related action. Following common integrative reviews appropriate for mature topics practice (Snyder 2019), this work gestates knowledge by honouring, connecting, adapting and extending extant knowledge (Jaakkola 2020; Post et al. 2020) from different studies, a task recognised as important and long overdue for this topic (O’Cass and Grace 2004). By incorporating emerging state-of-the-art brand building aspects and introducing a contemporary framework, this work builds theory by providing intellectual insights and allowing us to rethink, put a conceptual order and articulate the process of the brand building’s enactment and continuous production and reproduction (Sandberg and Alvesson 2021).

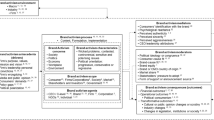

The proposed brand building and audience response framework comprises three components: (1) the brand building and audience response chain that initiates the brand building; (2) the influencing factors that moderate/activate the chain components; and (3) the feedback loops that allow the reaction and adjustment of the chain components. The framework advances our outdated approach by resolving inconsistencies and adding fresh and contemporary brand building insights into the process of brand building, approaching brands as mobbing assemblages (Price and Coulter 2019) created through interactions between the building blocks, the stakeholders involved and influential factors. Specifically, the framework incorporates moderators’ feedback loops, accounting for the process-facilitating factors and unfolding brand co-creation, thus contributing to our theoretical understanding of the phenomenon (Cropanzano 2009; Hulland and Houston 2020). The paper also discusses wider implications and usefulness of the proposed framework for branding research.

What follows is an outline of the choice of the context and process used to engage with the existing body of knowledge. The paper continues with the presentation of the brand building and audience response framework, and, finally, discusses implications for theory and practice related to this framework.

Methodological choices

Choice of the context

Researchers have long recognised that brand building principles are the same for all offers, but services idiosyncrasies make brand building execution more demanding and complex and often the chosen context for brand building research (Blankson and Kalafatis 2007; de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 1999; de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 2000; de Chernatony and Segal-Horn 2003; Iglesias and Ind 2020). Services brands are typically associated with the corporate offer (Berry 2000), portrayed as closer to the services end in the product-service continuum than other offers (de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 1999; de Chernatony and Segal-Horn 2001), come alive via firm–consumer interactions and high (de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 2000) or low (Ostrom et al. 2015) human contact and have specific characteristics, namely intangibility, inseparability of production and consumption, heterogeneity of quality and perishability (Blankson and Kalafatis 1999; de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 1999; de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 2000; de Chernatony and Segal-Horn 2001). Services brands’ features make their consumption primarily experience-based (Chevtchouk et al. 2021), involving many diverse online and offline interactions with external audiences (de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 1999; de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 2000), higher than most other offers (Jaakkola et al. 2015).

The extent of service brands’ differences from other brands has led some researchers to deviate from the mainstream view and suggest that a distinct brand building approach should support them (Huang and Dev 2020). These researchers (Huang and Dev 2020) identified, and organised under various labels, their driving growth factors and in particular: relationship (good value, reliable, cares about customers, trustworthy and helpful), quality (leader, high performance, intelligent and socially responsible) and personalisation (different, unique, dynamic, innovative and distinctive). Overall, the services brands’ consumption introduces challenges that allow investigation of their brand building and its response to unveil more detailed aspects and processes, applicable all highly complex or less complex offers and can help brands operating in any context.

Engagement with the existing body of knowledge

Starting from methodological literature suggestions highlighting that the researchers’ exposure, expertise and experience are key in the process (Kraus et al. 2022; Snyder 2019; Torraco 2005) and following methodological advice on conceptual model building (Jabareen 2009), this integrative literature review is based on papers reporting relevant frameworks and models and papers challenging their existing components and their reported links and papers introducing new notions not explained from and incorporated in existing frameworks. This work identified existing academic output informing the development of the suggested framework, from an extensive search on the broad related topics as reported in the existing body of academic knowledge based on the expertise and reading of the researcher coordinating the framework development and many academics and practitioners exposed to earlier framework versions. The development of the framework utilised three processes, each consisting of specific steps (Fig. 1) and took a period of about 6 years from the initial stages of literature engagement to its completion.

The first process (Process A) aimed to identify the sources. To identify work of the appropriate breath of knowledge (Cropanzano 2009), the three-step (Steps 1–3) literature search, started from the narrow base of existing knowledge on the topic, moved to identify broader changes in the wider areas to finally identify and examine literature linking the changes and trends within the narrow topic. Step 1 aimed to identify key sources on the brand building process or sub-processes reported in the literature. Academic databases, articles and books were searched on Scopus for its high academic standard, given the higher quality and inclusivity of marketing content than other academic databases (Ferreira et al. 2016; Strozzi et al. 2017), and Google Scholar for its inclusivity. Step 1 produced several conceptual and empirical papers primarily on brand building and service brand development, but also identified work on brand building in other contexts (Table 1), leading to the construction of a first set of publications of interest. Step 2 detected academic work on trends and developments in branding and services and areas influencing the complexity of the brand building process, with a focus on work reported after 2010. Academic databases, articles and books returned several pieces focusing on the evolution of branding and services, some also suggested at a later stage by academic experts (Table 2). Step 3 identified additional work outlying the brand and service specific areas of evolution. The selection of these sources was based on their relevance to the brand building process enhancement.

The identification of sources in all Process A steps followed a similar approach as other work trying to uncover trends in a body of literature (Siano et al. 2022a). Papers were identified and read in many rounds and dynamically. Specifically, after the first search, supplementary to the original topics/aspects, papers on new topics were considered after the presentation of earlier versions of the framework and discussions with experts during Process C, or as new academic work was produced, leading to the identification of additional reading. To avoid the danger of entropy of the collected material and complicate the overall reading of the literature informing this study (Snyder 2019), the selection and collection of papers for each one of the topics/aspects stopped when saturation in terms of a clear understanding of a trend’s effects on the brand building process for each examined potential framework component in Step 3 was reached (Dekkers et al. 2022).

The second process (Process B) focused on the engagement with the literature and consisted of two steps (Steps 4–5). In Step 4, various papers were analysed and interpreted. The papers identified in Step 1 were first read and summarised, paying particular attention to each paper’s year of publication, authors, theories and reported frameworks. The papers identified in Step 2 were then read, where changes and trends both in the environment and the brand and service thinking were detected. Finally, the papers identified in Step 3 were read, and relevant notes were taken. In Step 5, the relevance of the previously reported components and the newly recognised in the literature trends to the brand building process was assessed. Following the methodological literature guidelines (Jabareen 2009; Kraus et al. 2022), the engagement with the debates, unexplored knowledge areas and making sense of the arguments led to theorization. Specifically, components were classified and their potential function in the process and relationships with other framework components were considered.

Process C integrated the research and the development of the framework with the help of experts and consisted of one step (Step 6). Relevant components from the previously reported brand building processes identified in step 1 were considered as the initial framework basis. Components emerging from trends identified in steps 2 and 3 deemed appropriate were introduced in the process, resulting to numerous framework versions and leading to the first full drafted framework discussed with experts both publicly and privately. Public framework presentations in academic research seminars and keynote speeches in academic conferences in various countries and in practitioner events, and private presentations of the drafted framework via face to face or videoconference discussions with key experts and in executive MBA sessions were conducted. Participants were allowed to offer their views on the presented framework and suggest additional literature or framework components based on their experience. All suggestions were considered, leading to more reading and notes from the literature (back to Steps 4 and 5). Additional adjustments were made based on the reading and discussions with the people who made the suggestions. In total, about 35 presentations of earlier versions of the conceptual framework were conducted to help validate this work (Jabareen 2009). The suitability of the elements retained in the framework was assessed based on the relevance and impact of the constructs/aspects that emerged from the discussions in the brand building process. The various rounds of adjustments informed the conceptual framework components retained.

In summary, the three processes and their steps were interconnected. The identified material for analysis in Process A (Steps 1–3) was gradual. After reading the originally identified material during Process B (Steps 4–5), new ideas and aspects were identified. Processes A and B were repeated resulting in the emergence of drafted frameworks in Process C (Step 6). Drafted frameworks were discussed with experts, who suggested adjustments and additional components for consideration, and thus new literature was identified (Process A) and read (Process B) leading to revised and improved frameworks (Process C). This process was repeated until no additional changes were suggested during five interactions with experts. The resulting framework is presented herein.

The brand building and audience response framework

Aiming to develop the brand building and audience response framework, this section first defines the terms brand, brand meaning, the components of brand meaning and then presents the framework consisting of three main components: the audience response chain, the influencing/moderating factors and the feedback loops.

Researchers appreciate that the term brand is broader than what some of the early literature reported (Brodie and de Chernatony 2009; Conejo and Wooliscroft 2015; Gaski 2020; Veloutsou and Delgado-Ballester 2018). Brands are entities incorporating all offer attributes characteristics, rational and emotional characteristics (de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 1999) and human-like characteristics and fundamental values ascribed to each brand by people (Veloutsou & Guzmán 2017). In particular, brands in this work are seen as “evolving mental collections of actual (offer related) and emotional (human-like) characteristics and associations which convey benefits of an offer identified through a symbol, or a collection of symbols, and differentiates this offer from the rest of the marketplace” (Veloutsou and Delgado-Ballester 2018, p. 256). Brands may reside as passive objects with utilitarian and symbolic meanings, relationship partners and regulators of personal relationships or as creators of social identity with social group-linking value (Bagozzi et al. 2021). Given their importance, brands’ existing and desired brand meaning, and the influence of the company-controlled and uncontrolled actions on the brand meaning, should drive all company decision-making.

Brands are complex entities, semiotic systems, living in the minds of individuals, capable of retaining various degrees of meaning and scope (Conejo and Wooliscroft 2015) that allow them to be attractive to different segments (Guzmán et al. 2006). Brand meaning is a broad term embracing all mental brand-specific connotations, brand associations, without signifying the group of people that has these connotations in their minds (Black and Veloutsou 2017; Lückenbach et al. 2022; Vallaster and von Wallpach 2013).

After reviewing the literature (Aaker 1996; Keller 2001, 2016), this work suggests that a brand’s meaning typically contains a combination of specific broad brand attributes and, in particular, symbol, product and person attributes, and the brand functions expressed through user and usage imagery brand associations. This work also updates some of the original definitions of these categories. The brand as a symbol is what represents the brand (Aaker 1996), such as the marks, objects or characters conventionally representing an abstract offer, which may include attributes such as the brand name, logo, colour, sound, fonts, scent, any created character or other attributes that could be received through human senses. The brand as a product is the associations with the attributes of an offer that aims to satisfy wants or needs such as physical goods, services, experiences, events, persons, places, organisations, information, ideas or any such combination (Kotler 2003). The brand as a person is the set of human characteristics associated with the brand answering the question “if the brand were a person, what type of person would it be?” (Veloutsou and Taylor 2012) and may include various human-like aspects including brand personality, gender, age, social class, values, nationality (country of origin), networks (friends and enemies), heritage/history, dreams or any combination of these attributes (Keller 2023; Veloutsou and Taylor 2012). User imagery concerns the perception of the type of person using the product or service (Keller 2001, 2016). Finally, experience imagery incorporates any situational factors related to brand usage and experience, such as the time of day, week, or year, location, or the type of activity that the offer is used (Keller 2001, 2016), but also what is expected from the offer in other brand interaction (Chevtchouk et al. 2021).

The brand building process aims to develop and support a consistent brand meaning across different groups and involves the design of a firm’s desired set of connotations and associations (brand identity) and the signalling of a selected subset to external audiences aiming to create and sustain this set of symbols and associations in the minds of external audiences (brand images and brand reputations) (Veloutsou and Delgado-Ballester 2018). A brand’s meaning in the mind of an individual is constructed from brand notions developed through any direct or indirect incidents that provide information, is updated over time, and leads to the development of assessments, feelings and actions.

The brand building and audience response framework proposed herein unfolds the process of turning the firm’s brand building into the audience’s brand action and consists of three components (Fig. 2). The first component is the brand building and audience response chain comprising specific building blocks and is presented in the middle part of Fig. 2. The second component is the influencing factors that act as moderators supporting the activation of the components of the blocks of the chain and features on the top on Fig. 2, where the relevant factors are presented in boxes. The final component is the feedback loops that transmit signals to and update the previous blocks of the chain. Detailed presentation of each one of these components follows, represented as the arrows on the bottom of Fig. 2.

The building blocks of the brand building and audience response chain

The brand building and audience response chain encompasses four building blocks: (1) internal brand meaning (2) market brand meaning, (3) market brand mindset and (4) market action. Each building block has a specific function and includes various elements. All four building blocks are presented in the middle part of Fig. 2.

Internal brand meaning

The internal brand meaning block explains the brand design firm-managed processes based on the brand meaning as understood from the team managing the brand (brand identity).

The branding process starts with a firm devising a particular branded offer (de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 1999) and the development and support of a unique set of internally agreed brand associations or brand positioning attributes (brand identity) that the brand aspires to create or maintain (Aaker 1996). For a newly introduced brand, the brand meaning development starts from a firm and its employees who design and deliver the offer through consistent branding building (Chung and Byrom 2021). Designing and delivering innovative offers and understanding the organisation and employee issues during the process are key priorities for services research (Ostrom et al. 2010, 2015).

The internal cross-functional support team’s understanding of the brand’s meaning is the brand identity defined as “the symbols and the set of the brand associations that represent the core character of the brand that the team supporting the brand aspire to create or maintain as identifiers of the brand to other people” (Veloutsou and Delgado-Ballester 2018, p. 256), to be coherent and consistent over time (Abratt and Mingione 2017). As the brand identity is designed, the brand purpose, the long-term central brand aim linked with the greater value that the brand can directly or indirectly create for the society over and above profit making, is also realised and considered (Keller 2023; Iglesias et al. 2023; Williams et al. 2022). The principles of the brand purpose should drive the brand identity design.

The brand support team has a “voice” that significantly influences the design and delivery of the offer (Ostrom et al. 2015). The brand identity design follows a four-phase process: establishing a clear brand identity strategy; designing and selecting sensory identity; aligning organisational identity; and delivering brand identity through external communication (Chung and Byrom 2021) that should arise from the brand’s purpose (Kapitan et al. 2022; Lückenbach et al. 2022; Williams et al. 2022) and clearly express what the brand is (symbol, product and person) and what the brand does (user and experience imagery). During a specific brand’s meaning design, the brand development team is expected to recognise the most important brand attributes, named in the literature core, essence, mantra, kernel or big idea, and peripheral attributes (extended core) that will be supported with the aim to build associations (Urde 2016). The associations can be primary, originating from what the brand itself stands for and its purpose, or secondary, originating from other entities and objects linked to the brand (Bergkvist and Taylor 2016; Keller 2003). Knowing that consumers value the core offer and the brand experience (O’Cass and Grace 2004) and considering the wider organisational values and identity (Martin and Hetrick 2006; Urde 2013) and the characteristics of other firms’ brands, the brand’s support team seeks to design and manage offers with excellent characteristics (Jaakkola et al. 2015), clearly defined brand promise, values, vision (Aaker 1996; Urde 2016) and differentiation.

The brand positioning attributes are based on internally shared (Aaker 1996; de Chernatony and Segal-Horn 2003) in-depth knowledge of what the brand should stand for (Chung and Byrom 2021). Although having a shared internal understanding of the brand’s meaning is important and wanted (Balmer and Podnar 2021; de Chernatony and Segal-Horn 2003), reality is that the perceived brand identity may diverge among different groups of employees because of hierarchical lines or personal experiences (Sarasvuo 2021). Employees from various departments participate in the brand identity design, playing varying roles in different brand design phases (Chung and Byrom 2021) and delivery, driving positive experiences (Ostrom et al. 2015). Internal communications and formal and informal training can facilitate the development of an internally shared understanding of the brand identity and its importance (de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 2000; Ostrom et al. 2010), that allows the delivery of well-designed (Ostrom et al. 2010), consistent in quality (de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 1999) offers. The importance of human resource initiatives, in terms of brand training and developing skills to consistently support brand identity, is so high that they have been incorporated as a part of brand identity by some researchers (Coleman et al. 2011; Tourky et al. 2020), a view not supported from the brand building and audience response framework.

Market brand meaning

The result of brand building is expected to be a brand that resides in consumers’ minds (Chung and Byrom 2021; Urde 2013); the market brand building block explains what this involves. The audience needs to reach brand-related information to build brand knowledge and form brand meaning (brand image and brand reputation), with various audience members likely to have varying depth and breadth of information and likely to experience the brand via different channels. To understand the process within the brand building block, relevant terms (brand identity and brand reputation) are defined.

Miscellaneous complex and diverse offering’s brand signals present the brand and project and confirm its promises to external audiences (Blankson and Kalafatis 1999; Keller and Lehmann 2006). The diverse and repeat interaction with controlled or semi-controlled touchpoints and channels during the full consumers journey (Keller 2003; Veloutsou 2022), such as with employees (i.e. de Chernatony and Segal-Horn 2003; Keller and Lehmann 2006; Yani-de-Soriano et al. 2019), technology (i.e. Ostrom et al. 2015; Kabadayi et al. 2019), any form of massive or private communication (Blankson and Kalafatis 2007; Parmentier and Fischer 2015; Pink et al. 2023) and the actual consumption of the brand (i.e. Xu et al. 2019) are key contributors to the development of perceptual brand associations and meaning (Berry 2000; de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 1999; Veloutsou 2022). The interactions vary in interactivity; more interactive interchanges tend to be more influential (Albert and Thomson 2018). The importance of identity signalling is featured by some as a part of brand identity (Coleman et al. 2011; Tourky et al. 2020), although the brand building and audience response framework presented here does not support this view.

The literature highlights ambiguity in the terms used to capture brand meaning in the minds of various audiences (Brown et al. 2006; Dowling 2016; Stern et al. 2001; Veloutsou and Delgado-Ballester 2018) and extensively uses the term brand image to label all external audiences’ brand perceptions (Stern et al. 2001; Parris and Guzmán 2023). Brand associations may vary in the minds of different individuals external to the firm in various ways, including the object evaluated (interaction or overall brand perception) and the characteristics considered (Guzmán et al. 2006; Plumeyer et al. 2019). A closer look at the brand building and audience response chain, and in particular the market brand meaning block, reveals a sub-process allowing different external brand meanings to be generated and mentally managed by miscellaneous audiences.

Focusing primarily on the core brand identity attributes (Urde 2016) and attempting to position the brand in external audiences’ minds, the brand support team uses primarily marketing tactics to develop experiences and project and publicise the internally shared set of symbols, associations and promises (brand identity) to the market (Chung and Byrom 2021). Firm-controlled brand signals are received and processed by consumers who form mental images and specific brand-related perceptions resulting from the content of each particular encounter (brand image) (Veloutsou 2022). Brand image is the “perception formed to the mind of a member of the external audience about the brand after one real or mental encounter with the brand” (Veloutsou and Delgado-Ballester 2018, p. 256). Brand images are the understanding of the projected through brand actions and communication characteristics, produced through direct and indirect interactions (Padela et al. 2023), or experiences (Chevtchouk et al. 2021), before, during or after the actual engagement with the brand. Brand images require effort to build since it requires the production of signals showing external firm audiences what the brand stands for (Brown et al. 2006). Because of their intangible nature, services brands often capitalise on clues associated with their physical evidence as a vehicle for communicating their values (de Chernatony and Segal-Horn 2003), with the recent enhancement of technology-enabled interactions (Ostrom et al. 2015) contributing to the brand experience.

External audiences’ brand interaction and signals develop images, informing the brand as a symbol, product and person, and user and experience imagery knowledge. The totality of the gained brand knowledge forms brand reputation, the “accumulation of brand images and is an aggregate and compressed set of public judgments about the brand” (Veloutsou and Delgado-Ballester 2018, p. 256). Brand reputation is the standardised and somewhat stable long-term positioning of the brand in audiences’ minds and its esteem, built, earned and proven in time, reflective of the history and the brand’s past actions, represent the total brand perception (Brown et al. 2006; Highhouse et al. 2009; Rindova et al. 2007). The various functional, symbolic and experiential benefits consumers expect from the brand (Aaker 1996; Keller 1993; Lückenbach et al. 2022), such as quality, performance, innovativeness, distinctiveness/differentiation or the overall contribution of the brand in the society and the wider environment, are brand knowledge that also positions the brand in the minds of external audiences. The perceived brand benefits are expected to support the intended brand purpose.

The strength and depth of brand knowledge, the share of mind or the amount of knowledge of brand meaning attributes (Keller 1993), ranges from awareness to knowledgeableness (Fetscherin et al. 2021). Consumers able to simply recognise or recall some or all of the brand meaning attributes are in the brand awareness stage, the lowest brand knowledge depth stage. Consumers in the middle brand knowledge stage, brand familiarity, possess more brand meaning attributes’ information, but this knowledge is incomplete. Finally, consumers demonstrating deep understanding and wisdom in relation to the brand characteristics are in the stage of brand knowledgeableness. When a brand’s specific characteristics are thought of easily and often, this clearly indicates that this brand holds a larger share in consumers’ minds. The depth and breadth of brand knowledge indicates the brand meanings’ strengths in the minds of external audiences (Keller 2001, 2016). However, even when the brand knowledge is extensive, the brand meaning block allows a low overall breadth of brand impact to individuals and is relevant only to the personal self (Bagozzi et al. 2021).

Brand reputation is reconsidered every time individuals receive new brand-related signals which either reinforce or weaken the signals’ power. The accumulated knowledge infuses the brand signals’ decoding to images and the degree to which new images inform and adjust the previously existing reputation.

Market brand mindset

The processes in the market brand mindset block are based on the assessment of the brand-associated benefits, or value (Swaminathan et al. 2020). The market brand mindset is formed after the processing of the market brand meaning (brand images and brand reputations) and consists of rational (brand assessment) and affective (brand feelings and brand relationships) elements. These elements have polarity, are related with brand strength and attitudinal consumer-based brand equity and are defined in this section.

The external audiences’ brand information processing creates important outputs, brand-related judgments and feelings (Keller 2001, 2016). Brand-controlled interactions are experiences developing subjective esoteric impressions in consumers’ minds, varying in polarity and amplitude (Chevtchouk et al. 2021). Brand associations influence brand attitude (O’Cass and Grace 2004) and, depending on the situation, the same associations and benefits might lead some consumers to subjectively develop positive, and other consumers negative, brand attitude (Parmentier and Fischer 2015). Consumers’ clear and strong brand-related opinions, beliefs and feelings indicate cognitive and emotional engagement and high brand’s share of mind and strength (Veloutsou et al. 2020). When these clear and strong brand-related opinions, beliefs and feelings are positive, then brands also score high in key indicators of consumer-based brand equity (Veloutsou et al. 2013).

The rational evaluation of a brand’s meaning and benefits leading consumers to develop brand-related personal opinion, assessment or judgement (Keller 2001), is an element of the market brand mindset block labelled as “share of attitude”. Going over and above the specific brand characteristics, the brand assessment in the brand building and audience response chain is the cognitive expression on whether the characteristics are good or bad. Without providing an exhaustive list, consumers with a positive brand attitude find it comforting, favourable, trusted, relevant, respected, while consumers with a negative brand attitude characterise it as discomforting, unfavourable or distrusted. Other positive or negative assessments may also be relevant, depending on the situation.

The audiences’ emotional reaction derives from two elements of the brand meaning block: “brand feelings” and “brand relationships”. The breadth and depth of understanding of the brand characteristics, as informed from the brand interactions (Albert and Thomson 2018), influence the development of brand-related feelings and relationships (Chatzipanagiotou et al. 2016; Veloutsou et al. 2020), increasing the brand’s impact of breadth and making it relevant to the interpersonal self (Bagozzi et al. 2021). Research has long appreciated that brands serve as relationship builders (de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 2000), an important advance for brand consumers (O’Cass and Grace 2004), and brands’ functional and symbolic values contribute to long-lasting consumer-brand relationship development (Merz et al. 2009). A lot of this argumentation builds on the idea that consumers see brands as humans (brand anthropomorphism), acknowledging that consumers develop feelings towards (share of sensation) and relationships with (share of heart) brands with varying polarity (Albert and Thomson 2018; Fetscherin et al. 2019). Positive brand feelings could be comfort, attachment, commitment, attitudinal loyalty or harmony, while negative brand feelings comprise discomfort, detachment, attitudinal disloyalty or anger. The overall brand relationship is characterised from the level of passion and the feeling of brand polarity (Fetscherin et al. 2019). A positive brand relationship can take the form of brand like or love, while a negative brand relationship can comprise brand dislike or hate.

The market brand mindset (brand assessment, brand feelings and brand relationships) evolves and adjusts as the market brand meaning changes. For example, recent research examining the nature of consumers’ brand relationships acknowledges that, as with relationships between humans, relationships between consumers and brands change in their nature over time (Veloutsou et al. 2020).

Market action

The final chain building block is market action. External audiences intended or actual investment of time, energy, money or other resources into the brand before, during or after the brand purchase or consumption (Keller 2001), are important for strong brands’ (Veloutsou et al. 2020) and behavioural engagement (Dessart et al. 2015). Recent literature extends earlier approaches reporting the need to identify what consumers do about the brand (Keller and Lehmann 2006), classifying market action as intended or actual, with polarity, and broadly taking one of three forms, namely: say, choose and devote (Fetscherin et al. 2021)—the classification of elements also used in the market action block and often approached as aspects of brand strength and behavioural consumer-based brand equity.

The first behaviour element details what the audience wants to communicate, the share of voice. External audiences can vocally express their brand-related views in private or public. Brand-related views can be positive, such as feedback, positive word-of-mouth (WoM), brand evangelism, advocacy, defence, or negative, such as complaining or negative WoM. There is a clear indication that research in services engages a lot with what consumers say, since the term service features in five of the 11 clusters identified in a systematic review of the literature on WoM, while a great proportion of papers on eWoM can be identified in services academic journals (Donthu et al. 2021).

Most firms aspire to achieve the second action element, which is securing brand choice and transaction. Much research focuses on loyalty in terms of repeat purchase, with academics agreeing that repeat purchase is a key brand objective (Keller 2001). Brand associations and attitude influence brand use intention (O’Cass and Grace 2004), while there is plenty of evidence over the years that brand relationships lead to brand loyalty (Khamitov et al. 2019). The transactional element has polarity and, when positive, includes behaviours such as brand preference, brand loyalty, purchase and usage; meanwhile, when negative, behaviours comprise brand avoidance, boycotting and brand switching.

The final action element demonstrates devotion, or the degree that audiences are prepared to demonstrate over and above communication and purchase/use brand reactions. Branding provides a symbolic language through which people can express themselves, build their self-identity and express who they are to others through a series of exchanges. Consumers do not consume brands in one single transactional exchange and consumption, they engage with brands as individuals, and as parts of groups (Dessart et al. 2015). Brands give a sense of community (Keller 2001), act as socialising agents contributing to developing relationships between consumers, who form groups to share their shared brand passion (Veloutsou and Liao 2022; Veloutsou and Ruiz-Mafé 2020) sometimes supporting brand development and delivery (Cova et al. 2015; Black & Veloutsou 2017) and others going against the brand’s views and values (Dessart et al. 2020; Dessart and Cova 2021). In that respect, brands with high impact of breadth are relevant to the consumers’ group self (Bagozzi et al. 2021). Positive reactions could be the willingness to engage with brand co-creation, to sacrifice, or to join brand communities, while negative reactions include brand sabotage and joining anti-brand communities.

The Influencing factors–moderators of the brand activation chain

As in previous conceptual frameworks presenting brand-related chains that lead to brand value that introduce multipliers/filters that moderate the movement from one stage to another (Keller and Lehmann 2003), specific influencing factors that manipulate the activation from the one part of the chain to another are suggested as the second main component of the framework. These influencing factors are introduced between the brand building and audience response chain building blocks and facilitate brands to increase their impact of breadth to consumers (Bagozzi et al. 2021).

The first influencing factor labelled “Attention: Offer & Campaign” is between the internal brand and market brand meaning (Fig. 2) and aims to identify elements that can help brands appeal to the personal self and attain a position as a passive object with utilitarian and symbolic meaning (Bagozzi et al. 2021). To start the brand knowledge-building, external audiences should be reached, and the transmitted brand signals through the offer and all brand experiences should attract their attention and interest. To position the brand in consumers’ minds (Blankson and Kalafatis 1999), the encoded, transmitted to and received from external audiences’ brand-related messages develop impressions related to each isolated experience (brand image) and also update the overall, accumulated brand view/associations/knowledge (brand reputation). Developing a clear brand identity (internal brand meaning) and making sure that this identity is realised, appreciated and supported from the internal market (employees) is key to secure internal and external brand meaning consistency (de Chernatony and Segal-Horn 2001). Brand support systems, assuring that employees are trained and able to design and project focused, clear, consistent (de Chernatony and Segal-Horn 2003; Chung and Byrom 2021), credible, reliable (Aaker 1996; Albert and Thomson 2018) and distinctive/unique (Keller1993) brand signals in all brand touchpoints, will help the activation of the market brand meaning block.

The second influencing factor labelled “Processing: Sensing” is between the market brand meaning and the market brand mindset (Fig. 2) and facilitates brands to increase their breadth of impact and become relevant to the audience’s interpersonal self (Bagozzi et al. 2021). New brand information and existing brand knowledge are processed and initially sensed. Brands that add value are promoting well-being and allow individuals to express who they are (Swaminathan et al. 2020), increasing their willingness to develop more self-relevant relationships with these brands (Albert and Thomson 2018), an aspect long appreciated as important in the services literature (Cass and Grace 2004). The meaningfulness of the brand reputation attributes (or brand knowledge) to consumers and the degree that they appreciate these characteristics also contribute to the brand’s assessment (Keller 2016). Brands’ consumers obtain functional, symbolic and experiential value that the perceived brand characteristics secure (Merz et al. 2009). The functional brand value, demonstrated through recognisability, and the symbolic value offered via the provision of meanings, identity and certain status, contribute to the development of brand assessments, feelings and relationships. More involved customers are more likely to process the brand information (Keller and Lehmann 2006), and the same will be the case for customers who see the brand information as more relevant and congruent with their existing views, or customers who had a positive brand experience.

The final influencing factor labelled “Processing: Reflection” is between the market brand mindset (Fig. 2) and intended and real market action, which will permit brands to reach the highest impact of breadth by becoming creators of social identity and group-linking value relevant to the audience’s group self (Bagozzi et al. 2021). The formed brand assessment, feelings and relationships are processed and a deeper reflection inspires further action, especially for highly involved individuals. Consumers benchmark themselves with the specific assessment of the brand characteristics looking for congruence and self-expression to act positively (Albert and Thomson 2018). To act, they also need to have the required resources, such as time, money and knowledge, and the need to act.

The feedback loops

In accordance with signalling theory (Connelly et al. 2011), brand information (brand building signals) may be transmitted over time by many different parties, and not just the company. The brand building and audience response framework incorporates the messages from other than the company actors as its final main component, named the feedback loops. Feedback loops can originate from the market brand mindset and the market action and feed both internal and market brand mindset, sending signals from entities that were initially acted as receivers to parties that originally being senders (see arrows in the bottom of Fig. 2).

The first feedback loop portrays esoteric brand-related processes that are very individual to each individual and their personal connection with a specific brand. This spontaneous loop starts from the market brand mindset and feeds back to the market brand meaning. Brand information and facts are processed rationally and emotionally. The outcome of brand assessment informs and updates the perceptions of the original information and facts. This circular private and self-directed process, used for self-guidance and self-regulation, implies that the formed rational judgments, feelings and relationships are used to update the utilitarian and symbolic brand meaning in this individual’s mind—the personal self (Bagozzi et al. 2021).

The second set of feedback loops starts from the market action to arrive at all the previous brand building and audience response chain blocks, from behaviour to mindset and meaning. Empowered customers are contributing to the development of brand meaning and inform the brand perceptions of the company, themselves and other consumers. The internal brand promise and core values (brand purpose and brand identity) are continuously adjusting incrementally (Abratt and Mingione 2017) informed from the views of customer and non-customer stakeholders (Iglesias and Ind 2020; Iglesias et al. 2020, 2023; Lückenbach et al. 2022; Urde 2013) as expressed from what they say, buy/use and their other brand reactions. Bringing information from the group self to the personal self (Bagozzi et al. 2021), brand-related behaviour is expected to infuse brand perceptions and assessment of the individual engaged in this behaviour but also the perceptions and assessments of other individuals who become aware of the actions.

The reverse to the brand building and audience response chain course implies brand co-creation (Cova et al. 2015; Black and Veloutsou 2017; Siano et al. 2022a) in all loops and in elements in the marketers’ sphere, stakeholders’ sphere or joined sphere as a locus (Christodoulides and Wiedmann 2022; Sarasvuo et al. 2022), function inflated from the technological developments facilitating consumers’ interactions (Asmussen et al. 2013; Dessart and Cova 2021; Oh et al. 2020; Swaminathan et al. 2020; Veloutsou and Liao 2022; Veloutsou and Ruiz-Mafé 2020). Brand meaning, from identity to reputation, is co-created from heterogeneous actors who through ongoing exchanges and practices collectively constantly redefine the brand (Padela et al. 2023; Price and Coulter 2019). The importance of brand co-creation can be fundamental, since research reports that brands perceived as unable to be influenced may experience decreased purchase intention from some consumer segments (Kennedy and Guzmán 2017; Kennedy et al. 2022). The brand meaning co-creation though can move to the extreme where its final form is not totally in line with the original producer-intended meaning (Parmentier and Fischer 2015) and be either re-positioned to meet external audiences’ expectations (Bhargava and Bedi 2021) or suffer reputation damage (Siano et al. 2022b). To safeguard brand adjustment to changes in the environment and continue to bring value to consumers, firms must understand how consumer behaviours affects their employees’ job performance, satisfaction, overall well-being and it may influence the internal understanding of the brand and lead to brand identity or controlled brand signalling modifications (Ostrom et al. 2015).

Concluding remarks

Discussion and theoretical implications

The synthesis of existing information on brand meaning development and management in a way that contributes new knowledge to the profession provides evidence, suggesting that research and practice might be undermining the strategic importance of brands. There are also indications that the literature in some research areas neglects branding. For example, work on services research priorities or insights either hardly mentions the term brand (Ostrom et al. 2015) or, when it does, presents it combined with selling (Ostrom et al. 2010). These indications accelerate the need to deeply comprehend branding and its consequences in all sectors.

Reconciling and extending past research (Cropanzano 2009; Palmatier et al. 2018; Snyder 2019), this work presents the brand building and audience response framework, aiming to explain how the firm’s brand building activities and external signalling activate audiences’ cognitive and emotional processing and activate diverse behavioural brand engagement. Following common practice (Rumrill and Fitzgerald 2001), the introduced framework advances existing knowledge and consists of three specific components. The first framework component—brand building and audience response chain—comprises four building blocks that, through their functions and components, elucidate the link between the firm’s brand-related decisions (internal brand meaning) signalling through strategies and tactics and audience-processing, that generate cognitive, emotional and behavioural responses (market brand meaning, market brand mindset and market action). The second framework component—the influencing factors that moderate/activate the transfer between the chain blocks—presents conditions facilitating or hindering the movement from one chain block to the next. The final framework component—the feedback loops—presents how later chain blocks may feed back into earlier blocks to fine-tune their content.

The proposed framework is more fully developed than previously reported work. It synthesises, updates and extends existing knowledge by broadening and improving existing services marketing and brand management frameworks on brand building and its consequences. The brand building and audience response framework introduces conditions manipulating the activation of the building blocks through the inclusion of influencing factors that exist between the block. Through the incorporated feedback loops, the framework also highlights the audience’s nonlinear information processing and engagement with internal and external brand meaning co-creation. The addition of both positive and negative audience responses in the framework is also a previously rarely acknowledged feature (Fetscherin et al. 2021; Veloutsou and Guzmán 2017).

The strength and direction of a brand’s impact on consumers over time is also enlightened through the brand building and audience response framework. The framework unfolds the process of moving from the level of being a passive object with utilitarian and symbolic meaning relevant to the personal self, to an active relationship partner relevant to the interpersonal self and, finally, becoming a creator of social identity with social linking power relevant to the group (Bagozzi et al. 2021). To illuminate brand performance’s richness, several indicators are needed, and existing research tries to incorporate many ideas presented in the brand building and audience response chain when capturing it (Lehmann et al. 2008). Existing research appreciates that consumer-based brand equity encompasses measures belonging to four categories of measures: consumers’ understanding of brand characteristics; consumers’ brand evaluation; consumers’ affective response towards the brand; and consumers’ behaviour towards the brand (Veloutsou et al. 2013). These consumer-based brand equity suggested categories of measures are similar to the blocks incorporated in the brand building and audience response chain, but the latter varies in polarity. Strong positive or negative responses demonstrate that brands are strong, but strong positive responses are synonymous with high consumer-based brand equity (Chatzipanagiotou et al. 2016). Brands that encounter negative responses are looking at signalling tactics to reverse negative to positive valence of response (Veloutsou et al. 2020).

Existing signalling research on brand-related outcomes seems to primarily examine behavioural outcomes, principally behavioural loyalty, repurchase or WoM, but the real responses are far more diverse in nature (Khan et al. 2019). Market signalling is unlikely to directly lead to audience responses without processing and existing research engagement does not help practitioners seeking to understand how their activities affect audience responses. To support practitioners to develop and implement well-focused and effective branding strategies, research should further explore the blocks of the chain and their element, rather than concentrating almost exclusively on behavioural outcomes. Alternative cognitions, emotions and behaviours that are increasingly visible in practice should be incorporated in the wider research, rather than reproducing variations of what we know and providing marginal value by adding some moderators or mediators in existing research frameworks.

Coordinating the interdependent roles of employees, customers and other parties in the brand meaning co-creation is, and will remain, a key concern for complex brands, such as services (Ostrom et al. 2015), and for branding research. It would be useful for future research to extend existing approaches that primarily focus on a very small number of constructs and identify chain block components and choose or develop measures to capture them that are appropriate for and tailored to specific contexts and brands.

Practical implications

Past research highlights that organisations often give insufficient attention to brand building, even for complex offerings such as services (de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 1999). Brands are strategic tools (Swaminathan et al. 2020) and the expected effects of firms’ choices on brand meaning should rule all decision-making and dictate all actions. The brand building and audience response framework aims to help practising managers appreciate holistically the way that their companies’ branded offers are perceived from various audiences and allow them to build brands that can trigger audiences’ active behaviour.

Brands can be very complex and often require very demanding brand building efforts. Designing and supporting the brand is crucial for enhancing consumers’ perceptions and growing strong and positive reputations for all brands (de Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 2000). Given that intended, actual and perceived brand meaning (brand positioning) may have differences (Fuchs and Diamantopoulos 2010), a good management of the brand building process can help in the reduction of deviations and secure more consistent brand meaning perceptions between the various parties involved in the process. Various company initiated signalling actions can contribute to the reduction of any deviations on brand perceptions.

The brand building and audience response framework can also help managers better appreciate that strong brands are developed through a process and brand signalling and actions do not automatically translate to intended or actual audiences’ market action. Strong brands are not any different, but they have audiences possessing deep brand knowledge that is assessed and produce brand feelings and brand relationships. Brand signals can initiate market action, but the outcome will come as a chain reaction and influenced by many moderating factors. Aiming to produce market action results as an outcome of signalling without considering the in-between parts of the process could be elusive. Fully understanding the complexity of the process can help practising managers to set better objectives for signalling campaigns, such as marketing communications, that incorporate audiences’ knowledge-building and attitude, feeling and relationship development as objectives.

Recent developments have increased the brand building process complexity for companies. Brand meaning co-creation raises questions concerning who really is in charge of creating and maintaining the brand meaning (Cova and Paranque 2016; Veloutsou 2022). In an increasingly technology-facilitated delivery process, services might be dehumanising and have fewer front-end employees involved (Ostrom et al. 2015) and provide new ways of interaction, aspects visible in all industries but even so in many services sectors. Brand purpose and brand identity development and brand meaning management in external audiences’ minds remain, and should always be, the priority for practising managers. Securing that the trends in ways that brands are developed and audiences interact with them are fully appreciated by the companies producing the offers, can help these companies better manage the brand building process and secure more desirable returns.

Brands aim to stay away from indifference and develop strong positive and negative valanced assessment, feelings, relationships and reactions (Fetscherin et al. 2019). They may experience positive and negative consumer disposition from different consumer groups, a situation that could be intentional and with benefits for the brands (Osuna-Ramírez et al. 2019). There are also cases where external brand meaning and audience reaction divert from internally intended brand meaning (Parmentier and Fischer 2015) in a direction unwanted by the firm. Unfolding the process of nurturing strong responses when wanted, such by supporting brand positioning (Osuna-Ramírez et al. 2019), or avoid unwanted negative responses, such after a service failure (Chen et al. 2018; Khamitov et al. 2020), and identifying specific tactics that can generate the audiences’ desired reactions, provides useful insights for practising managers and new avenues for academic research. The brand building and audience response framework elucidates that brand signalling and audience behaviour are rarely directly related, which helps in the identification of relevant cognitive and emotional aspects that, when considered, illuminate the process and influence the desired outcome.

Limitations and directions for future research

What the brand building and audience response framework does not fully capture or report, is the contribution of uncontrollable signals originating from multiple, actively involved, parties other than the main targeted brand audiences on brand meaning creation (Buhalis and Park 2021; Vallaster and von Wallpach 2013; Veloutsou 2022). Potentially involved stakeholders not fully accounted for may include competitors, third parties such as the press, independent reviews or distribution channels, or other uncontrolled entities such as co-brands, the industry or the country of origin (Keller and Lehmann 2006; Vallaster and von Wallpach 2013; Veloutsou 2022; Veloutsou and Delgado-Ballester 2018), or even the broader society (Price and Coulter 2019; Swaminathan et al. 2020). The signals from these sources, who can still be seen as audiences that the framework considers, will influence all brand building chain blocks. Future research should expand our knowledge on the role of particular actors in the brand building process. The interactions between these actors and their relative power in brand building also need further investigation.

As all integrative literature reviews, the proposed framework and its suggested components reflect the intuition and research experience of the researchers engaged in this project. However, in a piece focusing on a broad core domain and incorporating relevant trends to enlighten it, like this paper, adopting a more systematic approach is an unrealistic option.

Researchers can benefit from the brand building and audience response framework when designing their research projects. The complexity of the brand building process, the specific order that brand building–audience response chain building blocks work (market brand meaning, market mindset and intended and actual behaviour), the influential factors between the building blocks moderating the process and feedback loops facilitating brand co-creation should be factored in future research. The differences in the nature of the various brand meaning related terms (brand purpose, brand identity, brand image and brand reputation) and the interrelation of these terms needs to be also acknowledged in research project design. Attempts to validate small parts of the framework by incorporating them in research models are a good avenue for future work for micro, meso or macro theory level—depending on the project’s specific focus. It is possible that some work may try to incorporate larger parts of the framework in a project, but this engagement will require a close look at methodologies that can overcome the difficulties imposed by the need to collect data from many actors in more than one point in time for such type of project and the fact that the relationships between the constructs in the framework are dynamic and complex.

Change history

19 October 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-023-00345-6

References

Aaker, D. 1996. Building strong brands. Free Press.

Abratt, R., and M. Mingione. 2017. Corporate identity, strategy and change. Journal of Brand Management 24 (2): 129139.

Albert, N., and M. Thomson. 2018. A synthesis of the consumer-brand relationship domain: Using text mining to track research streams, describe their emotional associations, and identify future research priorities. Journal of the Association of Consumer Research 3 (2): 130–146.

Asmussen, B., S. Harridge-March, N. Occhiocupo, and J. Farquhar. 2013. The multi-layered nature of the internet-based democratization of brand management. Journal of Business Research 66 (9): 1473–1483.

Bagozzi, R.P., S. Romani, S. Grappi, and L. Zarantonello. 2021. Psychological underpinnings of brands. Annual Review of Psychology 72: 585–607.

Balmer, J.M.T., and K. Podnar. 2021. Corporate brand orientation: Identity, internal images, and corporate identification matters. Journal of Business Research 134: 729–737.

Baron, S., G. Warnaby, and P. Hunter-Jones. 2014. Service(s) marketing research: Developments and directions. International Journal of Management Reviews 16: 150–171.

Bergkvist, L., and C.R. Taylor. 2016. Leveraged marketing communications: A framework for explaining the effects of secondary brand associations. AMS Review 6 (3/4): 157–175.

Berry, L.L. 2000. Cultivating service brand equity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 28 (1): 128–137.

Black, I., and C. Veloutsou. 2017. Working consumers: Co-creation of brand identity, consumer identity and brand community identity. Journal of Business Research 70: 416–429.

Blankson, C., and S.P. Kalafatis. 1999. Issues and challenges in the positioning of service brands: A review. Journal of Product & Brand Management 8 (2): 106–118.

Blankson, C., and S.P. Kalafatis. 2007. Positioning strategies of international and multicultural-oriented service brands. Journal of Services Marketing 21 (6): 435–450.

Boyle, E. 2007. A process model of brand cocreation: Brand management and research implications. Journal of Product & Brand Management 16 (2): 122–213.

Brown, T.J., P.A. Dacin, M.G. Pratt, and D.A. Whetten. 2006. Identity, intended image, construed image and reputation: An interdisciplinary framework and suggested terminology. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34: 99–106.

Buhalis, D., and S. Park. 2021. Brand management and cocreation-lessons from tourism and hospitality: Editorial. Journal of Product & Brand Management 30 (1): 1–11.

Chatzipanagiotou, K., C. Veloutsou, and G. Christodoulides. 2016. Decoding the complexity of the consumer-based brand equity process. Journal of Business Research 69 (11): 5479–5486.

Chen, T., K. Ma, X. Bian, C. Zheng, and J. Devlin. 2018. Is high recovery more effective than expected recovery in addressing service failure? A moral judgment perspective. Journal of Business Research 82: 1–9.

Chevtchouk, Y., C. Veloutsou, and R. Paton. 2021. The experience economy revisited: An interdisciplinary perspective and research agenda. Journal of Product & Brand Management 30 (8): 1288–1324.

Christodoulides, G., and K.P. Wiedmann. 2022. Guest editorial: A roadmap and future research agenda for luxury marketing and branding research. Journal of Product & Brand Management 31 (3): 341–350.

Chung, S.-Y., and J. Byrom. 2021. Co-creating consistent brand identity with employees in the hotel industry. Journal of Product & Brand Management 30 (1): 74–89.

Coleman, D., L. de Chernatony, and G. Christodoulides. 2011. B2B service brand identity: Scale development and validation. Industrial Marketing Management 40 (7): 1063–1071.

Conejo, F., and B. Wooliscroft. 2015. Brands defined as semiotic marketing systems. Journal of Macromarketing 35 (3): 287–301.

Connelly, B.L., S.T. Certo, R.D. Ireland, and C.R. Reutzel. 2011. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. Journal of Management 37 (1): 39–67.

Cova, B., and B. Paranque. 2016. Value slippage in brand transformation: A conceptualization. Journal of Product & Brand Management 25 (1): 3–10.

Cova, B., S. Pace, and P. Skålén. 2015. Brand volunteering: Value co-creation with unpaid consumers. Marketing Theory 15 (4): 465–485.

Cropanzano, R. 2009. Writing nonempirical articles for Journal of Management: General thoughts and suggestions. Journal of Management 35 (6): 1304–1311.

de Chernatony, L. 1999. Brand management through narrowing the gap between brand identity and brand reputation. Journal of Marketing Management 15: 157–179.

de Chernatony, L., and Dall’Olmo Riley, F. 1999. Experts’ views about defining services brands and the principles of services branding. Journal of Business Research 46: 181–192.

de Chernatony, L., and Dall’Olmo Riley, F. 2000. The service brand as relationships builders. British Journal of Management 11: 137–150.

de Chernatony, L., and S. Segal-Horn. 2001. Building on service’s characteristics to develop successful services brands. Journal of Marketing Management 17 (7–8): 645–669.

de Chernatony, L., and S. Segal-Horn. 2003. The criteria for successful services brands. European Journal of Marketing 37 (7/8): 1095–1118.

Dekkers, R., L. Carey, and P. Langhorne. 2022. Making literature reviews work: A multidisciplinary guide to systematic approaches. London: Springer.

Dessart, L., C. Veloutsou, and A. Morgan-Thomas. 2015. Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A social media perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management 24 (1): 28–42.

Dessart, L., C. Veloutsou, and A. Morgan-Thomas. 2020. Brand negativity: A relational perspective on anti-brand community participation. European Journal of Marketing 54 (7): 1761–1785.

Dessart, L., and B. Cova. 2021. Brand repulsion: Consumers’ boundary work with rejected brands. European Journal of Marketing 55 (4): 1285–1311.

Donthu, D., S. Kumar, N. Pandey, N. Pandey, and A. Mishra. 2021. Mapping the electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) research: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Journal of Business Research 135: 758–773.

Dowling, G.R. 2016. Defining and measuring corporate reputations. European Management Review 13 (3): 207–223.

Ferreira, J.J.M., C.I. Fernandes, and V. Ratten. 2016. A co-citation bibliometric analysis of strategic management research. Scientometrics 109 (1): 1–32.

Fetscherin, M., C. Veloutsou, and F. Guzmán. 2021. Models for brand relationships: Guest editorial. Journal of Product & Brand Management 30 (3): 353–359.

Fetscherin, M., F. Guzmán, C. Veloutsou, and R.R. Cayolla. 2019. Latest research on brand relationships: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Product & Brand Management 28 (2): 133–139.

Fuchs, C., and A. Diamantopoulos. 2010. Evaluating the effectiveness of brand-positioning strategies from a consumer perspective. European Journal of Marketing 44 (11/12): 1763–1786.

Gaski, J.F. 2020. A history of brand misdefinition–with corresponding implications for mismeasurement and incoherent brand theory. Journal of Product & Brand Management 29 (4): 517–530.

Guzmán, F., J. Montaña, and V. Sierra. 2006. Brand building by associating to public services: A reference group influence model. Journal of Brand Management 13: 353–362.

Highhouse, S., A. Broadfoot, J.E. Yugo, and S.A. Devendorf. 2009. Examining corporate reputation judgments with generalizability theory. Journal of Applied Psychology 94: 782–789.

Huang, M.-H., and C. Dev. 2020. Growing the service brand. International Journal of Research in Marketing 37 (2): 281–300.

Hulland, J., and M.B. Houston. 2020. Why systematic review papers and meta-analyses matter: An introduction to the special issue on generalizations in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 48: 351–359.

Iglesias, O., and N. Ind. 2020. Towards a theory on conscientious corporate brand cocreation: The next key challenge in brand management. Journal of Brand Management 6 (27): 710–720.

Iglesias, O., P. Landgraf, N. Ind, S. Markovic, and N. Koporcic. 2020. Corporate brand identity co-creation in business-to-business contexts. Industrial Marketing Management 85: 32–43.

Iglesias, O., M. Mingione, N. Ind, and S. Markovic. 2023. How to build a conscientious corporate brand together with business partners: A case study of Unilever. Industrial Marketing Management 109: 1–13.

Jaakkola, E., A. Helkkula, and L. Aarikka-Stenroos. 2015. Service experience co-creation: Conceptualization, implications, and future research directions. Journal of Service Management 26 (2): 182–205.

Jaakkola, E. 2020. Designing conceptual articles: Four approaches. AMS Review 10 (1): 18–26.

Jabareen, Y. 2009. Building a conceptual framework: Philosophy, definitions, and procedure. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8: 49–62.

Kabadayi, S., F. Ali, H. Choi, H. Joosten, and C. Lu. 2019. Smart service experience in hospitality and tourism services: A conceptualization and future research agenda. Journal of Service Management 30 (3): 326–348.

Kapitan, S., J.A. Kemper, J. Vredenburg, and A. Spry. 2022. Strategic B2B brand activism: Building conscientious purpose for social impact. Industrial Marketing Management 107: 14–28.

Keller, K.L. 1993. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing 57 (1): 1–22.

Keller, K.L. 2001. Building customer-based brand equity: A blueprint for creating strong brands. Marketing Management 10 (2): 15–19.

Keller, K.L. 2003. Brand synthesis: The multi-dimensionality of brand knowledge. Journal of Consumer Research 29 (4): 595–600.

Keller, K.L. 2016. Reflections on customer-based brand equity: Perspectives, progress, and priorities. Academy of Marketing Science Review 6 (1): 1–16.

Keller, K.L. 2023. Looking forward, looking back: Developing a narrative of the past, present and future of a brand. Journal of Brand Management 30: 1–8.

Keller, K.L., and D. Lehmann. 2003. How do brands create value. Marketing Management 3: 27–31.

Keller, K.L., and D. Lehmann. 2006. Brands and branding: Research findings and future priorities. Marketing Science 25 (6): 740–759.

Kennedy, E., and F. Guzmán. 2017. When perceived ability to influence plays a role: Brand co-creation in Web 2.0. Journal of Product & Brand Management 26 (4): 342–350.

Kennedy, E., F. Guzmán, and N. Ind. 2022. Motivating gender toward co-creation: A study on hedonic activities, social importance, and personal values. Journal of Brand Management 29 (1): 127–140.

Khamitov, M., Y. Grégoire, and A. Suri. 2020. A systematic review of brand transgression, service failure recovery and product-harm crisis: Integration and guiding insights. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 48 (3): 519–542.

Khan, M. A., C. Veloutsou, & K. Chatzipanagiotou, 2019. Consequences towards brands after a service failure: a holistic view. 14th Global Brand Conference Proceedings, 8–10 May, Berlin, Germany.

Khamitov, M., X. Wang, and M. Thomson. 2019. How well do consumer-brand relationships drive customer brand loyalty? Generalizations from a meta-analysis of brand relationship elasticities. Journal of Consumer Research 46: 435–459.

Kraus, S., M. Breier, W.M. Lim, M. Dabić, S. Kumar, D. Kanbach, D. Mukherjee, V. Corvello, J. Piñeiro-Chousa, E. Liguori, C. Fernandes, J.J. Ferreira, D.P. Marqués, F. Schiavone, and A. Ferraris. 2022. Literature reviews as independent studies: Guidelines for academic practice. Review of Managerial Science 16: 2577–2595.

Kotler, P. 2003. Marketing Management, 11th International Edition, Pearson Education.