Abstract

The hybrid utilization of SiC and Si devices can achieve a trade-off between the efficiency and cost of three-level active neutral-point-clamped (3L-ANPC) inverters. This paper studies a three-phase 2-SiC 3L-hybrid ANPC (3L-HANPC) inverter with different discontinuous pulse width modulation (DPWM) schemes. The principles of these DPWM schemes are analyzed in detail, and carrier-based algorithm for two of the DPWM schemes are given. Finally, a 6 kW three-phase 2-SiC 3L-HANPC inverter prototype was built to compare these two modulation schemes. Experimental results show that DPWM1 with its peak voltage-clamped can achieve a higher efficiency than DPWM2 with its zero-crossing clamped. However, the DPWM2 scheme has a lower THD than the DPWM1 scheme. Since the THD improvement contributed by the DPWM2 scheme is relatively small, the DPWM1 scheme is the preferred DPWM scheme.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Compared with Si semiconductor materials, wide bandgap (WBG) semiconductor materials represented by silicon carbide (SiC) have a higher breakdown voltage, better thermal stability, higher saturation drift velocity of the carrier, and higher thermal conductivity [1]. Therefore, SiC devices can operate with a higher switching frequency and a higher efficiency [2, 3]. As a result, SiC devices have attracted a great deal of attention in emerging industries such as electric vehicle (EV) chargers and energy storage systems. However, in high-capacity applications, such as motor drivers and photovoltaic (PV) inverters, SiC devices are too expensive to be widely used, while traditional Si IGBT devices are still the mainstream [4]. Therefore, converters with a combination of SiC and Si devices are cost-effective [5, 6].

A performance comparison of a Si-based soft-switching inverter and a SiC-based hard switching inverter was presented in [7]. Results showed that at a high switching frequency, the cost of the SiC-based inverter was 60% lower than that of the soft-switching inverter, while higher efficiency was achieved. In [8], a Si/SiC hybrid converter was designed to drive a high-speed motor. Based on the hybrid utilization of Si and SiC devices, a high switching frequency, small overall power loss, and output current ripple were realized at a low cost. In [9], a three-phase Si/SiC three-level hybrid active neutral-point-clamped (3L-HANPC) converter for medium voltage high-speed drive systems was proposed, and a corresponding optimized space vector pulse width modulation (SVPWM) was presented. While the voltage balance of the upper and lower capacitors on the DC side was ensured, the switching loss was concentrated in the SiC MOSFETs to realize a high efficiency and low cost.

However, when WBG devices are applied to enhance the switching frequency and power density, the switching loss inevitably increases. Thus, discontinuous pulse width modulation (DPWM) instead of continuous pulse width modulation (CPWM) is a better solution for converters with a high switching frequency [10,11,12,13,14,15]. In addition, considering that a high switching frequency reduces the interrupt cycle of digital control, the calculation of DPWM based on the space vector synthesis method is complicated [13]. Thus, DPWM modulation based on the carrier-based method has been used to lower the calculation burden of digital processors [16, 17]. A DPWM scheme for use in a grid-tied three-level neutral point-clamped (3L-NPC) converter was presented in [14]. In this way, the targets of reducing losses and increasing efficiency were realized. The DPWM scheme applied to a three-level (3L) inverter was optimized in [18]. In addition, the peak clamped DPWM and the carrier-based zero-crossing clamped DPWM methods were presented.

To date, there have been many comparative evaluations of Si/SiC hybrid inverters based on SVPWM schemes. However, the comparative analysis of DPWM schemes, especially for three-phase Si/SiC 3L-HANPC converters, still needs to be explored. Therefore, based on the three-phase Si/SiC 3L-HANPC inverter, two DPWM schemes, peak clamped DPWM and zero-crossing clamped DPWM, are compared with respect to efficiency and total harmonic distortion.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. First, the topology of a 3L-ANPC inverter with the combination of Si IGBTs and SiC MOSFETs is presented, and the conventional SVPWM scheme is introduced. The principle of peak clamped DPWM and zero-crossing clamped DPWM is discussed. Then, a power loss model is built to theoretically evaluate the efficiency performance of these two DPWM schemes. Then, a THD performance comparison is conducted by simulation. In Sect. 4, an experimental comparison of the efficiency and THD performance is demonstrated. Finally, Sect. 5 concludes the paper.

2 Three-phase Si/SiC 3L-HANPC inverter

2.1 Three-phase 2-SiC 3L-HANPC inverter topology

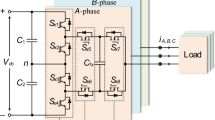

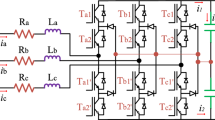

The ANPC converter is the only three-level topology that can decouple circuits into high-frequency and low-frequency parts, which easily implements the hybrid application of SiC MOSFETs [9]. Thus, the SiC MOSFETs operate at high frequency and have the switching loss centrally, while the Si IGBTs operate at the fundamental frequency, which reduces the cost while keeping the efficiency comparable to that of the full SiC inverter [19,20,21]. The topology of the three-phase 2-SiC 3L-HANPC inverter proposed in [9] is depicted in Fig. 1. The two switches Sx5 and Sx6 (x = a, b, c) of each phase are replaced with SiC MOSFETs as high switching frequency switches. They act complementarily at high switching frequencies, marked as dark yellow. The rest of the devices are Si IGBTs.

There are four switching states by employing the SVPWM scheme for an ANPC inverter, as given in Table 1. In this table, 1 and 0 represent the ON and OFF states of the switches, respectively. Phase A is taken as an example to clearly illustrate the switching states. The commutation process of the switching states during the positive half cycle is depicted in Fig. 2.

2.2 Principle of the SVPWM Scheme

There are 64 three-phase switching states in the SVPWM scheme of this hybrid inverter. They are generated by combining the above four switching states “P,” “U,” “L,” and “N.” The distribution of the corresponding voltage vectors in the three-level vector space is shown in Fig. 3, where “O” stands for “U” or “L.” These voltage vectors are distributed in six large sectors from I to VI, and each of the large sectors can be divided into six small regions from 1 to 6.

According to Fig. 3, taking the reference voltage vector Vref located in sector I regions 3 as an example for analysis, the switching states process can be obtained based on the principle of “nearest three vectors” (NTV), as shown in Fig. 4. It is clear that the modulating signals are never clamped during the switching cycle in the conventional SVPWM.

3 Principle of the peak clamped DPWM and zero-crossing clamped DPWM schemes

In SVPWM, the bridge-leg voltage level of each phase is varied in every switching cycle, and the switching loss increases with the increase in the switching frequency. By discarding the redundant vector, DPWM clamps the bridge-leg voltage of one phase in a switching cycle. As a result, the switching times for each of the switching cycles are reduced to 2/3 of the continuous modulation, which ultimately reduces the switching loss at high switching frequencies [18]. This section introduces two common DPWM schemes for three-phase inverters: peak clamped DPWM1 and zero-crossing clamped DPWM2.

3.1 Principle of the peak clamped DPWM1 scheme

The clamping mode of peak clamped DPWM1 is shown in Fig. 5. From this figure, it can be seen that the vector clamping area is mainly adjacent to the peak value of the output voltage.

Moreover, the DPWM scheme can be implemented by injecting a zero-sequence component into three-phase sinusoidal modulation waves. The referenced three-phase sinusoidal modulation waves are expressed as:

where fg is the fundamental frequency of the utility grid, and M represents the normalized modulation amplitude value, which also represents the modulation index, and is calculated as follows:

where Uac is the RMS value of the utility grid phase voltage, and Udc is the DC bus voltage.

The injected zero-sequence component can be acquired as follows:

where umax and umin are the maximum and minimum of the three-phase sinusoidal modulation wave at certain times.

The three-phase modulation wave uref_x (x = a, b, c) of DPWM1 can be obtained by injecting (3) into (1), which is expressed as:

Taking phase A as an example, modulation waves of DPWM1 and the injected zero-sequence component under different modulation indices are presented in Fig. 6. It is clearly shown that DPWM1 is always clamped near the peak area of the modulation wave, which corresponds to the clamping areas in Fig. 5.

The position of the reference vector Vref is shown in Fig. 5. Meanwhile, the modulation waves of DPWM1, the voltage level of the bridge leg, and the corresponding switching states in a single switching cycle are illustrated in Fig. 7. When the modulation signal is greater than 0, the bridge leg voltage level of the unclamped phase is changed between the “P” and “L” states. Meanwhile, that of the clamped phase is forced to the “P” state. When the modulation signal is less than 0, the bridge leg voltage level of the unclamped phase switches is changed between the “U” and “N” states, and that of the clamped phase is forced to the “N” state. As shown in Fig. 7, the voltage level of phase A is clamped to P at this time.

3.2 Principle of the zero-crossing clamped DPWM2 scheme

The clamping mode of the zero-crossing clamped DPWM2 is shown in Fig. 8. The vector clamping area is mainly adjacent to the zero-crossing point and peak point of the output voltage, which can improve the zero-crossing distortion.

The carrier-based implementation method of DPWM2 was presented in [14]. The zero-sequence component can be calculated as follows:

where umax, umin, and umid stand for the maximum, minimum, and intermediate values of a three-phase sinusoidal modulation wave at a certain time. The intermediate variable required for judgment uz1 can be calculated by (3).

Similarly, a three-phase modulation wave of DPWM2 can be calculated by substituting (5) into (1). When the modulation index is higher than 0.577, the modulation wave is clamped at the zero-crossing and peak points. However, when the modulation index is less than 0.577, the clamping area of the modulation wave is adjacent to the zero-crossing point.

Figure 9 illustrates modulation waves of DPWM2 and its injected zero-sequence component under different modulation indices for phase A. It corresponds to the clamping areas shown in Fig. 8. The relationships among the modulation wave of DPWM2, the voltage level of the bridge leg, and the corresponding switching states are demonstrated in Fig. 10. When the reference vector is located in sector I region 3, as shown in Fig. 8, it is clear that the voltage level of phase B is clamped to the “U” level.

3.3 Power loss and THD performance analyses

A power loss model was built to quantitatively analyze the efficiency performance of these two DPWM schemes [22, 23]. By employing the 3L-HANPC converter topology and the two DPWM schemes, the SiC MOSFETs operate at a high switching frequency, while the Si IGBTs operate at the fundamental switching frequency. Therefore, the switching loss of the Si IGBTs can be ignored. The conduction loss of IGBTs can be expressed as:

where VCE(on) is the ON-state voltage drop of the IGBT, and ID(i) represents the ON-state collector-emitter current in the i-th switching period. The total switching time Mf in a fundamental cycle can be obtained by (7), where fg and fs represent the fundamental frequency and the switching frequency, respectively.

A switching process model of a SiC MOSFET was built, as shown in Fig. 11, where UDS is the OFF-state drain-source voltage, and ID is the ON-state drain current. When the MOSFET is turned ON, the ON-state resistance between the drain and the source is RDS (on) [22]. At this time, the drain-source voltage is Uon. tir and tvr represent the rise times of the drain current and the drain-source voltage, respectively. tif and tvf are the fall times of the drain current and the drain-source voltage, respectively. td(on) represents the turn-ON delay time of the MOSFET. All of the above data can be extracted from the SiC MOSFET datasheet.

Taking one switching cycle as an example, the switching loss of the SiC MOSFETs is zero when the bridge-leg voltage is clamped. Otherwise, the switching loss of the SiC MOSFETs during the i-th switching cycle is calculated as follows:

where UDS(i) and ID(i) are the drain-source voltage in the OFF state of the MOSFET, and the drain current in the ON state during the i-th switching cycle. Therefore, the switching loss of the three-phase 2-SiC 3L-HANPC inverter can be expressed as:

The conduction power loss of the SiC MOSFETs can be expressed as:

where d represents the duty cycle, and Ts represents the switching period. The total power loss of the Si IGBTs and the SiC MOSFETs can be calculated as:

The power loss calculation results of a three-phase 2-SiC 3L-HANPC inverter with different loads and modulation indices while using the two DPWM schemes are depicted in Fig. 12. As can be seen, the power loss of the DPWM1 scheme is always less than that of the DPWM2 scheme. Thus, since the clamping areas of the DPWM1 scheme are near the peak of the AC voltage and that of the output current, it can reduce more switching loss than the DPWM2 scheme, which leads to higher efficiency.

Simulation waveform of the two DPWM schemes and the harmonic spectrums of uAn are presented in Fig. 13. The simulation conditions are consistent with the experimental conditions shown in Table 2. uAn represents the differential-mode voltage between terminal A and terminal n, as shown in Fig. 1. uref_A is the modulation signal. As shown in Fig. 13, since the DPWM1 scheme has more harmonics near the switching frequency, DPWM2 has better harmonic performance than DPWM1.

4 Comparison of two modulation schemes

For an experimental comparison of the two different DPWM schemes, a three-phase 2-SiC 3L-HANPC inverter prototype was built in the laboratory.

The parameters of the 3L-HANPC inverter prototype are listed in Table 2. A TMS320F28335 and an EPM570T100I5N are used as the digital controller of this prototype. A picture of the prototype is shown in Fig. 14,.

Steady-state waveforms of the phase A driving signals while employing DPWM1 and DPWM2 are given in Figs. 15 and 16, respectively. Where ugs1, ugs2, ugs5, and ugs6 represent the driving signals of Sa1, Sa2, Sa5, and Sa6, while the modulation index is 0.78. From Fig. 15, it is clear that the driving signal of DPWM1 is only clamped near the peak point of the AC voltage. The driving signal of DPWM2 is clamped at both the zero-crossing and peak points of the AC voltage, which is consistent with the analysis in Sect. 3. Steady-state line voltage waveforms of the 2-SiC 3L-HANPC inverter while using DPWM1 and DPWM2 are shown in Figs. 17 and 18, respectively. uab, ubc, and uca represent line voltages. The output power is 3 kW, and the DC bus voltage is 800 V. It can be seen that the quality of the output voltage is good.

Steady-state waveforms of DPWM1 and DPWM2 with 5 kW of output power are presented in Figs. 19 and 20, where uAB and uab represent the line voltage before and after filtering, respectively. uCO and ic are the bridge leg voltage and current of phase C. This indicates that DPWM1 generates a voltage jump near the zero-crossing point, while the voltage level is clamped at the zero-crossing point to improve the voltage quality under DPWM2. However, the clamping area near the peak point of DPWM2 is much smaller than that of DPWM1. Therefore, DPWM1 can reduce more switching loss than the DPWM2 scheme, which is consistent with the above analysis.

A WT-1800 power analyzer is used to measure the efficiencies and THDs of the two modulation schemes. The measured efficiencies are shown in Fig. 21. It can be found that the efficiency of DPWM1 is always higher than that of DPWM2. In addition, this advantage is more significant under low modulation index conditions. This is due to the fact that the clamping area of the DPWM1 scheme is near the peak value point of the output voltage and that of the output current. Furthermore, experimental results show that the peak efficiency of DPWM1 is about 98.9%, with M = 0.9.

The measured voltage THDs of the two schemes with different loads and modulation indices are shown in Fig. 22. From this figure, it can be found that the THD value of the DPWM2 scheme is lower than that of the DPWM1 scheme. Thus, although the DPWM2 scheme has a lower efficiency, its THD performance is better than that of the DPWM1 scheme.

According to the efficiency and THD comparison results, the THD value difference between the two DPWM schemes is relatively small. However, the efficiency of the DPWM1 scheme is higher than that of the DPWM2 scheme, especially with low modulation indices. Therefore, DPWM1 is the preferred DPWM scheme for 2-SiC 3L-HANPC inverters.

5 Conclusion

Based on a three-phase 2-SiC 3L-HANPC inverter prototype platform, a performance comparison between two common DPWM schemes for three-phase inverters: peak clamped DPWM1 and zero-crossing clamped DPWM2 was conducted. The analysis and experimental results show a number of things.

-

(1)

The DPWM1 scheme with its peak voltage clamped can achieve a higher efficiency than DPWM2 with its zero-crossing clamped when applied to the three-phase 2-SiC 3L-HANPC inverter.

-

(2)

However, the DPWM2 scheme has better THD performance than that of the DPWM1 scheme.

Since the THD improvement contributed by the DPWM2 scheme is relatively small, the DPWM1 scheme is a preferred solution for improving the efficiency of three-phase 2-SiC 3L-HANPC inverters.

References

Yuan, X., Laird, I., Walder, S.: Opportunities, challenges, and potential solutions in the application of fast-switching sic power devices and converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 36(4), 3925–3945 (2021)

Bo, Q., Wang, L.F., Zhang, Y.W.: A SiC MOSFET-based parallel multi-inverter inductive power transfer (IPT) system. J. Power Electron (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43236-022-00393-2

Wang, F., Ji, S.Q.: Benefits of high-voltage SiC-based power electronics in medium-voltage power-distribution grids. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 7(1), 1–26 (2021)

Song, X.Q., Zhang, L.Q., Huang, A.Q.: Three-terminal Si/SiC hybrid switch. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 35(9), 8867–8871 (2020)

Liu, C., Zhuang, K.H., Pei, Z.C., Zhu, D., Li, X.J., Yu, Q.H., Xin, H.H.: Hybrid SiC-Si DC–AC topology: SHEPWM Si-IGBT master unit handling high power integrated with partial-power SiC-MOSFET slave unit improving performance. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 37(3), 3085–3098 (2022)

Zhang, L., Zheng, Z.S., Lou, X.T.: A review of WBG and Si devices hybrid applications. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 7(2), 1–20 (2021)

Rizzoli, G., Mengoni, M., Zarri, L., Tani, A., Serra, G., Casadei, D.: Comparative experimental evaluation of zero-voltage-switching Si inverters and hard-switching Si and SiC inverters. IEEE J. Emerg. Select. Top. Power Electron. 7(1), 515–527 (2019)

Gu, C., Wang, X.L., Deng, Z.Q.: Evaluation of three improved space-vector-modulation strategies for the high-speed permanent magnet motor fed by a SiC/Si hybrid inverter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 36(4), 4399–4409 (2021)

Li, C.S., Lu, R., Li, C.M., Li, Q.H., Gu, X.W., Fang, Y.T., Ma, H., He, X.N.: Space vector modulation for SiC and Si Hybrid ANPC converter in medium-voltage high-speed drive system. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 35(4), 3390–3401 (2020)

Lee, J., Lee, K.: Carrier-based discontinuous PWM method for vienna rectifiers. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 30(6), 2896–2900 (2015)

Lee, J., Lee, K.: Performance analysis of carrier-based discontinuous PWM method for vienna rectifiers with neutral-point voltage balance. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 31(6), 4075–4084 (2016)

Zhang, L., Zhao, R., Ju, P., Ji, C.H., Zou, Y.H., Ming, Y., Xing, Y.: A modified dpwm with neutral point voltage balance capability for three-phase Vienna rectifiers. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 36(1), 263–273 (2021)

Zou, Y.H., Zhang, L., Zhao, R., Xing, Y.: Discontinuous pulse width modulation and voltage harmonic analysis method for three-phase Vienna-type rectifiers. Proc. CSEE 40(24), 8123–8130 (2020)

Artal-Sevil, J.S., Bernal-Ruiz, C., Domínguez-Navarro, J.A., Bernal-Agustín, J.L.: Analysis of the DPWM technique applied to a grid-connected 3L-NPC inverter, in FACTS Technologies and Power Quality in smart Grid. 21st European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications (2019). https://doi.org/10.23919/EPE.2019.8915574

Liao, Y.H., Chen, J.Y., Zhou, Y.: A novel carrier scheme combined with DPWM technique in a ZVS grid-connected three-phase inverter. Electronics 11(4), 656 (2022)

Zou, Y.H., Zhang, L., Xing, Y., Zhang, Z., Zhao, H., Zheng, Z.S.: A unified carrier-based pulsewidth modulation for three-phase Vienna-type rectifiers. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 37(5), 5749–5762 (2022)

Jiang, W.D., Jiang, H.R., Liu, S.Y., Ji, S.Z., Wang, J.P.: A Carrier-Based Discontinuous PWM Strategy for T-Type Three-Level Converter With Reduced Common Mode Voltage, Switching Loss, and Neutral Point Voltage Control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 37(2), 1761–1771 (2022)

Gao, Z., Li, Y.H., Ge, Q.X., Zhao, L., Zhang, B.: Research on carrier-based improved synchronized discontinuous pulse width modulation for three-level inverter. Proc. CSEE 40(17), 5629–5635 (2020)

Zhang, D., He, J.B., Pan, D.: A megawatt-scale medium-voltage high-efficiency high power density “SiC+Si” hybrid three-level ANPC inverter for aircraft hybrid-electric propulsion systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 55(6), 5971–5980 (2019)

Guan, Q.X., Li, C.S., Zhang, Y., Wang, S., Xu, D.D., Li, W.H.: An extremely high efficient three-level active neutral-point-clamped converter comprising SiC and Si hybrid power stages. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 33(10), 8341–8352 (2018)

He, J., Zhang, D., Pan, D.: An improved PWM strategy for “SiC+Si” three-level active neutral point clamped converter in high-power high-frequency applications. IEEE Energy Convers. Congr. Expos. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/ECCE.2018.8557800

Deng, Y., Li, J., Shin, K.H., Viitanen, T., Saeedifard, M., Harley, R.G.: Improved modulation scheme for loss balancing of three-level active NPC converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 32(4), 2521–2532 (2017)

Zou, Y.H., Xing, Y., Zhang, L., Zheng, Z.S., Liu, X.L., Hu, H.B., Wang, T.Y., Wang, Y.S.: Dynamic-space-vector discontinuous PWM for three-phase Vienna rectifiers with unbalanced neutral-point voltage. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 36(8), 9015–9026 (2021)

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 52177176, and the Six Talent Peaks Project in Jiangsu Province under Grant 2019-TD-XNY-001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhuge, H., Zhang, L., Lou, X. et al. Evaluation of DPWM schemes for Si/SiC three-level hybrid active NPC inverters. J. Power Electron. 22, 1825–1835 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43236-022-00487-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43236-022-00487-x