Abstract

Members of the aquatic clade of reptiles Sauropterygia quickly evolved and diversified during the Triassic, acquiring different lifestyles and trophic roles with a cosmopolitan distribution. Although the first Triassic sauropterygian remains from the Iberian Peninsula were found more than a century ago, most of the relatively abundant recovered fossils have provided scarce taxonomic information. The finding of new fossil sites and taxa during the last decade, as well as the review of the previously known specimens, has allowed us to perform an update of the Iberian record of Triassic sauropterygians, a new faunal list being provided. All the major clades of Triassic sauropterygians are present in the Iberian Peninsula, including placodonts, pachypleurosaurs, pistosauroids and nothosauroids (i.e., simosaurids and nothosaurs). At least 13 different sauropterygian taxa are recognized here. The Iberian record of Triassic sauropterygians is composed by both endemic forms and species and genera also identified in other parts of the world, not only in some European regions, but also in the Middle East and China.

Resumen

Los reptiles acuáticos del clado Sauropterygia evolucionaron y se diversificaron rápidamente durante el Triásico, adquiriendo distintos modos de vida y nichos tróficos con una distribución cosmopolita. Aunque los primeros restos de sauropterigios triásicos de la península ibérica se descubrieron hace más de un siglo, la mayoría de estos fósiles relativamente abundantes han proporcionado escasa información taxonómica. El hallazgo de nuevos yacimientos y taxones durante la última década, así como la revisión de especímenes previamente conocidos, nos ha permitido llevar a cabo una puesta al día del registro ibérico de sauropterigios triásicos, proporcionando así un nuevo listado faunístico. Todos los principales clados de sauropterigios triásicos están presentes en la península ibérica, incluyendo placodontos, paquipleurosaurios, pistosauroideos y notosauroideos (i.e., simosáuridos y notosaurios). Se reconocen al menos 13 taxones diferentes de sauropterigios. El registro ibérico de sauropterigios triásicos está compuesto tanto por formas endémicas como por géneros y especies identificados en otras partes del planeta; no solo en algunas regiones europeas, sino también en Oriente Próximo y China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The sauropterygians composed a successful group of Mesozoic aquatic reptiles whose known record extends for more than 180 millions of years (Benson et al. 2010; Bardet et al. 2014), from the Early Triassic (Storrs 1991; Jiang et al. 2014) to the Late Cretaceous (Bakker 1993; Vincent et al. 2011). Quickly after its origin, Sauropterygia diversified into several clades which occupied different ecological niches, reaching the highest disparity of its evolutionary history during the Middle to early Late Triassic (Stubbs and Benton 2016). Thus, the record of the Triassic sauropterygians is well represented, abundant remains having been recovered from the margins of the Paleotethys Sea (i.e., Europe, North of Africa, the Middle East and China) and North America (Bardet et al. 2014).

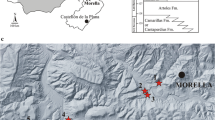

The first found Triassic sauropterygian specimen from the Iberian Peninsula of which there is currently evidence was an almost complete skeleton found in 1912 in Muschelkalk Facies (Ladinian, Middle Triassic) of the locality of Estada (Huesca Province, Aragon Autonomous Community, Spain). It belongs to the nothosaur Lariosaurus balsami Curioni 1847 (Ferrando 1912; Sanz 1976; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2014). However, most of the subsequently found Triassic sauropterygian remains in the Iberian Peninsula were fragmentary, isolated and poorly informative. Still, abundant material of this group has been recovered from several fossil sites and outcrops in the Portuguese area of Algarve (Campos and Mateus 2018), and also in several Spanish autonomous communities: Andalusia (Sanz 1991; Alafont 1992; Sanz et al. 1993; Niemeyer 2002; Reolid et al. 2014; Reolid and Reolid 2020), Aragon (Ferrando 1912; Lapparent 1966; Kuhn-Schnyder 1966; Sanz 1976; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2015; Navarro-Lorbés et al. 2016), Balearic Islands (Bauzá Rullán 1955), Castilla-La Mancha (Petit 1964; Le Joncour 1965; Mathieu 1965; Lapparent 1966; Westphal 1975; Sanz 1980, 1983, 1991; Alférez et al. 1983; López-Gómez 1985; Márquez-Aliaga and López-Gómez 1989; Pinna 1990; Alafont 1991, 1992, 1999; Sanz et al. 1993; Alafont and Sanz 1994; Berrocal-Casero and Castanhinha 2015; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2017, 2018a, b, 2020; Berrocal-Casero et al. 2018; Márquez-Aliaga et al. 2019), Castile and León (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2016), Catalonia (Almela and Llopis Lladó 1947; Via Boada et al. 1977; Sanz 1980, 1983; Sanz et al. 1993; Martínez-Delclòs 1995; Alafont and Sanz 1996; Rieppel and Hagdorn 1998; Quesada and Aguera González 2005; Fortuny et al. 2011) and Murcia (Pérez-Valera et al. 2019) (Fig. 1) (Table 1).

Fossil localities from the Iberian Peninsula where remains of the main Triassic sauropterygian clades have been found. The sites have been listed in chronological order according to the date of the first publication on each of them. The litostratigraphic and/or chronostratigraphic information for each site corresponds to that currently available in the literature. 1: Estada (Huesca, Spain; Ladinian, Muschelkalk Facies). 2: Olesa de Montserrat (Barcelona, Spain; Middle Triassic, Muschelkalk Facies). 3: Alpera (Albacete, Spain; Muschelkalk Facies). 4: Boniches (Cuenca, Spain; Anisian, Muschelkalk Facies). 5: Cañete (Cuenca, Spain; Middle Triassic, Muschelkalk Facies). 6: Torrijas (Teruel, Spain; Muschelkalk Facies). 7: Barranco de la Cazulla (Royuela, Teruel, Spain; Ladinian, Muschelkalk Facies). 8: Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona, Spain; Ladinian, Muschelkalk Facies). 9: Henarejos (Cuenca, Spain; Ladinian, Muschelkalk Facies). 10: Aiguafreda (Barcelona, Spain; Anisian, Muschelkalk Facies). 11: Canales de Molina (Guadalajara, Spain; Ladinian, Muschelkalk Facies). 12: Alcázar de San Juan (Ciudad Real, Spain; Keuper Facies). 13: Valdemeca (Cuenca, Spain; Muschelkalk Facies). 14: Bienservida (Albacete, Spain)—Villarrodrigo (Jaén, Spain)—Puente Génave (Jaén, Spain) (Middle Triassic, Muschelkalk Facies). 15: Riba de Santiuste—Rillo de Gallo (Guadalajara, Spain; Ladinian, Muschelkalk Facies). 16: Tordelrábano (Guadalajara, Spain; Middle Triassic). 17: Montealegre del Castillo (Albacete, Spain; Carnian, Keuper Facies). 18: Huélamo (Cuenca, Spain; Keuper Facies). 19: Siles (Jaén, Spain; probably Ladinian, Middle Triassic, Muschelkalk Facies). 20: Manzanera (Teruel, Spain; Carnian, Keuper Facies). 21: El Atance (Guadalajara, Spain; Carnian–Norian interval, Keuper Facies). 22: Vilanova de la Sal (Lleida, Spain; Carnian, Muschelkalk Facies). 23: Silves (Algarve, Portugal; Carnian). 24: Loulé (Algarve, Portugal; Carnian). 25: Fuencaliente de Medinaceli (Soria, Spain; Ladinian, Muschelkalk Facies). 26: Villora (Cuenca, Spain; Ladinian, Muschelkalk Facies). 27: Calasparra (Murcia, Spain; Ladinian, Muschelkalk Facies). 28: Sierra de Lújar (Granada, Spain; Ladinian)

Several compilations of the Iberian record of Triassic sauropterygians were performed in the past by Sanz (1980, 1983), Quesada et al. (1998), Bardet et al. (2008) and Fortuny et al. (2011). However, knowledge about this record has improved markedly during the last decade thanks to the finding of new fossil sites, the description of new sauropterygian taxa, and the review of several previously known specimens. An update of the Triassic record of the Iberian members of Sauropterygia is presented here, considering all these previous studies, as well as incorporating new data and discussions on several of the represented lineages (Table 1).

Institutional abbreviations: AM, Centre d’Historia Natural de la Conca de Barberà, Tarragona, Catalonia, Spain; IPS, Institut Català de Paleontologia, Sabadell, Catalonia, Spain; MAP, Museo Aragonés de Paleontología (Fundación Conjunto Paleontológico de Teruel-Dinópolis), Teruel, Spain; MGM, Museo Geominero, Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, Madrid, Spain; MGSB, Museu Geològic del Seminari Conciliar de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; MGUV, Museu de Geologia de la Universitat de València, València, Spain; MNCN, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid, Spain; MUPA-ATZ, El Atance collection, Museo de Paleontología de Castilla-La Mancha, Cuenca, Spain; UPUAM, Unidad de Paleontología, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain; VR, Bienservida-Villarrodrigo collection, deposited in the Departamento de Paleontología, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain.

2 Systematic palaeontology

The different Triassic sauropterygian taxa currently identify in the Iberian Peninsula, including placodonts (Fig. 2), pistosauroids (Fig. 3), pachypleurosaurs (Fig. 4), simosaurids (Fig. 5) and nothosaurs (Figs. 6, 7), are listed below, as well as the localities where they have been found:

Placodont and putative placodont remains from the Triassic of the Iberian Peninsula. a VR-428 (X90), indeterminate “placodontoid” scapula from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of the area of Bienservida and Villarrodrigo (Albacete and Jaén provinces, Spain). b MGM-284 T, partial dorsal carapace of Psephosauriscus from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Canales de Molina (Guadalajara Province, Spain). c MUPA ATZ0104, holotype of Parahenodus atancensis, from the Carnian or Norian (Upper Triassic) site of El Atance (Guadalajara Province, Spain). d-e MGM-296 T (d) and MGM-294 (e), isolated teeth of and indeterminate Placochelyidae from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Canales de Molina (Guadalajara Province, Spain). f MGSB-78.012, indeterminate juvenile cyamodontoid placodont from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona Province, Spain). g dorsal rib attributed by Pinna (1990) to the genus Paraplacodus, from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Henarejos (Cuenca Province, Spain), in lateral (g1) and anterior (g2) views (specimen without number, collection UPUAM)

Pachypleurosaur remains from the Triassic of the Iberian Peninsula. a MGSB-10.098, thoracic skeleton of an indeterminate pachypleurosaur from the Anisian (Middle Triassic) of Aiguafreda (Barcelona Province, Spain). b MGSB-63.281, cast of an indeterminate pachypleurosaur from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona Province, Spain). c IPS-51362, partial postcranial skeleton of an indeterminate pachypleurosaur from the Carnian (Upper Triassic) of Vilanova de la Sal (Lleida Province, Spain), probable representing a species different from those in a, b

Simosaurid remains from the Triassic of the Iberian Peninsula. a MAP-4769, isolated dorsal vertebra of an indeterminate Simosaurid from the Carnian (Upper Triassic) of Manzanera, not attributable to Paludidraco multidentatus, in anterior (a1), lateral (a2, a4) and posterior (a3) views. b MUPA-ATZ0101, holotype of Paludidraco multidentatus, from the Carnian or Norian (Upper Triassic) site of El Atance (Guadalajara Province, Spain)

Nothosaurian remains from the Triassic of the Iberian Peninsula. a MGUV-24447, holotype of Hispaniasaurus cranioelongatus, from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Villora (Cuenca Province, Spain), in dorsal (a1) and ventral (a2) views. b MGSB-M503, holotype of ‘Nothosaurus cymatosauroides’, from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona Province, Spain), currently identified as Nothosaurus sp. c VR-224 (X-87), isolated dorsal arch of Nothosaurus cf. mirabilis, from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of the area of Bienservida and Villarrodrigo (Albacete and Jaén provinces, Spain). d UPUAM 14702a, dorsal vertebrae of Nothosaurus cf. giganteus, from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Fuencaliente de Medinaceli (Soria Province, Spain)

a AM 024, postcranial skeleton of an indeterminate species of Lariosaurus not attributable to Lariosaurus balsami, from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona Province, Spain). b MNCN 63,704, skeleton of Lariosaurus balsami, from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Estada (Huesca Province, Spain). c MGSB-53.473 (M506), skeleton of Lariosaurus balsami, from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona Province, Spain)

Sauropterygia Owen 1860

Placodontiformes Neenan, Klein and Scheyer 2013

Placodontia Cope 1871

“Placodontoidea” Cope 1871

“Placodontoidea” indet.

Figure 2a

Global distribution of “Placodontoidea”: Lower Anisian to lower Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Europe and China (Rieppel 2000a; Jiang et al. 2008).

Iberian record: Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of the area of Bienservida and Villarrodrigo (Albacete and Jaén provinces, Spain) and Ladinian of Riba de Santiuste—Rillo de Gallo (Guadalajara Province, Spain) (Alafont 1992; Berrocal-Casero et al. 2018).

Cyamodontoidea Nopcsa 1923

Psephosauriscus Rieppel 2002

Psephosauriscus sp.

Figure 2b

Global distribution of the genus Psephosauriscus: Anisan to Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of the Middle East and the Iberian Peninsula (Rieppel 2002; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2020).

Iberian record: Ladinian (Middle Triassic; Muschelkalk Facies) of Canales de Molina (Guadalajara Province, Spain) (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2020).

Henodontidae Huene 1936

Parahenodus de Miguel Chaves, Ortega and Pérez-García 2018a

Parahenodus atancensis de Miguel Chaves, Ortega and Pérez-García 2018a

Figure 2c

Global distribution of the species Parahenodus atancensis: Exclusively known from its type locality and horizon, the Carnian to Norian (Late Triassic) fossil site of El Atance (Guadalajara Province, Spain) (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2018a).

Placochelyidae Romer 1956

Placochelyidae indet.

Figure 2d, e

Global distribution of the clade Placochelyidae: Ladinian (Middle Triassic) to Rhaetian (Late Triassic) of Europe and China (Rieppel 2000a; Li and Rieppel 2002; Zhao et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2019a).

Iberian record: Ladinian (Middle Triassic; Muschelkalk Facies) of Riba de Santiuste, Tordelrábano and Canales de Molina (Guadalajara Province, Spain) and Bienservida and Villarrodrigo (Albacete and Jaén provinces, Spain), and Keuper Facies of Alcázar de San Juan (Ciudad Real Province, Spain) (Pinna 1990; Sanz 1991; Alafont 1992, 1999; Sanz et al. 1993; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2020).

Eosauropterygia Rieppel 1994

Pistosauroidea indet.

Figure 3

Global distribution of the clade Pistosauroidea: Olenekian (Early Triassic) to Carnian (Late Triassic) of North America, Europe and China (Storrs 1991; Rieppel 2000a; Cheng et al. 2006; Dalla Vecchia 2006, 2017; Sato et al. 2010, 2014,2017a; Maisch 2014; Sander et al. 2014; Ma et al. 2015; Shang et al. ).

Iberian record: Ladinian (Middle Triassic; Muschelkalk Facies) of Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona Province, Spain) (Alafont and Sanz 1996).

Pachypleurosauria Nopcsa 1928

Pachypleurosauria indet.

Figures 4a, b

Global distribution of Pachypleurosauria: Olenekian (Early Triassic) to Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Europe and Asia (Rieppel 2000a; Bardet et al. 2014; Kowal-Linka and Bodzioch 2017; San et al. 2019; Klein and Sander 2019), its presence in the Carnian (Late Triassic) of China being currently debated (Klein and Sander 2019).

Iberian record: Anisian to Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Aiguafreda (Barcelona Province, Spain), Bienservida and Villarrodrigo (Albacete and Jaen provinces, Spain), Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona Province, Spain), Riba de Santiuste and Rillo de Gallo (Guadalajara Province, Spain), Valdemeca (Cuenca Province, Spain) and Siles (Jaén Province, Spain) (Sanz 1980, 1983, 1991; Alafont 1992, 1999; Rieppel and Hagdorn 1998; Niemeyer 2002).

Pachypleurosauria indet. sp. 2?

Figure 4c

Iberian record: Carnian (Late Triassic) of Vilanova de la Sal (Lleida Province, Spain) (Fortuny et al. 2011).

Nothosauroidea Baur 1889

Simosauridae Huene 1948a

Simosauridae indet. sp.1

Figure 5a

Global distribution of the clade Simosauridae: Anisian–Ladinian boundary (Middle Triassic) to the Carnian–Norian interval of Europe and the Middle East (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2018b, c, 2019a).

Iberian record: Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Riba de Santiuste (Guadalajara Province, Spain) and Carnian (Late Triassic) of Manzanera (Teruel Province, Spain) (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2015; Berrocal-Casero et al. 2018).

Paludidraco de Miguel Chaves, Ortega and Pérez-García 2018b

Paludidraco multidentatus de Miguel Chaves, Ortega and Pérez-García 2018b

Figure 5b

Global distribution of the species Paludidraco multidentatus: Exclusively known in its type locality and horizon, the Carnian to Norian (Upper Triassic) fossil site of El Atance (Guadalajara Province, Spain) (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2018b).

Nothosauria Baur 1889

Hispaniasaurus Márquez-Aliaga, Klein, Reolid, Plasencia, Villena and Martínez-Pérez 2019

Hispaniasaurus cranioelongatus Márquez-Aliaga, Klein, Reolid, Plasencia, Villena and Martínez-Pérez 2019

Figure 6a

Global distribution of the species Hispaniasaurus cranioelongatus: Exclusively known in its type locality and horizon, the Ladinian (Middle Triassic; Muschelkalk Facies) of Villora (Cuenca Province, Spain) (Márquez-Aliaga et al. 2019).

Nothosauridae Baur 1889

Nothosaurus Münster 1834

Nothosaurus sp.

Figure 6b

Global distribution of the genus Nothosaurus: Anisian (Middle Triassic) to Carnian (Late Triassic) of Europe, the Middle East and China (Rieppel 2000a; Liu et al. 2014; Hinz et al. 2019).

Iberian record: Middle Triassic (mostly Ladinian) of Royuela (Teruel Province, Spain) (Kuhn-Schnyder 1966), Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona Province, Spain) (Sanz 1983), Canales de Molina (Guadalajara Province, Spain) (Alférez et al. 1983; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2017), the area of Bienservida and Villarrodrigo (Albacete and Jaén Provinces, Spain) (Sanz 1991; Reolid et al. 2014), Siles (Jaén Province, Spain) (Niemeyer 2002), Puente Génave (Jaén Province, Spain) (Reolid et al. 2014) and Fuencaliente de Medinaceli (Soria Province, Spain) (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2016).

Nothosaurus cf. mirabilis Münster 1834

Figure 6c

Global distribution of the species Nothosaurus mirabilis: Anisian to Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Europe and the Middle East (Rieppel 2000a).

Iberian record: Muschelkalk Facies (Middle Triassic, probably Ladinian) of Royuela (Teruel Province, Spain), Siles (Jaén Province, Spain) and Puente Génave—Villarrodrigo (Jaén Province, Spain) (Kuhn-Schnyder 1966; Niemeyer 2002; Reolid et al. 2014).

Nothosaurus cf. giganteus Münster 1834

Figure 6d

Global distribution of the species Nothosaurus giganteus Anisian to Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Europe and the Middle East (Rieppel 2000a; Hinz et al. 2019). This taxon would survive into the Carnian (Late Triassic) according to Liu et al. (2014).

Iberian record: Ladinian (Muschelkalk Facies, Middle Triassic) of Fuencaliente de Medinaceli (Soria Province, Spain) (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2016).

Lariosaurus Curioni 1847

Lariosaurus (Ceresiosaurus) sp.

Figure 7a

Global distribution of the genus Lariosaurus: The fossil record of the genus Lariosaurus ranges from the Anisian (Middle Triassic) to the Carnian (Late Triassic) of Europe, the Middle East and China (Rieppel 1998, 2000a; Klein et al. 2016; Lin et al. 2017).

Iberian record: Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona Province, Spain) (Quesada and Aguera González 2005).

Lariosaurus balsami Curioni 1847

Figure 7b, c

Global distribution of the species Lariosaurus balsami: Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Europe (Rieppel 1998, 2000a).

Iberian record: Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Estada (Huesca Province, Spain) and Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona Province, Spain) (Sanz 1976; Rieppel and Hagdorn 1998).

3 Discussion

3.1 Placodontia

Placodonts are mostly durophagous sauropterygians whose record ranges from the Middle Triassic (Anisian) to the Late Triassic (Rhaetian) (Bardet et al. 2014). Fossil remains of this group have been found in several European countries (see a compilation in Rieppel 2000a; Bardet et al. 2014) and the Middle East (Haas 1975; Rieppel et al. 1999; Vickers-Rich et al. 1999; Rieppel 2002; Kear et al. 2010); its record was unknown in China until the XXI century, but it has rapidly increased in recent years (Li 2000; Li and Rieppel 2002; Jiang et al. 2008; Zhao et al. 2008; Neenan et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2019a, b, c).

Abundant but isolated and fragmentary remains of placodonts have been recovered from the Middle and Upper Triassic outcrops of the Iberian Peninsula, including the Portuguese area of Algarve (Campos and Mateus 2018); and the Spanish Autonomous Communities of Andalusia (Sanz 1991; Alafont 1992; Sanz et al. 1993; Niemeyer 2002; Reolid et al. 2014), Aragon (Lapparent 1966; Kuhn-Schnyder 1966; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2015), Castilla-La Mancha (Lapparent 1966; Westphal 1975; Márquez-Aliaga and López-Gómez 1989; Pinna 1990; Sanz 1991; Alafont 1992, 1999; Sanz et al. 1993; Berrocal-Casero and Castanhinha 2015; Berrocal-Casero et al. 2018; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2018a, 2020) and Catalonia (Rieppel and Hagdorn 1998). A detailed background about all these findings is included in de Miguel Chaves et al. (2020).

Despite the relatively abundance of placodont remains from the Iberian record, most of them provide scarce taxonomic information. Some Iberian specimens were attributed to the genera Placochelys Jaekel 1902, Psephoderma Meyer 1858 and Psephosaurus Fraas 1896 (Fig. 1f; Kuhn-Schnyder 1966; Westphal 1975; Rieppel and Hagdorn 1998; Alafont 1999; Niemeyer, 2002), but there is not information on the currently known specimens that justify their attributions to these taxa or their consideration as closely related forms (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2020).

Some carapace elements from the Carnian (Upper Triassic) of Algarve were assigned to the genus Henodus Huene 1936, based on their hexagonal and laterally elongated shape (Campos and Mateus 2018). However, this classification cannot currently be confirmed due to they have not been figured or described in detail. In fact, some isolated carapace elements from the Triassic locality of Manzanera (Teruel Province, Spain), MAP-4784 and MAP-4785, also present this morphology (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2015; Fig. 3f, g), being attributed to indeterminate cyamodontoid placodonts considering the absence of more informative characters.

After the first-hand study, we have not found enough evidence to justify the attribution of a dorsal rib from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Henarejos (Cuenca Province, Spain) to the genus Paraplacodus Peyer 1931a (Pinna 1990), contra de Miguel Chaves et al. (2020). The posterior uncinate process of the rib is partially broken (Fig. 2g), and it lacks the tapered distal end present in many of the dorsal ribs of Paraplacodus (Klein and Sichelschmidt 2014). This rib could be also compatible with those of other taxa as, for example, the diapsid Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi Nosotti and Rieppel 2003 (Scheyer et al. 2017). Therefore, its identification as belonging to the genus Paraplacodus cannot be supported, as was previously indicated by Rieppel (2000a, b). The attribution to Paraplacodus of a scapula from the same locality performed by Márquez-Aliaga and López-Gómez (1989) was not supported either (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2020).

Only two placodont taxa from the Iberian Peninsula can be currently identified at the generic level: Psephosauriscus Rieppel 2002 and Parahenodus de Miguel Chaves, Ortega and Pérez-García 2018a. Both taxa are cyamodontoid placodonts. An indeterminate species of the genus Psephosauriscus have been recently identified in the Muschelkalk Facies (Middle Triassic) of Canales de Molina (Guadalajara Province, Spain), based on a partial carapace (MGM-284T; Fig. 2b) of a probably juvenile individual (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2020). Psephosauriscus is a cyamodontoid placodont with uncertain affinities, previously identified in the Anisian to lower Ladinian levels of Israel and Egypt (Rieppel 2002). Therefore, its finding outside the Middle East expanded the previously known geographical range of this taxon. On the other hand, Parahenodus atancensis is a recently described genus and species from the Carnian or Norian (Upper Triassic) site of El Atance (Guadalajara Province, Spain), based on the partial skull MUPA ATZ0104 (Fig. 2c; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2018a). It is identified as the sister taxon of the bizarre cyamodontoid placodont Henodus chelyops Huene 1936, from the Carnian of Germany, both composing the highly specialized clade Henodontidae (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2018a).

In addition to these two cyamodontoid taxa identified at the generic level, remains of indeterminate “placodontoids” (i.e., non-shelled placodonts) were found in the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of the area of Bienservida and Villarrodrigo (Albacete and Jaén provinces, Spain; Fig. 2a), as well as placochelyid cyamodontoid remains in the same area, but also in the Keuper of Alcázar de San Juan (Ciudad Real Province, Spain), and the Muschelkalk (Middle Triassic) of Riba de Santiuste, Tordelrábano and Canales de Molina (Guadalajara Province, Spain) (Fig. 1d, e; Pinna 1990; Sanz 1991; Alafont 1992, 1999; Sanz et al. 1993; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2020).

Thus, at least three different forms of placodonts are identified in the Triassic of the Iberian Peninsula, including the genus Psephosauriscus (if it belonged to the clade Placochelyidae, as suggested by Mazin 1989; Rieppel 2001), the henodontid Parahenodus atancensis and indeterminate “placodontoids”. If Psephosauriscus does not belong to Placochelyidae, then the occurrence of placochelyid remains implies the presence of a fourth placodont form in the Iberian Triassic record.

3.2 Pistosauroidea

Pistosauroids were a group of eosauropterygians that gave origin to the members of the derived clade Plesiosauria during the Late Triassic (Wintrich et al. 2017). The oldest putative member of Pistosauroidea dates from the Olenekian (Early Triassic) (Storrs 1991), whereas the last known non-plesiosaur pistosauroids were recovered from the Carnian (Late Triassic) (Dalla Vecchia 2006, 2017). The geographical range of non-plesiosaurian pistosauroids (referred herein as pistosauroids) includes North America (Storrs 1991; Sander et al. 1997; Rieppel et al. 2002); Europe (Huene 1948b; Sues 1987; Rieppel 1997, 2000a; Rieppel and Werneburg 1998; Dalla Vecchia 2006, 2017; Maisch 2014; Sander et al. 2014) and China (Rieppel 1999; Cheng et al. 2006; Sato et al. 2010, 2014; Ma et al. 2015; Shang et al. 2017a).

The Iberian record of pistosauroids is very limited, consisting of a single specimen from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona Province, Spain) (Alafont and Sanz 1996). It is represented by the natural cast of the partial skull and complete jaw of a single individual (Fig. 3), kept in a private collection, identified by Alafont and Sanz (1996) as an indeterminate Pistosauria of the clade Pistosauridae (i.e., close to the genus Pistosaurus Meyer 1839). Rieppel and Hagdorn (1998) recognized this specimen as a probably indeterminate member of the clade Pistosauria, indicating that it presents the narrow and tapering snout recognized as exclusive for Pistosaurus. However, they also stated that it shows some characters not shared with this genus, including the lack of a sagittal crest and procumbent anterior dentary teeth, the presence of a homodont dentition and a tooth morphology that, according to them, could be not sauropterygian at all (Rieppel and Hagdorn 1998). Several Triassic pistosauroids have been published since then, sharing with Pistosaurus the tapering snout, the heterodonty, the procumbent anterior dentary teeth and the sagittal crest, and questioning the validity of the clades Pistosauria and Pistosauridae (Rieppel et al. 2002; Cheng et al. 2006; Sato et al. 2010, 2014; Ma et al. 2015; Shang et al. 2017a). Thus, several of the characters present in the individual from Mont-ral—Alcover are not shared with other pistosauroids and, therefore, this specimen could belong to a new taxon. However, due to the scarce nature of this fossil, its poor preservation and its problematic location in a private collection, we classify it as an indeterminate member of the clade Pistosauroidea, being the only specimen of this group currently known in the Triassic record of the Iberian Peninsula. In addition, some isolated vertebrae from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Calasparra (Murcia, Spain) has been proposed as probably related to pistosauroids (Pérez-Valera et al. 2019), but these remains are too scarce and fragmentary to confirm this attribution.

3.3 Pachypleurosauria

Pachypleurosaurs are small-sized eosauropterygians whose phylogenetic relationships are still debated, being interpreted by some authors as constituting a monophyletic group (Liu et al. 2011; Renesto et al. 2014), but recognized as paraphyletic by others (Cheng et al. 2016; Shang et al. 2017b; Jiang et al. 2018). The oldest worldwide confirmed pachypleurosaur remains have been recovered from the Olenekian (late Early Triassic), being attributed to the genus Dactylosaurus Gürich 1884 (Kowal-Linka and Bodzioch 2017); but two indeterminate pachypleurosaur specimens from Myanmar could also come from Lower Triassic levels (San et al. 2019). Most of the currently known pachypleurosaurs lived during the Anisian and Ladinian (Middle Triassic), the presence of this group in the Carnian (Late Triassic) being currently discussed (Klein and Sander 2019). Pachypleurosaurs have been found in several European countries (e.g., Rieppel 2000a; Bardet et al. 2014; Renesto et al. 2014; Klein and Sander 2019), as well as in Myanmar (San et al. 2019) and China (Holmes et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2011; Cheng et al. 2016; Shang et al. 2017b; Jiang et al. 2018).

Some pachypleurosaur remains have been identified in the Triassic of the Iberian Peninsula (Fig. 4), but none of them have been identified at the generic or specific levels. The first found Iberian pachypleurosaur was a partial specimen from the Anisian (Middle Triassic) of Aiguafreda (Barcelona Province, Spain), consisting of the thoracic region of an axial skeleton (Fig. 4a). It was classified by Sanz (1980, 1983) as an indeterminate Pachypleurosauridae. Several isolated vertebral remains from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of the area of Bienservida and Villarrodrigo (Albacete and Jaén provinces, Spain) were attributed to indeterminate pachypleurosaurs (Alafont 1991, 1992; Sanz 1991). The natural casts of three eosauropterygian specimens from the Ladinian of Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona Province, Spain) previously identified as Lariosaurus balsami (Sanz 1983), were reassigned by Rieppel and Hagdorn (1998) to a probably new taxon of Pachypleurosauria (Fig. 4b). Some isolated vertebral centra from the Middle Triassic of the area of Riba de Santiuste and Rillo de Gallo (Guadalajara Province, Spain), and from Valdemeca (Cuenca Province, Spain) were also attributed, in a preliminary way, to indeterminate pachypleurosaurs (Alafont 1999). In addition, some isolated vertebrae, ribs and teeth from the Muschelkalk (Middle Triassic) of Siles (Jaén Province, Spain) were also classified by Niemeyer (2002) as belonging to indeterminate members of this group. Finally, a partially articulated eosauropterygian skeleton from the basal Carnian (Upper Triassic) of Vilanova de la Sal (Lleida Province, Spain) was considered as Pachypleurosauria indet by Fortuny et al. (2011) (Fig. 4c). Some characters, as the presence of four sacral ribs in one of the specimens from Mont-ral—Alcover while the pachypleurosaur from Vilanova de la Sal only presents three, suggest that these specimens could belong to two different pachypleurosaur taxa. However, a detailed study of these remains is necessary in order to evaluate the validity of this hypothesis.

Thus, at least one pachypleurosaur taxon is present in the Middle-Late Triassic of the Iberian Peninsula, the presence of a second form being highly probable.

3.4 Simosauridae

Simosaurids are 3–4 m long Triassic eosauropterygians that belong to the clade Nothosauroidea, some of them being interpreted as predators (Rieppel 1994) and others were recently described as filter-feeders (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2018b). The temporal fossil record of Simosauridae ranges from the Anisian–Ladinian boundary (Middle Triassic; Haas 1981; Rieppel et al. 1999) to the Carnian–Norian interval (Late Triassic; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2018b). This clade seems to be restricted to the western Paleotethys, its remains having being found in several European countries (Rieppel 1996, 2000a; Dalla Vechia 2008; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2018b, c, 2019a) and in the Middle East (Haas 1981; Rieppel et al. 1999; Vickers-Rich et al. 1999; Kear et al. 2010).

Few confirmed simosaurid occurrences have been recognized in the Triassic record of the Iberian Peninsula (Fig. 5). The first Iberian simosaurid remains were found in the Carnian of Manzanera (Teruel Province, Spain), consisting of isolated vertebrae and ribs initially attributed to the genus Simosaurus Meyer 1842 (Fig. 5a; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2015). These remains have been recently reclassified as belonging to an indeterminate simosaurid (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2019a). The second Iberian occurrence is that of the recently described Paludidraco multidentatus de Miguel Chaves, Ortega and Pérez-García 2018b, from the Carnian or Norian fossil site of El Atance (Guadalajara Province, Spain), which has been interpreted as a filter-feeder (Fig. 5b; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2018b). The fossils from Manzanera have been interpreted as belonging to an indeterminate form, different from Paludidraco multidentatus (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2019a), so two different simosaurid forms are identified in the Iberian Peninsula. A third simosaurid occurrence has been cited from the Ladinian of Riba de Santiuste (Guadalajara Province, Spain), based on a single vertebral centrum that could correspond to Simosaurus or a related form (Berrocal-Casero et al. 2018; Fig. 10). Due to the little information provided by this single element we opt to classify it as belonging to an indeterminate simosaurid. Finally, an isolated dorsal rib from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of the Sierra de Lújar (Granada Province, Spain) shares with those of Paludidraco multidentatus a strong distal expansion, a constricted proximal region and pachyostosis of the bone (Reolid and Reolid 2020), and they suggested that it could belong to this taxon. However, due to the scarce information provided by this isolated element, the authors decided to classify it just as an indeterminate eosauropterygian, probably belonging to the clade Simosauridae (Reolid and Reolid 2020). We agree with them.

3.5 Nothosauria

Nothosauria is the other clade included within Nothosauroidea, being the sister group of Simosauridae. They were eosauropterygians ranging from small (less than 1 m in length) to large size (5–7 m length), some of them being apex predators (Liu et al. 2014). They have been found in lower Anisan (Middle Triassic) to lower Carnian (Upper Triassic) levels from Europe, China, Israel and Tunisia (e.g. Rieppel 2000a; Bardet et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2014; Klein et al. 2016; Lin et al. 2017; Hinz et al. 2019).

The nothosaurian remains are amongst the most abundant sauropterygian fossils from the Iberian Triassic, although most of them are poorly informative. Indeterminate nothosaur remains have been recovered from several localities of the Iberian Peninsula, including Royuela (Teruel Province, Spain) (Kuhn-Schnyder 1966), Henarejos (Cuenca Province, Spain) (Sanz 1983), Valdemeca (Cuenca Province, Spain) (López-Gómez 1985; Alafont 1999), the area of Bienservida and Villarrodrigo (Albacete and Jaén provinces, Spain) (Sanz 1991; Alafont 1991, 1992), the area of Riba de Santiuste and Rillo de Gallo (Guadalajara Province, Spain) (Alafont 1999; Berrocal-Casero et al. 2018), Siles (Jaén Province, Spain) (Niemeyer 2002), El Atance (Guadalajara Province) (Quesada et al. 2009; de Miguel Chaves et al.); the area of Puente Génave and Villarrodrigo (Jaén Province, Spain) (Reolid et al. 2014) and Canales de Molina (Guadalajara Province, Spain) (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2017).

The genus Nothosaurus Münster 1834 or very closely related forms, were identified several times in the Iberian Triassic record, in the localities of Olesa (Barcelona Province, Spain) (Almela and Llopis Lladó 1947), Sóller (Mallorca, Balearic Islands, Spain) (Bauzá Rullán 1955), Royuela (Teruel Province, Spain) (Kuhn-Schnyder 1966), Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona Province, Spain) (Sanz 1983), Canales de Molina (Guadalajara Province, Spain) (Alférez et al. 1983; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2017), the area of Bienservida and Villarrodrigo (Albacete and Jaén provinces, Spain) (Sanz 1991; Reolid et al. 2014), Siles (Jaén Province, Spain) (Niemeyer 2002), Puente Génave (Jaén Province, Spain) (Reolid et al. 2014) and Fuencaliente de Medinaceli (Soria Province, Spain) (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2016). However, the remains of the two first localities (i.e., Olesa and Sóller) have not been properly described nor figured, its attribution being doubtful (Sanz 1980, 1983). The study of the Spanish vertebral remains attributed to Nothosaurus has provided evidence of the presence of two different forms within this genus in the Iberian Triassic record, one of them being more close to Nothosaurus mirabilis Münster 1834 (Fig. 6c) and other related to Nothosaurus giganteus Münster 1834 (Fig. 6d; de Miguel Chaves et al. 2016). In addition, another species of this genus was erected based on the natural cast of a skull, vertebrae, ribs and gastral elements of a single individual from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona Province, Spain): Nothosaurus cymatosauroides Sanz 1983 (Fig. 6b). The validity of this taxon was subsequently questioned by Rieppel (2000a). The diagnosis of N. cymatosauroides was based on a combination of characters, including: a relatively short and wide face when compared to other Nothosaurus species, a marked orbital development in relation to the pre-temporal cranial region, a transverse development of the postorbital region followed by a marked constriction in the post-temporal region, the presence of relatively small upper temporal fenestrae when compared to those of other species within the genus (the length being 2.3 times the length of the orbits), and the presence of a laterally expanded squamosal (Sanz 1983; Rieppel and Hagdorn 1998; Rieppel 2000a). However, this combination of characters is also present in the small sized species of the same genus Nothosaurus marchicus Koken 1893 and Nothosaurus winterswijkensis Albers and Rieppel 2003 (see Koken 1893; Rieppel and Hagdorn 1998; Albers and Rieppel 2003; Albers 2005). In addition, the lack of visible sutures in the holotype of N. cymatosauroides due to its preservation as a natural cast also prevent to support the validity of this species.

Two different species of the nothosaurian genus Lariosaurus Curioni 1847 have also been identified in the Triassic levels of the Iberian Peninsula (Fig. 7). Several specimens of the type species, Lariosaurus balsami, have been found in two Spanish localities: one single individual from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Estada (Huesca Province, Spain; Ferrando 1912; Sanz 1976) (Fig. 7b), and six specimens from the Ladinian of Mont-ral—Alcover (Tarragona Province, Spain; Sanz 1983; Rieppel and Hagdorn 1998) (Fig. 7c). A second Lariosaurus species was recovered also from the Ladinian of Mon-ral—Alcover, based on the natural cast of a partial postcranial skeleton (AM 024; Fig. 7a), and attributed to the species Lariosaurus calcagnii by Rieppel and Hagdorn (1998), or to an indeterminate species of the problematic genus Ceresiosaurus Peyer 1931b by Quesada and Aguera González (2005). Ceresiosaurus is a doubtful nothosaur genus that comprises two species (C. calcagnii and C. lanzi Hänni 2004), and that was synonymized with the genus Lariosaurus by Rieppel (1998), although it was reconsidered as valid by Hänni (2004). However, most of the recent studies identify C. calcagnii as a species within the genus Lariosaurus (L. calcagnii) and obviate C. lanzi (Klein et al. 2016; Lin et al. 2017; Hinz et al. 2019). Taking this into account, and considering that Quesada and Aguera González (2005) were not confident to include the specimen AM 024 within the species Lariosaurus (Ceresiosaurus) calcagnii, we identify it as a Lariosaurus species different to L. balsami. More detailed studies are necessary in order to evaluate its specific attribution.

Finally, a new eosauropterygian taxon with nothosaurian affinities, Hispaniasaurus cranioelongatus Márquez-Aliaga, Klein, Reolid, Plasencia, Villena and Martínez-Pérez 2019, has been described based on a partial skull (Fig. 6a) from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of Villora (Cuenca Province, Spain) (Márquez-Aliaga et al. 2019). Phylogenetic analysis identify Hispaniasaurus cranioelongatus as a nothosauroid, being closer than Simosaurus to the Nothosaurus-Lariosaurus clade, and therefore being its sister taxon (Márquez-Aliaga et al. 2019), and sharing with Nothosauria the following synapomorphies: reduced dorsal exposure of the prefrontal; jugal restricted to a position behind the orbit; external nares retracted with a longitudinal diameter approaching or exceeding half the longitudinal diameter of orbit; and postfrontal with reduced lateral process and hence more of an elongate shape (de Miguel Chaves 2018).

Thus, at least five different nothosaurian taxa are present in the Iberian Triassic record, including two different forms of Nothosaurus (but N. cymatosauroides not being currently recognized as a valid form), two species of the genus Lariosaurus (one of them being L. balsami and the other not identified at specific level) and Hispaniasaurus cranioelongatus.

4 The Iberian Triassic sauropterygians in the paleobiogeographical context

The sauropterygian record from the Triassic levels of the Iberian Peninsula is composed of both endemisms and species and genera present in other regions. The record of the Iberian placodonts is consistent with the range of this group, known from the Anisian to the Rhaetian of Europe, the Middle East and China (Bardet et al. 2014; Neenan et al. 2015). The genus Psephosauriscus was only known from the Anisian and lower Ladinian of the Middle East (Rieppel 2002), so its presence in the Ladinian of the Iberian Peninsula (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2020) expanded its geographical range, suggesting a dispersion from the Sephardic Domain during the Ladinian or before. Parahenodus atancensis is a form exclusively known in the Iberian Peninsula (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2018a). Its occurrence in the Carnian is consistent with the temporal distribution of its sister taxon, Henodus chelyops, from the Carnian of Tübingen (Germany) (Huene 1936). This would be also consistent with the possible presence of osteoderms of a henodontid in the Carnian of Algarve (Portugal) (identified as Henodus by Campos and Mateus 2018), and with the occurrence of other elements with the same morphology in the Carnian of Manzanera (Teruel Province, Spain) (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2015). In fact, taking into account that the morphology of the carapace of Parahenodus atancensis is currently unknown, and that it is closely related to Henodus chelyops, the possibility that these elements belong to Parahenodus atancensis cannot be ruled out.

The presence of both pistosauroids and pachypleurosaurs in the Anisian and Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of the Iberian Peninsula (Sanz 1983; Alafont and Sanz 1996; Rieppel and Hagdorn 1998) is also consistent with the known record of these sauropterygian groups. Pistosauroidea record ranges from the Olenekian (Early Triassic) to the Carnian (Late Triassic) of North America, Europe and China (e.g., Bardet et al. 2014), and pachypleurosaur forms are known from the Olenekian and lived mostly during the Anisian-Ladinian interval in Europe and Asia (e.g. Klein and Sander 2019). However, considering that the presence of the pachypleurosaurs during the Carnian (Late Triassic) is currently subject of discussion (Klein and Sander 2019), the occurrence of a pachypleurosaur specimen in the Carnian of Catalonia (Fortuny et al. 2011) confirms the presence of this group, representing one of the youngest known records.

The only identified simosaurid taxon from the Iberian Triassic at both specific and generic level is Paludidraco multidentatus, from the Carnian—Norian (Late Triassic) of El Atance (Guadalajara Province, Spain) (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2018b). This taxon is currently recognized as exclusive of the Spanish record. Another indeterminate simosaurid taxon is identified in Carnian levels of the Iberian Peninsula (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2015), and more indeterminate simosaurid fossils are known from the Ladinian of Riba de Santiuste (Berrocal-Casero et al. 2018). The age of these Iberian remains of this clade is consistent with that of the known record of Simosauridae, which ranges from the Anisian-Ladinian (Middle Triassic) boundary to the Carnian, in Europe and the Middle East (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2019a). The absence of simosaurid remains in China suggests the origin and diversification of this clade as exclusive of the Western Paleotethys. If the single dorsal rib from the Ladinian of the Sierra de Lújar (Granada Province, Spain) finally belongs to Paludidraco multidentatus, as suggested by Reolid and Reolid (2020), it would correspond to the oldest record of this taxon.

The Iberian record of Nothosauria is also composed of endemic forms and taxa shared with other regions. The Iberian record of the genus Nothosaurus is limited to the Middle Triassic (de Miguel Chaves et al. 2016), its global record ranging from the Anisian (lower stage of the Middle Triassic) to the Carnian (Late Triassic) of Europe, the Middle East and China (see Liu et al. 2014 Fig. 3; Hinz et al. 2019; Fig. 9). The two forms of Lariosaurus from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of the Iberian Peninsula, Lariosaurus balsami (Sanz 1976; Rieppel and Hagdorn 1998) and a second indeterminate species, not attributable to it (Quesada and Aguera González 2005) are also compatible with the known global geographical and temporal record of this genus. This taxon is known from the Anisian (Middle Triassic) to the lower Carnian (Late Triassic) of Europe, the Middle East and China (see Klein et al. 2016; Lin et al. 2017). Finally, the recently described Hispaniasaurus cranioelongatus (Márquez-Aliaga et al. 2019), from the Ladinian of Villora (Cuenca Province, Spain), is currently recognized exclusively from its type locality.

5 Conclusions

Sauropterygia has traditionally been a poorly known clade in the Triassic record of the Iberian Peninsula. Although the first Triassic sauropterygian specimen was found at the beginning of the XX century, most of the so far found remains were isolated and fragmentary, and only some of them, described during the 1980s and 1990s, could be identified at genus or species level. The finding of new fossil sites and the publication of new sauropterygian taxa in recent years has allowed us to perform here a review and an update of the fossil record of this group in the Iberian Triassic.

All the major clades of Triassic sauropterygians known worldwide are present in the Iberian Peninsula: placodonts, pistosauroids, pachypleurosaurs and nothosauroids. At least 13 different sauropterygian taxa are identified here for the Iberian Triassic record: three different forms of placodonts (indeterminate “placodontoids”, the genus Psephosauriscus and Parahenodus atancensis), an indeterminate pistosauroid, two probable different pachypleurosaurs, two different simosaurids (Paludidraco multidentatus and an indeterminate simosaurid not attributable to it), and five members of Nothosauria, including two different indeterminate species of Nothosaurus, two forms of Lariosaurus (L. balsami and an indeterminate species of Lariosaurus that differs from it) and Hispaniasaurus cranioelongatus. This number could be higher if the genus Psephosauriscus, with uncertain phylogenetic affinities, does not belong to the clade Placochelyidae, due to placochelyid remains have been also identified in the Iberian Triassic. The previously considered presence of the placodont genera Paraplacodus and Henodus in the Iberian record, and the validity of Nothosaurus cymatosauroides, cannot be currently supported.

References

Alafont, L. S. (1991). Notosaurios y Placodontos (Reptilia) del Triásico Medio de Biernservida-Villarrodrigo (Albacete-Jaén). Tesis de licenciatura. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

Alafont, L. S. (1992). Notosaurios y Placodontos (Reptilia) del Triásico Medio de Bienservida-Villarrodrigo. Albacete: Instituto de Estudios albacetenses de la Excma, Diputación de Albacete.

Alafont, L. S. (1999). Reptiles del Triásico. In A. Aguirre & I. Rábano (Eds.), La huella del pasado: Fósiles de Castilla-La Mancha (pp. 143–159). La Mancha: Junta de Comunidades de Castilla.

Alafont, L. S., Sanz, J. L. (1994). Nuevos hallazgos de notosaurios y placodontos (Reptilia) en el Triásico Ibérico. In Resúmenes del III Coloquio de Estratigrafía y Paleogeografía del Pérmico y Triásico de España, Cuenca.

Alafont, L. S., & Sanz, J. L. (1996). Un nuevo sauropterigio (Reptilia) en el Triásico de la Sierra de Prades (Tarragona). Cuadernos de Geología Ibérica, 20, 313–329.

Albers, P. C. H. (2005). A new specimen of Nothosaurus marchicus with features that relate the taxon to Nothosaurus winterswijkensis. PalArch’s Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology, 3(1), 1–7.

Albers, P. C. H., & Rieppel, O. (2003). A new species of the sauropterygian genus Nothosaurus from the lower Muschelkalk of Winterswijk, The Netherlands. Journal of Paleontology, 77(4), 738–744. https://doi.org/10.1666/0022-3360(2003)077<0738:ANSOTS>2.0.CO;2.

Alférez, F., Molero, G., Maldonado, E. (1983). Un nuevo yacimiento con vertebrados fósiles (Peces y Reptiles) en el Trías de la Cordillera Ibérica (Canales de Molina, Guadalajara). In Real Sociedad Española de Historia Natural. VI Reunión Bienal, Santiago (p. 44).

Almela, A., Llopis Lladó, N. (1947). Hoja geológica num. 392 (Sabadell). Mapa Geológico de España E. 1:50.000. Segunda serie, I.G.M.E., Madrid.

Bakker, R. T. (1993). Plesiosaur extinction cycles - Events that mark the beginning, middle and end of the Cretaceous. In W. G. E. Caldwell & E. G. Kauffman (Eds.), Evolution of the Western Interior Basin (pp. 641–664). St. Johns: Geological Association of Canada.

Bardet, N., Pereda Suberbiola, X., & Ruiz-Omeñaca, J. I. (2008). Mesozoic marine reptiles from the Iberian Peninsula. Geo-Temas, 10, 1245–1248.

Bardet, N., Falconnet, J., Fischer, V., Houssaye, A., Jouve, S., Pereda Suberbiola, X., et al. (2014). Mesozoic marine reptile palaeobiogeography in response to drifting plates. Gondwana Research, 26, 869–887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2014.05.005.

Baur, G. (1887–1890). Pistosauridae Baur. In K. A. Zittel (Ed.), Handbuch der Palaeontologie, Vol. 3 (pp. 498–499). München: R. Oldenbourg.

Baur, G. (1889). Palaeohatteria Credner, and the Proganosauria. American Journal of Science, 37(3), 310–313.

Bauzá Rullán, J. (1955). Notas paleontológicas de Mallorca: sobre el hallazgo del Nothosaurus en el Trias. Boletín de la Sociedad de Historia Natural de Baleares, 1, 87.

Benson, R. B., Butler, R. J., Lindgren, J., & Smith, A. S. (2010). Mesozoic marine tetrapod diversity: mass extinctions and temporal heterogeneity in geological megabiases affecting the vertebrates. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 277, 829–834. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.1845.

Berrocal-Casero, M., & Castanhinha, R. (2015). Nuevos hallazgos de vertebrados triásico en el anticlinal de Riba de Santiuste (Guadalajara, España). In G. Arreguín-Rodríguez, J. Colmenar, E. Díaz-Berenguer, J. Galán, A. Legarda-Lisarri, J. Parrilla-Bel, E. Puértolas-Pascual, & R. Silva-Casal (Eds.), New Insights on Ancient Life (pp. 58–59). Zaragoza: Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza.

Berrocal-Casero, M., Audije-Gil, J., Castanhinha, R. A., Pérez-Valera, J. A., Faria dos Santos, V., & Segura, M. (2018). New discoveries of vertebrate remains from the Triassic of Riba de Santiuste, Guadalajara (Spain). Proceedings of the Geologists' Association, 129(4), 526–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pgeola.2018.04.009.

Campos, H., Mateus, O. (2018). The first record of placodonts in Portugal and its chronological and paleoecological implications. In Abstract book of the XVI annual meeting of the European Association of Vertebrate Palaeontologists, Caparica, Portugal (p. 38).

Cheng, Y.-N., Sato, T., Wu, X.-C., & Li, C. (2006). First complete pistosauroid from the Triassic of China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 26, 501–504. https://doi.org/10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[501:FCPFTT]2.0.CO;2.

Cheng, Y., Wu, X., Sato, T., & Shan, H. (2016). Dawazisaurus brevis, a new eosauropterygian from the Middle Triassic of Yunnan, China. Acta Geologica Sinica (English Edition), 90(2), 401–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-6724.12680.

Cope, E. D. (1871). The systematic arrangement of the Reptilia. Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, 19, 226–247.

Curioni, G. (1847). Cenni sopra un nuovo saurio fossile dei monti di Perledo sul Lario e sul terreno che lo racchiude. Giornale del' J.R. Instituto Lombardo di Scienze, Lettre ed Arti, 16, 159–170.

Dalla Vecchia, F. M. (2006). A new sauropterygian reptile with plesiosaurian affinity from the late Triassic of Italy. Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia, 112, 207–225.

Dalla Vechia, F. M. (2008). First record of Simosaurus (Sauropterygia, Nothosauroidea) from the Carnian (Late Triassic) of Italy. Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia, 114, 273–285.

Dalla Vecchia, F. M. (2017). Comments on the skeletal anatomy of the Triassic reptile Bobosaurus forojuliensis (Sauropterygia, Pistosauroidea). Gortania. Geologia, Paleontologia, Paletnologia, 38, 39–75.

de Miguel Chaves, C. (2018). Historia evolutiva de Simosauridae (Sauropterygia). Contexto sistemático y biogeográfico de los reptiles marinos del Triásico de la península ibérica. Ph.D thesis. Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Madrid, Spain.

de Miguel Chaves, C., Pérez-García, A., & Ortega, F. (2014). Perspectiva histórica del ejemplar de Lariosaurus (Sauropterygia) de Estada (Huesca). In G. Arreguín-Rodríguez, J. Colmenar, E. Díaz-Berenguer, J. Galán, A. Legarda-Lisarri, J. Parrilla-Bel, E. Puértolas-Pascual, & R. Silva-Casal (Eds.), New Insights on Ancient Life (pp. 203–206). Zaragoza: Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza.

de Miguel Chaves, C., Pérez-García, A., Cobos, A., Royo-Torres, R., Ortega, F., & Alcalá, L. (2015). A diverse Late Triassic tetrapod fauna from Manzanera (Teruel, Spain). Geobios, 48, 479–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geobios.2015.09.002.

de Miguel Chaves, C., García-Gil, S., Ortega, F., Sanz, J. L., & Pérez-García, A. (2016). First Triassic tetrapod (Sauropterygia, Nothosauridae) from Castilla y León: Evidence of an unknown taxon for the Spanish record. Journal of Iberian Geology, 42(1), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_JIGE.2016.v42.n1.51210.

de Miguel Chaves, C., Ortega, F., & Pérez-García, A. (2017). The eosauropterygian fossils from the Middle Triassic of Canales de Molina (Guadalajara, Spain). Journal of Iberian Geology, 43(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41513-017-0011-9.

de Miguel Chaves, C., Ortega, F., & Pérez- García, A. (2018a). A new placodont from the Upper Triassic of Spain provides new insights on the acquisition of the specialized skull of Henodontidae. Papers in Palaeontology, 4(4), 567–576. https://doi.org/10.1002/spp2.1218.

de Miguel Chaves, C., Ortega, F., & Pérez-García, A. (2018b). New highly pachyostotic nothosauroid interpreted as a filter feeding Triassic marine reptile. Biology Letters, 14, 20180130. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2018.0130.

de Miguel Chaves, C., Ortega, F., & Pérez-García, A. (2018c). Cranial variability of the European Middle Triassic sauropterygian Simosaurus gaillardoti. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 63, 315–326. https://doi.org/10.4202/app.00471.2018.

de Miguel Chaves, C., Ortega, F., & Pérez-García, A. (2019a). On the validity of the Middle Triassic sauropterygian ‘Partanosaurus zitteli’ and the diversity of Simosauridae. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 39(5), e1704770. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2019.1704770.

de Miguel Chaves, C., Ortega, F., Pérez-García, A. (2019b): The Spanish Upper Triassic vertebrate site of El Atance: an update. In J. A. Moreno Bedmar (Ed.), Paleontología Mexicana Volumen Especial 4: X Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología. El Salvador 2019 (p. 104).

de Miguel Chaves, C., Scheyer, T. M., Ortega, F., & Pérez-García, A. (2020). The placodonts (Sauropterygia) from the Middle Triassic of Canales de Molina (Central Spain), and an update on the knowledge about this clade in the Iberian record. Historical Biology, 32(1), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2018.1462805.

Ferrando, P. (1912). Sobre el reptil fósil sauropterigido notosaurido, encontrado en Estada (Huesca). Boletín de la Real Sociedad Española de Historia Natural, 12, 188.

Fortuny, J., Bolet, A., Sellés, A. G., Cartanyà, J., & Galobart, À. (2011). New insights on the Permian and Triassic vertebrates from the Iberian Peninsula with emphasis on the Pyrenean and Catalonian basins. Journal of Iberian Geology, 37, 65–86. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_JIGE.2011.v37.n1.5.

Fraas, E. (1896). Die Schwäbischen Trias-Sauder. Stuttgart: E. Schweizerbart.

Gürich, G. J. E. (1884). Über einige Saurier des Oberschlesischen Muschelkalkes. Zeitschrift der deutschen Geologischen Gesellschaft, 36, 125–144.

Haas, G. (1975). On the placodonts of the Wadi Ramon area Muschelkalk. Colloque international, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 218, 451–456.

Haas, G. (1981). A fragmentary skull of Simosaurus (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Middle Triassic of the Makhtesh Ramon, Israel. Israel Journal of Zoology, 30, 30–34.

Hänni, K. (2004). Die Gattung Ceresiosaurus. Ceresiosaurus calcagnii PEYER und Ceresiosaurus lanzi n. sp. (Lariosauridae, Sauropterygia). Ph.D thesis. Zürich: vdf, Hochschulverlag an der ETHZ.

Hinz, J. K., Matzke, A. T., & Pfretzschner, H.-U. (2019). A new nothosaur (Sauropterygia) from the Ladinian of Vellberg-Eschenau, southern Germany. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2019.1585364.

Holmes, R., Cheng, Y.-N., & Wu, X.-C. (2008). New information on the skull of Keichousaurus hui (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) with comments on sauropterygian interrelationships. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 28(1), 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[76:NIOTSO]2.0.CO;2.

Huene, F. V. (1936). Henodus chelyops, ein neuer Placodontier. Palaeontographica A, 84, 99–148.

Huene, F. V. (1948a). Simosaurus and Corosaurus. American Journal of Science, 246, 41–43.

Huene, F. V. (1948b). Pistosaurus, a Middle Triassic plesiosaur. American Journal of Science, 246, 46–52.

Jaekel, O. (1902). Über Placochelys n. g. und ihre Bedeutung für die Stammesgeschichte der Schildkröten. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen, 1, 127–144.

Jiang, D.-Y., Motani, R., Hao, W.-C., Rieppel, O., Sun, Y.-L., Schmitz, L., et al. (2008). First record of Placodontoidea (Reptilia, Sauropterygia, Placodontia) from the Eastern Tethys. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 28, 904–908. https://doi.org/10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[904:FROPRS]2.0.CO;2.

Jiang, D.-Y., Motani, R., Tintori, A., Rieppel, O., Chen, G.-B., Huang, J.-D., et al. (2014). The Early Triassic eosauropterygian Majiashanosaurus discocoracoidis, gen. et sp. nov. (Reptilia, Sauropterygia), from Chaohu, Anhui Province, People’s Republic of China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 34(5), 1044–1052. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2014.846264.

Jiang, D.-Y., Lin, W.-B., Rieppel, O., Motani, R., & Sun, Z.-Y. (2018). A new Anisian (Middle Triassic) eosauropterygian (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) from Panzhou, Guizhou Province, China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 38(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2018.1480113.

Kear, B. P., Rich, T. H., Vickers-Rich, P., Ali, M. A., Al-Mufarrih, Y. A., Matari, A. H., et al. (2010). A review of aquatic vertebrate remains from the Middle-Upper Triassic Jilh Formation of Saudi Arabia. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria, 122, 1–8.

Klein, N., Sander, P.M. (2019): Anarosaurus heterodontus—the least aquatic pachypleurosaur. In D. F. A. E Voeten., et al. (Eds), Grondboor & Hamer 73 (5/6)—Staringia 16 (pp. 226–233).

Klein, N., & Sichelschmidt, O. J. (2014). Remarkable dorsal ribs with distinct uncinated processes from the early Anisian of the Germanic Basin (Winterswijk, The Netherlands). Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie Abhandlungen, 271, 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1127/0077-7749/2014/0391.

Klein, N., Voeten, D. F. A. E., Haarhuis, A., & Bleeker, R. (2016). The earliest record of the genus Lariosaurus from the early middle Anisian (Middle Triassic) of the Germanic Basin. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 36(4), e1163712. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2016.1163712.

Koken, E. (1893). Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Gattung Nothosaurus. Zeitschrift der deutschen Geologischen Gesellschaft, 45, 337–377.

Kowal-Linka, M., & Bodzioch, A. (2017). Genesis of the Lower Triassic bonebeds from Gogolin (S Poland): the impact of microbial mats on trapping of vertebrate remains. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 466, 38–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.11.010.

Kuhn-Schnyder, E. (1966). Über Wirbeltier-Reste aus dem Muschelkalk der Provinz Teruel (Spanien). Oberrhein. Geol. Abh., 15, 99–106.

Lapparent, A. F. (1966). Noveaux gisements de reptiles mesozoiques en Espagne. Notas y Comunicaciones del Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, 84, 103–110.

Le Joncour, M. (1965): Description géologique des environs de Cañete (Cuenca).Diplôme d’étudiant.

Li, C. (2000). Placodont (Reptilia: Placodontia) from Upper Triassic of Guizhou, Southwest China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 38, 314–317.

Li, C., & Rieppel, O. (2002). A new cyamodontoid placodont from Triassic of Guizhou, China. Chinese Science Bulletin, 47, 403–407.

Lin, W.-B., Jiang, D.-Y., Rieppel, O., Motani, R., Ji, C., Tintori, A., et al. (2017). A new specimen of Lariosaurus xingyiensis (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) Zhuganpo Member, Falang Formation, Guizhou, China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 37(2), e1278703. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2017.1278703.

Liu, J., Rieppel, O., Jiang, D., Aitchison, J. C., Motani, R., Zhang, Q.-Y., et al. (2011). A new pachypleurosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Lower Middle Triassic of Southwestern China and the phylogenetic relationships of Chinese pachypleurosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 31, 292–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2011.550363.

Liu, J., Hu, S.-X., Rieppel, O., Jiang, D.-Y., Benton, M. J., Kelley, N. P., et al. (2014). A gigantic nothosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Middle Triassic of SW China and its implication for the Triassic biotic recovery. Scientific Reports, 4(7142), 1–9.

López-Gómez, J. (1985). Sedimentología y estratigrafía de los materiales pérmicos y triásicos del sector SE de la Rama Castellana de la Cordillera Ibérica entre Cueva de Hierro y Chelva (provincias de Cuenca y Valencia). Seminarios de Estratigrafía, Serie Monografías, 11, 1–344.

Ma, L. T., Jiang, D.-Y., Rieppel, O., Motani, R., & Tintori, A. (2015). A new pistosauroid (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) from the late Ladinian Xingyi marine reptile level, southwestern China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 35(1), e881832. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2014.881832.

Maisch, M. W. (2014). A well preserved skull of Cymatosaurus (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the uppermost Buntsandstein (Middle Triassic) of Germany. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Abhandlungen, 272(2), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1127/0077-7749/2014/0407.

Márquez-Aliaga, A., Klein, N., Reolid, M., Plasencia, P., Villena, J. A., & Martínez-Pérez, C. (2019). An enigmatic marine reptile, Hispaniasaurus cranioelongatus (gen. et sp. nov.) with nothosauroid affinities from the Ladinian of the Iberian Range (Spain). Historical Biology, 31(2), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2017.1359264.

Márquez-Aliaga, A., & López-Gómez, J. (1989). Paleontología y ambientes sedimentarios del Triásico medio, Muschelkalk, de la Cordillera Ibérica I: Cuenca y Valencia, España. Estudios Geológicos, 45, 387–398.

Martínez-Delclòs, X. (1995): Plants. Invertebrates. Systematic Paleontology. In: X. Martínez-Delclòs (ed.), II International Symposium on Lithographic Limestones. Montsec and Montral-Alcover. Two Konservat-Lagerstätten, Field trip guide book. Catalonia, Spain (pp. 81–87).

Mathieu, A. (1965). Etudes géologiques dans la région au Sud de Cañete (Cuenca). Diplôme d’étudiant.

Mazin, J. M. (1989). La denture et la region palatine des Placodontia (Reptilia, Trias). Implications phylogénétiques. Geobios, 22, 725–734.

Meyer, H. V. (1839). Mittheilung, an Professor Bronn gerichtet. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geognosie, Geologie und Petrefaktenkunde, 1839, 559–560.

Meyer, H. V. (1842). Simosaurus, die Stumpfschnauze, ein Saurier aus dem Muschelkalke von Luneville. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geognosie, Geologie und Petrefakten-Kunde, 1842, 184–197.

Meyer, H.v., (1858). Psephoderma alpinum aus dem Dachsteinkalke der Alpen. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geognosie, Geologie und Petrefaktenkunde, 1858, 646–650.

Münster, G. (1834). Vorläufige Nachricht über einige neue Reptilien im Muschelkalke von Baiern. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geognosie, Geologie und Petrefaktenkunde, 1834, 521–527.

Navarro-Lorbés, P., Alonso, A., Gil Imaz, A., Canudo, J. I. (2016). First evidence of marine reptiles from the Upper Triassic (Keuper) of Alpartir (Zaragoza, Spain). In F. Torcida Fernández-Baldor, J. I. Canudo, P. Huerta, X. Pereda, (Eds.), Abstract book. VII International Symposium about Dinosaurs Palaeontology and their Environment (pp. 105–106). Salas de los Infantes (Burgos).

Neenan, J. M., Klein, N., & Scheyer, T. M. (2013). European origin of placodont marine reptiles and the evolution of crushing dentition in Placodontia. Nature Communications, 4(1621), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2633.

Neenan, J. M., Li, C., Rieppel, O., & Scheyer, T. M. (2015). The cranial anatomy of Chinese placodonts and the phylogeny of Placodontia (Diapsida: Sauropterygia). Zoological Journal of Linnean Society, 175(2), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12277.

Niemeyer, J. (2002). Invertebraten und Vertebraten aus dem Muschelkalk von Siles (Jaén), Spanien. Münstersche Forschungen zur Geologie und Paläontologie, 94, 1–98.

Nopcsa, F. (1923). Die Familien der Reptilien. In W. Soergel (Ed.), Fortschritte der Geologie und Palaeontologie (Vol. 2, pp. 1–210). Berlin: Borntraeger.

Nopcsa, F. (1928). Palaeontological notes on reptiles. Geologica Hungaria, Ser. Palaeontologica, 1, 3–84.

Nosotti, S., & Rieppel, O. (2003). Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi n. gen n. sp., a new, unusual diapsid reptile from the Middle Triassic of Besano (Lombardy, N Italy). Memorie della Societá Italiana di Scienze Naturali e del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano, 31, 3–33.

Owen, R. (1860). Palaeontology; or, a systematic summary of extinct animals and their geologic remains. Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black.

Pérez-Valera, J. A., Berrocal-Casero, M., & Pérez-Valera, F. (2019). First Triassic tetrapod (Eusauropterygia) in the Triassic of the Subbetic domain of the Betic Cordillera (Southeastern Spain). PalZ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12542-019-00500-y.

Petit, P. (1964). Etude géologique de la région d’Almansa (Albacete). Diplôme d’étudiant.

Peyer, B. (1931a). Paraplacodus broilii nov. gen. nov. sp., ein neuer Placodontier aus der Tessiner Trias. Vorläufige Mitteilung. Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie, B, 1931, 570–573.

Peyer, B. (1931). Die Triasfauna der Tessiner Kalkalpen. IV. Ceresiosaurus calcagnii nov. gen. nov. spec. Abhandltmgen der schweizerischen Paläontologischen Gesellschaft, 51, 1–68.

Pinna, G. (1990). I rettili placodonti dei terreni triassici di Spagna. Atti della Societa Italiana di Scienze Naturali e del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano, 131, 137–143.

Quesada, J. M., de la Fuente, M., Ortega, F., & Sanz, J. L. (1998). Bibliografía del registro español de vertebrados mesozoicos. Boletín de la Real Sociedad Española de Historia Natural (Sección Geología), 94, 101–137.

Quesada, J. M., & Aguera González, S. (2005). Descripción del primer ejemplar de Ceresiosaurus (Reptilia: Sauropterygia), hallado en la Península Ibérica en el Ladiniense (Triásico Medio) de Mont-ral-Alcover (Tarragona). Estudios Geológicos, 61, 247–269. https://doi.org/10.3989/egeol.05613-667.

Quesada, J., Pérez-García, A., Ortega, F., Escaso, F., & Sánchez-Chillón, B. (2009). Simosaurus (Nothosauria) fossil site: A new Spanish window to the Upper Triassic. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 29(3 Abstracts), 168A.

Renesto, S., Binelli, G., & Hagdorn, H. (2014). A new pachypleurosaur from the Middle Triassic Besano Formation of Northern Italy. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen, 271(2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1127/0077-7749/2014/0382.

Reolid, M., Pérez-Valera, F., Benton, M. J., & Reolid, J. (2014). Marine flooding event in continental Triassic facies identified by a nothosaur and placodont bonebed (South Iberian Paleomargin). Facies, 60, 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10347-013-0360-6.

Reolid, M., & Reolid, J. (2020). First record of Triassic marine reptiles (Nothosauria, Sauropterygia) from the Alpujarride Complex (Internal Zones of the Betic Cordillera, Spain). Estudios Geológicos, 76(1), e126. https://doi.org/10.3989/egeol.43592.535.

Rieppel, O. (1994). Osteology of Simosaurus gaillardoti and the relationships of stem-group Sauropterygia. Fieldiana: Geology, 28, 1–85.

Rieppel, O. (1996). The status of the sauropterygian reptile Partanosaurus zitteli Skuphos from the Middle Triassic of the Austrian Alps, with comments on Microleptosaurus schlosseri Skuphos. Palaontologische Zeitschrift, 70, 567–577.

Rieppel, O. (1997). Revision of the Sauropterygian Reptile Genus Cymatosaurus v. Fritsch, 1894, and the Relationships of Germanosaurus Nopcsa, 1928, from the Middle Triassic of Europe. Fieldiana: Geology, 36, 1–38.

Rieppel, O. (1998). The status of the sauropterygian reptile genera Ceresiosaurus, Lariosaurus, and Silvestrosaurus from the Middle Triassic of Europe. Fieldiana: Geology, 38, 1–46.

Rieppel, O. (1999). The sauropterygian genera Chinchenia, Kwangsisaurus, and Sanchiaosaurus from the Lower and Middle Triassic of China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 19(2), 321–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.1999.10011144.

Rieppel, O. (2000a). Part 12A. Sauropterygia I. In P. Wellnhofer (Ed.), Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie (pp. 1–134). München: Verlag Friedrich Pfeil.

Rieppel, O. (2000b). Paraplacodus and the phylogeny of the Placodontia (Reptilia: Sauropterygia. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 130, 635–659. https://doi.org/10.1006/zjls.2000.0232.

Rieppel, O. (2001). The cranial anatomy of Placochelys placodonta Jaekel, 1902, and a review of the Cyamodontoidea (Reptilia, Placodonta). Fieldiana: Geology, 45, 1–101.

Rieppel, O. (2002). The dermal armor of the cyamodontoid placodonts (Reptilia, Sauropterygia): Morphology and systematic value. Fieldiana: Geology, 46, 1–51.

Rieppel, O., & Hagdorn, H. (1998). Fossil reptiles from the Spanish Muschelkalk (Mont-ral and Alcover, Province Tarragona). Historical Biology, 13, 77–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912969809386575.

Rieppel, O., & Werneburg, R. (1998). A new species of the sauropterygian Cymatosaurus from the Lower Muschelkalk of Thuringia, Germany. Palaeontology, 41(4), 575–589.

Rieppel, O., Mazin, J. M., & Tchernov, E. (1999). Sauropterygia from the Middle Triassic of Makhtesh Ramon, Negev, Israel. Fieldiana: Geology, 40, 1–85.

Rieppel, O., Sander, P. M., & Storrs, G. W. (2002). The skull of the pistosaur Augustasaurus from the Middle Triassic of northwestern Nevada. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 22(3), 577–592. https://doi.org/10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0577:TSOTPA]2.0.CO;2.

Romer, A. S. (1956). The osteology of the reptiles. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

San, K. K., Fraser, N. C., Foffa, D., Rieppel, O., & Brusatte, S. L. (2019). The first Triassic vertebrate fossils from Myanmar: Pachypleurosaurs in a marine limestone. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 64(2), 357–436. https://doi.org/10.4202/app.00594.2019.

Sander, P. M., Rieppel, O., & Bucher, H. (1997). A new pistosaurid (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Middle Triassic of Nevada and its implications for the origin of the plesiosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 17(3), 526–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.1997.10010999.

Sander, P. M., Klein, N., Albers, P. C. H., Bickelmann, C., & Winkelhorst, H. (2014). Postcranial morphology of a basal Pistosauroidea (Sauropterygia) from the Lower Muschelkalk of Winterswijk, The Netherlands. Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 88, 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12542-013-0181-5.

Sanz, J. L. (1976). Lariosaurus balsami (Sauropterygia, Reptilia) de Estada (Huesca). Estudios Geológicos, 32, 547–567.

Sanz, J. L. (1980). Los notosaurios españoles. Análisis filogenético y sistemático de los sauropterigios triásicos. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid.

Sanz, J. L. (1983). Los notosaurios (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) españoles. Estudios Geológicos, 39, 193–215.

Sanz, J. L. (1991). Notosaurios y placodontos (Reptilia). Su registro en el yacimiento de Bienservida-Villarrodrigo. In Actas de las Jornadas sobre el Medio Natural Albacetense, Albacete (pp. 17–32).

Sanz, J. L., Alafont, L. S., & Moratalla, J. J. (1993). Triassic reptile faunas from Spain. Paleontologia Lombarda della Societá di Scienze Naturali del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano, II, 153–164.

Sato, T., Cheng, Y.-N., Wu, X.-C., & Li, C. (2010). Osteology of Yunguisaurus Cheng et al., 2006 (Reptilia; Sauropterygia), a Triassic Pistosauroid from China. Paleontological Research, 14(3), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.2517/1342-8144-14.3.179.

Sato, T., Zhao, L.-J., Wu, X.-C., & Li, C. (2014). A new specimen of the Triassic pistosauroid Yunguisaurus, with implications for the origin of Plesiosauria (Reptilia, Sauropterygia). Palaeontology, 57(1), 55–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/pala.12048.

Scheyer, T. M., Neenan, J. M., Bodogan, T., Furrer, H., Obrist, C., & Plamondon, M. (2017). A new, exceptionally preserved juvenile specimen of Eusaurosphargis dalsassoi (Diapsida) and implications for Mesozoic marine diapsid phylogeny. Scientific Reports, 7, 4406. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04514-x.

Shang, Q.-H., Sato, T., Li, C., & Wu, X.-C. (2017). New osteological information from ‘juvenile’ specimen of Yunguisaurus (Sauropterygia; Pistosauroidea). Palaeoworld, 26(3), 500–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palwor.2016.05.008.

Shang, Q.-H., Li, C., & Wu, X.-C. (2017). New information on Dianmeisaurus gracilis Shang & Li 2015. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 55(2), 145–161.

Sues, H.-D. (1987). Postcranial skeleton of Pistosaurus and interrelationships of the Sauropterygia (Diapsida). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 90, 109–131.

Storrs, G. W. (1991). Anatomy and relationships of Corosaurus alcovensis (Diapsida: Sauropterygia) and the Triassic Alcova Limestone of Wyoming. Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History Yale University, 44, 1–151.

Stubbs, T. L., & Benton, M. J. (2016). Ecomorphological diversifications of Mesozoic marine reptiles: the roles of ecological opportunity and extinction. Paleobiology. https://doi.org/10.1017/pab.2016.15. (published online).

Via Boada, L., Villalta, J. F., & Esteban Cerdá, M. (1977). Paleontología y paleoecología de los yacimientos fosilíferos del Muschelkalk superior entre Alcover y Mont-ral (Montañas de Prades, provincia de Tarragona). Cuadernos Geología Ibérica, 4, 247–256.

Vickers-Rich, P., Rich, T. H., Rieppel, O., Thulborn, R. A., & McClure, H. A. (1999). A Middle Triassic vertebrate fauna from the Jilh Formation, Saudi Arabia. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie Abhandlungen, 213, 201–232.

Vincent, P., Bardet, N., Bouya, B., Amaghzaz, M., & Meslouh, S. (2011). Zarafasaura oceanis, a new elasmosaurid (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Maastrichtian: Sauropterygia) from the Maastrichtian Phosphates of Morocco and the palaeobiogeography of latest Cretaceous plesiosaurs. Gondwana Research, 19, 1062–1073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2010.10.005.

Wang, W., Ma, F., & Li, C. (2019). First subadult specimen of Psephochelys polyosteoderma (Sauropterygia, Placodontia) implies turtle-like fusion pattern of the carapace. Papers in Palaeontology. https://doi.org/10.1002/spp2.1293.

Wang, W., Li, C., & Wu, X.-C. (2019). An adult specimen of Sinocyamodus xinpuensis (Sauropterygia: Placodontia) from Guanling, Guizhou, China. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 185(3), 910–924. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zly080.

Wang, W., Li, C., Scheyer, T. M., & Zhao, L. (2019). A new species of Cyamodus (Placodontia, Sauropterygia) from the early Late Triassic of south-west China. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 17, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14772019.2018.1535455.

Westphal, F. (1975). Bauprinzipien im Panzer der Placodonten (Reptilia triadica). Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 49, 97–125.

Wintrich, T., Hayashi, S., Houssaye, A., Nakajima, Y., & Sander, P. M. (2017). A Triassic plesiosaurian skeleton and bone histology inform on evolution of a unique body plan. Science Advances, 3, e1701144. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1701144.

Zhao, L. J., Li, C., Liu, J., & He, T. (2008). A new armored placodont from the Middle Triassic of Yunnan Province, southwestern China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 46, 171–177.

Acknowledgements