Abstract

It is well known that the self-employed are over-represented at the bottom as well as the top of the income distribution. This paper shifts the focus from the income situation of the self-employed to the distributive effects of a change in self-employment rates. With representative German data and unconditional quantile regression analysis we show that an increase in the proportion of self-employed individuals in the labor force increases income polarization by tearing down floors at the bottom and allowing higher income potentials at the very top of the hourly income distribution. Recentered influence function regression of inequality measures corroborate that self-employment is a source of income inequality in the labor market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Aghion et al. (2019) have shown that entrepreneurial income is over-represented relative to wage income among the top 1% incomes in the United States. In addition, there are many narratives about successful entrepreneurs and therefore one might conclude that entrepreneurship creates substantial potentials to become extremely wealthy. As these successful entrepreneurs also generate new jobs, active labor market policy frequently aims at fostering self-employment or entrepreneurship, respectively. Despite the considerable wealth enhancing potentials of entrepreneurship, it has become common knowledge that many self-employed earn less than paid employees (Hamilton 2000; Levine and Rubinstein 2017). The self-employed hence are not just over-represented at the upper tail of the income distribution, but also at the bottom (Astebro et al. 2011). One might therefore hypothesize that an increase in self-employment might contribute to income polarization by widening the top of the income distribution, but also by extending the bottom of the distribution (see Halvarsson et al. 2018).Footnote 1

Entrepreneurship is usually associated with low profits and high risks (Hamilton 2000; Moskowitz and Vissing-Jorgensen 2002). The seminal literature in that field (Hamilton 2000), however, considered the self-employed as a rather homogeneous group and therefore examined self-employed as a whole. More recent studies identified heterogeneous types of entrepreneurs and revealed distinct income differences for these groups. In the German context, Sorgner et al. (2017) have shown that especially the self-employed with employees (employers) manage to achieve higher hourly incomes than paid employees. Self-employed individuals without any employees (solo self-employed) in turn usually are worse off. In addition, it has been shown that hourly incomes of both, solo self-employed as well as employers are more dispersed than the ones of paid employees. This basically reflects business opportunities and risks associated with self-employment. The descriptive statistics presented in Halvarsson et al. (2018) also reveal that the variation of market incomes is higher among the incorporated self-employed as well as the self-employed in a private business (sole proprietorship) than among the workers in Sweden. With U.S. data, Levine and Rubinstein (2017) show that incomes of incorporated as well as unincorporated self-employed are more dispersed than earnings of salaried workers with comparable traits. This higher income variation of the self-employed might also lead to higher income inequality (García-Peñalosa and Orgiazzi 2013). We contribute to this ongoing debate by examining whether and how an increase in employers or solo self-employed individuals affects the income distribution.Footnote 2

Ritzen and Zimmermann (2018) have shown that inequality in the U.S. is one recent factor associated with a decline in optimism about future life. For this reason, factors shaping inequality might also affect confidence in the future, societal stability, and economic development. Yet little is known about the effects of increasing self-employment rates on the distribution of incomes and income inequality, respectively. An exception is the paper by Atems and Shand (2018), who show with U.S. state-level data that entrepreneurship and income inequality are positively correlated. In this line, we show that countries with higher self-employment rates tend to be more unequal (see Fig. 1), where the mechanisms behind this pattern are still largely unclear. For this reason, we analyze the distributive effects of increasing self-employment rates and ask whether a higher share of self-employed individuals is associated with advantageous income effects at the top of the income distribution and adverse effects at the bottom of the income distribution. Both distinctive effects ultimately reinforce income polarization and income inequality.

Most studies on income differences between paid employees and the self-employed apply conditional quantile regression. However, this procedure usually does not allow conclusions about treatment effects on unconditional quantiles, but allows for statements about the income distribution as a whole. Political interest, in turn, usually focuses on the question how a change in self-employment rates alters the unconditional income distribution or the distributive effects, respectively. We therefore address the effect of an increase in the self-employment rate on the hourly income distribution by utilization of the unconditional quantile regression approach and utilize recentered influence function (RIF) regression (Firpo et al. 2009). In addition, this methodology is applied to examine whether changes in self-employment also affect income inequality.

With representative German data of the year 2015, we corroborate that the self-employed are over-represented at the bottom as well as at the top of the hourly income distribution. The RIF regression results reveal that a rise in self-employment rates significantly increases income inequality. This effect is due to income polarization. Precisely, an increase in the share of self-employed is associated with adverse effects at the bottom of the income distribution as well as advantageous effects at the top. While the effect at the bottom is mainly driven by solo self-employed, the increase of hourly incomes among the top earners is mainly due to self-employed with employees.

2 Data and variables

We use the German Socio-Economic Panel-version 32 (SOEP, https://doi.org/10.5684/soep.v32). The SOEP is a longitudinal survey of more than 10 thousand private households in Germany and is provided by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) Berlin. Basic data characteristics are described in Wagner et al. (2007) or Goebel et al. (2018). The SOEP contains variables about demography, employment as well as the household. Note that in Germany, also other representative data sets are available. Recently, Sorgner et al. (2017) utilized the German Micro-Census in their study comparing incomes of self-employed and earnings of paid employees. This data set surveys monthly individual incomes in 24 groups of uneven size. Categories thereby range from 0–150 Euro to more than 18,000 Euro. In the SOEP, in turn, income is reported on a cardinal scale. The SOEP is therefore preferable because uneven categorization and right censoring in the Micro-Census would restrict our analysis of income inequality in a very sensitive way.

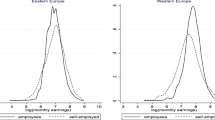

The dependent variable in our analysis is the hourly gross income. Precisely, the surveyed gross income achieved in the month before the interview is used as central measure of income, which is then normalized by the actual work time . In fact, the survey contains the weekly work time. This variable is therefore multiplied with the factor 4.29Footnote 3 to conclude about the monthly working hours. Our central variable of interest describes the employment status of respondents. In fact, individuals are asked to report whether they are paid employees or self-employed with or without employees.Footnote 4 Germany experienced a rise in self-employment levels, which was mainly driven by an increase in solo self-employment (Brenke 2013; Fritsch et al. 2015; Maier and Ivanov 2018). According to Metzger (2015), 58.6% of full-time founders in year 2015 can be classified as solo entrepreneurs. We therefore concentrate on self-employed without any employees and those with employees. Note that the hourly income distribution differs distinctively by occupational status (see Fig. 2 and Sorgner et al. 2017). As both groups of self-employed individuals are disproportionately common at the tails of the distribution, this distinction might help to assess the impact of self-employment on the income distribution more accurately.

The SOEP includes information on demographics as well as employment history and household composition. In this study, a comprehensive set of control variables is included. These comprise age (squared), sex, nationality (German/non-German), marital status (married/single/other), children under 16 years in household (yes/no), and a regional indicator giving insights about the federal state, the respondent is living in. Also the educational level is accounted for by dummy variables (primary education or a lower secondary degree/upper secondary degree/tertiary degree) to address income differences due to qualification levels. Human capital indicators, such as the labor market experience in part-time jobs as well as in full-time jobs (measured in years) and years in unemployment are also controlled for. We additionally control for tenure (in years): For the self-employed, it reveals experience in the current self-employed work, while for employees, it describes the time at the current employer. For this reason, tenure is capable to capture the income effects associated with early or later stages of self-employment. Finally, we include dummy variables to control for the occupation via the German classification of occupations 2010 (KldB10), which is closely related to the International Standard Classification of Occupations 2008 (ISCO-08). Precisely, we generate dummy variables in accordance with the corresponding 3-digit codes. This allows to account for a maximum of 144 groups of jobs according to the tasks and duties undertaken in the job. Descriptive statistics on the variables included in the analysis are presented in Table 3 in the Appendix.

In line with the tradition of studies applying conditional quantile regression approaches, we conduct cross-sectional analysis (Sorgner et al. 2017). In fact, the latest year of the underlying SOEP version, that is year 2015, is considered. The analysis is restricted to individuals who report to be full-time employed. Also note that the analysis does not account for civil servants as the relation between gross and net incomes is distinctively different from other employees and the self-employed. Finally, the analysis is restricted to individuals aged between 19 and 65 years.

3 Methodology

Conditional quantile regression helps to understand the impact of covariates along the distribution of an outcome. Application of this approach acknowledges that different characteristics might exhibit a different impact among low- and high-income earners. For this reason, the methodology is so popular in economic studies, which assess the impact of a variable on a quantile/percentile of the outcome (conditional on other variables). This approach also has been applied a magnitude of studies analyzing the income of self-employed in comparison to paid employees (among others Hamilton 2000; Sorgner et al. 2017). Potentially heterogeneous effects, as in the case of self-employment, where self-employed at the bottom (top) are worse (better) off than employees, however, do not imply that an increase in self-employment has a stronger effect for the low (high) income earners, but for the conditionally low (high) income earners. Therefore, the results do not necessarily suggest that the unconditional income distribution is more disperse.

Quantile regression is a powerful method to examine the effects of self-employment on the conditional distribution of incomes. The political interest, however, mostly lies in how shifting self-employment rates alter the distributive effects. Such questions can be addressed by estimation of an unconditional quantile approach. The unconditional distribution can be thought of the product of the conditional distribution of income on self-employment and the marginal distribution of self-employment (Alejo et al. 2014). The effect of an increase in self-employment therefore depends on the interaction between the marginal distribution of self-employment as well as the conditional distribution of income. As pointed out by Alejo et al. (2014), the step from conditional to unconditional distributive effects is not trivial and the unconditional quantile regression approach based on the concept of the RIF seems to be an important step towards this goal. The RIF approach is based on the properties of the influence function (Firpo et al. 2009), which is used in the robust statistics literature (Hampel et al. 1986). The influence function is an analytical tool used to examine the effect or influence of adding an observation on the value of a statistic (\(\nu (F_{Y})\)) without the need to recalculate the particular statistic ( Borah and Basu 2013). In general, the RIF is defined as shown in equation (1). It contains the influence function (IF) and a functional of interest, which is utilized to recenter the influence function (\(\nu (F_{Y})\)). Y describes a random variable with cumulative distribution function \(F_Y(y)\). In our case, Y describes the hourly income.

Firpo et al. (2009) have shown that a RIF regression can be viewed as an unconditional quantile regression approach when the conditional expectation of \(RIF(y ; \,q_{\tau })\)Footnote 5 is modeled as a function of explanatory variables. Hence, after computing the functional of the RIF for the specific percentile of interest, we estimate a regression with covariates. The resulting coefficients can be interpreted, ceteris paribus, as the marginal effect of a small shift in the distribution of covariates on the specific unconditional percentile.

The RIF regression approach is also adequate to measure inequality. For example, IFs are available for the variance, the Gini coefficient, or other measures of inequality. Hence, one might use these IFs and run RIF regressions (see Choe and Van Kerm 2018; Firpo et al. 2018). In this paper, we start with an examination of the effect of a rise in self-employment on the variance of the hourly income. A higher variance is indicative of higher deviations from the mean and therefore higher inequality. We, moreover, apply the Gini index, the general entropy index as well as the Atkinson inequality measure, whereas all are prominent measures of wealth and income inequality (Cowell and Van Kerm 2015). The Gini index is utilized because it is one of the most popular measures in research on inequality. It ranges between zero and one, whereas one describes perfect inequality. As one might expect distinctive results at the bottom as well as at the top of the income distribution (Halvarsson et al. 2018), we also apply inequality measures, which are sensitive to changes at different parts of the hourly income distribution. In this regard, we calculate the RIFs for two general entropy measures, whereas the Theil index is more sensitive to differences at the top of the hourly income distribution than the mean log deviation. Finally, the Atkinson index allows to alter in which part changes of the income distribution will be most sensitive by changing \(\epsilon \). Higher \(\epsilon \) implies rising sensitivity to changes at the bottom of the distribution. All the inequality measures have in common that higher values represent a higher level of inequality. Hence, estimation of a positive coefficient in the RIF regression is associated with a higher level of inequality.

4 Results

This section presents the central results. Linear regression reveals that the self-employed indeed obtain higher average hourly income than paid employees (Table 4, Specification (1)). In fact, the average markup equals 3.64 Euros or 19.65% (\(=\frac{3.64}{18.52}*100\%\)), respectively. This is in line with the common knowledge that self-employed obtain higher average incomes than paid employees.Footnote 6 This positive effect, however, is essentially driven by the employers (Table 4, Specification (2)), while average hourly incomes of solo self-employed and paid employees are rather similar.Footnote 7 These results show that it is important to distinguish between the solo self-employed and the employers.

Now, we shift the focus to the political view and address the question how an increase in self-employment rates changes the income distribution. This question is addressed by application of the RIF regression approach. Precisely, we examine the effect of an increase in self-employment on income inequality by application of a variety of different RIF regressions of inequality measures.Footnote 8 All RIF regressions presented in Panel A of Table 1 are in line with an inequality enhancing effect of self-employment. A more differentiated view suggests that an increase in self-employed without employees has a positive, but statistically insignificant effect on the variance of hourly incomes, while an increase in the rate of employers is suggested to increase wage dispersion (Table 1, Panel B). Estimation of the RIF regression with respect to the Gini index implies that an increase in the rate of both types of self-employment leads to a rise in inequality (specification (2)). The effect for employers, however, is three times larger when compared to the one for the solo self-employed. Also the estimates based on the general entropy measures shown in specifications (3) and (4) corroborate that an increase in self-employment significantly contributes to income inequality. Finally, the estimated coefficients regarding the Atkinson inequality measures are presented in specifications (5)–(7). The coefficients of both groups of self-employed increase with rising \(\epsilon \). This also holds for the relative effects of the solo self-employed. The relative effects of employers, in contrast decrease with increasing \(\epsilon \). This corroborates that solo self-employment is likely to introduce inequality by shifting the bottom incomes, while employers are likely to increase inequality at the top of the income distribution.

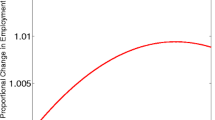

The results shown in Table 1 clearly suggest that self-employment is a source of income inequality in the labor market. To conclude about the mechanisms, which cause increasing income inequality, we also apply unconditional quantile regression for each decile. On the one hand, an increase in self-employment rates shifts the hourly income distribution to left until the 6th decile (see Table 2, Panel A). The effects, however, are statistically significant up to decile 5. On the other hand, a rise in self-employment rates also contributes to significantly rising incomes for the top 20% of the income distribution. Self-employment thus is suggested to be a source of income polarization.

Our estimates presented in Panel B of Table 2 suggest that adverse effects are more pronounced among the solo self-employed. An increase in solo self-employment shifts the hourly income distribution to the left until the 7th decile. As the effect is statistically significant until the 6th decile, an increase in solo self-employment decreases the hourly incomes significantly at least for the bottom 60% of the distribution. More specifically, the coefficient of -3.1743 in specification (1) implies that an increase in solo self-employment from 4.39% to 5.39% reduces incomes in the lowest decile by about 0.3631% (\(=\frac{-0.031743}{8.7413}*100\%\)). This economically meaningful effect seems plausible because self-employed face business risks and are not subject to (hourly) minimum wages or incomes, respectively. As the effect is statistically significant as well as economically relevant, we conclude that the effects of an increase in solo self-employment exhibits considerable adverse effects for the bottom 10% of the full-time workforce. In the fifth decile, the corresponding effect of a one percentage point increase in solo self-employment reduces hourly income by about 0.1002% (\(=\frac{0.015766}{15.7343}*100\%\)). Specification (9) in Table 2 also adverts to positive effects for the top 10% of earners. The estimated effect of an increase in the share of solo self-employed, however, is only of weak statistical significance.

An increase in the share of employers exhibits statistically significant negative effects on hourly incomes for the bottom 30% of the distribution. In combination with the results for the solo self-employed, a rise in self-employment seems to tear down floors at the very bottom of the hourly income distribution. A rising share of employers, however, also exhibits positive income effects and significantly shifts the income distribution for earners above the 6th decile to the right. When the share of employers increases by one percentage point, hourly incomes among the top 10% are estimated to increase by 0.3099% (\(=\frac{0.096314}{31.0800}*100\%\)).

We also checked the robustness of our results. Although we control for working time and all individuals reported to be full-time employed, 225 individuals declared to work for less than 35 hours per week. We therefore examined whether our results are robust to considering individuals with working hours of at least 35 hours per week. The final sample consists of 7,722 individuals (309 solo self-employed and 364 employers). The results of the RIF regression analysis for inequality are presented in Table 5. The coefficients are qualitatively robust to the ones shown in Table 1. With respect to polarization (see Table 6), the results are robust as well.

5 Discussion and avenues for future research

In this section, we discuss our main results and also hope to stimulate further research. In the past, Germany experienced a rise in solo self-employment (Brenke 2013; Fritsch et al. 2015; Maier and Ivanov 2018). In this context, the results might be suggestive that the increase in self-employment was largely due to entry into the bottom of the hourly income distribution. Therefore, a promising avenue for future research is the analysis of occupational choice. In this regard, the literature has found for instance that entrepreneurs face finance and liquidity constraints (Blanchflower and Oswald 1998). When we assume that the quality of a business is positively correlated with start-up costs, then initial wealth inequality may be a reason for long tails in the income distribution of entrepreneurs because one might imagine that only the richer households can gain access to the good opportunities. We therefore encourage studies, which explicitly account for individual financial constraints. In addition, one might also study whether and how (private) start-up financing might help dampening adverse effects associated with occupational choice, liquidity constraints, and initial wealth inequality.

This paper, moreover, contributes to the literature on active labor market policy aiming at rising the self-responsiveness and fostering self-employment out of unemployment. In fact, most of subsidized start-ups are created by single founders or solo entrepreneurs, respectively. This particular group is also likely to remain in the state of solo self-employment (Caliendo et al. 2012).Footnote 9 Based on our results, policy interventions fostering entrepreneurship might have unintended consequences on the income distribution because subsistence entrepreneurship tears down floors at the bottom of the income distribution and also increases inequality. As our analysis does not directly account for individual start-up subsidies, we encourage studies on the consequences of active labor market policy fostering entrepreneurship with respect to effects on the income distribution. Future research might also study whether increasing inequality induces unintended effects on the entrepreneurial ecosystem or causes spillover effects on politics or health.

Finally, note that the results can also be interpreted in a different way. In fact, lower self-employment rates are suggestive of decreasing income polarization. However, although entrepreneurship might be an amplifier of inequality, researchers suggest that entrepreneurship and start-up activity should not be discouraged because ”venture creation still grows the pie—perhaps just not toward a more even distribution” (Frid et al. 2016, p. 918).Footnote 10 Nevertheless, one might try to dampen the effects at the very bottom of the distribution. In this regard, it must be highlighted that policy fostering entrepreneurship ”is not a numbers game. It is about encouraging the formation of high quality [...] companies” (Shane 2009, p. 141).

6 Conclusion

This paper contributes to the literature in three distinctive ways: At first, we examine the income situation of self-employed in comparison to paid employees. Second, we study the effects of a change in the rate of self-employment on income inequality. Finally, we investigate the role of self-employment with regard to income polarization. The empirical analysis is based on the German SOEP data set with reference to survey year 2015 . With respect to the fist point, we confirm prior findings that many self-employed are worse off when compared to paid employees (e.g., Hamilton 2000). The pattern, however, becomes more differentiated when we distinguish between solo self-employed and self-employed who also managed to create jobs for others. Specifically, we show that especially the solo self-employed obtain lower hourly incomes than paid employees and employers. Employers, in turn, are likely to be among the top income earners. This result basically corroborates that the self-employed are over-represented at the bottom as well as at the top of the income distribution (Astebro et al. 2011).

Besides the income situation of the self-employed, we also analyzed whether and how an increase in self-employment affects the hourly income distribution. RIF regressions of inequality measures highlight the income inequalizing power of a rise in self-employment rates. We thereby corroborate the very recent findings presented in Halvarsson et al. (2018) who showed that entrepreneurship indeed affects overall workforce income inequality in Sweden. More specifically, Halvarsson et al. (2018) showed that self-employed in sole proprietorships increase inequality by widening the bottom of the income distribution. Self-employed in incorporated businesses mainly increase the number of high-income earners and therefore enhance inequality by widening the top of the distribution. With German data, we basically confirm this pattern by distinguishing between solo self-employed and employers.

Our paper extends the literature by showing that a rise in self-employment contributes to income inequality by income polarization. Precisely, the RIF regression results suggest that an increase in solo self-employment reduces hourly incomes for the bottom 60% of the considered workforce. An increase in self-employed with employees, in turn, shifts the hourly income distribution for the high income earners to the right and therefore rises the top-incomes. To conclude, income inequality is reinforced by tearing down floors at the bottom and by widening the top of the income distribution.

Notes

Note that Halvarsson et al. (2018) provide an excellent survey of the literature on entrepreneurship, income dynamics, and inequality.

Empirical studies with German data mostly differ between employers and solo self-employed (Lechmann and Wunder 2017; Sorgner et al. 2017) because information on whether a business is incorporated is usually not available. International studies use this particular distinction as well (Van Stel et al. 2014).

30 days per month divided by 7 days per week.

Freelancers are defined as self-employed as well. Our final sample consists of 480 individuals reporting to be self-employed and 246 freelancers.

\(q_{\tau }\) stands for the hourly income at the quantile of interest (\(\tau \)).

Note that the set of control variables includes 140 dummy variables in accordance with the classification of occupations (KldB10), which describe tasks of a job. This ultimately allows interpretation of the effects as income differentials between self-employed and paid employees in similar jobs.

There is a discussion about comparability of incomes from self-employment and wages of paid employees (Lechmann 2015). Moreover, potential misreporting of incomes from self-employment are debated in the literature (Astebro and Chen 2014). In fact, Astebro and Chen (2014) showed that there is a sizable mean financial gain of entrepreneurship after correcting for misreporting. However, the correction methods heavily rely on the underlying assumptions, which can be ”unpalatable” (Astebro and Chen 2014). In our case, we already observe a meaningful average financial markup for the self-employed (see specification (1) in Table 4). In addition the median income of the self-employed is slightly smaller than the one of paid employees (see specification (3) in Table 4), which indicates that the median self-employed obtains slightly lower hourly incomes when compared with a paid employee with identical characteristics. Hence, systematic income under- or misreporting by the self-employed seems to be no problem in our study.

We are indebted to Philippe Van Kerm for sharing his STATA code to run the command inequaly, which helps to predict a variety of RIFs of a variable (Van Kerm 2015). Precisely, we applied his code for calculation of the RIF of the general entropy index as well as the Atkinson inequality measure.

Caliendo et al. (2012) showed that about 70% of surviving subsidized business founders did not become employers 19 months after the start-up. This pattern is not restricted to subsidized founders. Lechmann and Wunder (2017) found that it is rather unlikely for solo self-employed to become employers. Also other studies showed that the majority of entrepreneurs has low growth ambitions (Hurst and Pugsley 2011) and that entrepreneurship is frequently small scaled rather than taking the form of growing productive and prospering firms (Schoar 2010; Stam 2013).

See Frid et al. (2016) for a discussion of the relationship between entrepreneurship and wealth inequality.

References

Aghion, P., Akcigit, U., Bergeaud, A., Blundell, R., & Hemous, D. (2019). Innovation and top income inequality. The Review of Economic Studies, 86(1), 1–45.

Alejo, J., Gabrielli, M. F., & Sosa-Escudero, W. (2014). The distributive effects of education: An unconditional quantile regression approach. Revista de Analisis Economico - Economic Analysis Review, 29(1), 53–76.

Astebro, T., & Chen, J. (2014). The entrepreneurial earnings puzzle: Mismeasurement or real? Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 88–105.

Astebro, T., Chen, J., & Thompson, P. (2011). Stars and misfits: Self-employment and labor market frictions. Management Science, 57(11), 1999–2017.

Atems, B., & Shand, G. (2018). An empirical analysis of the relationship between entrepreneurship and income inequality. Small Business Economics, 51(4), 905–922.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (1998). What makes an entrepreneur? Journal of Labor Economics, 16(1), 26–60.

Borah, B. J., & Basu, A. (2013). Highlighting differences between conditional and unconditional quantile regression approaches through an application to assess medication adherence. Health Economics, 22(9), 1052–1070.

Brenke, K. (2013). Allein tätige Selbständige: Starkes Beschäftigungswachstum, oft nur geringe Einkommen. DIW Wochenbericht, 80(7), 3–16.

Caliendo, M., Hogenacker, J., Künn, S., & Wießner, F. (2012). Alte Idee, neues Programm: Der Gründungszuschuss als Nachfolger von Überbrückungsgeld und Ich-AG. Journal for Labour Market Research, 45(2), 99–123.

Choe, C., & Van Kerm, P. (2018). Foreign workers and the wage distribution: What does the influence function reveal? Econometrics, 6(3), 1–26.

Cowell, F. A., & Van Kerm, P. (2015). Wealth inequality: A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 29(4), 671–710.

Firpo, S., Fortin, N. M., & Lemieux, T. (2009). Unconditional quantile regressions. Econometrica, 77(3), 953–973.

Firpo, S. P., Fortin, N. M., & Lemieux, T. (2018). Decomposing wage distributions using recentered influence function regressions. Econometrics, 6(2), 1–40.

Frid, C. J., Wyman, D. M., & Coffey, B. (2016). Effects of wealth inequality on entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 47(4), 895–920.

Fritsch, M., Kritikos, A. S., & Sorgner, A. (2015). Why did self-employment increase so strongly in germany? Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 27(5–6), 307–333.

García-Peñalosa, C., & Orgiazzi, E. (2013). Factor components of inequality: A cross-country study. Review of Income and Wealth, 59(4), 689–727.

Goebel, J., Grabka, M. M., Liebig, S., Kroh, M., Richter, D., Schröder, C., & Schupp, J. (2018). The german socio-economic panel (soep). Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik / Journal of Economics and Statistics.

Halvarsson, D., Korpi, M., & Wennberg, K. (2018). Entrepreneurship and income inequality. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 145, 275–293.

Hamilton, B. H. (2000). Does entrepreneurship pay? an empirical analysis of the returns to self-employment. Journal of Political Economy, 108(3), 604–631.

Hampel, F. R., Ronchetti, E. M., Rousseeuw, P. J., & Stahel, W. A. (1986). Robust statistics: The approach based on influence functions. New York: Wiley.

Hurst, E., & Pugsley, B. W. (2011). What do small businesses do? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 43(2), 73–142.

Lechmann, D. S. (2015). Can working conditions explain the return-to-entrepreneurship puzzle? Journal for Labour Market Research, 48(4), 271–286.

Lechmann, D. S., & Wunder, C. (2017). The dynamics of solo self-employment: Persistence and transition to employership. Labour Economics, 49, 95–105.

Levine, R., & Rubinstein, Y. (2017). Smart and illicit: Who becomes an entrepreneur and do they earn more? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(2), 963–1018.

Maier, M.F., & Ivanov, B. (2018). Selbstständige Erwerbstätigkeit in Deutschland. Forschungsbericht 514. The German Federal Ministry for Labour and Social Affairs (BMAS).

Metzger, G. (2015). KfW-Gründungsmonitor 2015. KfW Bankengruppe, Frankfurt a. M.: Tabellen- und Methodenband. Technical report.

Moskowitz, T. J., & Vissing-Jorgensen, A. (2002). The returns to entrepreneurial investment: A private equity premium puzzle? The American Economic Review, 92(4), 745–778.

Ritzen, J., & Zimmermann, K. F. (2018). Fading hope and the rise in inequality in the united states. Eurasian Business Review, 8(1), 1–12.

Schoar, A. (2010). The Divide between Subsistence and Transformational Entrepreneurship. In Innovation Policy and the Economy, Vol. 10, PP. 57–81. University of Chicago Press.

Shane, S. (2009). Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad public policy. Small Business Economics, 33(2), 141–149.

Sorgner, A., Fritsch, M., & Kritikos, A. (2017). Do entrepreneurs really earn less? Small Business Economics, 49(2), 251–272.

Stam, E. (2013). Knowledge and entrepreneurial employees: A country-level analysis. Small Business Economics, 41(4), 887–898.

Van Stel, A., Wennekers, S., & Scholman, G. (2014). Solo self-employed versus employer entrepreneurs: Determinants and macro-economic effects in oecd countries. Eurasian Business Review, 4(1), 107–136.

Van Kerm, P. (2015). Influence functions at work. In United Kingdom Stata Users’ Group Meetings 2015, Stata Users Group.

Wagner, G. G., Frick, J. R., & Schupp, J. (2007). The german socio-economic panel study (soep)—scope, evolution and enhancements. Schmollers Jahrbuch: Journal of Applied Social Science Studies, 127(1), 139–169.

Acknowledgements

I have benefited from comments by Olaf Hübler, Daniel Lechmann, Wim Naudé, Konrad Schäfer, and participants at the 28th EBES conference in Coventry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This study is based on The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP, https://doi.org/10.5684/soep.v32) from the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin). The author’s program codes will be provided upon request. Any errors are my own. The author has no relevant or material financial interests that relate to the research described in this paper.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schneck, S. Self-employment as a source of income inequality. Eurasian Bus Rev 10, 45–64 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-019-00143-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-019-00143-8