Abstract

We estimate an extended version of the three-equation model of Carree et al. (Small Bus Econ 19(3):271–290, 2002) where deviations from the ‘equilibrium’ rate of self-employment play a central role determining both the growth of self-employment and the rate of economic growth. In particular, we distinguish between solo self-employed and employer entrepreneurs, and allow for different ‘equilibrium’ relationships of these two types of independent entrepreneurship with the level of economic development. In addition, we also allow for different economic growth penalties of deviating from the ‘equilibrium’ rate for these two types. Using data for 26 OECD countries over the period 1992–2008, we find that the ‘equilibrium’ rate of solo self-employment seems to be independent of the level of economic development, whereas the ‘equilibrium’ rate of employer entrepreneurship is negatively related to economic development. Regarding the impact of deviating from the ‘equilibrium’ solo self-employment rate, we find that both positive and negative deviations diminish economic growth. For employer entrepreneurship we do not find such a growth penalty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Several publications have highlighted the likelihood of a two-way relationship between independent entrepreneurship and economic development (Carree et al. 2002; Hartog et al. 2010). First, the level of economic development has a profound effect on the prevalence of business ownership (and on the rate of new business start-ups) through its influence on various determinants of entrepreneurship at both the demand side and the supply side (for a review of the literature see Wennekers et al. 2010). Some examples of such intermediate mechanisms are sector structure, scale economies and occupational choice. In addition, there are empirical grounds for assuming a ‘natural’ or ‘equilibrium’ rate of independent entrepreneurship, related to the level of economic development in a U-shaped, L-shaped, or linearly decreasing manner (Carree et al. 2002; Wennekers et al. 2005).

Secondly, in several studies the potential importance of entrepreneurship for economic progress has also come to the fore (for a review of the literature see Van Praag and Versloot 2008; Carree and Thurik 2010). In one particular study, it has been found that deviations between the actual and the ‘natural’ or ‘equilibrium’ rate of self-employment are negatively related to subsequent macro-economic growth, implying that economies can have too few but also too many self-employed (Carree et al. 2002). In the first regime, levels of competition and dynamism are low, so that businesses do not have enough incentives to innovate and enhance consumer welfare. In the second regime, many firms operate below the minimum efficient scale so that economies of scale remain unexploited. Both situations are suboptimal in terms of achieving high macro-economic growth rates.

Although the above observations apply to self-employment in general, it is also well-known that the self-employed are a very heterogeneous labor market category (Gartner 1985). A specific group that has become more prominent in many modern economies are the so-called own account workers or solo self-employed (self-employed without personnel), who are sometimes also labeled freelancers (Burke 2011). Compared to employer entrepreneurs (self-employed with personnel, mostly in micro and small businesses), their motivations to start up as well as their economic role are thought to be different. The prime goal of the present paper is to investigate the latter aspects of solo self-employment and employer entrepreneurship within the context of an extended version of the model developed by Carree et al. (2002). Specifically, our research aims to establish the two-way relationships between economic development and solo self-employment on the one hand and between economic development and employer entrepreneurship on the other, by analyzing a new dataset for 26 OECD countries over the period 1992–2008.

The value of the present paper is related to two observations. First, in recent years research into the economic meaning of entrepreneurship increasingly tends to distinguish between subcategories of the entrepreneurship phenomenon in terms of age of the business, firm size, innovativeness and growth aspirations (Lotti et al. 2003; Van Praag and Versloot 2008; Wennekers et al. 2010; Pellegrino et al. 2012; Haltiwanger et al. 2013). The present paper contributes to this new approach by explicitly distinguishing between solo self-employed and employer entrepreneurs. Secondly, in spite of the unmistakable revival of small-scale independent entrepreneurship (and particularly solo self-employment) in the last three decades, nevertheless recent research suggests that economies of scale and scope are still also relevant for macro-economic performance (Congregado et al. 2014; Van Praag and Van Stel 2013). The present paper also aims to contribute new insights in this area.

2 Literature review

In this short review of the literature, our point of departure is the two-way relationship between entrepreneurship and economic development, as highlighted in Sect. 1 of this paper. This means that we will distinguish between the determinants and the effects of entrepreneurship.

2.1 Determinants

2.1.1 Drivers of independent entrepreneurship in general

A quite general, multidisciplinary framework for explaining the rate of independent entrepreneurship (also known as business ownership or self-employment) at the country level is the so-called ‘eclectic theory of entrepreneurship’ developed by Verheul et al. (2002).Footnote 1 This framework combines various disciplines, including (neo-)classical economics, institutional economics, psychology, sociology and anthropology, and distinguishes between a supply and a demand side of entrepreneurship. From the demand side the framework focuses on factors influencing the industrial structure and the diversity of consumers’ tastes, such as technological development (Dosi and Nelson 2013), globalization, and changing standards of living. The supply side examines various structural characteristics of the population and how these affect the prevalence of individuals who opt for entrepreneurship. These include population growth, urbanization rates, participation of women in the labor market, income levels, and unemployment. In addition, institutions also play a crucial role in influencing an economy’s entrepreneurship rate. These include the fiscal environment for business, the generosity of social security arrangements, labor market regulations, intellectual property rights, bankruptcy law and the educational system. Finally, dominant cultural values influence the choice of individuals between becoming self-employed or working for others.

Against this background it is possible to study the historical decline in business ownership which has been manifest since at least the 19th century (Wennekers et al. 2010), and the revival of entrepreneurship in recent decades. The probably most influential underlying determinant is the process of economic development as measured by per capita income. The negative impact of income growth on the prevalence of independent entrepreneurship was clearly demonstrated in a seminal paper by Lucas (1978), which will be discussed in greater detail below. Apart from this negative influence of economic development on business ownership, secular developments in technology and in relevant institutions and cultural values act as drivers of more small business entrepreneurship (Congregado et al. 2014).

Carree et al. (2002, 2007) use the concept of a long-term ‘equilibrium rate’ or ‘natural rate’ of business ownership, which may be understood as the percentage in the labor force that the business ownership rates of individual countries tend to, given their stage of economic development. In a model consisting of three equations they study the interrelationship between business ownership and economic development (measured as per capita income), at the country level.Footnote 2 One equation describes the ‘equilibrium rate’ of business ownership as a function of the level of per capita income. A second equation explains changes in the rate of business ownership by an error-correction process towards this ‘equilibrium rate’, as well as by some other determinants. A third equation determines a possible negative influence on the growth rate of per capita income when the rate of business ownership is ‘out-of-equilibrium’. The full model will be discussed in the next section. This three-equation model was used, among other purposes, to investigate whether the assumed underlying ‘equilibrium rate’ of business ownership in OECD countries has shown a U-shaped or an L-shaped relationship with per capita GDP over the past 30 years. The empirical research so far was inconclusive. Carree et al. (2002) suggested a slightly better fit of the U-curve, while Carree et al. (2007), using more recent data, find the L-shape performing somewhat better. In both analyses the difference between the two curves is not statistically significant. Nonetheless, both curves imply a discontinuity in the historical linear decline of business ownership.

2.1.2 Drivers of solo self-employment

The determinants of solo self-employment can be found at both the demand and the supply side of the labor market (Wennekers et al. 2010). At the demand side there seem to be two main drivers. First, a higher level of economic development is usually accompanied by a higher presence of larger firms (Ghoshal et al. 1999), implying a larger supply of paid jobs and more stable wages (Lucas 1978; Parker 2009). Accordingly, economic development reduces the need to enter solo self-employment for lack of other options for work. This obviously is a negative influence. On the other hand, however, in many countries there also appears to be a growing trend for employer firms to subcontract to own account workers. This is often done to increase flexibility, to reduce minimum efficient scale (Burke 2011) and “to reduce wages and other financial obligations such as continued wage payment during slack, illness and maternity leave as well as employers’ contributions to social security” (Wennekers et al. 2010, p. 206). According to Beck (2000) the Western world now even faces a gradual disappearance of the ‘job for life’ and a ‘reversal to premodernity’ where many individuals are engaged in various labor market activities including part time jobs and self-employment.

At the supply side, economic development may influence the prevalence of solo self-employment through its effect on human motivations. While basic material and social needs are more prominent at low and medium levels of development, at a high level of prosperity a need for autonomy and self-realization comes to the fore (Maslow 1970). For some this need for autonomy will make solo self-employment an attractive option (Wennekers et al. 2010).

2.1.3 Drivers of employer entrepreneurship

As for the drivers of employer entrepreneurship, a major theoretical perspective is offered in the seminal article by Lucas (1978). According to this theory, economic development and the accompanying rise of real wages will enhance the opportunity costs of entrepreneurship, inducing the entrepreneurs of the least profitable (small) businesses to become managers (in paid jobs) in larger firms. This theory matches well with the observation by Ghoshal et al. (1999) with respect to a higher prevalence of larger firms at higher levels of economic development.

In a recent paper Congregado et al. (2014) follow Lucas (1978) by assuming that per capita income is a good proxy for per capita capital, as a consequence of which economic development would ceteris paribus imply increasing economies of scale, increasing average firm size and a declining (employer) self-employment ratio. In addition, other factors, largely unrelated to economic development and including the trends of globalization and the diffusion of ICT, may have a negative impact on average firm size. These trends may best be captured by a time trend. In a regression analysis for 23 OECD countries over the period 1972–2008, while allowing for ‘structural regime breaks’ for individual countries, Congregado et al. (2014) find significant support for continued increasing scale economies related to the process of economic development. At first sight a continuation of the underlying tendency towards increasing scale economies in modern economies presents a paradox in so far as the most highly developed economies also show relatively high start-up rates. However, a positive relationship between start-ups and per capita income at the higher end of economic development holds particularly for high-growth expectation early-stage entrepreneurship (Wennekers et al. 2010, pp. 216–218), while recent evidence shows it not to hold for solo and low-growth expectation early-stage entrepreneurial activity (Bosma et al. 2012, pp. 35–37). Accordingly, these relatively high start-up rates in the most highly developed economies could also imply a more competitive selection process, in which relatively large high-quality firms survive and prevail (Congregado et al. 2014).

2.2 Impact on economic growth

2.2.1 Drivers of economic growth

Entrepreneurship may influence economic growth via several intermediate linkages. A simple framework for disentangling the impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth in underlying intermediate linkages is provided in Thurik et al. (2002) which is based on Wennekers and Thurik (1999). Two major intermediate linkages in this framework are innovation and competition.

Innovation includes process and organizational innovations, as well as product and marketing innovations (Mohnen and Hall 2013, p. 48). The former two innovations often directly impact on productivity. The latter two are primarily directed at the penetration of existing markets or the development of new markets, and may indirectly influence productivity. There is also evidence for some degree of complementarity between the various types of innovation (Mohnen and Hall 2013, p. 60). Innovations can be introduced by new business start-ups and through corporate entrepreneurship in existing firms.

Competition is a complex phenomenon and includes various types such as competition on price, product quality or after sales service, and competition between products that are substitutes for each other. Competition activated by new start-ups, new products and new business ideas is particularly relevant for economic growth, triggering “… a restructuring of the economy through a wide array of reactions including … business exits, mergers, re-engineering (diffusion), and new innovations by incumbents” (Thurik et al. 2002, p. 164). Ultimately, selection of the most viable firms and the best ideas leads to a restructuring of the economy. At the aggregate level of industries, regions and national economies these processes may lead to higher productivity and to production growth.

In addition, other influences on economic growth include the catching up mechanism, the role of better human capital, scale economies and increased flexibility. In particular, scale economies may be a very important additional element. As was shown in the previous section, for many highly-developed economies there is in fact significant empirical support for continued increasing scale economies related to the process of economic development (Congregado et al. 2014). In addition, catching up may play a significant role as “countries which are lagging behind in economic development grow more easily … because they can profit from modern technologies developed in other countries” (Carree et al. 2002, p. 278).

2.2.2 Empirical evidence of the economic effects of entrepreneurship

Against this background we will now briefly survey a selection of some key results from the empirical macro-economic literature in this area.Footnote 3 In particular, whereas many studies link dynamic measures of entrepreneurship, reflecting newness, to macro-economic performance [e.g. start-up rates used by Audretsch and Keilbach (2004), or GEM’s total early-stage entrepreneurial activity rate used by Van Stel et al. (2005)], below we focus on studies linking a static measure of entrepreneurship, i.e. self-employment (also known as business ownership), to macro-economic performance. The latter type of studies is more closely related to the present study. Using static measures of entrepreneurship requires a different type of modelling as the link with economic performance is often found to be non-linear. In particular, when linking static measures of entrepreneurship to economic performance, the use of ‘equilibrium’ or ‘optimal’ rates of entrepreneurship is often appropriate.

An early study is by Carree et al. (2002), which was followed up by Carree et al. (2007). Their main hypothesis is that structural economic growth is influenced in a negative way by the deviation of the actual rate of self-employment from the ‘equilibrium rate’. In a regression analysis with data for 23 OECD countries in the period 1976–1996 they find empirical support for a symmetrical ‘growth penalty’, which means that “… economies can have both too few or too many business owners and both situations can lead to a growth penalty” (Carree et al. 2002, p. 285). Undershooting may imply a low level of competition and dynamism, while overshooting may cause the average scale of production to remain below optimum levels. In a follow-up study with data for the period 1980–2004, Carree et al. (2007, pp. 288–289) find support for a one-sided growth penalty in the sense that “particularly a business ownership rate below ‘equilibrium’ is harmful for economic growth”, while “… there may not be a growth penalty for the business ownership rate being in excess of the ‘equilibrium’ rate”. Carree et al. (2002, 2007) also find further support for the catching-up hypothesis.

Van Praag and Van Stel (2013) estimate extended versions of a macro-economic Cobb–Douglas production function, including capital, labor, R&D, enrolment in tertiary education and the business ownership rate as input factors, on a sample of 19 OECD countries for the period 1981–2006. They find significant results for both the business ownership rate and the squared business ownership rate, implying that there may be an optimal rate of entrepreneurship. They also find evidence that this optimal rate is negatively related to the enrolment in tertiary education, supporting the notion that “… business owners with higher levels of human capital run larger firms” (Van Praag and Van Stel 2013, p. 335). At an enrolment rate of 20 % the optimal entrepreneurship rate is around 14 % of the labor force, while the latter is around 12.5 % at an enrolment rate of 50 %. As the participation in tertiary education is positively related to the level of economic development, these results would imply a negative relationship between the optimal level of business ownership and GDP per capita.

The empirical investigations with respect to the contribution of entrepreneurship to productivity growth, as discussed in the review by Van Praag and Versloot (2008), differ in their definition of entrepreneurs and/or entrepreneurial firms versus their counterparts (including owner-managers versus employees, small versus large firms and young versus incumbent firms) and in the level of measurement (micro, meso and macro). Overall, the main conclusion of the review is that while entrepreneurs may lag behind in the level of productivity, the majority of studies “… show that entrepreneurs experienced higher growth in production value and labor productivity” (Van Praag and Versloot 2008, p. 120).

2.2.3 Economic effects of solo self-employment

There is very little empirical evidence on the economic contribution of the solo self-employed. A recent study in four sectors of industry in the Netherlands suggests that many solo self-employed are only somewhat more productive than employees (SEO 2010). However, they do provide higher flexibility to the firms that use their services and they share in the risks of overcapacity. In some sectors, such as the construction industry in particular, freelancers may be viewed as ‘the enablers of entrepreneurship’ for the firms hiring them “by enabling de-risking strategies, reducing financial constraints, increasing entrepreneurial strategic agility as well as facilitating market entry by start-ups” (Burke 2011, p. 25). On the other hand, the solo self-employed have themselves very limited possibilities to exploit scale economies. Finally, it is important to note that the solo self-employed are a heterogeneous category. They differ in motivation, in degree of autonomy and in ambition (Wennekers et al. 2010), as well as in their level of skills. ‘Marginal’ freelancers might be more productive as a regular employee while they may then receive continued education and training, and may develop more commitment to the business that employs them.

2.2.4 Economic effects of employer entrepreneurship

Employer entrepreneurs are owner-managers who employ personnel. While their enterprises differ in size, almost all of them operate in the SME-sector and on average they are relatively small. Their firms exclude the large corporations listed on the stock market as well as the many subsidiary firms owned by such corporations. Apart from differences in firm size, employer entrepreneurs are also a heterogeneous category in terms of the age of their enterprise, the sector of industry they operate in, their innovativeness and their ambitions for firm growth. Although many studies focus on the economic contribution of entrepreneurs running new or young firms versus older incumbent firms (e.g. Lotti et al. 2003; Haltiwanger et al. 2013), to our knowledge there are no empirical studies that specifically focus on employer entrepreneurs running smaller versus larger firms. In particular we do not know of studies measuring the economic contribution of independent employer entrepreneurs versus solo self-employed or versus large corporations and their subsidiary firms. However, studies focusing on the contribution of small firms come close. One such study, carried out for 17 European countries over the period 1990–1994, suggests that “… on average, a larger shift toward smallness is associated with a higher growth acceleration” (Audretsch et al. 2002, p. 93).

3 The model

In order to investigate the two-way relationships between economic development and solo self-employment on the one hand and between economic development and employer entrepreneurship on the other, we extend and refine the model by Carree et al. (2002). In particular, following Carree et al. (2002) we model the ‘natural’ or ‘equilibrium’ rate of solo self-employed (respectively employer entrepreneurs) in a country as a function of economic development. Next, we investigate whether deviations between the actual and ‘natural’ rates of solo self-employed (respectively employer entrepreneurs) at time t impact subsequent macro-economic growth.

The model reads as follows, where, in Eqs. (1) and (2), the following notation is used: \( \Delta_{4} X_{t} = X_{t} - X_{t - 4} \). Since we consider structural economic relationships, rather than cyclical ones, we include a lag of 4 years.

where

- E :

-

number of entrepreneurs per labor force,

- E* :

-

‘equilibrium’ number of entrepreneurs per labor force,

- \( U,\,\overline{U} \) :

-

unemployment rate and estimation sample average, respectively,

- \( LIQ,\overline{LIQ} \) :

-

labor income share and estimation sample average, respectively,

- D ITA :

-

dummy variable for Italy

- YCAP :

-

per capita GDP in thousands of purchasing power parities per US $ in 2000 prices,

- D OVER :

-

dummy variable with value 1 if E is higher than E*, and 0 otherwise,

- D EE :

-

dummy for East-European countries: Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland,

- \( \varepsilon_{1} ,\,\varepsilon_{2} \) :

-

uncorrelated disturbance terms of Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively,

- k :

-

indicator for type of entrepreneur: solo self-employed (solo) or employer entrepreneur (empl),

- i, t :

-

indices for country and year, respectively.

In the first equation the change over a period of 4 years in the (solo, respectively employer) entrepreneurship rate is explained by an error-correction term reflecting the gap between the equilibrium and the actual entrepreneurship rate at the beginning of the 4-year period, by the unemployment rate (a push-factor for entrepreneurship) and by the labor income share, a proxy for the earning differentials between expected profits of business owners and wage earnings (a pull-factor for entrepreneurship). We also include a dummy for Italy, as developments in Italian self-employment rates tend to be exceptional (Carree et al. 2002, 2007). Basically, Eq. (1) is estimated separately for solo self-employed and employer entrepreneurs.

In the second equation macro-economic growth rates are explained by (absolute) deviations between the equilibrium and actual entrepreneurship rates, distinguishing between type of entrepreneurship (solo self-employed versus employer entrepreneurs) and between the relative number of entrepreneurs shortfalling or exceeding the equilibrium rate (undershooting versus overshooting). In addition, a catching-up term is included allowing for higher growth rates of relatively lower developed countries benefiting from technologies developed in higher developed countries. Finally, a dummy for Eastern Europe is included as in the period shortly after the Fall of the Berlin Wall the determination of economic growth and the role of entrepreneurship therein have not been comparable to other (non-transition) OECD countries (Kornai 2006; Estrin and Mickiewicz 2011).

The third equation is a definition describing the shape of the relation between economic development (measured as per capita GDP) and the equilibrium number of entrepreneurs. In Eq. (3a) the equilibrium number of entrepreneurs is assumed to be a constant (hence, independent of economic development). In Eq. (3b), the ‘inverse’ relation, entrepreneurship gradually declines towards an asymptotic minimum value (of \( \alpha - \beta \)). In Eq. (3c) entrepreneurship is a linearly declining function of economic development. In Eq. (3d), finally, the ‘quadratic’ relation, entrepreneurship declines with per capita income up till a minimum (when \( YCAP_{it} \) equals \( - \beta /2\gamma \)) after which entrepreneurship increases with per capita income.Footnote 4

For a given type of entrepreneurship (solo self-employment or employer entrepreneurship)Footnote 5 the model is estimated by substituting the definition (3a), (3b), (3c) or (3d) into Eq. (1):

Having estimated (4a)–(4d), the parameter estimates of \( \alpha \), \( \beta \) and \( \gamma \) in (3a)–(3d) are calculated as reparametrizations of the estimated parameters in (4a)–(4d):

Using these parameter estimates, variable E* can be computed and incorporated in Eq. (2). In our empirical application we will insert all four different equilibrium specifications (3a)–(3d) into Eq. (1), and continue in Eq. (2) with the specification with the best statistical fit in Eqs. (4a)–(4d).

4 Data

4.1 Data sources

We use data for the 26 OECD countries listed in Table 1 (see Sect. 4.2), over the period 1992–2008. Our main variables of interest, the number of (non-agricultural) solo self-employed and the number of (non-agricultural) employer entrepreneurs, are computed by multiplying the total number of (non-agricultural) self-employed (business owners) according to Panteia/EIM’s COMPENDIA data base, by the share of solo self-employed (respectively the share of employer entrepreneurs) in the total (non-agricultural) number of independent entrepreneurs according to Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey.

Self-employed (business owners) in COMPENDIA are defined to include unincorporated and incorporated self-employed individuals but to exclude unpaid family workers.Footnote 6 In COMPENDIA numbers of self-employed reported in OECD Labour Force Statistics are harmonized across countries and over time.Footnote 7 For the model estimations in the present paper, version 2008.1 of the COMPENDIA data base is used.

In order to arrive at numbers of solo self-employed and employer entrepreneurs, the number of self-employed according to COMPENDIA is divided between these two types of entrepreneurs according to their relative shares in Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey.Footnote 8 In some cases we estimated missing data for these relative shares based on national sources and/or we corrected for trend breaks that occurred over time. We refer to Appendix 1 for a detailed account of these modifications to the Eurostat data.

In our empirical model the absolute number of entrepreneurs (for both types) is expressed as a share of the labor force. Data on the size of the labor force are taken from OECD Labour Force Statistics.

The data sources for the other variables used in our empirical model [see Eqs. (1)–(5d)] are as follows.

YCAP Gross domestic product per capita. The variables gross domestic product and total population are taken from OECD National Accounts and OECD Labour Force Statistics, respectively. GDP (in thousands of US $) is measured in constant prices. Furthermore, purchasing power parities of 2,000 are used to make the monetary units comparable between countries;

U Unemployment rate. It is measured as the number of unemployed as a fraction of the total labor force. The labor force consists of employees, self-employed persons, unpaid family workers, people employed by the armed forces and unemployed persons. The main data source for the unemployment rate is OECD Main Economic Indicators;

LIQ Labor income share. It is defined as the share of labor income (including the “calculated” compensation of the self-employed for their labor contribution) in the gross national income. Total compensation of employees is multiplied by (total employment/number of employees) to correct for the imputed wage income for the self-employed persons. Next, the number obtained is divided by total income (compensation of employees plus gross operating surplus and gross mixed income). The data of these variables are from OECD National Accounts.

4.2 Descriptive statistics

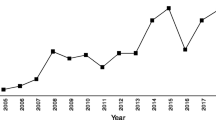

As mentioned earlier, the solo self-employment rate (employer entrepreneurship rate) is defined as the number of solo self-employed (employer entrepreneurs) as a fraction of the labor force. Descriptive statistics for the two components constituting these entrepreneurship rates (i.e. the total self-employment rate and the share of solo self-employed within total self-employment) are presented in Table 1. From the left-hand part of the table we see there is quite some variation in business ownership rates, both across countries (see also Fig. 1) and over time. This variation is well documented in the literature (see e.g. Wennekers et al. 2010).

Data patterns in the right-hand part of the table are less well-known. We see that for the listed countries in 2008, the share of solo self-employment in the total number of independent entrepreneurs ranges from 49.4 % in France to 78.4 % in the United Kingdom (see also Fig. 2 which uses the same ordering of countries as Fig. 1). Our data also show that there is quite some country variation in the development of solo self-employment over time. Over the period 1992–2008, the share of solo self-employed in total self-employment (i.e. vis à vis employer entrepreneurs) has increased in 15 out of 26 OECD countries in our data base, whereas it has decreased in 11 countries (see also Fig. 3).

5 Results of the regression analysis

5.1 The relation between economic development and entrepreneurship rates

We estimate Eqs. (4a)–(5d) using data for the 26 countries in Table 1 over the period 1992–2008. Since our model includes 4-year lags, and we want to avoid overlapping periods in our estimation sample, we use data with intervals of 4 years.Footnote 9 In particular we use data points for 1996, 2000, 2004 and 2008. This gives us a potential number of observations of 104 (26 countries times 4 periods). However, since the entrepreneurial sector in the former communist countries Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland had to be rebuilt almost completely after the collapse of communism (Johnson and Loveman 1995; Smallbone and Welter 2001), we remove the years 1996 and 2000 for these three countries, as the entrepreneurial process in these transition contexts is likely not well described by our model. Hence, we estimate the model using 98 observations. Following Carree et al. (2002, 2007) we estimate the model using weighted least squares (with population as the weight factor).

When incorporating the four different functional forms (3a)–(3d) into Eq. (1), and estimating the resulting Eqs. (4a)–(4d), we found that a constant [i.e. specification (3a)] best described the relation between economic development and the rate of solo self-employment, whereas a linearly declining function [i.e. specification (3c)] best described the relation between economic development and the rate of employer entrepreneurship. Table 2 presents estimation results for these statistically preferred specifications for the equilibrium rates of entrepreneurship.Footnote 10 We refer to Appendix 2 for full estimation details for all four possible equilibrium specifications.

Regarding the (constant) equilibrium rate of solo self-employment, we see from Table 2 that this rate is estimated at 7.1 % of the labor force. Regarding the declining equilibrium rate of employer entrepreneurship with economic development, on the domain of our estimation sample, the estimated equilibrium rate roughly varies between 1 and 6 % of the labor force.

For an interpretation of these findings we refer to Sect. 6.

5.2 The impact of entrepreneurship rates on economic growth

Using the preferred equilibrium specifications for both types of entrepreneurship (see Table 2), we estimate Eq. (2). Since the Japanese economic bubble burst in the early 1990s, Japan entered a long period of stagnation and economic disruption that persisted until 2003 (Hamada et al. 2011). Although each economy has its own specificities, we feel that, due to the severe consequences of Japan’s economic bubble burst, economic circumstances in Japan are too different in the estimation period under consideration to assume that economic growth rates can be explained in a similar way as growth rates in other OECD countries. We therefore include a dummy variable for Japan. Equation (2) is estimated with 98 observations.Footnote 11

Having established the equilibrium relations in Table 2, we observed that for employer entrepreneurship, the distribution of undershooting and overshooting observations (i.e. observations for which E < E* and E > E*, respectively) was quite uneven: 18 out of the 98 observations (i.e. only 18 %) were associated with undershooting (and, consequently, 82 % with overshooting). We judge this number of observations too low to make separate estimations for deviations in under and overshooting situations.Footnote 12 Therefore, for employer entrepreneurship, we just take the absolute deviation between E and E*, irrespective of under or overshooting.Footnote 13

Results are in Table 3. We see that for solo self-employment, there is a growth penalty both when the actual number of solo self-employed undershoots and overshoots the equilibrium number. For employer entrepreneurship we do not find a growth penalty.

Again, for an interpretation of these findings we refer to Sect. 6.

6 Discussion and conclusions

6.1 Major findings

For the natural rate of solo self-employment we find that a constant provides the best statistical fit, whereas the natural rate of employer entrepreneurship is best described by a linearly declining relationship with the level of economic development (measured as per capita income). The constant natural rate for solo self-employment may reflect the countervailing forces discussed before. On the one hand, as economies develop the number of people who choose for (solo) self-employment out of economic necessity usually decreases (Bosma et al. 2012, p. 25). On the other hand, in highly developed economies an increasing fraction of the labor force appears to prefer to work on their own account, independently of economic considerations, e.g. out of a desire for autonomy, and additionally there also appears to be trend for employer firms to subcontract to own account workers (Wennekers et al. 2010).

In addition, the declining relationship between the number of employer entrepreneurs and economic development may indicate that, while economies develop, higher numbers of ambitious, well-educated entrepreneurs emerge who run bigger firms. The number of relatively large SMEs then increases at the cost of an even bigger number of very small firms (see also Van Praag and Van Stel 2013). Since most of the employer self-employed own and run businesses with only a few employees, the number of employer self-employed decreases as a result of this shift to larger firms.

As regards the effect of deviations between the actual and natural rates of solo self-employed on economic growth, we find a growth penalty for both positive and negative deviations, indicating that economies can have too few but also too many solo self-employed. A lack of solo self-employed may indicate that the flexibility of these labor market participants, their contribution to reducing downtime risks and minimum efficient scale of the firms that hire them, and to enhancing the entrepreneurial agility of these firms (Burke 2011), are insufficiently utilized. A glut of solo self-employed may point at a lack of exploitation of scale economies, and at relatively low levels of productivity of ‘marginal’ solo self-employed compared with regular employees. Also, it may reveal the presence of substantial numbers of dependent self-employed (Roman et al. 2011). Finally, as regards the effect of deviations between the actual and natural rates of employer entrepreneurs, we do not find such a penalty, indicating that, even though the number of employers tends to decline with economic development, it is not necessarily harmful for countries to have a higher or lower number of such employers relative to the natural rate.

6.2 Implications

It is a well-known fact that the self-employed form a very heterogeneous group of labor market participants implying that it may be important to distinguish between different types of entrepreneurs. The present study shows that one relevant distinction is that between solo self-employed and employer entrepreneurs. We show, both theoretically and empirically, that the drivers and macro-economic impact of both types of entrepreneurs differ. As stated before we find that the natural or ‘equilibrium’ rate of solo self-employment seems to be independent of the level of economic development, whereas the natural rate of employer entrepreneurship is negatively related to the level of economic development. Possibly, in highly developed economies many solo self-employed are driven by non-economic motives (e.g. autonomy) whereas the firms subcontracting to these own account workers are driven by economic motives (e.g. flexibility and reducing financial obligations). At the same time employer entrepreneurs are also likely to be driven to a great extent by economic motives (including expansion and reaping of scale economies). This finding implies that, should governments be interested to influence the size of these respective groups of entrepreneurs, incentive structures must be different.

The question whether governments should indeed be interested to monitor these types of entrepreneurs is also related to our second set of empirical results, i.e. our finding that for solo self-employment deviations between the actual and ‘equilibrium’ rate are harmful for economic growth, whereas for employer entrepreneurs we do not find such a growth penalty. First, this implies that policy makers should particularly monitor the number of solo self-employed in their country, in order to maximize macro-economic growth. Apparently, a shortage of solo self-employed may hurt flexibility, competition and dynamism, while a glut of solo self-employed may be detrimental for macro-economic efficiency and for the exploitation of scale economies. In the latter case, two possible routes to decrease the number of solo self-employed might be to stimulate some (possibly higher quality) solo self-employed to become employer entrepreneurs and other (‘marginal’ and possibly lower quality) solo self-employed to become employees.

Secondly, as for the role of employer entrepreneurship, our results may imply that there are several paths (regimes) that lead to high macro-economic growth rates. Possibly a policy emphasis on (a relatively high number of) more slowly-growing and relatively small enterprises may be an equivalent alternative for the often advocated emphasis on (a relatively low number of) fast-growing and relatively large SMEs.

The insights which may be derived from the present paper can also be valuable for future research. For example, the results of the present paper suggest interesting new research opportunities in the area of the economic impact of the firm size distribution within the small business sector. In particular, future research might focus on the important questions how the optimal industry structure in terms of the share of the solo self-employed and of micro, small and medium-sized firms has developed in the past decades and how these developments may differ between sectors of industry. For an enhanced understanding of entrepreneurship dynamics it may also be of interest to investigate how the results are affected by the recent economic crisis. In addition, another interesting avenue of future research might be to distinguish between types of solo self-employed (ambitious versus dependent versus need for autonomy). Finally, the age of the businesses run by solo self-employed and employer entrepreneurs is also quite relevant. In particular, the important role of (ambitious, innovative) business start-ups and young, small firms (Lotti et al. 2003; Haltiwanger et al. 2013), and the constraints they may face (Schneider and Veugelers 2012), deserve further study in this respect. Future work in this area would also imply new data requirements.

Notes

This model will mutatis mutandis also be used in the empirical section of the present paper. For a mathematical treatment of the model see Sect. 3.

For a fuller review of the empirical literature on the economic benefits of entrepreneurship, including literature at the micro-level, the reader is referred to Van Praag and Versloot (2008).

Equations (3a)–(3d) do not include a country-specific constant, since that would imply that each country has its own unique equilibrium level of entrepreneurship (independent of per capita income). Although conceivable, this would rule out the possibility that a country has structurally more or fewer entrepreneurs (compared to other countries) than is optimal for economic growth. We want to allow for this possibility when testing Eq. (2). With country-specific equilibria in Eqs. (3a)–(3d), deviations from equilibrium would only relate to often relatively small movements around the country-equilibrium level. Hence, although it is certainly conceivable that different countries have different equilibrium rates of entrepreneurship (apart from differences resulting from different levels of economic development), e.g. due to different historic and cultural backgrounds, in this study we want to test whether structural deviations from a general natural entrepreneurship rate influence economic growth rates.

COMPENDIA is an acronym for COMParative ENtrepreneurship Data for International Analysis. See http://www.entrepreneurship-sme.eu for the data and Van Stel (2005) for a justification of the harmonization methods.

Data taken directly from the OECD Labour Force Statistics suffer from a lack of comparability across countries and over time. In particular, owner-managers of incorporated businesses are counted as self-employed in some countries, and as employees in other countries. Also, the raw OECD data suffer from many trend breaks relating to changes in self-employment definitions (Van Stel 2005).

In Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey, a division is made between “self-employed persons not employing any employees”, defined as persons who work in their own business, professional practice or farm for the purpose of earning a profit, and who employ no other persons, and “employers employing one or more employees”, defined as persons who work in their own business, professional practice or farm for the purpose of earning a profit, and who employ at least one other person. In this paper we label these groups as solo self-employed and employer entrepreneurs, respectively.

Inclusion of overlapping periods in the estimation sample may lead to a downward bias in the estimated standard errors of the coefficients (Carree et al. 2002).

The statistically preferred specifications are based on adjusted R2 values. For the solo self-employment Eqs. (4a)–(5d), a constant E* gave the best statistical fit but the differences in R2 are small, and in all specifications the value of E* is in the same order of magnitude (see Table 4 in Appendix 2). Moreover, for the constant E* [specification (3a)], the parameter estimate of α was highly significant, in contrast to (most) parameter estimates of α, β and γ for the other equilibrium specifications. For the employer entrepreneurship equation, we did not choose the quadratic specification as the parameter estimates for the linear and quadratic per capita GDP variables are clearly implausible, possibly due to multicollinearity. Moreover, as the turning point of the U-shaped relation lies outside the estimation domain, the estimated quadratic function is effectively monotonically decreasing, similar to the linear specification. Finally, for the employer entrepreneurship equation, the dummy for Italy proved to be non-significant (see Table 5 in Appendix 2). We therefore removed the dummy from the re-estimation presented in Table 2.

For our sample of 98 observations, the weighted correlation between the two absolute deviation variables in Eq. (2) is 0.4, while the unweighted correlation is 0.2. We therefore conclude that our estimations do not suffer from multicollinearity.

For solo self-employment this distribution is much more even: 60 % undershooting (59 observations) and 40 % overshooting (39 observations).

We are thus not able to establish separate effects of deviating from equilibrium for under and overshooting situations.

In Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey, a division is made between “self-employed persons not employing any employees”, defined as persons who work in their own business, professional practice or farm for the purpose of earning a profit, and who employ no other persons, and “employers employing one or more employees”, defined as persons who work in their own business, professional practice or farm for the purpose of earning a profit, and who employ at least one other person. In this paper we label these groups as solo self-employed and employer entrepreneurs, respectively.

Please note that, although the quadratic specification has a similar adjusted R2 value as the linear specification, coefficients for both per capita income terms are not significant. Moreover, both variables have an unexpected sign.

References

Audretsch, D. B., Carree, M. A., Van Stel, A. J., & Thurik, A. R. (2002). Impeded industrial restructuring: the growth penalty. Kyklos, 55(1), 81–98.

Audretsch, D. B., Grilo, I., & Thurik, A. R. (2007). Explaining entrepreneurship and the role of policy: a framework. In D. B. Audretsch, I. Grilo, & A. R. Thurik (Eds.), Handbook of research on entrepreneurship policy (pp. 1–17). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Audretsch, D. B., & Keilbach, M. (2004). Entrepreneurship capital and economic performance. Regional Studies, 38(8), 949–959.

Beck, U. (2000). The brave new world of work. Cambridge: Polity.

Bosma, N. S., Wennekers, S., & Amoros, J. E. (2012). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2011 extended global report: Entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial employees across the globe. Babson Park: Babson College, Santiago: Universidad del Desarollo, Kuala Lumpur: Universiti Tun Abdul Razak and London: Global Entrepreneurship Research Association.

Burke, A. (2011). The entrepreneurship enabling role of freelancers: theory with evidence from the construction industry. International Review of Entrepreneurship, 9(3), 1–28.

Carree, M. A., & Thurik, A. R. (2010). The impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth. In D. B. Audretsch & Z. J. Acs (Eds.), Handbook of entrepreneurship research (pp. 557–594). Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer.

Carree, M., Van Stel, A., Thurik, A. R., & Wennekers, S. (2002). Economic development and business ownership: an analysis using data of 23 OECD countries in the period 1976–1996. Small Business Economics, 19(3), 271–290.

Carree, M., Van Stel, A., Thurik, A. R., & Wennekers, S. (2007). The relationship between economic development and business ownership revisited. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 19(3), 281–291.

Congregado, E., Golpe, A., & Van Stel, A. (2014). The role of scale economies in determining firm size in modern economies. The Annals of Regional Science, 52(2), 431–455.

Dosi, G., & Nelson, R. R. (2013). The evolution of technologies: an assessment of the state-of-the-art. Eurasian Business Review, 3(1), 3–46.

Estrin, S., & Mickiewicz, T. (2011). Entrepreneurship in transition economies: the role of institutions and generational change. In M. Minniti (Ed.), The dynamics of entrepreneurship: evidence from the global entrepreneurship monitor data (pp. 181–208). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gartner, W. B. (1985). A conceptual framework for describing the phenomenon of new venture creation. Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 696–706.

Ghoshal, S., Hahn, M., & Moran, P. (1999). Management competence, firm growth and economic progress. Contributions to Political Economy, 18(1), 121–150.

Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R. S., & Miranda, J. (2013). Who creates jobs? Small versus large versus young. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2), 347–361.

Hamada, K., Kashyap, A. K., & Weinstein, D. E. (Eds.). (2011). Japan’s bubble, deflation, and long-term stagnation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hartog, C., Parker, S. C., Van Stel, A., & Thurik, A. R. (2010). The two-way relationship between entrepreneurship and economic performance. EIM Research Report, H200822. Zoetermeer: EIM.

Hipple, S. (2004). Self-employment in the United States: an update. Monthly Labor Review, July, 13–23.

Johnson, S., & Loveman, G. (1995). Starting over in Eastern Europe: entrepreneurship and economic renewal. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Kornai, J. (2006). The great transformation of Central Eastern Europe: success and disappointment. Economics of Transition, 14(2), 207–244.

Lotti, F., Santarelli, E., & Vivarelli, M. (2003). Does Gibrat’s law hold among young, small firms? Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 13(3), 213–235.

Lucas, R. E, Jr. (1978). On the size distribution of business firms. Bell Journal of Economics, 9(2), 508–523.

Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper and Row.

Mohnen, P., & Hall, B. H. (2013). Innovation and productivity: an update. Eurasian Business Review, 3(1), 47–65.

Parker, S. C. (2009). Why do small firms produce the entrepreneurs? Journal of Socio-Economics, 38(3), 484–494.

Pellegrino, G., Piva, M., & Vivarelli, M. (2012). Young firms and Innovation: a microeconometric analysis. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 23(4), 329–340.

Roman, C., Congregado, E., & Millan, J. (2011). Dependent self-employment as a way to evade employment protection legislation. Small Business Economics, 37(3), 363–392.

Schneider, C., & Veugelers, R. (2012). On young highly innovative companies: why they matter and how (not) to policy support them. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(4), 969–1007.

SEO (2010). Markt èn hiërarchie; kosten en baten van het zzp-schap [Market and hierarchy; costs and benefits of solo self-employment]. Amsterdam: SEO.

Smallbone, D., & Welter, F. (2001). The distinctiveness of entrepreneurship in transition economies. Small Business Economics, 16(4), 249–262.

Thurik, A. R., Wennekers, S., & Uhlaner, L. M. (2002). Entrepreneurship and economic performance: a macro perspective. International Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 1(2), 157–179.

Van Praag, C. M., & Van Stel, A. (2013). The more business owners, the merrier? The role of tertiary education. Small Business Economics, 41(2), 335–357.

Van Praag, C. M., & Versloot, P. H. (2008). The economic benefits and costs of entrepreneurship: a review of the research. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 4(2), 65–154.

Van Stel, A. (2005). COMPENDIA: harmonizing business ownership data across countries and over time. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1(1), 105–123.

Van Stel, A., Carree, M., & Thurik, A. R. (2005). The effect of entrepreneurial activity on national economic growth. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 311–321.

Van Stel, A., Cieslik, J., & Hartog, C. (2010). Measuring business ownership across countries and over time: extending the COMPENDIA data base. EIM Research Report, H201019. Zoetermeer: Panteia/EIM.

Verheul, I., Wennekers, S., Audretsch, D. B., & Thurik, A. R. (2002). An eclectic theory of entrepreneurship. In D. B. Audretsch, A. R. Thurik, I. Verheul, & S. Wennekers (Eds.), Entrepreneurship: determinants and policy in a European–US comparison (pp. 11–81). Boston/Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Wennekers, S. (2006). Entrepreneurship at country level; economic and non-economic determinants. ERIM Ph.D. Series Research in Management, vol. 81. Rotterdam: Erasmus Research Institute of Management (ERIM).

Wennekers, S., & Thurik, A. R. (1999). Linking entrepreneurship and economic growth. Small Business Economics, 13(1), 27–55.

Wennekers, S., Van Stel, A., Carree, M., & Thurik, A. R. (2010). The relationship between entrepreneurship and economic development: is it U-shaped? Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 6(3), 167–237.

Wennekers, S., Van Stel, A., Thurik, A. R., & Reynolds, P. D. (2005). Nascent entrepreneurship and the level of economic development. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 293–309.

Acknowledgments

The paper has been written in the framework of the research program SCALES, carried out by Panteia/EIM and financed by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: construction of data for solo self-employment and employer entrepreneurship

As mentioned in Sect. 4.1, in this paper we use data for 26 OECD countries over the period 1992–2008. Our main variables of interest, the number of (non-agricultural) solo self-employed and the number of (non-agricultural) employer entrepreneurs, are computed by multiplying the total number of (non-agricultural) self-employed (business owners) according to Panteia/EIM’s COMPENDIA data base, by the share of solo self-employed (respectively the share of employer entrepreneurs) in the total (non-agricultural) number of independent entrepreneurs according to Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey, or, for non-European countries, according to national sources.

For documentation of the methodology used in COMPENDIA to measure the total number of self-employed, we refer to Van Stel (2005) and Van Stel et al. (2010). In the present appendix we will provide details as to how the time series for the share of solo self-employed (respectively the share of employer entrepreneurs) in the total (non-agricultural) number of independent entrepreneurs, as used in this paper (see the right panel of Table 1), have been constructed.

In principle, we use the relative shares of solo self-employed and employer entrepreneurs in total self-employment according to Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey.Footnote 14 However, in some cases we needed to correct for trend breaks over time or estimate missing data in order to arrive at an annual time series 1992–2008 which, for each of the 26 countries used in this study, is complete and consistent over time. When we correct for trend breaks in the time series for the share of solo self-employed, we always take the level for the most recent year as the point of departure, and adjust the data for earlier years, instead of the other way around.

We will now provide details of the annual time series 1992–2008 for the share of (non-agricultural) solo self-employed in total (non-agricultural) self-employment for each of the 26 countries.

1.1 Austria

Data for the years 2004–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. Between 2003 and 2004 a trend break occurs in the Eurostat data. We remove the trend break by using the average of relative changes 2002–2003 and 2004–2005 to estimate relative change 2003–2004 (we thus interpolate the growth rate of the solo self-employment share). This growth rate is then applied (backwards) to the share of solo self-employed in 2004 to arrive at a share in 2003 which is consistent with the level in 2004. For the years 1995–2003 we again use relative annual changes in the share of solo self-employed according to Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. For the years 1992–1994 data are missing and, although admittedly a rough proxy, we set the share of solo self-employed in these years equal to the share in 1995 as derived above.

1.2 Belgium

Data for the years 1999–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. A trend break in the Eurostat data between 1998 and 1999 has been removed in a similar fashion as described above for Austria.

1.3 Denmark

Data for the years 1992–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey.

1.4 Finland

Data for the years 1995–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. For the years 1992–1994 data are missing and, although admittedly a rough proxy, we set the share of solo self-employed in these years equal to the share in 1995.

1.5 France

Data for the years 1992–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey.

1.6 Germany

Data for the years 1992–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey.

1.7 Greece

Data for the years 1992–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey.

1.8 Ireland

Data for the years 1992–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey.

1.9 Italy

Data for the years 2004–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. A trend break in the Eurostat data between 2003 and 2004 has been removed in a similar fashion as described above for Austria.

1.10 Luxembourg

Data for the years 2004–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. Between 2002 and 2004, two consecutive trend breaks seem to occur in the Eurostat data. As a rough proxy we set the share of solo self-employed in 2003 equal to that in 2004. Next, we use the average of relative changes 2001–2002 and 2004–2005 to estimate relative change 2002–2003. This growth rate is then applied (backwards) to the share of solo self-employed in 2003 to arrive at a share in 2002 which is consistent with the level in 2003 and later. For the years 1995–2002 we again use relative annual changes in the share of solo self-employed according to Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. Finally, a trend break in the Eurostat data between 1994 and 1995 has been removed in a similar fashion as described above for Austria.

1.11 The Netherlands

Data for the years 1992–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey.

1.12 Portugal

Data for the years 1992–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey.

1.13 Spain

Data for the years 1992–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey.

1.14 Sweden

Data for the years 1995–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. For the years 1992–1994 data are missing and, although admittedly a rough proxy, we set the share of solo self-employed in these years equal to the share in 1995.

1.15 United Kingdom

Data for the years 1992–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey.

1.16 Iceland

Data for the years 1995–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. For the years 1992–1994 data are missing and, although admittedly a rough proxy, we set the share of solo self-employed in these years equal to the share in 1995.

1.17 Norway

Data for the years 1995–2008 are provided by Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. However, by comparing these data with self-employment data from OECD Labour Force Statistics, we know that these data primarily relate to the unincorporated self-employed, and that the incorporated self-employed are mostly excluded (see Van Stel 2005). Since we know from other countries that the solo self-employment shares are quite different for unincorporated and incorporated self-employed, we make a correction. We will use a weighted average of the solo self-employment shares for the unincorporated and incorporated self-employed, where we use the shares of unincorporated and incorporated self-employed in total self-employment as weights. These weights are derived from Panteia/EIM’s COMPENDIA data base, see Van Stel (2005). For the unincorporated self-employed we use the solo self-employment share according to Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. Based on information from other countries, we set the solo self-employment share for the incorporated self-employed equal to 40 %. Although admittedly a very rough proxy, we feel that it is still better than making no correction at all (as it is then implicitly assumed that the shares of solo self-employed are equal for unincorporated and incorporated self-employed, which is known to be unrealistic). For the years 1992–1994 data in Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey are missing and, although admittedly a rough proxy, we set the share of solo self-employed in these years equal to the share in 1995 as derived above.

1.18 Switzerland

Data for the years 1996–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. For the years 1992–1995 data are missing and, although admittedly a rough proxy, we set the share of solo self-employed in these years equal to the share in 1995.

1.19 United States

For the United States, to our knowledge, no information is available concerning the share of solo self-employed versus employers which relates to the sum of unincorporated and incorporated self-employed together, which is the self-employment definition used in Panteia/EIM’s COMPENDIA data base, and also the definition used in the present study. From countries reporting the solo self-employment share separately for unincorporated and incorporated self-employed, such as Canada and Australia, we know however that the share of solo self-employed is much higher for the unincorporated self-employed than for the incorporated self-employed. Hence, if no data on the aggregate solo self-employment share (at the level of the sum of unincorporated and incorporated self-employed together) is available, it is important to account for the different solo self-employment shares between the unincorporated and incorporated self-employed.

Basically, for the United States we will use a weighted average of the solo self-employment shares for the unincorporated and incorporated self-employed, where we use the shares of unincorporated and incorporated self-employed in total self-employment as weights. These weights are derived from Panteia/EIM’s COMPENDIA data base, see Van Stel (2005) and Van Stel et al. (2010; their Table 6).

Next, for the unincorporated self-employed we use data on the solo self-employment share from Hipple (2004), his Table 9. This table provides data for the period 1995–2003. As both the level and development of the solo self-employment share for the unincorporated self-employed in the US over this period is quite similar to Canada, we add data for the years 1992–1994 and 2004–2008 based on the relative annual changes in the share of solo self-employed for the unincorporated self-employed in Canada (see description below).

For the incorporated self-employed we do not have information on the share of solo self-employed. Therefore, we assume that the solo self-employment share for the incorporated self-employed in the US equals that of Canada. Even though this assumption may not be unreasonable, given that we know that the solo self-employment share for the unincorporated self-employed in the US is also similar to Canada, we still realize this is quite a rough approximation. The impact of this inexactness on the aggregate solo self-employment share may not be too big though, given that the incorporated self-employed form the minority of self-employed (i.e. their weight is lower than that of the unincorporated self-employed).

1.20 Japan

The Statistics Bureau of Japan publishes data on the number of self-employed with and without employees. Data are available for the whole period 1992–2008.

1.21 Canada

Based on their national labour force survey, Statistics Canada publishes the number of self-employed in the Canadian economy in four categories, along the dimensions self-employed in an unincorporated or incorporated enterprise, and self-employed with or without paid help. We use the percentage “without paid help” for the sum of unincorporated and incorporated self-employed (consistent with the definition in COMPENDIA). Data are available for the whole period 1992–2008.

1.22 Australia

Similar to Canada, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) publishes the number of self-employed in the Australian economy in four categories, along the dimensions self-employed in an unincorporated or incorporated enterprise, and self-employed with or without employees. The information is published by ABS in the so-called ‘6359.0 Forms of Employment’ publications, resulting from the Forms of Employment Survey, a supplement to the Labour Force Survey. The information on the different categories of self-employed is available for the years 1998, 2001, 2004, 2006 and 2007. Data for the other years are missing. For the missing years between 1998 and 2007 we use linear interpolation of the solo self-employment share. We set the share in 2008 equal to that in 2007. Finally, although admittedly a rough proxy, we set the share of solo self-employed in the years 1992–1997 equal to the share in 1998.

1.23 New Zealand

Statistics New Zealand publishes data on the number of ‘employers’ and ‘self-employed’ (basically entrepreneurs with and without employees) in their ‘status in employment’ topic. Data are available for the years 1991, 1993, 1996, 1998, 2001 and 2006. Data for the other years are missing. For the missing years between 1991 and 2006 we use linear interpolation of the solo self-employment share. Although admittedly a rough proxy, we set the share in 2007 and 2008 equal to that in 2006.

1.24 Czech Republic

Data for the years 1997–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. For the years 1992–1996 data are missing and, although admittedly a rough proxy, we set the share of solo self-employed in these years equal to the share in 1997. Note that in the regression analysis we only use data for Czech Republic from 2000 onwards.

1.25 Hungary

Data for the years 2000–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. A trend break in the Eurostat data between 1999 and 2000 has been removed in a similar fashion as described above for Austria. For the years 1996–1999 we again use relative annual changes in the share of solo self-employed according to Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. For the years 1992–1995 data are missing and, although admittedly a rough proxy, we set the share of solo self-employed in these years equal to the share in 1996 as derived above. Note that in the regression analysis we only use data for Hungary from 2000 onwards.

1.26 Poland

Data for the years 2000–2008 are taken directly from Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey. For the years 1992–1999 data are missing and, although admittedly a rough proxy, we set the share of solo self-employed in these years equal to the share in 2000. Note that in the regression analysis we only use data for Poland from 2000 onwards.

Appendix 2: determining the shape of relation with economic development

In Tables 4 and 5 we show the estimation results of Eqs. (4a)–(4d) and (5a)–(5d) for all four equilibrium specifications (3a)–(3d). We see that for solo self-employment, a constant provides the best statistical fit, whereas for employer entrepreneurship a linearly declining relation with per capita income provides the best fit.Footnote 15

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Stel, A., Wennekers, S. & Scholman, G. Solo self-employed versus employer entrepreneurs: determinants and macro-economic effects in OECD countries. Eurasian Bus Rev 4, 107–136 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-014-0003-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-014-0003-z