Abstract

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) includes varied medical and healthcare systems, healing practices, and products that are outside of allopathy/biomedicine. The aim of this study was to examine US South Asian youths’ beliefs, practices, decision-making, and experiences of using CAM. Ten focus group discussions with 36 participants were conducted. Data were coded deductively and inductively by four coders, working in pairs. Thematic analysis was performed. Disagreements were resolved through consensus. The results showed that CAM was appealing because of its often low cost, ease of access, family traditions to use CAM, and the perception that it was safe to use. Participants exercised pluralistic health choices. Some responses suggested a hierarchy wherein allopathy was used for serious, acute issues, and CAM for much of the remaining issues. The high use of and trust in CAM among young US South Asians raises important issues (e.g., provider support and integration to prevent potential interactions and avoid delaying allopathic treatment). More exploration is needed about the decision-making processes of US South Asian youth, including the perceived benefits/limitations of allopathy and CAM. US healthcare practitioners should familiarize themselves with South Asian social and cultural beliefs about healing to provide culturally-appropriate services and enhance patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The term complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is used to refer to a wide range of healthcare practices that are outside the conventional Western biomedical model of medicine [1]. These mostly have roots in what are referred to as developing countries [2]. Depending on the culture and region, these practices may include the use of herbs and different foods believed to have inherent medicinal qualities (e.g., warming versus cooling foods), traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurveda, Unani medicine, and Homeopathy, among other modalities and therapies.

There is no consensus in the literature about terminology or definitions for non-Western medicine given the plethora of therapies, historical and geopolitical evolution of their adoption, and differences in academic disciplines. For example, related terms in the literature include integrative, complementary and traditional health practices (ICTHP), and traditional and complementary medicine (T&CM) [3]. Furthermore, some literature differentiates between traditional medicine on one hand and complementary and alternative medicine on the other [4]. The NIH proposed a five-category approach to describe CAM: (a) biologically based practices (vitamins and mineral supplements, herbals, and unconventional diets); (b) manipulative and body-based approaches (e.g., massage and chiropractic care); (c) mind–body medicine (spiritual, meditative, and relaxation techniques); (d) alternative medical systems (e.g., acupuncture); and (e) energy medicine (e.g., Reiki) [5].

Modern Western medicine (biomedicine or allopathy) is based on scientific advances that began around 1850. It incorporated new discoveries (e.g., the germ theory, use of penicillin, and X-ray technology) to treat patients and improve health [2]. The public health advances and growth in science and technology along with the process of colonialism led to the spread of Western medicine to other countries [2]. Presently, Western medicine is frequently privileged over traditional forms of medicine. The latter may lack adequate infrastructure, personnel, and funding despite official policies to promote traditional medicine [6].

The use of CAM may be of special interest among immigrant populations in Western countries, as they may rely on them due to familiarity, traditional beliefs, and lack of health insurance needed to access Western medicine in some countries. Especially among South Asians, medical pluralism such as the simultaneous use of Western medicine and CAM may be especially prevalent [7]. However, Western medical and nursing professionals may have low familiarity with CAM. The reasons for Western mainstream medicine and providers being unaware of and/or reluctant to learn about CAM, include profit motive in pharmaceuticals, beliefs that some or all CAM remedies are dangerous or unscientific and differences in health paradigms including rejection of non-Western models of care [2].

Immigrant youth may help bridge cultures of their communities and the larger society. This paper explores the views of youth of South Asian origin living in the US, about the use of CAM. South Asia comprises India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, and the Maldives. The US South Asian population is important to study because it is one of the most rapidly growing immigrant groups in the USA [8]. Indian Americans comprise the second largest Asian sub group (21%) of the US Asian population, after Chinese Americans (24%) [9]. There are both differences and similarities within South Asians. They are studied together as a group because of the cultural similarities and historical linkages in the region that in turn lead to similar world views and health behaviors [7, 10]. The three most populous South Asian countries, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, were actually one country until 1947, when India was partitioned into Pakistan (including East Pakistan which is now Bangladesh) and India [10]. Subsequently, Bangladesh gained independence from Pakistan in 1971.

Within the diaspora, identification with the term “South Asian” is increasing, as immigrants from these countries identify affinities with each other and their similar cultural practices in the context of their host countries. Some South Asian languages are spoken across multiple countries in the region (e.g., Urdu, Bengali, Tamil, and Punjabi). Religions that originated in South Asia such as Hinduism, Sikhism, Buddhism, and Jainism are practiced by a large majority of South Asians. Other major religions practiced in the region include Islam and Christianity. In some instances, families may be split across South Asian countries for reasons such as only a part of the family being able to migrate upon partition of the country. Family-based decision-making, collectivism, and the role of adult children in making healthcare decisions for parents and older relatives are some aspects of healthcare decision-making among this population [11]. However, research on CAM use among US South Asians is limited. This paper seeks to contribute to reducing this gap in knowledge. The research question for this qualitative inquiry was, “What are the beliefs, practices, motivators and experiences of using CAM among South Asian youth living in the US?”.

Literature Review

Limited information about CAM use among US South Asians is available [12,13,14]. Most US South Asians were born outside the USA, and their health behaviors are influenced by practices in their countries of origin [8], including CAM use. Youths in particular have to navigate the bicultural practices of both their countries of origin and the USA. Therefore, literature from South Asian countries as well as other countries about the South Asian diaspora (e.g., Australia and Canada) can help us in contextualizing, understanding, and supplementing the findings about CAM use from US South Asians.

CAM Use in South Asia

This section provides an overview of the CAM modalities, context, and factors associated with CAM use in South Asia. The history of CAM use in South Asia itself actually dates back to the beginning of the Indus valley civilization and writing of the sacred texts of the four Vedas. Ayurveda which literally translates as “the science of life” is considered to be reflected in Rigveda or Atharvaveda, followed by subsequent treatises [15]. Over the centuries, additional therapies have been adopted leading to a vibrant medical pluralism. India, the most populous South Asian country, recognizes the following traditional systems of medicine: Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani Medicine, Siddha, Sowa Rigpa, and Homeopathy, together known by the acronym (AYUSH). These systems are presently taught in specialized colleges [3]. Over time, for-profit companies have started selling AYUSH products over the counter and marketing those using commercial techniques to appeal to modern consumers, thus removing the need to consult a practitioner in some cases [16]. CAM practitioners may actually combine different therapies in which they may not have been formally trained [17]. An informal ranking of medical systems in India has emerged, with allopathy at the top, some AYUSH systems next, followed by local healing traditions [6].

Findings about CAM use in South Asia are derived from studies with frequently small sample sizes that seek to investigate health-seeking behavior. The results suggest that among some patients, CAM may be used only for specific illnesses or conditions (e.g., constipation), while among other patients one may encounter a multi-therapy approach (medical pluralism) that includes CAM and other therapies [18]. It is estimated that more than half of the population in India already opts for pluralistic healthcare choices [19]. It is commonly found that CAM is used more for chronic conditions, as compared to acute conditions, for symptom management, improving immunity, increasing quality of life, and coping with side effects from allopathic medicine [20]. Additionally, home remedies are likely to be preferred for common diseases (e.g., cold, vomiting, fever, general aches, headache, and asthma) and conditions such as pregnancy [20,21,22]. Commonly used herbs, spices, and other botanicals including turmeric, neem, honey, vetiver, black nightshade, vinca, plantain stem, holy basil, fenugreek, yogurt, banana, cardamom, rice, salt-sugar water, herbal tea (e.g., joshanda and kahwa), oregano, garlic, onion, and fuller’s earth, among others [21,22,23].

In South Asia, both wealthy and poor patients may use CAM for several reasons. Poorer patients may be forced to consult unqualified allopathic practitioners and/or CAM practitioners due to a lack of other options [24]. Additionally, though cost-associated barriers are seen in the long-term usage of CAM for certain conditions or diseases (e.g., diabetes), the low cost and high accessibility of other Ayurvedic treatments (e.g., choornam/medicinal powder consumed orally) are quite reasonable, aiding in their consistent usage [25]. Elevation of CAM usage among poorer households can also partly be explained by the increased susceptibility to diseases encountered by this group [26]. Large population studies also underscore the impact that the absence of health insurance coverage has on indigent individuals’ treatment choices [27]. Furthermore, some data demonstrate that those in higher socioeconomic classes self-medicate (with both CAM and modern medicines) at higher rates, compared to those in lower socioeconomic groups. [28]. Treatment preference, therefore, is influenced by both availability and cost [29]. Ultimately, the pattern that has evolved in terms of the association between CAM use and cost is one, where utilization (as mentioned above) is the highest among both the richest (who may self-medicate at high rates) [28] and poorest communities in South Asia [30].

It is important to investigate if younger populations are using CAM for the same reasons as older populations. Some evidence suggests that younger individuals in India demonstrate elevated inclinations towards CAM, compared to older individuals, who may be unwilling to wait for symptom resolution [31]. However, older individuals with chronic conditions tend to favor CAM [32]. A common finding is that patients of all ages often prefer CAM for treating many ailments due to concerns surrounding dependency and the perceived side effects associated with allopathic treatments [25]. There is inconsistency in study findings about whether these concerns delay individuals’ pursuit of allopathic options for serious diseases like cancer [29], or if they compel individuals to increase and broaden their utilization of all the health care services that they have access to [32].

Religious beliefs, faith, traditions, and superstitions have also all been linked to CAM usage, but the presence of other factors (e.g., economic status, gender, education level, age, and living conditions) affects the specific way that utilization occurs [26]. Cultural traditions also play an important role in CAM use in South Asia. For example, Sowa rigpa is a popular treatment in Bhutan for diseases such as arthritis, rheumatism, ulcers, stomach disorders, headaches, and skin diseases [33]. However, measuring the impact of cultural influences on CAM usage is challenging. South Asia is not a monolith in terms of heritage, traditions, and beliefs. Neither those varying customs are static [34]. Culture is, therefore, a nuanced force that interacts with different socioeconomic factors and demographic elements in interesting ways. Overall, the current cultural trend reflects a desire to deepen investment in CAM use in conjunction with allopathic treatments in order to satisfy the unmet needs that may arise from using either in isolation [32].

CAM Use Among the South Asian Diaspora

CAM use among the South Asian diaspora may be affected by reasons such as perceived discrimination in healthcare settings, in addition to factors that are reported in studies in South Asia such as belief in efficacy, lower side effects, and tradition. The literature about CAM use among ethnic minorities, as a whole, provides some context about use among US South Asians. A systematic review of CAM use among ethnic minorities in several countries including the USA has indicated that the association between CAM use and being an ethnic minority is not consistent, with some studies actually showing higher use among White populations [35]. The reasons for preferring CAM were multifarious, with many reporting that it was perceived to be safer, natural, and more effective than biomedicine [35]. Many studies also reported that dissatisfaction with the patient-provider interaction in Western countries (e.g., discrimination on account of accent or cultural background, feeling rushed, and feeling provider was uninterested inpatient care) lead many immigrants to prefer CAM instead [35].

The literature about medical pluralism among South Asian diaspora in the USA, UK, Canada, and Ireland shows that healthcare practices reflect a complex interaction of beliefs, traditions, and influences from family and one’s peers [7]. In addition to traditional systems of medicine (e.g., Ayurveda), other CAM strategies adopted by South Asian immigrants included offering prayers, going to holy places, checking horoscopes, wearing gemstones and blessed amulets, fasting, and taking advice from spiritual healers [7]. CAM use is influenced by perceptions about severity of illness [36], time taken to cure illness, beliefs about efficacy of treatments [36, 37], beliefs about side effects of different treatments [7;37–38], empathy, availability of other options, family influence [23, 37,38,39], desperation for a cure or symptomatic relief [36, 38], and acculturation [36, 38].

Findings about CAM use among US South Asians are derived mostly from studies that focused exclusively on Asian Indians (the largest subgroup among South Asian immigrants) as well as studies that include several Asian subgroups. Studies have shown widespread use of traditional therapies in general [39], but some studies show lower than expected CAM use for treating health conditions (e.g., 9% among Asian Americans), raising questions of underreporting and lack of representative data [40]. Some data suggest that elderly Asian Indians were more likely to use CAM for treatment than some other Asian groups [40]. A 2006 study of Asian Indians in the USA suggested that respondents with greater length of residence in the USA were more likely to use allopathic medicines than recent immigrants [36]. A 2009 study of Asian Indians (N = 64) found high awareness of Ayurveda (95%) [13]. About 78% had knowledge of Ayurvedic products or treatments, and more than half (59%) had ever used or were presently using Ayurveda. A cross sectional study from 2010 of Asian Indians from 7 US cities (N = 1824) found that the majority of the respondents were using at least one type of CAM. CAM use was positively associated with older age, female gender, barriers to access to care, and spirituality [14].

There is absence of consistency in findings about whether use of CAM is mostly a second-line treatment or an alternative to allopathic medicine. At least one study found that Asian Indians categorized illnesses into major and minor depending on their symptoms [36]. For severe illness, allopathic treatment was generally favored. Self-treatment through CAM as an alternative or second-line treatment seemed to be based on Ayurvedic principles, though people did not formally know these principles [36].

A concerning finding is that CAM use is frequently not disclosed to providers [7] due to lack of confidence in the health-care system and fear of being blamed, labeled as backward, and fear of discrimination [7, 23, 38, 41]. One study among US Asian Indians reported that only 18% informed Western medical doctors about Ayurveda use [13]. Furthermore, among some users, CAM use may be driven by family pressure instead of the user’s belief in its efficacy. A study among South Asian epilepsy patients in the UK found patients used CAM even if they did not believe it to be efficacious. CAM use was frequently driven by family pressure and desperation for relief. The influence of family and peers on CAM use among South Asian immigrants suggests that in this population, CAM use may be less about patient autonomy in exercising medical pluralism and instead be influenced more by family pressure and advice [38].

Thus, CAM use among the South Asian diaspora has many aspects relating to maintaining traditions, the influence of family on an individual’s decision-making, health beliefs, affordability, and length of stay in the country, among other factors. To our knowledge, there are no studies about US South Asians that focus on perspectives and factors affecting CAM use beyond quantitative measures and that focus on youth. This study seeks to contribute to the knowledge about the motivators and practices of CAM use among South Asian youths. Frequently, youths may bridge cultures, be involved in decision-making for older family members as well, especially in instances of immigrant families that may have some members with low English proficiency and lack of familiarity with the US health system. Thus, knowledge about CAM use among this population can help clinicians and other healthcare workers to serve the needs of South Asians in a culturally competent manner.

Methods

After approval from the IRB of California State University, East Bay, a public university in the US (IRB# CSUEB-IRB-2018–165-F.), we recruited students on campus through word of mouth, flyers, and emails sent to student groups and departments with a relatively large number of South Asian students. To be eligible to participate in the focus group discussions, individuals were required to be at least 18 years of age and self-identify as being from South Asia or their families were originally from South Asia.

The first author, a female, Hindu, cisgender PhD-trained researcher born and raised in India developed a focus group guide based on a literature review of concepts and issues relevant to healthcare decision-making among South Asians and minorities. Three undergraduate research assistants were trained in focus group observation and coding qualitative data. After explaining the purpose of the study and obtaining informed consent, the lead author moderated the focus group discussions (FGDs), while the research assistants attended in pairs and noted the interactions, non-verbal communication, and other relevant observations. One group consisted of only males and one group of only females, while the remaining eight groups had a mix of males and females. In some groups, participants knew each other and/or the moderator. The research team sought to facilitate an open and rich discussion among participants.

The participants also completed an online demographic survey using Qualtrics [42] before or after the focus group discussion. Microsoft Excel [43] was used to analyze the demographic survey data.

Participants were served refreshments during the FGD and given a $10 incentive in terms of a credit on their student card. The study team debriefed after each discussion, with a focus on the nature of the discussion and the group dynamics. Data collection was continued until saturation was reached, with the team determining that no new information was emerging. The focus group discussions were audio recorded with participant permission. Data were professionally transcribed. The lead researcher checked each transcript for accuracy and corrected errors. Coding was performed in Dedoose, an online software [44]. Thematic analysis was conducted using steps laid down by Braun and Clarke [45]. The steps were developing familiarity with the data through repeatedly reading the transcripts, generating codes, developing and refining themes, and writing the results. Thematic analysis is a versatile approach that can address a range of questions such as people’s views and perceptions, factors that shape specific phenomena, rules, and norms that influence behavior and people’s actions and practices, among others [46]. It is particularly suited to applied health and wellbeing research to identify patterns across the data with respect to the research question [47].

Codes were developed both deductively and inductively upon reading the transcripts, and code definitions were developed. Initially, each student assistant independently coded a separate transcript. The lead researcher coded the same transcript and compared codes with each student to come to a consensus. Subsequent transcripts were coded by two student assistants each (blinded to each other’s work), and disagreements were resolved by a consensus. The codes were revised and merged as needed, and a few new codes were added. All team members wrote memos to aid in recall and analysis.

Subsequently, the codes that were similar were grouped together and developed into potential theme and-sub theme ideas. The lead author noted the themes and sub-themes into a document and pasted the relevant participant quotations under each theme or sub-theme heading. This helped check that the themes reflected the participants’ voices and also helped in the final stage of thematic analysis (writing the results). The lead author drew thematic maps by hand to visualize the linkages between the themes. She re-read the transcripts to understand how the themes matched with the focus group discussions as a whole. Theme names were modified to reflect the meaning that emerged from the participant’s accounts. Referring to the literature on CAM use among minorities further helped contextualize the themes and finalize the theme titles. Finally, the themes were compared across all transcripts and reviewed by the lead researcher and one student assistant. Trustworthiness of the study was supported by peer debriefing and reflexivity.

Results

Ten focus groups were conducted with thirty-six participants (undergraduate or baccalaureate students of South Asian origin, both US-born and immigrants). The average duration of the discussions was approximately 54 min. Table 1 describes the study participants’ demographics. Nearly half of our sample was born in India (17), followed by the USA (12), Nepal (3), Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Fiji islands (1 each).

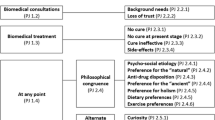

Many participants shared that they consulted physicians only for acute medical problems and instead relied on CAM as the first line of treatment. A wide variety of CAM use was reported, such as Ayurveda, homeopathy, yoga, chiropractic, spiritual healing, acupuncture, water therapy, and home remedies. Examples of home remedies mentioned by participants included the use of ginger, cloves, turmeric, honey, teas, and saline water, based on the belief about inherent healing qualities of food. Data analysis revealed mostly positive views towards CAM use. CAM was believed to be safe, natural, frequently low cost, and free of side effects. Additionally, motivators for CAM use were older family members and cultural norms that favored CAM use. Many participants practiced medical pluralism by combining CAM with other therapies. We did not see any differences in responses about attitudes towards CAM use among participants born in the USA versus other countries. The themes are discussed below along with illustrative quotes.

Intergenerational Use of CAM

Cultural Norm

CAM use was described as part of the cultural norm for maintaining health and curing illnesses and mostly passed down the generations from grandparents and parents to the participants. Some participants shared how their elders had been using CAM, since the time they did not have access to doctors and encouraged the youngsters to use CAM. CAM use was described as a cultural feature. “I feel like culture, a lot, has been a constant thing, like home remedies and stuff like that”, Participant 11, FGD 2. CAM use was also linked with cultural values of obeying elders. As one participant said, “We like to obey our parents, because they are more experienced. Generally Indians from childhood only we used to listen to our parents. So that’s the main reason [for using CAM].”, Participant 27, FGD 7.

Intergenerational use also led to trust in home remedies. As one participant said, “I was going to say turmeric is like … They’d say it would solve everything. That’s like my grandma’s perspective. Drink it or put it on or sniff if you can…That’s an exaggeration. And I think research has also shown that it’s effective in terms of treating inflammation.”, Participant 30, FGD 8.

Many participants explained that after coming to the USA or starting college, they tried to follow the same remedies they had seen their parents use. CAM was often the first line of treatment. One participant said, “For the common cold, my mom always gives me hot water with ginger and honey instead of medicine first. If that’s not working, then the medicine comes. I do the same”, Participant 18, FGD 4.

However, with globalization, some changes were evident such as a few participants sharing that they learnt about CAM themselves from sources such as the internet, radio, television, or their friends, instead of their families. Two participants stated that they began to appreciate the benefits of CAM more as they grew older, with one describing her feelings as a child that her friends would judge her if they saw her using CAM.

“…growing up I was a bit kind of critical of some of these methods ‘cause to me … I grew up here and I would see some of this and be like, “Well, that’s not what most of my friends at school would do. They’re going to ask me about this,” like, “What is this,” you know? As I got older, I started to really see some of the value in it and personally I’ve really benefited from it.” Participant 30, FGD 8.

Intergenerational Conflict

There was intergenerational conflict as well relating to CAM use. Some youths stated that they opposed the use of CAM remedies by older family members. They believed that western medical advice (e.g., managing insulin levels for diabetes than CAM remedies) should be followed. Some were accepting of CAM use as a complement to allopathic medicine, depending on the condition. Two especially critiqued the religious/spiritual practices such as visiting shrines, religious healers, and using amulets for healing in their home countries (Pakistan and Nepal, respectively) as ineffective. One participant shared an instance where she stopped her mother from self-medicating through home remedies when it worsened the situation.

“My mom, she has tooth ache sometimes and she uses the cloves, she put it in her mouth and she was like ‘they stop pain.’ Then the next thing you know she had like a blister and she kinda messed it up more and then she had more pain and she was like ‘I’m having pain.’ I was like ‘that’s it, we’re not going to let you use those anymore.’” Participant 23, FGD 6.

Motivations for CAM Use

In addition to cultural norms and intergenerational family influence, there were several individual-level factors that motivated CAM use. These are presented below.

Natural Care

The overwhelming reason for use of CAM was stated to be the belief that CAM was “natural” and more effective than allopathy. One participant stated, “if you can do it naturally kind of in a holistic way, would rather do that. For my family, medication is kind of like the last resort, if you’re really, really sick.”, Participant 5, FGD 1.

Belief in the effectiveness of CAM was based both on participants’ own experiences and that of others. Participants additionally believed that CAM would not trigger allergies, provide a long term solution, and not cause overdose or addiction. Participants shared examples of self or family wherein allopathy had caused allergic reactions or use of CAM (e.g., homeopathy) had provided permanent relief from a condition, strengthening their motivation for using CAM.

Cost Considerations

CAM use was also described as linked with “socio economics” and being “ (financially) responsible” with some participants mentioning that home remedies especially were preferred because they were cheaper than allopathy. One participant said, “Some don’t have health insurance, so they really don’t have the money to pay for it, so they got to go for home remedies and they feel like once they get that prescription they’re going to get addicted to it and it’s going to get worse. That’s what some Indian people think most of the time.”, Participant 13, FGD 3. Another participant said, “You don’t give anything just to have natural remedies.”, Participant 25, FGD 7. International students especially mentioned problems with health insurance (e.g., the high cost of drugs in the USA, as compared to South Asia) and that in contrast, home remedies were inexpensive.

Reluctance to Use Pain Medication

CAM use was also linked indirectly with a reluctance to use pain medication. For example, some participants mentioned that they were taught growing up that pain was natural and thus it could be healed using home remedies instead of allopathy. Some mentioned that they preferred to skip using the pain medication they had by trying CAM. One participant shared that in case of pain, “I would rather not take medicine. I would tend to like drink warm water with honey, or whatever herbal things, but not to take medicine.”, (Participant 7, FGD 1).

Another provided a context for using CAM by explaining that allopathy does not provide a root cause to the solution of pain. She said,

I personally try to avoid pain killers too. It’s really bad for your kidneys and I try to avoid them as much as possible. I take a little bit more philosophical approach, where my body is trying to tell me something, it’s just better to feel it through and see what’s going to happen. To be honest doctors don’t really understand pain. They don’t understand where pain is coming from and why. Sometimes most of the pains that people experience is blamed on allergy or blamed on migraine or vertigo, nobody knows where it’s coming from. So, I don’t see why I should suppress a symptom rather than suppressing the cause which they don’t really know. Participant 34, FGD 9.

Medical Pluralism

The elements of medical pluralism described by our participants include using CAM as the first line of treatment before trying allopathy, using CAM for symptom management, using CAM to complement other therapies, and being influenced by social networks in countries of origin outside the USA to mix CAM with conventional treatment.

First Step in Treatment

A large number of participants stated that the first choice for treatment especially for “minor” issues (e.g., cold, cough, and aches) were home remedies. Participants shared accounts wherein they or their family members had waited several weeks before seeking allopathic treatment, either self-medicating or waiting for the issue to resolve on its own. This could have negative consequences as exemplified by one participant who said she waited a long time to get treatment while suffering from dengue and her condition became serious.

Symptom Management

CAM was frequently used in the participants’ families to manage symptoms of chronic diseases. Some alluded that their family members had turned to pluralistic care when allopathy did not cure them. For example, one participant mentioned, “ …[participant’s mother] was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis which is a progressive, neurodegenerative disease that she still has. But, the symptoms, they haven’t really subsided, that’s not really the correct word, they’re stagnant. Due to that, like my mom has regular MRIs, goes to the doctor regularly, sees like, her pain management doctor. Like, she’s doing a lot holistic things: acupuncture, chiro, things like that.”, Participant 24, FGD 6.

One participant shared that she used pain management therapies influenced by her parents’ advice, though their beliefs were mutually in conflict.

Participant: So, my father believes in allopathic treatments, and my mother she has a Masters in like Yoga Science and natural science which is natural therapy. So, I get the best of both worlds where my dad is telling me to pop the pill and then my mum is like use this hot water bag, use this bowl of herbs. Do this. Do that. Massage this finger…Yeah. This finger, that finger. Give me the, using these needles, acupuncture or acupressure, and then that’s how we do pain management usually. Sometimes it’s like, it depends on the water, the hot cold water treatment where you dip your hand and legs and it depends on like blood flow and …

Moderator:So it’s like a mix of techniques for you?

Participant 34:“Mix of techniques, yes.” Participant 34, FGD 9.

Complementary Medicine

While a few participants shared accounts of family members using CAM exclusively and shunning allopathy, most shared that CAM use did not preclude the use of allopathic medicine. CAM use complemented allopathic treatments in many instances. One participant mentioned that CAM use in place of allopathy for conditions such as diabetes would lead to serious consequences but that CAM could be used as a supplement. “It’s better to take the medicine and then try that as an alternate, like with it, like additional or supplement, but don’t go for that alone. You still need to take prescriptions because those are really going to help you long-term.”, Participant 12, FGD 3.

Transnational Influence

Transnational connections with families in South Asia also influenced medical pluralism. Some participants relied on allopathic medicine in the USA, but added CAM remedies after acquiring them in their countries of origin. For example, one participant shared that her father who suffered from multiple chronic health conditions, acquires Ayurvedic medicine when he visits his family in India and starts using those as well without medical supervision.

“…for my dad, he’s been struggling so long with his health issues that he’s tried … So, he flip flops between western and eastern medicine. He’ll be on diabetes medicine… and then he’ll go to India and get Ayurvedic medicine and come back with all this Ayurvedic medicine, and then he’ll flip flop in between…” Participant 11, FGD.

Discussion

Non-Western medical approaches are an important component of illness recovery and health maintenance for many South Asians. CAM use continues to be popular with South Asian youths in our study who relied on traditional knowledge as well as sought information about CAM from sources such as the internet and friends. A preference for “natural” care, trust in holistic medicine, cost considerations, convenience, absence of side effects, and cultural practices were the main drivers for CAM use, especially for minor health issues. Interestingly, even therapies that did not originate in South Asia such as acupuncture and chiropractic care were mentioned by a participant as being used in her family. The use of CAM was primarily related to participants’ belief in its efficacy and “natural care”, even if the original impetus for use came from participants’ upbringing or family.

The literature on CAM use among US South Asians is very limited [13, 14] and quantitative in nature. Our study is one of few in recent years to qualitatively explore the views of South Asians in the US on CAM use. Adult children are often involved in decision-making for healthcare for older family members in South Asian families. Existing studies are survey-based, not recent and report correlates of CAM use but do not explore the perspectives behind such use. Given the growing number of South Asians in the USA, this study thus makes a useful contribution for clinicians and other healthcare providers who presently serve or will work with South Asians in the future.

Participants expressed a preference for CAM utilization for ailments such as colds, coughs, and upset stomachs, consistent with the literature [14]. They were thus continuing patterns seen in South Asia as the first recourse for minor ailments [20, 36]. This included the ease of utilizing herbs or foods that are already on hand [29] and following the advice or pressure from family [38]. However, some of our participants also sought CAM use themselves, by finding information through the internet or friends. Thus, not all CAM use among this population is family-influenced, as there are instances of autonomous decisions to use CAM. This also highlights the importance of social networks that might be the only source of support for immigrants and their source of health information instead of medical professionals. The fear of debt and not knowing what services were covered by health insurance were particularly important for international students.

Like other South Asians, our participants also engaged in pluralistic care [4, 18]. Our findings highlighted a proclivity among individuals to use a combination of alternative remedies and allopathic treatments in order to attain a balance between relief and safety [25, 48,49,50]. The popularity of this attitude and approach is therefore of great import. For example, there are limitations and drawbacks associated with CAM usage (e.g., deferred diagnosis and the potential for polypharmacological interactions) which has been reported in other Asian populations [51] that carry risk of harm. Due to CAM being frequently viewed as harmless [52], its use is sometimes not reported at the time of allopathic treatment seeking. These realities surrounding CAM and medical pluralism thus hold significant implications for patient safety and appropriate education. Our participants being younger had fewer health issues and had not sought care much from US providers. Therefore, the question of whether they reveal CAM use to US providers did not emerge in the discussions.

The strengths of our study include insights from participants that were born in the USA as well as internationally-born participants. The focus group discussion format allowed participants to share and discuss their views about CAM. They were able to draw upon their own experiences, their families’, and in the case of international students, discuss additional information about the impact of insurance and their circumstances on using CAM. The limitations of this study include that as for all qualitative studies, the results are not generalizable and not intended to be representative. In order to protect participants’ privacy in a focus group discussion setting, we did not probe for personal health information beyond what was voluntarily shared by participants. Thus, we could not enumerate for example how many of the participants had or were currently using CAM.

Implications

The World Health Organization has recommended adding CAM into conventional health service delivery systems [3]. South Asian youths living in the USA that participated in this study still embrace CAM despite being exposed to Western healthcare practices in the USA and/or their countries of origin. This suggests that adoption of patient-centered approaches can be enhanced through understanding and increasing provision of CAM [2]. With clinicians seeking to become more culturally competent, research is needed to understand CAM further. The US.

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) recognizes the need for clinical and implementation research on CAM so that it can be integrated into health delivery systems [53]. Its recommendations include step-wise research from efficacy to effectiveness, dissemination, and implementation [53]. Limited dissemination of existing evidence on CAM is a major barrier in including this in conventional care because clinicians and policymakers may perceive this as absence of supporting evidence [53].

More studies on effectiveness of CAM can build the case for enhancing coverage of CAM through health insurance in Western countries. Some insurance providers such as Kaiser Permanente do provide limited coverage for some CAM therapies (e.g., acupuncture and chiropractic care). Second, it is important to dispel the common myth that CAM is inherently safe, especially because of CAM use being combined with other therapies. CAM products that contain active substances that are pharmacologically strong could potentially be harmful when used incorrectly or used simultaneously with other medications [2, 36]. Clinicians need to understand CAM more to reduce the chances of adverse interactions. They also need to proactively ask their patients about CAM use, especially minority populations that use CAM in their countries of origin and educate them about their potential risks. Patients may be hesitant to reveal CAM use to providers especially if they are of a different background, given the history of colonialism and the spread of biomedicine. Clinicians should thus be careful about the nuances of patient-provider communication and sensitively elicit these care preferences. Third, it should be noted that South Asians may delay seeking conventional care because of self-treatment with CAM. This highlights the importance of spreading awareness about the risk of self-treatment in some cases and seeking timely care. This can help patients benefit from CAM while avoiding behaviors that may be risky such as self-treatment or delaying care.

As the number of immigrants in the USA increases, healthcare providers will need to serve a diverse population that may bring other healing traditions that fall outside conventional biomedicine. This was a small, exploratory study on perspectives on CAM use among US South Asian youths. There is a need for further research with larger samples that are diverse in terms of age, health conditions, and socioeconomic circumstances, among others. Understanding South Asians’ preferences regarding CAM and investigating the impact of factors that affect CAM including but not limited to health insurance may help health practitioners to provide better care for persons of South Asian origin in the USA.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

References

Mora DC, Kristoffersen AE, Overvåg G, Jong MC, Mentink M, Liu J, Stub T. Safety of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatment among children and young adults who suffer from adverse effects of conventional cancer treatment: a systematic review. Integr Cancer Ther. 2022;21:15347354221105564. https://doi.org/10.1177/15347354221105563.

Ali N, Gambles MH. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use among South Asian patients with cancer in Britain. Divers Equal Health Care. 2005;2(1):41–5.

WHO (2013). WHO traditional medicine strategy 2014–2023. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/92455/9789241506090_eng.pdf

Broom A, Wijewardena K, Sibbritt D, Adams J, Nayar KR. The use of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine in Sri Lankan cancer care: results from a survey of 500 cancer patients. Public Health. 2010;124(4):232–7.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the American Public. Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2005. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83804. Accessed 02 Feb 2023

Khatri A, Sinha AK. Medical pluralism in India and AYUSH: a review. Integration. 2011;28:29.

Sudarsan I, Hoare K, Sheridan N, Roberts J. South Asian immigrants’ and their family carers’ beliefs, practices and experiences of childhood long-term conditions: an integrative review. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(7):1897–908.

SAALT. Demographic snapshot of South Asians in the United States. April 2019. https://saalt.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/SAALT-Demographic-Snapshot-2019.pdf. Accessed Dec 10, 2022

Pew Research Center. Key facts about Asian origin groups in the U.S. April 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/04/29/key-facts-about-asian-origin-groups-in-the-u-s/. Accessed May 3, 2023

Khosla N, Washington KT, Regunath H. Perspectives of health care providers on US South Asians’ attitudes toward pain management at end of life. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33(9):849–57.

Khosla N, Washington KT, Shaunfield S, Aslakson R. Communication challenges and strategies of US health professionals caring for seriously ill South Asian patients and their families. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(6):611–7.

Tanaka MJ, Gryzlak BM, Bridget Zimmerman M, Nisly NL, Wallace RB. Patterns of natural herb use by Asian and Pacific Islanders. Ethn Health. 2008;13(2):93–108.

Satow YE, Kumar PD, Burke A, Inciardi JF. Exploring the prevalence of Ayurveda use among Asian Indians. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(10):1249–53.

Misra R, Balagopal P, Klatt M, Geraghty M. Complementary and alternative medicine use among Asian Indians in the United States: a national study. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(8):843–52. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2009.0517.

Thakar VJ. Historical development of basic concepts of Ayurveda from Veda up to Samhita. AYU (An international quarterly journal of research in Ayurveda). 2010;31(4):400.

Davey S. Unintended consequences of regulating traditional medicine. WHO-South East Asia J Public Health. 2013;2(3):131.

Khalikova VR. Institutionalized alternative medicine in North India: plurality, legitimacy, and nationalist discourses (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pittsburgh). University of Pittsburgh ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2017. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/openview/48c53331fbbb51a204065642748de6f2/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750.

Durkin-Longley M. Multiple therapeutic use in urban Nepal. Soc Sci Med. 1984;19(8):867–72.

Shankar D. Health sector reforms for 21st century healthcare. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2015;6(1):4.

Srikantha N, Bhat S, Singh A, Singh R. Healthcare seeking attitude and utilization of traditional medicine in India-an overview. World J PharmaCeut Res. 2015;4(7):722–38.

Aftab W, Shipton L, Rabbani F, Sangrasi K, Perveen S, Zahidie A, Naeem I, Qazi S. Exploring health care seeking knowledge, perceptions and practices for childhood diarrhea and pneumonia and their context in a rural Pakistani community. BMC Health Ser Res. 2018;18(1):1.

Ahmed J, Raynes-Greenow C, Alam A. Traditional practices during pregnancy and birth, and perceptions of perinatal losses in women of rural Pakistan. Midwifery. 2020;1(91):102854.

Kanimozhi T, Hindu K, Maheshvari Y, Khushnidha YG, Kumaravel M, Srinivas KS, Manickavasagam M, Mangathayaru K. Herbal supplement usage among cancer patients: a questionnaire-based survey. J Cancer Res Ther. 2021;17(1):136–41.

Sheehan HE. Medical pluralism in India: patient choice or no other options? Indian J Med Ethics. 2009;6(3):138–41.

Chacko E. Culture and therapy: complementary strategies for the treatment of type-2 diabetes in an urban setting in Kerala. India Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(5):1087–98.

Mohanty PC, Sharma K. Households’ responses on medical pluralism: dynamics and determinants of access to traditional medicines in India. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;1(12):100880.

Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Utilization of complementary and traditional medicine practitioners among middle-aged and older adults in India: results of a national survey in 2017–2018. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2021;21:1–1.

Jangra I, Dubey AK, Arora E, Peerzada BI. Self-medication with modern and complementary alternative medicines in patients with chronic pain. J Res Pharm Pract. 2022;11(1):19.

Pandey L, Pasricha R, Joseph D, Ahuja R, Yanthan Y, Garg PK, Gupta M. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with cancer in a sub-Himalayan state in India: an exploratory study. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2021;12(1):126–30.

Thorsen RS, Pouliot M. Traditional medicine for the rich and knowledgeable: challenging assumptions about treatment-seeking behaviour in rural and peri-urban Nepal. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(3):314–24.

Das TK, Choudhury DS. Are ‘complementary and alternative medicines’ alternative to conventional medical system? An Econ Eval Appl Econ Lett. 2007;14(9):697–700.

Choi SJ, Kunwor SK, Im HB, Hwang JH, Choi D, Han D. Traditional and complementary medicine use among cancer patients in Nepal: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022;22(1):70.

Lhamo N, Nebel S. Perceptions and attitudes of Bhutanese people on Sowa Rigpa, traditional Bhutanese medicine: a preliminary study from Thimphu. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2011;7(1):1–9.

Fleming E, Gillibrand W. An exploration of culture, diabetes, and nursing in the South Asian community: a metasynthesis of qualitative studies. J Transcult Nurs. 2009;20(2):146–55.

Agu JC, Hee-Jeon Y, Steel A, Adams J. A systematic review of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine use amongst ethnic minority populations: a focus upon prevalence, drivers, integrative use, health outcomes, referrals and use of information sources. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;1(21):1137–56.

Rao D. Choice of medicine and hierarchy of resort to different health alternatives among Asian Indian migrants in a metropolitan city in the USA. Ethn Health. 2006;11(02):153–67.

Subedi R, Kaphle S, Adhikari M, Dhakal Y, Khadka M, Duwadi S, Tamang S, Shakya S. First call, home: perception and practice around health among South Asian migrants in Melbourne. Australia Aust J Prim Health. 2022;28(1):40–8.

Rhodes PJ, Small N, Ismail H, Wright JP. The use of biomedicine, complementary and alternative medicine, and ethnomedicine for the treatment of epilepsy among people of South Asian origin in the UK. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8(1):1–4.

Ismail H, Wright J, Rhodes P, Small N. Religious beliefs about causes and treatment of epilepsy. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(510):26–31.

Felicilda-Reynaldo RF, Choi SY, Driscoll SD, Albright CL. A national survey of complementary and alternative medicine use for treatment among Asian-Americans. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020;22:762–70.

Bhamra SK, Slater A, Howard C, Johnson M, Heinrich M. The use of traditional herbal medicines amongst South Asian diasporic communities in the UK. Phytother Res. 2017;31(11):1786–94.

Qualtrics (2005). Provo, Utah, version Nov 2022. Available at: www.qualtrics.com

Microsoft Corporation. (2018). Microsoft Excel. Retrieved from https://office.microsoft.com/excel

Dedoose (2021). Version 9.0.17, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC www.dedoose.com

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Braun V, Clarke V. Understanding TA. Available at: https://www.thematicanalysis.net/understanding-ta/ Accessed May 28, 2023

Braun V, Clarke V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2014;9:1. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.26152.

Jennings HM, Merrell J, Thompson JL, Heinrich M. Food or medicine? The food–medicine interface in households in Sylhet. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;5(167):97–104.

Albert S, Nongrum M, Webb EL, Porter JD, Kharkongor GC. Medical pluralism among indigenous peoples in northeast India-implications for health policy. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20(7):952–60.

Doron A, Broom A. Health and healing in South Asia. South Asian Hist Cult. 2010;1(2):193–8.

Coronado G, Chio-Lauri J, Cruz RD, Roman YM. Health disparities of cardiometabolic disorders among Filipino Americans: implications for health equity and community-based genetic research. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;26:1–8.

Krupa NC, Thippeswamy HM, Chandrashekar BR. Patterns of usage of complementary and alternative medicine among adults visiting health care centers in Mysuru, India: a questionnaire-based survey. Holist Nurs Pract. 2021;35(4):199–205.

Chung VC, Ho FF, Lao L, Liu J, Lee MS, Chan KW, Nilsen P. Implementation science in traditional, complementary and integrative medicine: an overview of experiences from China and the United States. Phytomedicine. 2023;109:154591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154591.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr J P Leider and Dr Supriya Misra, for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

Funding

Data collection for this study was funded by an internal grant from California State University, East Bay.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first author conceptualized the study, did participant recruitment, data analysis, and writing. The second and third authors contributed to writing the literature review and discussion sections.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the IRB of California State University, East Bay.

Consent to Participate

All the participants were explained about the study verbally, and they completed a written informed consent process before participating in the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable; information presented is deidentified.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Khosla, N., Hahn, L. & Tran, C. US South Asian Youths’ Perspectives on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM). J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 11, 2044–2054 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01672-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01672-9