Abstract

Ethnic minority populations have been identified as high users of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine (TCAM). This paper reports the systematic review of TCAM use amongst ethnic minorities. A comprehensive literature search was conducted in Ovid, PubMed and CINAHL. Included studies were original, peer-reviewed, English language articles with the primary focus on TCAM use amongst ethnic minority populations. A total of 17 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review. A considerable level of TCAM use was observed amongst ethnic minority populations usually attributed to its perceived safe and natural properties. Ethnic minority populations predominantly used TCAM concurrently with conventional medicine and primary TCAM referral sources were family and friends. A substantial level of TCAM integration with conventional medicine is common practice amongst these populations and the lack of disclosure about TCAM use raises an important area for further research inquiry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, there is an exponential increase in the use of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine (TCAM)—practices and products which can be indigenous (traditional medicine) and/or exotic (complementary and alternative medicine) to the user and are not traditionally associated with conventional medical practice or curriculum including traditional herbal medicines, naturopathy, yoga, chiropractic, acupuncture and massage amongst others [1]. TCAM is used for both physical and emotional conditions [1, 2] and for the management of common illnesses including pain (musculoskeletal), depression and anxiety [1, 3]. TCAM has been identified as popular amongst those looking to manage their quality of life and treat symptoms relating to chronic illnesses such as liver disease, lung disease, cardiovascular disease and cancer [1, 4] For both chronic and acute illness, TCAM may offer symptom relief, a reduction in side effects and interim hope and comfort [1, 5].

Substantial TCAM use is evident across most socioeconomic groups in most cultures and amongst ethnic minority populations—groups of individuals with racial, national, cultural and/or religious origins dissimilar from the dominant population of the country where they reside—and constitutes a significant health care resource [6, 7]. Many TCAM are practices grounded in the traditions, cultures and beliefs of ethnic minority communities, originating in their country of heritage [8,9,10]. During the migration process, migrants tend to transport TCAM practices to their host countries, increasing their likelihood of employing TCAM approaches before or at least alongside their use of conventional medicine in their new adoptive country [9]. As such, ethnicity and culture play a significant role in influencing the rates, types and patterns of TCAM use [10, 11]. Ethnic minorities face a number of cultural, communication, behavioral and economic barriers to accessing health services often with adverse effects on their quality of life and overall health and well-being [9, 10]. These challenges are further exacerbated by cultural values and beliefs about healthcare help-seeking amongst these communities [12, 13], thereby making ethnic minorities an important target group for research enquiry and health care policy.

While there has been some early work on the utilisation of TCAM specific to ethnic minorities [9] there has been no comprehensive review on contemporary literature regarding TCAM use amongst ethnic minority populations. Given the wider challenges faced by ethnic minorities regarding accessing health care services [9, 10] and the potential direct and indirect risks associated with TCAM use alongside conventional medical care [14] it is imperative to understand the behaviours, communication and decision-making around TCAM use. This is essential to help inform the broader delivery of culturally sensitive health care to meet the needs of ethnic minority populations. In direct response to this significant research gap, this review aims to identify the prevalence, frequency and specific TCAM use as well as motivations for TCAM use in ethnic minority populations based on recently published research evidence from 2006 to 2017.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (the PRISMA statement) [15].

Study Design

A systematic review was undertaken to explore and synthesise findings from previous original research regarding the use of TCAM amongst ethnic minority groups. For the purpose of this review an ethnic minority is defined as a community/population of racial, national, cultural and/or religious background that differs from the dominant population of their resident country. Some disparate attributes of ethnic minorities may be demonstrated in their ethical values, distinct customs and beliefs, languages spoken, lifestyle choices, health choices, dress sense and food preferences which are adopted by ethnic group members. For heuristic reasons, we did not consider individuals that were indigenous or had historical ties to the country/territory they lived in as ethnic minorities. A paper was deemed to be reporting on use of TCAM in an ethnic minority population if the focus of the sample fitted the definition above or was defined as TCAM and/or an ethnic minority by the researchers/authors. This review involved a comprehensive database search, article screening and selection, appraisal of evidence, data extraction, summary and synthesis of findings.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted from October 2016 to June 2017 to identify peer-reviewed literature published in English using the following databases: Ovid (Medline), PubMed and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). The Cochrane library was excluded in this review as the focus was not on efficacy. Keywords and Boolean operators used during the search include: (‘complementary medicine’ OR ‘alternative medicine’ OR ‘traditional medicine’ OR ‘complementary therapies’ OR ‘medicine, traditional’) AND (‘culturally and linguistically diverse’ OR ‘ethnic minority*’ OR ‘minority groups’ OR ‘vulnerable populations’ OR ‘non-English speaking background’ OR ‘migrants’). These terms were used as keywords and also matched to medical subject headings (MeSH). Reference lists of relevant articles were searched to identify further papers.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

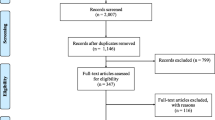

In order to determine the relevance of each article for the review, screening was conducted in accordance to specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Essentially, articles for inclusion had to reflect TCAM as their primary research focus as either addressed in the aim, objective, and methodology or listed as a primary outcome measure and not merely a finding amongst others. Table 1 below highlights the inclusion and exclusion criteria employed in the review. Article screening and selection process are shown in Fig. 1.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data were extracted by the first author (JA) and reviewed and verified by a second author (JA). Discussion was used to reach consensus in case of any discrepancies. All articles were imported into EndNote X7 and duplicates were removed. Initial selection of articles occurred by screening titles and abstracts and some articles were excluded for the following reasons: TCAM was not the primary focus of the paper, outcomes were irrelevant to the study objectives, full text unavailability and articles that were not original research. Full texts of the remaining articles were screened for eligibility and the final selection of articles advanced to the critical appraisal phase.

Critical Appraisal of Articles

Quality appraisal tools for qualitative [16] and quantitative [17] studies were used in this review accompanied with guidelines to ensure appropriate application of the tools. These guidelines were modified by inserting the word ‘TCAM’ where necessary to correspond with our study (Table 2)—this follows a similar modification process undertaken in a previous study [18].

Qualitative studies identified as meeting the inclusion criteria of our review were appraised using guidelines by Higginbotham et al. [16] that assessed the following 10 categories of interest: study purpose, rationale, conceptual framework, ethical implications, sampling strategy, data collection, data organisation, data analysis, reliability and validity, and conclusion (Table 3).

Quantitative studies that met the inclusion criteria were critically appraised using the McMasters University critical appraisal tool—a tool suited to appraising the methodological quality of any type of quantitative study [17]. In line with this tool, the categories examined for each quantitative paper were: study purpose, literature review, study design, study sample, outcome measures, intervention, data analysis, result, dropouts or exclusions, clinical importance, conclusion and limitations (Table 4). Categories in the appraisal tool that were only relevant for clinical trials (e.g. contamination and co-intervention) were removed.

After articles were critically appraised, extraction, summary and synthesis of data occurred using the NVivo 11 software, a data organisation and management software. Data extraction and summary was carried out using a systematic review technique. Findings were summarised and categorized in a tabular form including; study location, methodology, demographics, aims/objectives and outcomes relevant to the review (Table 4). Using an inductive approach, an investigator (JA) identified recurrent concepts and ideas from research outcomes by reading through each article repeatedly and coding them to different nodes in NVivo. These codes were then categorised into key themes (Table 5).

Results

A total of 17 articles met the study inclusion criteria for analysis. A summary of the literature search process is shown below in Fig. 1.

Quality Appraisal

Results from quality appraisal of all studies are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Appraisal of qualitative studies (n = 6) using the Higginbotham et al. guidelines [16], revealed that the majority (n = 5) were adequately designed and clearly addressed the study purpose, rationale, ethical considerations, data collection methods and data analysis procedures [19,20,21,22]. However, a number of these studies failed to identify conceptual frameworks, which were applied [22, 23], procedures used in data management [20,21,22,23] and threats to reliability and validity [20, 23]. For quantitative studies using the McMasters critical appraisal tool [17], poorly reported components include dropouts/exclusions [8, 10, 24,25,26], clinical importance [26,27,28], intervention descriptions [26, 29] and limitations [27, 28].

Most articles included in the review did not address measures employed to control for bias. The lack of detail on data management procedures by all qualitative studies in this review with the exception of George et al. [19] may be indicative of outcome reporting bias. Without proper data management there is no guarantee that results reported followed the study protocol or whether selective omission occurred in reporting [30]. Some quantitative studies failed to report on dropouts and exclusions, which in turn may affect selection bias especially in the advent of unequal loss of participants (attrition bias) [31, 32]. However, well-reported study elements across all included quantitative studies include study purpose, literature review, research design, initial sample size and description, validity and reliability with the exception of Thorburn et al. [24], data analysis procedures, results and conclusion. Overall, the critical appraisal indicated that the included articles constitute rich sources of data, as such all articles were included for the review.

Overview of Studies

The review identified 12 papers reporting relevant data using quantitative methods and five reporting relevant data drawn from qualitative research. The most frequently utilised data collection methods were face–face, self-administered, telephone and//or computer assisted surveys (n = 12), followed by focus group discussions (n = 3) and in-depth interviews (n = 3) (Table 5). Studies were predominantly conducted in the US (n = 12), other study regions were Vietnam, UK, South Korea, Malaysia, Germany and Canada (n = 1 each). The reported sample sizes ranged from a small focus group study of n = 12 conducted amongst Caribbean ethnic minorities living in the United States [22] to a National Health Interview Survey sample of n = 34,483 which oversampled black, Hispanic, and Asian populations [25]. Amongst the wide range of TCAM modalities reported in the literature reviewed, the most frequently cited were: herbal medicine, acupuncture and chiropractic respectively. In this review, TCAM was used in the treatment and management of both acute illnesses (cold, fever, coughs and stomach pains) and more chronic conditions (cancer, hypertension, diabetes, asthma). Most participants integrated TCAM and conventional medicine for health and wellbeing (Table 5).

Key Themes from Data Synthesis

Six themes resulted from our data synthesis including: relationship between ethnicity and TCAM use; prevalence and modalities used; drivers of TCAM use; TCAM and conventional medicine integration; perceived health outcomes from TCAM use; and TCAM referral and information sources (Tables 5, 6).

Relationship Between Ethnicity and TCAM Use

Belonging to an ethnic minority group was an indicator of increased TCAM-use and some studies found a higher likelihood of TCAM use amongst ethnic minorities compared to their non-ethnic minority counterparts e.g. non-Hispanic Whites and non-migrants [6, 10, 21, 23]. However, this finding was not consistent throughout the reviewed literature as there were some studies, all conducted in the US (n = 3), that reported no significant relationship between ethnicity and TCAM use and found US-born citizens and non-Hispanic whites to have higher TCAM usage than Asians, Hispanics and Blacks [9, 10, 25].

Prevalence and Modalities Used

Many of the included studies reported on the prevalence and type of TCAM used by different ethnic minority populations. Of the 17 papers reviewed, 14 reported prevalence rates of TCAM use amongst their study populations ranging from 14.9 to 100% of study samples/participants. The highest prevalence rate (100%) reported in the literature reviewed was from a study examining low-income African-American (AA) adults in the US George et al. [19]. A prevalence rate of 79.4% was reported from a study [28] which explored TCAM use in East Malaysia amongst Malay, Sabah natives, Chinese and Indian populations. The lowest prevalence rate (14%) of TCAM use by an ethnic minority population was from a study that explored the relationship between Chinese Canadian ethnicity and the use of TCAM [8]. Although the prevalence rate was low at 14%, this study reported a greater likelihood of TCAM use amongst Chinese Canadians than non-Chinese Canadians. The reviewed literature reported some modalities as particularly popular amongst certain ethnic population groups in particular settings. For example, one study identified Ayurveda and homeopathy as most popular when compared to other TCAM modalities amongst Indians and other Asians in the US [20], while another paper reported acupuncture as the preferred TCAM modality choice amongst Mongolians living in South Korea [6] and a third paper recorded preference for use of herbs amongst the Chinese community in the US [10].

Drivers of TCAM Use

Many of the studies identified ethnic minority populations as more accustomed to non-biomedical approaches to healthcare (TCAM) than non-ethnic minority populations, due to a perception of TCAM as safer, more effective and as ’natural’ in approach [6, 19,20,21, 23]. The perceived safe and natural properties of TCAM alongside the experience of symptom relief have been identified as motivators for TCAM use amongst low income African American adults [19].

Level of confidentiality and stigmatisation were other drivers of TCAM use as seen in immigrant women from the Caribbean living in the US who expressed privacy concerns and recounted experiences of stigmatization by conventional medical doctors, which they believed occurred as a result of their accents and ethnic minority status [22]. Some experiences which served as motivations for TCAM use reported by these women were; insufficient patient-doctor consultation time with conventional medical doctors, feeling rushed and the perception of their conventional medical doctors as not focussed or interested in the health or treatment of their children [22].

Another study conducted in the US that analysed data from the Health Care Quality Survey (HCQS) which oversampled African-American, Hispanic, and Asian households also described experiences of stigmatisation and discrimination [24]. The authors reported a significant association between herbal medicine use and discrimination (measured in terms of disrespectful and unjust treatment by a conventional medical doctor) in healthcare as experienced by ethnic minorities [24].

Not all studies included in the review reported a preference for TCAM over conventional medicine by ethnic minorities. One study examined TCAM prevalence and reasons for use by comparing data from oversampled Black, Hispanic and Asian populations and found barriers to accessing TCAM services included a lack of insurance coverage for TCAM services and having a low income which is further accentuated by the high cost of some TCAM services [9]. Overall across most studies in the review, there was a correlation between gender, SES and TCAM use as more ethnic minority females were found to utilize TCAM than males [25, 26, 33] and an ability to afford private insurance coverage increased the likelihood of TCAM use in some studies [10, 20].

TCAM and Conventional Medicine Integration

Generally, a small proportion of ethnic minority populations exclusively utilise TCAM for their health care needs with most using TCAM and conventional medicine concurrently—a phenomenon known as medical pluralism which is common even in countries with well-established health care systems [9, 25].

TCAM was reported as used by ethnic minority populations alongside and concurrent to conventional medicine in a number of the reviewed studies. A study of African American participants found a 93% preference for equal integration of TCAM with conventional medicine used in the treatment of asthma [19], while other research exploring Chinese, Indian, Vietnamese, Malaysian and Filipino ethnic minorities living in South Korea and Malaysia, identified TCAM use as constituting a supplement to conventional care [6, 28].

TCAM disclosure to conventional medicine providers by ethnic minorities was low as reported in four of the 16 papers which examined this issue. TCAM disclosure prevalence rates were reported as 52.2% amongst Chinese, Vietnamese and Filipino ethnic minorities in South Korea [33], 33.4% amongst African American, Asian and Hispanic ethnic minorities in the US [24] and 31.5% amongst Sabah, Chinese and Indian ethnic minorities in Malaysia [28]. Additionally, a study examining HIV positive migrants from Southern Africa living in the UK found that 45% of participants reported using some form of non-conventional medicine and only a few people disclosed their use despite continuing use with conventional medicine, whilst 75% expressed a desire to use non-conventional medicine either as an alternative or in combination with antiretroviral therapy if only they had better access to them [23]. Two reasons for participants’ refusal to disclose their respective TCAM usage were; failure of their conventional medical doctors to ask about any TCAM usage [23] and the fear of condemnation by their medical providers for using TCAM [22, 23]. In addition, migrants from South Africa, Zimbabwe and Zambia in in London, England [23], reported a reluctance to disclose their combined TCAM and conventional medicine use due to a fear that their conventional medical doctors may request they cease TCAM use and they were unwilling to lose the self-perceived health benefits of such use.

Perceived Health Outcome from TCAM Use

Overall, most studies (n = 9) identified high levels of satisfaction amongst ethnic minorities with regards to their TCAM use. Study participants were reported as frequently mentioning associated positive outcomes to TCAM use including: improvement in health status through symptom relief; pain reduction; psychological stability; and increased health promotion and improved physical function [6, 19, 21, 23]. However, perceived effectiveness differed as some Asian Indian participants in a US-based study experienced TCAM use as sometimes effective and ineffective at others [20].

TCAM Referral and Information Sources

The majority of articles reviewed (n = 10) showed that TCAM users within ethnic minority communities access TCAM information from multiple sources, often concurrently, with the most common sources being family and/or friends [5, 19,20,21,22, 28]. The second most popular source of TCAM information was from traditional healers [11, 23, 24, 28, 29, 33]. Other sources of TCAM information cited by ethnic minorities in the review included local markets, TCAM clinics and practitioners, traditional pharmacies, community health workers and the internet. In studies reporting on TCAM information sources, no one information source was exclusively utilised with participants obtaining TCAM supplies and information from multiple sources [5, 11, 19, 20, 22,23,24, 28, 33].

Discussion

This paper reports findings from the first systematic review to explore TCAM use in ethnic minority populations as sourced from contemporary international literature. Analyses of the reviewed literature show that a high level of TCAM use exists amongst people in ethnic minority populations with an evident influence of other socio-demographic factors such as gender and socioeconomic status influencing choice around TCAM use. International studies which have identified independent predictors of TCAM use beyond ethnic minority populations portray similar results in line with our review findings, profiling the average CAM user as female, middle-aged, educated and with higher levels of income than non-CAM users [33,34,35,36,37].

The relationship between TCAM use and ethnicity is of significance to both researchers and those providing care given that only marginal empirical work has explored the predictors and patterns of ethnic minorities’ use of TCAM while national studies have advanced our understanding of TCAM use across more general populations [38, 39]. Our review identifies a positive correlation between ethnicity, type of TCAM used and the decision to use TCAM. These findings are consistent with other studies which have concluded that certain racial/ethnic groups may lean more towards some TCAM modalities than others [38,39,40]. Most studies investigating TCAM use in the UK and US have distinguished between ethnic minority-racial subgroups with some multivariable studies reporting a reduced likelihood of non-white study participants using TCAM compared to white study participants [40,41,42], an increased likelihood of black participants using mind–body therapies and an increased overall TCAM use amongst Asians compared to whites or blacks [43]. Most of these aforementioned studies conducted in the UK and US are limited by the absence of a clear definition of TCAM, the use of surveys administered only in English, the adoption of widely defined categories of ethnicity which limits the heterogeneity of this group and the evaluation of a narrow range of TCAM modalities [33]. Additionally, the findings from most TCAM studies around ethnic minority use are frequently from nationally representative data which fail to oversample ethnic minorities leading to challenges in extrapolating results [33]. A further assessment of ethnic-specific TCAM use through conducting more culturally sensitive research may prove beneficial in helping healthcare providers and researchers to examine TCAM modalities that are prioritized by a particular group and thereby helping inform and develop potentially more targeted policies and services in this area.

Previous literature has found that cultural values, beliefs and practices are aspects of ethnicity that usually influence TCAM use [38, 43]. An inability of ethnic minorities to access healthcare also increases the likelihood of TCAM use [44], this is further exacerbated by other factors contributing to ethnic/racial disparities in healthcare including limited health insurance coverage and income levels [37, 40]. Our review identified a high rate of non-disclosure of TCAM use amongst ethnic minorities to conventional medical doctors which was comparable to reports from previous studies showing that a significant proportion of TCAM users (beyond ethnic minority populations) are reluctant to disclose usage to their conventional medical doctors [45,46,47,48]. Although previous literature did not specifically target ethnic minority TCAM users, the potential reasons for TCAM non-disclosure found in the general population appear consistent with our findings regarding ethnic minority patients including concerns around physician disapproval, discouragement, negativity and a lack of TCAM questioning by the doctor during consultation [45, 49]. Although inconclusive, this significant finding with regards to discrimination in some conventional health care settings, may in part help explain the increased likelihood of TCAM use and reports of non-disclosure amongst ethnic minority populations [44]. A better understanding of the reasons affecting ethnic minority patients’ (non) disclosure of their TCAM use [48] may well help inform improved communication between conventional medical doctors and their patients from ethnic minority communities (whether using or not using TCAM) and the provision of optimal services for those communities. Future research is warranted to explore reasons for non-disclosure and discriminatory experiences of medically underserved ethnic minorities in conventional health care settings.

Similar to other studies investigating ethnic minorities and TCAM users, our review found that having a positive perception about the efficacy of TCAM use increased the adoption and acceptance of TCAM approaches [33, 50]. Most ethnic minority participants reported in the reviewed literature had a high satisfaction with the effectiveness of TCAM. It is interesting that TCAM was considered harmless by most ethnic minorities in the reviewed literature and in some studies participants were unperturbed about the lack of positive outcomes as they were satisfied with knowing that there would be no harm to their wellbeing from using TCAM (33). Despite the general acceptance towards the use of TCAM as found in this review, the efficacy of different TCAM modalities still remains questioned with a number of studies labelling TCAM as an unproven therapy with unsubstantiated effectiveness [51, 52]. Some TCAM modalities have begun to attract emerging research evidence (albeit often only preliminary) with some positive results for acupuncture (for short/long term pain relief) [53, 54], relaxation techniques (for management of panic disorders, anxiety and insomnia) [55] and some herbal remedies (musculoskeletal conditions and other chronic conditions) [56, 57], although efficacy varies across TCAM modalities. Another potential benefit of TCAM may be its relative cost-effectiveness, with some studies in the US and Canada reporting that certain TCAM modalities used for selected conditions may provide savings for the wider healthcare system [55, 56]. Despite the still controversial location and role of TCAM in wider health care systems, prevalence rates in both ethnic and non-ethnic minority populations appear to be on the rise [56]. Further evaluation into the perceived effectiveness of TCAM in combination with or comparison to conventional medicine for the management and treatment of diverse health conditions is direly needed to better inform health service delivery to ethnic minority populations. Research is warranted to investigate the motivations and significance of concurrent use of TCAM and conventional medicine and non-disclosure of TCAM use to conventional medical doctors. There is a need for service providers and policy makers to acknowledge the substantial use of TCAM in their efforts to help develop effectiveness, safety and coordination of care for ethnic minority patients and populations.

This review is not without its limitations. Inclusion was restricted to only studies published in the English language, considering the target group (ethnic minorities) in review, there may be other research conducted and published in other languages that are relevant to this review but were excluded. Also, the review scope was limited to 2006–2017, thereby excluding some earlier research in this field. However, this time limit was chosen in order to encapsulate and identify the most recent and relevant research of pertinence to contemporary health care and health systems. Despite these limitations, this remains the first systematic review on this topic providing important insights for those providing and managing health care services for ethnic minority populations.

Conclusion

There appears to be substantial TCAM use amongst ethnic minority communities. While much of this use is concurrent to conventional health care there is often a lack of disclosure about TCAM use by ethnic minoritypatients to their conventional medical doctor(s). It is imperative that those developing health care services for ethnic minority populations are mindful of all the health-seeking choices and behaviours undertaken in these communities with a view to helping facilitate safe, effective and coordinated care for such patients.

References

Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics Hyattsville: Hyattsville; 2008.

Woerdenbag HJE, Jamu KO. Indonesian traditional herbal medicine towards rational phytopharmacological use. J Herb Med. 2014;4(2):51–73.

Robinson N, Blair M, Lorenc A, Gully N, Fox P, Mitchell K. Complementary medicine use in multi-ethnic paediatric outpatients. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008;14(1):17–24.

Broom A, Wijewardena K, Sibbritt D, Adams J, Nayar KR. The use of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine in Sri Lankan cancer care: results from a survey of 500 cancer patients. Public Health. 2010;124(4):232–7.

Assion HJ, Zarouchas I, Multamaki S, Zolotova J, Schroder SG. Patients’ use of alternative methods parallel to psychiatric therapy: does the migrational background matter? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116(3):220–5.

Hwang JH, Han DW, Yoo EK, Kim W-Y. The utilisation of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among ethnic minorities in South Korea. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:103-.

Shelley BM, Sussman AL, Williams RL, Segal AR, Crabtree BF.’They don’t ask me so I don’t tell them’: patient-clinician communication about traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine. Ann Family Med. 2009;7(2):139–47.

Roth MA, Kobayashi KM. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among Chinese Canadians: results from a national survey. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10(6):517–28.

Elewonibi BR, BeLue R. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine in immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18(3):600–7.

Tanaka MJ, Gryzlak BM, Zimmerman MB, Nisly NL, Wallace RB. Patterns of natural herb use by Asian and Pacific Islanders. Ethn Health. 2008;13(2):93–108.

Avogo W, Frimpong JA, Rivers PA, Kim SS. The effects of health status on the utilization of complementary and alternative medicine. Health Educ J. 2008;67(4):258–75.

Szczepura A. Access to health care for ethnic minority populations. Postgraduate medical journal. 2005;81(953):141–7.

Mackenzie ER, Taylor L, Bloom BS, Hufford DJ, Johnson JC. Ethnic minority use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): a national probability survey of CAM utilizers. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9(4):50.

Wardle J, Lui CW, Adams J. Complementary and alternative medicine in rural communities: current research and future directions. J Rural Health. 2012;28(1):101–12.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Higginbotham N, Albrecht G, Connor L. Health social science: a transdisciplinary and complexity perspective| NOVA. The University of Newcastle’s Digital Repository. 2001.

Law M, Steinwender S, Leclair L. Occupation, health and well-being. Can J Occup Ther. 1998;65(2):81–91.

Wells C, Kolt GS, Marshall P, Hill B, Bialocerkowski A. The effectiveness of pilates exercise in people with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. PloS ONE. 2014;9(7):e100402.

George M, Birck K, Hufford DJ, Jemmott LS, Weaver TE. Beliefs about asthma and complementary and alternative medicine in low-income inner-city African-American adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(12):1317–24.

Rao D. Choice of medicine and hierarchy of resort to different health alternatives among Asian Indian migrants in a metropolitan city in the USA. Ethn Health. 2006;11(2):153–67.

González-Vázquez T, Pelcastre-Villafuerte BE, Taboada A. Surviving the distance: the transnational utilization of traditional medicine among Oaxacan migrants in the US. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18(5):1190–8.

Yearwood EL. Child health care decision making and experiences of Caribbean women. J Pediatr Health Care. 2007;21(2):89–98.

Thomas F, Aggleton P, Anderson J. ‘Experts’, ‘partners’ and ‘fools’: exploring agency in HIV treatment seeking among African migrants in London. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(5):736–43.

Thorburn S, Faith J, Keon KL, Tippens KM. Discrimination in health care and CAM use in a representative sample of US adults. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19(6):577–81.

Meghani SH, Cho E. Self-reported pain and utilization of pain treatment between minorities and nonminorities in the United States. Public Health Nurs. 2009;26(4):307–16.

Arcury TA, Suerken CK, Grzywacz JG, Bell RA, Lang W, Quandt SA. Complementary and alternative medicine use among older adults: ethnic variation. Ethn Dis. 2006;16.

Gardiner P, Sadikova E, Filippelli AC, Mitchell S, White LF, Saper R, et al. Stress management and relaxation techniques use among underserved inpatients in an inner city hospital. Complement Ther Med. 2015;23(3):405–12.

Othman CN, Farooqui M. Traditional and complementary medicine. Proc Soc Behav Sci. 2015;170:262–71.

Arcury TA, Sandberg JC, Mora DC, Talton JW, Quandt SA. North Carolina Latino farmworkers’ use of traditional healers: a pilot study. J Agromed. 2016;21(3):253–8.

Harrison JK, Reid J, Quinn TJ, Shenkin SD. Using quality assessment tools to critically appraise ageing research: a guide for clinicians. Age Ageing. 2017;46(3):359–65.

Demark-Wahnefried W, Bowen DJ, Jabson JM, Paskett ED. Scientific bias arising from sampling, selective recruitment, and attrition: the case for improved reporting. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomark. 2011;20(3):415–8.

Fleming ML, Parker E. Introduction to public health. Australia: Elsevier; 2014.

Hwang JH, Han DW, Yoo EK, Kim W-Y. The utilisation of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among ethnic minorities in South Korea. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14(1):1–9.

Reid R, Steel A, Wardle J, Trubody A, Adams J. Complementary medicine use by the Australian population: a critical mixed studies systematic review of utilisation, perceptions and factors associated with use. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16(1):176.

Bishop FL, Lewith G. Who uses CAM? A narrative review of demographic characteristics and health factors associated with CAM use. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2010;7(1):11–28.

Laiyemo MA, Nunlee-Bland G, Adams RG, Laiyemo AO, Lombardo FA. Characteristics and health perceptions of complementary and alternative medicine users in the United States. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349(2):140–4.

Chao MT, Wade CM. Socioeconomic factors and women’s use of complementary and alternative medicine in four racial/ethnic groups. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(1):65.

Hsiao A-F, Wong MD, Goldstein MS, Yu H-J, Andersen RM, Brown ER, et al. Variation in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use across racial/ethnic groups and the development of ethnic-specific measures of CAM use. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12(3):281–90.

Upchurch DM, Rainisch BKW. Racial and ethnic profiles of complementary and alternative medicine use among young adults in the United States findings from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. J Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2012;17(3):172–9.

Rhee TG, Evans RL, McAlpine DD, Johnson PJ. Racial/ethnic differences in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in US adults with moderate mental distress results from the 2012 national health interview survey. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;8:43.

Bishop FL, Lewith GT. Who Uses CAM? A narrative review of demographic characteristics and health factors associated with CAM use. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med: eCAM. 2010;7(1):11–28.

Upchurch DM, Wexler Rainisch BK. Racial and ethnic profiles of complementary and alternative medicine use among young adults in the United States: findings from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. J Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2012;17(3):172–9.

Cui Y, Hargreaves MK, Shu X-O, Liu J, Kenerson DM, Signorello LB, et al. Prevalence and correlates of complementary and alternative medicine services use in low-income African Americans and whites: a report from the Southern Community Cohort Study. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18(9):844–9.

Ho DV, Nguyen J, Liu MA, Nguyen AL, Kilgore DB. Use of and interests in complementary and alternative medicine by Hispanic patients of a community health center. J Am Board Family Med. 2015;28(2):175–83.

Abou-Rizk J, Alameddine M, Naja F. Prevalence and characteristics of CAM use among people living with HIV and AIDS in Lebanon: implications for patient care. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2016;2016:5013132.

Thomson P, Jones J, Evans JM, Leslie SL. Factors influencing the use of complementary and alternative medicine and whether patients inform their primary care physician. Complement Ther Med. 2012;20(1–2):45–53.

Chang HY, Wallis M, Tiralongo E. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among people with type 2 diabetes in Taiwan: a cross-sectional survey. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:983792.

Chang H-Y, Chang H-L, Siren B. Exploring the decision to disclose the use of natural products among outpatients: a mixed-method study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:319.

Jou J, Johnson PJ. Nondisclosure of complementary and alternative medicine use to primary care physicians: findings from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):545–6.

Hsiao A-F, Wong MD, Goldstein MS, Yu H-J, Andersen RM, Brown ER, et al. Variation in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use across racial/ethnic groups and the development of ethnic-specific measures of CAM use. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12:281.

Tan G, Craine MH, Bair MJ, Garcia MK. Efficacy of selected complementary and alternative medicine interventions for chronic pain. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44(2):195.

Bardia A, Barton DL, Prokop LJ, Bauer BA, Moynihan TJ. Efficacy of complementary and alternative medicine therapies in relieving cancer pain: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(34):5457–64.

Rubinstein SM, van Middelkoop M, Kuijpers T, Ostelo R, Verhagen AP, de Boer MR, et al. A systematic review on the effectiveness of complementary and alternative medicine for chronic non-specific low-back pain. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(8):1213–28.

Haake M, Muller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, Basler HD, Schafer H, Maier C, et al. German acupuncture trials (GERAC) for chronic low back pain: randomized, multicenter, blinded, parallel-group trial with 3 groups. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(17):1892–8.

Kutch M. Cost-effectiveness analysis of complementary and alternative medicine in treating anxiety disorders. Altern Integr Med. 2016;5(218):2.

Ramsay C. Unnatural regulation: complementary and alternative medicine policy in Canada. Vancouver: The Fraser Institute; 2009.

Barner JC, Bohman TM, Brown CM, Richards KM. Use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for treatment among African-Americans: a multivariate analysis. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2010;6(3):196–208.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Australian Research Council (ARC) for supporting this research, Dr Josephine Agu and Distinguished Professor Adams via an ARC Professional Future Fellowship (FT140100195).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Agu, J.C., Hee-Jeon, Y., Steel, A. et al. A Systematic Review of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Amongst Ethnic Minority Populations: A Focus Upon Prevalence, Drivers, Integrative Use, Health Outcomes, Referrals and Use of Information Sources. J Immigrant Minority Health 21, 1137–1156 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-0832-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-0832-4