Abstract

We present a numerical procedure for elastic and nonlinear analysis (including fracture situations) of solid materials and structures using the discrete element method. It can be applied to strongly cohesive frictional materials such as concrete and rocks. The method consists on defining nonlocal constitutive equations at the contact interfaces between discrete particles using the information provided by the stress tensor over the neighbor particles. The method can be used with different yield surfaces, and in the paper, it is applied to the analysis of fracture of concrete samples. Good comparison with experimental results is obtained.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The discrete element method (DEM) has proven to be a very useful numerical tool for the computation of granular flows [1,2,3] (the hereafter termed noncohesive DEM) with or without coupling with fluids [4, 5] or structures [6]. These computations can include cohesive forces between particles [7] to model moisture, glue or other added features to the standard noncohesive DEM. Other research lines have focused on the DEM as a method to compute the mechanics of strongly cohesive materials, like rocks, concrete or cement [8,9,10]. The approach in these cases is usually termed as ‘bonded’ or ‘cohesive’ DEM. Here, the DEM can be understood as a discretization method for the continuum. The bonded DEM has also been combined with the finite element method (FEM) in order to save computation time [11].

The ability of the DEM to reproduce multicracking phenomena in cohesive materials is probably one of the main reasons why the DEM is chosen when fracture mechanics is an important ingredient of the solution. However, a deep analysis of the works published usually reveals a lack of accuracy of the DEM results in the elastic regime, together with the need for calibrating the DEM parameters for each application. It is quite surprising that the Poisson’s ratio and the shear modulus are seldom validated. It is, however, commonly accepted [12] that the Poisson’s ratio has a strong dependency on the mesh arrangement and the \(k_{t}/k_{n}\) ratio [13], where \(k_{n}\) and \(k_{t}\) are the normal and tangential spring stiffnesses, respectively, in the spring dashpot model that yields the forces at the contact interface between two spheres.

The difficulty of the bonded DEM to get accurate results when trying to capture simultaneously the Young’s modulus (E), the Poisson’s ratio (\(\nu \)) and the related shear modulus (G) derives from the fact that the bonded DEM works as a system of trusses instead of a true continuum. Usually, a good calibration of the microparameters (\(k_{n}\) and \(k_{t}\)) leads to a decent capture of one or two of the elastic macroparameters (E, \(\nu \) and G) for a given mesh arrangement and usually for a certain, limited, range of values [13]. Due to these limitations, the spring dashpot model has proven not to be good enough to capture the elastic behavior of a continuum with the DEM.

In a recent paper [14], we proposed a way to enrich the spring dashpot model in such a way that the elastic properties of a continuum can be accurately captured with the DEM. The improved bonded DEM approach is based on the definition of a nonlocal constitutive model at each contact interface in which the force–displacement relationship at an interface of a spherical particle depends on the forces at all the interfaces shared by the particle. The good properties of the new nonlocal bonded DEM procedure for predicting the elastic behavior of elastic continua modeled as a collection of regular and irregular distributions of spherical particles were shown. Indeed, the nonlocal bonded DEM procedure can be extended for modeling breakage and separation of particles in order to reproduce the nonlinear behavior of a continuum, leading to fracture and failure. In this work, we propose a new criterion for breaking the bonds between spherical particles based on the stress tensor at the contact interface. The stress tensor is very commonly used to trigger cracks in continuum mechanics, like in analytic solutions or in the FEM, but has not yet been used in DEM.

The arrangement of the paper is as follows. The nonlocal constitutive equations between forces and displacements at a contact interface are presented first. Also we describe how the stress tensor at the contact interface can be computed. The method for predicting the onset of fracture at a contact interface is then described. The last section of the paper presents the application of the new nonlocal bonded DEM technique to the analysis of uniaxial compression strength (UCS), a Brazilian tensile strength (BTS) test and a shear tests in concrete samples. Numerical results are compared with experimental data for the same tests with good agreement.

2 The stress tensor over discrete elements

The stress tensor, understood here as the Cauchy stress tensor, has been widely used in the context of the DEM. It is typically used to plot the value of the stresses in certain regions of the domain when dealing with granular materials [15]. For example, it is common to model soils with the DEM and to plot the stresses within the soil as a valuable engineering result.

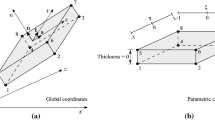

The averaged stress tensor over the volume of a central spherical particle, (hereafter termed particle 0) (Fig. 1), can be calculated as

In Eq. (1), index 0 denotes the central particle where stresses are computed, \(V_0\) is the volume of the spherical particle, \(n_{c}\) is the number of contacts of the particles with its neighbors, \(\varvec{l}_{i}\) is the vector connecting the center of the sphere to the ith contact point and \(\varvec{F_{i}}\) is the force vector at the ith contact point. The contact points can account for a certain gap between adjacent particles, as explained in [8].

Apart from granular noncohesive materials, the DEM has been used to model strongly cohesive materials like concrete or rocks [8] by means of the standard bonded DEM, which can withstand tractions at a contact interface. The packing of spheres is expected to work as an equivalent continuum, and the stress tensor at the center of each particle can be calculated with Eq. (1) as well.

The idea of using the stress tensor at a particle to enrich the information used to compute the forces between bonded particles emulating a continuum was first presented Celigueta et al. [14]. The normal force at a contact point is computed in terms of the nodal overlap and the stresses at the contact point as

where \(F_{z'_{i}}\) is the force between the two particles in the normal direction \(z'\) (defined by the vector that joins the particle centers as shown in Fig. 2), \(A_{i}\) is the contact area at the ith contact interface between the two particles (particle 0 and particle I, see Fig. 1), \(\delta _{z'i}\) is the overlap between the particles, \(\nu \) is the Poisson’s ratio and \(k_{ni}\) is a normal stiffness parameter associated with each pair of particles given by

where \(L_{0i}\) is the distance between the centers of the particles at the stress-free position and E is the Young’s modulus of the continuum material [14].

In Eq. (2), \(\sigma _{x'i}\) and \(\sigma _{y'i}\) are the axial stresses at the contact point in the two orthogonal directions to the normal one. They can be obtained by rotating the coordinate system for the stress tensor at the ith contact point, \(\varvec{\sigma }_{i}\), as follows (Eq. (4)):

where \(\varvec{R}_{i}\) is the rotation matrix between the Cartesian and the local axes of contact i and \(\varvec{\sigma }'_{i}\) is the stress tensor expressed in the local coordinate system at that contact [14].

The stress tensor at the ith contact point is computed by averaging the values of the stress tensors of the contacting spheres sharing the ith contact part (sphere 0 and sphere I) via Eq. (5). This gives

Note that Eq. (2) is a nonlocal constitutive expression that relates the normal force to the values of the stress at the particles adjacent to the central sphere.

The tangential forces at the ith contact point are similarly computed in a nonlocal form as

where \(\tau _{z'x',i}\) and \(\tau _{z'y',i}\) are the tangential components of the local stress tensor at the ith contact point, \(\varvec{\sigma }'_{i}\) (Eq. (4)). Subindex step in Eq. (6) denotes the time step at which the different terms are approximated. For explicit dynamic solution schemes, step refers to the previous time step. For implicit schemes, step refers to the current time step and the term is updated iteratively. Note that both \(\tau _{z'x',i}\) and \(\tau _{z'y',i}\) depend on the stress tensor for each particle (computed by Eq. (1)). Therefore, their value has to be used from either the previous time step or the previous iteration. Otherwise, the forces would never be updated according to the relative displacements. The subindex step in Eq. (6) avoids the substitution of \(A_{i}G\left( \frac{\delta _{x'i}}{L_{i}}\right) _\mathrm{step}\) by \(k_{ti}\delta _{x'i}\), which would cancel terms and make the expression independent from the relative displacements between the particles.

We highlight that both the normal and tangential forces make use of the averaged stress tensor \(\varvec{\sigma }_{i}\) at each contact point. This increases the stencil of neighboring spheres considered for computing the forces at each contact point.

Details of the computation of the stress tensor at each particle from the normal and tangential forces, the computation of the contact areas, the necessary adjustment of the porosity of the packing and the correction of the volume and mass of the particles can be found in [14].

In [14], several other adjustments are proposed aiming at avoiding calibration of the contact parameters. However, those suggestions fall out of the scope of this work, the purpose of which is to extend the applicability of nonlocal bonded DEM to the postelastic regime.

3 Using the stress tensor to compute the crack initiation

Yield surfaces in continuum mechanics are designed to model the behavior of a specific group of materials. For example, the Rankine yield surface [16] is intended for concrete or other materials whose failure is mainly tension-driven, as these materials present a much higher strength in compression than in tension. As a different example, the von Mises yield surface is typically used for metals, giving importance to the deviatoric stresses as initiators of the nonlinearity.

Even if these yield surfaces are used to trigger a brittle fracture, this does not mean that the macroscopic response of the sample subject to stresses presents a brittle behavior. Actually, the postelastic behavior depends on the shape of the sample and the load type. Thus, for the same material properties, we can see a totally brittle response in a bending test and a smoother nonlinear graph in a UCS test.

The traditional way to detect the initiation of postelastic behavior in a continuum is the verification of a certain yield condition expressed in terms of the stress tensor written as \(f (\sigma _{ij})\ge 0\) [17].

The novel idea presented in this paper is to use the stress tensor at a bond (computed by Eq. (5)) and a yield surface to trigger a crack at the contact interface between two spheres in the bonded DEM.

The way to assess whether a stress tensor verifies or not the yield conditions changes with each specific constitutive model. Some examples are given in Sects. 5 and 6 of this work using Rankine and Mohr–Coulomb yield surfaces. Indeed, many other examples can be found in the literature of plasticity, damage and fracture mechanics.

The proposed crack initiation criterion is independent from the specific orientation of the bond, as the stress tensor represents all the orientations in a single matrix.

With this methodology, the concept of using the stress tensor for the elastic regime presented in [14] is extended to the postelastic branch, as a criterion for breaking the bond.

The next section shows the behavior of concrete samples discretized by means of the bonded DEM subject to loads, whose bond breakage is ruled by the Rankine and Mohr–Coulomb yield surfaces [18].

The chosen yield surfaces have been introduced in DEMpack code developed by the authors [19] and tested with several samples under different loads. The code has been implemented within the open-source Kratos Multiphysics framework [20]. The data preparation and visualization of results in this paper were carried out with the GiD pre- and postprocessor software [21].

4 Description of the experimental tests

Three different experimental tests on several concrete samples were carried out at the laboratory of the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC) [22]. All samples were subject to an increasing load until failure. The limit stress at which the samples analyzed for each test broke was measured and averaged. The material tested was identified as a 50 MPa concrete, with a measured Young’s modulus (E) of 40 GPa (coefficient of variation of 2.5%). The Poisson’s ratio was not measured. The same tests were modeled with the nonlocal bonded DEM using the Rankine and Mohr–Coulomb yield surfaces, and the DEM results were compared with the experimental values. Young’s modulus of \(E=40\) GPa and a Poisson’s ratio value of \(\nu =0.2\) were used in all the nonlocal DEM computations. The three tests are described next.

4.1 Test 1: uniaxial compressive strength (UCS)

A concrete cylindrical specimen of 100 mm diameter and 200 mm length was loaded in uniaxial compression along its symmetry axis (Fig. 3).

UCS test scheme [23]

Figure 4 shows a number of broken specimens after the tests.

The average limit stress reached by the sample was 55 MPa.

For the numerical computation with the nonlocal bonded DEM, a random packing of 12,000 spheres was used to model the cylinder. Two plates compressed the sample at a relative velocity of 0.05 m/s, and the force on the upper plate was measured, divided by the cross section of the sample and plotted as stress vs. strain of the sample. The loading velocity used in the computation does not correspond to the loading velocity of the experiments. It was chosen as fast as possible, making sure that no elastic waves were generated. The coefficient of restitution was set to 0.0 in all runs for all tests.

4.2 Test 2: Brazilian tensile strength (BTS) test

A cylindrical specimen of 100 mm diameter and 200 mm length was loaded in a biaxial stress state, generated by a diametral compression that generates a perpendicular, diametral traction (Fig. 5).

BTS test scheme [24]

Figure 6 shows a number of broken specimens after the tests.

The average limit stress reached by the sample was 4 MPa.

For the numerical computation with the DEM, a random packing of 9,000 spheres was used to model the cylinder. Two plates compressed the sample and the force on the upper plate was used to evaluate the stress at the center of the sample (Eq. (7)) as it was done for the experimental tests. The stress was plotted vs. the elapsed time. The relative velocity of the plates was 0.1 m/s. Again, this does not necessarily correspond to the experimental loading velocity.

In Eq. (7), f is the measured force, R is the radius of the sample and L is the length of the sample (thickness of the slice).

4.3 Test 3: shear strength test

Cylindrical specimens of 150 mm diameter and 80 mm height were used. The samples had two parallel flat ends and two inversed tubular coaxial borings set at a diameter of 45 mm and a width of 4 mm. The depth of the borings was 10 mm, leaving an effective shear section height of 60 mm (see Fig. 7 for clarification).

The inner cylinder was pushed downward by a piston while the outer cylinder was supported by a holed plate.

Figure 8 shows a number of broken specimens after the tests.

It can be observed that several types of cracks were created, some around the inner cylinder of circumferential type, some in the outer part of radial type.

For the numerical computation with the DEM, a random packing of 161,000 spheres was used to model the cylinder. The upper plate, pushing the inner part of the sample, moved downward at a constant velocity of 0.1 m/s. The force on the upper plate was measured and plotted vs. the elapsed time.

5 DEM results with the Rankine yield surface

5.1 Yield surface definition

The Rankine yield surface is defined as

where \({\sigma }_{1}\) is the maximum principal stress and \({\sigma }_{R}\) is a limit value, which can be obtained experimentally as the pure tension limit stress. We assume \({\sigma }_{1}\ge {\sigma }_{2}\ge {\sigma }_{3}\), where \({\sigma }_{2}\) and \({\sigma }_{3}\) are the second and third principal stresses, respectively. Tractions are taken as positive. The behavior of the material is considered elastic as long as \({\sigma }_{1}\le {\sigma }_{R}\). If \({\sigma }_{1}\ge {\sigma }_{R}\) at any bond, the bond breaks. Figure 9 depicts the Rankine yield surface in the space of principal stresses.

5.2 Calibration of parameters

For the Rankine yield surface, two important parameters need to be calibrated: the maximum value for a principal stress, \({\sigma }_{R}\), and Coulomb’s frictions parameter, \(\mu \). The procedure followed to calibrate those values was the following:

- 1.

Step 1 Run Test 1 (UCS) iteratively changing the value of \({\sigma }_{R}\), but keeping fixed the value of \(\mu \) (first computations can be run with \(\mu =0.2\)). Coulomb’s friction has little effect on the limit stress that the sample can withstand.

- 2.

Step 2 Run Test 2 (BTS) to check that the value of \({\sigma }_{R}\) yields good results and adjust the value slightly to match the experimental value.

- 3.

Step 3 Run Test 3 (Shear) iteratively changing the value of \(\mu \), but keeping fixed the value of \({\sigma }_{R}\) obtained after Steps 1 and 2. Once the best possible value for \(\mu \) is found, go to Step 1 and start the process again.

It was found that following these steps twice was enough to find a set of parameters which were useful to work with a given material.

5.3 Computational results

For all the computations, the input value of the Young’s modulus was 40 MPa, and the Poisson’s ratio was taken as 0.20.

After the calibration process, the limit tensile stress for the nonlocal DEM computations was chosen as \(\sigma _{R}= 6\) MPa and the friction coefficient was chosen as \(\mu =0.1\), both between spheres and between spheres and walls. These material parameters were used for the DEM analysis of the three tests described in Sect. 4.

The packing of spheres used for Test 1 (UCS) contained 12K spheres, and their size is detailed in the graph in Fig. 10. The results of the stress–strain graph for Test 1 (UCS) are shown in Fig. 11. In all cases, the horizontal lines mark the upper and lower values of the limit stress obtained experimentally. The Young’s modulus which can be observed in the graph is 38 MPa, close to the input parameter (40 MPa). Note that no calibration was needed to obtain this similarity in the elastic property, as proven in [14]. Good agreement with the limit stress computed with the DEM is obtained. The broken sample is shown in Fig. 12.

The packing of spheres used for Test 2 (BTS test) contained 9K spheres, and their size is detailed in the graph in Fig. 13. The results of the stress–time graph for Test 2 are shown in Fig. 14. Good agreement with the experimental results is again obtained. The broken sample is shown in Fig. 15.

The packing of spheres used for Test 3 (Shear test) contained 161K spheres, and their size is detailed in the graph in Fig. 16. The notches present in this geometry required spheres much smaller than in the other tests. The results of the force–time graph for Test 3 are shown in Fig. 17. The limit force obtained differs in 10% with the lower value of the experimental result. The broken sample is shown in Fig. 18.

6 Mohr–Coulomb yield surface

6.1 Yield surface definition

The Mohr–Coulomb yield surface is defined as

where \({\sigma }_{1}\) is the maximum principal stress, \({\sigma }_{3}\) is the minimum principal stress, c is the Mohr–Coulomb ’cohesion’ stress parameter and \(\phi \) is the Mohr–Coulomb internal friction parameter.

6.2 Calibration of parameters

For the Rankine yield surface, three important parameters need to be calibrated: Mohr–Coulomb strength parameters, c and \(\phi \) , and Coulomb’s frictions parameter, \(\mu \). The procedure followed to calibrate those values was the following:

- 1.

Step 1 Run Test 1 (UCS) iteratively changing the value of c and \(\phi \), but keeping fixed the value of \(\mu \) (first computations can be run with \(\mu =0.2\)). Coulomb’s friction has little effect on the limit stress that the sample can withstand.

- 2.

Step 2 Run Test 2 (BTS) to check that the value of c and \(\phi \) yields good results and adjust the value slightly to match the experimental value. Both parameters must be adjusted by the user according to the sensitivity observed.

- 3.

Step 3 Run Test 3 (Shear) iteratively changing the value of \(\mu \), but keeping fixed the value of c and \(\phi \) obtained after Steps 1 and 2. Once the best possible value for \(\mu \) is found, go to Step 1 and start the process again.

It was found that following these steps twice was enough to find a set of parameters which were useful to work with a given material.

6.3 Computational results

The same packings of spheres used for the Rankine yield surface were used for the Mohr–Coulomb yield surface.

The values of c and \(\phi \) for all the numerical computations were calibrated to 14.5 MPa and 60 degrees, respectively. A friction coefficient of \(\mu = 0.1\) was chosen as for the computations using the Rankine yield surface (Sect. 5.3). Here, the calibration of the two material parameters c and \(\phi \) was more difficult than the calibration of \({\sigma }_{R}\).

The results of the stress–strain graph for Test 1 (UCS), Test 2(BTS) and Test 3 (Shear Test) are depicted in Figs. 19, 21 and 23, respectively. The broken samples for each case are shown in Figs. 20, 22 and 24.

Good agreement between the experimental values and the nonlocal bonded DEM results for the limit stress (UCS and BTS tests) and the limit force (Shear strength test) was obtained in all cases.

7 Conclusions

The nonlocal bonded DEM presented in this work can be effectively used to model the elastic range and the nonlinear material behavior, at least until the solid starts collapsing, for a family of materials similar to the tested ones (concrete samples). The behavior of the material after the collapse of the sample is left for subsequent publications. The presented approach is capable of accurately predicting the onset and initial evolution of cracks. After that, the DEM is capable of computing the displacements and rotations of any part of the solid which might get detached due to the evolution of the cracks.

The numerical examples presented in the paper have shown that the nonlinear and failure behavior of concrete samples in standard laboratory tests can be accurately predicted with the nonlocal bonded DEM using the Rankine or the Mohr–Coulomb yield surfaces. The capabilities of the nonlocal bonded DEM, however, extend beyond the yield functions chosen in this work. Any yield surface modeling material failure that can be fed with the stress tensor can be used for nonlinear analysis of solids with the nonlocal bonded DEM. This makes the nonlocal bonded DEM a powerful numerical tool for nonlinear analysis of a broad range of materials and structures.

The average number of bonds of each sphere (coordination number) or the size of the particles used in the computations might affect significantly the behavior of the solid once the crack is initiated or well developed; however, this will be studied in further publications.

References

Cundall PA, Strack OD (1979) A discrete numerical model for granular assemblies. Geotechnique 29(1):47–65

Langston PA, Tüzün U, Heyes DM (1995) Discrete element simulation of granular flow in 2D and 3D hoppers: dependence of discharge rate and wall stress on particle interactions. Chem Eng Sci 50(6):967–987

Cleary PW, Sawley ML (2002) DEM modelling of industrial granular flows: 3D case studies and the effect of particle shape on hopper discharge. Appl Math Model 26(2):89–111

Xu BH, Yu AB (1997) Numerical simulation of the gas-solid flow in a fluidized bed by combining discrete particle method with computational fluid dynamics. Chem Eng Sci 52(16):2785–2809

Tsuji Y, Kawaguchi T, Tanaka T (1993) Discrete particle simulation of two-dimensional fluidized bed. Powder Technol 77(1):79–87

Oñate E, Labra C, Zárate F, Rojek J (2012) Modelling and simulation of the effect of blast loading on structures using an adaptive blending of discrete and finite element methods. In: Escuder-Bueno et al (eds) Risk analysis, dam safety, dam security and critical infrastructure management, vol 53. Taylor & Francis Group, London, pp 365–372

Moreno R, Ghadiri M, Antony SJ (2003) Effect of the impact angle on the breakage of agglomerates: a numerical study using DEM. Powder Technol 130(1):132–137

Oñate E, Zárate F, Miquel J, Santasusana M, Celigueta MA, Arrufat F, Gandikota R, Valiullin KM, Ring L (2015) A local constitutive model for the discrete element method. Application to geomaterials and concrete. Comput Part Mech 2(2):139–160

Brown NJ, Chen JF, Ooi JY (2014) A bond model for DEM simulation of cementitious materials and deformable structures. Granul Matter 16(3):299–311

Rojek J, Oñate E, Labra C, Kargl H (2011) Discrete element simulation of rock cutting. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 48(6):996–1010

Oñate E, Rojek J (2004) Combination of discrete element and finite element methods for dynamic analysis of geomechanics problems. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 193(27):3087–3128

Hentz S, Daudeville L, Donzé FV (2004) Identification and validation of a discrete element model for concrete. J Eng Mech 130(6):709–719

Labra CA (2012) Advances in the development of the discrete element method for excavation processes. Ph.D. thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona

Celigueta MA, Latorre S, Arrufat F, Oñate E (2017) Accurate modelling of the elastic behavior of a continuum with the discrete element method. Comput Mech 60(6):997–1010

Rojek J, Karlis GF, Malinowski LJ, Beer G (2013) Setting up virgin stress conditions in discrete element models. Comput Geotech 48:228–248

Rankine WM (1856) On the stability of loose earth. Proc R Soc Lond 185–187

Belytschko T, Liu WK, Moran B, Elkhodary K (2013) Nonlinear finite elements for continua and structures. Wiley, New York

Labuz JF, Zang A (2012) Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion. Rock Mech Rock Eng 45(6):975–979

www.cimne.com/dempack. Accessed 20 Aug 2019

Dadvand P, Rossi R, Oñate E (2010) An object-oriented environment for developing finite element codes for multi-disciplinary applications. Arch Comput Methods Eng 17(3):253–297

Ribó R, Pasenau M, Escolano E, Ronda JS, González LF (1998) GiD reference manual. CIMNE, Barcelona

Informe de resultados (2015) Fabricación y caracterización de hormigones H30 y H50. Technical report of the international centre for numerical methods in engineering (CIMNE), IT644. Published in Scipedia

http://osp.mans.edu.eg/geotechnical/Ch1C.htm. Accessed 20 Aug 2019

ASTM Standard C496 (2002) Standard test method for splitting tensile strength of cylindrical concrete specimens. ASTM International, West Conshohocken

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Juan Miquel and Dr. Francisco Zárate for their suggestions during the development of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Celigueta, M.A., Latorre, S., Arrufat, F. et al. An accurate nonlocal bonded discrete element method for nonlinear analysis of solids: application to concrete fracture tests. Comp. Part. Mech. 7, 543–553 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40571-019-00278-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40571-019-00278-5