Abstract

Depression has long been a clinical concern in youth with autism, yet systematic research examining its prevalence, presentation, and treatment has only begun to emerge more recently. Using the search terms autism, asd, or autistic and depression, depressive, dysthymia, or dysthymic, this systematic review identified 43 articles focused on symptoms of depression in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders published between 2012 and 2016. The results of the review indicate that depression is more common in youth with autism spectrum disorders than in typically developing youth and is associated with a multitude of other medical and psychiatric conditions. Unfortunately, few intervention studies have been conducted despite evidence of need and preliminary efficacy for some psychosocial and pharmacological treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impairment in social communication and a pattern of restricted and repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Once thought to be rare, current prevalence estimates suggest that as many as 1 in every 59 children may be affected by ASD (Baio et al. 2018) across all racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups.

Children with ASD can present with a broad spectrum of symptoms. Additionally, children with ASD often exhibit comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions (Bauman 2010; Simonoff et al. 2008), a number of which share features with autism. In this context, it may be challenging to differentiate true comorbidity from overlapping symptomatology. Further complicating potential diagnosis, individuals with ASD often differ significantly in cognitive ability and adaptive functioning and may have difficulty in effectively communicating internal states.

One of the psychiatric disorders most commonly comorbid with ASD is depression (Leyfer et al. 2006). Marked by persistent and intense feelings of sadness, major depressive disorder (MDD; American Psychiatric Association 2013) often first appears in childhood or adolescence (Birmaher et al. 1996) and has significant detrimental effects on the physical, social, and academic functioning of young people (Jaycox et al. 2009).

Concerns around low and depressed mood in individuals with ASD have been reported for a number of years (Wing 1981), but the majority of research examining its prevalence, presentation, and treatment has been published in the last several years. The last systematic review of depression in autism, conducted by Stewart et al. (2006), included all ages and found only 27 studies. Stewart et al. (2006) performed an inclusive search of several online databases (i.e., MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science) from their inception and examined the reference sections of articles ascertained from this initial search for relevant studies; however, due to the limited number of studies and few participants in each study, Stewart et al. (2006) were only able to surmise that depression is indeed common in individuals with ASD and that it appears to be effectively treated with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. More recent literature reviews have not been systematic in nature (e.g., Magnuson and Constantino 2011), perhaps due to the vast quantity of research that has been published on this important topic in the last several years. The objective of this systematic review is to provide an update on previous reviews on the prevalence, presentation, and treatment of depression in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (e.g., Magnuson and Constantino 2011; Stewart et al. 2006), as well as offer guidance for possible directions for future research.

Methods

The research team utilized systematic methods to search for journal articles published from 2012 to 2016 regarding the prevalence, presentation, and treatment of depression in youth with ASD. This systematic review protocol followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses for Protocols (PRISMA-P; Moher et al. 2015).

Identification and Selection of Studies

MEDLINE Complete and PsycINFO online databases were concurrently searched for entries published between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2016, with abstracts containing any combination of the following terms: (1) autism, asd, or autistic and (2) depression, depressive, dysthymia, or dysthymic. The search was limited to peer-reviewed journal articles published in English. Articles were independently screened by two authors for the criteria of inclusion. After iterative discussion, agreement was reached as to whether the identified articles met the inclusion criteria (outlined below).

Studies identified from the initial search were evaluated for the following pre-determined inclusion criteria: (a) a peer-reviewed study published in English, (b) described original research, (c) participants were school-age children and/or adolescents (average age 6–17 years) diagnosed with ASD, (d) symptoms of depression in this population were directly measured through standardized assessment or report, and (e) depression was documented as an independent construct. Studies examining general internalizing symptoms or mixed anxiety/depression were excluded, as were studies examining depression in the presence of mania.

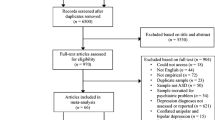

The initial search yielded 784 studies from MEDLINE Complete and 815 studies from PsycINFO. When duplicates were removed, 1334 articles were evaluated for eligibility. Of those 1334 articles, 43 met the inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1; Moher et al. 2009). Articles that met the inclusion criteria were subsequently divided into three broad categories according to their primary focus: prevalence, presentation, or treatment (see Tables 1, 2, and 3, respectively).

Data Extraction

Two authors extracted and coded data from the selected studies. After discussion, agreement was reached for the coding of variables of interest. Variables of interest included publication author(s) and year, sample size and demographics, methodological characteristics, result(s), and biases and limitations.

Results

Prevalence

Large-scale population-based studies have not been conducted on the incidence and prevalence of comorbid depression in young people with ASD. Of the studies that have been conducted, observed prevalence rates have varied significantly.

These discrepancies likely reflect differences in sample characteristics and/or method(s) of assessment. Although samples were predominantly composed of Caucasian males without intellectual disability (ID), several studies included a small subset of girls (e.g., Amr et al. 2012; Hammond and Hoffman 2014; Hebron and Humphrey 2012) and one study included participants with a range of intelligence quotients (IQs; Amr et al. 2012); furthermore, one investigation included a significant number of racial minority participants, and over 20% of the total sample was not Caucasian (Goldin et al. 2014). In terms of the method of assessment, most investigations relied on self-report or other reports of depression symptoms (e.g., Bitsika and Sharpley 2015; Hammond and Hoffman 2014; Hebron and Humphrey 2012; Mazzone et al. 2013). Several employed clinical interview (e.g., Amr et al. 2012; Caamaño et al. 2013). Although reported prevalence rates for MDD varied significantly, from 7% (Orinstein et al. 2015) to 47.1% (Bitsika and Sharpley 2015) of the ASD sample, youth with autism spectrum disorder exhibited elevated symptoms of depression compared to typically developing (TD) youth (e.g., Caamaño et al. 2013; Goldin et al. 2014) and atypically developing youth (e.g., Hebron and Humphrey 2012). These differences were consistent across methods of assessment, including self-report (e.g., Bitsika and Sharpley 2015; Hebron and Humphrey 2012), parent report (e.g., Gadow et al. 2012; Hammond and Hoffman 2014), teacher report (e.g., Gadow et al. 2012; Hammond and Hoffman 2014), and clinical interview (e.g., Caamaño et al. 2013; Orinstein et al. 2015), as well as across races (Goldin et al. 2014), levels of intelligence (Amr et al. 2012), and genders (e.g., Goldin et al. 2014; Hebron and Humphrey 2012).

The only study to examine the prevalence of depression in youth with ASD with a range of full-scale IQs (FSIQs; range = 20–105) was conducted by Amr et al. (2012) in three Arab countries. Thirty-seven boys and 23 girls (6–11 years old) with ASD were recruited from clinics in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan. ASD diagnosis was made by child psychiatrists in each country. The children were diverse in their country of origin, FSIQ, gender, family income, family size, and level of maternal and paternal education. According to best-estimated diagnoses, eight children (13.3%) met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria for MDD (4th ed., text rev., DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association 2000). Diagnoses were determined by clinical psychiatric interview and the Semi-Structured Clinical Interview for Children and Adolescents (McConaughy and Achenbach 1994). This study confirms the frequent co-occurrence of ASD and MDD and is consistent with studies from Western countries, which have reported high rates of comorbid depression in youth with autism (e.g., Bitsika and Sharpley 2015; Hebron and Humphrey 2012; Mazzone et al. 2013). This investigation also suggests the presence of depression across a range of FSIQs. Many studies have excluded participants with IQs below 70 in their examination of depression in ASD (e.g., Hammond and Hoffman 2014; Hebron and Humphrey 2012), but, in this study, approximately two thirds of the sample had ID and 28.3% (n = 17) had a history of epileptic seizures. Even in this lower functioning sample, over 13% of participants met the DSM-IV-TR criteria for MDD (American Psychiatric Association 2000), although it should be noted that it was not specified what percentage of those that met criteria for MDD were children with ID.

Strang et al. (2012) examined the prevalence of clinical depression symptoms in 95 children (aged 6–12 years, n = 54) and adolescents (aged 13–18 years, n = 41) with ASD without ID. The group’s mean FSIQ was in the average range (mean = 105), and those with a neurological or genetic disorder were excluded. All participants met criteria for a “broad ASD” according to criteria established by the Collaborative Programs for Excellence in Autism (Lainhart et al. 2006) on the Autism Diagnostic Interview (ADI; Le Couteur et al. 1989), Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Lord et al. 1994), or Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al. 2000). Depression symptoms were assessed with the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach and Rescorla 2001), a standardized parent report questionnaire of youth emotional and behavioral functioning, and compared to the CBCL standardization sample. It was found that 30% of the ASD sample was in the clinical range for depression symptoms on the CBCL.

Findings from a study conducted by Orinstein et al. (2015) suggest that depression symptoms are less prevalent in children that will lose their ASD diagnosis. Orinstein et al. (2015) compared past (i.e., lifetime) and present psychiatric symptoms in these so-called optimal outcome (OO) youth (n = 33), TD youth (n = 34), and youth with high-functioning autism (n = 42). To be included in the ASD group, participants had to meet the ADOS criteria for autism (Lord et al. 2000). To be included in the OO group, participants must have had an ASD diagnosis before age 5 documented by a physician or psychologist but, at the time of evaluation, must not have met the ADOS criteria for ASD (Lord et al. 2000). According to the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (Kaufman et al. 1997), which was administered to the parents of study participants, there was more past and present MDD in the ASD group than the OO or TD groups. Three individuals (7%) from the ASD group met criteria for a present MDD versus only one individual (3%) from the OO group and no individuals (0%) from the TD group; furthermore, eight individuals (19%) from the ASD group met criteria for MDD in their past versus only one individual (3%) from the OO and TD groups.

In their investigation into the level of depressive symptomatology in boys (7–17 years old) with ASD, Mazzone et al. (2013) compared the prevalence and severity of depression symptoms in the ASD group to those of age-matched samples of TD boys and boys diagnosed with major depression. Participants included in the ASD group had been diagnosed with ASD according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association 2000), and participants included in the major depression group had been diagnosed with MDD according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association 2000). Depression symptoms were assessed through self-report, with the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs 1982), and semi-structured interview, with the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R; Poznanski and Mokros 1996). CDI total symptoms scores reached a clinical cutoff in 8.4% (n = 8) of the ASD group, in 6.3% (n = 6) of the major depression group, and in 0% (n = 0) of the TD group. CDRS-R total symptoms scores reached a clinical cutoff in 26.3% (n = 25) of the ASD group, in 31.5% (n = 30) of the major depression group, and in 8.4% (n = 8) of the TD group. The ASD group reported significantly more severe depression symptoms than the TD group, as demonstrated by CDI and CDRS-R scores; however, comparison of depression symptom severity between the ASD and MDD groups yielded mixed results. The ASD and MDD groups were not significantly different in their CDI total scores but were significantly different in their CDRS-R total scores.

Comparing the self-reported mental health problems of adolescents with ASD (n = 22) with age-, gender-, and special educational needs-matched groups of adolescents with dyslexia (DYS; n = 21) and a group of TD adolescents (n = 23), Hebron and Humphrey (2012) found a clear trend toward more depression in youth with ASD. Participants (aged 11–17 years) were recruited from several mainstream secondary schools. In all three groups, teens with comorbid difficulties were excluded. Participants completed the Beck Youth Inventories Second Edition (Beck 2005). Compared with 8.7% of the TD group, 36.4% of the ASD group scored at or above the clinical cutoff for depression, with an associated odds ratio of 6. Additionally, the ASD group trended toward greater depression symptoms compared with the DYS group, although this trend was not significant. These results indicate that symptoms of depression are common in ASD community samples, as well as in clinical settings (e.g., Amr et al. 2012; Mazzone et al. 2013).

Bitsika and Sharpley (2015) also examined the prevalence and severity of depression symptoms in a community-based sample of youth with ASD. Seventy young males (aged 8 to 18 years) comprised the ASD group. Fifty age- and IQ-matched males comprised the TD group. All of the participants with ASD were recruited from local schools or parent support groups and had ASD diagnosis affirmed by a 2-h clinical interview. TD participants were recruited from the same general community. All participants had a FSIQ above 90, and none had a known history of a genetic, neurological, or psychiatric disorder. Depression symptoms were assessed via self-report with the Depression subscale of the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory (CASI-D; Gadow and Sprafkin 2002), which has been used with children and adolescents with ASD (Gadow et al. 2005). The CASI-D enables the designation of an individual as having MDD by the presence of at least five of the DSM-5 criteria (Gadow and Sprafkin 2010). When these criteria were applied, 33 young people (47.1%) from the ASD sample were classified as having MDD, whereas only 2 participants (3.9%) from the TD group were qualified for a MDD diagnosis. As a group, ASD participants had significantly higher CASI-D scores than TD youth, and ASD youth reported 50% higher scores than TD youth for 8 of the 10 CASI-D symptoms. In addition, Bitsika and Sharpley (2015) examined the depression symptom profiles in their sample of boys with ASD and found that anhedonia was the most powerful predictor of depression in this group. Notably, over 45% of a community-based ASD sample qualified for a comorbid diagnosis of MDD, although none had previously received the diagnosis. These findings should alert clinicians to the importance of assessing youth with autism for comorbid major depression.

Presentation

A multitude of studies have investigated the presentation and clinical correlates of depression in youth with ASD. Such investigations have examined its assessment and diagnosis, genetic underpinnings, and associations with demographic characteristics, other medical and psychiatric conditions, and the core symptoms of ASD.

Given the negative impact of comorbid depression on young people with autism, accurate assessment and timely diagnosis are crucial; however, assessing comorbidity in youth with ASD presents a number of challenges. ASD shares many features with other disorders, and it may be difficult to distinguish true comorbidity from overlapping symptoms; furthermore, the ability of those with autism spectrum disorder to self-report emotional states and negative thoughts has been a subject of considerable discussion (e.g., Ozsivadjian et al. 2014) given the well-established challenges these individuals have in accurate assessment of their social deficits (Lerner et al. 2012). Nonetheless, several studies have found satisfactory convergence in parent report and self-report by youth with ASD for symptoms of depression (e.g., Bitsika and Sharpley 2016b; Bitsika et al. 2016a; Sterling et al. 2015).

Ozsivadjian et al. (2014) found good agreement between young people with ASD and their parents on the CDI (Kovacs 1982). Thirty boys (11–15 years old) with ASD with IQs ≥ 70 completed the CDI, and their parents completed the parent version. Correlations indicated good agreement between parent and self-report on the CDI total score (p < 0.05). Additionally, the ASD sample completed the Children’s Automatic Thoughts Scale (CATS; Schniering and Rapee 2002), a self-report questionnaire designed to capture youth’s negative automatic cognitions. Analyses showed that CATS scores were positively related to self-reported CDI scores. The results of this study reveal that cognitively higher-functioning young people with ASD can accurately report their negative thoughts and that these thoughts reflect symptoms of depression. It appears that existing measures, such as the CDI, can be appropriate for the assessment of depressive symptomatology in a subset of youth with ASD; however, some children with autism have limited functional communication skills and would be unable to provide a self-report of emotional problems. As such, it is important to explore other potential methods of assessment.

There has been interest in the relationship between gene variants and ASD’s comorbidity with depression (Gadow et al. 2014a, b). Findings suggest that some serotonin gene (i.e., HTR2A) variants (Gadow et al. 2014b) and dopamine gene (i.e., DAT1 and DRD2) variants (Gadow et al. 2014a) may be associated with more severe symptoms of depression in children with ASD. It has been shown that ASD youth homozygous for the G allele of a single nucleotide polymorphism (rs6311) in HTR2A exhibited more severe parent-reported depression symptoms than those with the G/A or A/A genotypes (Gadow et al. 2014b). It has also been found that children with ASD homozygous for the six-repeat allele of DAT1 intron 8 exhibited more severe parent-reported symptoms of depression than 5/6 heterozygotes (Gadow et al. 2014a). Additionally, children homozygous for the G allele of the DRD2 rs2283265 gene variant had more severe parent-reported depression symptoms compared to heterozygotes (Gadow et al. 2014a).

It is likely that certain demographic characteristics influence the presentation of depression in children with ASD. Gadow et al. (2016) reported correlations between a variety of child characteristics and impairing depression in a sample of clinic-referred youth with ASD. Parents (n = 214) and teachers (n = 174) completed the appropriate version of the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4R (CASI-4R; Gadow and Sprafkin 2010) as a measure of youths’ (aged 6–18 years, n = 221) depression symptom-induced impairment (i.e., the degree to which the behaviors interfere with daily functioning). It was found that parent-completed CASI-4R ratings for a major depressive episode (MDE) were associated with IQ and medication status, such that children with IQs ≥ 70 and those on psychotropic medication had more parent-reported impairment from a MDE. Teacher-completed CASI-4R ratings were associated with birth season, maternal education, medication status, and history of hospitalization, such that children born in the fall, those with less-educated mothers, those not on psychotropic medication, and those without a history of hospitalization had more teacher-reported impairment from a MDE. There was little evidence of concordance in parents’ and teachers’ ratings, and observed correlations were small (p < 0.10 or p < 0.05), which suggests that perceptions of depression-induced impairment in youth with ASD may be associated with a number of variables. Nonetheless, some of these results are consistent with earlier studies, such as the finding that ASD children of at least average intellectual functioning exhibited more severe depressive symptomatology than children with ASD and intellectual disability (Chandler et al. 2016; Fung et al. 2015).

With regard to gender, Gadow et al. (2016) found no main effect; however, there appears to be little expert agreement on gender’s impact on symptoms of depression in youth with autism. Several studies report no effect of gender (e.g., Chandler et al. 2016; Solomon et al. 2012), while others report more severe depression symptoms in males (Gotham et al. 2015) or females (Oswald et al. 2016). Oswald et al. (2016), for example, found that early adolescent females with ASD reported greater depression symptoms than age-matched males with ASD. Participants included 32 higher-functioning youth (12–17 years old) with autism. Depression was assessed via parent report, with the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale-Parent Version (Chorpita et al. 2000), and self-report, with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff 1977). Both measures revealed a significant three-way interaction, such that females with ASD exhibited more severe depression symptoms than males with ASD, but only during early adolescence. By during late adolescence, depression ratings for boys and girls were not significantly different.

In contrast, Gotham et al. (2015) reported that boys with ASD had greater symptoms of depression in early adolescence. Gotham et al. (2015) examined the depressive symptom trajectories of a large cohort of youth with ASD (n = 109) and nonspectrum developmental delay (DD; n = 56) from school age through young adulthood. Parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001), Adult Behavior Checklist (Achenbach and Rescorla 2003), or Developmental Behavior Checklist (Einfeld and Tonge 2002) depression subscales, according to child age and intellectual functioning, approximately every 3–6 months when their children were between the ages of 9 and 24. In the ASD group, males had more severe depressive symptoms than females at age 13; however, females exhibited greater symptom increases throughout adolescence, which resulted in no gender differences by age 21. Additionally, when controlling for verbal IQ, ASD diagnosis was associated with more severe depression symptoms than DD diagnosis.

Symptoms of depression are associated with a host of other physical (e.g., Richdale and Baglin 2015) and psychological (e.g., Storch et al. 2012) problems, including emotional dysregulation (e.g., Pouw et al. 2013), anxiety (e.g., Kerns et al. 2015), and suicidality (e.g., Storch et al. 2013) in youth with ASD. Due to the potential for loss of life, the finding that suicidal thoughts and behaviors were significantly more common in children with ASD, particularly those with comorbid major depressive disorder (Storch et al. 2013), than TD children (Mayes et al. 2013) should spur further research in this area.

Mayes et al. (2013) examined the frequency of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in a large sample of children with ASD (n = 791), TD children (n = 186), and depressed children without ASD (n = 35). Based on parental report, the percent of youth with autism for which suicidality was a problem was 10.9% for ideation and 7.2% for attempts. The percentage of children with ASD that had a problem with suicidal ideation or attempts was 28 times greater than the percentage for TD children (0.5%), but three times less than the percentage for depressed children without ASD (42.9%). In addition, Mayes et al. (2013) examined predictors of suicidality in their ASD sample, and it was found that depression, impulsivity, mood dysregulation, age ≥ 10, and race (i.e., Black or Hispanic) were significant predictors of suicidality in this group. Together, these identifiers classified children with versus without suicidal thoughts or behaviors with 87.8% accuracy; however, classification accuracy for ASD youth using the depression score alone was 87.1%, very close to that using all five significant predictor variables.

Also common in children with autism and depressive symptoms is emotional dysregulation. Emotion regulation (ER) refers to all processes that increase, decrease, or maintain the intensity of an internal feeling state (Mazefsky et al. 2014). One particular type of ER is coping, which refers to cognitive and behavioral efforts to modulate response to negative emotion-evoking situations. Coping strategies can be broadly divided into three types: approach (e.g., attempting to solve the problem), avoidant (e.g., distracting oneself from the problem), and maladaptive (e.g., thinking repeatedly about the problem without coming any closer to a solution); these three strategies have differential effects on the severity of depression symptomatology in those with and without ASD (Rieffe et al. 2014). Rieffe et al. (2014) examined the relationship between the three coping strategies and symptoms of depression in children with ASD (n = 81) and TD children (n = 131) of similar age (9–15 years old) and IQ. In both groups, approach and avoidant coping strategies were associated with less depression symptoms and maladaptive coping strategies were associated with more depression symptoms.

Given the prevalence and severity of symptoms of depression in youth with ASD, several studies have investigated which core features of ASD are associated with those symptoms (e.g., Bitsika and Sharpley 2016a; Bitsika et al. 2016b). In a study conducted by Bitsika and Sharpley (2016a), parents of 90 pre-adolescent and 60 adolescent males with ASD completed the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS; Constantino and Gruber 2012) and the CASI-D (Gadow and Sprafkin 2010). It was found that the SRS total score was significantly correlated with the CASI-D total score for both age groups. Also, CASI-D scores for both groups were associated with scores on four of the five SRS subscales: Social Cognition, Social Communication, Social Motivation, and Autistic Mannerisms. In contrast, Hollocks et al. (2014) did not find a significant correlation between social cognition and depression in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. This may be due to the way in which social cognition was operationally defined by the researchers. Hollocks et al. (2014) used laboratory measures to assess areas of social cognitive ability, whereas Bitsika and Sharpley (2016a) used parent report.

Stratis and Lecavalier (2013) focused on the relationship between restricted and repetitive behaviors and co-occurring depression in ASD. Parents of 72 young people with ASD (5–17 years old) completed the Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R; Bodfish et al. 1999) and an abridged version of the Child Symptom Inventory-4 (Gadow and Sprafkin 2002). Analyses revealed that the RBS-R Ritualistic/Sameness Behavior positively predicted depression symptom severity, and the RBS-R Restricted Interests negatively predicted depression symptom severity. Clarifying the relationships between depression and specific features of ASD could elucidate potential pathways for intervention, as decreases in autism symptom severity have been found to be associated with decreases in depression symptom severity (Andersen et al. 2015).

Treatment

To the authors’ knowledge, large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for treatment of depression in youth with comorbid ASD have not been conducted. In addition, the few treatment studies included in this review had several limitations. Sample sizes were relatively small (ranging from 1 to 47). The age range of participants was largely restricted to adolescents. Young people with below average IQ, as well as young people exhibiting suicidality, were excluded. Given these limitations, caution should be taken before generalizing the results of these investigations to the broad range of clinical presentations of depression in youth with autism spectrum disorder.

Although there is a dearth of studies evaluating treatment of depression in youth with ASD, much research has investigated the efficacy of treatment for major depressive disorder in young people without comorbid ASD. Evidence-based treatments for pediatric depression include psychotherapy, predominantly with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and pharmacotherapy, predominantly with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI; for review, see Cheung et al. 2013), and evidence suggests that combination therapy with CBT and a SSRI is superior to monotherapy with either (March et al. 2004).

Santomauro et al. (2016) reported the results of a pilot RCT of a group cognitive behavioral intervention for depression in cognitively higher-functioning adolescents with ASD. Participation required a verbal IQ (VIQ) of at least 85 and a documented diagnosis of ASD, but autism diagnosis was not reconfirmed by the researchers. The intervention was designed by Attwood and Garnett (2013) and called exploring depression: cognitive behavioral therapy to understand and cope with depression. The treatment protocol consisted of 10 weekly sessions and a final booster session conducted 4 weeks later. The sessions, conducted in a group setting with three to four participants per group, explored different strategies for depression symptom management. Each strategy was represented by a hardware tool, and strategies included physical, relaxation, pleasure, thinking, social, and self-awareness tools. In the intervention group, self-reported depression symptoms significantly decreased from baseline to 4 weeks post intervention according to both the Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck et al. 1996) and the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (Lovibond and Lovibond 1995); however, at 3 months post intervention, scores on both scales were no longer significantly different from baseline. This suggests that, in future studies, a greater emphasis is needed during and after the program on maintenance of learned strategies. In addition, future studies should consider the potential impact of pharmacological treatment on patients’ response to psychotherapy. Santomauro et al. (2016) did not comment on participants’ medication status during or after the CBT intervention period.

Santomauro et al. (2016) aimed to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, in addition to its preliminary efficacy. The primary barrier to feasibility was the difficulty recruiting eligible participants. Although the study was well advertised in schools, clinics, and autism associations, response rates were lower than expected, given the evidence of need; furthermore, of the 42 individuals assessed for eligibility, only 23 met the inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion included minimal depression symptoms, VIQ < 85, and high suicide risk. Of the adolescents initially assessed for eligibility, 19% were subsequently excluded due to suicidal ideation or hospitalization for self-harming behavior. In a population that is already difficult to engage, less prohibitive inclusion criteria may be necessary for sufficient recruitment for a large-scale RCT. Despite the study’s challenges, it appeared that the treatment program was acceptable to participants once initiated. Attendance was 100%, and only one family withdrew from the program prematurely. Also, a high proportion of adolescents reported to enjoy the program.

Results from a RCT of a social skills training program support the position that addressing core ASD symptoms can improve symptoms of depression. Yoo et al. (2014) evaluated the efficacy of a Korean version of PEERS® (Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills) in a sample of high-functioning adolescents between 12 and 18 years of age with ASD. ASD diagnosis was corroborated by board-certified child psychiatrists according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association 2000). PEERS® is a manualized, parent-assisted social skills training program that addresses crucial areas of social functioning for teens, such as choosing appropriate friends and handling disagreements. Post RCT, the intervention group (n = 23) showed significant improvement in interpersonal skills on a variety of measures, including the Social Responsiveness Scale (Constantino and Gruber 2012), as compared to the waitlist control group (n = 24). In addition, self-reported depression scores on the Children’s Depression Inventory (Kovacs 1982) significantly improved from pre-treatment to post-treatment. Notably, these improvements were maintained at a 3-month follow-up. These findings suggest that ASD teens’ emotional state, including depressive symptoms, may be positively impacted by social skills interventions that do not directly address emotional challenges.

A case study by Loades (2015) of a 17-year-old girl with autism spectrum disorder, chronic pain, anxiety, and depression illustrates the potential utility of a transdiagnostic framework in the treatment of multiple comorbidities. The cognitive model of self-esteem (Fennell 1998) was utilized due to its inclusion of maintenance cycles for both anxiety and depression. The model postulates that global negative beliefs about the self, which arise from an interaction between inborn temperamental factors and subsequent experience, are central to low self-esteem. Over the patient’s 20 weekly CBT sessions, the treatment aimed to weaken negative core beliefs and strengthen more positive beliefs about the self. Adaptations were made for ASD, including repetition of material and use of visual aids. Additionally, the clinician incorporated social skills and emotion recognition training into the protocol to address deficits central to ASD that could act as barriers to treatment. At the end of the treatment period, the patient reported scores on the Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS; Chorpita et al. 2000) significantly below those endorsed at baseline. This decrease appeared to reach clinical significance as her RCADS depression subscale score was within the clinical range pre intervention, but below the clinical range post intervention. It should also be noted that the patient was on a stable dose of a SSRI throughout psychotherapy.

Although psychopharmacological treatment is becoming increasingly common for low mood in individuals with ASD, little systematic research has focused on the use of antidepressant medications in persons with autism (Ghaziuddin et al. 2002). Golubchik et al. (2013) conducted an open-label trial of reboxetine (4 mg/daily), a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, to treat symptoms of depression and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in 11 child and adolescent patients with ASD. In this study, autism spectrum disorder diagnosis was affirmed by a certified child and adolescent psychiatrist. The exclusion criteria were current or past significant medical/neurological condition, intellectual disability, suicidality, violent behavior, and treatment with an antipsychotic, anticonvulsant, lithium, or antidepressant. Golubchik et al. (2013) did not comment on whether participants were in psychotherapy during the medication trial. After the 12-week trial period, a significant decrease in total Children’s Depression Rating Scale (CDRS; Poznanski et al. 1984) score was obtained at the group level, and patients with higher baseline CDRS scores showed a trend toward larger response to reboxetine. As a significant positive correlation was observed between changes in severity of depression and ADHD symptoms, it should be noted that patients’ ADHD symptoms, assessed by the Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Rating Scale (DuPaul et al. 1998), also improved. Most participants (91%) reported adverse effects, but all were tolerable and none required termination of treatment. Nonetheless, the frequency of adverse effects suggests that treatment with reboxetine for depressive symptoms in youth with ASD would require close monitoring.

Discussion

Although depression is common in youth with ASD, there appears to be little expert agreement on its prevalence. In this review, observed prevalence rates varied significantly from 7% (Orinstein et al. 2015) to 47.1% (Bitsika and Sharpley 2015), likely due to differences in sample characteristics and method(s) of assessment across studies. Samples were relatively small, and convenience sampling from clinic-referred populations was common. Only two prevalence studies utilized the same method of assessment for depression (i.e., Caamaño et al. 2013; Orinstein et al. 2015), yet even these two studies reported significantly different prevalence rates (14% versus 7%, respectively). To prevent selection bias and establish true prevalence and incidence rates of MDD in youth with ASD, large-scale, longitudinal population-based studies should be conducted.

Given the association of depression with other medical and psychiatric conditions, such as suicidality, in young people with ASD, accurate assessment is crucial; however, there is no gold standard measure for the assessment of symptoms of psychopathology in children with ASD (Kraemer et al. 2003; Stewart et al. 2006). This necessitates data collection from multiple methods of assessment (e.g., clinical interview, behavioral observation, and self-report and other reports) and informants, including the client, parent(s), teacher(s), and clinician(s). It seems that cognitively higher-functioning children with ASD can accurately self-report their internal feeling states (Ozsivadjian et al. 2014; Sterling et al. 2015); therefore, existing depression self-report measures, such as the Children’s Depression Inventory (Kovacs 1982), may be suitable for this population (Ozsivadjian et al. 2014). Nonetheless, there appears to be a lack of expert consensus on which depression screening measures are best for use with higher-functioning youth with ASD. Future studies should compare rating scales to determine which is superior at assessing symptoms of depression in children and adolescents with autism. Also, some children with ASD have limited functional communication skills and would be unable to provide a self-report of emotional problems. As such, future studies should consider other potential methods of depression assessment, including physiological and behavioral measures.

Although MDD is common in youth with ASD and has been the topic of much research, few intervention studies have been conducted; furthermore, to the authors’ knowledge, no large-scale RCTs have been conducted. Of the RCTs for treatment of youth depression to date, many have listed ASD as an exclusion criterion (e.g., Brent et al. 2008; March et al. 2004). Results from the treatment studies discussed in this review, as well as in previous reviews (e.g., Stewart et al. 2006), suggest that some pharmacological and psychosocial treatments could be efficacious. A norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, reboxetine, significantly reduced symptoms of depression in a small sample of young patients with ASD (Golubchik et al. 2013); however, in non-ASD individuals with depression, SSRIs demonstrate significantly superior response rates and fewer adverse effects compared to reboxetine (Eyding et al. 2010). In a small-scale randomized controlled trial of CBT for depression in adolescents with ASD, significant improvements in depression scores were reported at 4 weeks post intervention, but gains were not maintained at 3 months post intervention (Santomauro et al. 2016). This suggests that CBT for depression may be efficacious in this population, but future intervention studies should include a module on the maintenance of learned strategies. Given that combination therapy with CBT and a SSRI has demonstrated superior efficacy to monotherapy with either in youth without ASD (March et al. 2004), this treatment protocol should be systematically evaluated in youth with autism in a large-scale RCT. The results of a case study conducted by Loades (2015) provide preliminary support for combination treatment with CBT and a SSRI for depression in youth with ASD. After the participant’s 20 weekly CBT sessions while on a stable dose of a SSRI, the patient reported significantly lower depression symptom scores than those endorsed at baseline.

The purpose of this systematic review was to provide an overarching summary of the recent empirical research on the prevalence, presentation, and treatment of depression symptoms in youth with ASD by surveying studies published on the topic between 2012 and 2016. Due to the considerable amount of research on this topic in recent years, it would not have been feasible to include all published studies since the last systematic review (i.e., Stewart et al. 2006); nonetheless, this systematic review provides a much-needed update on an area of research that has received much attention in the last several years.

As with all systematic reviews, this review is limited by the study design quality of the available studies. Sample sizes were relatively small and homogeneous. Future studies should have larger samples and include girls, racial/ethnic minority participants, and individuals with intellectual disability, as these groups have been understudied to date. Several studies did not confirm ASD diagnosis (e.g., Ozsivadjian et al. 2014; Solomon et al. 2012; Yoo et al. 2014). In future research, investigators should affirm diagnosis of ASD using empirically validated assessment measures (for review, see Ozonoff et al. 2005) to ensure honesty and accuracy in research reporting. There was little consistency in the method of depression symptom assessment across studies. More research is needed on the validity and reliability of depression measures in children with ASD, particularly in lower-functioning children, as accurate assessment is crucial to appropriate diagnosis and treatment planning. Unfortunately, the evidence base for treatment of depression in children and adolescents with ASD is quite sparse. Although it appears that some psychosocial and pharmacological treatments may be effective, more research in this area is sorely needed.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. (2001). ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington: ASEBA.

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. (2003). ASEBA adult forms & profiles: for ages 18-59: Adult self-report and adult behavior checklist. ASEBA.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual, 4th edn, text revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric.

Amr, M., Raddad, D., El-Mehesh, F., Bakr, A., Sallam, K., & Amin, T. (2012). Comorbid psychiatric disorders in Arab children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 240–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.05.005.

Andersen, P. N., Skogli, E. W., Hovik, K. T., Egeland, J., & Øie, M. (2015). Associations among symptoms of autism, symptoms of depression and executive functions in children with high-functioning autism: a 2 year follow-up study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(8), 2497–2507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2415-8.

Attwood, T., & Garnett, M. (2013). Exploring depression: Cognitive behaviour therapy to understand and cope with depression. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Baio, J., Wiggins, L., Christensen, D. L., Maenner, M. J., Daniels, J., Warren, Z., et al. (2018). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 67(6), 1.

Bauman, M. L. (2010). Medical comorbidities in autism: challenges to diagnosis and treatment. Neurotherapeutics, 7(3), 320–327.

Beck, J. (2005). Beck youth inventories—second edition for children and adolescents manual. San Antonio: PsychCorp.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, 78(2), 490–498.

Birmaher, B., Ryan, N. D., Williamson, D. E., Brent, D. A., Kaufman, J., Dahl, R. E., et al. (1996). Childhood and adolescent depression: a review of the past 10 years. Part I. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 35(11), 1427–1439.

Bitsika, V., & Sharpley, C. F. (2015). Differences in the prevalence, severity and symptom profiles of depression in boys and adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder versus normally developing controls. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 62(2), 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2014.998179.

Bitsika, V., & Sharpley, C. F. (2016a). The association between social responsivity and depression in high-functioning boys with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 28(2), 317–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-015-9470-0.

Bitsika, V., & Sharpley, C. F. (2016b). Mothers’ depressive state ‘distorts’ the ratings of depression they give for their sons with an autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 63(5), 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2016.1144875.

Bitsika, V., Sharpley, C. F., Andronicos, N. M., & Agnew, L. L. (2016a). Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal-axis associations with self- vs. parental ratings of depression in boys with an autism spectrum disorder. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 15(1), 69–75.

Bitsika, V., Sharpley, C. F., & Mills, R. (2016b). Are sensory processing features associated with depressive symptoms in boys with an ASD? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(1), 242–252.

Bodfish, J., Symons, F., & Lewis, M. (1999). The repetitive behavior scale. Western Carolina Center Research reports.

Brent, D., Emslie, G., Clarke, G., Wagner, K. D., Asarnow, J. R., Keller, M., et al. (2008). Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression: the TORDIA randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 299(8), 901–913.

Caamaño, M., Boada, L., Merchán-Naranjo, J., Moreno, C., Llorente, C., Moreno, D., et al. (2013). Psychopathology in children and adolescents with ASD without mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(10), 2442–2449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1792-0.

Chandler, S., Howlin, P., Simonoff, E., O’Sullivan, T., Tseng, E., Kennedy, J., et al. (2016). Emotional and behavioural problems in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 58(2), 202–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.12830.

Cheung, A. H., Kozloff, N., & Sacks, D. (2013). Pediatric depression: an evidence-based update on treatment interventions. Current Psychiatry Reports, 15(8), 381.

Chorpita, B. F., Yim, L., Moffitt, C., Umemoto, L. A., & Francis, S. E. (2000). Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: a revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(8), 835–855.

Constantino, J. N., & Gruber, C. P. (2012). Social responsiveness scale (SRS). Torrance: Western Psychological Services.

DuPaul, G., Power, T., Anastopoulos, A., & Reid, R. (1998). ADHD Rating Scale-IV. Checklists, norms and clinical interpretation. New York: Guilford Google Scholar.

Einfeld, S. L., & Tonge, B. J. (2002). Manual for the developmental behaviour checklist: Primary carer version (DBC-P) & teacher version (DBC-T). University of New South Wales and Monash University.

Eyding, D., Lelgemann, M., Grouven, U., Härter, M., Kromp, M., Kaiser, T., et al. (2010). Reboxetine for acute treatment of major depression: systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished placebo and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor controlled trials. BMJ, 341, c4737.

Fennell, M. J. (1998). Cognitive therapy in the treatment of low self-esteem. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 4(5), 296–304.

Fung, S., Lunsky, Y., & Weiss, J. A. (2015). Depression in youth with autism spectrum disorder: the role of ASD vulnerabilities and family–environmental stressors. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 8(3–4), 120–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2015.1017892.

Gadow, K. D., & Sprafkin, J. N. (2002). Child Symptom Inventory 4: Screening and norms manual. Checkmate Plus.

Gadow, K., & Sprafkin, J. (2010). Child and adolescent symptom inventory 4R: Screening and norms manual. Stony Brook: Checkmate Plus.

Gadow, K. D., Devincent, C. J., Pomeroy, J., & Azizian, A. (2005). Comparison of DSM-IV symptoms in elementary school-age children with PDD versus clinic and community samples. Autism, 9(4), 392–415.

Gadow, K. D., Guttmann-Steinmetz, S., Rieffe, C., & DeVincent, C. J. (2012). Depression symptoms in boys with autism spectrum disorder and comparison samples. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(7), 1353–1363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1367-x.

Gadow, K. D., Pinsonneault, J. K., Perlman, G., & Sadee, W. (2014a). Association of dopamine gene variants, emotion dysregulation and ADHD in autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(7), 1658–1665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.04.007.

Gadow, K. D., Smith, R. M., & Pinsonneault, J. K. (2014b). Serotonin 2A receptor gene (HTR2A) regulatory variants: possible association with severity of depression symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology, 27(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNN.0000000000000028.

Gadow, K. D., Perlman, G., Ramdhany, L., & Ruiter, J. (2016). Clinical correlates of co-occurring psychiatric and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) symptom-induced impairment in children with ASD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(1), 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-9979-9.

Ghaziuddin, M., Ghaziuddin, N., & Greden, J. (2002). Depression in persons with autism: implications for research and clinical care. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32(4), 299–306.

Gjevik, E., Sandstad, B., Andreassen, O. A., Myhre, A. M., & Sponheim, E. (2015). Exploring the agreement between questionnaire information and DSM-IV diagnoses of comorbid psychopathology in children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 19(4), 433–442.

Goldin, R. L., Matson, J. L., Konst, M. J., & Adams, H. L. (2014). A comparison of children and adolescents with ASD, atypical development, and typical development on the Behavioral Assessment System for Children, Second Edition (BASC-2). Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(8), 951–957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.04.005.

Golubchik, P., Sever, J., & Weizman, A. (2013). Reboxetine treatment for autistic spectrum disorder of pediatric patients with depressive and inattentive/hyperactive symptoms: an open-label trial. Clinical Neuropharmacology, 36(2), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNF.0b013e31828003c1.

Gotham, K., Brunwasser, S. M., & Lord, C. (2015). Depressive and anxiety symptom trajectories from school age through young adulthood in samples with autism spectrum disorder and developmental delay. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(5), 369–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2015.02.005.

Hammond, R. K., & Hoffman, J. M. (2014). Adolescents with high-functioning autism: an investigation of comorbid anxiety and depression. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 7(3), 246–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2013.843223.

Hebron, J., & Humphrey, N. (2012). Mental health difficulties among young people on the autistic spectrum in mainstream secondary schools: a comparative study. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 14(1), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2012.01246.x.

Hollocks, M. J., Jones, C. R. G., Pickles, A., Baird, G., Happé, F., Charman, T., et al. (2014). The association between social cognition and executive functioning and symptoms of anxiety and depression in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Research, 7(2), 216–228. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1361.

Jaycox, L. H., Stein, B. D., Paddock, S., Miles, J. N., Chandra, A., Meredith, L. S., et al. (2009). Impact of teen depression on academic, social, and physical functioning. Pediatrics, 124(4), e596–e605.

Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Brent, D., Rao, U., Flynn, C., Moreci, P., et al. (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(7), 980–988.

Kerns, C. M., Kendall, P. C., Zickgraf, H., Franklin, M. E., Miller, J., & Herrington, J. (2015). Not to be overshadowed or overlooked: functional impairments associated with comorbid anxiety disorders in youth with ASD. Behavior Therapy, 46(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2014.03.005.

Kovacs, M. (1982). Children’s Depression Inventory—short version. North Tonawanda: Multi-Health Systems Inc..

Kraemer, H. C., Measelle, J. R., Ablow, J. C., Essex, M. J., Boyce, W. T., & Kupfer, D. J. (2003). A new approach to integrating data from multiple informants in psychiatric assessment and research: mixing and matching contexts and perspectives. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(9), 1566–1577.

Lainhart, J. E., Bigler, E. D., Bocian, M., Coon, H., Dinh, E., Dawson, G., et al. (2006). Head circumference and height in autism: a study by the Collaborative Program of Excellence in Autism. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 140(21), 2257–2274.

Le Couteur, A., Rutter, M., Lord, C., Rios, P., Robertson, S., Holdgrafer, M., et al. (1989). Autism diagnostic interview: a standardized investigator-based instrument. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 19(3), 363–387.

Lerner, M. D., Calhoun, C. D., Mikami, A. Y., & De Los Reyes, A. (2012). Understanding parent–child social informant discrepancy in youth with high functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(12), 2680–2692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1525-9.

Leyfer, O. T., Folstein, S. E., Bacalman, S., Davis, N. O., Dinh, E., Morgan, J., et al. (2006). Comorbid psychiatric disorders in children with autism: interview development and rates of disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(7), 849–861.

Loades, M. E. (2015). Evidence-based practice in the face of complexity and comorbidity: a case study of an adolescent with Asperger’s syndrome, anxiety, depression, and chronic pain. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 28(2), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12108.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (1994). Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24(5), 659–685.

Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook, E. H., Leventhal, B. L., DiLavore, P. C., et al. (2000). The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(3), 205–223.

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343.

Magnuson, K. M., & Constantino, J. N. (2011). Characterization of depression in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: JDBP, 32(4), 332.

March, J., Silva, S., Petrycki, S., Curry, J., Wells, K., Fairbank, J., et al. (2004). Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 292(7), 807–820.

Mayes, S. D., Gorman, A. A., Hillwig-Garcia, J., & Syed, E. (2013). Suicide ideation and attempts in children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(1), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2012.07.009.

Mazefsky, C. A., Borue, X., Day, T. N., & Minshew, N. J. (2014). Emotion regulation patterns in adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: comparison to typically developing adolescents and association with psychiatric symptoms. Autism Research, 7(3), 344–354. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1366.

Mazzone, L., Postorino, V., De Peppo, L., Fatta, L., Lucarelli, V., Reale, L., et al. (2013). Mood symptoms in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(11), 3699–3708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2013.07.034.

McConaughy, S. H., & Achenbach, T. M. (1994). Manual for the semistructured clinical interview for children and adolescents. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097.

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., et al. (2015). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1.

Orinstein, A., Tyson, K. E., Suh, J., Troyb, E., Helt, M., Rosenthal, M., et al. (2015). Psychiatric symptoms in youth with a history of autism and optimal outcome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(11), 3703–3714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2520-8.

Oswald, T. M., Winter-Messiers, M. A., Gibson, B., Schmidt, A. M., Herr, C. M., & Solomon, M. (2016). Sex differences in internalizing problems during adolescence in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(2), 624–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2608-1.

Ozonoff, S., Goodlin-Jones, B. L., & Solomon, M. (2005). Evidence-based assessment of autism spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(3), 523–540.

Ozsivadjian, A., Hibberd, C., & Hollocks, M. J. (2014). Brief report: the use of self-report measures in young people with autism spectrum disorder to access symptoms of anxiety, depression and negative thoughts. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(4), 969–974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1937-1.

Pouw, L. B. C., Rieffe, C., Stockmann, L., & Gadow, K. D. (2013). The link between emotion regulation, social functioning, and depression in boys with ASD. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(4), 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.01.002.

Poznanski, E. O., & Mokros, H. B. (1996). Children’s Depression Rating Scale, revised (CDRS-R). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Poznanski, E. O., Grossman, J. A., Buchsbaum, Y., Banegas, M., Freeman, L., & Gibbons, R. (1984). Preliminary studies of the reliability and validity of the Children’s Depression Rating Scale. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 23(2), 191–197.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

Richdale, A. L., & Baglin, C. L. (2015). Self-report and caregiver-report of sleep and psychopathology in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: a pilot study. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 18(4), 272–279. https://doi.org/10.3109/17518423.2013.829534.

Rieffe, C., De Bruine, M., De Rooij, M., & Stockmann, L. (2014). Approach and avoidant emotion regulation prevent depressive symptoms in children with an autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience, 39, 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2014.06.003.

Santomauro, D., Sheffield, J., & Sofronoff, K. (2016). Depression in adolescents with ASD: a pilot RCT of a group intervention. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(2), 572–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2605-4.

Schniering, C. A., & Rapee, R. M. (2002). Development and validation of a measure of children’s automatic thoughts: the children’s automatic thoughts scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(9), 1091–1109.

Sharpley, C. F., Bitsika, V., Andronicos, N. M., & Agnew, L. L. (2016). Further evidence of HPA-axis dysregulation and its correlation with depression in autism spectrum disorders: data from girls. Physiology & Behavior, 167, 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.09.003.

Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., & Baird, G. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(8), 921–929.

Solomon, M., Miller, M., Taylor, S. L., Hinshaw, S. P., & Carter, C. S. (2012). Autism symptoms and internalizing psychopathology in girls and boys with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(1), 48–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1215-z.

Sterling, L., Renno, P., Storch, E. A., Ehrenreich-May, J., Lewin, A. B., Arnold, E., et al. (2015). Validity of the Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale for youth with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 19(1), 113–117.

Stewart, M. E., Barnard, L., Pearson, J., Hasan, R., & O’Brien, G. (2006). Presentation of depression in autism and Asperger syndrome: a review. Autism, 10(1), 103–116.

Storch, E. A., Larson, M. J., Ehrenreich-May, J., Arnold, E. B., Jones, A. M., Renno, P., et al. (2012). Peer victimization in youth with autism spectrum disorders and co-occurring anxiety: relations with psychopathology and loneliness. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 24(6), 575–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-012-9290-4.

Storch, E. A., Sulkowski, M. L., Nadeau, J., Lewin, A. B., Arnold, E. B., Mutch, P. J., et al. (2013). The phenomenology and clinical correlates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(10), 2450–2459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1795-x.

Strang, J. F., Kenworthy, L., Daniolos, P., Case, L., Wills, M. C., Martin, A., et al. (2012). Depression and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders without intellectual disability. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 406–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.06.015.

Stratis, E. A., & Lecavalier, L. (2013). Restricted and repetitive behaviors and psychiatric symptoms in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(6), 757–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.02.017.

Tudor, M. E., DeVincent, C. J., & Gadow, K. D. (2012). Prenatal pregnancy complications and psychiatric symptoms: children with ASD versus clinic controls. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(4), 1401–1405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2012.06.001.

Wing, L. (1981). Asperger’s syndrome: a clinical account. Psychological Medicine, 11(1), 115–129.

Yoo, H. J., Bahn, G., Cho, I. H., Kim, E. K., Kim, J. H., Min, J. W., et al. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of the Korean version of the PEERS® parent-assisted social skills training program for teens with ASD. Autism Research, 7(1), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1354.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Menezes, M., Robinson, L., Sanchez, M.J. et al. Depression in Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders: a Systematic Review of Studies Published Between 2012 and 2016. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 5, 370–389 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-018-0146-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-018-0146-4