Abstract

Purpose of Review

The review sought to present research pertaining to gambling and homelessness. Findings mapping the prevalence of disordered gambling within the homeless and those exploring the bi-directional nature of the relationship are discussed. The review explores theoretical explanations for the appeal of gambling to homeless individuals and discusses future directions.

Recent Findings

Research indicates the prevalence of disordered gambling is significantly higher in the homeless, comparable to the general population. Further research indicates that gambling is more commonly a factor contributing to homelessness, that gambling disorders are often overlooked by homeless services, and that support services are often inadequate.

Summary

Disordered gambling is common in homelessness; however, the relationship is bi-directional. Gambling can be a direct cause of homelessness, a secondary contributing factor, or only develop after the individual has become homeless. Potential for significant life change is a motivating factor for gambling; for a homeless individual, a small win could be the difference between eating and not eating, or between sleeping in a hostel or on the street. Homeless services can provide a platform for problem identification and direction to the provision of support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The act of gambling is thought to contain three fundamental components: consideration, risk and a prize [1], and is a common activity that is evident across history, societies and cultures [2]. Gambling is often portrayed as glamorous and harmless, whilst gambling marketing places the dream of untold rewards tantalisingly within the individual’s reach. There are many different forms of gambling available, ranging from traditional forms such as slot machines, horse racing and lotteries etc., to more contemporary forms including skins gambling and virtual sports. The continued growth of online gambling provision has facilitated the evolution of traditional forms of gambling such as sports betting, through the development of newer features such as in-play betting [3] and cash-out (where all or part of winnings due can be withdrawn before the bet has reached a conclusion) [4]. Repeated exposure to gambling through advertising and sports team and event sponsorship can serve to normalise gambling [5, 6], serving to thoroughly assimilate gambling within mainstream culture. Although the majority of gamblers do so recreationally without generating negative consequences, the harms experienced by those for whom gambling becomes a maladaptive behaviour include elevated psychiatric comorbidity and poor mental health [7•, 8], increased likelihood of alcohol use disorders [9] and substance use disorders [10], elevated suicidal tendencies [11], and an increased likelihood to be involved in domestic violence [12].

Gambling and Homelessness

A further harm associated with disordered gambling is homelessness. It is well understood that the causes of homelessness can be numerous and complex, and that an individual’s sleeping status can be influenced by a multitude of factors ranging from their own behaviours and choices to government legislation well beyond the control of the individual [13]. Sleeping status refers to where an individual is currently sleeping e.g. rough sleeping on the street, in temporary accommodation, such as a hostel or supported housing, or any other status including squatting and sofa surfing, among others. Factors identified as causing homelessness include relationship breakdown, drug and alcohol problems, being asked to leave the family home, leaving an institutional environment such as prison, job loss, mental health problems, domestic violence, eviction and problems with benefit payments [14]. Gambling can also contribute to an individual becoming homeless, although the relationship is not always as clear as with other factors. In some instances, homelessness can be a direct result of gambling, for example, when the individual faces eviction for non-payment of rent. However, in some instances, the influence of gambling is more subtle; although family disagreements and relationship breakdown are regularly cited as causes of homelessness, the factors behind the arguments that resulted in relationship breakdown, which can often include gambling, are rarely documented or considered. Therefore, the influence of gambling in some instances is more nuanced.

Prevalence of Disordered Gambling in Homeless Populations

A limited number of studies have directly investigated the prevalence of disordered gambling in samples of homeless individuals, primarily from the UK and North America (Table 1). For those that have, despite some methodological differences (discussed later), the consistent finding is that the prevalence of disordered gambling is higher in the homeless samples than in the relevant general population. The earliest two major studies to directly measure gambling problems in the homeless came from Canada and the USA. In Canada, using the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) [25] in a sample of individuals relying on community assistance for survival, a study found a probable pathological gambling rate of 17.2%, and a prevalence of problem gambling (a less severe classification using the SOGS) of 12.6% [15]. The study also found that 60% of pathological gamblers were not aware of any specialised gambling support services. In the USA, a further study recruited homeless persons accessing a substance use disorder programme and using the Massachusetts Gambling Screen (MAGS) [26], classified individuals as either level 1 (asymptomatic), level 2 (experienced any adverse symptoms) or level 3 (pathological). The results showed prevalence of level 3 gambling at 5.5%, and level 2 at 12.8%. The study also reported that level 3 gamblers had been homeless significantly more often than any other group, and level 2 gamblers had been homeless more than non-gamblers. Level 3 gamblers were more likely to have a history of psychiatric problems and were less likely to complete drug and alcohol detoxification services [17•].

In 2014, two further North American studies sought measure the prevalence of disordered gambling in the homeless. Using the SOGS, a study from the USA reported a lifetime prevalence of disordered gambling of 12%, with a further 46.2% experiencing subclinical problems in a sample of predominantly African-American males. Furthermore, the study found that problem gamblers were more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anti-social personality disorder (ASPD), and that gambling prevalence in the homeless sample was significantly higher than the general population in the same geographic area [19]. Furthermore, using the NORC diagnostic screen for disorders (NODS) [27] and the NODS CLiP [28], a study in Toronto homeless shelters reported lifetime pathological prevalence of 25%, and lifetime problem gambling prevalence of 10%, in a sample of community homeless service agency clients. Within those that disclosed any gambling, 58% were lifetime pathological gamblers; 22.3% were classified as problem gamblers, and 19.6% were at risk gamblers, indicating prevalence increased in line with severity classification [20•].

Research from the UK has also indicated that gambling problems are more prevalent in the homeless than the general population. Recruiting the largest sample to date looking specifically at gambling problems in the homeless population, one study used the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) [29], to measure gambling problems and found the prevalence of problem gambling was 11.6% [22•]. Further analysis of the risk category distribution of the participants demonstrated a differing pattern of gambling engagement between homeless gamblers, and the general population, as reported in the British Gambling Prevalence Survey (BGPS [23]). Within the general population, the risk category distribution shows a stepwise trend, with prevalence decreasing as risk increased [23]. However, within the homeless population, the prevalence of problem gamblers was higher than the low risk or moderate risk categories, indicating that engagement with gambling tends to be minimal, or problematic (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, this pattern was also evident when only analysing those who registered any level of risk on the PGSI (i.e. a score of > 0); any-risk gamblers in the general population demonstrate the same downward stepwise pattern as when considering all participants. Within the homeless any-risk gamblers, the opposite was observed, with the highest proportion of any risk gamblers falling in the most severe classification (Fig. 1b) [22•]. Exploring this relationship further, a further UK study in a smaller sample found PGSI problem gambling in 23.6% of homeless participants. The study also sought to ascertain whether gambling was more commonly a cause of homelessness, or a behaviour that only became problematic post-homelessness, and found that gambling more commonly preceded homelessness. However, in a number of cases, gambling problems emerged secondary to homelessness [24•]. This result indicated that it is perhaps an oversimplification of a complex relationship to infer simply that gambling causes homelessness, rather can also be utilised as a coping strategy, or viewed as a pathway out of an individual’s current life circumstance.

A further study in Japan investigating cognitive impairment in homelessness also reported an elevated level of pathological gambling (31%); however, the study only recruited 16 participants, therefore does not allow for many conclusions to be drawn [30].

Gambling and Homelessness—a Complex Relationship

Although previous studies have sought to simply measure the prevalence of disordered gambling in homeless populations, some studies have sought to apply different research designs and analysis techniques to better understand the nature and direction of the relationship, associated costs and prevalence in specific populations. In the UK, a recent study that aimed to estimate the costs of disordered gambling to Government estimated that statutory homeless applications from individuals who are problem gamblers (including legal and administrative costs, and 4 weeks in temporary accommodation) cost the government between £10–60 million per annum [31•]. However, this figure may serve as an underestimation as definitions of homelessness can extend beyond statutory homelessness applications, and not all definitions, such as hidden homeless, were included in the cost analysis calculations. Furthermore, the cost calculations were not able to incorporate rapidly increasing costs of accommodation and were predicated on the assumption that the average stay in temporary accommodation is 4 weeks; however, previous research indicates that this period could be far longer than 4 weeks [32].

Other studies have sought to measure housing stability as a risk factor for gambling disorders; using a logistic regression analysis, one study found a significantly lower proportion of individuals living in stable accommodation reporting gambling problems, compared to individuals in unstable housing [33]. Applying logistic regression in a large sample of US veterans, a further study found that homelessness in the past year increased the odds ratio of a diagnosis of pathological gambling in veterans accessing a mental health program [34]. In a large US sample of over 42,000 individuals, participants were classified as a function of gambling severity. More severe gamblers were found more likely to have ever been homeless, indicating a relationship between homelessness and gambling severity, although it is unclear if the gambling and homelessness were causally related [35]. Although research has demonstrated increased prevalence of gambling problems in homeless samples, and that homelessness increases the risk of gambling disorders, other research encompassing a range of methodological approaches has reported that the converse relationship is evident, that gambling contributes to homelessness. Gambling was identified as a contributing factor to homelessness in a three-nation study conducted in the UK, the US and Australia [36], although it should be noted that gambling problems were more commonly identified as a contributing factor in the Australian branch of the study [37]. Similarly, a study in Amsterdam indicated that 18% of participants self-reported gambling problems prior to becoming homeless; of those who had been evicted, 24% reported gambling-related debts, implying a strong causal relationship [38]. More recently in the UK, a large study of male health and lifestyles found that problem gambling and probable pathological gambling were associated with homelessness, with both problem and pathological gamblers more likely to have experienced homelessness than non-gamblers, non-problem gamblers and borderline problem gamblers [39]. In Australia, data collected over 8.5 years from psychiatric clinics in inner Sydney homeless hostels reports that a key pathway in to homelessness is an inability to pay rent due to gambling [40].

Gambling and Co-Morbid Substance Use in Homelessness

Whilst the co-morbid relationships between disordered gambling and substance use [41, 42] and between substance use and homelessness [43, 44] have been well reported, the relationships between gambling and substance use in homelessness are less well researched, and findings are inconsistent. In a sample of homeless individuals seeking treatment for a substance misuse disorder, more severe gamblers were found to have less drug treatment programme engagement, and a lower completion rate of detoxification services than those with less severe gambling problems [17•]; however, another study reports that problem gamblers were more likely to use illicit drugs or meet criteria for abuse or dependence for nicotine, alcohol or any other substance [19]. In a study of the homeless in the UK, high rates of substance and alcohol use were reported: 70.8% of participants disclosed alcohol use (36.1% reported some level of risk), and 41.7% of participants reported using a substance other than alcohol or tobacco (38.9% indicating some level of risk). However, it is interesting to note that despite participants reporting a bi-modal engagement pattern of either not at all or maladaptive for both gambling and substance use, gambling did not correlate with drug or alcohol use [24•]. The over-representation of both disordered gambling and substance use disorders in the homeless population could be reflective of an underlying vulnerability characterised by increased impulsivity, sensation seeking and preference for immediate reward. Elevated impulsivity and immediate reward preference have previously been reported in both treatment-seeking problem gamblers [45], and substance and alcohol users [46,47,48]. However, to date, the role of impulsivity, sensation seeking and delay discounting in relation to substance use and disordered gambling in the homeless population has not been formally studied, indicating an interesting future direction for research. Atypical neuropsychological functioning notwithstanding, it is also possible that behaviour is influenced by practical and environmental factors, such as accessibility of substances and gambling availability. Furthermore, due to restricted or minimised income, the individual can be faced with a choice of behaviour; when income is received e.g. on benefit payment day in the UK, those with a predilection for gambling are able to gamble in the hope of gaining greater monetary reward which in turn can be used to purchase cigarettes, alcohol, and other substances. Conversely, those whose primary disorder relates to substances are reluctant to risk losing the money that they know is sufficient for their substance needs, so will therefore purchase substances before entertaining the thought of gambling, in effect becoming risk averse in order to preserve the ability to engage in an alternative risky behaviour [24•]. In such instances therefore, the primary disorder takes financial precedence.

Gambling and Homelessness—Poverty, Exposure, Hope

Poverty has long been a strong predictor of homelessness [49], and the psychological effect of poverty is profound. Research indicates that living in poverty can negatively impact economic decision-making and encourage risky and short-sighted choices [50•]. Unemployment often leads to financial hardship and poverty, and is an established and powerful predictor of homelessness [51]. Indeed, one UK study found that any-risk gamblers were significantly more likely to have experienced gambling problems and significant job loss than no-risk/non-gamblers [24•]. Disordered gambling and the associated harms are more commonly experienced by those who might be considered financially disadvantaged [52, 53]. However, many symptoms of disordered gambling are expressed as financial losses and the subsequent implications of financial loss and may therefore be biased to increase diagnosis in low-income individuals for whom a big loss can have catastrophic consequences. A wealthier individual may gamble as often and experience similar loss of control, however may avoid a diagnosis due to access to more financial reserves, avoiding severe negative consequences and thus a diagnosis. Higher levels of loss are experienced in areas of socioeconomic disadvantage [54], and a higher proportion of income is spent on gambling in lowest income households [55]. Some forms of gambling are clustered in more disadvantaged, low socioeconomic areas, particularly electronic gaming machines [56, 57], whilst people of lower financial status play lotteries more than those with greater financial means [58]. Furthermore, recent research investigating local area characteristics such as area disadvantage and genetic contributions to individual differences has shown that heritability of problematic gambling is greater in areas of local disadvantage, indicating that an interaction between genes and area locality contributes to the development and maintenance of disordered gambling [59].

The appeal of gambling to those who could be considered financially disadvantaged has been rationalised from a range of theoretical perspectives, including those that focus on societal structures such as social disorganisation and deprivation [60], and the impact of legislative frameworks resulting in social marginalisation and relative powerlessness [61]. Further theoretical perspectives are grounded in the mental health [62], neuropsychological functioning [63] and the economic endeavour [64] of the individual. The appeal of gambling to those experiencing poverty or financial hardship has also been attributed to the psychoeconomics of gambling [65•]. Rooted in the eighteenth century work of Daniel Bernoulli [66], p44–45] psychoeconomics refers to the potential magnitude for change relative to the individual; the life of a person of lesser means could be improved by a win to a greater extent than a win of the same amount would change the life of a person of greater means. This is particularly pertinent for an individual who is homeless, where perhaps a small win could be the difference between eating and not eating or sleeping in a hostel compared to sleeping on the street. Therefore, the potential for meaningful change is fundamental to the appeal of gambling to individuals of lesser means.

A recent study in the UK conducted interviews with 19 homeless gamblers, to better understand the complex relationship between gambling and homelessness. Although a variety of reasons were offered for continued gambling even after the individual had become homeless, the most commonly identified reason is one that supports the psychoeconomic theoretical perspective. Gamblers viewed gambling not only as a legitimate income source, but as an opportunity to radically alter their life in a single day, or with one single bet. Multiple participants describe gambling as their chance to escape from poverty, and to escape the cycle of homelessness. Furthermore, individuals describe how they paid little regard to future consequence, and how throughout the cycle of a gambling binge, the prospect of a life changing win evolved from expectation to hope, and finally to desperation and desolation [67•]. Although homeless gamblers do not have the monopoly on chasing ‘the’ big win, the potential for life change is greater for an individual of lesser means, than an individual of greater means, making gambling an eternally appealing option.

Practical Application and Methodological Difficulties

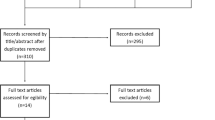

Investigating the relationship between gambling and homelessness, measuring the prevalence of disordered gambling, and comparing prevalence across studies is a task fraught with methodological complications. Studies have used a range of different instruments to measure gambling across different time frames (see Table 1), so could therefore be capturing different dimensions of gambling behaviour and consequently influencing prevalence estimates [68•]. Previous efforts to measure prevalence have highlighted methodological issues such as unrepresentative sample composition [15], and differences in the sleeping status of participants [17•] reducing the overall generalisability of results. Furthermore, in the six studies estimating prevalence discussed at length here, each study reported data from samples that were overwhelmingly male. Whilst a gender imbalance may be representative of the homeless population overall, it prohibits generalisation of findings. More work is needed for the prevalence and gambling behaviour of homeless females.

Although a growing body of literature identifies a relationship between gambling and homelessness, in the UK, the identification of, and support for, gambling disorders is still not routinely considered in most homeless services, with awareness and provision of treatment services for gambling disorders significantly lower than the equivalent services for substance misuse [24•]. Even when gambling is asked about and support services are available, homeless gamblers are unlikely to seek treatment due to shame, stigma and identity issues [69]. In a recent UK study, interviews with both homeless gamblers and homelessness practitioners identified a number of factors influential in the lack of identification, support and treatments seeking for gambling disorders, including services not even considering gambling as a potential factor in homelessness, lack of spontaneous disclosure from individuals, embarrassment and shame at suffering from what was considered a less serious problem (in relation to substance misuse), concerns over the financial impact of disclosing a gambling problem in relation to benefit claims, and superseding of gambling problems by other mental or physical health disorders [67•]. When an individual is unwilling to disclose, and the servicing agency is not actively looking, it is easy to see why gambling disorders can remain undetected.

Future Directions

In the UK, efforts are being made to reduce the influence of gambling on the cycle of homelessness. A recent study utilised consistent themes identified in interviews with homeless gamblers to develop a range of tools for both gamblers, and for homeless services [67•]. Following consultation with both homeless gamblers and homelessness practitioners, the revised tools included an information sheet for practitioners that briefly outlines what gambling is, why it should be asked about, what the appeal of gambling is, and what signs to look for as indicators of a possible problem and identifies some potential barriers to talking about gambling. The study also developed a population-specific screening tool to assist in the identification of those who might benefit from further support for gambling-related problems, and finally a resource sheet for the individual offering advice on what can be done immediately to reduce harm, and that provides details of both local and national support services [67•]. Furthermore, at least two homeless services within London now offer gambling support groups. Although shining a spotlight on gambling problems within the homeless from the perspective service providers is in its infancy, awareness of gambling problems and support pathways are increasing.

Conclusion

Research has shown that gambling disorder prevalence is higher in homeless populations than country equivalent national prevalence rates. Gambling is often a factor that contributes to an individual becoming homeless, but is also an important factor in the maintenance of the cycle of homelessness. Although the relationship between gambling and homelessness is complex, at the very least, it would be beneficial for homeless services to ask about gambling in any needs assessment and be informed and equipped to signpost (at least) to appropriate support services [67•]. Furthermore, although the existence of a problem has been established, there is still a lot we do not know. Evidence suggests that each individual has their own story, their own pathway littered with a plethora of economic, social, psychological, physical and mental health support needs; as such, it is unlikely that a one size fits all ‘responsible gambling’ approach would be successful, rather a person-centred, needs-focussed approach is likely to be more beneficial. Within the homeless population, different gamblers gamble on different forms for different reasons—but whilst the promise of a life changing win remains, so will the allure of gambling, despite the lived experience of the severe negative consequences.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Rose IN. Gambling and the law®: an introduction to the law of internet gambling. UNLV Gaming Res Rev J. 2006;10(1):1.

Schwartz DG. Roll the bones: the history of gambling.

Newall PW. Behavioral complexity of British gambling advertising. Addict Res Theory. 2017;25(6):505–11.

Lopez-Gonzalez H, Griffiths MD. “Cashing out” in sports betting: implications for problem gambling and regulation. Gaming Law Review. 2017;21(4):323–6.

Pitt H, Thomas SL, Bestman A, Stoneham M, Daube M. “It’s just everywhere!” children and parents discuss the marketing of sports wagering in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2016;40(5):480–6.

Thomas S, Pitt H, Bestman A, Randle M, Daube M, Pettigrew S. Child and parent recall of gambling sponsorship in Australian sport. Victoria: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation; 2016. p. 1.

• Cowlishaw S, Kessler D. Problem gambling in the UK: implications for health, psychosocial adjustment and health care utilization. Eur Addict Res. 2016;22(2):90–8 This paper provides an excellent foundation for understanding the impacts of disordered gambling in the UK.

Ronzitti S, Soldini E, Smith N, Potenza MN, Clerici M, Bowden-Jones H. Current suicidal ideation in treatment-seeking individuals in the United Kingdom with gambling problems. Addict Behav. 2017;74:33–40.

Welte J, Barnes G, Wieczorek W, Tidwell MC, Parker J. Alcohol and gambling pathology among US adults: prevalence, demographic patterns and comorbidity. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62(5):706–12.

Petry NM. Gambling and substance use disorders: current status and future directions. Am J Addict. 2007;16(1):1–9.

Battersby M, Tolchard B, Scurrah M, Thomas L. Suicide ideation and behaviour in people with pathological gambling attending a treatment service. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2006;4(3):233–46.

Roberts A, Landon J, Sharman S, Hakes J, Suomi A, Cowlishaw S. Gambling and physical intimate partner violence: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions (NESARC). Am J Addict. 2018;27(1):7–14.

Bramley G, Fitzpatrick S. Homelessness in the UK: who is most at risk? Hous Stud. 2018;33(1):96–116.

Shelter ‘Reaching Out’ http://england.shelter.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/66418/1385_Reaching_Out_report_FIN_Lo.pdf downloaded 5th September 2017 (2017).

Lepage C, Ladouceur R, Jacques C. Prevalence of problem gambling among community service users. Community Ment Health J. 2000 Dec 1;36(6):597–601.

Ladouceur R, Jacques C, Ferland F, Giroux I. Prevalence of problem gambling: a replication study 7 years later. Can J Psychiatr. 1999;44(8):802–4.

• Shaffer HJ, Freed CR, Healea D. Gambling disorders among homeless persons with substance use disorders seeking treatment at a community center. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(9):1112–7. This study provides an important international measure of gambling in the homeless population, from the USA–7.

Shaffer HJ, Hall MN, Vander Bilt J. Estimating the prevalence of disordered gambling behavior in the United States and Canada: a research synthesis. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1369–76.

Nower L, Eyrich-Garg KM, Pollio DE, North CS. Problem gambling and homelessness: results from an epidemiologic study. J Gambl Stud. 2015;31(2):533–45.

• Matheson FI, Devotta K, Wendaferew A, Pedersen C. Prevalence of gambling problems among the clients of a Toronto homeless shelter. J Gambl Stud. 2014;30(2):537–46. This study provides an important international measure of gambling in the homeless population, from Canada–46.

Cox BJ, Yu N, Afifi TO, Ladouceur R. A national survey of gambling problems in Canada. Can J Psychiatr. 2005;50(4):213–7.

• Sharman S, Dreyer J, Aitken M, Clark L, Bowden-Jones H. Rates of problematic gambling in a British homeless sample: a preliminary study. J Gambl Stud. 2015;31(2):525–32 This study provided the first estimate of disordered gambling prevalence in the UK, and is also the study with largest reported sample specifically to identify disordered gambling prevalence in the homeless.

Wardle, H., Moody, A., Spence, S., Orford, J., Volberg, R., Jotangia, D., et al. British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2010. London (UK): National Centre for Social Research. 2011.

• Sharman S, Dreyer J, Clark L, Bowden-Jones H. Down and out in London: addictive behaviors in homelessness. J Behav Addict. 2016;5(2):318–24 This study provides a recent estimate of gambling disorder prevalence in a homeless sample, seeks to understand the direction of the relationship, and provides data relating to the provision and utilisation of gambling support services.

Lesieur HR, Blume SB. The south oaks gambling screen (SOGS): a new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. Am J Psychiatr. 1987;144(9).

Shaffer HJ, LaBrie R, Scanlan KM, Cummings TN. Pathological gambling among adolescents: Massachusetts gambling screen (MAGS). J Gambl Stud. 1994;10(4):339–62.

Wickwire EM Jr, Burke RS, Brown SA, Parker JD, May RK. Psychometric evaluation of the national opinion research center DSM-IV screen for gambling problems (NODS). Am J Addict. 2008;17(5):392–5.

Toce-Gerstein M, Gerstein DR, Volberg RA. The NODS–CLiP: a rapid screen for adult pathological and problem gambling. J Gambl Stud. 2009;25(4):541–55.

Ferris J, Wynne H. The Canadian problem gambling index. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Canadian Centre on Subst Abus 2001.

Pluck G, Nakakarumai M, Sato Y. Homelessness and cognitive impairment: an exploratory study in Tokyo, Japan. East Asian Arch Psychiatr. 2015;25(3):122–7.

• Thorley C, Stirling A, Huynh E. Cards on the table: the cost to government associated with people who are problem gamblers in Britain. IPPR Report. 2016. This paper provides an excellent estimation of the financial cost of gambling to the UK government across a range of different areas.

Rose A, Maciver C and Davies B. Nowhere fast: the journey in and out of unsupported temporary accommodation, IPPR. (2016) http://www.ippr.org/publications/ nowhere-fast-the-journey-in-and-out-of-unsupported-temporary-accommodation. Accessed 10th Dec 2018

Gattis MN, Cunningham-Williams RM. Housing stability and problem gambling: is there a relationship? J Soc Serv Res. 2011;37(5):490–9.

Edens EL, Rosenheck RA. Rates and correlates of pathological gambling among VA mental health service users. J Gambl Stud. 2012;28(1):1–1.

Moghaddam JF, Yoon G, Campos MD, Fong TW. Social and behavioral problems among five gambling severity groups. Psychiatry Res. 2015;230(2):143–9.

Crane M, Byrne K, Fu R, Lipmann B, Mirabelli F, Rota-Bartelink A, et al. The causes of homelessness in later life: findings from a 3-nation study. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60(3):S152–9.

Lipmann B, Mirabelli F, Rota-Bartelink A. Homelessness among older people: a comparative study in three countries of prevention and alleviation. Melbourne: Wintringham; 2004.

van Laere IR, de Wit MA, Klazinga NS. Pathways into homelessness: recently homeless adults problems and service use before and after becoming homeless in Amsterdam. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):3.

Roberts A, Sharman S, Coid J, Murphy R, Bowden-Jones H, Cowlishaw S, et al. Gambling and negative life events in a nationally representative sample of UK men. Addict Behav. 2017;75:95–102.

Nielssen OB, Stone W, Jones NM, Challis S, Nielssen A, Elliott G, et al. Characteristics of people attending psychiatric clinics in inner Sydney homeless hostels. Med J Aust. 2018;208(4):169–73.

Cowlishaw S, Merkouris S, Chapman A, Radermacher H. Pathological and problem gambling in substance use treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Subst Abus Treat. 2014;46(2):98–105.

Petry NM, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:564–74.

Neale J. Homelessness amongst drug users: a double jeopardy explored. Int J Drug Policy. 2001;12(4):353–69.

Shelton K, Taylor P, Bonner A, van den Bree M. Risk factors for homelessness: evidence from a population-based study. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):465–72.

Michalczuk R, Bowden-Jones H, Verdejo-Garcia A, Clark L. Impulsivity and cognitive distortions in pathological gamblers attending the UK National Problem Gambling Clinic: a preliminary report. Psychol Med. 2011;41(12):2625–35.

De Wit H. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: a review of underlying processes. Addict Biol. 2009;14(1):22–31.

Marczinski CA, Abroms BD, Van Selst M, Fillmore MT. Alcohol-induced impairment of behavioral control: differential effects on engaging vs. disengaging responses. Psychopharmacology. 2005;182(3):452–9.

Sher KJ, Trull TJ. Personality and disinhibitory psychopathology: alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994;103(1):92–102.

O'Callaghan B, Dominian L, Evans A, Dix J, Smith R, Williams P, Zimmeck M. Study of homeless applicants. HM Stationery Office; 1996.

• Haushofer J, Fehr E. On the psychology of poverty. Science. 2014;344(6186):862–7 Paper provides a important foundation and fascinating perspective on the how living in and experiencing poverty can influence human cognition and behaviour.

Kemp PA, Lynch E, Mackay D. Structural trends and homelessness: a quantitative analysis. Edinburgh: Stationery Office; 2001.

Breen HM. Risk and protective factors associated with gambling consequences for indigenous Australians in North Queensland. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2012;10(2):258–72.

Orford J. Low income and vulnerability for gambling problems. Addiction. 2004;99(10):1356.

Rintoul AC, Livingstone C, Mellor AP, Jolley D. Modelling vulnerability to gambling related harm: how disadvantage predicts gambling losses. Addict Res Theory. 2013;21(4):329–38.

Grun L, McKeigue P. Prevalence of excessive gambling before and after introduction of a national lottery in the United Kingdom: another example of the single distribution theory. Addiction. 2000;95(6):959–66.

Livingstone C. The social economy of poker machine gambling in Victoria. Int Gambl Stud. 2001;1;1(1):46–65.

Wardle H, Keily R, Astbury G, Reith G. ‘Risky places?’: Mapping gambling machine density and socio-economic deprivation. J Gambl Stud. 2014;30(1):201–12.

Clotfelter CT, Cook PJ. Selling hope: state lotteries in America. Harvard University Press. 1991.

Slutske WS, Deutsch AR, Statham DJ, Martin NG. Local area disadvantage and gambling involvement and disorder: evidence for gene-environment correlation and interaction. J Abnorm Psychol. 2015;124(3):606–22.

Dyall L. Gambling, social disorganisation and deprivation. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2007;5(4):320–30.

Schissel B. Betting against youth: the effects of socioeconomic marginality on gambling among young people. Youth Soc. 2001;32(4):473–91.

van der Maas M. Problem gambling, anxiety and poverty: an examination of the relationship between poor mental health and gambling problems across socio-economic status. Int Gambl Stud. 2016;16(2):281–95.

Griskevicius V, Tybur JM, Delton AW, Robertson TE. The influence of mortality and socioeconomic status on risk and delayed rewards: a life history theory approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;100(6):1015–26.

Nyman JA, Dowd BE, Hakes JK, Winters KC, King S. Work and non-pathological gambling. J Gambl Stud. 2013;29(1):61–81.

• Lopes LL. Between hope and fear: the psychology of risk. In: Advances in experimental social psychology 1987 Jan 1 (Vol. 20, pp. 255–295). Academic Press. The article is important as it introduces the concept of the psychoeconomics of gambling in relation to homelessness.

Cooter R, Ulen T. Law and economics. (6th ed.). Berkeley Law Books. Berkeley: Addison-Wesley; 2016.

• Sharman S, D’Ardenne, J. Gambling and homelessness: developing an information sheet, screening tool and resource sheet. London: GambleAware, 2018. This study utilises a qualitative approach to understand the appeal of gambling within a homeless sample, and has developed a range of tools to assist homelessness practitioners in the identification and provision of support for homeless gamblers.

• Williams RJ, Volberg RA, Stevens RM. The population prevalence of problem gambling: Methodological influences, standardized rates, jurisdictional differences, and worldwide trends. Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre; 2012 May 8. This paper is important when considering prevalence of gambling problems in specific countries, and populations as it highlights some of the methodological flaws and difficulties faced by researchers.

Holdsworth L, Tiyce M. Exploring the hidden nature of gambling problems among people who are homeless. Aust Soc Work. 2012;65(4):474–89.

Funding

Dr. Sharman is currently funded by an Academic Fellowship from the Society for the Study of Addiction. Some of Dr. Sharman’s previous work referenced in this review [67•] was funded by GambleAware. GambleAware is an independent charity tasked to fund research, education and treatment services to help reduce gambling-related harms in Great Britain, funded via voluntary donations from the gambling industry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Sharman declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies reporting new data with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. All studies referenced authored by the author of this article were conducted after receiving appropriate ethical approval.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Gambling

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sharman, S. Gambling and Homelessness: Prevalence and Pathways. Curr Addict Rep 6, 57–64 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-00242-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-00242-6