Abstract

The diagnosis of branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (BD-IPMNs) has been dramatically increased. BD-IPMNs are frequently discovered as incidental findings in asymptomatic individuals, mainly in elderly patients. An accurate evaluation of BD-IPMNs with high-resolution imaging techniques and endoscopic ultrasound is necessary. Patients with high-risk stigmata (HRS, obstructive jaundice, enhanced solid component) should undergo resection. Patients with worrisome features (WF, cyst size ≥3 cm, thickened enhanced cyst walls, non-enhanced mural nodules, and clinical acute pancreatitis) may undergo either a strict surveillance based on patients’ characteristics (age, comorbidities) or surgical resection. Non-operative management is indicated for BD-IPMNs without HRS and WF. Patients with BD-IPMN who do not undergo resection may develop malignant change over time as well as IPMN-distinct pancreatic cancer. However, non-operative management of BD-IPMNs lacking WF and HRS is safe and the risk of malignant degeneration seems relatively low. The optimal surveillance protocol is currently unclear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The diagnosis of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas has dramatically increased in the last two decades. Currently, the incidence of pancreatic cysts in the US population is estimated to be between 3 and 15 % [1, 2]. A significant proportion of these cysts are actually branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (BD-IPMNs), that are diagnosed in most cases as incidental findings in asymptomatic individuals. BD-IPMNs occur more frequently during the sixth or seventh decades of life with a slight prevalence for male sex [3, 4]. They can arise in any portion of the pancreatic gland, but they are found more commonly in the pancreatic head or in the uncinated process. Of note, BD-IPMNs are multifocal in about 30–40 % of cases, and involvement of the entire pancreatic gland is possible [1–4]. Several Authors have showed that BD-IPMNs are associated with lower rate of malignancy compared with main-duct and combined-IPMNs [5–7]. Most BD-IPMNs are gastric-type IPMNs. This type usually shows low-grade atypia and rarely exhibits malignant transformation. As a matter of fact, BD-IPMNs are associated with malignancy in about 25 % of cases in surgical series, and with invasive carcinoma in 15 % [5–7]. However, these data reflect a highly selected population of patients who underwent surgery. When considering the entire cohort of patients with a clinico-radiologic diagnosis of BD-IPMNs, only a few require surgical treatment, and the overall risk of malignancy is less than 5 % [8].

Several guidelines have been recently published for the management of pancreatic cysts, including BD-IPMNs [5–7, 9]. In this review, we will analyze indications for both surgical resection and non-operative management based on current evidence and expert guidelines.

Diagnostic assessment and indications for surgery

Symptoms

Surgical resection should be considered in all symptomatic patients with BD-IPMNs for amelioration of symptoms and owing to the higher risk of malignancy in this setting [5–7]. However, symptoms should be carefully evaluated to discriminate between “major symptoms” such as jaundice, and aspecific symptoms such as vague abdominal pain that can be unrelated to the presence of the BD-IPMNs. Jaundice is frequently associated with the presence of malignant IPMNs [5–7, 9, 10]. Other symptoms may include “pancreatic pain”, new onset or worsening diabetes, or steatorrhea and weight loss due to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Acute pancreatitis has been linked to younger age of onset and to higher risk of malignancy in main-duct IPMNs [11], but it may be the presenting symptom also for BD-IPMN due to main pancreatic duct (MPD) occlusion by mucin plugs [12]. However, in the setting of small BD-IPMNs without signs of risk, other possible causes of acute pancreatitis (i.e., biliary stones) should be ruled out before planning a pancreatic resection.

Imaging features

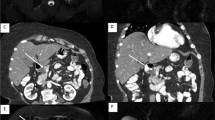

All pancreatic cysts greater than 10 mm should undergo pancreatic protocol computed tomography (CT) or gadolinium-enhanced MRI with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) to characterize the lesion [5]. MRI is the procedure of choice for evaluating a pancreatic cyst, including BD-IPMNs, based on its superior contrast resolution that facilitates recognition of nodules, thickened walls and eventually duct communications [5–7]. In this light, BD-IPMNs are defined as pancreatic cyst(s) clearly communicating with a non-dilated MPD (MPD < 5 mm). Based on international guidelines, all IPMNs with a MPD > 5 mm should be classified as mixed/main-duct IPMNs. However, a mild MPD dilatation (<9 mm) can be the result of mucin filling into MPD from a branch-duct lesion [12]. Therefore, MPD dilatation <9 mm should be further evaluated with endoscopic ultrasound.

Different radiological parameters have been definitely associated with the presence of malignancy in BD-IPMNs [5, 13]:

-

enhancing solid component (vascularized mural nodule);

-

enhancing cyst walls;

When CT or MRI clearly shows the presence of these radiological parameters, surgery should be considered. On the contrary, non-enhancing solid components, thickened cyst walls or cyst size >30 mm require further diagnostic work-up with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) [5].

Although a systematic review and meta-analysis identified cyst size >30 mm as a risk factor for malignancy [14], several studies showed that the exclusive presence of cyst size >30 mm in the absence of other malignancy-related features (i.e., vascularized nodules, jaundice) is not strictly indicative of a malignant degeneration of the IPMN [4–7]. The threshold of 3 cm in diameter does not represent alone a strict indication for surgery anymore. In this setting, International Consensus guidelines suggest very strict surveillance or surgery for BD-IPMNs > 30 mm depending on patients’ age, preference and comorbidities, and a similar policy is also adopted by Italian guidelines; on the other hand, European guidelines are more conservative and recommend surgery only for BD-IPMNs > 40 mm unless other risk factors are present. However, any BD-IPMN > 30 mm requires further evaluation with EUS and FNA [5–7, 9].

Endoscopic ultrasound features

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) should be considered in the diagnostic work-up of patients with BD-IPMNs when there are concerning features at imaging or after clinical evaluation. EUS is a highly sensitive imaging modality for morphologic evaluation of BD-IPMNs and with interventional capabilities, including aspiration of cyst fluid and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) for cytology [5–7, 9]. In patients with non-enhancing solid components, EUS is of paramount importance to make a differential diagnosis with mucin and mucin plugs. In fact mucin can move with change in patient position, may be dislodged on cyst lavage and does not have Doppler flow. Features of true tumor nodule include lack of mobility, presence of Doppler flow or evidence of vascularization during EUS with contrast medium, and these clearly represent indication for surgical resection. Moreover, in patients with mild MPD dilatation (<9 mm), EUS may show thickened walls, intraductal mucin or mural nodules. These findings are suggestive of main-duct involvement by the tumor (main-duct/combined-IPMNs), another indication for surgery [5].

EUS-FNA is a safe and accurate technique to obtain cytological samples from any solid component but it can also be used to aspirate fluid from cystic lesions. Cyst fluid cytology is an accurate test for the diagnosis of a malignant BD-IPMNs but the sensitivity of cytology may be lowered by the scant cellularity of cyst fluid [15]. When cytology shows malignant cells but also cells with moderate to severe atypia, surgery must be considered. Furthermore, cyst fluid analysis includes also the evaluation of amylase content and tumor markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). Of note, cyst fluid CEA levels help only to differentiate serous from mucinous cystic lesions, while it has no role in predicting the degree of dysplasia or the presence of malignancy [15].

Serum CA 19.9 level

Serum carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 may be elevated in the setting of malignant IPMNs with a sensitivity ranging from 79 to 100 % [6]. However, normal CA 19.9 levels does not exclude the presence of a malignancy (sensitivity 37–80 %). Serum CA19.9 determination provides additional information within the diagnostic work-up, but an elevated serum CA 19.9 level in the absence of other clinico-radiological indications for resection should represent an indication for further work-up and/or strict non-operative follow-up.

Family history of pancreatic cancer and familial pancreatic cancer

The presence of a family history of pancreatic carcinoma (presence of one relative with pancreatic cancer) does not seem to increase the risk of malignant transformation of BD-IPMNs [16].

On the other hand it is more complex for the management of patients with BD-IPMNs and with conditions at higher risk of pancreatic cancer including Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, hereditary pancreatitis, or patients with known gene defect such as CDKN2A, BRCA1/BRCA2, PALPB2 mutations or with familial pancreatic cancer (FPC). FPC describes families with at least two first-degree relatives with confirmed exocrine pancreatic cancer that do not fulfill the criteria of other inherited tumor syndromes with increased risks of pancreatic cancer [17]. The appropriate management of asymptomatic BD-IPMNs without concerning features at imaging/EUS in these patients is unknown. Of note, a recent study [18] showed that in the setting of FPC, the presence of multiple small BD-IPMNs at preoperative imaging corresponded to gastric-type benign BD-IPMNs after pancreatectomy, and these IPMNs were frequently associated with multifocal moderate to high-grade PanIN lesions distinct from the IPMNs elsewhere in the pancreas. Unfortunately these PanIN lesions could not be visualized on preoperative imaging, including both MRI/MRCP or EUS.

Worrisome features and high-risk stigmata

The 2012 updated version of the International Association of Pancreatology guidelines for IPMNs well summarized the indications for surgical resection of BD-IPMN [5]. These guidelines introduced two categories of risk factors for malignancy, namely “worrisome features” and “high-risk stigmata”.

High-risk stigmata (HRS) include:

-

Jaundice;

-

MPD ≥ 10 mm;

-

enhancing nodules or solid component;

-

cytology positive for high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma.

Worrisome features (WF) include:

-

cyst size >30 mm;

-

MPD size of 5–9 mm;

-

pancreatitis;

-

minor symptoms;

-

non-enhancing nodules;

-

atypical cells at cytology.

These guidelines emphasized that the presence of HRS warrants immediate surgical resection, while BD-IPMNs with WF should be further evaluated by endoscopic ultrasound, and depending on the results of EUS + FNA, patients may undergo surgery or they may be followed very closely [5]. Since BD-IPMNs are frequently discovered incidentally in elderly patients with associated comorbidities, international guidelines suggest to limit surgery to “good surgical candidates” and to take into account life expectancy and patients’ conditions to plan the most appropriate management. A recent study [19] evaluated mid-term outcomes (median follow-up 51 months) in a cohort of 281 patients with IPMNs with WF and HRS who did not undergo surgery because of advanced age or comorbidities. Of 281 patients identified, 159 (57 %) had BD-IPMNs and 122 (43 %) had MD-IPMNs, 50 (18 %) had HRS and 231 (82 %) had WF. The 5-year overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) for the entire cohort were 81 and 89.9 %. Compared to main-duct/combined-IPMNs, BD-IPMNs had significantly better 5-year OS (86 versus 74.1 %, P = 0.002) and DSS (97 versus 81.2 %, P < 0.0001). Remarkably, patients with WF had better 5-year DSS compared to those with HRS (96.2 versus 60.2 %, P < 0.0001). Interestingly, no correlation among cyst size >30 mm, cyst size >50 mm or increase of BD size during follow-up and survival was found in this study [19]. These data underline that while patients with HRS should be considered for surgery, the clinical course of patients with WF seems more indolent, and therefore, non-operative management with close follow-up may be appropriate, particularly in those with major comorbidities and/or advanced age.

Surgical treatment

When an indication for surgical resection is present, the type of resection is planned based on the presence of HRS, WF, and by the site and extension of the IPMN.

Type of resection

When preoperative imaging identified BD-IPMNs with a significant risk of malignancy (i.e., presence of HRS), pancreaticoduodenectomy, left pancreatectomy with splenectomy or total pancreatectomy should be considered with standard lymphadenectomy [5–7, 9]. During partial pancreatectomy the intraoperative histological examination of the pancreatic margin must always be performed. IAP guidelines suggest that when low-grade dysplasia is present at the resection margin, no further resection is required because the risk of progression to cancer or local recurrence is minimal; instead, moderate- or high-grade dysplasia as well as invasive carcinoma at the FS requires an additional resection, up to a total pancreatectomy [5].

As previously mentioned, BD-IPMNs are multifocal in most cases, and the entire gland may be involved. In this setting there are different surgical options. Partial pancreatectomy is usually feasible with the aim of resecting the dominant cyst with HRS or WF, leaving behind the remaining BD-IPMN(s) in the pancreatic remnant. This practice appropriately balances the detrimental long-term effects of both endocrine and exocrine insufficiency with an acceptable reduction in risk of malignancy. Other strategies may include partial pancreatectomy with enucleation of the other larger cyst(s) or middle-preserving pancreatectomy for multifocal BD-IPMNs in the head and tail of the gland, namely a pancreaticoduodenectomy associated with tail resection, leaving the pancreatic body of the pancreas.

Middle pancreatectomy and enucleation have been also proposed for the treatment of BD-IPMNs [20]. These procedures preserve pancreatic parenchyma and reduce the risk of postoperative endocrine and exocrine insufficiency. These procedures should be considered in the absence of HRS. The main indication for middle pancreatectomy is a large cyst without abnormal findings at preoperative cytology and without solid components, located in the pancreatic neck. For reconstruction either antecolic, end-to-side, mucosa-to-mucosa, Roux-en-Y pancreaticojejunostomy or a pancreatico-gastrostomy can be made. The role of enucleation for BD-IPMNs is unclear. It has been showed that enucleation can be performed safely, but data regarding long-term oncological outcomes of this procedure are scant. A multi-institutional international series by Turrini et al. [21] evaluated 107 patients undergoing pancreatic surgery for BD-IPMN of the pancreatic head/uncinated—seven undergoing enucleation and 100 undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. They found that the enucleation group had a significantly shorter operative time and lower blood loss and a non-statistically significantly higher fistula rate. However, considering oncological principles, enucleation of BD-IPMN is not an adequate resection [22]. In fact the main limitation of this procedure is the lack of an appropriate examination of the connection between the cyst and the MPD to exclude pathologically the presence of a mixed IPMN.

Follow-up after surgical resection

Several Authors showed that a resection of a benign BD-IPMN reduces but does not eliminate the risk of developing pancreatic malignancy. Moreover, after resection of a benign IPMN, the development of subsequent BD-IPMN is reported in up to 20 % of patients, and pancreatic cancer in the pancreatic remnant has been also described [5–7, 9, 23]. Some Authors found that the finding of high-grade dysplasia in the primary lesion is a marker for relatively aggressive biology since this was found in all patients who subsequently developed a cancer [23, 24]. Based on these data, it is clear that patients who have undergone resection of BD-IPMN need lifetime follow-up. In general, patients with cysts in the remnant pancreas should be followed as per BD-IPMN protocol. Those without cysts can undergo surveillance yearly.

Non-operative management of BD-IPMNs

Current guidelines suggest that asymptomatic patients with BD-IPMNs lacking HRS and WF should undergo surveillance [5–7, 9]. As previously mentioned, also patients with BD-IPMNs with WF at imaging may undergo surveillance based on patients’ characteristics (age, comorbidities and patients’ preference) and after a EUS examination with FNA that confirmed the absence of HRS and/or malignant/atypical cells at cytology [5, 19].

Different guidelines proposed different mode of follow-up and different follow-up timing. It is important to underline that current guidelines are “expert or consensus” guidelines rather than evidence-based guidelines. Existing guidelines provide adequate guidance, at least with the present knowledge, for the management of cystic pancreatic lesions including BD-IPMNs; however, a recent evaluation of the available guidelines by experts in the field showed that not any one was satisfactory to all aspects related to the management of pancreatic cystic neoplasms [25]. An update of the existing guidelines should be considered if and when more evidence-based data are available. In fact the level of evidence for most of the issues included in the guidelines is unfortunately low, and this must be taken into account. In general, MRI/MRCP is the preferred follow-up modality since this is non-invasive and it does not expose the patient to radiation; EUS is considered as well in the guidelines, especially for the follow-up of patients with WF.

The goal of the surveillance program in patients with BD-IPMNs is twofold. The main aim is to identify significant changes in BD-IPMNs (i.e., development of HRS) that may be associated with malignancy to perform surgery in this subset of patients. The second aim is to identify IPMN-distinct pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma during the follow-up of patients with “low-risk” BD-IPMNs.

Risk of pancreatic cancer during follow-up of BD-IPMNs

The incidence of PDAC development in patients with IPMNs has been estimated in a few prospective and several retrospective cohort studies. The rate of IPMN-distinct adenocarcinoma during the surveillance of BD-IPMNs is reported between 1.4 and 11.2 %, while other authors suggested an incidence greater than expected in the general population by 10.7- to 26-fold [5, 26–28]. In view of this prevalence of PDAC, careful inspection of the entire pancreatic gland is necessary for early detection of PDAC in patients with branch-duct IPMNs; worsening diabetes mellitus and an abnormal serum CA 19-9 level have been associated with the evidence of IPMN-distinct PDAC.

Timing of follow-up

The timing of follow-up is determined by the presence/absence of WF, and by the size of the dominant cyst. IAP guidelines [5] suggest a very close surveillance for BD-IPMNs with WF, alternating MRI with EUS every 3–6 months. All patients with cysts of <3 cm in size without WF should undergo surveillance according the size stratification: (1) MRI after 2–3 years for cysts <10 mm; (2) MRI yearly for two consecutive years for cysts ranging between 10 and 20 mm, then lengthen interval if no change; (3) MRI/EUS every 6/12 months for cysts ranging between 20 and 30 mm. Similar follow-up timing is also suggested by the Italian guidelines [6]. Of note, these latter guidelines suggest to include transabdominal ultrasound (US) for the surveillance of small BD-IPMNs that can be identified with this technique, although with US the proper evaluation of the development of small solid component can be difficult. On the other hand European guidelines [9] suggest regardless of cyst size MRI or EUS every 6 months for the first year and yearly thereafter for the first 5 years, with 6-month follow-up evaluation after the fifth year. This is an interesting concept, assuming that the risk of malignant degeneration of the IPMN may increase after time. In contrast with this view, recently published guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) [7] suggests that patients with pancreatic cysts <3 cm without a solid component, including BD-IPMNs, undergo MRI for surveillance in 1 year and then every 2 years for a total of 5 years. Of note, AGA guidelines propose to discontinue surveillance after 5 years if no changes occur, while the remaining guidelines recommend lifetime follow-up. Considering that the natural history of IPMNs is still unknown and that IPMN-distinct PDAC may arise in these patients, we strongly believe that surveillance should not be discontinued.

Risk of malignancy and mortality during follow-up

Clarification of the incidence of malignant BD-IPMNs and/or of IPMN-distinct PDAC during the follow-up of BD-IPMNs that were managed non operatively is essential in evaluating the value of surveillance in BD-IPMNs without malignancy-related features. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 20 studies including 2177 patients showed favorable results in this setting [29]. Mean follow-up ranged from 29.3 to 76.7 months and median follow-up from 21 to 97 months. BD-IPMN progression during follow-up was reported in 614/2177 patients (28 %), and it consisted mainly in increase in size (n = 465; 21.3 %) while the development of nodules was found in 8.5 %. Overall, 82 patients out of 2177 developed a pancreatic malignancy (3.7 %), with a rate of pancreatic malignancy between 0 and 10 %. Specifically, rate of development of malignant BD-IPMN and of IPMN-distinct PDAC during follow-up were 2.4 % (53/2177 patients) and 1.3 % (29/2177 patients), respectively. Only 12 studies out of the 20 studies reported data regarding the incidence rate of death due to pancreatic malignancies, and this rate was 0.9 % (9/962 patients), ranging from 0 to 4.5 %. Based on these results, the risks of malignant degeneration and eventual mortality in patients with BD-IPMNs undergoing surveillance are comparable to the risk of postoperative mortality following pancreatic resection, suggesting that non-operative management of “low-risk” BD-IPMNs, as has been suggested in the International Consensus Guidelines, is safe.

Conclusions

The management of BD-IPMNs still remains challenging. Current guidelines seem to be safe to identify patients at risk of being or harboring a malignancy. However, these guidelines are still imperfect as most patients with BD-IPMNs who undergo resection have benign lesions. The non-operative management of BD-IPMNs lacking WF and HRS is safe and the risk of malignant degeneration seems relatively low, and at least it is comparable with the risk of postoperative mortality after pancreatic surgery. More data are necessary to evaluate the long-term outcome (>5 year) of surveillance program in this setting. It is likely that in the future the identification of molecular markers will help to identify those patients at risk of progression to personalize the management of these lesions [30, 31].

References

Canto MI, Hruban RH, Fishman EK et al (2012) Frequent detection of pancreatic lesions in asymptomatic high-risk individuals. Gastroenterology 142:796–804

Crippa S, Fernández-Del Castillo C, Salvia R et al (2010) Mucin-producing neoplasms of the pancreas: an analysis of distinguishing clinical and epidemiologic characteristics. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 8:213–219

Rodriguez JR, Salvia R, Crippa S et al (2007) Branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: observations in 145 patients who underwent resection. Gastroenterology 133:72–79

Sahora K, Mino-Kenudson M, Brugge W et al (2013) Branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: does cyst size change the tip of the scale? A critical analysis of the revised international consensus guidelines in a large single-institutional series. Ann Surg 258:466–475

Tanaka M, Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay V, International Association of Pancreatology et al (2012) International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology 12:183–197

Buscarini E, Pezzilli R, Cannizzaro R et al (2014) Italian consensus guidelines for the diagnostic work-up and follow-up of cystic pancreatic neoplasms. Dig Liver Dis 46:479–493

Vege SS, Ziring B, Jain R, Moayyedi P, Clinical Guidelines Committee, American Gastroenterology Association (2015) American gastroenterological association institute guideline on the diagnosis and management of asymptomatic neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology 148:819–822

Marchegiani G, Fernández-del Castillo C (2014) Is it safe to follow side branch IPMNs? Adv Surg 48:13–25

Del Chiaro M, Verbeke C, Salvia R et al (2013) European experts consensus statement on cystic tumours of the pancreas. Dig Liver Dis 45:703–711

Aso T, Ohtsuka T, Matsunaga T et al (2014) “High-Risk Stigmata” of the 2012 international consensus guidelines correlate with the malignant grade of branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreas 43:1239–1243

Morales-Oyarvide V, Mino-Kenudson M, Ferrone CR et al (2015) Acute pancreatitis in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: a common predictor of malignant intestinal subtype. Surgery 158:1219–1225

Crippa S, Pergolini I, Rubini C et al (2016) Risk of misdiagnosis and overtreatment in patients with main pancreatic duct dilatation and suspected combined/main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Surgery 159:1041–1049

Kim KW, Park SH, Pyo J et al (2014) Imaging features to distinguish malignant and benign branch-duct type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg 259:72–81

Anand N, Sampath K, Wu BU (2013) Cyst features and risk of malignancy in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 11:913–921

Maker AV, Carrara S, Jamieson NB et al (2015) Cyst fluid biomarkers for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: a critical review from the international expert meeting on pancreatic branch-duct-intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. J Am Coll Surg 220:243–253

Mandai K, Uno K, Yasuda K (2014) Does a family history of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and cyst size influence the follow-up strategy for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas? Pancreas 43:917–921

Bartsch DK, Gress TM, Langer P (2012) Familial pancreatic cancer—current knowledge. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 9:445–453

Bartsch DK, Dietzel K, Bargello M et al (2013) Multiple small “imaging” branch-duct type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) in familial pancreatic cancer: indicator for concomitant high grade pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia? Fam Cancer 12:89–96

Crippa S, Bassi C, Salvia R et al (2016) Low progression of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms with worrisome features and high-risk stigmata undergoing non-operative management: a mid-term follow-up analysis. Gut. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310162

Crippa S, Bassi C, Warshaw AL et al (2007) Middle pancreatectomy: indications, short- and long-term operative outcomes. Ann Surg 246:69–76

Turrini O, Schmidt CM, Pitt HA et al (2011) Side-branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreatic head/uncinate: resection or enucleation? HPB (Oxford) 13:126–131

Crippa S, Bassi C, Salvia R, Falconi M, Butturini G, Pederzoli P (2007) Enucleation of pancreatic neoplasms. Br J Surg 94:1254–1259

He J, Cameron JL, Ahuja N et al (2013) Is it necessary to follow patients after resection of a benign pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm? J Am Coll Surg 216:657–665

Rezaee N, Barbon C, Zaki A et al (2016) Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) with high-grade dysplasia is a risk factor for the subsequent development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 18:236–246

Falconi M, Crippa S, Chari S et al (2015) Quality assessment of the guidelines on cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology 15:463–469

Uehara H, Nakaizumi A, Ishikawa O et al (2008) Development of ductal carcinoma of the pancreas during follow-up of branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Gut 57:1561–1565

Tanno S, Nakano Y, Sugiyama Y et al (2010) Incidence of synchronous and metachronous pancreatic carcinoma in 168 patients with branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Pancreatology 10:173–178

Sahora K, Crippa S, Zamboni G et al (2016) Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas with concurrent pancreatic and periampullary neoplasms. Eur J Surg Oncol 42:197–204

Crippa S, Capurso G, Cammà C, Delle Fave G, Castillo CF, Falconi M (2016) Risk of pancreatic malignancy and mortality in branch-duct IPMNs undergoing surveillance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis 48:473–479

Springer S, Wang Y, Dal Molin M et al (2015) A combination of molecular markers and clinical features improve the classification of pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology 149:1501–1510

Paini M, Crippa S, Partelli S et al (2014) Molecular pathology of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. World J Gastroenterol 20:10008–10023

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

No animals were involved in the study.

Informed consent

Informed written consent was taken from all the participants involved in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crippa, S., Piccioli, A., Salandini, M.C. et al. Treatment of branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: state of the art. Updates Surg 68, 265–271 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-016-0386-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-016-0386-8