Abstract

Customer product returns are a key challenge for online retailers. Previous research primarily focused on causes of returns and possible interventions to reduce customers’ product returns and concomitant costs for online retailers. However, little is known about the effect of product returns on key relational outcomes. Drawing on relationship marketing theory, we test a model that relates product returns to three relationship marketing outcomes—customer satisfaction, trust, and positive word-of-mouth. A field study based on online panel data from customers of eight large online retailers demonstrates that product returns negatively affect customer satisfaction with the retailer, customer trust, and word-of-mouth. The findings extend previous research by revealing that product returns can detrimentally affect relationships with customers. Implications for e-commerce research and management are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Online retailers have to deal with the challenge of product returns, which represent a major cost driver. Typical product return rates range from 10% to 30% for U.S. retailers depending on product category (Brohan 2013; Ibi research 2013). Large European online fashion retailers such as Zalando even report return rates of up to 50% (Müller 2013; Weverbergh 2013). Handling returned items that are in a saleable condition costs online retailers between $6 and $18 per item (The Economist 2013). It is not surprising then that e-commerce scholars and practitioners have focused attention on drivers of individual-level consumer product returns (e.g., Ram 2016; Walsh et al. 2016).

The pertinent literature has identified various consumer-related and firm-related drivers of consumer product returns. For example, Maity and Arnold (2013) report that the effort and the experience of consumers’ online product search affect their return rate. Others investigated dysfunctional and fraudulent consumer return behavior (e.g., Harris 2008; Wang et al. 2012). Studies dealing with firm-related drivers of consumer product returns found that online retailers’ reputation decreases returns (Walsh et al. 2016) whereas lenient return policies increase the probability of orders and returns as well as online retailers’ profit (Wood 2001; Zhou and Hinz 2015). The profit-boosting effect of returns, which on the surface appears counterintuitive, is explained by Petersen and Kumar (2009, p. 45) who state “that up to a threshold, increases in product return behavior increase future customer purchase behavior”. However, Shah et al. (2012) argue that this problem (i.e., excessive product returns) is particularly common for retailers with very liberal product return policies. Moreover, favorable online product reviews (Minnema et al. 2016) and re-stocking fees (Petersen and Anderson 2015) are shown to suppress returns. Bower and Maxham (2012) report that customers who had to pay for their returns spent significantly less subsequently than customers whose returns were free (75%–100% vs. 158%–457% of pre-return spending by the end of two years).

Although past research suggests that there is a direct link between consumer-related and firm-related drivers of consumer product returns and actual return behavior, there is scarce empirical research examining whether and to what extent consumers’ attitudes and behaviors are affected after products had been returned. An exception are studies using longitudinal data (e.g., Bower and Maxham 2012; Petersen and Kumar 2009). However, those studies focus on post-return spending behavior (i.e., behavior after the product is returned) and neglect psychological constructs which seem useful in understanding how returns may affect customer relationships with the online retailer. Taken together, no research has examined the effects of product returns on relational outcomes. This is an important oversight given that customer relationships are the “raison de etre of the firm” (Parvatiyar and Sheth 2000, p. 6).

This research gap invites research into consumer behavioral outcomes of product returns. We attempt to fill this gap in the literature by relating product returns to three relational outcomes widely considered as key relational constructs (e.g., Ahearne et al. 2005; Blut et al. 2014; Gummerus et al. 2012)—customer satisfaction, trust, and positive word-of-mouth. The proposed link between consumer product returns and their relationship with the retailer is important for both theoretical and managerial reasons. Theoretically, to gain a complete understanding of the impact of product returns on online retailers, scholars need to move beyond existing findings focused on drivers of returns to examine consumer-related behavioral outcomes of returns. Managerially, such research is valuable because product returns may undermine a retailer’s relationship marketing efforts, which refer “to all marketing activities directed toward establishing, developing, and maintaining successful relational exchanges” (Morgan and Hunt 1994, p. 22). Thus, product returns not only lead to higher handling costs and lower profitability but may also hamper the online retailer’s efforts to promote return business.

This research is organized as follows. First, we review the existing literature on product return consequences. Then, we propose a conceptual model that links customers’ product returns to key relationship marketing outcomes—customer satisfaction, trust, and positive word-of-mouth in relation to the online retailer. Specifically, we theorize that product returns are negatively related with all three relationship marketing outcomes. Next, we test this conceptual model using data from an online panel. Finally, we discuss implications for product return management and further research.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Literature review on return consequences

As mentioned earlier, product returns-related research largely focused on the drivers of product returns. In contrast, the present research aims to shed light on the consequences of product returns, that is, on attitudes and behaviors resulting from returns. Table 1 provides a comprehensive but not exhaustive summary of the pertinent literature and highlights the fact that only few studies examined the consequences of product returns in terms of subsequent customer behavior.

The existing literature has emphasized the impact of handling returns. Bower and Maxham (2012), using longitudinal field studies over four years, found that customers who had to pay for their returns spent subsequently less than customers who were not charged a return fee. Similarly, Griffis et al. (2012a) investigated the effect of return speed on the basis of real customer data reporting that return speed affects order frequency, number of items per order, and therefore the total value of the customer relationship. Ramanathan (2011) used aggregated rating data from 1070 websites to demonstrate that the ease of returns and refunds positively influence customer loyalty for low- and high-risk products. Mollenkopf et al. (2007) explored relationships between different aspects of return management systems (e.g., service recovery, site ease) and customer loyalty intentions. However, these studies did not investigate customer-related consequences of product returns, such as the impact of customers’ product return rate on behavioral or relational outcomes. Only Petersen and Kumar (2009) measured the impact of product returns on subsequent buying behavior. They found that returns positively affect the number of future purchases up to a threshold. However, their data contained not only Internet, but also catalog, telephone, and retail purchases. Thus, it remains unclear whether Internet returns actually increase loyalty in the form of subsequent purchases or whether they affect other relational outcomes.

Collectively, these studies outline the relevance of handling product returns in a customer friendly way and indicate effects on subsequent purchase behavior. Nevertheless, no study thus far has explored the relationship between costumers’ product returns and relationship marketing outcomes, such as customer satisfaction, trust, and positive word-of-mouth, even though relationship marketing outcomes are considered as very important for online retailers (Gao and Liu 2014; Gefen 2000; Kim et al., 2009a).

Relationship marketing and relational outcomes

Central to relationship marketing theory (e.g., Hennig-Thurau et al. 2002; Morgan and Hunt 1994) is the notion that customer-firm relationships should be mutually beneficial. Because relationships are critical to the success of the organization, Möller and Halinen (2000, p. 31) maintain that “buyer-seller relationships are the core issue in relationship marketing, and in the whole marketing discipline.” Service firms, especially retailers, invest in relationship marketing activities to positively affect customer relationship outcomes. The pertinent literature details various relationship outcomes, however, it is widely accepted that the following are among the key relationship outcomes: customer satisfaction, trust, and positive word-of-mouth (Gao and Liu 2014; Kim et al. 2009b; Sabiote and Román 2009; Walsh et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2011).

Customer satisfaction refers to the consumer’s response to the evaluation of the perceived discrepancy between prior expectations and the actual performance of a product or service (Day 1984). The customer’s general satisfaction with a retailer will be continually updated based on recent experiences with the retailer and the resulting level of satisfaction (Mollenkopf et al. 2007; Oliver 1997). Customers’ satisfaction with a relationship again leads to relationship commitment and loyalty (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2002; Morgan and Hunt 1994; Petersen and Kumar 2009). Ideally, customers feel such a level of satisfaction based on the retailer’s past performance that they will not consider other retailers that provide similar products and services (Dwyer et al. 1987). Therefore, customers’ satisfaction with an online retailer is a key driver for subsequent purchases (Kim et al. 2009a; Liao et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2011).

Satisfaction results from customers’ past experience with a retailer, whereas trust refers to customers’ confidence in the retailer’s future performance (Anderson and Narus 1990; Zhang et al. 2011). According to Moorman et al. (1992), trust is defined as the customer’s willingness to rely on a seller in whom one has confidence. Trust is also viewed as a benefit customers receive as a result of a long-term relationship with a retailer (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2002). This benefit leads to reduced anxiety and increased comfort in knowing what to expect (Gwinner et al. 1998), and thus encourages customers to continue the relationship. Trust is per se desirable for retailers, but it also positively affects relationship commitment and functional conflict as well as reduces customers’ decision-making uncertainties, acquiescence, and propensity to leave (Morgan and Hunt 1994). In the online context, trust is a key determinant for the retailer’s success (Kim and Benbasat 2006) as it directly leads to customers’ increased intentions to purchase (e.g., Gefen 2002; Kim et al. 2009a; Lim et al. 2006).

While trust and satisfaction are key for customer retention, positive word-of-mouth, on the other hand, is very helpful to attract new customers (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2002). Customer retention and attraction are both important for retailers’ long-term success. Hence, attracting new customers is key to successful relationship marketing activities (Berry 1983; Grönroos 1990; Morgan and Hunt 1994) and thus word-of-mouth is viewed as an important relational outcome in the marketing literature (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2002). Positive word-of-mouth refers to the communication between customers, concerning the evaluation of products or services, and involves “relating pleasant, vivid, or novel experiences; recommendations to others; and even conspicuous display” (Anderson 1998, p. 6). This positive communication between existing and potential customers helps to attract new customers for retailers (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2002).

The relevance of lasting and mutually beneficial relationships has also been noted for online retailers. (McNaughton et al. 2001, p. 532) argue that because online retailers face increasing customer demands, retailers face “issues in managing order fulfilment processes, billing and maintaining customer service levels in domestic markets and overseas. In this context, enhanced customer service skills are critical to deepen customer interactions and build long and profitable relationships.” In contrast to brick and mortar stores, online retailers just have a few virtual touch points with their customers, as online retailers’ communication with customers is predominantly based on website interaction. Online retailers often find it more difficult to create a lasting relationship with their customers since the parties are not in the same physical location and cannot rely on physical cues, such as proximity, handshakes, body signals, and the human senses in general (sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch; Laroche et al. 2005). Therefore, the effective fulfilment of online shopping orders has been identified as critical for shaping relational outcomes (Griffis et al. 2012b; Liao et al. 2010; Rao et al. 2011), implying that the handling of shopping returns might be crucial, too.

Apart from being logistically complex and expensive, product returns may be viewed by customers as an indication of the retailer’s ineptness. In other words, product returns may be conceptualized as service failures, which detrimentally affect relational outcomes (Chuang et al. 2012; Dai and Salam 2014; Hui et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2009b; Van Vaerenbergh et al. 2014). Because it is harder for online retailers compared to offline retailers to develop and nurture relationships with customers (Walsh et al. 2010), it should be in their strategic interest to protect relationships with customers. Therefore, anything that might harm those relationships deserves research attention. Addressing the fact that product returns may be perceived as service failures, we examine how returns may affect relational outcomes.

Hypotheses

Direct effects

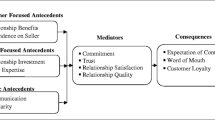

The primary objective of the current research is to investigate the relationship between product returns and key relational outcomes (see Fig. 1). In doing so, we respond to Pei et al.’s (2014) assertion that more research is needed into the consequences of customers’ product return behavior. The theory of cognitive dissonance is well suited for explaining the effect of product returns on consumer relational outcomes. Cognitive dissonance reflects a consumer’s state of psychological discomfort; the discomfort may arise when the consumer holds contradictory cognitions (Festinger 1957; Powers and Jack 2013). For example, when a consumer purchases a product online and finds it not to meet her expectations, she can feel dissonance because the comparison of what was expected versus what was received is not favorable. In this context, Buttle (1998, p. 248) argues that if “performance is below expectation, the customer might sense dissonance”. Such cognitive dissonance likely is associated with feelings of doubt and remorse (Powers and Jack 2013). We theorize that cognitive dissonance is always aroused whenever a consumer returns a product, irrespective of the return reason. Moreover, we posit that the relationships between returns, satisfaction, trust and positive word of mouth are moderated by customers’ monthly spending.

According to Statista (2014), the most frequent return reasons are products which do not fit or look as expected, especially in the fashion retail context, as well as product quality. In other words, delivered products do not appear as expected, indicating a discrepancy between the customer’s expectation and actual or perceived product characteristics. Perceived discrepancies between expectations and the actual performance of a good or service results in (dis)satisfaction (Day 1984; Oliver 1980). If this discrepancy is experienced repeatedly, customers likely become dissatisfied. In other words, this expectation-perception gap will trigger cognitive dissonance and affect customer satisfaction with the performance of the online retailer where the product was purchased.

-

H1a: Product returns are negatively related to customer satisfaction.

Trust encompasses the customer’s confidence in a seller’s reliability and integrity as well as the actual willingness to rely on this seller (Morgan and Hunt 1994). Consistent with the availability heuristic (Tversky and Kahneman 1973), we theorize that the customer’s recent product returns to a retailer will prompt cognitive dissonance and increase the perceived probability of future returns, leading to the belief that future orders will result in negative outcomes. Repeated past and expected future returns therefore might diminish the perceived trustworthiness of the retailer. In addition, previous returns, which are perceived as service failures will affect the perceived reliability of the retailer and thus affect trust (Weun et al. 2004).

-

H2a: Product returns are negatively related to customers’ trust.

Word-of-mouth is influenced directly by customers’ perceived value (Dai and Salam 2014), encompassing the “trade-off between benefits or gets (quality, convenience, volume, etc.) and costs or gives (money, time, efforts, etc.)” (De Matos and Rossi 2008, p. 582). Customers who return products will perceive low or negative value, as the costs in terms of handling the product return (i.e., repacking products, fill in forms, return package, and wait for refunding) might outweigh the benefits. Furthermore, De Matos and Rossi (2008) identified service quality as a word-of-mouth antecedent, conceptualized as the ability to meet or exceed customers’ expectations. Customers who repeatedly return products will have doubts regarding the quality of the online retailer. Some customers may engage in verbal communication in order to alleviate the discomfort caused by cognitive dissonance (Buttle 1998; Wangenheim and Bayón 2007). Put differently, those doubts will shape customers’ post-consumption behaviors, including their word-of-mouth behavior.

-

H3a: Product returns are negatively related to positive word-of-mouth.

Moderation effects

Customer spending, which directly determines firm revenues and profits, represents customer choice behavior which is associated with rational information (Epstein 1994) and customers’ overall satisfaction with the retailer (e.g., Babin and Darden 1996). Walsh et al. (2014) demonstrate that a service firm’s reputation and customer commitment is positively associated with customer spending. Thus, previous research suggests that customers are more willing to spend with retailers they find credible and with whom they want to be in an enduring relationship. However, when high-spending customers feel doubt and remorse in relation to certain aspects of the transactions with the retailer (i.e., returning products), the negative effect of product returns on relational outcomes will likely be confounded. Therefore:

-

H1b: Monthly spending moderates the negative relationship between product returns and customer satisfaction such that the relationship is strengthened.

-

H2b: Monthly spending moderates the negative relationship between product returns and customer trust such that the relationship is strengthened.

-

H3b: Monthly spending moderates the negative relationship between product returns and customer positive word of mouth such that the relationship is strengthened.

Method

Procedure and measures

A questionnaire with multiple-item scales adapted from literature for the constructs depicted in Fig. 1 was administered to members of an online panel. The questionnaire was pre-tested using a student sample. A random sample of customers from a consumer panel maintained by a market research firm was drawn. To be considered for the survey, panel members had to shop on a regular basis at multiple online retailers. Respondents were then randomly assigned to one of eight large online retailers operating in Germany, where they had been a customer in the past. Those retailers, which differed in terms of product assortment, were: Amazon, Conrad Electronics, Ebay, Ikea, Neckerman, Otto, Quelle, and Zalando.

As we use the same source for independent and dependent variables, our results may be affected by common method variance, which posits that a significant amount of variance explained is attributed to the measurement rather than to the theoretical foundations (Podsakoff et al. 2003). We used procedural as well as statistical remedies to reduce and assess the probability of common method variance. Regarding procedural remedies, we pre-tested all the items for clarity and assured anonymity to respondents, to reduce item characteristic effects.

Respondents had to answer all questions (e.g., regarding their satisfaction) in relation to the one online shop they were randomly assigned to. The sample size is 451. The sample is largely representative of German online shoppers in terms of age and gender (56% female). Each respondent reported the average number of product orders as well as his/her monthly spending in Euros with the online retailer. The product return rate was measured as the reported percentage of product purchases that were returned. Respondents were also asked about their return reasons. The main return reasons were the products not being the right size or not meeting expectations. We measured customer satisfaction (i.e., ‘I am satisfied with the services this online retailer provides’) and trust (i.e., ‘This is an online retailer that you can trust’) with one item, respectively; the items were taken from Tsai and Huang (2007) and Walsh et al. (2016). Word-of-mouth was measured with one item (i.e., ‘I am likely to say positive things about this retailer’) taken from Koufteros et al. (2014). The moderator, customer monthly spending, was measured as average spending per month (in Euros) at the retailer. Customers’ monthly purchases (i.e., average number of orders per month), age, and gender served as control variables.

In classical relationship theory, switching costs are considered as positively influencing relational qualities and outcomes (Morgan and Hunt 1994). Although procedural switching costs (e.g., evaluation costs, learning costs, set-up costs; Burnham et al. 2003) are quite low in the online retailing context, customers’ order frequency might increase switching costs (Pick and Eisend 2014). Therefore, we also control for the number of customers’ purchases (see Fig. 1).

Results

The correlations between the main model variables appear in Table 2.

To evaluate the potential threat of common method variance, we performed Harman’s single factor test (cf. Fuller et al. 2016) for all indicators that reflect the independent variable and the relational outcomes. When we performed Harman’s one-factor test to assess common method variance, a one-factor model was derived that explained considerably less than 50% of the variance. The one-factor model yielded a ratio χ2/df = 4.02, compared with χ2/df = 1.486, for the measurement model. The fact that the one-factor model fit was significantly worse than that of the measurement model suggests that common method bias is not an issue for our data.

To test our hypotheses, we fitted a structural equation model with five single-item measures representing product return rate, satisfaction, trust, word-of-mouth, monthly purchases, age, and gender (control variables) and the hypothesized relationships, using AMOS 22 with a maximum-likelihood estimator. To incorporate the control variable, monthly purchases, we applied a log transformation to this variable, as it appeared left skewed (i.e., many less frequent purchases, but some extreme numbers of purchases). The model fit is reasonably good with all indices above recommended levels: χ2/df = 1.545 (p = .159), GFI = .99, CFI = .99, NFI = .98, and RMSEA = .035.

As shown in Fig. 1, overall support was found for the hypothesized relationships between product returns and the three relational outcomes. Product returns negatively affect customer satisfaction (−.187, p < .001) and word-of-mouth (−.170, p < .001), confirming H1a and H3a. However, the proposed negative relationship between product returns and trust is significant only at the 10%-level (−.086, p = .067). We therefore can only mildly support H2a.

Regarding the moderating effect of monthly spendings, we find an effect for the relationship between returns and positive word of mouth, in support of H3b (−.137, p < .01; see Fig. 1). However, the relationships between returns and satisfaction (−.010, p = .831) and trust (−.056, p = .235) were not strengthened by customer spending. Therefore, H1b and H2b have to be rejected.

As assumed, the control variables monthly purchases, age, and gender are not negatively associated with the three outcomes. The variable monthly purchases does not affect customer satisfaction (.000, p = .995), trust (.033, p = .475), and positive word-of-mouth (.027, p = .552). Age does not affect customer satisfaction (.021, p = .652), trust (−.050, p = .290), and positive word-of-mouth (.062, p = .185). Also, gender shows no effect on customer satisfaction (.048, p = .316), trust (.035, p = .469), and positive word-of-mouth (.022, p = .640).

Even though not all hypotheses could be confirmed, the findings generally support the proposed negative effect of product returns on relationship marketing. Furthermore, the missing effect of the control variable monthly purchases indicates that customers’ repeated purchases are not necessarily associated to relational outcomes in short-term (i.e., within a month).

Discussion

The present research is premised on the assumption that customer product returns not only hurt firm profits in the short term, but also impair the relationship between the customer and the firm. Accordingly, this research addresses the question whether product returns harm online retailers’ relationships with their customers by negatively affecting key relational outcomes. Although not all hypotheses could be confirmed, we provide evidence for the negative effects of product returns on three key relationship marketing outcomes, namely customer satisfaction, trust and positive word-of-mouth. In addition, we show that customer monthly spendings exacerbate the negative effect of product returns on word of mouth, suggesting that when heavy shoppers have to return products their willingness to act as advocates of the retailer decreases.

Theoretical implications

Whilst some studies examined consequences of product returns—especially of return handling and policy in a broader sense (e.g., Bower and Maxham 2012; Griffis et al., 2012a; Mollenkopf et al. 2007; Ramanathan 2011; Zhou and Hinz 2015)—they did not assess the impact of product returns on relational outcomes. In addressing this oversight, our results show that product returns negatively impact key relational outcomes. Specifically, we demonstrate that product returns negatively affect customer satisfaction and word-of-mouth, and mildly influence trust. Our findings support our reasoning that returns commonly constitute a discrepancy between customers’ expectations and online retailers’ actual performance. As such, product returns are akin to service failures.

In contrast to Petersen and Kumar (2009), who show that product returns could increase subsequent purchases (up to a threshold) in a mixed retail context, we show that returns actually harm relational outcomes, such as customer satisfaction, in an online retail context. As customer satisfaction is an important predictor for future purchases (e.g., Gustafsson et al. 2005; Kim et al., 2009a; Zhang et al. 2011), our results suggest that product returns might decrease subsequent orders, thus complementing the findings presented by Petersen and Kumar (2009). A possible explanation for this deviating result might be that customers order alternative products after sending mismatching products back, so that returns are followed by subsequent higher short-term orders, while satisfaction decreases.

In contrast to customer satisfaction, which is key for customer retention, trust and word-of-mouth are major relational outcomes that help to attract new customers (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2002). Hence, our findings that product returns negatively affect trust and word-of-mouth communication indicate that product returns may even hinder customer attraction, especially because frustrated customers engage in more (negative) word-of-mouth than satisfied customers (Anderson 1998).

To sum up, our results (1) demonstrate the importance of considering relational outcomes as consequences of product returns and (2) contribute to the product returns literature as well as to relationship marketing theory by showing that product returns negatively affect customer satisfaction, trust and word-of-mouth.

Managerial implications

Product returns represent a key challenge for online retailers. The average percentages of products being returned are high as well as the concomitant costs for handling and reselling returns. Hence, retailers focus on causes of returns and possible interventions to reduce returns and save costs. On the other hand, previous research on product return consequences showed that customer-friendly returns are important for retailers’ long-term profitability (e.g., Bower and Maxham 2012; Zhou and Hinz 2015) and that product returns are related to increased subsequent purchases (Petersen and Kumar 2009), indicating that returns may even have positive consequences for customers and retailers. As a result, many firms make efforts to soften and promote their return policy, for example, by providing a ‘100 day return period’. Such policies likely contribute to higher return rates. Our findings suggest that product returns negatively affect relationship marketing outcomes. Specifically, product returns decrease customer satisfaction and negatively affect word-of-mouth.

Customers who order several alternative products will very likely send at least one item back after deciding to retain a product, and thus will not necessarily be dissatisfied. Therefore, it is important for retailers to distinguish between such ‘good returns’ (i.e., ordered different alternatives and returned a few products) and ‘bad returns’ (i.e., returned all products) to strengthen relational outcomes and profitability. For example, retailers could prevent ‘bad returns’ and push ‘good returns’ by encouraging customers to order additional product alternatives. Also, data mining of ‘good returns’ might help to improve alternative product recommendations (Neal 2011), and thus prevent future ‘bad returns’.

As mentioned earlier, further analysis of customers’ order history could be important because product returns and the resulting dissatisfaction might not decrease subsequent purchases in the short-term. Customers might order alternative products after sending mismatching products back. If customers need to return subsequently ordered alternatives again, this might even have a substantially more negative impact on relational outcomes. Moreover, due to switching costs, customers might change retailers only after a series of dissatisfying events. In contrast, a successful subsequent order (i.e., product retained) could eliminate the negative effect of the previous order. Retailers should therefore set up refined return data monitoring procedures (e.g., detect related orders) and consider intelligent return management strategies (e.g., provide customers with personalized product recommendations) to improve the customer’s satisfaction with future purchases.

When assessing the total costs of product returns, retailers should also include the indirect costs of decreased word-of-mouth communication. As positive word-of-mouth helps retailers to attract new customers and thus to save customer acquisition costs (e.g., by spending less for mass media and online marketing), decreased positive word-of-mouth will in turn increase retailers’ costs. Therefore, besides return handling costs, retailers should estimate the supplementary customer acquisition costs offsetting the word-of-mouth impact. Taken together, our results shed new light on what might be considered the ‘hidden’ consequences of product returns; hidden, because relationship outcomes are difficult to measure in practice.

Limitations and future research

The current research examined product returns of customers of eight large online retailers, ranging from single category (e.g., clothing, electronics) to multi category retailers. It may encourage future studies on the effect of product returns on relational outcomes in different product categories. Our research focused on three relational outcomes—customer satisfaction, trust and word-of-mouth. However, the effect on trust appears only marginally significant. As trust is a key relational quality in itself as well as a relational outcome, further research is required into the nature of the association between product returns and trust. Moreover, future research may examine other relational qualities and outcomes (e.g., loyalty, commitment) in relation to product returns. Although we used data from a customer panel, the data did not allow us to conduct a longitudinal analysis of customer return behavior. Future studies could investigate returns-relational outcomes relationships using longitudinal customer- and possibly firm-level data. Also, field experiments could be ideally suited to assess causality and in terms of external validity (Gneezy 2016).

Also, we do not elaborate on return reasons in this study. Future research is thus necessary to determine the impact of different return reasons for different product categories on relational outcomes. In this context, potential mediators and moderators will be helpful in understanding the underlying mechanism of product returns affecting customer relationships. We investigated the influence of customers’ return rate (relative numbers) in online retailing contexts. Multi-channel retailing, which is a retail business model that blends offline and online retail formats, may be associated with unique product return behaviors (Gallino and Moreno 2014). Considering the absolute amount of product returns of multi-channel customers within and across channels could be a fruitful research issue.

Moreover, customer dissatisfaction may be proportional to the returned products per order. In this context, future research should consider customer’s purchase order composition, for example the number of retained products in relation to the number of ordered products, the number of product alternatives (e.g., fashion product in different sizes and colors) or the number of impulsively ordered products. In doing so, research could examine the influence of different kinds of return circumstances on customer satisfaction. Relatedly, future research could explore the salience of product returns in decision-making situations. In other words, what is the probability that a consumer will think about returning the product in the decision-making situation? This ‘mental availability’ (cf. Romaniuk and Sharp 2004) is likely dependent on the recency of the last return (i.e., time elapsed since last return) and may mean that the consumer is more likely to return a product in cases when she thinks about returning it during online purchasing process. Furthermore, relational outcomes are linked to subsequent purchases. However, relational damage (e.g., to satisfaction) might unfold its effect over time. Therefore, future research should make use of longitudinal data to investigate the short-, mid- and long-term consequences of returns on relational and behavioral outcomes.

Finally, to deal with potential common method variance, we applied Harman’s one-factor test which is easy and fast to apply. Arguably, the marker variable technique, which provides a correction factor (cf. Malhotra et al., 2006), represents an even more robust assessment of common method variance. However, because of the costs associated with obtaining the data for this study, a marker variable (i.e., a variable theoretically unrelated to other items in the survey) was not included in the survey. Therefore, future studies are encouraged to employ the marker variable technique and other tests to assess common method variance.

References

Ahearne, M., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Gruen, T. (2005). Antecedents and consequences of customer-company identification: expending the role of relationship marketing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(3), 574–585.

Anderson, E. W. (1998). Customer satisfaction and word of mouth. Journal of Service Research, 1(1), 5–17.

Anderson, J. C., & Narus, J. A. (1990). A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships. Journal of Marketing, 54(1), 42–58.

Babin, B. J., & Darden, W. R. (1996). Good and bad shopping vibes: spending and patronage satisfaction. Journal of Business Research, 35(3), 201–206.

Berry, L. L. (1983). Relationship marketing. In L. L. Berry, G. L. Shostack, & G. Upah (Eds.), Emerging perspectives on services marketing (pp. 25–28). Chicago: American Marketing Association.

Blut, M., Beatty, S. E., Evanschitzky, H., & Brock, C. (2014). The impact of service characteristics on the switching costs–customer loyalty link. Journal of Retailing, 90(2), 275–290.

Bower, A. B., & Maxham III, J. G. (2012). Return shipping policies of online retailers: normative assumptions and the long-term consequences of fee and free returns. Journal of Marketing, 76(5), 110–124.

Brohan, M. (2013). Reducing the rate of returns, Internet Retailer. Retrieved September 24, 2015, from http://www.internetretailer.com/2013/05/29/reducing-rate-returns.

Burnham, T. A., Frels, J. K., & Mahajan, V. (2003). Consumer switching costs: a typology, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(2), 109–126.

Buttle, F. A. (1998). Word of mouth: understanding and managing referral marketing. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 6(3), 241–254.

Chuang, S.-C., Cheng, Y.-H., Chang, C.-J., & Yang, S.-H. (2012). The effect of service failure types and service recovery on customer satisfaction: a mental accounting perspective. The Service Industries Journal, 32(2), 257–271.

Dai, H., & Salam, A. F. (2014). Does service convenience matter? An empirical assessment of service quality, service convenience and exchange relationship in electronic mediated environment. Electronic Markets, 24(4), 269–284.

Day, R. L. (1984). Modeling choices among alternative responses to dissatisfaction. In T. C. Kinnear (Ed.), Advances in consumer research (Vol. 11, pp. 496–499). Provo: Association for Consumer Research.

De Matos, C. A., & Rossi, C. A. V. (2008). Word-of-mouth communications in marketing: a meta-analytic review of the antecedents and moderators. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(4), 578–596.

Dwyer, F. R., Schurr, P. H., & Oh, S. (1987). Buyer-seller developing relationships. American Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 11–27.

Epstein, S. (1994). Integration of the cognitive and the psychodynamic unconscious. American Psychologist, 49(8), 709–724.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. California: Stanford University Press.

Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198.

Gallino, S., & Moreno, A. (2014). Integration of online and offline channels in retail: the impact of sharing reliable inventory availability information. Management Science, 60(6), 1434–1451.

Galloway, G., Mitchell, R., Getz, D., Crouch, G., & Ong, B. (2008). Sensation seeking and the prediction of attitudes and behaviours of wine tourists. Tourism Management, 29(5), 950–966.

Gao, H., & Liu, D. (2014). Relationship of trustworthiness and relational benefit in electronic catalog markets. Electronic Markets, 24(1), 7–75.

Gefen, D. (2000). E-commerce: the role of familiarity and trust. Omega, 28(6), 725–737.

Gefen, D. (2002). Reflections on the dimensions of trust and trustworthiness among online consumers. SIGMIS Database, 33(3), 38–53.

Gneezy, A. (2016). Field experimentation in marketing research. Journal of Marketing Research, in press, doi:10.1509/jmr.16.0225.

Griffis, S. E., Rao, S., Goldsby, T. J., & Niranjan, T. T. (2012a). The customer consequences of returns in online retailing: an empirical analysis. Journal of Operations Management, 30(4), 282–294.

Griffis, S. E., Rao, S., Goldsby, T. J., Voorhees, C. M., & Deepak, I. (2012b). Linking order fulfillment performance to referrals in online retailing: an empirical analysis. Journal of Business Logistics, 33(4), 279–294.

Grönroos, C. (1990). Service management and marketing: managing the moments of truth in service competition. Lexington: Lexington Books.

Gummerus, J., Liljander, V., Weman, E., & Pihlström, M. (2012). Customer engagement in a Facebook brand community. Management Research Review, 35(9), 857–877.

Gustafsson, A., Johnson, M. D., & Roos, I. (2005). The effects of customer satisfaction, relationship commitment dimensions, and triggers on customer retention. Journal of Marketing, 69(4), 210–218.

Gwinner, K. P., Gremler, D. D., & Bitner, M. J. (1998). Relational benefits in services industries: the customer’s perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 26(2), 101–114.

Harris, L. C. (2008). Fraudulent return proclivity: an empirical analysis. Journal of Retailing, 84(4), 461–476.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. P., & Gremler, D. D. (2002). Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: an integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. Journal of Service Research, 4(3), 230–247.

Hui, M. K., Ho, C. K., & Wan, L. C. (2011). Prior relationships and consumer responses to service failures: a cross-cultural study. Journal of International Marketing, 19(1), 59–81.

Ibi research (2013). Retourenmanagement im online-Handel – Das Beste daraus machen. Ibi Research. Retrieved September 24, 2015, from: http://www.ibi.de/files/Retourenmanagement-im-Online-Handel_-_Das-Beste-daraus-machen.pdf.

Kim, D., & Benbasat, I. (2006). The effects of trust-assuring arguments on consumer trust in internet stores: application of Toulmin’s model of argumentation. Information Systems Research, 17(3), 286–300.

Kim, D. J., Ferrin, D. L., & Raghav Rao, H. (2009a). Trust and satisfaction, two stepping stones for successful e-commerce relationships: a longitudinal exploration. Information Systems Research, 20(2), 237–257.

Kim, T. T., Kim, W. G., & Kim, H.-B. (2009b). The effects of perceived justice on recovery satisfaction, trust, word-of-mouth, and revisit intention in upscale hotels. Tourism Management, 30(1), 51–62.

Koufteros, X., Droge, C., Heim, G., Massad, N., & Vickery, S. K. (2014). Encounter satisfaction in E-tailing: are the relationships of order fulfillment service quality with its antecedents and consequences moderated by historical satisfaction? Decision Sciences, 45(1), 5–48.

Laroche, M., Yang, Z., McDougall, G. H. G., & Bergeron, J. (2005). Internet versus bricks-and-mortar retailers: an investigation into intangibility and its consequences. Journal of Retailing, 81(4), 251–267.

Liao, C., Palvia, P., & Lin, H. N. (2010). Stage antecedents of consumer online buying behavior. Electronic Markets, 20(1), 53–65.

Lim, K., Sia, C., Lee, M., & Benbasat, I. (2006). Do I trust you online, and if so, will I buy? An empirical study of two trust-building strategies. Journal of Management Information Systems, 23(2), 233–266.

Maity, D., & Arnold, T. J. (2013). Search: an expense or an experience? Exploring the influence of search on product return intentions. Psychology and Marketing, 30(7), 576–587.

Malhotra, N. K., Kim, S. S., & Patil, A. (2006). Accounting for common method variance in IS research: reanalysis of past studies using a marker-variable technique. Management Science, 52(12), 1865–1883.

McNaughton, R. B., Osborne, P., Morgan, R. E., & Kutwaroo, G. (2001). Market orientation and firm value. Journal of Marketing Management, 17(5–6), 521–542.

Minnema, A., Bijmolt, T. H., Gensler, S., & Wiesel, T. (2016). To Keep or Not to Keep: Effects of Online Customer Reviews on Product Returns. Journal of Retailing, from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S002243591630001X.

Mollenkopf, D., Rabinovich, E., Laseter, T. M., & Boyer, K. K. (2007). Managing internet product returns: a focus on effective service operations. Decision Sciences, 38(2), 215–250.

Möller, K., & Halinen, A. (2000). Relationship marketing theory: its roots and direction. Journal of Marketing Management, 16(1–3), 29–54.

Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., & Deshpande, R. (1992). Relationships between providers and users of market research: the dynamics of trust within and between organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(3), 314–328.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38.

Müller, K. (2013). Zitiert! Robert Gentz und Rubin Ritter verraten die offizielle Retourenquote von zalando. Deutsche-Startups. Retrieved September 24, 2015, from http://www.deutsche-startups.de/2013/01/18/zitiert-retourenquote-zalando/.

Neal, M. (2011). Beyond trust: Psychological considerations for recommender systems. In: H. R. Arabnia, L. Deligiannidis, A. M. G. Solo & A. Bahrami (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2011 EEE International Conference on e-Learning, e-Business, Enterprise Information Systems, and e-Government (pp. 365–369). Las Vegas: EEE'11.

Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469.

Oliver, R. L. (1997). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Parvatiyar, A., & Sheth, J. N. (2000). The domain and conceptual foundations of relationship marketing. In J. N. Sheth & A. Parvatiyar (Eds.), Handbook of relationship marketing (pp. 3–38). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Pei, Z., Paswan, A., & Yan, R. (2014). E-tailer’s return policy, consumer′ s perception of return policy fairness and purchase intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21(3), 249–257.

Petersen, J. A., & Anderson, E. T. (2015). Leveraging product returns to maximize customer equity. In B. V. Kumar & D. Shah (Eds.), Handbook of research on customer equity in marketing (pp. 160–177). Cheltenham: Elgar Publishing.

Petersen, J. A., & Kumar, V. (2009). Are product returns a necessary evil? Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Marketing, 73(3), 35–51.

Pick, D., & Eisend, M. (2014). Buyers’ perceived switching costs and switching: a meta-analytic assessment of their antecedents. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42(2), 186–204.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Powers, T. L., & Jack, E. P. (2013). The influence of cognitive dissonance on retail product returns. Psychology & Marketing, 30(8), 724–735.

Ram, A. (2016). UK retailers count the cost of returns, Financial Times, Retrieved September 2, 2016, from: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/52d26de8-c0e6-11e5-846f-79b0e3d20eaf.html#axzz4CVRhobWZ. (accessed

Ramanathan, R. (2011). An empirical analysis on the influence of risk on relationships between handling of product returns and customer loyalty in E-commerce. International Journal of Production Economics, 130(2), 255–261.

Rao, S., Griffis, S. E., & Goldsby, T. J. (2011). Failure to deliver? Linking online order fulfillment glitches with future purchase behavior. Journal of Operations Management, 29(7–8), 692–703.

Romaniuk, J., & Sharp, B. (2004). Conceptualizing and measuring brand salience. Marketing Theory, 4(4), 327–342.

Sabiote, E. F., & Román, S. (2009). The influence of social regard on the customer–service firm relationship: the moderating role of length of relationship. Journal of Business and Psychology, 24(4), 441–453.

Shah, D., Kumar, V., Qu, Y., & Chen, S. (2012). Unprofitable cross-buying: evidence from consumer and business markets. Journal of Marketing, 76(3), 78–95.

Statista (2014). Welches sind die drei häufigsten Gründe für Retouren in Ihrem Online-Shop? Statista. Retrieved September 24, 2015, from: http://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/4423/umfrage/gruende-fuer-retouren-in-online-shops/.

The Economist (2013). Return to Santa – Ecommerce firms have a hard core of costly, impossible-to-please customers. Retrieved September 24, 2015, from: http://www.economist.com/news/business/21591874-e-commerce-firms-have-hard-core-costly-impossible-please-customers-return-santa.

Tsai, H. T., & Huang, H. C. (2007). Determinants of e-repurchase intentions: an integrative model of quadruple retention drivers. Information & Management, 44(3), 231–239.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: a heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5(2), 207–232.

Van Vaerenbergh, Y., Orsingher, C., Vermeir, I., & Lariviere, B. (2014). A meta-analysis of rela-tionships linking service failure attributions to customer outcomes. Journal of Service Research, 17(4), 381–398.

Walsh, G., Hennig-Thurau, T., Sassenberg, K., & Bornemann, D. (2010). Does relationship quality matter in e-services? A comparison of online and offline retailing. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 17(2), 130–142.

Walsh, G., Gouthier, M., Gremler, D. D., & Brach, S. (2012). What the eye does not see, the mind cannot reject: can call center location explain differences in customer evaluations? International Business Review, 21(5), 957–967.

Walsh, G., Bartikowski, B., & Beatty, S. E. (2014). Impact of customer-based corporate reputation on non-monetary and monetary outcomes: the roles of commitment and service context risk. British Journal of Management, 25(2), 166–185.

Walsh, G., Albrecht, A. K., Kunz, W., & Hofacker, C. F. (2016). Relationship between online retailers’ reputation and product returns. British Journal of Management, 27(1), 3–20.

Wang, S., Beatty, S. E., & Liu, J. (2012). Employees’ decision making in the face of customers’ fuzzy return requests. Journal of Marketing, 76(6), 69–86.

Wangenheim, F. V., & Bayón, T. (2007). The chain from customer satisfaction via word-of-mouth referrals to new customer acquisition. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(2), 233–249.

Weun, S., Beatty, S. E., & Jones, M. A. (2004). The impact of service failure severity on service recovery evaluations and post-recovery relationships. Journal of Services Marketing, 18(2), 133–146.

Weverbergh, R. (2013). The best kept secret in e-commerce is out. Here’s Zalando’s official return rate. Retrieved September 24, 2015, from: http://www.whiteboardmag.com/the-best-kept-secret-in-e-commerce-is-out-heres-zalandos-official-return-rate/.

Wood, S. L. (2001). Remote purchase environments: the influence of return policy leniency on two-stage decision processes. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 157–169.

Zhang, Y., Fang, Y., Wei, K., Ramsey, E., McCole, P., & Chen, H. (2011). Repurchase intention in B2C e-commerce—a relationship quality perspective. Information & Management, 48(6), 192–200.

Zhou, W. & Hinz, O. (2015). Determining profit-optimizing return policies – a two-step approach on data from taobao.com. Electronic Markets (Online Version of Record published before inclusion in an issue).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Hans-Dieter Zimmermann

Appendix

Appendix

Measures

Construct and item | Adapted from |

|---|---|

Customer satisfactiona | Tsai & Huang (2007) |

I am satisfied with the services this online retailer provides. | |

Customer trusta | Walsh et al. (2016) |

This is an online retailer that you can trust. | |

Customer positive word-of-moutha | Koufteros et al. (2014) |

I would say positive things about this online retailer to other people. | |

Customer monthly spending | Galloway et al. (2008) |

How much, on average, do you spend per month at this online retailer? | |

1 = up to 20 Euro | |

2 = 21 to 40 Euro | |

3 = 41 to 60 Euro | |

4 = 61 to 80 Euro | |

5 = 81 to 100 Euro | |

6 = more than 100 Euro |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Walsh, G., Brylla, D. Do product returns hurt relational outcomes? some evidence from online retailing. Electron Markets 27, 329–339 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-016-0240-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-016-0240-3