Abstract

Purpose

The authors examine the influence of employees’ social regard toward the customers on customer satisfaction, trust, and word of mouth. In addition, we analyzed the moderating role of length of relationship between the service provider and the customer on the effects of social regard on the customer relationship outcomes.

Design/Methodology/Approach

Hypotheses were tested with customers of two service industries: financial services and hair salon services. Data were gathered through telephone and personal interview surveys.

Findings

Findings reveal that social regard had a positive influence on customer satisfaction, trust, and positive word of mouth. Also, length of relationship seems to moderate the effect of social regard on customer satisfaction and trust, but not on word of mouth.

Implications

The key influence of employees’ social regard reveals that it can become a tool for the management of customer satisfaction, trust, and word of mouth. Aspects of staff training should be affected by these findings.

Originality/Value

Despite the importance that researchers and practitioners have assigned to the influence of employees’ behaviors on relational variables at the company level, employees’ social regard toward the customers not only remains unexplored but also has been confounded with other social variables. This research not only proves its effects on relational variables (satisfaction, trust, and word of mouth) but also shows the moderating role of length of relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In many service companies, contact employees are the source of differentiation and competitive advantage (Bettencourt and Brown 1997). Customer satisfaction, service quality perceptions and decisions to remain loyal or to switch service providers are significantly influenced by the attitudes and behaviors of these company representatives (e.g., Bitner et al. 1990; Román 2003). Poor core service could be compensated for by having good peripherals (Iacobucci et al. 1994). In this sense, friendly type behaviors of service staff have proved to improve service outcomes (i.e., Bitner et al. 1990; Iacobucci and Ostrom 1993). The range of friendly type behaviors include: friendliness, familiarity, flirting, caring, politeness, responsiveness, trustworthiness, helpfulness, and understanding. In this study, we focus on the social side of the customer–employee service interaction, and more specifically on perceived employee’s social regard toward the customer. This is particularly relevant since research has indicated that customers should be treated with respect; otherwise, they may feel insulted (Goodwin and Smith 1990) and consequently take their business elsewhere (Dubinsky 1994). In addition, respect or lack of respect for customers has been related to service quality evaluations (Bitran and Hoech 1990; Goodwin and Frame 1989), dissatisfaction (Dubinsky 1994), relationship strength (Barnes 1997), and loyalty (Dotson and Patton 1992). Likewise, courtesy of the service provider has been found to be an extremely powerful signal of service quality (Johnson and Zinkhan 1991).

In the few quantitative studies that have examined aspects of social regard, the concept has been confounded by other social variables in relational indices or used in narrow settings, such as service failures. Only recently Butcher et al. (2003) conceptualized and developed the first scale to measure social regard across the service industries of hairdressing, cafes, and naturopaths in Australia. They found initial support for social regard increasing customer service encounter satisfaction. Yet the effects of social regard on relational variables at the company level (e.g., satisfaction with the company, trust in the company, and positive word of mouth) remain unexplored. Satisfaction and trust have traditionally determined the quality of the relationship (Crosby et al. 1990). In addition, because services are generally experiential in nature and are therefore difficult to evaluate before purchase, word of mouth (WOM) seems particularly important to the marketing of services. Such communication exerts a strong influence on consumer purchasing behavior, influencing both short-term and long-term judgments (Herr et al. 1991). In particular, customers pay more attention to WOM, because it is perceived as credible and custom tailored and generated by people who are perceived as having no self-interest in pushing a product (Silverman 1997).

Also, various studies have considered the time-dependent effect of personal factors on relational constructs. For example, findings in the service literature indicate that as the relationship with the service provider matures, person-related aspects of the interaction (e.g., empathy and politeness) becomes less important for the customer (Coulter and Coulter 2002; Gounaris and Venetis 2002).

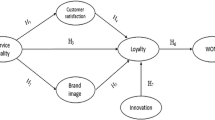

Consequently, the objectives of this research are (1) to test the influence of social regard on customer satisfaction with the company, trust in the company, and positive WOM and (2) to analyze the moderating role of length of relationship between the service provider and the customer on the effect of social regard on customer satisfaction, trust, and WOM. The following sections develop the hypotheses, test them empirically, and discuss the theoretical and managerial implications of the findings.

Conceptual Framework

Although there are services that are highly routinized and transactional in nature, many services that consumers require are specialized, require customization, and are of a personal nature (Zeithaml and Bitner 2000). These more personal encounters traditionally result in a great deal of repeated social interaction and elicit socioemotional responses (Barnes et al. 2000). And more importantly, empirical research has shown how certain consumers value human interaction above anything else in service delivery (e.g., Dabholkar 2000; Prendergast and Marr 1994).

Social aspects of the customer–frontline employee interaction have been widely identified in the service literature (e.g., Barnes 1997; Bitner et al. 1994; Farrell et al. 2001; Mittal and Lassar 1996; Van Dolen et al. 2002). However, scholars have not been consistent with the terminology used to label the social component of the personal interaction. This lack of consensus takes place not only regarding the term used, but also the construct’s domain which better captures it. For example, Stafford (1995) operationalized the employee–customer interaction construct to reflect how the service employee understood and related to the customer, and in particular treated the customer as an equal. Mittal and Lassar (1996, p. 96) defined personalization as the “social content of interaction between service employees and their customers”, whereas West (1997) referred to it as “sociality”.

Our research focuses on employees’ social regard as related to interactions with their customers and from the customers’ perspective. The key aspects that make up the social regard construct are: (1) making the customer feel important (Dotson and Patton 1992; Mohr and Bitner 1995), (2) taking an interest in the customer (Bitran and Hoech 1990), (3) respecting the customer (Barnes 1997; Bitran and Hoech 1990), (4) deference—referred to the courtesy, politeness, and thoughtfulness displayed by employees (Blodgett et al. 1995; Mohr and Bitner 1995), and (5) genuineness of behavior (Bitran and Hoech 1990; Mohr and Bitner 1995).

We acknowledge that definitions of constructs typically evolve during early stages of exploratory research (Van Dyne et al. 1995). However, definitional clarity is essential and must be resolved, before additional substantive research occurs (Schwab 1980). Consequently, based on Butcher et al.’s (2003) definition, we see social regard as employees’ behaviors characterized by deference, genuine respect, and interest such that the customer feels valued or important in the social interaction.

In following section, we explain the direct and indirect effects of employee’s social regard on customer satisfaction, trust in the company, and positive WOM. We then address the moderating role of length of relationship in such effects.

Relational Consequences of Perceived Employees’ Social Regard (Direct Effects)

We expect a positive association between social regard and customer satisfaction, trust in the company, and positive WOM. Overall, the reasoning behind these propositions is based on the key role of frontline employees in the service setting. That is, contact employees are the organization in the customer’s eyes and, in many cases, they are the service—there is nothing else (Zeithaml and Bitner 2000). Consequently, if the contact employees show social regard to their customers, the customers are likely to develop positive feelings toward the company because “customer perceptions of contact employees will affect their perceptions of the company” (Ganesh et al. 2000, p. 68).

Customer satisfaction. Satisfaction is an overall evaluation of performance based on all prior experiences with a firm (Anderson et al. 1994). Customers’ perceptions of the performance of service employees tend to determine not only encounter satisfaction but also satisfaction with the firm (Ganesh et al. 2000). As for the empirical evidence of the relationship between social regard and satisfaction, preliminary results from Butcher et al. (2001, 2003) provide equivocal evidence. In this sense, while Butcher et al. (2001) find that social regard is not associated significantly with service encounter satisfaction, results from Butcher et al. (2003) suggest a positive relationship between social regard and service satisfaction. Nevertheless, several actions closely related to social regard have been found to increase customer satisfaction. For example, Winsted (1997) found a positive relationship between the true concern for the customer in terms of caring, attentiveness, and kindness, and satisfaction with the encounter. Mittal and Lassar (1996) found that personalization had a positive effect on overall satisfaction. Recently, findings from Van Dolen et al. (2002) revealed that social competence perceived by the customer increased encounter satisfaction. Because customers’ perceptions of the performance of service employees tend to determine not only encounter satisfaction but also satisfaction with the firm (Ganesh et al. 2000), we expect a positive association between social regard and customer satisfaction and we state formally that

H1

Perceived employee’s social regard toward the customer is positively related to customer’s satisfaction with the organization.

Customer trust. Customer trust relates to the belief on the part of the customer that obligations will be fulfilled (Swan et al. 1999). In other words, the customer has confidence in the quality and reliability of the services offered by the organization (Garbarino and Johnson 1999). Following several researchers, we see trust as a global, unidimensional construct (e.g., Garbarino and Johnson 1999; Morgan and Hunt 1994).

Several researches suggest that service employees with whom the customer interacts are able to confirm and build trust in the organization (e.g., Oliver and Swan 1989; Zeithaml and Bitner 2000). From a theoretical perspective, it can be argued that consumers may initially require more assistance in understanding the attributes and benefits associated with their consumption because of the uncertainty and lack of knowledge associated with the service encounters. Consequently, based on Petty and Cacioppo (1986), we expect that actions on the part of the service representative, such as taking an interest in the customer and respecting him/her, will facilitate the communication of service-related information, thereby increasing consumers’ understanding of how the service operates. Further, these qualities should reduce interpersonal barriers and raise comfort levels, thereby alleviating perceptions of “riskiness” and contributing toward the establishment of trust in the service representatives, and in turn, in the company. As for the empirical evidence, results from Barnes (1997) suggest that actions included in the social regard construct, such as respecting the customers, increased relationship strength. Relationship strength, in turn, has been conceptualized by some researchers as a higher order construct consisting of trust among other variables (e.g., Bove and Johnson 2001). In addition, caring behaviors (e.g., genuine concern for the customer’s well being) have been found to have a positive influence on trust (Gremler et al. 2001). Based on the above discussion, we hypothesize that

H2

Perceived employee’s social regard toward the customer is positively related to customer trust in the organization.

Word of mouth. Word of mouth can be defined as consisting of “informal communications directed at other consumers about the ownership, usage or characteristics of particular goods and services and/or their sellers” (Westbrook 1987, p. 261). WOM is particularly important in the service industries, because customers often perceive high levels of risk and have difficulty in evaluating a service encounter (Gremler 1994). Moreover, prior research argues that WOM can be considered as an approach to loyalty conceptualization (Butcher et al. 2001). Although preliminary findings from Butcher et al.’s (2001) suggest that social regard does not influence customer loyalty, there is some empirical evidence favoring the effect of employee’s social regard on WOM. For instance, results from the qualitative study of Bitran and Hoech (1990), in the context of an electronic equipment company’s repair hotline service, indicated that “a customer who had been treated respectfully seemed more inclined to express his or her satisfaction” (p. 95). Similarly, findings from Dotson and Patton (1992), on consumer perceptions of department store services, revealed that when customers felt valued in the transaction, they were more likely to continue doing business with the store. Later, Mittal and Lassar (1996) found a positive and significant effect of personalization on positive WOM. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H3

Perceived employee’s social regard toward the customer is positively related to customer’s positive WOM.

Relationships Among the Outcome Variables (Indirect Effects)

There is a long-term orientation in the variable of trust, since it is also conceptualized as “a cumulative process that develops over the course of repeated, successful interactions” (Nicholson et al. 2001, p. 4). A highly satisfying experience with the service organization may not only reassure the customer that his or her trust in the service is well placed, but also enhance it (Singh and Sirdeshmukh 2000). That is, as Geyskens et al. (1999, p. 227) point out “satisfaction (which develops in the short run and is a report of past interactions) positively influences trust (which takes relatively longer to develop and has a more expectational quality to it)”. From an empirical perspective, results from the meta-analysis developed by Geyskens et al. (1999) in marketing channel relationships support the link between customer satisfaction with the organization and trust in the organization. Even though Johnson and Grayson (2005) found only partial support for the relationship between satisfaction and trust, recent findings from the services marketing literature reveal that satisfaction positively influences trust (e.g., Román 2003; Román and Ruiz 2005; Wiertz et al. 2004). For example, Román and Ruiz (2005) found that customer satisfaction leads to higher levels of customer trust in a sample of 630 relational bank customers. Because it is directly linked to meeting expectations, satisfaction over time reinforces the perceived reliability of the firm and contributes to trust (Singh and Sirdeshmukh 2000). Accordingly, we hypothesize that

H4

Customer’s satisfaction with the company is positively related to customer’s trust in the company.

Empirical evidence about the relationship between satisfaction and WOM has yielded inconsistent findings. Some studies find a positive influence of satisfaction on WOM (e.g., Bettencourt 1997; Bolton and Lemon 1999; Verhoef et al. 2002), whereas others found no significant relationship (e.g., Arnett et al. 2003; Bettencourt 1997; Reynolds and Beatty 1999). Yet research suggests that when a marketer delivers high satisfaction to consumers, the expectation is that the consumers will spread positive WOM (Brown et al. 2005; Hennig-Thurau et al. 2002). The positive effect of satisfaction on WOM can be explained by the fact that satisfied customers highly value the offered services (Bolton and Lemon 1999). For this reason, they will be more inclined to behave in a way that is beneficial to the company. Hence, we expect that

H5

Customer’s satisfaction with the company is positively related to customer’s positive WOM.

Trust is generally viewed as an essential ingredient for successful relationships (Morgan and Hunt 1994). In fact, loyalty to the firm will be greater when consumers have perceptions of trust or confidence in the service provider (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2002). For example, Berry (1995) argued that “customers who develop trust in service suppliers based on their experiences with them… have good reasons to remain in these relationships” (p. 242). Trust has been associated with many pro-firm related behaviors (Ganesan 1994; Morgan and Hunt 1994). In the services literature, earlier research reveals that trust has a positive influence on WOM (Gremler et al. 2001; Verhoef et al. 2002). Accordingly, we hypothesize the following:

H6

Customer’s trust in the company is positively related to customer’s positive WOM.

The Moderating Role of Length of Relationship

Length of relationship refers to the amount of time (in years) that a customer has worked with a service provider. This conceptualization is consistent with extant marketing research (Cooil et al. 2007; Coulter and Coulter 2002; Ensher et al. 2001). Several studies show that “new” customers differ from those who have for long been a client of their company (“old” customers) with respect to a number of aspects, such as the way of forming satisfaction and trust (e.g., Coulter and Coulter 2002; Gounaris and Venetis 2002; Mittal and Katrichis 2000; Nicholson et al. 2001). Some studies show that longer relationships are prone to negative influences that dampen the positive effects of relationship marketing activities (Grayson and Ambler 1999; Moorman et al. 1992). Hence, as relationships become longer, investments in certain social and economic resources may have diminishing marginal returns. On the contrary, younger buyer–seller relationships need more frequent interactions than older relationships because such interactions help buyers to acquire important information (Nicholson et al.). That is to say, the more encounters the customer has with the service provider, the more information is accumulated about the service offering and the company.

We expect that during the early stages of a service relationship, when the customer is unfamiliar with the service, personal delivery factors such as deference, respect, and genuine interest become important cues on which inferences of satisfaction and trust are made. In addition, these factors may signal the service employees’ interest in the customer and the value they place on the customer, facilitating the achievement of positive outcomes for the service company, such as increased levels of customer satisfaction and trust (Nicholson et al. 2001). As customers gain more direct service experience, these factors become less relevant as “surrogate cues” on which to base satisfaction and trust evaluations. For example, findings from Butcher et al. (2001), p. 321 revealed that “feelings of comfort arising from employee interactions are important to early evaluations of service quality and satisfaction”. In addition, Coulter and Coulter (2002) found that as relationship ages, the impact of politeness and empathy on trust decreased. Similarly, drawing on the marital literature, recent results from Rosen-Grandon et al. (2004) reveal that the effects of some marital interaction processes (e.g., communication and intimacy) on marital satisfaction diminish over time.

H7

The shorter the length of the relationship, the stronger the effect of perceived employee’s social regard toward the customer on customer satisfaction with the organization.

H8

The shorter the length of the relationship, the stronger the effect of perceived employee’s social regard toward the customer on customer trust in the organization.

There is no previous study, to our knowledge, that has analyzed the moderating role of length of relationship on the effect of services employees’ behaviors on WOM. Nevertheless, we expect that age of the relationship will not have a moderating effect on the influence of perceived social regard behaviors on customers’ intentions to make positive recommendations to others (WOM). Preliminary evidence from Verhoef et al.’s study (2002) reveal that the relationship age did not moderate the effect of customer satisfaction with service employee’s behaviors (e.g., providing individual attention) on customer referrals. Recently, Seiders et al. (2005) argued and found support for a nonmoderating effect of length of relationship on the influence of customer satisfaction with the purchase experience on repurchase intentions (a construct closely related to WOM). Accordingly, we formulate the following:

H9

The effect of perceived employee’s social regard toward the customer on WOM will not vary depending on the length of the relationship.

Methodology

Data Collection and Samples

Data were gathered from customers of two service industries (financial services and hair salon services) in a medium-sized city located in the south east of Spain. The characteristics of these services carry a certain level of employee–customer interaction in terms of social bonding that is necessary to testing our conceptual model (Auh 2005; Román 2003). This approach follows the research by Price et al. (1995) who argue that exploratory work is best conducted in a narrow domain, which can be explored thoroughly. Further, focusing on two industries facilitate the testing of hypotheses while reducing the chance that the results will be confounded by exogenous variables (Pettijohn et al. 2000).

In-depth interviews were first carried out with consumers of financial services as well as hair salon services in order to get a better understanding of the research variables. Additionally, two separate pretests using customers from both types of services were used to assess survey format and improve measures. As shown in Table 1, items were slightly modified to suit the specific context of the questionnaire usage (either financial services or hair salon services).

The first survey was conducted by telephone with a random sample of 154 financial service consumers, who were living in this Spanish city. Hundred and fifty customers answered the telephone survey completely. As in previous research (e.g., Ganesh et al. 2000), respondents were first asked two screening questions to check whether they currently had an account (any type) with a bank and qualify them as the household decision maker regarding banking services. Also, because some customers were likely to have accounts in multiple banks, the respondents (in such cases) were specifically requested to answer all the questions with respect to their primary bank. Fifty-four percentage of the respondents were female, 50% of them were between 26 and 45 years old, and 32.7% had a college degree. They had been working with their main bank an average of 16.5 years. There were 54.7% customers engaging with more than one bank, and 70.4% of those polled went to the bank twice or more per month.

Data for the second survey were gathered by means of personal interviews in a variety of locations (i.e., neighbourhoods, mall intercept) during 4 weeks. Because some customers are likely to use more than one hair salon, interviewers requested respondents (in such cases) to think about the hair salon they regularly go. The final sample comprised 331 respondents (of 357 recruited) who completed the questionnaires, 61% of the respondents were females. Forty-two percentage of them were between 26 and 45 years old, and 46% had a college degree. They had been using their main hair salon an average of 5.2 years. There were 47.4% customers visiting more than one hair salon and 62% of those polled went to the hair salon once every 2 months or (even) more often.

Measures

Butcher et al.’s (2003) scale confounds employee actions with customer feelings, whereas our conceptualization of social regard only focuses on perceived employee behaviors. Accordingly, based on a combination of qualitative analysis, a review of the relevant literature, and a survey pretest of the scale (e.g., Matsuno et al. 2002; Mentzer et al. 2001; Selnes and Sallis 2003), Butcher et al.’s five-item scale was modified by finally changing the wording of one item, adding two items,Footnote 1 and dropping two items from the original scale.

As for the remaining scales, all of them consisted of 10-point multiple-item Likert questions, ranging from “1 = totally disagree” to “10 = totally agree” (see Table 1). Customer satisfaction with the company was measured using a three-item scale adapted from Roberts et al. (2003). Customer trust in the company was assessed with four items adapted from Ramsey and Sohi (1997), Verhoef et al. (2002), and Roberts et al. (2003). Based on Maxham and Netemeyer (2002), WOM was approached by a three-item scale.

Exploratory factor analysis was performed on all items that confirmed the unidimensionality of the measures in both surveys. On the basis of item-total correlations, none of the items were eliminated (Saxe and Weitz 1982). Reliability of the measures was confirmed with composite reliability index and average variance extracted higher than the recommended levels of .6 and .5, respectively, in both surveys. The scales were further evaluated through confirmatory factor analysis using the maximum likelihood procedure in LISREL 8.50 (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1996). Convergent validity was assessed by verifying the significance of the t-values associated with the parameter estimates. As shown in Table 1, all t-values were positive and significant (p < .01). Discriminant validity was tested by comparing the average variance extracted by each construct to the shared variance between the construct and all other variables. For each comparison, the explained variance exceeded all combinations of shared variance in both surveys (see Table 2).

Results

Direct and Indirect Effects

We measured direct and indirect effects using structural equation modeling (SEM). SEM enables the researcher to examine authentic models of social science phenomena, involving multiple variables with complex patterns of interaction and assess both direct and indirect effects simultaneously. A SEM model consists of a set of latent variables representing theoretical constructs, their measurements or indicators, and the interrelationships between them. Latent variables are those representing theoretical constructs that cannot be observed directly. Latent variables are measured by a set of indicators (items), which are scales in a questionnaire.

The results of the hypothesized structural models yielded a good fit of the data in both samples (see Table 3). For example, the CFI and the NNFI were greater than .90 and the RMSEA and RMSR were not greater than .08 (Hair et al. 1998). The model explained 46% of the variance in customer’s satisfaction, 83% of the variance in trust, and 64% of the variance in positive WOM in the financial services sample and 49, 82, and 74%, respectively, in the hair salon sample. The data provided support for all the effects hypothesized in the conceptual model except for H2 and H6, which were partially supported. This is because the path from social regard to trust was not significant in the financial services sample, but it was significant in the hair salon sample. The opposite took place when examining the path from trust to WOM. Such results will be discussed later.

In addition to the direct effects, the indirect relationship between social regard and trust via satisfaction was examined. The indirect relationship between social regard and positive WOM via both satisfaction and trust was also tested. The results indicate a significant indirect path between social regard and trust in both samples (t-values = 7.23 and 9.76, respectively). The indirect effect of social regard on WOM through satisfaction or trust was also significant in the financial services sample (t-value = 5.70) and in the hair salon services sample (t-value = 8.38). Yet in the latter case the indirect effect of social regard on WOM took place via satisfaction, since the effect of trust on WOM was not significant.

Moderating Influence of Length of Relationship

We tested whether the impact of social regard on the relational outcomes was moderated by the length of relationship through multigroup LISREL analyses. Though moderated regression analysis is a widely accepted technique in social research, multiple group LISREL was considered to be a more appropriate method in this case, because relationships among latent constructs are considered.

Both samples were split into two groups (“young relationships” and “mature relationships”) at the median score on length of relationship to ensure within-group homogeneity and between-group heterogeneity (e.g., De Wulf et al. 2001). The models across the two groups are identical except that in one analysis, the social regard → dependent variable (i.e., satisfaction, trust, and WOM) parameter was restricted to be equal across the two groups (equal model), while in an alternative, second analysis, this parameter was allowed to vary across the two groups (more general model). In the financial services sample, the analyses showed that the decrease in chi-square distribution when moving from the restricted (equal) model to the more general model was not significant in either case. This indicates that the length of relationship did not moderate the effect of social regard on customer satisfaction, trust, and WOM in the financial services sample.

On the contrary, in the hair salon sample, the effect of social regard on satisfaction was significantly stronger in the “young relationships” group than in the “mature relationships” group (γ = .88, t = 15.39; γ = .55, t = 8.08, respectively). This was confirmed because the decrease in chi-square distribution when moving from the restricted (equal) model to the more general model was significant (χ2(1) = 118.05; p > 0.1). Similar results were obtained when trust was the dependent variable (χ2(1) = 9.11; p > 0.1; “young relationships” group: γ = .43, t = 9.08; “mature relationships” group: γ = .24, t = 5.75). As expected, the length of relationship did not moderate the effect of social regard on WOM. In summary, length of relationship moderates the effect of social regard on satisfaction and trust in the hair salon sample, but not in the financial services sample, which partially supports H7 and H8. H9 was supported since no moderating effect was found in either sample when WOM was the dependent variable.

Discussion of Findings and Implications

The current study further explores the role of noncore dimensions of service provision with an emphasis on how the customer is treated and whether such treatment is important to service evaluations. More specifically, we examined the direct and indirect effects of this behavior on customer satisfaction with the company, trust in the company and positive WOM in two different service industries: financial services and hair salon services. Furthermore, the moderating role of length of relationship was analyzed.

Overall, our research contributes to the services marketing literature in two ways. First, it expands significantly on the work of Butcher et al. (2003), by analyzing the effect of social regard on the customer–firm relationship in two different settings: financial services and hair salons. Our findings support the notion that customers’ perceptions of employee’s social regard play a key role in enhancing relational outcomes at the company level. More specifically, we found a strong and positive association between perceived employee’s social regard and satisfaction with the company (H1). Similarly, social regard positively and directly influenced WOM (H3). Interestingly, social regard had a direct and positive influence on trust in the hair salon sample, but we found no significant effect in the financial services sample. Consequently, H2 was partially supported. A plausible explanation of the different results obtained may be related to the service setting where data were gathered. That is, hair salons are services high in experience qualities, whereas financial services are high in credence qualities. The first ones can only be discerned after purchase or during consumption, whereas the second ones are characteristics that the customer may find impossible to evaluate even after purchase and consumption (Zeithaml and Bitner 2000). More specifically, “services high in credence qualities are the most difficult to evaluate because the consumer may be unaware of or may lack sufficient knowledge to appraise whether the offerings satisfy given wants or needs even after consumption” (Zeithaml and Bitner 2000, p. 31). In such a context, the responsive, courteous, and caring behavior of the service provider is likely to have a direct effect on satisfaction but not on trust. Such behaviors may be less of a requirement but function instead as value-added service attributes that affect satisfaction (Crosby and Stephens 1987), and therefore not be a priority when choosing among services in a risky purchase situation. Then, a satisfactory experience with recurring interaction with the service provider strengthens customer confidence. That is to say, consumers tend to use their own satisfying experience as an indicator of credence qualities of the service (Mittal 2004), and consequently, as a determinant of trust.

Nevertheless, in hair salons, attributes of service providers—such as responsiveness and deference—can be easily assessed through personal interactions with service providers, and as such are experience attributes that can determine customer trust in the service provider (Mittal 2004) For example, results from Ostrom and Iacobucci (1995) revealed that friendliness was more important for experience services than for credence services. Sharma and Patterson (1999), in the context of financial services, found that technical quality (i.e., the competency of the service provider in achieving the best return of investment for the client at acceptable levels of risk) was much more important in explaining customer trust than functional quality (i.e., the responsive, courteous, and caring behavior of the service provider). Similarly, research has shown that consumers use a higher level of impersonal information sources to reduce perceived risk—and consequently to increase trust—when buying credence services as opposed to experience services (Mitra et al. 1999).

As for the indirect effects, social regard influenced trust indirectly through satisfaction (H4). We found a significant association between satisfaction with the service company and trust. This emphasizes the importance of satisfaction as a mediating construct and suggests that satisfaction may be regarded as a building block for customer trust. Moreover, on the one hand, this is consistent with the conceptualization of satisfaction as an immediate response to consumption and trust as a more long-term relationship characteristic (Geyskens et al. 1999). In addition, customer satisfaction (H5) influenced WOM in both service settings but trust had a significant influence on WOM only in the financial service context. Once again, this result may be explained by the qualities that characterize each service. It seems that when customers have serious difficulties in evaluating the service characteristics, trust becomes an important determinant of WOM. In this sense, earlier research suggests that the role of trust in developing loyalty is more relevant in credence services as opposed to experience services (Hsieh et al. 2005). But more importantly, our results are consistent with Harrison-Walker (2001) who found that customers’ perceptions of service provider’s reliability, responsiveness, and assurance influenced WOM in the veterinary industry (a credence service) but not in the hair salon industry.

The second contribution of the study is related to the analysis of the moderating effect of length of relationship. In the hair salon sample, as expected, the length of relationship moderated the effect of social regard on customer satisfaction and trust, but not on WOM. In the financial services sample, consistent with H9, we found no moderating effect of length of relationship on the influence of social regard on WOM. Nevertheless, and contrary to expectations, the effects of social regard on satisfaction and trust were not moderated by length of relationship. These results can be explained by the characteristics of the financial services sample. This sample can be considered as a relatively mature sample in terms of the number of years that respondents had been associated with their main bank (mean = 16.5,Footnote 2 SD = 1.9). On the contrary, the hair salon sample was a more suitable sample in order to test for the moderating effects of length of relationship (mean = 5.2, SD = 6.4), as opposed to a mean of 16.5 years (SD = 11.9) in the financial services sample. Overall, our results provide partial support for H7 and H8 and full support for H9, suggesting that customers who have long-standing relationships with service providers may need fewer social interactions to maintain their levels of satisfaction and value.

The introduction of new technologies is rapidly changing the nature of the service business (Koernig 2003). Although personalized interaction is time consuming for employees, our findings indicate that social regard behaviors are an effective way to strengthen the firm’s relationships with their customers. Moreover, being respectful and attentive to customers is a low-cost approach to building and maintaining a customer database (Dubinsky 1994). Consequently, we encourage companies to strengthen employees’ social regard behaviors.

Social regard represents an important construct to take into account in the strategic management of human resources. Aspects of staff training must be affected by the findings from this study. Employers need to teach and show employees how to treat customers with respect and dignity. Specifically, training programs may need to be upgraded. For instance, this training may be contrary to the classic flight attendant training based on “Your smile is your biggest asset… Really smile” (Hochschild 1983, p. 4), as it should point out that the customers value employees’ genuineness behavior. In addition, service firms may wish to empower their staff to behave according to social regard, achieving the goal of making the customer feel well regarded. Employees could be encouraged to monitor and adapt to different customer under different circumstances rather than follow a fixed script. Employees’ social regard should be evaluated and rewarded, as a way to encourage this behavior among frontline employees. Finally, we suggest services companies to encourage social regard behaviors at the early stages of the relationship, whereas offer-related service representative characteristics (e.g., competence, promptness, and reliability) should be emphasized in longer relationships. The previously discussed implications should be viewed within the limitations of this study. Our study has been developed in a high-context culture country. Social features of the service offering might be more important in a high-context culture country than in a low-context culture country. Low-context cultures rely on formal communication that is often verbally expressed. The social context of interactions is relatively less important (Hall 1976). Instead the emphasis is on promptness, saving time, and keeping to schedules. In high-context cultures, less information is contained in verbal expression, since much more is in the context of communication, which includes information such as the individual background, associations, values, and position in society (Keegan 1989). Accordingly, we encourage further research to compare the effects of social regard on customer relational outcomes between a high-context culture country and a low-context culture country.

This study focused on length of relationship because it represents an investment both parties make in the relationship (Kim and Ahn 2006). Because longer relationships are qualitatively different than shorter ones, there is value in research that focuses specifically on either type of relationship in order to understand better the dynamics of each. Yet further studies may investigate the moderating role of other variables such as depth or closeness of the relationship. These variables will characterize customer relationship with a service firm, distinguishing strong, warm, positive customer relationships from weak, indifferent (absent), or even negative relationships.

We have focused on the customer’s perspective, though further studies of social regard could investigate the construct from the perspective of the service provider. Research on this topic might take a dyadic approach, considering differences between service provider and customer perceptions of social regard, and thus analyzing how social regard—as perceived by the service provider—influences the quality of the relationship—as perceived by the customer.

In summary, our findings highlight the importance of treating the customer (a) as any person would like to be treated and (b) that is with respect and courtesy (Aaker 1991).

Notes

For the financial services sample: “The staff that I usually deal with refer to me by name”, which represented an action by which employees can make the customer ‘feel important’, and “They are discreet when discussing my financial affairs”, which refers to the employees’ deference in terms of discretion and thoughtfulness when dealing with customers. For the hair salon sample: “The staff that know me refer to me by name” and “They are discreet when talking to me”.

We looked for further descriptive sample evidence to support this explanation. Differences of satisfaction (mean = 7.35, standard deviation = 2.22 in the “mature” group; and mean = 7.06, standard deviation = 1.57 in the “young” group) and trust (mean = 7.46, standard deviation = 1.85 in the “mature” group; and mean = 7.12, standard deviation = 1.51 in the “young” group) levels in each sub-sample were not significant. Even though the mean values of relationship length are significantly different (mean = 28, standard deviation = 8.9 in the “mature” group; and mean = 8, standard deviation = 4.5 in the “young” group), we have to take into account that the mean value of relationship length (8 years) is quite high even in the “young” sub-sample. For example, testing for a similar moderating analysis, Liu et al. (2005) distinguished between a short relationship sub-sample (less than 3 years) and long relationship sub-sample (3 years or more).

References

Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity. New York: The Free Press.

Anderson, E., Fornell, C., & Lehman, D. R. (1994). Customer satisfaction, market share, an profitability: Findings from Sweden. Journal of Marketing, 58, 53–66.

Arnett, D. B., German, S. D., & Hunt, S. D. (2003). The identity salience model of relationship marketing success: The case of nonprofit marketing. Journal of Marketing, 67, 89–105.

Auh, S. (2005). The effects of soft and hard service attributes on loyalty: The mediating role of trust. Journal of Services Marketing, 19(2), 81–92.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(2), 74–94.

Barnes, J. G. (1997). Closeness, strength, and satisfaction: Examining the nature of relationships between providers of financial services and their retail customers. Psychology & Marketing, 14(8), 765–790.

Barnes, J. G., Dunne, P. A., & Glynn, W. J. (2000). Self-service and technology: Unanticipated and unintended effects on customer relationships. In T. A. Swartz & D. Iacobucci (Eds.), Handbook of services marketing & management (pp. 89–102). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Berry, L. L. (1995). Relationship marketing of services growing interest, emerging perspectives. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23, 236–245.

Bettencourt, L. A. (1997). Customer voluntary performance: Customers as partners in service delivery. Journal of Retailing, 73(3), 383–406.

Bettencourt, L. A., & Brown, S. W. (1997). Contact employees: Relationships among workplace fairness, job satisfaction and prosocial service behaviors. Journal of Retailing, 73(1), 39–61.

Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Mohr, L. A. (1994). Critical service encounters: The employee′s viewpoint. Journal of Marketing, 58, 95–106.

Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Tetreault, M. S. (1990). The service encounter: Diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. Journal of Marketing, 54, 71–84.

Bitran, G. R., & Hoech, J. (1990). The humanization of service: Respect at the moment of truth. Sloan Management Review, 31(2), 89–96.

Blodgett, J. G., Wakefield, K. L., & Barnes, J. H. (1995). The effects of customer service on consumer complaining behavior. Journal of Services Marketing, 9(4), 31–42.

Bolton, R. N., & Lemon, K. N. (1999). A dynamic model of customers’ usage of services: Usage as an antecedent and consequence of satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(2), 171–186.

Bove, L. L., & Johnson, L. W. (2001). Customer relationships with service personnel: Do we measure closeness, quality or strength? Journal of Business Research, 54, 189–197.

Brown, T. J., Barry, T. E., Dacin, P. A., & Gunst, R. F. (2005). Spreading the word: Investigating antecedents of consumers’ positive word-of-mouth intentions and behaviors in a retailing context. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33(2), 123–138.

Butcher, K., Sparks, B., & O’Callaghan, F. (2001). Evaluative and relational influences on service loyalty. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 12(4), 310–327.

Butcher, K., Sparks, B., & O’Callaghan, F. (2003). Beyond core service. Psychology & Marketing, 20(3), 187–208.

Cooil, B., Keiningham, T. L., Aksoy, L., & Hsu, M. (2007). A longitudinal analysis of customer satisfaction and share of wallet: Investigating the moderating effect of customer characteristics. Journal of Marketing, 71, 67–83.

Coulter, K. S., & Coulter, R. A. (2002). Determinants of trust in a service provider: The moderating role of length of relationship. Journal of Services Marketing, 16(1), 35–50.

Crosby, L. A., Evans, K. R., & Cowles, D. (1990). Relationship quality in services selling: An interpersonal influence perspective. Journal of Marketing, 54, 68–81.

Crosby, L. A., & Stephens, N. (1987). Effects of relationship marketing on satisfaction, retention, and prices in the insurance industry. Journal of Marketing Research, 24, 404–411.

Dabholkar, P. A. (2000). Technology in service delivery: Implications for self-service and service support. In T. A. Swartz & D. Iacobucci (Eds.), Handbook of services marketing & management (pp. 103–110). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

De Wulf, K., Odekerken-Schröder, G., & Iacobucci, D. (2001). Investments in consumer relationships: A cross-country and cross-industry exploration. Journal of Marketing, 65, 33–50.

Dotson, M., & Patton, W. E. (1992). Consumer perceptions of department store service: A lesson for retailers. Journal of Services Marketing, 6(2), 15–28.

Dubinsky, A. J. (1994). What marketers can learn from the Tin Man. Journal of Services Marketing, 8, 36–45.

Ensher, E. A., Thomas, C., & Murphy, S. E. (2001). Comparison of traditional, step-ahead, and peer mentoring on protégés’ support, satisfaction, and perceptions of career success: A social exchange perspective. Journal of Business and Psychology, 15(3), 419–438.

Farrell, A. M., Souchon, A. L., & Durden, G. R. (2001). Service encounter conceptualisation: Employees’service behaviours and customers’service quality perceptions. Journal of Marketing Management, 17, 577–593.

Ganesan, S. (1994). Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 58, 1–19.

Ganesh, J., Arnold, M. J., & Reynolds, K. E. (2000). Understanding the customer base of service providers: An examination of the differences between switchers and stayers. Journal of Marketing, 64, 65–87.

Garbarino, E., & Johnson, M. S. (1999). The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. Journal of Marketing, 63, 70–87.

Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J. B. E. M., & Kumar, N. (1999). A meta-analysis of satisfaction in marketing channel relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 36, 223–238.

Goodwin, C., & Frame, C. D. (1989). Social distance within the service encounter: Does the consumer want to be your friend? In Advances in Consumer Research (vol. 16). Provo, UT: Association of Consumer Research.

Goodwin, C., & Smith, K. L. (1990). Courtesy and friendliness: Conflicting goals for the service provider. Journal of Services Marketing, 4, 5–20.

Gounaris, S. P., & Venetis, K. (2002). Trust in industrial service relationships: Behavioral consequences, antecedents and the moderating effect of the duration of the relationship. Journal of Services Marketing, 16(7), 636–655.

Grayson, K., & Ambler, T. (1999). The dark side of long-term relationships in marketing services. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(1), 132–141.

Gremler, D. D. (1994). Word-of-mouth about service providers: An illustration of theory development and marketing. In C. W. Park, & S. C. Smith (Eds.), AMA winter educators' conference proceedings (Vol. 5, pp. 62–70). Chicago: American Marketing Association.

Gremler, D. D., Gwinner, K. P., & Brown, S. W. (2001). Generating positive word-of-mouth communication through customer-employee relationships. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 12(1), 44–59.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press.

Harrison-Walker, L. J. (2001). The measurement of word-of-mouth communication and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential antecedents. Journal of Service Research, 4(1), 60–75.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. P., & Gremler, D. D. (2002). Understanding relationship marketing outcomes. An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. Journal of Service Research, 4(3), 230–247.

Herr, P. M., Kardes, F. R., & Kim, J. (1991). Effects of word-of-mouth and product-attribute information on persuasion: An accessibility-diagnosticity perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 17(4), 454–462.

Hochschild, A. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Hsieh, Y. C., Chiu, H. C., & Chiang, M. Y. (2005). Maintaining a committed online customer: A study across search-experience-credence products. Journal of Retailing, 81(1), 75–82.

Iacobucci, D., Grayson, K. A., & Ostrom, A. (1994). The calculus of service quality and customer satisfaction. In T. A. Swartz, D. E. Bowen, & S. W. Brown (Eds.), Advances in services marketing and management, 7 (pp. 1–67). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press Inc.

Iacobucci, D., & Ostrom, A. (1993). Gender differences in the impact of core and relational aspects of services on the evaluation of service encounters. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2(3), 257–286.

Johnson, D., & Grayson, K. (2005). Cognitive and affective trust in service relationships. Journal of Business Research, 58(4), 500–507.

Johnson, M., & Zinkhan, G. M. (1991). Emotional responses to a professional service encounter. Journal of Services Marketing, 2, 5–15.

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1996). LISREL 8: user’s reference guide (2nd ed.). Chicago: Scientific Sowftware International Inc.

Keegan, W. J. (1989). Global marketing management. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kim, M. S., & Ahn, J. H. (2006). Comparison of trust sources of an online market-maker in the e-marketplace: Buyer's and seller's perspectives. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 47(1), 84–94.

Koernig, S. K. (2003). E-scapes: The electronic physical environment and service tangibility. Psychology & Marketing, 20(2), 151–167.

Liu, A. H., Leach, M. P., & Bernhardt, K. L. (2005). Examining customer value perceptions of organizational buyers when sourcing from multiple vendors. Journal of Business Research, 58(5), 559–568.

Matsuno, K., Mentzer, J. T., & Özsomer, A. (2002). The effects of entrepreneurial proclivity and market orientation on business performance. Journal of Marketing, 66, 18–32.

Maxham, J. G., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2002). A longitudinal study of complaining customers’evaluations of multiple service failures and recovery efforts. Journal of Marketing, 66, 57–71.

Mentzer, J. T., Flint, D. J., & Hult, T. M. (2001). Logistics service quality as a segment-customized process. Journal of Marketing, 65, 82–104.

Mitra, K., Reiss, M. C., & Capella, L. M. (1999). An examination of perceived risk, information search and behavioral intensions in search, experience and credence services. Journal of Services Marketing, 13(3), 208–825.

Mittal, B. (2004). Lack of attribute searchability: Some thoughts. Psychology & Marketing, 21(6), 443–462.

Mittal, V., & Katrichis, J. M. (2000). Distinctions between new and loyal customers. Marketing Research, 12(1), 26–32.

Mittal, B., & Lassar, W. M. (1996). The role of personalization in service encounters. Journal of Retailing, 72(1), 95–109.

Mohr, L. B., & Bitner, M. J. (1995). The role of employee effort in satisfaction with service transactions. Journal of Business Research, 32, 149–177.

Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., & Deshpande, R. (1992). Relationships between providers and users of market research: The dynamics of trust within and between organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(3), 314–328.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58, 20–38.

Nicholson, C. Y., Compeau, L. D., & Sethi, R. (2001). The role of interpersonal liking in building trust in long-term channel relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29(1), 3–15.

Oliver, R. L., & Swan, J. E. (1989). Consumer perceptions of interpersonal equity and satisfaction in transactions: A field survey approach. Journal of Marketing, 53, 21–35.

Ostrom, A., & Iacobucci, D. (1995). Consumer trade-offs and the evaluation of services. Journal of Marketing, 59(1), 17–28.

Pettijohn, C. E., Pettijohn, L. S., & Taylor, A. J. (2000). Research note: An exploratory analysis of salesperson perceptions of the criteria used in performance appraisals, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. The Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 20(2), 77–80.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 19, pp. 123–205). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Prendergast, G. P., & Marr, N. E. (1994). Disenchantment discontinuance in the diffusion of technologies in the service industry: A case study in retail banking. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 7(2), 25–40.

Price, L. L., Arnould, E. J., & Tierney, P. (1995). Going to extremes: Managing service encounters and assessing provider performance. Journal of Marketing, 59(2), 83–97.

Ramsey, R. P., & Sohi, R. S. (1997). Listening to your customers: The impact of perceived salesperson listening behavior on relationship outcomes. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(2), 127–137.

Reynolds, K. E., & Beatty, S. E. (1999). Customer benefits and company consequences of customer-salesperson relationships in retailing. Journal of Retailing, 75(1), 11–32.

Roberts, K., Varki, S., & Brodie, R. (2003). Measuring the quality of relationships in consumer services: An empirical study. European Journal of Marketing, 37(1/2), 169–196.

Román, S. (2003). The impact of ethical sales behaviour on customer satisfaction, trust and loyalty to the company: An empirical study in financial services industry. Journal of Marketing Management, 19, 915–939.

Román, S., & Ruiz, S. (2005). Relationship outcomes of perceived ethical sales behaviour: The customer’s perspective. Journal of Business Research, 58(4), 439–445.

Rosen-Grandon, J. R., Myers, J. E., & Hattie, J. A. (2004). The relationship between marital characteristics, marital interaction processes, and marital satisfaction. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82, 58–68.

Saxe, R., & Weitz, B. A. (1982). The SOCO scale: A measure of customer orientation of salespeople. Journal of Marketing Research, 19, 343–351.

Schwab, D. P. (1980). Construct validity in organizational behavior. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 2, pp. 3–43). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Seiders, K., Voss, G. B., Grewal, D., & Godfrey, A. (2005). Do satisfied customers buy more? Examining moderating influences in a retailing context. Journal of Marketing, 69, 26–43.

Selnes, F., & Sallis, J. (2003). Promoting relationship learning. Journal of Marketing, 67, 80–95.

Sharma, N., & Patterson, P. G. (1999). The impact of communication effectiveness and service on relationship commitment in consumer, professional services. Journal of Services Marketing, 13(2), 151–169.

Silverman, G. (1997). How to harness the awesome power of word of mouth. Direct Marketing, 60(7), 32–37.

Singh, J., & Sirdeshmukh, D. (2000). Agency and trust mechanisms in consumer satisfaction and loyalty judgements. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 150–167.

Stafford, M. R. (1995). How customers perceive service quality. Journal of Retail Banking, 17, 29–37.

Swan, J. E., Bowers, M. R., & Richardson, L. D. (1999). Customer trust in the salesperson: An integrate review an meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Journal of Business Research, 44(2), 93–107.

van Dolen, W., Lemmink, J., de Ruyter, K., & de Jong, A. (2002). Customer-sales employee encounters: A dyadic perspective. Journal of Retailing, 78, 265–279.

van Dyne, L., Cummings, L. L., & McLean, P. J. (1995). Extra-role behaviors: In pursuit of construct and definitional clarity (a bridge over muddied waters). Research in Organizational Behavior, 17, 215–285.

Verhoef, P. C., Franses, P. H., & Hoekstra, J. C. (2002). The effect of relational constructs on customer referrals and number of services purchased from a multiservice provider: Does age of relationship matter? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(3), 2002–2216.

West, D. C. (1997). Purchasing professional services: The case of advertising agencies. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 33(3), 2–9.

Westbrook, R. A. (1987). Product/consumption-based affective responses and postpurchase processes. Journal of Marketing Research, 24, 258–270.

Wiertz, C., de Ruyter, K., Keen, C., & Streukens, S. (2004). Cooperating for service excellence in multichannel service systems: An empirical assessment. Journal of Business Research, 57(4), 424–436.

Winsted, K. F. (1997). The service encounter in two cultures: A behavioral perspective. Journal of Retailing, 73(3), 337–360.

Zeithaml, V. A., & Bitner, M. J. (2000). Services marketing: Integrating customer focus across the firm (2nd ed.). Hill: McGraw.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Received and reviewed by former editor, George Neuman.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sabiote, E.F., Román, S. The Influence of Social Regard on the Customer–Service Firm Relationship: The Moderating Role of Length of Relationship. J Bus Psychol 24, 441–453 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-009-9119-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-009-9119-z