Abstract

The current review sought to describe the implementation and evaluation of trauma-focused school practices as represented in the published literature. Through a systematic literature search, we identified 39 articles describing trauma-focused practices implemented in school settings with elementary populations and coded data regarding these interventions’ characteristics as well as their implementation and evaluation procedures. Reviewed interventions were most often implemented by external clinicians or researchers with select populations in response to traumatic events experienced by a community (e.g., natural disaster, political violence). Additionally, interventions were most frequently evaluated solely using rating scales assessing psychopathological symptoms and without consideration of important dimensions such as treatment integrity, fidelity, and acceptability as well as outcome generalization and maintenance. We call for coordinated practice and research agendas focused on embedding trauma-focused practices within integrated multi-tiered systems of supports; designing culturally sensitive practices and training school personnel to serve as intervention agents; and increasing the rigor and broadening the methods, informants, and foci of screening and intervention evaluation procedures in the direction of leveraging multi-method, multi-informant, strengths-based assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Unfortunately, exposure to trauma is common in childhood (e.g., Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, & Hamby, 2015) and marked by potentially devastating effects. Children who have experienced trauma are at increased risk of impairments in not only emotional functioning but also behavioral, social, and academic functioning (Perfect, Turley, Carlson, Yohanna, & Saint Gilles, 2016; Porche, Costello, & Rosen-Reynoso, 2016). The range and cascade of negative outcomes associated with children’s experience of chronic trauma represent a significant public health concern and barrier to school success (Overstreet & Mathews, 2011).

To promote the functioning and well-being of individuals who have experienced trauma and prevent (re)traumatization, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (2014) advocates use of a trauma-informed approach to prevention and intervention. This approach represents a variety of practices that involve (a) realizing the effects of trauma on individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities; (b) recognizing the signs and symptoms of trauma; (c) responding by integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and (d) actively resisting re-traumatization, and that are characterized by the principles of safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment, voice, and choice; and consideration of cultural, historical, and gender issues (paraphrased from pp. 9–10). SAMHSA has advocated that a trauma-informed approach, involving trauma-focused (or trauma-specific) practices, be embedded within service sectors and public institutions such as schools.Footnote 1

Trauma-Focused Practices in Schools

The prevalence and effects of childhood trauma coupled with the opportune setting of schools for mental health service provision have led many to call for the adoption of trauma-focused practices within school settings (e.g., Cole, Eisner, Gregory, & Ristuccia, 2013; Little & Akin-Little, 2013; Overstreet & Chafouleas, 2016). These efforts have been strengthened by the Every Student Succeeds Act’s (ESSA; PL 114–95) provisions for supporting schools in implementing a trauma-informed approach (National Association of School Psychologists [NASP], 2016) and have furthermore been reflected through increases in publications related to school-based, trauma-focused practices. For example, in 2016, School Mental Health published a special issue on trauma-sensitive schools that included empirical studies related to the assumptions of trauma-informed approaches, case studies of trauma-focused practices, and a blueprint for implementing trauma-focused practices within multi-tiered frameworks (Chafouleas, Johnson, Overstreet, & Santos, 2016).

Missing from both the School Mental Health special issue and the remaining extant literature, however, is a narrative review of school-based, trauma-focused intervention studies that describes the characteristics, implementation, and evaluation of these practices. Existing reviews with related foci have been published, including some that have synthesized social-emotional interventions with specific populations known to be at risk of trauma (e.g., refugees and immigrants; Sullivan & Simonson, 2016) and others that have examined trauma-focused practices but have not restricted the implementation setting to schools (e.g., Birur, Moore, & Davis, 2017). School mental health efforts commonly face a range of implementation challenges related to, for example, competing priorities (e.g., achievement outcomes, teacher accountability) and systems-governed limitations (e.g., schedule inflexibility, teacher union restrictions on training time) (e.g., Fabiano, Chafouleas, Weist, Sumi, & Humphrey, 2014). These challenges typically differentiate the process, feasibility, and fidelity of school-based implementation relative to implementation in other settings, such that a trauma-focused intervention evaluated with promising effects in a clinical setting may flounder in a school setting. Thus, focusing a review on articles with school-based implementation may overcome issues associated with heterogeneity in setting.

In one such review, Rolfsnes and Idsoe (2011) analyzed 19 studies published between 1997 and 2010; however, these authors restricted their sample in a number of ways (e.g., excluded articles that did not use standardized instruments for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD] symptoms, that included students experiencing maltreatment, and/or that failed to provide sufficient data to compute effect sizes), notably by including only articles focused on reduction in PTSD symptoms. By limiting their article sample in this way, Rolfsnes and Idsoe reviewed only high-intensity trauma-focused practices on the single outcome of PTSD symptoms (i.e., aimed at promoting students’ return to prior functioning after experiencing adverse effects from trauma; Chafouleas et al., 2016).

In their blueprint for implementing trauma-focused practices in schools, Chafouleas et al. (2016) emphasize the utility of providing services of varying intensities within a multi-tiered framework. They also advocate targeting four primary outcomes through trauma-focused practices: preventing adverse events and experiences, fostering self-regulation skills, assisting students experiencing adverse effects from trauma in returning to prior level of functioning, and preventing future traumatization for students who have experienced adverse events, with Rolfsnes and Idsoe’s (2011) review only focusing on one of these outcomes. Moreover, Rolfsnes and Idsoe’s review was published prior to SAMHSA’s dissemination of trauma-informed service delivery guidelines (2014), ESSA’s passage (2015), and the publication of School Mental Health’s special issue on trauma-informed service delivery (2016). Thus, a review of broader and more recent articles is necessitated during this important time in the movement for trauma-sensitive schools.

Objectives of the Review

Narrative reviews of intervention literature may be particularly influential on both practice and future research (Baumeister & Leary, 1997). Summarizing what interventions were implemented how, with what populations, and with what effects may guide practitioners in selecting, designing, and implementing trauma-focused practices that best serve their students. Similarly, synthesizing the foci, methods, implications, and limitations of existing studies may assist researchers in designing and conducting additional research that meaningfully contributes to the literature.

The current review sought to describe the published literature on school-based implementation of trauma-focused services to assist practitioners in designing implementation and evaluation practices and guide researchers in identifying areas in need of additional development and evaluation. Specifically, the review sought to answer two questions: (1) What types of school practices are identified as trauma-focused in the literature, and (2) how have these practices been implemented and evaluated?

Recognizing the unique differences in how trauma is experienced and addressed across early childhood, later childhood, and adolescence (e.g., De Young, Kenardy, & Cobham, 2011), this review focused on one population: elementary-aged children (i.e., herein, children between the ages of 5 and 12). Although a review of trauma-focused services for each population would be beneficial, this population was selected as a starting point given that (a) young children are at highest risk of trauma exposure (Lieberman & Van Horn, 2009); (b) early intervention efforts are generally most effective at offsetting negative outcomes (e.g., Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000); and (c) the majority of related published articles have addressed elementary and secondary school settings rather than early childhood education (ECE) settings, such that fewer published articles on ECE implementation are available to synthesize (De Young et al., 2011). With growing attention (Overstreet & Chafouleas, 2016), guidance (Chafouleas et al., 2016), and provisions (NASP, 2016) for the implementation of trauma-focused practices in schools, this review offers a synthesis of the literature base at a critical juncture in the advancement of trauma-sensitive schools and, more broadly, the multidisciplinary field of school mental health.

Methods

Article Identification

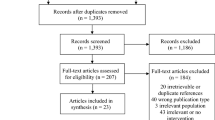

The first author identified articles through a three-stage, computerized search conducted in November 2016 (see Fig. 1). No publication date restrictions were put in place. The PsycINFO, ERIC, and PubMed databases were searched using the following Boolean phrases: trauma (“keyword” in PsycINFO, “subject term” in ERIC, “title/abstract” in PubMed) AND practice OR intervention OR treatment OR counseling (“keyword” in PsycINFO, “subject term” in ERIC, “title/abstract” in PubMed) AND school OR classroom (“all text” in PsycINFO, ERIC, and PubMed).

When available within each database, a series of filters assisted in narrowing articles according to participant age, publication type, and methodology. As depicted in Fig. 1, articles were considered for inclusion in the sample through a progressive review of the title, abstract, and full text to consider appropriateness with regard to the inclusion criteria. For the search’s second stage, an ancestral search of these articles was conducted by reviewing and considering articles cited on their reference lists (e.g., Kwon, Powelson, Wong, Ghali, & Conly, 2014). To reduce the likelihood of any articles being overlooked due to variability in indexing and keyword terms, in the third stage, all volumes and issues of two journals focused exclusively on mental health-related issues in schools (i.e., Advances in School Mental Health Promotion [2008–] and School Mental Health [2009–]) and of four journals focused more broadly on school psychology (i.e., Journal of School Psychology [1963–], Psychology in the Schools [1964–], School Psychology Review [1972–], School Psychology Quarterly [1986–]) were searched by conducting a keyword search for trauma on each journal’s publisher website.

The final article sample consisted of 39 articles, all of which met the following inclusionary criteria: (a) reported original, empirical, outcome data (b) on an intervention targeting prevention of or symptoms of psychological trauma (see Chafouleas et al., 2016) (c) implemented in a school setting (d) with children between the ages of 5 and 12 (i.e., approximating the ages of elementary students). Articles involving children outside the age range were included if children within the age range were also represented.

Data Extraction

To narratively describe the trauma-focused practices implemented within the identified articles, the authors extracted information including the intervention program name; source of trauma; number, ages, and gender of participants; the location of the study; intervention dosage; study methodologies; and outcomes. These data were compiled into a summary table.

Data Coding

To describe the implementation and evaluation of trauma-focused practices within the identified articles, the first author coded a range of variables. Coded variables included the methods used to identify intervention participants (none [i.e., universal delivery], referral, elevated ratings, diagnostic/classification criteria met); intensity of service delivery, per Chafouleas et al.’s (2016) conceptualization (low-intensity: strategies to promote adaptive skills and behaviors; intermediate-intensity: interventions providing psychoeducation regarding trauma and targeting social support systems and self-regulation skills; high-intensity: interventions designed “to remediate adverse effects and avoid re-traumatization” [Chafouleas et al., 2016, p. 149]); timing of service delivery (proactive, implemented due to known risk factors, reactive to known traumatic event)Footnote 2; intervention population(s) (student, school personnel, both); intervention agent(s) (teacher, other school-based professional, external clinician/researcher); setting (push-in, pull-out, extracurricular); treatment evaluation method (rating scale [self, teacher, other school-based professional, or family informant], direct observation, school records, interview, survey) and focus (constructs described in the authors’ language); reporting of effect sizes (yes, no); and reporting of treatment integrity (i.e., implemented as intended; Fabiano et al., 2014), treatment fidelity (i.e., implementation quality; Fabiano et al., 2014), acceptability, generalization, and maintenance data (i.e., evaluation of outcome 3 or more months post-intervention) (all yes, no). Operational definitions are available upon request.

Training on article coding included the authors discussing and finalizing the operational definitions, together coding a practice article, and independently coding additional practice articles (i.e., articles identified through the literature search that did not meet inclusionary criteria due to sample age) until they reached a percentage agreement exceeding 90% across variables for three consecutive articles. Following training procedures, the first author coded all (n = 39) articles, and the second and third authors independently coded a randomly selected, overlapping sample of 66.67% of the articles (n = 26 each), such that all articles were double-coded and 33.33% (n = 13) were triple-coded.

Percentage agreement was calculated for each coded variable; for the agreement of secondary coders with the primary coder, Cohen’s kappa coefficient was also calculated for each categorical coded variable with mutually exclusive categories (Kazdin, 1982). Agreement values averaged 91.52% (κ = .801, p < .001) across variables, ranging from 84.61% (intervention agent, measurement of generalization) to 100% (participant identification method) and from .594 (measurement of generalization) to .936 (measurement of treatment integrity). Overall agreement was 92.90% for one pair of coders (n = 26 articles), 89.94% for the second pair of coders (n = 26 articles), and 91.12% for all three coders (n = 13 articles). Disagreements were resolved by the authors re-reading the article and together agreeing upon the final code, such that all final agreement values were 100% (κ = 1.00).

Results

Trauma-Focused Intervention Practices

An overview of intervention populations, approaches, and outcomes is presented in supplementary online material, Table 1. Most procedures (for n = 30 studies, 76.92% of all studies) included cognitive behavioral therapeutic (CBT) approaches, with the Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) program being evaluated in 9 studies (23.08%) (with different populations and program adaptations). Other intervention strategies included therapeutic drama instruction (n = 1, 2.56%); eye movement desensitization and reprocessing training (n = 2, 5.13%); coping/social skill instructional or therapeutic practices not described as rooted in a CBT approach (n = 6, 15.38%); and comprehensive, multi-tiered systems that might encompass any of the previously identified strategies (n = 2, 5.13%).

Trauma-Focused Intervention Implementation

Interventions were implemented with student populations around the globe, with many targeting regions affected by political violence or natural disasters. Specifically, 57.50% of studies (n = 23) were conducted in North America (all in the USA); 25.00% (n = 10) were conducted in the Middle East (4 in Israel, 4 in Palestine, 1 in Lebanon, and 1 in Turkey); and 5.13% (n = 2) were conducted, respectively, in South America (2 in Argentina), Western Europe (1 in Denmark, 1 in the UK), and East Asia (1 in Indonesia, 1 in Sri Lanka). Studies conducted both within and outside the USA commonly referenced cultural considerations and adaptations in intervention design and implementation. Whereas some described intervention procedures developed specifically with a population’s culture and traumatic history in mind (e.g., Berger, Gelkopf, Heineberg, & Zimbardo, 2016, in political violence-afflicted Israel), others described researchers’ attempts to adapt existing intervention protocols for use within unique populations (e.g., Berger & Gelkopf, 2009, in post-tsunami Sri Lanka).

Reviewed articles contained a range of sample sizes and intervention designs. Specifically, samples ranged from 4 to 1488 participants (M = 207.23, SD = 301.74). Differences in sample sizes between intervention studies implemented within and outside the USA approached statistical significance [t(37) = 1.87, p = .06, d = .59], with a medium-sized effect (Cohen, 1988) for studies conducted abroad (n = 16) employing larger samples (M sample = 312.38, SDsample = 345.06) than those conducted in the USA (n = 23, M sample = 134.09, SDsample = 249.90). Sample size differences may be, at least in part, a function of differences in research designs. Although a higher percentage of US-based relative to international studies were randomized controlled trials (22.72% compared to 6.25%), a higher percentage of studies conducted abroad were cluster-randomized trials (50.00% compared to 18.18%), a quasi-experimental but often feasible approach for school-based research, and a smaller percentage of studies conducted abroad were limited pre-/post-treatment measurement designs (18.75% compared to 40.91%). Overall, the most common study designs were cluster-randomized trials and pre-/post-treatment measurement (for both, n = 12, 30.00%), followed by randomized controlled trials (n = 6, 15.00%), stratified-randomization trials and quasi-experimental convenience sampling (respectively, n = 4, 10.00%), and single-case designs (n = 3, 7.50%).

The majority (n = 36, 92.31%) of reviewed studies described high-intensity interventions focused on remediating adverse effects and avoiding re-traumatization. By contrast, one study described an intermediate-intensity intervention focused on psychoeducation and strengthening self-regulation and social support systems (Baum et al., 2013), and two described comprehensive interventions with supports of varying intensities (Beehler, Birman, & Campbell, 2012; Dorado, Martinez, McArthur, & Leibovitz, 2016). Notably, all reviewed studies conducted with international samples evaluated high-intensity interventions, compared to 86.96% of studies conducted within the USA. Overall, programs were described as most frequently implemented reactively in response to a community-wide traumatic event (e.g., natural disaster, political violence) (n = 24, 61.54%), with fewer studies reporting services being initiated due to known risk factors in the student population (e.g., suspected exposure to community violence in inner-city schools) (n = 12, 30.77%) or proactively in the absence of known exposure to trauma or risk factors for exposure (n = 3, 7.69%). For US-based studies, however, similar numbers of studies described service delivery as reactive (n = 7, 30.43% of US samples), implemented due to known risk factors (n = 9, 39.13% of US samples), or proactive (n = 7, 30.43% of US samples); reactive service delivery (n = 13, 81.25% of international samples) was much more common for international studies (implemented due to known risk factors, n = 3, 18.75% of international samples; proactive, n = 0).

In 15 studies (38.46%), intervention procedures were implemented universally, though this universal delivery was typically of high-intensity (n = 13, 86.67%), reactive (n = 11, 73.33%) services to student international samples (n = 12, 80%). More commonly, students were screened for participation (n = 23, 58.97%; for US samples, n = 19, 82.61%; for international samples, n = 4, 25.00%). Eligibility criteria consisted of elevated risk level indicated by rating scales (n = 18, 78.26% of studies employing screening), referral by school personnel (n = 5, 21.74%), and diagnostic criteria for PTSD being met (n = 2, 8.70%).

Most (n = 24, 61.54%) interventions solely included direct services to student populations (for US samples, n = 16, 69.57%; for international samples, n = 8, 50.00%). Four studies (10.26%), all international (25.00% of international studies), solely included indirect services in the form of school personnel training, and 11 (28.21%) included both direct and indirect services (for US samples, n = 7, 30.43%; for international samples, n = 4, 25.00%). For interventions involving direct services to students (n = 35), the majority (n = 26, 74.29%) required students to leave the typical classroom context to participate, whereas others were provided to students in their classrooms (n = 4, 11.43%), included multiple components in which students participated either within or outside the classroom context (n = 4, 1.43%), or were offered during extracurricular time in schools (n = 4, 11.43%). Pull-out interventions were most prevalent for both US (n = 17, 73.91% of US-based direct student services) and international samples (n = 6, 50.00% of international direct student services). Interventions with students were more often implemented by external clinicians or researchers (n = 19, 54.29%; for US samples, n = 11, 47.82% of US-based direct student services; for international samples, n = 8, 66.67% of international direct student services) relative to teachers (n = 4, 11.43%; for US samples, n = 1, 4.35% of US-based direct student services; for international samples, n = 3, 25.00% of international direct student services) and other school-based practitioners (n = 9, 25.71%; for US samples, n = 9, 39.13% of US-based direct student services; for international samples, n = 0), though two studies (5.71%) incorporated both external clinicians or researchers and school personnel as intervention agents.

Trauma-Focused Intervention Evaluation

Most studies (n = 34, 87.18%) reported positive treatment outcomes (typically, reduced symptoms of trauma and internalizing problems); however, only 10 (25.64%) reported accompanying effect sizes. Interventions were evaluated using multiple assessment methods (i.e., a combination of rating scales, interviews, observations, and/or record reviews) in just five studies (12.82%) and using multiple informants (e.g., student, teacher, family member, clinician) in 16 studies (41.03%). For US-based studies, five (21.74% of US samples) used multiple assessment methods, and 14 (60.87% of US samples) used multiple informants; no international studies employed multiple assessment methods, and few used multiple informants (n = 2, 12.50% of international samples). Overall, most (n = 37, 94.87%) studies employed rating scales, typically clinical ones that assessed the experience of symptoms related to trauma, depression, and anxiety. In fact, 33 studies (84.62%) reported only rating scale outcomes. Nearly all studies (n = 36, 92.31%) incorporated student self-report ratings, with ratings from parents in 10 studies (25.64%), teachers in seven studies (17.95%), and clinicians in one study (2.56%). Other evaluation methods included clinical interviews and review of school records (e.g., academic grades) (respectively, n = 3, 7.69%) as well as personnel surveys (n = 1, 2.56%).

Few studies formally assessed and reported treatment integrity (n = 8, 20.51%), treatment fidelity (n = 4, 10.26%), treatment acceptability (n = 9, 23.08%), and generalization across settings (n = 10, 25.64%). US-based studies were more likely to report these types of data relative to international studies (i.e., for USA relative to international samples, 26.09% compared to 12.50% reported treatment integrity, 17.39% compared to 0% reported treatment fidelity, 39.13% compared to 0% reported treatment acceptability, and 34.78% compared to 12.50% reported cross-setting generalization). Of all studies reporting generalization data, five (50%) described outcomes for different settings within the school system (e.g., in classrooms when the intervention was provided in a pull-out counseling setting), four (40%) reported outcomes for settings outside the school system (i.e., home in all cases), and one (10%) reported outcomes for both within- and across-system setting generalization.

Relative to these measurement variables, a higher percentage of studies (46.15%, n = 18) reported maintenance data collected at least 3 months following the termination of services, with the duration of follow-up data collection ranging from 3 to 36 months (M = 7.56, SD = 7.81). Maintenance data were more often reported for international samples (n = 10, 62.5% of international studies) than for US samples (n = 8, 34.78% of US-based studies), though durations of follow-up data collection were similar between groups [t(16) = .26, p = .80] (in months, for international studies, M = 8.00, SD = 10.23; for US studies, M = 7.00, SD = 3.59).

Discussion

This review synthesizes 39 studies evaluating the school-based implementation of trauma-focused practices with elementary student populations. These studies spanned ranges of geographic locations, cultures, and types of trauma. Most reviewed interventions were high-intensity ones implemented in response to commonly experienced traumatic events (e.g., natural disaster, political violence), in pull-out settings, and by external clinicians or researchers. Further, most interventions were evaluated using clinical rating scales and without consideration of important dimensions such as treatment integrity, fidelity, and acceptability as well as outcome generalization and maintenance. Together, these findings have informed the following recommendations regarding integrating trauma-focused practices within existing multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) as well as designing methods of intervention delivery and assessment.

Integration Within MTSS

In the current review, most reviewed articles described high-intensity, reactive interventions implemented with students demonstrating significant, if not clinical-level, post-traumatic stress-related symptoms. With this focus on interventions for select populations, it may be less clear what lower-intensity trauma-focused practices look like; however, there is a vast literature base that may inform implementation in this area: that of school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports (SWPBIS). “Build[ing] positive adaptive systems” (Chafouleas et al., 2016, p. 149) by targeting school climate and students’ social problem-solving abilities, coping skills, and growth mindset may be commonly fostered by SWPBIS strategies. For example, the SWPBIS tier-1 strategies of setting school-wide behavioral expectations and consistently responding to students’ positive and problem behaviors may create predictable environments in which students feel safe, secure, and supported (e.g., Sprick, 2009). Additionally, explicit skill instruction strategies commonly implemented to targeted populations within SWPBIS (e.g., targeting social, coping, anger management, conflict resolution, or relaxation skills) may enhance students’ abilities to cope with and recover from trauma, whereas targeted SWPBIS strategies that connect students with faculty mentors (e.g., check-in/check-out and mentoring procedures) may provide opportunities for students to build meaningful relationships with supportive adults.

Due to the seemingly artificial distinction currently being cast between the strategies shared by SWPBIS and trauma-informed approaches, school practitioners and administrators alike might be discouraged by the idea of implementing “yet another” multi-tiered system within their schools. Embedding trauma-focused practices within existing MTSS may be a feasible, efficient, and effective way of promoting students’ mental health and school success. It may, however, be challenging to implement trauma-focused practices without the buy-in of school personnel. For example, teachers have been found to be most supportive of trauma-focused practices when they perceive a need for services, and they commonly struggle with the competing priorities of addressing students’ social-emotional and academic needs (Baweja et al., 2016). Thus, it is often necessary to establish a strong rationale for investing time and resources into trauma-focused practices as well as install systems-level supports to assist school practitioners in implementing these practices with integrity and fidelity. Fortunately, a range of resources are available to guide practitioners in disseminating information regarding trauma-informed approaches and advocating for their school-based implementation (see Bell, Limberg, & Robinson, 2013; Cole et al., 2013).

Intervention Delivery

With students from many geographic regions and cultures represented in the current review, we are reminded of trauma being a global issue that, in many cases, can be effectively remediated using culturally sensitive practices. This necessitates the development and/or adaptation of trauma-focused practices that appropriately address, for example, the linguistic, interpersonal, and spiritual/religious diversity of student populations both within and beyond the USA. For example, within the USA, three articles reporting the effects of interventions conducted in rural schools with American Indian students (Goodkind, LaNoue, & Milford, 2010; Morsette, Swaney, Stolle, Schuldberg, van den Pol, & Young, 2009; Morsette, van den Pol, Schuldberg, Swaney, & Stolle, 2012) detail means by which researchers adapted the CBITS protocol, originally designed for use with ethnically diverse students in urban settings, to better fit within this population’s unique culture and, specifically, religion.

Analyzing the article sample by study location and student population reveals subgroups of students for whom little trauma-focused intervention research has been conducted. For instance, although several studies have worked with American Indian children in rural, southwestern American, reservation communities, fewer studies have examined means of supporting rural American children from non-Indian American backgrounds. Most research conducted in the USA has focused upon urban, particularly inner-city populations (e.g., from Los Angeles, Chicago, New Orleans), whose needs, experiences of trauma, and cultural backgrounds may differ significantly from rural populations. Additionally, most US-based and international research has examined exposure to types of trauma that are largely visible, such as effects from natural disasters, political violence, and community violence (e.g., in high-risk, inner-city neighborhoods). We know much less about trauma that is often more covert, such as resulting from domestic (or otherwise interpersonal) physical or sexual violence, chronic illness of one’s self or a loved one, and death of a loved one. Further, we know much less about the effectiveness of school-based treatment for chronic, as opposed to more isolated, exposure to trauma. These limitations point to the need for continued intervention development and research.

The most typical trauma-focused intervention in the reviewed literature incorporated largely reactive, direct services to students provided by external clinicians or researchers. This intervention characterization was more often the case in international samples, where large-scale natural or political disasters typically predicated service delivery, drawing the attention and support of researchers or clinicians who would lead school-based intervention efforts. Increasingly, however, in the USA as well as abroad, school personnel appear to be targeted in practices aimed at enhancing schools’ capacities to provide trauma-focused practices, both in the reviewed literature (e.g., Dorado et al., 2016) and in the broader national/global context (e.g., NASP, 2016). Targeting school practitioners’ knowledge of trauma, its effects, and methods of supporting students who have experienced trauma may facilitate their identification of students in need of services, enabling more proactive service delivery, as well as equip them in becoming viable intervention agents. Addressing student challenges early in their emergence might lead to lower-intensity services being required, ultimately leading to less missed instructional time and less strain on school practitioner time and resources. Although implementation by external clinicians and researchers can be beneficial in building a system’s capacity to address needs, student outcomes may differentially improve and sustain when interventions are implemented by school personnel with whom students have consistent contact.

Assessment

In the reviewed literature, participant identification and treatment evaluation practices typically strayed from a multi-method, multi-informant approach, relying predominantly on rating scale methods that, in many cases, depended upon the report of a single stakeholder (typically the student). Employing additional assessment methods (e.g., observations, record review) and including the perspectives of additional stakeholders (e.g., school personnel, family members) may heighten the accuracy and utility of resulting data used for decision-making.

Additionally, the employed rating scales were generally narrow-band clinical ones assessing psychopathological symptoms. As Chafouleas and colleagues (2016) note, this deficiency-based assessment approach may restrict our understanding of trauma’s emotional, behavioral, social, and academic implications. By focusing also or instead on assessing factors of resilience (e.g., self-regulation, self-efficacy), we may better understand the social significance of intervention outcomes as well as detect more subtle changes. In many cases, too, school practitioners have access to a limited supply of assessment tools and a limited budget with which to purchase additional ones, such that the utility of existing screening tools and rating scales typically available in schools should be considered. In addition to internalizing and externalizing composites on broadband scales often used in schools, instruments focusing on prosocial skills may be useful in the context of participant identification and intervention evaluation, as well as in informing intervention selection and design.

Moreover, it is discouraging that the reviewed literature, and particularly international studies, infrequently reported important components of treatment evaluation. Understanding the extent to which interventions are implemented as intended (treatment integrity) and with high quality (treatment fidelity) helps clarify whether outcomes are attributable to the manualized intervention procedures and indicates procedural feasibility or the need for modifications and external implementation supports. Similarly, assessment of treatment acceptability may point to necessary modifications to ease or otherwise improve implementation. Further, given schools’ provision of access to students and wealth of information on students, it is surprising that more studies did not report maintenance of intervention outcomes and outcome generalization. Barring student mobility, school is well equipped to measure both short- and long-term outcomes of trauma-focused practices. Schools also routinely collect data that might be used to assess outcome generalization beyond reduction in internalizing symptoms (e.g., improvements in attendance, academic performance, and social interactions; reductions in school nurse visits). Thus, it is advised that school practitioners leverage available school records and systems in thoroughly evaluating trauma-focused practices with respect to treatment integrity, fidelity, acceptability and outcome maintenance and generalization.

Recommendations for Future Research and Practice

The reported effectiveness of most reviewed studies indicates the importance of widespread adoption of school-based, trauma-focused practices, though future research should strive to employ rigorous experimental designs and adequate sample sizes as well as consistently report effect sizes to clarify treatment outcomes. Additional research is needed to clarify what factors related to children’s experience of trauma are most malleable (i.e., intervention targets), for what populations (i.e., moderators), and through what mechanisms (e.g., mediators); such research is expected to provide further guidance to practitioners looking to maximize the acceptability, fit, and effectiveness of trauma-focused practices within their schools. Moreover, developments in screening tools and rating scales that specifically assess trauma-related symptoms or resilience factors and are designed for administration in school populations may be particularly useful in advancing identification and progress monitoring practices. Similarly, developments in methods to (a) increase school personnel buy-in (e.g., [pre-]professional development, trainings) and (b) support school practitioners in implementing trauma-focused practices (e.g., coaching, performance feedback) may also heighten treatment integrity, fidelity, acceptability, and effectiveness. Future intervention evaluation research should include direct measurement of each of these dimensions as well as report outcome generalization and maintenance to not only thoroughly evaluate practices but also provide clear, replicable models of implementation and evaluation.

The following specific recommendations are made regarding the delivery of trauma-focused practices at varying intensities.

Low-Intensity Supports: Building Positive Adaptive Systems

Likely, a broad array of existing, low-intensity SWPBIS strategies may be implemented within multi-tiered systems of trauma-informed care with promising results on the outcome of adaptive skill development. Narratively reviewing the broad SWPBIS literature base in tandem with the current study’s article sample was largely unfeasible, and few low-intensity trauma-focused practices were identified using search and inclusion criteria because such practices have not been commonly described in the literature as supporting trauma-related resilience. Identified low-intensity trauma-focused supports included strategies provided at the levels of students (e.g., classroom-based coping skills instruction), adults (e.g., staff and parent workshops on coping with stress), and systems (e.g., consultation within trauma-informed framework) (Dorado et al., 2016). Given the likely availability of additional low-intensity supports that may be integrated within trauma-informed service delivery frameworks, researchers are encouraged to both evaluate and, in dissemination, highlight the utility of these strategies on trauma-related outcomes; practitioners are encouraged to identify components of SWPBIS and consider how such components may be applied and, possibly, augmented in the service of trauma prevention.

Intermediate-Intensity Supports: Providing Psychoeducation on Trauma and Targeting Social Support and Self-Regulatory Systems

As with other MTSS (e.g., Stormont & Reinke, 2013), trauma-focused strategies of intermediate intensity (e.g., at Tier 2) may receive less attention compared to universal prevention and high-need intervention efforts. In the current review, identified intermediate-intensity supports were provided to students (e.g., psychoeducation on trauma, skill-building workshops), adults (e.g., wellness groups for school staff, coordinated care teams for families), as well as systems (e.g., hiring of culture brokers to facilitate relationship-building and outreach services, ongoing review and revision of discipline policies and procedures) (Baum et al., 2013; Beehler et al., 2012; Dorado et al., 2016). Given that, within a multi-tiered system, supports of this intensity are to be delivered to more students than high-intensity supports, these strategies must be efficient and feasible to implement. Future research may focus not only on the development and evaluation of intermediate-intensity trauma-focused practices but also on issues related to their sustained implementation and effectiveness in preventing students from needing higher intensity supports. Additionally, assessment methods should be evaluated in terms of their sensitivity and specificity for identifying students in need of more intensive supports. Practitioners aiming to bolster their schools’ capacity to deliver intermediate-intensity supports are encouraged to contact community agencies and programs to identify means by which students’ social support needs may be met outside of school hours and beyond the school year.

High-Intensity Supports: Remediating Adverse Effects and Avoiding Re-traumatization

The current review is most informative in terms of what high-intensity trauma-focused supports in schools look like (e.g., commonly CBT approaches) and how they are implemented (e.g., typically by external researchers or clinicians in pull-out settings) and evaluated (e.g., typically using self-reported ratings). Yet additional research at this level of trauma-focused support intensity is particularly needed for the previously identified subgroups of students for whom intervention research is lacking, notably students whose trauma has not resulted from community-wide disasters and, in the USA, for students residing in rural and suburban areas. There is a clear need for the development or adaptation of high-intensity trauma-focused interventions to appropriately address the diverse needs of students from various cultures around the world as well as for the design of implementation supports to make such high-intensity services feasible and acceptable to implement by practitioners in school settings.

Limitations of the Review

As previously described, the current review focuses on elementary populations, such that its findings may not generalize to early childhood and secondary populations. Additional critical reviews are needed to synthesize these corresponding literature bases and, thereby, identify considerations for future practice and research. Further, although multi-step search procedures were adopted to reduce the number of omitted articles, additional articles meeting inclusion criteria may have been overlooked due to the search indices and terms, databases, or journals selected for the search process (Kwon et al., 2014). Moreover, this review only included empirical studies published in peer-reviewed journals, and as of November 2016. Intervention evaluation efforts not published in this literature may systematically differ from included articles on factors such as practice components and effectiveness (see Weisz, Doss, & Hawley, 2005). For example, uncontrolled case studies of trauma-focused practices disseminated on private websites (e.g., https://acestoohigh.com) (Overstreet & Chafouleas, 2016) were not included in this review. Given widespread attention to trauma-sensitive schools during the time of this review (e.g., following ESSA’s passage in December 2015), the article sample might exclude important practical findings currently being discovered or awaiting to be published.

Conclusions

The extant literature base provides preliminary support for the adoption of trauma-informed approaches within schools. The school-based implementation of trauma-focused practices might reach the most students and lead to the most positive and sustainable outcomes when such services are embedded within SWPBIS and integrated MTSS models; when service delivery is culturally sensitive as well as expanded and enriched through school personnel training; and when screening and intervention evaluation foci, methods, and informants are broadened. Integrated research and practice agendas are needed to better clarify methods of effective and durable school-based implementation.

Notes

Herein, we will use trauma-informed approach to refer to the general framework of service delivery as described by SAMHSA (2014), and trauma-focused practices to refer to specific interventions designed to prevent trauma or address responses to trauma and promote resilience.

Note that our coding procedures do not include classification of “tier.” Although we recognize the commonality for the multi-tiered systems of support literature to describe, for example, a behavioral strategy as “tier-1” or a reading intervention as “tier-2,” we also recognize the extent to which one’s environment could affect the delivery of trauma-focused practices at varying intensities to universal, targeted, and select populations (Sugai, Horner, & Gresham, 2002); that is, we acknowledge the potential for contextual specificity of “tiers” and find it challenging to generalize school systems’ approaches to multi-tiered trauma-informed care across contexts of variable trauma prevalence. For example, a group cognitive-behavioral therapeutic intervention might be considered a tier-1 intervention in a post-crisis environment (when delivered universally) but might be considered a tier-3 intervention in a school that has not recently been affected by a community-wide crisis (when delivered to select students; e.g., those referred or identified with elevated behavior ratings). Accordingly, to more precisely characterize the reviewed trauma-focused practices, we specifically describe the breadth (i.e., method of participant identification), intensity, and timing of service delivery, which readers may use to evaluate such practices’ relevance to their school populations’ needs. In moving toward consensus on trauma-informed service delivery in schools, Chafouleas et al. (2016) have provided an exemplary multi-tiered model of trauma-informed care (see pp. 148–149) from which we have adopted our operationalizations for the three levels of service intensities. Thus, readers embracing the service delivery approach advocated by Chafouleas et al. may choose to interpret our use of “service intensity” as a proxy for tier.

References

*Denotes article included in review.

*Aduriz, M. E., Bluthgen, C., & Knopfler, C. (2009a). Helping child flood victims using group EMDR intervention in Argentina: Treatment outcome and gender difference. International Journal of Stress Management, 16, 138–153. doi:10.1037/a0014719.

*Aduriz, M. E., Bluthgen, C., & Knopfler, C. (2009b). Helping child flood victims using group EMDR intervention in Argentina: Treatment outcome and gender difference. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 1, 58–67. doi:10.1037/a0014719.

*Amaya-Jackson, L., Reynolds, V., Murray, M. C., McCarthy, G., Nelson, A., Cherney, M. S., et al. (2003). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder: Protocol and application in school and community settings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 10, 204–213. doi:10.1016/S1077-7229(03)80032-9.

*Baum, N. L., Cardozo, B. L., Pat-Horenczyk, R., Ziv, Y., Blanton, C., Reza, A., et al. (2013). Training teachers to build resilience in children in the aftermath of war: A cluster randomized trial. Child and Youth Care Forum, 42, 339–350. doi:10.1007/s10566-013-9202-5.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews. Review of General Psychology, 1, 311–320. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.1.3.311.

Baweja, S., Santiago, C. D., Vona, P., Pears, G., Langley, A., & Kataoka, S. (2016). Improving implementation of a school-based program for traumatized students: Identifying factors that promote teacher support and collaboration. School Mental Health, 8, 120–131. doi:10.1007/s12310-015-9170-z.

*Beehler, S., Birman, D., & Campbell, R. (2012). The effectiveness of Cultural Adjustment and Trauma Services (CATS): Generating practice-based evidence on a comprehensive, school-based mental health intervention for immigrant youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50, 155–168. doi:10.1007/s10464-011-9486-2.

Bell, H., Limberg, D., & Robinson, E. (2013). Recognizing trauma in the classroom: A practical guide for educators. Childhood Education, 89, 139–145. doi:10.1080/00094056.2013.792629.

*Berger, R., & Gelkopf, M. (2009). School-based interventions for the treatment of tsunami-related distress in children: A quasi-randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78, 364–371. doi:10.1159/000235976.

*Berger, R., Gelkopf, M., Heineberg, Y., & Zimbardo, P. (2016). A school-based intervention for reducing posttraumatic symptomatology and intolerance during political violence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108, 761–771. doi:10.1037/edu0000066.

*Berger, R., Pat-Horenczyk, R., & Gelkopf, M. (2007). School-based intervention for prevention and treatment of elementary-students’ terror-related distress in Israel: A quasi-randomized controlled trial. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20, 541–551. doi:10.1002/jts.20225.

Birur, B., Moore, N. C., & Davis, L. L. (2017). An evidence-based review of early intervention and prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder. Community Mental Health Journal, 53, 183–201. doi:10.1007/s10597-016-0047-x.

*Brown, E. J., McQuaid, J., Farina, L., Ali, R., & Winnick-Gelles, A. (2006). Matching interventions to children’s mental health needs: Feasibility and acceptability of a pilot school-based trauma intervention program. Education and Treatment of Children, 29, 257–286.

*Carrion, V. G., & Hull, K. (2009). Treatment manual for trauma-exposed youth: Case studies. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 15, 27–38. doi:10.1177/1359104509338150.

Chafouleas, S. M., Johnson, A. H., Overstreet, S., & Santos, N. M. (2016). Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. School Mental Health, 8, 144–162. doi:10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8.

*Chemtob, C. M., Nakashima, J. P., & Hamada, R. S. (2002). Psychosocial intervention for postdisaster trauma symptoms in elementary school children: A controlled community field study. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 156, 211–216. doi:10.1001/archpedi.156.3.211.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cole, S. F., Eisner, A. E., Gregory, M., & Ristuccia, J. (2013). Creating and advocating for trauma-sensitive schools. Boston: Massachusetts Advocates for Children.

De Young, A. C., Kenardy, J. A., & Cobham, V. E. (2011). Trauma in early childhood: A neglected population. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 231–250. doi:10.1007/s10567-011-0094-3.

*Diab, M., Peltonen, K., Qouta, S. R., Palosaari, E., & Punamaki, R.-L. (2015). Effectiveness of psychosocial intervention enhancing resilience among war-affected children and the moderating role of family factors. Child Abuse and Neglect, 40, 24–35. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.12.002.

*Dorado, J. S., Martinez, M., McArthur, L. E., & Leibovitz, T. (2016). Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools (HEARTS): A whole-school, multi-level, prevention and intervention program for creating trauma-informed, safe and supportive schools. School Mental Health, 8, 163–176. doi:10.1007/s12310-016-9177-0.

*Ehntholt, K. A., Smith, P. A., & Yule, W. (2005). School-based cognitive-behavioral therapy group intervention for refugee children who have experienced war-related trauma. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 10, 235–250. doi:10.1177/1359104505051214.

Fabiano, G. A., Chafouleas, S. M., Weist, M. D., Sumi, W. C., & Humphrey, N. (2014). Methodology considerations in school mental health research. School Mental Health, 6, 68–83. doi:10.1007/s12310-013-9117-1.

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H. A., Shattuck, A., & Hamby, S. L. (2015). Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: Results from the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics, 169, 746–754. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676.

*Goodkind, J. R., LaNoue, M. D., & Milford, J. (2010). Adaptation and implementation of cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools with American Indian youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39, 858–872. doi:10.1080/15374416.2010.517166.

*Jaycox, L. H., Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., Walker, D. W., Langley, A. K., Gegenheimer, K. L., et al. (2010). Children’s mental health care following Hurricane Katrina: A field trial of trauma-focused psychotherapies. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23, 223–231. doi:10.1002/jts.20518.

*Jaycox, L. H., Langley, A. K., Stein, B. D., Wong, M., Sharma, P., Scott, M., et al. (2009). Support for students exposed to trauma: A pilot study. School Mental Health, 1, 49–60. doi:10.1007/s12310-009-9007-8.

*Karam, E. G., Fayyad, J., Karam, A. N., Tabet, C. C., Melhem, N., Mneimneh, Z., et al. (2008). Effectiveness and specificity of a classroom-based group intervention in children and adolescents exposed to war in Lebanon. World Psychiatry, 7, 103–109. doi:10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00170.x.

*Kataoka, S., Jaycox, L. H., Wong, M., Nadeem, E., Langley, A., Tang, L., et al. (2011). Effects on school outcomes in low-income minority youth: Preliminary findings from a community-partnered study of a school trauma intervention. Ethnicity and Disease, 21, S1-71–S1-77.

*Kataoka, S. H., Stein, B. D., Jaycox, L. H., Wong, M., Escudero, P., Tu, W., et al. (2003). A school-based mental health program for traumatized Latino immigrant children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 311–318. doi:10.1097/01.CHI.0000037038.04952.8E.

Kazdin, A. E. (1982). Single-case research designs: Methods for clinical and applied settings. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kwon, Y., Powelson, S. E., Wong, H., Ghali, W. A., & Conly, J. M. (2014). An assessment of the efficacy of searching in biomedical databases beyond MEDLINE in identifying studies for a systematic review on ward closures as an infection control intervention to control outbreaks. Systematic Reviews, 3, 135. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-135.

Lieberman, A. F., & Van Horn, P. (2009). Giving voice to the unsayable: Repairing the effects of trauma in infancy and early childhood. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 18, 707–720. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2009.02.007.

Little, S. G., & Akin-Little, A. (2013). Trauma in children: A call to action in school psychology. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 29, 375–388. doi:10.1080/15377903.2012.695769.

*March, J., Amaya-Jackson, L., Murray, M., & Schulte, A. (1998). Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for children and adolescents with post-traumatic stress disorder after a single incident stressor. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 585–593. doi:10.1097/00004583-199806000-00008.

*Morsette, A., Swaney, G., Stolle, D., Schuldberg, D., van den Pol, R., & Young, M. (2009). Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS): School-based treatment on a rural American Indian reservation. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 40, 169–178. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2008.07.006.

*Morsette, A., van den Pol, R., Schuldberg, D., Swaney, G., & Stolle, D. (2012). Cognitive behavioral treatment for trauma symptoms in American Indian youth: Preliminary findings and issues in evidence-based practice and reservation culture. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 5, 51–62. doi:10.1080/1754730X.2012.664865.

National Association of School Psychologists (NASP). (2016). The Every Student Succeeds Act: Details of the new law. Retrieved from https://www.nasponline.org/research-and-policy/current-law-and-policy-priorities/policy-priorities/the-every-student-succeeds-act/details-of-essa.

Overstreet, S., & Chafouleas, S. M. (2016). Trauma-informed schools: Introduction to the special issue. School Mental Health, 8, 1–6. doi:10.1007/s12310-016-9184-1.

Overstreet, S., & Mathews, T. (2011). Challenges associated with exposure to chronic trauma: Using a public health framework to foster resilient outcomes among youth. Psychology in the Schools, 48, 738–754. doi:10.1002/pits.20584.

Perfect, M. M., Turley, M. R., Carlson, J. S., Yohanna, J., & Saint Gilles, M. P. (2016). School-related outcomes of traumatic event exposure and traumatic stress symptoms in students: A systematic review of research from 1990 to 2015. School Mental Health, 8, 7–43. doi:10.1007/s12310-016-9175-2.

Porche, M. V., Costello, D. M., & Rosen-Reynoso, M. (2016). Adverse family experiences, child mental health, and educational outcomes for a national sample of students. School Mental Health, 8, 44–60. doi:10.1007/s12310-016-9174-3.

*Powell, T. M., & Bui, T. (2016). Supporting social and emotional skills after a disaster: Findings from a mixed method study. School Mental Health, 8, 106–119. doi:10.1007/s12310-016-9180-5.

*Punamäki, R.-L., Peltonen, K., Diab, M., & Qouta, S. R. (2014). Psychosocial interventions and emotion regulation among war-affected children: Randomized control trial effects. Traumatology, 20, 241–252. doi:10.1037/h0099856.

*Qouta, S. R., Peltonen, K., Diab, S. Y., Anttila, S., Palosaari, E., & Punamäki, R.-L. (2016). Psychosocial intervention and dreaming among war-affected Palestinian children. Dreaming, 26, 95–118. doi:10.1037/drm0000025.

Rolfsnes, E. S., & Idsoe, T. (2011). School-based intervention programs for PTSD symptoms: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24, 155–165. doi:10.1002/jts.20622.

*Ronholt, S., Karsberg, S., & Elklit, A. (2013). Preliminary evidence for a classroom based psychosocial intervention for disaster exposed children with posttraumatic stress symptomatology. Child and Youth Care Forum, 42, 617–631. doi:10.1007/s10566-013-9220-3.

*Salloum, A., & Overstreet, S. (2008). Evaluation of individual and group grief and trauma interventions for children post disaster. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 37, 495–507. doi:10.1080/15374410802148194.

*Salloum, A., & Overstreet, S. (2012). Grief and trauma intervention for children after disaster: Exploring coping skills versus trauma narration. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50, 169–179. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2012.01.001.

*Saltzman, W. R., Pynoos, R. S., Layne, C. M., Steinberg, A. M., & Aisenberg, E. (2001). Trauma- and grief-focused intervention for adolescents exposed to community violence: Results of a school-based screening and group treatment protocol. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5, 291–303. doi:10.1037//1089-2699.5.4.291.

*Santiago, C. D., Kataoka, S. H., Hu-Cordova, M., Alvarado-Goldberg, K., Maher, L. M., & Escudero, P. (2015). Preliminary evaluation of a family treatment component to augment a school-based intervention serving low-income families. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 23, 28–39. doi:10.1177/1063426613503497.

*Santiago, C. D., Lennon, J. M., Fuller, A. K., Brewer, S. K., & Kataoka, S. H. (2014). Examining the impact of a family treatment component for CBITS: When and for whom is it helpful? Journal of Family Psychology, 28, 560–570. doi:10.1037/a0037329.

Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. (Eds.). (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early child development. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

*Sklarew, B., Krupnick, J., Ward-Wimmer, D., & Napoli, C. (2002). The school-based mourning project: A preventive intervention in the cycle of inner-city violence. Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 4, 317–330. doi:10.1023/A:1015777428039.

Sprick, R. (2009). CHAMPS: A proactive and positive approach to classroom management (2nd ed.). Eugene, OR: Pacific Northwest Publishing.

*Stein, B. D., Jaycox, L. H., Kataoka, S. H., Wong, M., Tu, W., Elliott, M. N., et al. (2003). A mental health intervention for schoolchildren exposed to violence: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 290, 603–611. doi:10.1001/jama.290.5.603.

Stormont, M., & Reinke, W. M. (2013). Implementing tier 2 social behavioral interventions: Current issues, challenges, and promising approaches. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 29, 121–125. doi:10.1080/15377903.2013.778769.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Sugai, G., Horner, R. H., & Gresham, F. M. (2002). Behaviorally effective school environments. In M. R. Shinn, H. M. Walker, & G. Stoner (Eds.), Interventions for academic and behavior problems II: Preventive and remedial approaches (pp. 315–350). Washington, DC: National Association of School Psychologists.

Sullivan, A. L., & Simonson, G. R. (2016). A systematic review of school-based social-emotional interventions for refugee and war-traumatized youth. Review of Educational Research, 8, 503–530. doi:10.3102/0034654315609419.

*Thabet, A. A., Vostanis, P., & Karim, K. (2005). Group crisis intervention for children during ongoing war conflict. European Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 14, 262–269. doi:10.1007/s00787-005-0466-7.

*Tol, W. A., Komproe, I. H., Susanty, D., Jordans, M. J. D., Macy, R. D., & De Jong, J. T. V. M. (2008). School-based mental health intervention for children affected by political violence in Indonesia: A cluster randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 300, 655–662. doi:10.1001/jama.300.6.655.

Weisz, J. R., Doss, A. J., & Hawley, K. M. (2005). Youth psychotherapy outcome research: A review and critique of the evidence base. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 337–363. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141449.

*Whitson, M. L., Bernard, S., & Kaufman, J. S. (2015). The mediating role of parenting stress for children exposed to trauma: Results from a school-based system of care. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1141–1151. doi:10.1007/s10826-014-9922-7.

*Wolmer, L., Hamiel, D., & Laor, N. (2011). Preventing children’s posttraumatic stress after disaster with teacher-based intervention: A controlled study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 340–348. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2011.01.002.

*Wolmer, L., Laor, N., Dedeoglu, C., Siev, J., & Yazgan, Y. (2005). Teacher-mediated intervention after disaster: A controlled three-year follow-up of children’s functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 1161–1168. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00416.x.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors, such that informed consent requirements do not apply to study procedures.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zakszeski, B.N., Ventresco, N.E. & Jaffe, A.R. Promoting Resilience Through Trauma-Focused Practices: A Critical Review of School-Based Implementation. School Mental Health 9, 310–321 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-017-9228-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-017-9228-1