Abstract

As we reported in the previous two articles in this series, the U.S. military has actively attempted to deal with its mental health dilemma by utilizing 10 approaches. These strategies function to help the military avoid learning its war trauma lessons to the contrary, and it appears that their approach is to prevent or reduce mass psychiatric attrition and exorbitant costs associated with psychiatric treatment and disability pensions, to the clear detriment of its fighting force and their families denied adequate mental healthcare. In this final review, we examine the remaining five harmful approaches designed to prevent the so-called evacuation syndromes that the military worries might arise should psychiatric lessons of war ever be implemented, such as eliminating stigma and elevating mental health services on par with medical services. The five avoidance strategies we cover include (6) delay, deception, and delay; (7) faulty diagnosis and “backdoor” discharges; (8) maintaining diffusion of responsibility and unaccountability; (9) provision of inadequate, experimental, or harmful treatment; and (10) perpetuating neglect, indifference, and self-inflicted crises. We conclude our analysis by asserting that the U.S. military has tried every conceivable way to unburden itself from the psychological realities of modern warfare, with the notable exception of actually committing to learning its war trauma lessons and genuinely implementing the required policies for good.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The time for action is now. The human and financial costs of un-addressed problems will rise dramatically over time. Our nation learned this lesson, at a tragic cost, in the years following the Vietnam War. Fully investing in prevention, early intervention, and effective treatment are responsibilities incumbent upon us as we endeavor to fulfill our obligation to our military service members (Department of Defense Task Force on Mental Health, 2007, p. 63).

Introduction

It appears that the military has never genuinely learned its lesson when it comes to managing its mental health dilemma (Russell, Schaubel, & Figley, 2017a, b). Instead, military and government leaders repeatedly ignore the simplest and most basic war trauma lessons, such as the need to prepare for inevitable large numbers of psychiatric casualties, which has been the case for that every cohort since the First World War (WWI) (e.g., Russell, Figley, & Robertson, 2015). Today, the passive avoidance of learning war trauma lessons was painfully illuminated by the U.S. Army’s senior psychiatrist’s candid admission that, during the 2003 Iraq invasion planning, “Mental health was not a welcomed topic… we were not allowed to speak of the unseen wounds of war… we were not allowed to prepare for the invisible wounds” (Brigadier General Lori Sutton, U.S. Army; Sutton, 2016). One hundred years earlier, General Sutton’s WWI counterpart warned that prior to the American entry into the Great War, there is:

The next most important lesson is that of preparing, in advance of an urgent need, a comprehensive plan for establishing special military hospitals and using existing civil facilities for treating mental disease in a manner that will serve the army effectively and at the same time safeguard the interests of the soldiers, of the government and of the community (Salmon, 1917, p. 28).

Willful negligence of 100 years of lessons learned after every subsequent American war helps to explain the DoD’s Task Force on Mental Health (DoD TF-MH, 2007) conclusion: “A single finding underpinning all others: The Military Health System lacks the fiscal resources and the fully trained personnel to fulfill its mission to support psychological health in PEACETIME or fulfill the enhanced requirements imposed during times of conflict” (p. ES.2). This systematic lack has been perpetuating a generational cycle of preventable and self-inflicted wartime behavioral health crises since WWI (Russell & Figley, 2015a, b; Russell, Zinn, & Figley, 2016).

As we reported in the previous two articles in this series, the military has actively attempted to deal with its mental health problem by utilizing 10 strategies intended to avoid psychiatric attrition, treatment, and disability pensions to the detriment of millions of its soldiers (Russell et al., 2017a, b). We have already reviewed in depth the first five of the strategies in the second article of our series. In this final article, we examine the remaining five harmful approaches designed to prevent evacuation syndromes that the military worries could inevitably arise should psychiatric lessons of war ever be implemented, such as eliminating stigma and elevating mental health services on par with medical services (Russell et al., 2017a). The five avoidance strategies we will cover include (6) delay, deception, and delay; (7) faulty diagnosis and “backdoor” discharges; (8) maintaining diffusion of responsibility and unaccountability; (9) provision of inadequate, experimental, or harmful treatment; and (10) perpetuating neglect, indifference, and self-inflicted crises.

Strategy 6: Delay, Deception, and Delay

The ability of the military to accomplish its mission to fight and win wars requires not only defeating adversaries on the battlefield but also winning public support at home. Since WWI, the military has been embroiled in national controversies regarding large numbers of returning war veterans with unmet mental health needs and skyrocketing pension costs that either threaten or serve to erode public support (Russell & Figley, 2017a). Consequently, the military has been forced to develop public relations (PR) campaigns designed to manage the mental health narrative in a manner that sustains public backing long enough to win the current war. Managing or manipulating the public narrative is yet another example of an overarching strategy to avoid dealing with the psychological realities of war. The PR mission is accomplished via the avoidance strategy of delay, deceive, and delay in three, sometimes overlapping stages: (1) avoiding disclosure or recognition of wartime mental health needs or crisis via publicity blackouts; (2) public deception through narrative filters and designed to deny the existence and/or scope of a mental health crisis, typically in response to external inquiries; and (3) delaying full commitment and implementation of externally mandated changes by engaging in tactical appeasement, half-measures, or other forms of partial compliance.

Avoiding Public Disclosure of Recognition of Mental Health Needs

Transparency about the size, scope, and costs of wartime mental health needs will inevitably result in serious public questioning regarding existing policies associated with mental health issues. Therefore, it behooves for the military to maintain public ignorance about the psychological realities of war to sustain positive civic opinion. The military accomplishes this in a variety of ways, including: (a) enacting PR policies that either completely or partially prohibit verbal or written public disclosures about the extent of its mental health problem (e.g., Menninger, 1966; Russell et al., 2016); (b) restricting tracking and/or disclosure to only a handful of psychiatric diagnoses [e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injury (TBI)] versus the full spectrum of war stress injury (e.g., Russell & Figley, 2015a, b); (c) ensuring there is no single centralized agency responsible for tracking and reporting mental health needs throughout the DoD (e.g., Russell, Butkus, & Figley, 2016a, b); (d) publishing prevalence data that is intentionally vague versus actual numbers (Russell & Figley, 2015a); and (e) avoiding to publish real-time data on mental health casualties, disability pensions, etc.

In regard to the latter point, the DoD publishes real-time casualty statistics via a centralized database maintained by the Defense Casualty Analysis System (DCAS; www.dmdc.osd.mil/dcas/pages/casualties.xhtml) that includes military and DoD-civilian personnel killed and wounded in action, as well as those who died, became ill, or were injured for noncombat reasons (e.g., accidents, illness, self-inflicted). Per DCAS (2017): “Reports are used by DoD organizations, external government agencies, both houses of Congress, the President, the news media, and the general public. The data contained in this site can be used to understand trends in casualties” (retrieved from: www.dmdc.osd.mil/dcas/pages/casualties.xhtml). However, the DCAS does not track or report prevalence of war stress injury despite the trend of psychiatric casualties outnumbering the combined totals of medically wounded and killed in action since WWII (e.g., Russell et al., 2017a).

Publicity Blackout Policies

The military use of PR blackout policies to avoid public disclosure of its mental health problem was evident during the Second World War (WWII). For example, the Director, Bureau of Public Relations, War Department, and other high-ranking officials distributed the following memorandum on 28 April 1944:

Subject: Statistical information by percentages, rates, or numbers of neuropsychiatric casualties in the armed services is classified. The release of statistical information as indicated above constitutes a violation of AR 380-5 and Article 76, Navy Regulations. The following policy will govern all Army and Navy releases for publication of information concerning neuropsychiatric casualties of the Armed Forces. All material on this subject will be checked for accuracy by the Surgeon General’s Office, U.S. Army, before final clearance by the Review Branch, War Department Bureau of Public Relations (Menninger, 1966, p. 141).

Public outrage and protests over the unexpectedly high volume of psychiatrically disabled soldiers returning from the war led to a September 23, 1944, inquiry by the Army Inspector General (IG) “concerning the handling and diagnosis of psychoneurotics within the Army” (Menninger, 1966, p. 148). The IG openly criticized the military’s blackout policy, forcing the Chairman of the Board of Declassification of Medical and Scientific Reports of the Surgeon General’s Office to issue a 1945 memorandum requiring: “Full publicity of the psychiatric problem should be given in a factual manner” (Menninger, 1966, p. 148). Yet, even as WWII ended and the country turned its attention toward helping reintegrate millions of veterans, the military’s publicity blackout was resolute:

On 29 June 1945, Joint Security Control issued a memorandum, again listing “Topics To Be Withheld From Publication.” In this memorandum, there was the specific note under miscellaneous subjects which read as follows: “Statistics (percentages, rates, numbers, names or identifiable photographs) of Neuropsychiatric Casualties” (Menninger, 1966, p. 147).

In response, the Army’s Chief Neuropsychiatry Consultant, Brigadier General Menninger issued the following rebuttal to headquarters:

The public relations and publicity policy with regard to neuropsychiatry involve a problem of great magnitude. It affects the national life. There is an urgent need for frank and extended publication in this field. By a liberal policy of public education, the War Department can give its support and aid to those veterans discharged for neuropsychiatric causes (Menninger, 1966, p. 148).

In summarizing lessons learned from WWII PR, Menninger (1966) candidly concluded:

If we are to learn any lesson, it would certainly be the importance of establishing full-time public relations officer in this field (neuropsychiatry) with the authority of the War Department to release such information as seemed indicated. Only by such methods can impending problems be attacked aggressively and the public educated, thereby avoiding the experience of this war and the common welfare of communities ignored (p. 250).

Contemporary Publicity Blackout in Afghanistan and Iraq Wars

Even in the twenty-first century, the U.S. military’s effort to avoid public disclosure of its mental health crisis is still evident, both from covert circumstantial facts as well as overt written policies. In regard to the former, the fact that the DoD does not have a single agency responsible for maintaining and reporting accurate mental health prevalence data throughout the DoD (e.g., Russell et al., 2016a), by itself, constitutes a publicity blackout. For example, the DoD’s Armed Force Health Surveillance Center and DoD Deployment Health Center (www.pdhealth.mil/clinical/psychological-health-numbers/mental-health-disorder-prevalence-among-active-duty-service) can provide only mental health data gleaned from service members seen by military medicine via its electronic health record, but do not capture workload from a number of other agencies responsible for the provision of mental health services (e.g., base community counseling centers) (Russell et al., 2016a).

The IOM (2014b) has repeatedly called on the DoD to “dedicate funding, staffing, and logistical support for data analysis and evaluation” (p. 84). Yet, comprehensive independent review after review reports, for the federal government, in particular, the DoD and the VA, in many cases, their responses do not match the extent of the problems, and “many readjustment needs are unmet or unknown” (e.g., IOM, 2013, p. 472). Consequently, since the outset of the Afghanistan and Iraq Wars, prevalence estimates for war stress injury are typically limited to a handful of psychiatric diagnoses (PTSD, depression, generalized anxiety, substance abuse, and TBI) as opposed to the full spectrum (Russell & Figley, 2015a). Moreover, the vacuum of centralized reporting in the DoD has been filled by a plethora of research studies within and outside the DoD and VA, resulting in wildly varying prevalence rates of specific post-deployment diagnosis, like PTSD ranging from 2 to 60% (e.g., Russell & Figley, 2015a). In other words, anyone and everyone is free to “cherry pick” statistics to fit their agenda or theory, resulting in chaos and controversy about the true state of mental health affairs, while conveniently providing the DoD plausible deniability. In contrast, on the medical side, there is no controversy or confusion around the number of military personnel with traumatic limb amputation, positive HIV, pregnancy, or other medical conditions, because there is only one single agency that is accountable, with a centralized database responsible for accumulating and taking care of medical needs.

Overt Attempts to Delay Recognition of Mental Health Crisis

Amid concerns over public reaction to a mental health crisis, with recurrent media reports of large numbers of untreated veterans separating from the military, suicide spikes, and other signs of social reintegration difficulty, the military ignored a foundational PR lesson from WWII calling for transparency. On May 23, 2006, the DoD published its PR policy, or Public Affairs Guidance (PAG), with the explicit purpose of “To coordinate accurate talking points and messages about the mental health of Soldiers returning from OIF/OEF for all military and VA spokespersons” (U.S. Army, 2006, p. 1).

Desired Effects

All Army spokespersons whether they are PAOs (public affairs officers), commanders, chaplains, healthcare providers, etc., will speak accurately and with one voice on the issue of mental health and deployed and returning Soldiers.

Buy-in and continuity of message with other organizations including National Guard Bureau (NGB), U.S. Army Reserve (USAR) and Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) are established and maintained.

Establish and demonstrate to the American public that even though combat affects all Soldiers mentally and physically, the majority of Soldiers returning from OIF & OEF are mentally healthy and transition home successfully. For Soldiers who may need temporary or long-term medical assistance for mental health disorders, the Army and VA are prepared to provide them the best health care possible during this time (p. 1).

The U.S. Army (2006) PR policy lists numerous “key talking points,” such as: “Unique to this war, is that military leadership is taking a proactive approach;” “The military is doing a number of things to reduce stigma and improve access to care;” “There are numerous opportunities for reserve and National Guard to receive immediate attention;” and “they (Army leaders) are proactively addressing mental health needs of Soldiers with early intervention and working to build resilience” (pp. 2–3)—all areas reported as chronically and seriously deficient by the DoD TF-MH (2007)—co-chaired by the Army Surgeon General. The military’s pre-2006 PR policy reflects a coordinated partial publicity ban intended to delay full disclosure about the actual size and scope of a mental health crisis that 1 year later is described as:

Against the backdrop of the Global War on Terror, the psychological health needs of America’s military service members, their families, and their survivors pose a daunting and growing challenge to the Department of Defense. The immediacy of these needs imparts a sense of urgency to this report. As such, the Task Force urges the Department of Defense to adopt a similar sense of urgency in rapidly developing and implementing a plan of action (DoD TF-MH, 2007, p. ES-4)

Public Deception and Usage of Propaganda

Military efforts to confuse or deceive government officials and the general public about the presence, severity, and broad scope of mental health crises can be detected by actions such as: (a) calculated decision since the Korean War to avoid collecting and/or publishing actual numbers of psychiatric casualties; (b) individual senior military officials releasing distorted, incomplete, or inaccurate statements to the media, Congress, and military populations designed to deny or minimize the crisis; and (c) issuance of written coordinated PR policies or propaganda that contain known or knowable falsehoods with the intention to deceive.

Calculated Deception in Record Keeping and Statistical Accounting

Citizens interested in the history of military mental healthcare can readily access the U.S. Army’s WWI (e.g., Bailey, 1929; Salmon & Fenton, 1929) and WWII (e.g., Glass, 1966a, b) lessons learned analyses. Each volume provides detailed statistical accounting of the psychiatric realities of war with the explicit purpose that future generations never again forget. For instance, transparent and complete data is available on the total numbers of soldiers diagnosed with specific neuropsychiatric conditions, numbers admitted to neuropsychiatric hospitals, numbers psychiatrically screened and rejected, and numbers receiving psychiatric discharges. Importantly, the same level of transparency is missing for the Navy and Marine Corps during the two world wars (e.g., Russell & Figley, 2015b). Nevertheless, after admitting culpability to a self-inflicted mental health crisis caused largely by ignoring WWI lessons (Glass, 1966a), the U.S. Army painstakingly compiled two massive data-filled volumes of WWII psychiatric lessons learned. In total, 1948 pages detailing every aspect of what is required to meet wartime mental health needs led the U.S. Army Surgeon General Heaton (1966) to sternly warn: “With this information so readily available, there can be little excuse for repetition of error in future wars, should they occur” (p. xiv).

Unfortunately, it appears that those lessons have repeatedly been ignored up to the present day (e.g., Russell & Figley, 2015a, b). It could be argued that the military appears to have made a calculated decision to avoid duplicating the transparency of the WWII cohort, opting instead for little to no recording of its psychiatric lessons and purposeful use of vague incomprehensible statistics. Consequently, individuals seeking similar detailed accounting of the psychological effects of the Korean War, Vietnam War, Persian Gulf War, and the Global War on Terror (GWOT) will be disappointed (e.g., Russell & Figley, 2015b). Statistical data on the prevalence of war stress injury are typically limited to incidence ratios of x per 1000 average troop strength for a specific month, year, or region, thus requiring researchers to locate manpower records of troop strength unique to the formula. For example, the Vietnam War cohort reported its prevalence of psychiatric casualties diagnosed with psychosis increased from 1.6 (1965) to 3.8 (1970) per 1000 average annual troop strength and psychoneurosis from 2.3 (1965) to 3.3 (1970) per 1000, but provided no data on absolute or total numbers (Neel, 1991). Surely, the military’s statistical reporting had to collect absolute numbers in order to accurately derive its ratios, but they ignored reporting this precise information instead of giving both.

Another method employed to deceive the general public and minimize the extent of a mental health crisis is by reporting inaccurate and/or incomplete prevalence data based on faulty diagnostic policies. For instance, frontline psychiatry policies have overtly restricted diagnostic labeling of psychologically injured deployed personnel until their condition deteriorates to imminent danger to self or others (Department of Army, 2009; Russell & Figley, 2017a), or covert diagnostic policies have pressured clinicians to avoid more severe and compensable diagnoses, like PTSD, in favor of minor nonservice-connected or compensable diagnoses, like personality disorder (PD), adjustment disorder, etc. (e.g., de Yoanna & Benjamin, 2009; Wilk, Herrell, Carr, West, Wise, & Hoge, 2016).

Deception by Official Authoritative Statements

Transparent acts of public deception are evident when top leaders in positions of authority provide verbal and/or written testimony on the status of military mental healthcare that are within weeks or months of being shown as inaccurate by the military itself. Military officials (civilian and active-duty) in senior leadership roles have ready access to aggregate data and reports on all aspects of mental healthcare (e.g., staffing levels, staff attrition rates, prevalence rates), and/or can cause such reporting to occur by merely asking. It is expected that senior military officials who make authoritative statements about the status of mental health services would either know or should know if those statements are factually true, beyond rare occasions of human error. For instance, readers are encouraged to review official statements by top military leaders to national news media (e.g., Zoroya, 2007a) and congressional testimony from 2004 to 2007 (e.g., Issa, 2007), and compare the factual bases of those statement with the June 2007 DoD TF-MH findings.

Case in point, at the 24 May 2007 Congressional hearing on: Invisible Casualties: The Incidence and Treatment of Mental Health Problems by the U.S. Military, many DoD officials gave testimony clearly contrary to the 16 June 2007 DoD TF-MH report of catastrophic system-wide failure in every aspect of mental healthcare (e.g., chronic, severe staffing shortages, inadequate access to timely, quality treatment), representing an urgent national public health crisis. Representative Issa’s (2007) very pointed questioning is informative. After hearing public testimony by a Deputy Secretary of Defense who oversees military medicine that: “The military health system is second to none in its ability to deliver timely, quality mental health, and behavioral care. In addition, walk-in appointments are available in virtually all military mental health clinics around the world” (Kilpatrick, 2007, p. 61), the Congressman alluded to reading a preview of the DoD TF-MH (2007) findings and retorted:

You had a lot of superlatives in your presentation, and I was a little surprised that there were quite as many of them as there were, terms like robust and touting surveillance programs, pre-deployment health assessments since 1998, mental health care in theater, the use of multi-faith chaplains, etc. It is in your testimony How do you explain the first panel? General Pollock I think did a very good job of saying, look, we make mistakes, things fall through the cracks. You didn’t do that in your testimony. I was a little surprised that, in light of what we are looking at here and some potential for falling through the cracks, that it was sort of gee, this thing says nothing is broken (p. 114).

In regard to severe staffing shortages, Representative Issa (2007) remarked: “I am going through the math and saying I bet you don’t have 400 psychiatrists and psychologists… why is it you are not asking for those kind of resources?” (p. 114) and added: “Again, I am going to go on to General Pollock, but I would really hope when you testify before Congress you come with the problems, not just the superlatives” (p. 114). However, a review of prior years of congressional testimony by military leaders reveals that the talking points are eerily similar from official to official and consistent with written public affairs narratives disseminated at the headquarters of the U.S. Army (2006) and Navy (2007). Issa’s (2007) factual questioning was made possible by a pre-reading of the DoD TF-MH (2007) report that directly contradicted the bright picture painted. Without factual data to the contrary, the military’s authoritative statements largely go unchallenged. Whether intentional or not, public statements by credible military officials have the propensity to mislead and deceive the public.

Military Propaganda and Public Deception

The Task Force arrived at a single finding underpinning all others: The Military Health System lacks the fiscal resources and the fully-trained personnel to fulfill its mission to support psychological health in PEACTIME or fulfill the enhanced requirements imposed during times of conflict (DoD TF-MH, 16 June 2007, p. ES.2).

After 6 years of public statements and sworn testimony to the contrary, on 16 June 2007, the DoD finally became transparent and reported a major public health crisis, caused principally by chronic neglect and cataclysmic institutional deficiencies (DoD TF-MH, 2007). Invisible to the public is that senior military and congressional leaders were well-informed of the mental health discrepancies and required corrective actions as early as 2004 in order to avoid a crisis that would predictably harm countless veterans and their families (e.g., Russell, 2006b). This forewarning included a widely circulated DoD IG’s grievance against military medicine in January 2006, documenting failure in staffing, training, treatment, monitoring, family support, stigma, and organization (e.g., Russell, 2006a; Zoroya, 2007b). This echoed charges by past mental health officers: “A frequent comment by frustrated and harassed psychiatrists during World War II was that responsible authorities failed to heed the lessons learned by psychiatry in World War I” (Glass, 1966b, p. 735).

However, rather than proactively addressing obvious mental health deficiencies, such as severe staffing shortages, attrition, and inadequate treatment (e.g., Russell, 2006a, b), on 23 January 2007, the U.S. Navy issued a PR policy regarding mental health in the form of written Public Affairs Guidance (PAG) with the stated purpose: “All Navy spokespersons whether they are PAOs (public affairs officers), commanders, chaplains, health care providers, etc., will speak accurately and with one voice on the issue of mental health and deployed and returning Sailors and Marines” (p. 1). Per the U.S. Navy (2007) headquarters, the reason for the PAG was “On September 22 2006, Stars and Stripes (Pacific Edition) published an article titled “Officer Sees ‘Perfect Storm’ Brewing in Military’s Mental Health Care System.” The article quoted CDR Mark Russell, a Navy psychologist stationed at U.S. Naval Hospital (NH) Yokosuka [this paper’s first author]. The USA Today article reiterates CDR Russell’s position that the military does not have enough mental health providers” (p. 1). The U.S. Navy’s (2007) PR policy mirrored the U.S. Army’s (2006) existing PAG listing “Key Messages and Talking Points” including:

Navy Medicine’s goal is to ensure that every returning Sailor and Marine receives any necessary mental health care services as early as possible—providing prevention and treatment services as early as possible is the best way to prevent the long-term effects of war.

Navy and Marine Corps leadership are committed at every level to the issue of mental health. They are proactively addressing mental health needs with early intervention and working to build resilience prior to combat deployments.

Navy Medicine has more mental health resources available at home and in theater than ever before in an attempt to provide Sailors and Marines with information about combat stress and its impact on mental and behavioral health.

Navy Medicine continuously monitors access and utilization of mental health assets and is working to increase the number of providers and portals to care where needed (p. 1).

Five months later, the DoD TF-MH (2007), co-chaired initially by the Army and then the Navy Surgeon General, contradicted the military’s official messaging. Moreover, in regard to the U.S. Navy’s (2007) claim of “working to increase the number of providers,” on 28 February 2007, the Navy headquarters issued a memorandum to eliminate its military social work billets, which was reversed only after the June 2007 DoD TF-MH findings were published:

There is an inadequate number of providers. A thorough review of available staffing data and findings from site visits to 38 military installations around the world clearly established that current mental health staff are unable to provide services to active members and their families in a timely manner; do not have sufficient resources to provide newer evidence-based interventions in the manner prescribed (p. 43)… [and] the military faces significant challenges in recruiting and retaining active duty mental health professionals. The number of active duty mental health professionals is likely to continue to decrease unless incentives change (p. 46).

However, manpower and personnel details, including mental health staffing and attrition rates, are routinely tracked and reported throughout the DoD (e.g., Russell, 2006a). Therefore, not issuing authoritative pronouncements of mental health staffing numbers and treatment access, or remaining silent about a known crisis, represent strategies that allow the military’s narrative to continue, and they possibly constitute a public deception that delays necessary remedies to help soldiers with mental health difficulties.

Silencing of Whistleblowers

Another harmful, less conspicuous component to the military’s delay and deception tactic is the silencing of mental health whistleblowers. Federal laws and government regulations provide legal protection of lawful whistleblowers against reprisal (e.g., DoD, 2007). Yet, cases of whistleblowing about military-related mental health issues have not led to legal protections and appear to be systematically overridden by a desire to punish and/or intimidate future potential whistleblowers to prevent or delay unwanted disclosure. For instance, in 2012, the Army suspended several doctors at Joint Base Lewis-McChord who unethically altered the deployment-related PTSD diagnosis of soldiers to nonservice connected psychiatric conditions, like PD, and adjustment disorder, in order to reduce pension costs (e.g., Bernton, 2012a, b). However, unknown to most, the Army suspended the retired Army psychiatrist who informed Congress and the news media about the Army’s illegal diagnostic practices (Phillips, 2013). Similarly, several Army mental health clinicians claimed they experienced retribution after informing the news media about wrongful misconduct discharge practices of deployed soldiers diagnosed with PTSD and TBI at Fort Carson, Colorado (Phillips, 2013). In addition, allegations of reprisal were made by a senior Navy psychologist after speaking out to prevent the current mental health crisis (Russell, 2007; Zoroya, 2007b), as well as two senior VA psychiatrists who publicly revealed harmful pain prescription policies (e.g., Bahorik, 2013; Gray, 2013).

In each of the above cases, mental health whistleblowers initially raised their concerns internally before going public (e.g., Zoroya, 2007a). Moreover, in each instance, the DoD and VA eventually validated the legitimate concerns of patient safety raised by lawful whistleblowers and were ordered by Congress to fix the problem (e.g., Gray, 2013; Phillips, 2013). Taken together, an alarming trend emerges that has a potential chilling effect on shedding public light on future mental health problems.

Delay Through Appeasement, Half-Measures, and Partial Compliance

When a mental health crisis can no longer be denied, the Congress and President will customarily dictate reforms through legislation (e.g., Wounded Warriors Act, 2009) and/or Executive Order (2012). The military might give the public an appearance of concern, commitment, and compliance while delaying full implementation, by engaging in half-measures or partial compliance. For instance, amid rampant reports of unmet military mental health needs and suicides, in October 2005, the Congress mandated the DoD to establish a mental health task force (Shane, 2006). It took the military until May 2006 (7 months) to establish the task force, and then another 13 months to disclose its findings (DoD TF-MH, 2007). There are other times when urgent need for a different approach or learning from past mistakes is called for, yet with little policy changes. For example, “The time for action is now. The human and financial costs of un-addressed problems will rise dramatically over time. Our nation learned this lesson, at a tragic cost, in the years following the Vietnam War” (DoD TF-MH, 2007, p. 63).

It is commonplace for compliance with externally mandated remedial actions regarding military mental healthcare to take years from time of investigation, perhaps in the hope that interest will wane (e.g., Russell et al., 2016b). For example, the Government Accountability Office (GAO, 2015) has conducted multiple investigations describing the DoD’s incremental and partial compliance with mandatory changes to its PD discharge policy, concluding:

The military services lack separation policies that address all of DOD’s eight requirements for separating service members with non-disability mental conditions; both DOD and the services also lack oversight over such separations. From fiscal years 2008 through 2012, DOD required the services to report on their compliance with DOD requirements for PD separations, one of the non-disability mental conditions. Most of the services reported by fiscal year 2012 that they were not compliant with all eight requirements and many of the 20 reports contained incomplete and inconsistent information (p. 1).

Additionally, the GAO (2010) was tasked to reassess DoD’s compliance with repeated recommendations by six separate independent commissioned studies and the DoD’s TF-MH (2007) to reduce stigma and organizational barriers to care concluding:

DOD has efforts underway to improve perceptions about mental health care for service-members and, to a comparably limited extent, deployed civilians, but has not clarified or updated certain policy provisions that may contribute to mental health care stigma. DOD officials and health care providers said that certain policies are unclear or out-of-date and limit career opportunities for individuals who have sought mental health care. A 2014 RAND Corporation report identified 203 DOD policies that may contribute to stigma. DOD is not well positioned to measure the progress of its mental health care stigma reduction efforts (p. 1).

Likewise, the IOM (2014b) has performed multiple studies on the DoD’s PTSD treatment programs, revealing a similar pattern of gradual, but limited compliance: “PTSD management in DoD appears to be local, ad hoc, incremental, and crisis-driven with little planning devoted to the development of a long range, population-based approach (p. 6).”

Basically, it appears that the purpose of the military’s delay strategies might be to avoid expending resources toward mental health problems. Perhaps the military generally does not feel responsible for these problems, does not want to spend money on them, etc. Moreover, delaying recognition and action allows the military to transfer costs of mental healthcare to the VA and private sector. It would appear that the military mindset about mental health might be that any war will be over before the military is forced by outsiders to fundamentally transform its mental health policies.

Harmful Impact of Delay Strategies

No direct empirical evidence exists to test the assertion that the military’s delaying strategies have harmed war veterans and their families, largely due to the strategies outlined thus far. However, anecdotally, an estimated 237 active-duty service members and 22 veterans a day committed suicide during the nearly 2 years it took the DoD to complete its internal review and finally admit to a national crisis of its own creation (DoD TF-MH, 2007; Ramchand, Acosta, Burns, Jaycox, & Pernin, 2011). Untreated war stress injury, such as PTSD, is a problem-multiplier associated with heightened risk of depression, substance abuse, medically unexplained physical conditions, domestic violence, child abuse, divorce, unemployment, homelessness, and criminal misconduct (e.g., Department of Army, 2006; Department of Navy and U.S. Marine Corps, 2010; DVA/DoD, 2010; Russell & Figley, 2015a, b).

However, there are strong disincentives for the military to collect, yet alone report on the true spectrum of war stress injury (e.g., Russell & Figley, 2015a) or clinical outcomes for service members receiving military mental healthcare, despite repeated recommendations from various commissioned studies (e.g., IOM, 2014a). However, one can simply look to the U.S. military subject matter experts who since WWI have cited the critical need for early identification and treatment of war stress injuries as a critical wartime “lesson learned”:

WWI

First, that it is not only in accordance with the best scientific practice to treat soldiers suffering with war neuroses as early and as effectively as possible but to do so is an important contribution toward the conservation of manpower and military morale (Salmon, 1929a, p. i).

WWII

A most pronounced characteristic of the cases seen early in their illness is the profusion with which new symptoms appear and disappear. As time goes on, without treatment, a more stabilized syndrome crystallizes (Grinker & Spiegel, 1943, pp. 7–8).

GWOT

The policy of tolerating long waits for initial mental health clinic appointments is inconsistent with the frequency and magnitude of mental health problems in the military. The stressors inherent in military life make basic mental health services as critical and time-sensitive as basic medical care. For individuals under stress, psychological health problems may quickly deteriorate. Stigma may cause active duty members to delay seeking help. As such, timely intervention is crucial (DoD TF-MH, 2007, p. 43).

The above statements represent a small sample of evidence that the military is very cognizant of the importance for early identification and treatment of war stress injuries. In fact, the military has adopted public policies mandating as such: “Clinicians should use the 2010 VA/DoD CPG for the Management of Post-Traumatic Stress in the assessment and treatment of patients presenting with symptoms of traumatic stress” (Department of Army, 2012). And yet, peeling away from the rhetoric, independent commissioned studies repeatedly reveal the true extent of the military’s commitment toward complying with its mental health policies:

DoD lacks a mechanism for the systematic collection, analysis, and dissemination of data for assessing the quality of PTSD care. Metrics of program effectiveness, quality of care, program awareness, and availability and acceptance of PTSD services are needed. There are no specific DoD policies or procedures that stipulate the use of measurement-based care for PTSD and no consistent use of standardized outcome measures, before, during, or after treatment (IOM, 2014b, p. 87).

Such contradictions between official policy pronouncements and actual actions on the ground are evidence of inconsistency and half-measures. We found analogous evidence of marginal, partial, and noncompliance with mental health regulations in every aspect of military mental healthcare, including screening, prevention, assessment, treatment, substance abuse rehabilitation, TBI screening, reintegration, family support, staffing, stigma, data management, service delivery, and training, (e.g., Russell et al., 2016b). Therefore, strategies intended to avoid implementing war trauma lessons by delay or deception are invariably harmful to veterans, their families, and society.

Strategy 7: Faulty Diagnosis and “Backdoor” Discharges

Being diagnosed with a mental health condition is the leading reason for military administrative separations (Hoge, Toboni, Messer, Bell, Amoroso, & Orman, 2005), but proper diagnosis is also required for timely access to appropriate high-quality treatment (e.g., DVA/DoD, 2010). Another tactic the military relies upon to prevent psychiatric attrition, treatment, and disability pensions is avoiding accurate psychiatric diagnosis by rendering faulty and highly stigmatizing diagnoses (e.g., PD, lacking moral fiber) and awarding diagnoses that allow for administration separations (ADSEP) that are devoid of service-connection (e.g., adjustment disorder) and eligibility for VA benefits or what is oft called “backdoor” or “bad paper” discharges.

Policies for Avoiding Diagnosing War Stress Injury

Thus, a solution was found for the excessive medical discharge of “psychoneurotic” cases, which consisted of both a change of psychiatric nomenclature and a tightening of the medical discharge process. The benefits of this hard-won lesson learned in World War II were continued during the Korean War and have become a permanent part of the policies and procedures of military psychiatry in the U.S. Armed Forces (Glass, 1966a, p. 757; U.S. Army Office of Surgeon General).

As illustrated above, the military regularly establishes policies that restrict psychiatric diagnosis of war stress injury. While some or many service members may benefit from policies that limit psychiatric diagnosis due to possible stigma, others are harmed by delaying appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Use of punitive and highly stigmatizing labels pertaining to cowardice (e.g., lacking moral fiber), desertion, malingering (e.g., gold-bricker, pension-seeking neuroses), and hysteria [e.g., Not Yet Diagnosed Neurotic (NYDN) in place of shell shock], as well as euphemisms conveying transient stress reactions expected to resolve rapidly with brief respite (e.g., combat fatigue, battle fatigue, combat exhaustion, flier’s fatigue, combat stress reaction, combat and operational stress reactions), all represent military policies for avoiding psychiatric labeling with the explicit purpose of preventing psychiatric attrition, treatment, and pensions (e.g., Russell & Figley, 2017a; Russell et al., 2017b).

Insight into the military’s pejorative view toward psychiatric diagnosis is gleaned from the U.S. Army (1944) Office of the Surgeon General’s Memorandum on Psychoneurosis (Combat Exhaustion). The diagnosis of psychoneurosis was the acceptable medical label at the time and is a precursor to modern-day diagnoses of anxiety disorders, PTSD, and somatoform disorders. However, the U.S. Army (1944) defined psychoneurosis as “a condition, not a disease, which results from an individual surrendering to an adverse situation. It manifests itself in many ways and varying degrees from a mild hypochondria to a severe anxiety neurosis” (p. 1031). In regard to etiology, the Army Surgeon General report stated: “The basic causes of psychoneurosis is insufficient courage” (p. 1031). In response to mass psychiatric attrition and disability discharges for psychoneurosis, the Surgeon General advised: “Psychoneurosis is not a problem in the Russian Army. The Russians punish cowardice with death” (p. 1033). Fortunately, other senior medical leaders pushed back against the antidiagnosis bias.

In March 1943, the U.S. Army abandoned its failed social experiment to purge weakness from its ranks via psychiatric screenings. Rather, it reinstated WWI-era frontline mental health services because “The problem of neuropsychiatric disabilities under modern battle conditions has been a serious one. Approximately 20 percent of all nonfatal casualties are psychiatric in origin” (U.S. Army, 1943, p. 11). In addition, the Army mandated changes in diagnostic classification: “Hence, the only diagnosis permitted was “exhaustion” in line with the policy established by General Bradley’s directive in II Corps on 26 April 1943” (Glass, 1966a, p. 11).

Justification for the military dictating psychiatric diagnostic practices includes concerns about the iatrogenic and stigmatizing effects of psychiatric labels, like psychoneurosis, along with self-fulfilling prophecies of treating war-stressed soldiers as psychiatric patients (e.g., Russell & Figley, 2017a, b). Additionally, reports of successfully returning 60 to 98% of acutely emotionally injured soldiers back to the frontlines after brief respite periods, coupled with anecdotal reports of significantly lower RTD rates when soldiers are medically evacuated and treated for psychiatric diagnosis, provided some face validity to the military’s policy of avoiding psychiatric diagnoses as beneficial to the health and well-being of the troops (e.g., Russell & Figley, 2017b). However, the primary impetus for the military’s change in practice in dictating psychiatric diagnoses is more straightforward: “With the high rates of medical separations threatening to decimate the Army, concern reached the highest military authorities. On 11 November 1943, the War Department reversed the previous liberal discharge policy and established a policy of salvage and maximum utilization of marginal personnel. A prompt effect of this directive was a precipitous decline of the medical discharge rate” (Glass, 1966a, p. 755). Importantly, some senior Army psychiatry leaders disagreed with a headquarter-driven diagnostic doctrine:

It has been suggested that cases of psychoneurosis should be designated by other terms in the hope of escaping the stigma attached to psychoneurosis. This office is strongly opposed to such a policy. There is ample evidence as to the unwisdom of employing euphemisms for well-established medical entities. The difficulty is not with the term, but rather with the attitude toward and understanding of the term (Colonel Menninger, 1944, cited in Menninger, 1966, p. 814).

After World War II, publication of WD Technical Bulletin 203 significantly revised diagnostic nomenclature into two categories: (1) transient personality reactions that were divided into either combat exhaustion or acute situational maladjustments; and (2) immaturity reactions that could be applied to chronic symptoms and lead to administrative separations (e.g., PD, Glass, 1966a)—essentially eliminating psychiatric diagnoses that might result in medical discharge and disability pension. Predictably, the military’s new diagnostic policies had the desired effect:

The new diagnostic categories made unnecessary the widespread usage of the term ‘psychoneurosis’ for situationally induced psychiatric disorders. As a result, the incidence of psychoneurosis, a distant cousin to PTSD, declined sharply and remained at low levels even during the Korean War (Glass, 1966a, p. 756).

Importantly, the military’s diagnostic policies meant that soldiers who were unable to RTD because of more chronic or severe stress reactions would be more susceptible to charges of cowardice, malingering, and/or predisposed weakness (e.g., PD; Lerner, 2003).

Contemporary Diagnostic Policies

Today, the military’s diagnostic policy remains essentially unchanged although the labels have evolved. For example, combat and operational stress control (COSC) personnel are required to defer making psychiatric diagnosis except under specific circumstances to preserve the soldier’s expectations of normalcy and return to duty, as well as avoiding stigma associated with psychiatric labeling in that: “It is both inappropriate and detrimental to treat Soldiers with COSR (combat and operational stress reaction) as if they are a BDP (behavioral disordered patient)” (Department of Army, 2006, p. 11-1). Amidst a plethora of negative publicity and Congressional scrutiny over the military’s use of backdoor discharges to manage its mental health problem, the Department of Army (2012) published its policy on psychological assessment and diagnosis of war stress injury:

Military healthcare providers understand that caution is required in attributing current PTSD-like symptoms to certain diagnoses that can result in harmful clinical, occupational, or administrative consequences for the SM (service member), particularly malingering, PDs, or adjustment disorders. These conditions are often perceived as judgmental or pejorative, can result in administrative separation (or Uniform Code of Military Justice action in the case of malingering), and/or can influence how other medical care providers approach or treat patients when they see one of these diagnoses in the problem list. Patient-centered care within a culture of trust requires that care providers focus on patients’ primary concerns, and these diagnoses, when inappropriately used, can damage therapeutic rapport and interfere with successful care (p. 4).

However, the DoD’s commitment to its diagnostic policy is best determined by the level of compliance and accountability of military personnel choosing to uncharacteristically disobey authority. To that end, the GAO’s (2010) reinvestigation of PD discharges shows:

Most of the services reported by fiscal year 2012 that they were not compliant with all eight requirements and many of the 20 reports contained incomplete and inconsistent information (p. 1).

Moreover, in 2016, the Secretary of Army responded to congressional calls for investigating allegations of noncompliance with its discharge policies by wrongfully awarding 22,194 OEF/OIF soldiers diagnosed with war stress injury (e.g., PTSD, TBI) an other than honorable (OTH) ADSEP for misconduct instead of considering treatment, revealing:

The Army remains confident in the administrative processes that define misconduct separation procedures. Although the Army was not always able to produce evidence that a mental health evaluation was considered by the separation authority, that finding alone does not mean the separation authority did not review it, or that the Army was non-compliant with 10 U.S.C. §1177 (Secretary of Army, 2016; p. 1).

Potential Harm from the Military’s Diagnostic Policies

While deferral of diagnosis may have merit in some or many cases, the military’s diagnostic policies can also cause harm by compounding problems and delaying access to appropriate treatment. According to the U.S. Army, “Once mental disorder symptoms emerge, the most effective strategy for ensuring recovery lies in prompt application of evidence-based treatments” (J-MHAT, 2011, p. 78). In 2004, the DVA and DoD published their joint practice guidelines for managing post-traumatic stress that included expert consensus recommendations for use of the identified evidence-based treatments (DVA/DoD, 2004). The practice guidelines were updated in 2010 and explicitly state the necessity for timely PTSD treatment: “The clinically significant symptoms cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. The symptoms last more than 3 months after exposure to trauma. Chronic PTSD is unlikely to improve without effective treatment” (DVA/DoD, 2010, p. 24). However, the military’s RTD mandate coupled with restricting psychiatric evacuations for treatment outside war zones inevitably results in delays in accessing quality, effective treatment (e.g., Russell & Figley, 2017c). Consequently, returning veterans with unidentified and/or untreated war stress injury are at high risk of a host of post-deployment readjustment problems that could result in legal involvement, family conflict, and suicide (e.g., DVA/DoD, 2010; Russell & Figley, 2017c).

Faulty Diagnosing of War Stress Injury

A major concern for war veterans and their families is whether a potential or actual war stress injury is intentionally not diagnosed, and, instead, the service member is given a label only related to their misconduct or a pre-existing nonservice-connected condition. For instance, drug use is frequently associated with war stress injury like PTSD (e.g., DVA/DoD, 2010) but is also grounds for legal action and OTH ADSEP. Also, war veterans can be given diagnoses such as PD, adjustment disorder, or schizophrenia that are not rated as service-connected, thus subject to potential loss of VA benefits (e.g., DoD, 2017). For instance, during the Vietnam War, relatively low (2 to 5%) rates of classic “combat exhaustion” or “combat fatigue” casualties were heralded by military leaders as a victory over combat stress, attributed to a 12-month rotation and frontline psychiatry policy intended to reduce attrition (Jones, 1995). At the same time, some 300,000 Vietnam veterans were diagnosed and discharged with nonservice-connected disabilities (Ader, Cuthbert, Hoechst, Simon, Strassburger, & Wishnie, 2012) in the context of exceedingly high incidence of “character and behavior disorders,” including diagnoses such as PD, substance abuse, and “indiscipline” (akin to misconduct stress behaviors), as well as dramatic rises in “psychosis” 1.6 (1965) to 3.8 (1970) per 1000 (e.g., Russell & Figley, 2015b).

Contemporary Trends of Faulty Diagnosing

There is no evidence of a broad military conspiracy to wrongfully alter diagnosis to reduce costs of treatment and pensions. However, a string of media stories reveal that such practices do exist. For instance, an Army psychiatrist was audio-recorded disclosing to his Army patient widespread pressure exerted on mental health clinicians to avoid giving PTSD diagnosis to war veterans: “Not only myself, but all the clinicians up here are being pressured to not diagnose PTSD and diagnose Anxiety Disorder Not Otherwise Specified instead” (de Yoanna & Benjamin, 2009). A 2012 news story revealed a widely circulated Army memo from medical leaders at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Tacoma, Washington, advising mental health providers that a PTSD diagnosis costs $1.5 million over a service member’s lifetime and warned doctors to be careful about “rubber-stamping” the diagnosis, in the interest of saving taxpayer dollars (Bernton, 2012a, b). An investigation by the Seattle Times and Washington State Senator Patty Murray revealed unethical conduct by a forensic mental health team changing the post-deployment PTSD diagnoses of 285 soldiers to nonservice-connected psychiatric conditions, like PD and adjustment disorder, leaving them potentially ineligible for medical disability compensation and VA benefits (Bernton, 2012a, c).

Moreover, a recent anonymous survey of 543 Army mental health providers reported clinical data for 399 service member patients, of whom 110 (28%) were reported to be suffering from PTSD (Wilk et al., 2016). However, an audit of the electronic health records revealed that 41% of soldiers reported to have PTSD by their mental health provider were not actually given a PTSD diagnosis (Wilk et al., 2016). Instead, they were diagnosed with administrative situations (e.g., post-deployment related encounter) or lesser psychiatric conditions, like adjustment disorder. The most common reason for not recording PTSD was reducing stigma or protecting the service. However, whatever the rationalization, rendering faulty diagnosis is considered unethical by professional mental health associations (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2002) as well as a violation of the military’s own policies. For example, per Department of Army (2012), “An adjustment disorder diagnosis should not be given if there is evidence that the individual has another specific Axis I disorder that explains the symptoms;” such as PTSD (p. 7). Such misdiagnosing of war stress injury like PTSD is problematic for a host of reasons: (a) prevents military personnel from requesting service-connected disability benefits after they leave the military, (b) can interfere with continuity of care and receiving appropriate PTSD treatment when service members change duty stations every 2–4 years, (c) underestimates mental health demand and needed resources by distorting military prevalence statistics that are based entirely on electronic health record diagnoses, and (d) working around stigma serves only to reinforce stigma in the military.

Backdoor Discharges

Diagnosis, however, was of paramount importance. On the one hand, psychoneurosis was classified as an illness for which an honorable discharge could be readily accomplished under medical auspices. On the other, a diagnosis of an inadequate or other PD which was not considered an illness would result in the return of the patient to duty for possible administrative discharge because of inadaptability or undesirable habits and traits of character. Such “Section Eight” discharges could be white (honorable) or blue (without honor) with the onus of social disapproval as well as the denial of certain veteran’s benefits (Glass, 1966a, p. 732).

One strategy used by the military for service members with war stress injuries is to administratively separate (ADSEP) said veterans, which is also called backdoor discharges (e.g., GAO, 2008). Backdoor discharges can originate through either legal or medical channels. They simultaneously send message to the remaining unit members and serve to reduce costs associated with psychiatric treatment, VA benefits, and disability pensions.

The Legal Backdoor: “Bad Paper” Discharges

Service members convicted by courts-martial or administratively adjudicated for a pattern of misconduct (e.g., repeated minor rule violations) are subject to “bad paper” discharges, including bad conduct or dishonorable discharges, or an OTH ADSEP. This results in forfeiture of military retirement pension, VA disability, and treatment benefits, as well as presenting significant barriers for future employment (see Russell et al., 2017b). Frequent reasons for bad paper discharges are substance abuse (e.g., illicit drug use, wrongful prescription drug use, repeat DUI), interpersonal violence (e.g., sexual assault, domestic violence, child abuse), absence without leave (AWOL, desertion), and patterns of misconduct (e.g., repeatedly being late to work, disrespectful conduct, minor rule violations; Bernton, 2012e; Kors, 2010; Phillips, 2013; Russell et al., 2017b). All are also common sequelae of war/traumatic stress injuries, like PTSD (e.g., DVA/DoD, 2010) and misconduct stress behaviors (e.g., Department of Army, 2006). Consequently, the majority of mentally ill or war stress-injured veterans discharged for misconduct are traditionally barred from receiving psychological health and substance abuse treatment both during and after military service (e.g., GAO, 2017).

Adverse or OTH ADSEP for patterns of misconduct or in lieu of courts-martial is often used by Commanders to expeditiously punish and get rid of problematic personnel, which is deemed necessary to maintain good order and discipline within the military (e.g., GAO, 2017; Kors, 2010; Phillips, 2013). The problem, however, is when military personnel are subject to bad paper discharges during or after deployment(s) and who otherwise have exemplary service records prior to deployment. We are not suggesting that war veterans who commit serious crimes (e.g., murder, rape) should not be held legally accountable for their actions. Most military leaders and legal personnel need to balance the legitimate circumstances of war veterans with the needs of the service and legal justice. However, some leaders may intentionally misuse their power to punish burdensome war veterans, or do so out of benign neglect, therefore, failing to consider mental health interventions prior to legal redress when appropriate (e.g., Phillips, 2013).

Concerns over Backdoor and Bad Paper Discharges

Multiple news media reports paint a tragic portrait of the military’s wrongful use of the legal backdoor to deal with veterans with war stress injury (e.g., Kors, 2010; Phillips, 2013; Murphy, 2011). During WWII, a reported 90,000 military personnel received OTH ADSEP for misconduct (Ginzberg, 1959). The military’s bad paper stratagem for dealing with its mental health dilemma intensified during the Vietnam War. For instance, some 560,000 Vietnam veterans reportedly received discharges under conditions that were less than honorable, with 260,000 of those “bad paper” discharges—either OTH (also sometimes termed undesirable), bad conduct, or dishonorable discharges, raising the specter of backdoor discharges (Izzo, 2014). Per Congressional leaders:

Many bad-paper veterans are among the 250,000 ex-combat soldiers who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder. They have a higher incidence of unemployment, violent behavior, alcohol and drug abuse, family problems and homelessness than other veterans. Yet we won’t give them the treatment that could help them heal. They served their country and deserve treatment for their war wounds, physical and mental (Waters & Shay, 1994, p. 1).

In 2007, a high-ranking Navy doctor was on advisory to colleagues that the military is discharging Marines and Soldiers for misconduct when in fact they are merely displaying symptoms of PTSD (Carpenter, 2010). This was followed by a 2011 Stars and Stripes article describing multiple cases of previously deployed soldiers with prior clean records and diagnosed with war stress injury (e.g., PTSD, TBI, depression, substance abuse) who were reportedly pressured by their commanders to accept OTH ADSEP instead of courts-martials for relatively minor misconduct, including 10 cases of first-time drug use (Murphy, 2011). In June 2014, the Army Surgeon General launched an investigation into frequent complaints about Army mental health clinicians conspiring with Fort Carson commanders to deny PTSD diagnosis of returning war veterans in favor of OTH ADSEP for misconduct (e.g., Phillips, 2013; Secretary of Army, 2016). On 28 October 2015, the Army reportedly gave 22,194 war veterans OTH ADSEP for misconduct instead of treatment for post-deployment diagnosis of PTSD, TBI, or other psychiatric conditions (Zwerdling, 2015). Furthermore, on 4 November 2015, 12 U.S. Senators tasked the Army to investigate complaints of wrongful legal backdoor discharges (Secretary of Army, 2016).

In response, on 16 April 2016, the Secretary of Army reported an internal audit of the 22,194 ADSEPs, revealing that a total of 6364 discharged soldiers were diagnosed with a potential war stress injury, 4837 soldiers with PTSD, and 2624 with TBI (Secretary of Army, 2016). The remaining 15,830 discharged soldiers were excluded from review because of diagnoses other than PTSD/TBI, in contrast to everything known about the spectrum of stress injury (e.g., Department of Navy and U.S. Marine Corps, 2010). Rather than make a good-faith effort to investigate claims of improper backdoor discharges, the Army proceeded to further eliminate cases to be reviewed by utilizing rigid case selection criteria (e.g., only soldiers diagnosed within 2 years of deployment). Consequently, the Army’s internal audit found that “only” 3327 soldiers diagnosed with combat-related PTSD and/or TBI were ADSEP for misconduct, but 2933 of those received “honorable discharges,” with the remaining 324 soldiers receiving OTH (Secretary of Army, 2016). However, upon further scrutiny, the Army reversed itself and said that 96% of 2933 soldiers actually received General, not honorable discharges (Zwerdling, 2016), thus prohibiting certain VA benefits (see Russell et al., 2017b). The Army’s in-depth analysis of the 324 OTH discharges determined the Army complied with its regulations in 64% (293) of the cases (Secretary of Army, 2016). The Army also reported additional audits of alleged wrong doing were conducted and identified another 101 cases warranting further review. In the end, however, the Army Secretary reached the conclusion: “The Army does not routinely separate soldiers for misconduct who have been diagnosed with PTSD or TBI to save time or resources” (Secretary of Army, 2016, p. 1) Table 1.

To our knowledge, this is first time the military has publicly been held accountable to explain its discharge policies of war veterans. While it may be true that the majority of discharges have been fairly adjudicated, the Army’s response raises serious concerns, for example: (a) the lack of independent outside review, (b) selectively reviewing only the 22,128 cases identified in a news story versus a comprehensive fact-finding audit of all discharges, and (c) applying stringent administrative criteria to exclude cases from review. In addition, the policy continues to prohibit war veterans from accessing needed VA mental health treatment (e.g., Ader et al., 2012). Fortunately, under intense congressional scrutiny, the VA will now consider granting treatment access to veterans with bad paper discharges (GAO, 2017). Bad paper discharges are not only an Army problem. For example, Table 1 indicates the steady rise in Air Force misconduct ADSEP, so that is an issue across all service branches (e.g., GAO, 2017).

Recent Findings of Military Compliance with Misconduct Discharges

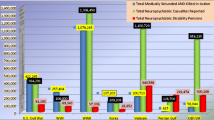

One might assume that, given the level of news media and Congressional scrutiny over its discharge policies, the military might at least temporarily abandon its use of this avoidant strategy. However, in 2017, the GAO released its most recent survey of the DoD’s compliance with legal and policy mandates to eliminate backdoor discharges. The GAO (2017) found that 57,141, or 62%, of the 91,764 service members ADSEP for misconduct from fiscal years 2011 through 2015 had been diagnosed within the 2 years prior to separation with PTSD, TBI, or other psychiatric conditions often associated with misconduct and post-deployment sequelae (e.g., Department of Army, 2009). Of the 57,141 service members, 23%, or 13,283, received an OTH characterization of service (see Fig. 1). Importantly, 6534 previously deployed personnel agreed to accept an OTH ADSEP in lieu or instead of a courts-martial (GAO, 2017). In Dave Phillips’ (2014) Pulitzer Prize series on legal backdoors, several service members featured accused the military of strong arming or threatening them with jail time, bad conduct discharge, and possible felony conviction via courts-martial if they did not or accept a quick, less than honorable exit (ADSEP).

Diagnosis status and characterization of service for service members separated for misconduct from fiscal years 2011 through 2015 (GAO, 2017). Available at https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-260. Notes: The data include data for active-duty officers and enlisted service members who were separated to civilian life. Other separations such as those due to death joining officer commissioning programs or separating to the National Guard or Reserve have been excluded. We defined separations for misconduct as administrative separations for misconduct and administrative separations in lieu of trial by court-martial. We defined diagnoses of PTSD, TBI, or other certain conditions as diagnoses made within 2 years prior to a service member’s separation date. The other conditions included in our study are adjustment disorders, alcohol-related disorders, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorders, depressive disorders, and substance-related disorders. While in this figure we present data on characterization of service for service members diagnosed with PTSD, TBI, or other certain conditions, these proportions largely held true for the smaller population of service members diagnosed with PTSD or TBI. Specifically, 71% of service members diagnosed with PTSD or TBI received “general,” 23% received “other than honorable,” 4% received “honorable,” and 2% received other characterizations of service. aThis category does not include service members who were also diagnosed with PTSD or TBI. For the purpose of our analyses, we included these service members only in the “diagnosed with PTSD or TBI” category. bOther is defined as nonapplicable, uncharacterized, or unknown

Psychiatric Backdoor Discharges

There are two key ways the military can utilize improper or faulty psychiatric diagnosis and ADSEP for problematic personnel with war stress injury, weaponizing stigma, and/or reducing costs associated with psychiatric treatment, VA benefits, and pensions: (1) diagnosis of mental health conditions considered pre-existing and/or nonservice-connected and (2) diagnosis of PD.

Pre-existing Nonservice-Connected Psychiatric Conditions

Whether intentional, or through incompetence, service members with war stress injury can be misdiagnosed and ADSEP with a psychiatric condition the etiological origin of which is not directly connected to military service or being deployed to war zones (e.g., Wilk et al., 2016). During WWII, an Army Brigadier General reported “127,000 men with neuropsychiatric difficulties have been discharged on an administrative basis” (Menninger, 1966, p. 144). Today, such pre-existing or nonservice-connected conditions include, but are not limited to, ADHD, impulse control disorder, sleep-walking, specific learning disorder, adjustment disorder, or other conditions that typically originate in childhood or adolescence or are deemed “unsuitable” for further military service (DoD, 2017). Once diagnosed, service members can be ADSEP under the category of “Convenience to the Government” (DoD, 2017), typically with characterization of discharge as General under honorable, which is less than honorable (DoD, 2017). Essentially, those service members, regardless of time in service and deployment history who are given a General discharge, are typically ineligible for any VA benefits or military retirement pensions unless they are also diagnosed with a service-connected disability. They often experience difficulty obtaining certain civilian employment requiring an honorable discharge (e.g., GAO, 2011).

Military Trends

Note that psychiatric backdoor discharges are not new to the twenty-first century. For example, during WWI, a total of 6196 Army personnel was ADSEP for “character and behavior disorders, including 3,709 diagnosed as ‘constitutional psychopathic states’ (akin to PD), 455 for ‘alcoholism,’ 734 ‘bedwetting,’ 1190 for ‘drug addiction,’ and two for ‘malingering’” (Salmon & Fenton, 1929). In WWII, a total of 163,119 soldiers were ADSEP for unsuitability due to neuropsychiatric reasons, among whom were 2930 for “character and behavior disorders, which includes chronic alcoholism and drug dependence” (Glass & Bernucci, 1966). Service members ADSEP for “psychopathic personality, chronic alcoholism, or sexual perversion including homosexuality, were discharged without honor.” (Bernucci, 1966, p. 484). Prior to 1982, Vietnam War veterans diagnosed with a “pre-existing” mental health condition, such as schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, whether accurate or not, were often medically discharged or ADSEP without VA treatment benefits. This trend of backdoor discharges was reported to have notably increased during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, but absolute numbers are not reported and thus unavailable (Glass & Jones, 2005).

PD

Although the military’s classification of PD has evolved over time, being called constitutional psychopathy (WWI, WWII), then asocial/psychopathic personalities (WWII), and then PDPD (Korean War to present day), the general policies have not. Today, a PD is defined as:

An enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is stable over time, leads to clinically significant distress or impairment in social or occupational functioning and is not better explained as a manifestation or consequence of another mental disorder, or the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., drug of abuse) or another medical condition [e.g., head trauma; American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 645].

Given its developmental nature, a PD is considered a pre-existing (pre-military) and therefore nonservice-connected condition. From the military’s perspective, a PD diagnosis communicates an inherent difficulty adapting to social and occupational demands in adverse environments, with the potential to become a substantial burden on the command and/or a safety risk to self or others. In other words, in PD, predisposed weakness, not exposure to war stress, is the underlying cause of one’s post-deployment troubles. Therefore, service members with a PD diagnosis are routinely ADSEP for having a pre-existing condition that is incompatible and unsuitable for military service. However, by definition, a PD is not diagnosed in adulthood without substantial evidence of earlier maladjustment and only after excluding other psychiatric or physiological conditions (APA, 2013). A history of psychiatric hospitalization and legal conviction typically renders an individual as ineligible to join the military (e.g., GAO, 1998). Since WWI, the military has psychiatrically screened and rejected volunteers and draftees due to possible PD or other psychiatric risk factors as reflected in Table 2.

Once diagnosed, service members may be given an opportunity to remediate via counseling, with a formal written warning that further performance problems will result in ADSEP (DoD, 2017). However, the vast majority of personnel diagnosed with PD are recommended for ADSEP and those with a history of suicidal ideation or attempts are often subject to “expeditious” ADSEP (DoD, 2017). The senior author (mcr) has observed expeditious ADSEP occurring within a week. Individuals are ADSEP for PD under the category of Convenience to the Government (DoD, 2017), typically with characterization of discharge as General under honorable, which is less than honorable (DoD, 2017).

Military’s Wrongful Use of PD Diagnosis and Backdoor Discharge

Anyway, given the fact that both the military and the VA heard this testimony, which is very, very shocking, that there is a systematic and a policy-driven misdiagnosis of PTSD as PD to get rid of the soldier early, to prevent any expenditures in the future which are calculated in the billions of dollars, I would take that pretty seriously if I were you guys and say something about that (Hon. Bob Filner (2007), Chairman, Committee of Veterans’ Affairs; U.S. House of Representatives).

U.S. Army researchers surveyed psychiatrists deployed to Vietnam who reported that, of all possible mental health diagnoses, PD was the most frequent (27%), followed by drug dependence syndrome (15%), which is another ADSEP-qualifying condition (Camp & Carney, 1987). An estimated 300,000 Vietnam veterans received General ADSEP’s with an unknown, but large number of those subject to diagnostic abuses (e.g., Izzo, 2014), carrying stigma and adverse effects on employment.

Contemporary Trend of PD Discharges

From 2000 through 2015, a total of 99,223 active-duty service members were diagnosed with PD by military healthcare (Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center, 2016). It is unknown how many of the 81,223 service members were war veterans. In 2007, media reports surfaced alleging the Army involuntarily ADSEP over 40%, or 28,000 soldiers, for PD due to post-deployment adjustment problems (Kors, 2007; Zwerdling, 2007). On 25 July 2007, the U.S. House conducted hearings on PD backdoor discharges, prompting the committee Chairman Filner to observe:

My concern is that this country is regressing and again ignoring legitimate claims of PTSD in favor of the time and money saving diagnosis of PD. Providing veterans with the correct medical diagnosis is key for a variety of reasons ranging from receiving proper treatment to eligibility for military and veterans’ benefits. Once a service member is diagnosed with a PD, he or she has a much more difficult time receiving benefits and treatment at the VA (p. 1).

In 2008, the GAO was charged by Congress to review the DoD’s PD discharges amid widespread reports of wrongful backdoor discharges of war veterans. The GAO (2008) reported that out of a sample of 31,000 personnel ADSEP for PD, it found 2900 service members had deployed to OEF/OIF war zones. Subsequently, the Congress has enacted several laws (e.g., National Defense Authorization Act, 2010) and the DOD (2010) has modified its ADSEP policies governing the military services’ handling of PD and misconduct separations in cases involving PTSD and TBI (e.g., GAO, 2010). Consequently, Figs. 2 and 3 reveal a dramatic reduction in military PD discharges since 2007 due to external pressure. However, in 2010, the GAO found the Army, Marine Corps, and Navy remained noncompliant with the DoD’s revised PD discharge regulations, leaving open the possibility for backdoor discharges. In fact, even as recent as 2015, the GAO cited problematic PD and other nonservice-connected psychiatric discharges:

DOD and three of the four military services—Army, Navy, and Marine Corps—cannot identify the number of enlisted service-members separated for non-disability mental conditions because, for most separations, they do not use available codes to specifically designate the reason why service-members were separated.

Because the three military services are using the broad separation code “condition, not a disability” for most separations, the resulting data cannot be used to identify the number of service members separated for non-disability mental conditions. There is no other systematic way to track these separations (GAO, 2010, pp. 9–10).

Number of military personality disorder administrative separations. Note: Data from U.S. Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, Navy, National Guard, and Coast Guard (see Sidibe & Unger, 2016)

Nondisability personality and adjustment disorder separations: U.S. Air Force Only. Source: http://nlgmltf.org/military-law-library/publications/adjustment-disorder-discharge/