Abstract

Purpose of Review

The most common and biomechanically influential pathoanatomic risk factor for recurrent patellofemoral instability is trochlear dysplasia. Sulcus-deepening trochleoplasty is a procedure developed to address high-grade trochlear dysplasia in the setting of patellofemoral instability. The purpose of this paper is to outline the current classification and surgical management of trochlear dysplasia as well as to review the current literature on the clinical outcomes and complications of sulcus-deepening trochleoplasty.

Recent Findings

This review outlines the most recent literature reporting evidence behind the decision-making to perform a trochleoplasty in the setting of patellofemoral instability and high-grade trochlear dysplasia. Critical parameters include grade of trochlear dysplasia, severity of symptoms, pertinent physical examination findings, surgical techniques, modifications for skeletally immature patients, and considerations for the revision setting. Historic studies have elicited concerns regarding high reported complication rates for trochleoplasty; however, recent studies consistently report good clinical outcomes and acceptable complication rates, similar to those of other patellar stabilizing procedures. The addition of a trochleoplasty in patients with high-grade dysplasia results in a lower re-dislocation rate, significant improvements in patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) as well as high levels of patient satisfaction and return to sport.

Summary

The use of sulcus-deepening trochleoplasty for the treatment of high-grade dysplasia and recurrent patellofemoral instability is a well-established technique with good outcomes and an acceptable complication profile. In patients with high-grade dysplasia, trochleoplasty results in lower re-dislocation rates, high patient satisfaction scores, and good clinical and functional outcomes. An understanding of trochleoplasty and its indications should be in the armamentarium of surgeons treating patellofemoral instability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recurrent instability of the patellofemoral joint is a relatively common condition that can result in debilitating pain, loss of function, and reduced quality of life [1••]. The incidence of patellar instability in the general population is 6 per 100,000, and in the adolescent age group it is known to be 7-times higher affecting 30 out of 100,000 patients [2]. Approximately 75% of patients presenting with patellofemoral instability are female [3, 4]. Multiple demographic and pathoanatomic risk factors contribute to patellofemoral instability. Patients present with a varied combination of these risk factors, creating significant challenges for clinicians treating this patient population.

Pathoanatomic risk factors including trochlear dysplasia, patella alta, torsional malalignment of the femur and tibia, a lateralized tibial tubercle, and genu valgum can all contribute to the risk of lateral patellofemoral instability. Of these, trochlear dysplasia has been identified as the pathoanatomic risk factor with the greatest biomechanical contribution to patellofemoral instability [5]. Trochlear dysplasia is a pathoanatomic variant where the femoral trochlea develops abnormally, resulting in a shallow or convex groove. Studies have shown that the morphology of the distal femur is determined early in utero [6]. A genetic cause for trochlear dysplasia has also been investigated [7], and may have a familial association such as that reported in countries such as France [8]. Trochlear dysplasia has been shown to cause increased patellofemoral pressures, decreased patellofemoral contact area, and significantly reduces the force required to dislocate the patella in the first 45° of flexion [9, 10••]. Up to 96% of patients that present with patellofemoral instability demonstrate some degree of trochlear dysplasia [8].

Classification of Trochlear Dysplasia

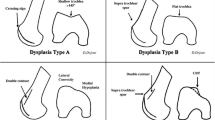

Considering the complex and variable nature of trochlear dysplasia, it is not surprising that a valid and reproducible classification system has been difficult to establish. Dejour’s classification of trochlear dysplasia relies on lateral radiographs in combination with axial imaging and is the most commonly used [11]. The four subtypes of trochlear dysplasia are defined as: Type A—shallow trochlea and crossing sign; Type B—a flat trochlea and a supratrochlear spur; Type C—a double contour secondary to a hypoplastic medial condyle with a convex trochlea; and Type D—the most severe with a combination of all features (Fig. 1).

The Dejour classification of trochlear dysplasia (from Carstensen 2017) [12]

The Dejour classification has been widely adopted however poor interobserver reliability has been demonstrated for its subtypes [13, 14]. Dichotomous classification of high- and low-grade dysplasia has demonstrated greater reliability and has been adopted in some recent studies for this reason [1••, 13, 15]. On a practical level that may aid understanding and guide surgical management, the lack of a lateral buttress can be caused either by an elevation of the floor of the trochlear groove or a deficient lateral condyle. With mild elevation of the trochlear floor, the groove is shallow (Type A/low-grade dysplasia). Further elevation or projection of the base of the groove or sulcus anterior to the anterior femoral line creates the trochlear bump or supratrochlear spur (Type B/D or high-grade dysplasia). In these instances, because the base of the groove is abnormal, a sulcus deepening trochleoplasty is indicated. In other cases, the floor of the groove is at relatively normal height, there is no trochlear bump, but the lateral and/or medial condyle are dysplastic or lower than normal (Type C, high-grade dysplasia). In these instances, elevation of the lateral condyle may be indicated. Although helpful, this explanation is also a simplification of the complex nature of trochlear dysplasia. Development and validation of a comprehensive classification system for trochlear dysplasia must take into consideration many aspects that are not covered by current classification systems. These include variables that delineate the 3-dimensional position, length, and depth of the dysplastic trochlear groove. The following are parameters for future consideration: whether or not, and by how much, the existing groove is medialized by the trochlear bump, the length of the cartilaginous trochlea, the length and location of the dysplastic section of the trochlea, and the relative heights of the femoral condyles [16, 17•]. Further to this, quantifying each of these parameters and their role in patellofemoral instability is critical to help guide future management and appropriately indicate patients for operative intervention. Further studies are required to accurately qualify and quantify these features to better understand the pathology of the dysplastic trochlea.

Surgical Management of Trochlear Dysplasia—Trochleoplasty

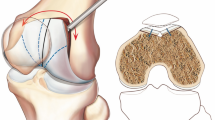

Various surgical techniques have been developed over time to address trochlear dysplasia. The lateral facet elevation, first described by Albee, is an elevating osteotomy of the lateral condyle accomplished by the interposition of bone graft under the lateral edge [18]. First described by Masse in 1978 [19] and then modified by Henri Dejour in 1987, the sulcus deepening trochleoplasty is performed by removal of subchondral bone allowing for reshaping of the trochlea into a deeper groove [11]. In the trochleoplasty popularized by Dejour, the cartilage is elevated as a thick osteochondral shell, with at least 5 mm of subchondral bone. This thick-flap technique requires the articular cartilage to be osteotomized to fit the newly shaped sulcus. Fixation of the flap is achieved with hardware, either staples or screws. Bereiter and Gautier further modified the Dejour technique of deepening the sulcus by using a lateral parapatellar approach to elevate a thin (2–3 mm) osteochondral flap. This thin-flap approach does not require an osteotomy of the articular surface as it is more malleable allowing for greater plastic deformation to shape it into the newly formed groove [20]. The flap is secured with a combination of vicryl tapes and suture anchors or compression tacks. Blond and Schottle further modified the thin-flap technique to be performed arthroscopically via suprapatellar portals, with elevation of the cartilage flake, reshaping of bone, and reattachment of the cartilage flake [21]. Other modifications have included a technique to lengthen the lateral condyle proximally using a bone block to provide static tracking support to the patella during early flexion [22].

Senior Author’s Recommendations

The author’s preferred method for performing a trochleoplasty is a thin-flap technique through an anterolateral approach (Fig. 2). This is especially useful in young patients with good quality cartilage and subchondral bone as it allows for a malleable flap. The cartilage is not breached, minimizing trauma to the joint surface. The thin-flap technique allows for easy titration of the depth and length of the trochleoplasty according to the extent of the trochlear bump. In older patients and those with cartilage degeneration in the patellofemoral joint, the thick-flap trochleoplasty allows for the formation of a groove in the presence of stiffer subchondral bone and arthritic changes. In both techniques, a lateral retinacular lengthening is usually necessary because in the setting of high-grade dysplasia the patella usually has significant lateral tilt secondary to the patella riding on the lateral aspect of the trochlear bump.

Clinical and Patient-Reported Outcomes Following Trochleoplasty

Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have analyzed clinical outcomes after trochleoplasty [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30, 31•, 32]. Overall, these studies report good outcomes as well as an acceptable complication rate for patients undergoing a trochleoplasty for recurrent lateral patellofemoral instability and high-grade dysplasia. These studies consistently report a lower re-dislocation rate in patients with high-grade dysplasia when a trochleoplasty is performed concurrent with a medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) reconstruction compared to an MPFL reconstruction in isolation. As with most systematic reviews and meta-analyses, the included studies suffer from inconsistent surgical techniques, diverse patient profiles, a mix of primary and revision procedures, varied application of concomitant procedures, and inconsistency on whether or not an MPFL reconstruction was included.

Reports of high complication and re-operation rates following trochleoplasty have made many, especially in more litigious regions, leery of adopting the trochleoplasty into their armamentarium of treatment options for patellofemoral instability in the setting of trochlear dysplasia. However, there are difficulties in using the available complications and adverse outcomes data on face value due in large part to the heterogeneity of the studies and by the broad and undefined classification of an adverse outcome [33]. The source research papers for reports of these adverse outcomes include a minimum of four different types of trochleoplasty over an almost 50-year period. There has been a significant improvement in surgical technique during that time period which minimizes the potential risk to the chondral cartilage. Also, with the increased utilization of trochleoplasty, there is a learning curve associated with the procedure that should be accounted for in the analyses. In addition, the thresholds that are used to add concomitant procedures are unclear but evolving, which makes comparisons between patient cohorts challenging. For this reason, substantial caution should be applied when considering results based on surgical techniques no longer in use, as well as those studies with small numbers of patients that do not discuss or account for the surgical learning curve.

For this manuscript, only case-series published in the last 10 years using modern trochleoplasty techniques that reported on a minimum of 25 patients were analyzed. This decision was taken to minimize the inclusion of historic surgical indications and techniques. The minimum sample size was based on the threshold most commonly used to describe the learning curve of a surgical technique [34]. Using these criteria, there were outcomes available on 648 patients who had undergone a trochleoplasty as part of their treatment of recurrent lateral patellofemoral instability (Table 1). These outcomes demonstrated that trochleoplasty provides statistically significant improvements in patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) most commonly reported as the Kujala score and the International Knee Documentation Committee Score. The majority of these patients were able to return to their sporting activities (40–92%) and they reported high levels of patient satisfaction (over 88%).

This cumulative research establishes a respectable track-record of improved clinical outcomes following trochleoplasty. Concerns over the potential risks of the procedure can also be assessed using the available literature. Using the same inclusion criteria of studies performed in the last 10 years, with modern surgical techniques and a greater than 25 patient sample size, the complications of trochleoplasty are reported in Table 2. These results indicate that complications after sulcus deepening trochleoplasty are similar to other patellar stabilizing procedures. There was one report of a traumatic detachment of the osteochondral flap and no other severe complications. There are no reports of chondrolysis or rapidly advancing osteoarthritis post trochleoplasty. The majority of the reported complications appear to stem from unaddressed risky pathoanatomy, many are typical complications for a knee ligament reconstruction procedure, and others form part of the natural history of patellofemoral instability. Based on this review of the current literature, reports of significantly higher complication rates and other dangers of trochleoplasty appear to have been overstated.

Layered onto the heterogeneous reporting in most systematic reviews, the historically available patient-reported outcome measures have not been validated specifically in pre- and post-operative patients with patellofemoral instability. Although the common use of these outcome measures in these studies does lend some validity, reliability, and responsiveness data to support their use, further assessment of internal consistency, test–retest reliability, floor and ceiling effects, and reliability are required to ensure the PROMs are measuring what is intended [35•]. Newer disease-specific PROMs such as the Banff Patellofemoral Instability Instrument [36••] and the Norwich Patellar Instability Instrument [37•] have demonstrated validity and reliability, and are promising to evaluate outcomes in the patellofemoral instability patient population. Further study of these PROMs in keeping with the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) taxonomy [38, 39] will be required to investigate reliability, validity, and responsiveness for trochleoplasty.

Surgical Decision-Making in Trochlear Dysplasia—When Should You Add a Trochleoplasty?

For the currently identified pathoanatomic risk factors for lateral patellofemoral instability, the thresholds to determine whether or not to add a concomitant procedure to an MPFL reconstruction are not clear. Trochlear dysplasia suffers from the same lack of surety. Lui et al. demonstrated in a case series of 121 subjects that most patients with high-grade trochlear dysplasia have good outcomes following an isolated MPFL reconstruction [4]. Multiple other studies, however, have correlated high-grade trochlear dysplasia with poorer outcomes after patellofemoral stabilization [1••, 40,41,42,43,44,45].

Does the current literature help with decision-making about when to add a trochleoplasty in a patient who presents with trochlear dysplasia and recurrent patellofemoral instability?

-

1.

Grade of dysplasia: The evidence indicates that only high-grade dysplasia will benefit from a trochleoplasty [46••]. A trochlear bump greater than 5 mm has also been correlated to poorer quality of life scores following patellofemoral stabilization surgery without trochleoplasty [47]. A shallow groove, consistent with low-grade, or Dejour Type A dysplasia will not benefit from the added procedure [48]. If the patient has high-grade dysplasia (Dejour Type B, C, D), the type of dysplasia should dictate which procedure is the most appropriate. When the base of the trochlear groove is elevated significantly, such as in Dejour Type B and D dysplasia, then the patient may benefit from a sulcus-deepening trochleoplasty [46••]. If the condyle is deficient but the groove is at an appropriate position, then an Albee trochleoplasty that elevates the lateral condyle may be of benefit [18].

-

2.

Severity of symptoms: In patients with mild symptoms of instability, the role of concomitant procedures should be considered carefully. In low-demand patients who complain of mild instability, a less invasive procedure, such as an isolated MPFL reconstruction could be considered. In patients with severe symptoms and radiologic evidence of high-grade trochlear dysplasia, a more substantial procedure should be considered. Likewise, in a patient who is functioning well, playing high-level sport with mild to moderate symptoms, the risk–benefit ratio of all ancillary procedures should be taken into consideration when discussing stabilization. In addition, the assessment of the number and severity of pathoanatomic risk factors present in each patient in addition to trochlear dysplasia is essential in the decision-making process. Studies on the risk factors associated with recurrence after a first-time dislocation may provide insight into the clinical and biomechanical consequences of layering of risk factors in patients undergoing a stabilization procedure [49, 50]. An increased TT-TG distance, patellar alta, and femoral anteversion all increase the amount of laterally-directed force that a graft needs to resist in addition to the increased forces dictated by the trochlear dysplasia. Tissue quality demonstrated via generalized joint hypermobility and measured by the Beighton score may lower the threshold at which a redislocation may occur. In the presence of multiple risk factors, the thresholds at which some or all of these are addressed may be lowered [51].

-

3.

Physical examination: A prominent or “jumping” J-sign in the presence of high-grade dysplasia indicates that there is a significant patellar tracking issue. The patella is forced laterally during the initial degrees of flexion as it encounters the trochlear bump and then “jumps” back into the groove in deeper flexion. These motions result in significant lateral forces and a soft tissue reconstruction is unlikely to be successful. This patient presentation should be an indication for considering trochleoplasty [48, 52, 53••].

-

4.

Considerations in the skeletally immature: Skeletal immaturity has historically been a contraindication for trochleoplasty due to the risk of physeal injury and partial growth arrest. More recently, successful outcomes of trochleoplasty performed in patients with open physes have been reported [54•]. Nelitz published a case series of 18 adolescents with high-grade trochlear dysplasia, open distal femur growth plates, and < 2 years of growth remaining. At an average 2.3 years after thin-flap trochleoplasty, good outcomes were reported with no growth arrest or angular deformity evident. The authors recommend the thin-flap trochleoplasty in this age group to minimize the violation of the anterior growth plate [54•]. The best approach for patients with more than 2 years of remaining growth has yet to be established and remains a contraindication for trochleoplasty given the risk of physeal injury.

-

5.

Considerations in the revision setting: Despite good outcomes and an acceptable complication profile, the use of trochleoplasty in the revision setting is more widely accepted than in the primary setting. As with other ligament reconstructions such as anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, the addition of procedures to improve the anatomy, and/or biomechanics of the joint to reduce the force on the soft tissue graft in the revision setting is standard [55]. Many of the studies describing outcomes after trochleoplasty include revision procedures in their numbers, contributing to the heterogeneity of the results and the difficulty in drawing conclusions [56••, 57]. In studies describing failure of isolated MPFL reconstruction, neglecting to address bony risk factors is stated as a significant cause of failure [58,59,60,61]. Revision MPFL reconstruction including addressing any significant risk factors leads to improved patient outcomes although not quite as successful as for primary procedures [60, 61]. In the context of a failed soft tissue stabilization procedure, addressing high-grade trochlear dysplasia by adding a trochleoplasty to the revision MPFL procedure should be contemplated.

Senior Author’s Recommendations

Trochleoplasty should be considered for patients with significantly symptomatic recurrent instability in the setting of high-grade trochlear dysplasia (Dejour B/D) and a trochlear bump greater than 5 mm [1••]. A significant or “jumping” J-sign in the setting of a large trochlear bump suggests that an isolated soft tissue procedure may not be sufficient to counteract the lateral forces, and a bony procedure should be included. Understanding that the thresholds to add a trochleoplasty are not entirely defined, a primary trochleoplasty concomitant with an MPFL reconstruction is preferable in a high-risk patient as opposed to reserving the procedure to a revision setting where patient outcomes are less optimal. This is especially true in the young patient in whom the osteochondral flap is malleable, the healing potential is optimized and there is potential to interrupt the natural history of high-grade dysplasia and patellofemoral instability. In addition, the author supports the orthopaedic principle of fixing at the site of deformity [62]. If the major deformity is at the trochlear, the bony re-alignment should be performed at the trochlea. A lower threshold for undertaking a trochleoplasty should be considered when a patient demonstrates risk factors that are unalterable such as generalized ligamentous laxity or multiple risk factors in combination.

Is an MPFL Reconstruction Necessary in Combination with Trochleoplasty?

There are conflicting opinions regarding the necessity to reconstruct the MPFL in the setting of trochleoplasty [23, 24]. In principle if the MPFL complex is the restraint to lateral translation of the patella, logic dictates that reconstruction of this structure be part of the treatment for patellofemoral instability. Procedures such as trochleoplasty and TTO serve to improve the anatomy and biomechanics of the patellofemoral joint. These bony procedures provide improved patellar tracking and redistribute the forces acting on the joint, but they do not provide stability to the patella. Although in keeping with surgical principles, this concept has not been studied in a methodical manner. One systematic review has compared combined trochleoplasty and MPFL-R to trochleoplasty alone in patients with trochlear dysplasia, and found lower outcome scores and higher rates of residual instability in the isolated trochleoplasty group [24]. In contrast, a more recent systematic review determined there were no differences in outcomes or surgical failure between isolated trochleoplasty versus trochleoplasty in combination with other stabilizing procedures [23]. There is significant heterogeneity in the studies reported in these systematic reviews making any conclusions difficult to draw. Answering these questions will require high-quality prospective data from studies with robust inclusion criteria and valid outcome measures. Until then, adding an MPFL reconstruction or other medial soft tissue stabilizing procedure is consistent with “restoring damaged anatomic structures,” a practice highly recommended by Dejour [52].

Senior Author’s Recommendations

Patients presenting with recurrent lateral patellofemoral instability lack a soft tissue restraint to lateral translation. The primary restraint to lateral translation is the MPFL complex. Any stabilization procedure then must address the primary lesion and provide a checkrein to the patella. The most common procedure to achieve this is an MPFL reconstruction but the soft tissue restraint can also take the form of an MPFL imbrication, an MQTFL reconstruction, an MPTL reconstruction, or a combination thereof. Bony procedures such as trochleoplasty serve to improve the anatomy and biomechanics of the patellofemoral joint but will not provide restraint to lateral translation of the patella. For these reasons, if a trochleoplasty is performed for the correction of patellofemoral instability, it should be accompanied by a medial soft-tissue stabilization procedure, most commonly an MPFL reconstruction.

Concomitant Procedures in the Setting of Trochleoplasty?

Patients with patellofemoral instability present with a variety of demographic and pathoanatomic risk factors necessitating thorough assessment and an à la carte approach to treatment. It is critical for the treating surgeon to understand and identify the risky pathoanatomic and demographic features that are present in each patient and then plan how best to address them. Using the current reference thresholds for each pathoanatomic risk factor, patella alta can be addressed with a distalizing tibial tubercle osteotomy; rotational abnormalities of the femur and tibia can be addressed with de-rotational osteotomies [63•, 64] and lateral tilt can be addressed by a lateral retinacular lengthening or release. Lateralization of the tibial tubercle can be improved with a medializing tibial tubercle osteotomy. It must be kept in mind, however, that the TT-TG distance is a measurement that includes the position of the trochlear groove which is usually medialized in high-grade dysplasia, thereby elevating the TT-TG. A medializing tibial tubercle osteotomy should only be added if there is true lateralization of the tubercle as determined by an increase in the TT-PCL distance [65]. Trochleoplasty will lateralize the trochlear groove improving the TT-TG measurement by up to 10 mm [48, 66, 67]. Performing a tibial tubercle osteotomy to correct the mal-tracking associated with high-grade dysplasia has been recommended as a safer approach to improve tracking than performing a trochleoplasty [68]. While further research is essential, this approach violates the surgical principle of fixing at the site of the deformity to avoid creating secondary deformities [62].

Senior Author’s Recommendations

Each patient presenting with recurrent patellofemoral instability must be thoroughly assessed via history, physical examination, and imaging. History provides demographic risk factors and severity of symptoms. The physical examination will identify many of the pathoanatomic risk factors as well as signs such as apprehension and J-sign unique to each patient. Minimum imaging includes plain radiographs with anterior–posterior, true lateral, and skyline views. Axial imaging in the form of a CT scan or MRI scan is necessary to determine the measurements of trochlear dysplasia, TT-TG, and TT-PCL. A rotation profile using an MRI or CT scan will allow for the calculation of femoral and tibial rotational abnormalities. If needed, sagittal MRI will aid in determining the effect of any increase in patellar height by allowing the measurement of the patellar-trochlear index [69]. Once all demographic and pathoanatomic risk factors are catalogued, a decision can be made regarding the addition of concomitant procedures. Assessment of the patient’s physical demands and psychological readiness for surgery will also play into the final decision. Keeping in mind that a trochleoplasty and MPFL reconstruction is already a large procedure, careful consideration of the necessity of any additional procedures should be taken. Of note, a TTO is not recommended based solely on the TT-TG distance, given that a trochleoplasty will improve the TT-TG by up to 10 mm. An increase in TT-PCL or significant patella alta should be present in order to consider the addition of a TTO.

What is the Risk–Benefit Equation for Trochleoplasty?

This review has established that trochleoplasty for the appropriate indication and performed using modern surgical technique has good outcomes with a low complication profile. Why then, the hesitance to incorporate trochleoplasty into clinical practice? The largest deterrent for surgeons appears to be concern about the risk of progression of patellofemoral osteoarthritis. Rouanet et al. published a 97% incidence of PF OA for a patient cohort 15-year post sulcus deepening trochleoplasty [70]. Although this study is often cited by surgeons concerned about trochleoplasty outcomes, it is important to note that 30% of the cohort had patellofemoral osteoarthritis pre-operatively, and to form the new groove a mallet was used to hammer the cartilage flap into a concave surface. Current research indicates that using more appropriate patient selection and modern surgical techniques, the progression of OA is no higher than those for MPFL reconstruction in isolation [56••, 71, 72]. Taking into account that a patient with high-grade trochlear dysplasia is more likely to develop patellofemoral arthritis [73, 74], an offloading trochleoplasty may alter the natural history of patellofemoral degeneration. This concept is supported by Falkowski et al. who reviewed pre and post-operative MRIs of patients that underwent trochleoplasty and identified a reduction in signal intensity of the lateral patellar facet as a marker of corrected PF articulation [75]. Further studies will be essential to determine how trochleoplasty influences the natural history of patellofemoral instability in the setting of high-grade trochlear dysplasia.

The creation of patellar-trochlear mismatch is another concern raised about trochleoplasty. Recent evidence suggests that the trochlea is the most affected side of the joint in this condition. Balcarek et al. reviewed pre- and post-operative MRIs of 20 patients with high-grade trochlear dysplasia who underwent a trochleoplasty with MPFL reconstruction and compared them to age- and gender-matched controls. These researchers reviewed multiple patellotrochlear congruence and patellofemoral alignment parameters and demonstrated that all were normalized post-operatively compared to the control group [76••]. This research adds support to the hypothesis that dysplasia occurs most notably in the trochlea, and when corrected, the patella is congruent with the normalized trochlea. This improved congruence could serve not only to improve stability of the joint but also to potentially reduce contact pressures and therefore the risk of osteoarthritis.

The Future of Trochleoplasty

The key to alleviating the concerns surrounding this procedure will be building further knowledge about how to appropriately select the patients who will most benefit from a trochleoplasty. To achieve this, ongoing research must further define and classify the dysplastic trochlea and determine its interaction with other pathoanatomic risk factors. Computer modeling and immersive simulations such as virtual reality may enable predictions of the interactions between various risk factors and allow for patient-specific indications for the addition of concomitant procedures such as trochleoplasty.

Although surgical techniques have advanced significantly since the initial description of trochleoplasty, the use of advanced surgical planning with modalities such as robotics or virtual reality will refine the surgical technique in a patient-specific manner and allow for more precise procedures. The ability to use advanced imaging in concert with platforms such as virtual reality will allow surgeons to plan the exact procedure in 3-dimensions. This will optimize patient outcomes while minimizing the associated risks. The use of training modalities such as simulations and virtual reality will reduce the learning curve associated with new and complex procedures, making them safer and reducing complications [77].

Another area that requires investigation is well-designed trials assessing different approaches to post-operative rehabilitation. There is minimal knowledge about the influence of post-operative weight-bearing, bracing, strengthening, and functional exercise on outcomes following trochleoplasty. Considering the extreme weakness or hypoplastic quadriceps musculature present in some patients with high-grade dysplasia and recurrent patellofemoral instability, investigations of the use of strengthening techniques including electrical muscle stimulation to facilitate rehabilitation are warranted. Validation of return to sport assessment criteria will be another important consideration to optimize outcomes in this patient population.

Finally, valid and reliable disease-specific outcome measures that are sufficiently sensitive to identify differences between groups will be necessary to explore the indications for the addition of trochleoplasty when stabilizing the patellofemoral joint. The use of measures that assess multiple facets of outcome including quality of life, physical symptoms, catastrophizing, kinesophobia, return to sport assessment, and functional testing will further the accuracy of global assessment in these complex patients both pre- and post-operatively.

Conclusion

This review has demonstrated that the use of sulcus-deepening trochleoplasty for the treatment of high-grade dysplasia and recurrent patellofemoral instability is a well-established technique with good outcomes and an acceptable complication profile, similar to that of other patellofemoral stabilization procedures. In patients with high-grade dysplasia, trochleoplasty results in lower re-dislocation rates, high patient satisfaction scores, and good clinical and functional outcomes. An understanding of trochleoplasty and its indications should be in the armamentarium of surgeons treating patellofemoral pathology.

Recent publications on trochleoplasty have been spurred by an improved understanding of the pathology and indications, as well as greater familiarity with available variations in surgical techniques. While there have been some meta-analyses performed in the current literature, a common limitation amongst them is the heterogeneity amongst the studies that limit their value. Allaying concerns about complications will require that future studies have robust inclusion and exclusion criteria as well as standardized reporting of complications and adverse outcomes. The lack of inter-rater agreement for the grading of trochlear dysplasia and untested outcome measures also limits the translation from these research studies to improved clinical decision-making. It is critical for scientific progress that a reliable and valid standardization of the trochlear dysplasia classification is developed as well as disease-specific outcome scores to help guide the treating physician.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

•• Hiemstra LA, Kerslake S, Lafave MR. Quality-of-life outcomes of patients following patellofemoral stabilization surgery: the influence of trochlear dysplasia. J Knee Surg. 2017;30(9):887–93. This paper is the first to follow patients with trochlear dysplasia after MPFL reconstruction, using a disease-specific quality of life measure, to determine the threshold at which patients have poorer outcomes with trochlear dysplasia.

Fithian DC, Paxton EW, Stone ML, Silva P, Davis DK, Elias DA, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of acute patellar dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(5):1114–21.

Hiemstra LA, Kerslake SA, Lafave MR. Influence of risky pathoanatomy and demographic factors on clinical outcomes after isolated medial matellofemoral ligament reconstruction: a regression analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(12):2904–9.

Liu JN, Brady JM, Kalbian IL, Strickland SM, Ryan CB, Nguyen JT, et al. Clinical outcomes after isolated medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction for patellar instability among patients with trochlear dysplasia. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(4):883–9.

Fitzpatrick CK, Steensen RN, Tumuluri A, Trinh T, Bentley J, Rullkoetter PJ. Computational analysis of factors contributing to patellar dislocation. J Orthop Res. 2016;34(3):444–53.

Oye CR, Holen KJ, Foss OA. Mapping of the femoral trochlea in a newborn population: an ultrasonographic study. Acta Radiol. 2015;56(2):234–43.

Glard Y, Jouve JL, Garron E, Adalian P, Tardieu C, Bollini G. Anatomic study of femoral patellar groove in fetus. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(3):305–8.

Dejour H, Walch G, Nove-Josserand L, Guier C. Factors of patellar instability: an anatomic radiographic study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1994;2(1):19–26.

Van Haver A, De Roo K, De Beule M, Labey L, De Baets P, Dejour D, Claessens T, Verdonk P. The effect of trochlear dysplasia on patellofemoral biomechanics: a cadaveric study with simulated trochlear deformities. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(6):1354–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546515572143.

•• Kaiser D, Trummler L, Götschi T, Waibel FWA, Snedeker JG, Fucentese SF. Patellofemoral instability in trochleodysplastic knee joints and the quantitative influence of simulated trochleoplasty - a finite element simulation. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2021;81:105216. This study evaluates patellofemoral instability and the effects of trochleoplasty using a quasi-static finite model. Using MRI, the researchers created a validated model that was able to quantify the force required to lateralize a patella in models with Type B trochlear dysplasia.

Dejour D, Saggin P. The sulcus deepening trochleoplasty-the Lyon’s procedure. Int Orthop. 2010;34(2):311–6.

Carstensen SE, Menzer HM, Diduch DR. Patellar instability: when is trochleoplasty necessary? Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2017;25(2):92–9.

Lippacher S, Dejour D, Elsharkawi M, Dornacher D, Ring C, Dreyhaupt J, et al. Observer agreement on the Dejour trochlear dysplasia classification: a comparison of true lateral radiographs and axial magnetic resonance images. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(4):837–43.

Nelitz M, Lippacher S, Reichel H, Dornacher D. Evaluation of trochlear dysplasia using MRI: correlation between the classification system of Dejour and objective parameters of trochlear dysplasia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(1):120–7.

Nacey NC, Fox MG, Luce BN, Boatman DM, Diduch DR. Assessing femoral trochlear morphologic features on cross-sectional imaging before trochleoplasty: Dejour classification versus quantitative measurement. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;215(2):458–64.

Biedert R, Sigg A, Gal I, Gerber H. 3D representation of the surface topography of normal and dysplastic trochlea using MRI. Knee. 2011;18(5):340–6.

• Ferlic PW, Runer A, Seeber C, Thöni M, Spicher A, Liebensteiner MC. Linear anterior-posterior computed tomography parameters used to quantify trochlear dysplasia are more reliable than angular measurements. Arthroscopy. 2021;37(4):1204–11. This study indicates low reliability of the angular parameters used to quantify trochlear morphology in comparison to linear measurements, as well as lower reliability in patients with PFI.

Albee F. Bone graft wedge in the treatment of habitual dislocation of the patella. Med Rec. 1915;88:257–9.

Masse Y. [Trochleoplasty. Restoration of the intercondylar groove in subluxations and dislocations of the patella]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1978;64(1):3–17.

Schottle PB, Fucentese SF, Pfirrmann C, Bereiter H, Romero J. Trochleaplasty for patellar instability due to trochlear dysplasia: a minimum 2-year clinical and radiological follow-up of 19 knees. Acta Orthop. 2005;76(5):693–8.

Blond L, Schottle PB. The arthroscopic deepening trochleoplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(4):480–5.

Camathias C, Speth BM, Rutz E, Schlemmer T, Papp K, Vavken P, et al. Solitary trochleoplasty for treatment of recurrent patellar dislocation. JBJS Essent Surg Tech. 2018;8(2): e11.

Davies MR, Allahabadi S, Diab TE, Freshman RD, Pandya NK, Feeley BT, et al. Sulcus-deepening trochleoplasty as an isolated or combined treatment strategy for patellar instability and trochlear dysplasia: a systematic review. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2020;2(5):e661–9.

Balcarek P, Rehn S, Howells NR, Eldridge JD, Kita K, Dejour D, et al. Results of medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction compared with trochleoplasty plus individual extensor apparatus balancing in patellar instability caused by severe trochlear dysplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(12):3869–77.

Hiemstra LA, Peterson D, Youssef M, Soliman J, Banfield L, Ayeni OR. Trochleoplasty provides good clinical outcomes and an acceptable complication profile in both short and long-term follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(9):2967–83.

Leclerc JT, Dartus J, Labreuche J, Martinot P, Galmiche R, Migaud H, et al. Complications and outcomes of trochleoplasty for patellofemoral instability: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 1000 trochleoplasties. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2021;10:103035.

Testa EA, Camathias C, Amsler F, Henle P, Friederich NF, Hirschmann MT. Surgical treatment of patellofemoral instability using trochleoplasty or MPFL reconstruction: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(8):2309–20.

Song GY, Hong L, Zhang H, Zhang J, Li X, Li Y, et al. Trochleoplasty versus nontrochleoplasty procedures in treating patellar instability caused by severe trochlear dysplasia. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(4):523–32.

van Sambeeck JDP, van de Groes SAW, Verdonschot N, Hannink G. Trochleoplasty procedures show complication rates similar to other patellar-stabilizing procedures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(9):2841–57.

Longo UG, Vincenzo C, Mannering N, Ciuffreda M, Salvatore G, Berton A, et al. Trochleoplasty techniques provide good clinical results in patients with trochlear dysplasia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(9):2640–58.

• Zaffagnini S, Previtali D, Tamborini S, Pagliazzi G, Filardo G, Candrian C. Recurrent patellar dislocations: trochleoplasty improves the results of medial patellofemoral ligament surgery only in severe trochlear dysplasia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(11):3599–613. Meta-analysis indicating that isolated MPFL reconstruction is as effective as MPFL reconstruction combined with trochleoplasty in the setting of moderate trochlear dysplasia. However, in the setting of severe trochlear dysplasia, combined trochleoplasty with MPFL reconstruction leads to lower redislocation rates.

Tan CMP, Zhu Y, Guo L, Loh SYJ. Medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction with and without trochleoplasty for patients with patella instability-correlation of trochlear dysplasia and patient outcome, classification and outcome measure in the past decade-a systematic review. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2022;32(4):595–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-021-03030-z.

Stupay KL, Swart E, Shubin Stein BE. Widespread implementation of medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction for recurrent patellar instability maintains functional outcomes at midterm to long-term follow-up while decreasing complication rates: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(7):1372–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2014.12.029.

Hiemstra LA, Kerslake S, O’Brien CL, Lafave MR. Accuracy and learning curve of femoral tunnel placement in medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction. J Knee Surg. 2017;30(9):879–86.

• Hiemstra LA, Page JL, Kerslake S. Patient-reported outcome measures for patellofemoral instability: a critical review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2019;12(2):124–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-019-09537-7. A review of the available patient-reported outcome measures for patellofemoral instability including an assessment of their strengths and weaknesses in this patient population.

•• Lafave MR, Hiemstra L, Kerslake S. Factor analysis and item reduction of the Banff Patella Instability Instrument (BPII): introduction of BPII 2.0. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(8):2081–6. The only disease-specific patient-reported outcome measure for patellofemoral instability.

• Smith TO, Donell ST, Clark A, Chester R, Cross J, Kader DF, et al. The development, validation and internal consistency of the Norwich Patellar Instability (NPI) score. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(2):324–35. A disease-specific physical symptom score for patients with patellofemoral instability.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(4):539–49.

Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM, Alonso J, Patrick DL, de Vet HCW, et al. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1147–57.

Wagner D, Pfalzer F, Hingelbaum S, Huth J, Mauch F, Bauer G. The influence of risk factors on clinical outcomes following anatomical medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) reconstruction using the gracilis tendon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(2):318–24.

Hopper GP, Leach WJ, Rooney BP, Walker CR, Blyth MJ. Does degree of trochlear dysplasia and position of femoral tunnel influence outcome after medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction? Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(3):716–22.

Howells NR, Barnett AJ, Ahearn N, Ansari A, Eldridge JD. Medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction: a prospective outcome assessment of a large single centre series. J Bone Joint Surg Br Vol. 2012;94(9):1202–8.

Steiner TM, Torga-Spak R, Teitge RA. Medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction in patients with lateral patellar instability and trochlear dysplasia. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(8):1254–61.

Kita K, Tanaka Y, Toritsuka Y, Amano H, Uchida R, Takao R, et al. Factors affecting the outcomes of double-bundle medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction for recurrent patellar dislocations evaluated by multivariate analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(12):2988–96.

Su P, Liu X, Jian N, Li J, Fu W. Clinical outcomes and predictive factors for failure with MPFL reconstruction combined with tibial tubercle osteotomy and lateral retinacular release for recurrent patellar instability. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):632.

•• Fucentese SF, Zingg PO, Schmitt J, Pfirrmann CW, Meyer DC, Koch PP. Classification of trochlear dysplasia as predictor of clinical outcome after trochleoplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(10):1655–61. This study assessed outcomes of trochleoplasty based on the grade of trochlear dysplasia, demonstrating that only high-grade dysplasia was appropriate for trochleoplasty.

Hiemstra LA, Kerslake S, Loewen M, Lafave M. Effect of trochlear dysplasia on outcomes after isolated soft tissue stabilization for patellar instability. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1515–23.

Rush J, Diduch D. When is trochleoplasty a rational addition? Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2019;27(4):161–8.

Balcarek P, Oberthur S, Hopfensitz S, Frosch S, Walde TA, Wachowski MM, et al. Which patellae are likely to redislocate? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(10):2308–14.

Lewallen L, McIntosh A, Dahm D. First-time patellofemoral dislocation: risk factors for recurrent instability. J Knee Surg. 2015;28(4):303–9. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1398373.

Hiemstra L, Kerslake S. Failed medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction: causes and treatment. In: Parikh S, editor. patellar instability and dislocation: classification and operative techniques. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Inc; 2019. p. 440–53.

Dejour DH. Editorial commentary: trochleoplasty: is it really that fearsome and dangerous a technique? Arthroscopy. 2020;36(8):2246–8.

•• Carstensen SE, Feeley SM, Burrus MT, Deasey M, Rush J, Diduch DR. Sulcus deepening trochleoplasty and medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction for patellofemoral instability: a 2-year study. Arthroscopy. 2020;36(8):2237–45. A large recent case series of trochleoplasty and MPFL reconstruction that reported safety and efficacy of the procedure in the primary and the revision setting.

• Nelitz M, Dreyhaupt J, Williams SRM. No growth disturbance after trochleoplasty for recurrent patellar dislocation in adolescents with open growth plates. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(13):3209–16. The first study to assess trochleoplasty in skeletally immature patients, demonstrating safety in the adolescent patient with less than 2 years of growth remaining.

Southam BR, Colosimo AJ, Grawe B. Underappreciated factors to consider in revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a current concepts review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(1):2325967117751689.

•• Metcalfe AJ, Clark DA, Kemp MA, Eldridge JD. Trochleoplasty with a flexible osteochondral flap: results from an 11-year series of 214 cases. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B(3):344–50. Largest case series of thin flap trochleoplasty to date, demonstrating good clinical results and an acceptable complication rate.

Blond L, Haugegaard M. Combined arthroscopic deepening trochleoplasty and reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament for patients with recurrent patella dislocation and trochlear dysplasia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(10):2484–90.

Nelitz M, Williams RS, Lippacher S, Reichel H, Dornacher D. Analysis of failure and clinical outcome after unsuccessful medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction in young patients. Int Orthop. 2014;38(11):2265–72.

Zimmermann F, Milinkovic DD, Börtlein J, Balcarek P. Revision surgery for failed medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction results in better disease-specific outcome scores when performed for recurrent instability than for patellofemoral pain or limited range of motion. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2022;30(5):1718–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-021-06734-1.

Zimmermann F, Börtlein J, Milinkovic DD, Balcarek P. Patient-reported outcomes after revision surgery for failed medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction: a matched-pair analysis including correction of predisposing factors. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48(14):3566–72.

Dejour D, Byn P, Ntagiopoulos PG. The Lyon’s sulcus-deepening trochleoplasty in previous unsuccessful patellofemoral surgery. Int Orthop. 2013;37(3):433–9.

Paley D, Herzenberg JE, Tetsworth K, McKie J, Bhave A. Deformity planning for frontal and sagittal plane corrective osteotomies. Orthop Clin North Am. 1994;25(3):425–65.

• Biedert RM. Combined deepening trochleoplasty and supracondylar external rotation osteotomy for recurrent patellar instability in patients with trochlear dysplasia and increased femoral antetorsion. Knee. 2020;27(4):1158–66. Reported series of patients that underwent simultaneous trochleoplasty and femoral external derotation osteotomy in the setting of femoral anteversion with good post-operative outcomes.

Nelitz M, Dreyhaupt J, Williams SR, Dornacher D. Combined supracondylar femoral derotation osteotomy and patellofemoral ligament reconstruction for recurrent patellar dislocation and severe femoral anteversion syndrome: surgical technique and clinical outcome. Int Orthop. 2015;39(12):2355–62.

Seitlinger G, Scheurecker G, Hogler R, Labey L, Innocenti B, Hofmann S. Tibial tubercle-posterior cruciate ligament distance: a new measurement to define the position of the tibial tubercle in patients with patellar dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1119–25.

Fucentese SF, Schottle PB, Pfirrmann CW, Romero J. CT changes after trochleoplasty for symptomatic trochlear dysplasia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(2):168–74.

Vogel LA, Pace JL. Trochleoplasty, medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction, and open lateral lengthening for patellar instability in the setting of high-grade trochlear dysplasia. Arthrosc Tech. 2019;8(9):e961–7.

Levy BJ, Tanaka MJ, Fulkerson JP. Current concepts regarding patellofemoral trochlear dysplasia. Am J Sports Med. 2021;49(6):1642–50.

Biedert RM, Albrecht S. The patellotrochlear index: a new index for assessing patellar height. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(8):707–12.

Rouanet T, Gougeon F, Fayard JM, Rémy F, Migaud H, Pasquier G. Sulcus deepening trochleoplasty for patellofemoral instability: a series of 34 cases after 15 years postoperative follow-up. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101(4):443–7.

Neumann MV, Stalder M, Schuster AJ. Reconstructive surgery for patellofemoral joint incongruency. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(3):873–8.

Ntagiopoulos PG, Byn P, Dejour D. Midterm results of comprehensive surgical reconstruction including sulcus-deepening trochleoplasty in recurrent patellar dislocations with high-grade trochlear dysplasia. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(5):998–1004.

Jungmann PM, Tham SC, Liebl H, Nevitt MC, McCulloch CE, Lynch J, et al. Association of trochlear dysplasia with degenerative abnormalities in the knee: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(10):1383–92.

Ali SA, Helmer R, Terk MR. Analysis of the patellofemoral region on MRI: association of abnormal trochlear morphology with severe cartilage defects. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(3):721–7.

Falkowski AL, Camathias C, Jacobson JA, Magerkurth O. Increased magnetic resonance imaging signal of the lateral patellar facet cartilage: a functional marker for patellar instability? Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(10):2276–83.

•• Balcarek P, Zimmermann F. Deepening trochleoplasty and medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction normalize patellotrochlear congruence in severe trochlear dysplasia. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-B(3):325–30. Using MRI post trochleoplasty this study demonstrated that after surgery the patients had normalized patellotrochlear congruence and patellofemoral alignment parameters compared to control.

Lohre R, Bois AJ, Athwal GS, Goel DP, (CSES) CSaES. Improved complex skill acquisition by immersive virtual reality training: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102(6):e26.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Magdalena Tarchala, Sarah Kerslake, and Laurie Hiemstra declare that they have no conflict of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tarchala, M., Kerslake, S. & Hiemstra, L.A. Sulcus-Deepening Trochleoplasty for High-Grade Trochlear Dysplasia: Demystifying the Procedure—a Review of the Current Literature. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 16, 538–549 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-023-09868-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-023-09868-6