Abstract

Purpose

Prospectively, a consecutive group of patients troubled by recurrent patella dislocation and trochlear dysplasia has been followed after a combined arthroscopic deepening trochleoplasty and reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament. The purpose of this follow-up study is to report the clinical results.

Methods

Indications for combined arthroscopic deepening trochleoplasty and reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament were two or more patellar dislocations with a persistent apprehension sign above 20° of flexion and trochlear dysplasia grade B or more. Prospectively, the Tegner, Kujala and KOOS scores were recorded. Thirty-one consecutive patients (37 knees), 21 women and 10 men, with a median age of 19 (12–39) underwent the procedure.

Results

Results were obtained for 29 knees with a minimum of 12-month follow-up (average 29 months; range 12–57). No complications, redislocations or arthrofibrosis have been recorded. Five patients needed further surgery. The median pre- and postoperative scores (range) are as follows: Kujala 64 (12–90) to 95 (47–100); Tegner 4 (1–6) to 6 (4–9); KOOS score pain 86–94; symptoms 82–86; ADL 91–99; sport 40–86; QDL 25–81. No significant correlation was found with respect to the results and recorded parameters. Significant improvement for all of the scores was observed (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

The use of arthroscopic deepening trochleoplasty in combination with reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament was found to be a safe and reproducible procedure. Considering the stability achieved, the knee scores and the patient’s level of satisfaction, the results are encouraging.

Level of evidence

Prospective consecutive case series, with evaluation of confounding factor. No control group, Level IV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recurrent patella dislocation (RPD) is a disabling condition, where patients feel insecure on their affected knee and some also experience pain. In many cases, this leads to a decreased level of activity and a reduced quality of daily living [34, 43]. Various anatomical factors, either alone or in combination, reduce containment of the patella in the trochlear groove, which predisposes for patella dislocation. Subsequent studies have supported the fact that the single most important factor for RPD is trochlear dysplasia (TD); however, patella alta, and rotational and angular bony alignments are also important factors for stressing the soft tissue stabilisers and finally cause them to fail [12, 19, 22, 33, 35]. A biomechanical study found that simulated TD reduced the lateral stability of the patella significantly when compared with normal knees, and that trochleoplasty increased the stability to a level that was not significantly different from that of the normal knee [1]. Increased patellofemoral (PF) joint forces associated with a flattened proximal trochlear groove have been correlated with cartilage wear in a study by Teichtal et al. [47]. Moreover, TD has been associated with the development of osteoarthritis in the PF joint [25, 30], and Keser et al. [31] further correlated TD with patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS). Given these findings, the open deepening trochleoplasty (DT) has become a more widespread and accepted solution in cases with RPD having TD, and several case series have found positive results with this procedure [17, 20, 21, 32, 41, 51, 52]. The main idea of the DT is to reduce the patellofemoral joint forces by creating a more congruent joint with improved bony stability and better containment of the patella. The DT alone only provides minor stability for the patella in full extension, contrary to the medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction (MPFLR) technique, which provides stability in the whole range of movement. Today, the most common techniques for open DTs are the Dejour technique [18], the Bereiter-Gautier technique [4] and Goutallier recession trochleoplasty [23, 24, 48]. Personal experiences of performing open DTs [9] are based on the Bereiter-Gautier technique, and the results are similar to previous studies [32, 41]. However, there are concerns regarding the extent of the open operation with respect to pain and scar formation and, furthermore, it is well recognised that open procedures are related to an increased risk of infection and arthrofibrosis [52]. A pilot study from Blond and Schöttle used an arthroscopic technique for a DT in combination with MPFLR and demonstrated promising results concerning postoperative pain and scar formation [8]. The purpose of this follow-up study is to report the clinical results from the first prospective and consecutive series of arthroscopic deepening trochleoplasty (ADT) in combination with MPFLR in patients with recurrent patella instability and TD.

Materials and Methods

The inclusion criteria used were patients with RPD and TD type B to D, according to the classification of Tecklenburg et al. [46]. In addition, a positive patella apprehension sign at a minimum of 20° flexion was mandatory. Patients were included consecutively and followed up prospectively. All operations were performed by the same experienced arthroscopic surgeon, starting with the surgeons very first ADT. Between 2008 and 2011, 37 combined ADT and MPFLR procedures were carried out in 31 consecutive patients (6 bilateral), 21 female and 10 male. Sixteen of these knees have previously undergone stabilising procedures without success, and among these combined lateral release and medial imbrication was most frequently represented, however, also tuberosity tibia medialisation (TT) and MPFL re-insertion had been utilised. According to the respective descriptions, the following radiographic parameters were measured by radiographs and MRI, tibial tubercle to trochlear groove distance (TTTG) [40], lateral condyle index [6], lateral trochlear inclination (LTI) [12].In respect to the patella height, the following ratios or indices of Insall-Salvati [28], Blackburne-Peel [7], Caton–Deschamps [13] and patellotrochlear index [5] were measured. The trochlear asymmetry was measure 3 cm above joint line according to Pfirmann et al. [39].The cartilage status was evaluated by arthroscopy and graded in four classes by the use of I.C.R.S. classification. All patients were available for follow-up. Twenty-four patients (29 knees) with a minimum of a 12-month follow-up were included in the figures and the statistics. Patients fulfilled the KOOS score, the Tegner score and the Kujala score pre- and postoperatively, and a supplement of questionnaire published by Utting, Mulford and Eldrige was applied at the last follow-up [51]. Two observers, both specialists in orthopaedic surgery with a special interest in the patellofemoral joint evaluated all of the patients pre- and postoperatively. See Table 1.

Surgical technique

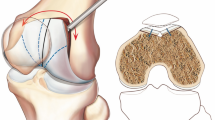

Arthroscopic deepening trochleoplasty (ADT) is based on the Bereiter-Gautier technique and was performed in accordance with the description by Blond and Schöttle [8]. A standard diagnostic arthroscopy was performed, followed by the establishment of suprapatellar portals, through which the cartilage in the proximal part of the trochlear was released using a round burr shaver, and the bony part of the trochlear was deepened and lateralised. Next, the cartilage flake was reinserted with resorbable vicryl tapes and suture anchors (see Fig. 1). For the MPFLR, an autologous gracilis tendon was used as graft. This was performed in a double bundle technique with a proximal and distal bundle at the patellar insertion, following by fixation of the graft using an absorbable interference screw in a bone tunnel immediately distal to the isometric femoral insertion point after dynamic testing. In this way, a desired anisometry for the reconstruction was achieved, so the new ligament became tight in extension and relatively slack in flexion as described by Thaunat and Erasmus [50]. In cases with open epiphyses, the femoral insertion of the graft was fixed with a sling around the adductor magnus tendon, in order to avoid damage of the epiphyses [2]. All patients were operated on using spinal anaesthesia. Pre- and postoperatively, 20 ml of 0.5 % bupivacaine and epinephrine was distributed in the incisions and intra-articular regions. In order to optimise visualisation, the tourniquet needed to be inflated in one of the cases due to minor bleeding. Postoperative full weight bearing was allowed immediately after surgery, while a knee brace with a limited extension of 30° but free flexion was prescribed for 2 weeks. Following this, a full range of motion was sought. Postoperatively, all patients had knee stabilising training for a period of about 12 weeks, guided by various external physiotherapists. All patients left the hospital on the same day or the morning after surgery.

Statistical analysis

Pre- and postoperative clinical findings were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Spearman’s rho test was used for the correlation between different outcome parameters and demographic data. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical standards

The local Ethics Committee of Copenhagen approved the study H–C-2009-010 (nr 21296), and it was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave their informed consent to participate in the study.

Results

At follow-up examination, all knees had regained the preoperative range of movements, and the patella apprehension sign was not found by the observers. No re-dislocations, infections, cartilage flake breakage or necrosis were registered. Median follow-up 29 month range (12–57). The median (range) Kujala score increased from 64 (12–90) to 95 (47–100), and the Tegner score increased from 4 (1–6) to 6 (4–9). Median (range) KOOS score pain pre: 86 (42–97), post: 94 (53–100); symptoms pre: 82 (32–100), post: 86 (57–100); ADL pre: 91 (31–99), post: 99 (69–100); sports pre: 40 (0–95), post: 85 (20–100); QDL pre: 25 (0–69), post: 75 (25–100). See Fig. 2. For the supplementary questionnaire, see Table 2. For second look arthroscopy examples, see Fig. 3. Two patients developed symptomatic subluxations 28 months postoperatively, and their J-sign relapsed simultaneously. Their postoperative MRI showed acceptable trochleoplasties and correct insertion at the femur site of their MPFLR; however, these knees were characterised as the two knees with the highest TTTG distances, that is, 28 and 40 mm. Both were subsequently corrected by medialisation of the tibial tubercle (TT), and their subluxations stopped. Three patients experienced pronounced postoperative anterior knee pain at flexion. On examination, tightness of the lateral retinaculum was found, indicating lateral hyper-pressure syndromes. These patients subsequently had lateral releases and responded with decreased pain. No significant correlations were found between the postoperative results with respect to the knee scores and the demographic data, age, time from first dislocation, previous surgery, Dejour Classification, radiologic parameters or length of follow-up. Significant improvement in Kujala score, Tegner score and the five subgroups in the KOOS score (p < 0.001) was observed.

Discussion

The most important finding in the present follow-up study of the combined ADT and MPFL procedure is that it is a reproducible and safe technique for stabilising the patella, as significant improvements for all measured knee scores were observed. Five patients did not achieve acceptable results and needed further surgery. Two patients were characterised as having the highest TTTG index in the series and developed subluxations 28 months postoperatively. It is hypothesised that the high lateral vector forces caused this. In both cases, the patient responded successfully after supplementary TT procedures, indicating that this should have been executed simultaneously with the ADT and MPFL reconstruction. As a result, a supplementary TT is now always considered when the TTTG distance exceeds 20 mm. Three patients developed lateral hyper-pressure syndrome and, in these cases, the preoperative coronal MRI scans showed lateral displacement and tilt of the patellae. These patients responded positively on supplementary lateral release. Christoforakis et al. [15] found that lateral release increases instability, and this procedure has previously been restricted based on those findings. From personal experience, it can now be seen that a supplementary lateral release can be indicated at the end of the ADT and MPFLR procedure in selected cases, which is in accordance with the approach of Furentese et al. [21].

Questions have been raised regarding the necessity of doing a trochleoplasty, when the patella can be sufficiently stabilised by doing an MPFLR alone. In a recent study by Wagner et al. [53], a negative relationship was found between the degree of TD and outcome after MPFL reconstruction, and they emphasised that a concomitant trochleoplasty or TT should be considered in cases with type III TD. This group obtained a mean Kujala score of 79 in the subgroup of TD grade III. Steiner et al. [45], however, did not see a relationship between the results of MPFL reconstruction and TD. In a group of 41 patients, 34 had TD, 19 of which were patients with patella dislocations, and the rest were distributed among patients with subluxation and with pain. Further weaknesses in their study were that 3 surgical techniques were used, the lack of a clinical follow-up examination and no data on the distribution of the types of dysplasia. When stabilising the patella by an MPFLR solely, the main aetiology for the instability is not addressed. RPD patients can often recall a period of subluxation, before their actual patella dislocation occurred. It is hypothesised that their native MPFL was stressed over time until the native MPFL suddenly ruptured and the patella dislocated concomitantly. MPFLR with an appropriate graft is able to give these patients a stronger ligament compared with the native ligament, and the patella is also stabilised, but the lack of bony stability is not addressed. The stress force of the reconstructed MPFL ligament is likely to result in higher joint reaction forces to the cartilage in the patellofemoral joint. In respect to patella cartilage wear, Teichtal et al. observed a strong correlation between amount of wear and a flat trochlear, which corresponds to the findings by Stefanik et al. and Kalichman et al., who observed a strong association between a low trochlear inclination angle (TD) and the development of osteoarthritis [30, 44]. Keser et al. compared LTI in two groups of patient with PFPS and a group of menisci tears. In 75 % of the PFPS group, the LTI was below 20, and in 85 % of the menisci group, the LTI was over 20) [31]. Goutallier et al. described a series of 12 patients with a 4-year follow-up and demonstrated promising results with open deepening trochleoplasty as a surgical solution for patients troubled by PFPS and TD without a history of instability [24, 31]. Based on these findings, it can be hypothesised that although the EPS patients can be stabilised with an MPFLR, an addition of a concomitant trochleoplasty will reduce the joint forces and subsequently reduce the pain and the cartilage wear. Against this hypothesis is the study by Nomura et al., which was a long-term follow-up study 11.9 years after MPFLR using a polyester tape, and only found minor osteoarthritic changes [50]. However, in this study, the number of patients with TD was not specified [38].

Subsequent studies have reported good outcomes from MPFLR solely or in combination with TT, but in the review by Fisher et al. they reported that in 18 out of 21 studies (equalling 155 out of 510 patients), a diversity of problems or complications were found at follow-up [10, 49]. Christiansen et al. observed palpable pain at the medial patellar edge in 43 % of the patients (19/44) and at the medial femoral condyle in 50 % (22/44) in their follow-up after MPFLR, suggesting that the increased medial forces on the MPFL could be the main aetiology of that pain [14]. This is supported by one patient in the current series who had undergone a successful ADT and MPFLR procedure in the right knee based on the inclusion criteria above. However, she was also troubled by RPD in the contralateral knee and had a grade A TD and normal TTTG distance. According to the indications of this study, she only had an MPFLR in her left knee. Postoperatively, she experienced minor to medium adductor side pain in the left knee for more than a year, opposed to her contralateral knee, which was pain free.

In a study by Christiansen et al. [14], a subgroup of 12 patients with both TD grade B–D and RPD had a combined TT and MPFLR. In this subgroup, a median Kujala score of 83 was obtained. An argument against doing the combined TT and MPFLR was that, in respect to pain and development of osteoarthritis, long-term follow-up studies have found deteriorating results [11, 36] and corresponding results have been observed for the Hauser [3, 16, 26, 29] and Goldthwait procedures [42].

With respect to the KOOS score, the patients in this series obtained significant improvement for all five subgroups and considerable gains in sports and recreational activities, as well as for quality of life (QOL). In addition, good results according to the postoperative Kujala scores and Tegner scores were observed. Bearing in mind that these patients do not represent a standard cohort of recurrent patella instability, but the more severe cases with Dejour dysplasia grade B–D and revision cases, it is thought that the results from this series are very encouraging. It must be emphasised that direct comparison with other follow-up studies from trochleoplasty procedures and MPFLR is difficult because of the differences in patients, inclusion criteria and outcome measures. The outcomes measures for patients with RPD are rarely validated and more precise scores based on items analysis are not yet available.

Fucentese et al. observed better results in patients having Dejour type B or D compared with type A and C in a follow-up after open trochleoplasty [21]. These findings were not reproduced in this study, perhaps due to the low number of patients in the series. Two patients in the current series had open growth plates; however, in both cases, the patients had menstruated for a minimum of 1 year, so the risk of growth disturbances was considered to be minor, and no unintended closures of the epiphysis have been registered on subsequent MRI scans. Based on the studies by Huri et al. [27] and Nelitz et al. [37], it can be considered that early intervention is of importance for the knee to adapt to the normalisation of anatomy.

Several limitations of this study have to be taken into account. The minimum follow-up is only 1 year, and the two observers were dependent. No validated score for patellofemoral instability was used, and no control group was included. There was a lack of systematic evaluation of the femoral rotation. All patients in this series, starting with the very first ADT, were consecutively performed by the same surgeon, but the surgeon’s skills for the combined ADT and MPFLR procedure were refined through the series, and the learning curve is an unknown factor. The follow-up time was short, and although the last two knees were not included in the figures and statistics, some of the results were discussed.

We conclude that in day-to-day clinical work, this procedure has an advantage in comparison with the open trochleoplasty, because it appears to be faster and technically easier. Moreover, it can be done as same-day surgery.

Conclusion

Arthroscopic deepening trochleoplasty (ADT) in combination with MPFLR in cases with recurrent patella instability and TD is a safe and reproducible procedure. However, concomitant procedures, such as the medialisation of the tibial tubercle or lateral release, will be indicated in selected cases. When TD is present, the trochleoplasty aims to normalise anatomy in a more tailored approach than previously used methods. Corresponding to other surgical procedures showing a benefit from minimally invasive techniques, it is concluded that the arthroscopic technique is superior to the open technique with respect to the level of postoperative pain, scar formation, length of rehabilitation, and risks of infection and arthrofibrosis. Surprisingly, the arthroscopic technique appears to be easier and a more precise technique relative to the open technique. Based on the knee scores, it is believed that a combined ADT and MPFLR for patients troubled by RPD is a promising procedure for the future.

References

Amis A, Oguz C, Bull A, Senavongse W, Dejour D (2008) The effect of trochleoplasty on patellar stability and kinematics: a biomechanical study in vitro. J Bone Joint Surg Br 90:864–869

Arendt EA (2010) MPFL Reconstruction: The Adductor Sling Approach. In: Zaffagnini S, Dejour D, Arendt EA (eds) Patellofemoral pain, instability, and arthritis. Springer, Berlin, pp 175–179

Barbari S, Raugstad TS, Lichtenberg N, Refvem D (1990) The Hauser operation for patellar dislocation. 3–32-year results in 63 knees. Acta Orthop Scand 61:32–35

Bereiter H, Gautier E (1994) Die trochleaplastik als Chirurgische therapie der Reziderenden patellaluxation bei trochleadysplasie. Arthroskopie 7:281–286

Biedert RM, Netzer P, Gal I, Sigg A, Tscholl PM (2011) The lateral condyle index: a new index for assessing the length of the lateral articular trochlea as predisposing factor for patellar instability. Int Orthop 35:1327–1331

Biedert RM, Albrecht S (2006) The patellotrochlear index: a new index for assessing patellar height. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 14:707–712

Blackburne JS, Peel TE (1977) A new method of measuring patellar height. J Bone Joint Surg Br 59:241–242

Blønd L (2009) Prospective evaluation of open trochleoplasty in patients with recurrent patella dislocation and severe trochlea dysplasia. Danish association of orthopaedics annual meeting http://www.ortopaedi.dk/fileadmin/bulletin/DOS%20nr.%203%20%202009-netbrug.pdf

Blønd L, Schöttle PB (2010) The arthroscopic deepening trochleoplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 18:480–485

Buckens C, Saris D (2010) Reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament for treatment of patellofemoral instability: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med 38:181–188

Carney JR, Mologne TS, Muldoon M, Cox JS (2005) Long-term evaluation of the Roux-Elmslie-Trillat procedure for patellar instability: a 26-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 33:1220–1223

Carrillon Y, Abidi H, Dejour D, Fantino O, Moyen B, Tran-Minh VA (2000) Patellar instability: assessment on MR images by measuring the lateral trochlear inclination-initial experience. Radiology 216:582–585

Caton J, Deschamps G, Chambat P, Lerat JL, Dejour H (1982) Patella infera. apropos of 128 cases. Rev Chir Orthop 68:317–325

Christiansen SE, Jacobsen BW, Lund B, Lind M (2008) Reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament with gracilis tendon autograft in transverse patellar drill holes. Arthroscopy 24:82–87

Christoforakis J, Bull AM, Strachan RK, Shymkiw R, Senavongse W, Amis AA (2006) Effects of lateral retinacular release on the lateral stability of the patella. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 14:273–277

Crosby EB, Insall J (1976) Recurrent dislocation of the patella. Relation of treatment to osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 58:9–13

Dejour D, Saggin P (2010) The sulcus deepening trochleoplasty-the Lyon’s procedure. Int Orthop 34:311–316

Dejour H, Walch G, Neyret P, Adeleine P (1990) Dysplasia of the femoral trochlea. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 76:45–54

Dejour H, Walch G, Nove-Josserand L, Guier C (1994) Factors of patellar instability: an anatomic radiographic study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2:19–26

Donell ST, Joseph G, Hing CB, Marshall TJ (2006) Modified Dejour trochleoplasty for severe dysplasia: operative technique and early clinical results. Knee 13:266–273

Fucentese SF, Zingg PO, Schmitt J, Pfirrmann CW, Meyer DC, Koch PP (2011) Classification of trochlear dysplasia as predictor of clinical outcome after trochleoplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 19:1655–1661

Galland O, Walch G, Dejour H, Carret JP (1990) An anatomical and radiological study of the femoropatellar articulation. Surg Radiol Anat 12:119–125

Gougeon F, Vanovermeire P, Migaud H, Debroucker MJ, Spiers A, Duquennoy A (1996) Resultats aprés 3 ans de recul de 51 trochléoplasties pour instabilité frontale fémoropatellaire. Rev Chir Orthop 87:85–86

Goutallier D, Raou D, Van Driessche S (2002) Retro-trochlear wedge reduction trochleoplasty for the treatment of painful patella syndrome with protruding trochleae. Technical note and early results. Rev Chir Orthop 88:678–685

Grelsamer RP, Dejour D, Gould J (2008) The pathophysiology of patellofemoral arthritis. Orthop Clin N Am 39:269–274

Hampson WG, Hill P (1975) Late results of transfer of the tibial tubercle for recurrent dislocation of the patella. J Bone Joint Surg Br 57:209–213

Huri G, Atay OA, Ergen B, Atesok K, Johnson DL, Doral MN (2012) Development of femoral trochlear groove in growing rabbit after patellar instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 20:232–238

Insall J, Salvati E (1971) Patella position in the normal knee joint. Radiology 101:101–104

Juliusson R, Markhede G (1984) A modified Hauser procedure for recurrent dislocation of the patella. A long-term follow-up study with special reference to osteoarthritis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 103:42–46

Kalichman L, Zhang Y, Niu J, Goggins J, Gale D, Felson DT, Hunter D (2007) The association between patellar alignment and patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis features—an MRI study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 46:1303–1308

Keser S, Savranlar A, Bayar A, Ege A, Turhan E (2008) Is there a relationship between anterior knee pain and femoral trochlear dysplasia? Assessment of lateral trochlear inclination by magnetic resonance imaging. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 16:911–915

Von Knoch F, Bohm T, Burgi ML, Von Knoch M, Bereiter H (2006) Trochleoplasty for recurrent patellar dislocation in association with trochlear dysplasia. A 4- to 14-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 88:1331–1335

Maenpaa H, Lehto MU (1996) Patellar dislocation has predisposing factors. A roentgenographic study on lateral and tangential views in patients and healthy controls. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 4:212–216

Meidinger G, Tecklenburg K, Fink C, Hoser C (2011) Sports activity seven years after primary patellar dislocation. Arthroscopy 27:e141–e142

Monk AP, Doll HA, Gibbons CL, Ostlere S, Beard DJ, Gill HL, Murray DW (2011) The patho-anatomy of patellofemoral subluxation. J Bone Joint Surg Br 93:1341–1347

Nakagawa K, Wada Y, Minamide M, Tsuchiya A, Moriya H (2002) Deterioration of long-term clinical results after the Elmslie-Trillat procedure for dislocation of the patella. J Bone Joint Surg Br 84:861–864

Nelitz M, Theile M, Dornacher D, Wolfle J, Reichel H, Lippacher S (2012) Analysis of failed surgery for patellar instability in children with open growth plates. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 20:822–828

Nomura E, Inoue M, Kobayashi S (2007) Long-term follow-up and knee osteoarthritis change after medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction for recurrent patellar dislocation. Am J Sports Med 35:1851–1858

Pfirrmann CW, Zanetti M, Romero J, Hodler J (2000) Femoral trochlear dysplasia. Radiology 3:858–868

Schoettle PB, Zanetti M, Seifert B, Pfirrmann CW, Fucentese SF, Romero J (2006) The tibial tuberosity-trochlear groove distance; a comparative study between CT and MRI scanning. Knee 13:26–31

Schottle PB, Fucentese SF, Pfirrmann C, Bereiter H, Romero J (2005) Trochleaplasty for patellar instability due to trochlear dysplasia: a minimum 2-year clinical and radiological follow-up of 19 knees. Acta Orthop 76:693–698

Sillanpaa PJ, Mattila VM, Visuri T, Maenpaa H, Pihlajamaki H (2011) Patellofemoral osteoarthritis in patients with operative treatment for patellar dislocation: a magnetic resonance-based analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 19:230–235

Smith TO, Donell ST, Chester R, Clark A, Stephenson R (2011) What activities do patients with patellar instability perceive makes their patella unstable? Knee 18:333–339

Stefanik JJ, Roemer FW, Zumwalt AC, Zhu Y, Gross KD, Lynch JA, Frey-Law LA, Lewis CE, Guermazi A, Powers CM, Felson DT (2012) Association between measures of trochlear morphology and structural features of patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis on MRI: the most study. J Orthop Res 30:1–8

Steiner TM, Torga-Spak R, Teitge RA (2006) Medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction in patients with lateral patellar instability and trochlear dysplasia. Am J Sports Med 34:1254–1261

Tecklenburg K, Dejour D, Hoser C, Fink C (2006) Bony and cartilaginous anatomy of the patellofemoral joint. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 14:235–240

Teichtahl AJ, Hanna F, Wluka AE, Urquhart DM, Wang Y, English DR, Giles GG, Cicuttini FM (2012) A flatter proximal trochlear groove is associated with patella cartilage loss. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44:496–500

Thaunat M, Bessiere C, Pujol N, Boisrenoult P, Beaufils P (2011) Recession wedge trochleoplasty as an additional procedure in the surgical treatment of patellar instability with major trochlear dysplasia: early results. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 97:833–845

Thaunat M, Erasmus PJ (2008) Recurrent patellar dislocation after medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 16:40–43

Thaunat M, Erasmus PJ (2007) The favourable anisometry: an original concept for medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction. Knee 14:424–428

Utting MR, Mulford JS, Eldridge JDJ (2008) A prospective evaluation of trochleoplasty for the treatment of patellofemoral dislocation and instability. J Bone Joint Surg Br 90:180–185

Verdonk R, Jansegers E, Stuyts B (2005) Trochleoplasty in dysplastic knee trochlea. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 13:529–533

Wagner D, Pfalzer F, Hingelbaum S, Huth J, Mauch F, Bauer G (2013) The influence of risk factors on clinical outcomes following anatomical medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) reconstruction using the gracilis tendon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 21:318–324

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blønd, L., Haugegaard, M. Combined arthroscopic deepening trochleoplasty and reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament for patients with recurrent patella dislocation and trochlear dysplasia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 22, 2484–2490 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-013-2422-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-013-2422-2