Abstract

Recommendations for the management of hypertension in the elderly are largely consistent with the exception of the 2013 Joint National Committee (JNC) 8 guidelines that recommend lowering systolic blood pressure (SBP) in persons aged ≥60 years to <150 mmHg if they do not have diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease. In contrast, I concur with the minority view from JNC 8 which recommends a SBP goal in these persons aged 60 to 79 years of <140 mmHg. This view is consistent with the 2011 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines that also recommend a SBP goal of 140 to 145 mmHg if tolerated in adults aged ≥80 years. ACC/AHA consensus guidelines use the totality of evidence in addition to randomized controlled trial data. These guidelines are also consistent with treatment recommendations from numerous other societies that recommend SBP goals of <140 mmHg in persons aged 60 to 79 years and <150 mmHg in persons aged ≥80 years. Hypertension is currently under-treated in the elderly, and relaxation of ACC/AHA guidelines by JNC 8 will result in substantially more cardiovascular events. Randomized clinical trial studies on treatment of essential hypertension or secondary hypertension in frail elderly persons have not been performed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A consensus document on the management of hypertension in the elderly was published in 2011 by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) in association with the American Academy of Neurology, the American Geriatrics Society, the American Society for Preventive Cardiology, the American Society of Hypertension (ASH), the American Society of Nephrology, the Association of Black Cardiologists (ABC), and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) or European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Based on the strength of both clinical trial data and observational data, this document recommended that the systolic blood pressure (SBP) be lowered to less than 140 mmHg in persons aged 60–79 years and to 140 to 145 mmHg if tolerated in persons aged 80 years and older [1••].

These recommendations are strongly supported by clinical trial data, especially from the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly trial [2–4] and from the Hypertension in the Very Elderly trial (HYVET) [5]. In HYVET, 3845 patients aged 80 years and older (mean age 83.6 years) with a systolic blood pressure of 160 mmHg were randomized to indapamide with perindopril added if needed or to placebo [5]. The average blood pressure achieved in the treatment arm was 143 mmHg. At 1.8-year median follow-up, compared with placebo, antihypertensive drug therapy reduced fatal or nonfatal stroke by 30 % (p = 0.06), fatal stroke by 39 % (p = 0.05), all-cause death by 21 % (p = 0.02), cardiovascular death by 23 % (p = 0.06), and heart failure by 64 % (p < 0.001) [5].

The consensus ACC/AHA guidelines additionally state that the choice of antihypertensive drug therapy in elderly patients depends on efficacy, tolerability, presence of specific comorbidities, and cost [1••]. In support of this recommendation, a meta-analysis of 147 randomized trials of 464, 000 persons with hypertension found that except for the major benefit of beta blocker use following myocardial infarction and a minor benefit of calcium channel blockers (CCBs) in reducing stroke, all major antihypertensive drug classes including diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), beta blockers, and CCBs cause a similar decrease in coronary events and stroke for a given reduction in blood pressure [6].

The guidelines for management of hypertension from the Joint National Committee (JNC) 8 in contrast recommend lowering systolic blood pressure in persons aged ≥60 years to <150 mmHg rather than <140 mmHg if they do not have diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease. However, this recommendation to relax blood pressure control in the elderly is not supported by minority views from JNC 8 or by previous recommendations by ACC/AHA, ESH/ESC, ASH/International Society of Hypertension, and others. The totality of data, including that from both randomized controlled trials and observational studies, supports more aggressive blood pressure control than recommended by JNC 8 in older persons who are not frail.

Recommendations of Other Hypertension Guidelines

With the exception of JNC 8, guidelines recommend that systolic blood pressure be controlled to less than 140 mmHg in persons aged 60 to 79 years. For example, the ESH/ESC 2013 guidelines for management of hypertension recommend lowering the systolic blood pressure to less than 140 mmHg in persons aged 60 to 79 years [7••]. In persons aged 80 years and older with a systolic blood pressure of 160 mmHg or higher, the systolic blood pressure should be lowered to between 140–150 mmHg provided they are in good physical and mental conditions [7••]. These guidelines recommend using diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta blockers, and CCBs as antihypertensive drug therapy in elderly persons. However, diuretics and CCBs may be preferred for treatment of isolated systolic hypertension [7••].

The 2013 JNC 8 guidelines for management of hypertension recommend lowering the systolic blood pressure in persons aged 60 years or older to less than 150 mmHg if they do not have diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease and to less than 140 mmHg if they have diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease [8••]. A minority view from JNC 8 recommends that the systolic blood pressure goal in persons aged 60 to 79 years with hypertension without diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease should be lowered to less than 140 mmHg [9••]. JNC 8 recommends as initial antihypertensive drug therapy in the general non-Black population including diabetics thiazide-type diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or CCBs [8••]. These guidelines recommend as initial antihypertensive drug therapy in the general Black population including diabetics thiazide-type diuretics or CCBs [8••]. These guidelines recommend as initial antihypertensive drug therapy in persons with chronic kidney disease ACE inhibitors or ARBs. ACE inhibitors and ARBs should not be used together in treating hypertension [8••].

The 2013 Canadian Hypertension Education Program guidelines recommend lowering the systolic blood pressure to less than 140 mmHg in elderly persons younger than 80 years of age [10••]. These guidelines recommend lowering the systolic blood pressure to less than 150 mmHg in persons aged 80 years and older [10••]. The 2011 UK guidelines also support lowering the systolic blood pressure to less than 140 mmHg in elderly persons younger than 80 years [11••].

The 2014 ASH/International Society of Hypertension guidelines recommend lowering the blood pressure to less than 140 mmHg in elderly persons 80 years and younger [12••]. These guidelines recommend reducing the blood pressure in persons older than 80 years of age with a blood pressure of 150/90 mmHg or higher to less than 150/90 mmHg unless these persons have diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease in whom a target goal of less than 140/90 mmHg should be considered [12••].

The 2014 ASH/International Society of Hypertension guidelines provide additional detailed recommendations for elderly Black and White patients. When hypertension is the only or main condition in an elderly Black patient, the first antihypertensive drug used should be a thiazide-type diuretic or CCB. If a second antihypertensive drug is needed, an ACE inhibitor or ARB should be added. If a third antihypertensive drug is needed, a CCB plus a thiazide-type diuretic plus an ACE inhibitor or ARB should be used [12••]. When hypertension is the only or main condition in an elderly White and other non-Black patient, the first antihypertensive drug used should be a thiazide-type diuretic or CCB. If a second antihypertensive drug is needed, an ACE inhibitor or ARB should be added. If a third antihypertensive drug is needed, a CCB plus a thiazide-type diuretic plus an ACE inhibitor or ARB should be used [12••].

The ASH/International Society of Hypertension guidelines additionally indicate that in the presence of concomitant diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease, the first antihypertensive drug should be an ACE inhibitor or ARB [12••]. If a second antihypertensive drug is needed, a CCB or thiazide-type diuretic should be added. If a third antihypertensive drug is needed, a CCB plus a thiazide-type diuretic plus an ACE inhibitor or ARB should be used [12••].

The ASH/International Society of Hypertension guidelines provide additional treatment recommendations for patients with macrovascular disease. For example, when hypertension is present in elderly persons with clinical evidence of coronary artery disease, initial antihypertensive drug therapy should be a beta blocker plus an ACE inhibitor or ARB [12••]. If additional antihypertensive drug therapy is needed, a CCB or thiazide-type diuretic should be added. If additional antihypertensive drug is needed, a beta blocker plus an ACE inhibitor or ARB plus a CCB plus a thiazide-type diuretic should be used [12••]. When hypertension is present in elderly persons with a history of stroke, the first antihypertensive drug should be an ACE inhibitor or ARB [12••]. If a second antihypertensive drug is needed, a CCB or thiazide-type diuretic should be added. If a third antihypertensive drug is needed, an ACE inhibitor or ARB plus a CCB plus a thiazide-type diuretic should be used [12••]. Elderly persons with hypertension and congestive heart failure should be treated with an ACE inhibitor or ARB plus a beta blocker such as carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, or bisoprolol plus a diuretic including an aldosterone antagonist if indicated [12••].

The ABC and the Working Group on Women’s Cardiovascular Health 2014 recommendations support an systolic blood pressure goal of less than 140 mmHg in persons aged 60 years and older and less than 150 mmHg in debilitated or frail persons aged 80 years and older [13••]. The ABC states that the JNC 8 recommendations may endanger more than 36 million Americans with hypertension who are aged 60 years and older with a disproportionate negative effect on Blacks and those with chronic kidney disease and cerebrovascular disease [13••]. Similarly, the Working Group on Women’s Cardiovascular Health 2014 indicates that hypertension is the major modifiable risk factor causing coronary heart disease, heart failure, stroke, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease in women. They are concerned that the 2013 JNC 8 guidelines do not recognize that the hypertensive population is primarily women, that older women generally have poor control of hypertension, and that approximately 40 % of those with poor blood pressure control are Black women who have the highest risks for stroke, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease [13••].

Finally, the AHA/ACC/ASH 2015 guidelines on treatment of hypertension in patients with coronary artery disease state that the optimal blood pressure in patients with coronary artery disease is less than 140/90 mmHg [14••]. These guidelines recommend that patients with coronary artery disease and hypertension be treated with beta blockers plus ACE inhibitors as the drugs of first choice with the addition of CCBs or thiazide-type diuretics as needed to reduce blood pressure to less than 140/90 mmHg [14••].

Recent Studies Supporting Systolic Blood Pressure Goal Less than 140 mmHg in the Elderly

The REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study is an observational study of the incidence of stroke in persons living in the stroke belt and stroke buckle regions of the USA [15]. This study included 4181 persons aged 55–64 years, 3737 persons aged 65–74 years, and 1839 patients aged 75 years and older (mean age 79.3 years) on antihypertensive drug therapy. Median follow-up was 4.5 years for coronary heart disease or stroke and for coronary heart disease, 5.7 years for stroke, and 6.0 years for all-cause death. For persons aged 55 to 64 years, a systolic blood pressure less than 140 mmHg was associated with a lower incidence of coronary heart disease or stroke, coronary heart disease, stroke, and all-cause death, with a numerically higher incidence of cardiovascular events at systolic blood pressure levels of 140 to 149 mmHg, and especially 150 mmHg and greater [15]. The numerically lowest incidence of coronary heart disease or stroke occurred at systolic blood pressure levels of 130 to 139 mmHg [15].

For persons aged 65 to 74 years, there was a significant increase in incidence of coronary heart disease or stroke and coronary heart disease at systolic blood pressure levels of 150 mmHg and higher, for stroke at systolic blood pressure levels of 130 mmHg and higher, and for all-cause death at systolic blood pressure levels of 140 mmHg and higher [16]. For persons aged 75 years and older, there was an increase in coronary heart disease or stroke, coronary heart disease, and stroke at systolic blood pressure levels of 140 mmHg and higher and an increase in coronary heart disease or stroke, coronary heart disease, and all-cause death at systolic blood pressure levels of less than 120 mmHg [15].

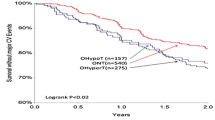

Parallel results were found after study of 8354 patients aged 60 years and older with coronary artery disease in the INternational VErapamil SR-Trandolapril (INVEST) study. Participants had a baseline systolic blood pressure of 150 mmHg and higher. After 22,308 patient years of follow-up, 57 % had a systolic blood pressure below 140 mmHg, 21 % had a systolic blood pressure of 140 to 149 mmHg, and 22 % had a systolic blood pressure of 150 mmHg and higher [16]. The primary outcome of all-cause death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke occurred in 9.36 % of patients with a systolic blood pressure less than 140 mmHg, in 12.71 % of patients with a systolic blood pressure of 140–149 mmHg, and in 21.3 % of patients with a systolic blood pressure of 150 mmHg and higher (p < 0.0001) on follow-up [16]. Using propensity score analyses, compared with a systolic blood pressure of less than 140 mmHg, a systolic blood pressure of 140 to 149 mmHg increased cardiovascular mortality by 34 % (p = 0.04), total stroke by 89 % (p = 0.002), and nonfatal stroke by 70 % (p = 0.03) [17]. Compared with a systolic blood pressure of less than 140 mmHg, a systolic blood pressure of 150 mmHg and higher increased the primary outcome by 82 % (p < 0.0001), all-cause mortality by 60 % (p < 0.0001), cardiovascular mortality by 218 % (p < 0.0001), and total stroke by 283 % (p < 0.0001) [17].

Optimal Versus Excessive Control of Hypertension in the Elderly

It is well established that hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease in the elderly [1••]. Hypertension is present in 69 % of persons who have a first myocardial infarction [17], in 77 % of persons who have a first stroke [17], in 74 % of persons who have congestive heart failure [17], and in 60 % of elderly patients who have peripheral arterial disease [18]. Hypertension is also a major risk factor in elderly persons for dissecting aortic aneurysm, sudden death, angina pectoris, chronic kidney disease, left ventricular hypertrophy, thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, the metabolic syndrome, vascular dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and ophthalmologic disorders [1••].

Yet hypertension is commonly under-treated in the elderly [1••]. Blood pressure is adequately controlled in only 28 % of women and in 36 % of men aged 60 to 79 years and in only 23 % of women and 38 % of men aged 80 years and older [19]. These numbers would increase substantially if the JNC 8 panel recommendations are widely adopted. Were this to happen, 6 million adults in the USA aged 60 years and older would be ineligible for treatment with antihypertensive drugs, and treatment intensity would be decreased for an additional 13.5 million older persons [20], leading to increased incidences of coronary events, stroke, heart failure, cardiovascular mortality, and other adverse events associated with inadequate blood pressure.

However, the systolic blood pressure should not be lowered by antihypertensive drug therapy to a level less than 130 mmHg in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events as was recommended by the 2007 AHA guidelines [21]. These guidelines recommended that patients with acute myocardial infarction, unstable angina pectoris or stable ischemic heart disease [1••, 14••, 22, 23], diabetes mellitus [24–27], chronic kidney disease [28–31], and ischemic stroke [32] have a target systolic blood pressure less than 130 mmHg. These guidelines also recommended on the basis of expert medical opinion that blood pressure should be reduced to less than 120/80 mmHg in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction [21]. In contrast with these recommendations, an analysis of the effect of baseline systolic blood pressure on clinical outcomes among 7785 patients with mild to moderate chronic heart failure in the Digitalis Investigation Group trial [33] showed harm with systolic blood pressure reduction beyond 120 mmHg. Compared with a baseline systolic blood pressure of higher than 120 mmHg, a baseline systolic blood pressure of 120 mmHg or lower was associated during 5 years of follow-up with a 15 % increase in cardiovascular mortality (p = 0.032), a 30 % increase in heart failure mortality (p = 0.006), a 13 % increase in cardiovascular hospitalization (p = 0.008), a 10 % increase in all-cause hospitalization (p = 0.017), and a 21 % increase in heart failure hospitalization (p = 0.002) [33].

All elderly persons being treated for hypertension should in addition have their blood pressure measured after standing for 1 to 3 min to evaluate for postural hypotension [1••]. Orthostatic hypotension is defined as a reduction in systolic blood pressure of 20 mmHg or more or in diastolic blood pressure of 10 mmHg or more within 3 min of standing and can result from blunting of the carotid baroreflex due to increased stiffness of the carotid arteries [1••]. Orthostatic hypotension may result in falls, syncope, and fractures.

Renal Artery Stenosis

The most common cause of secondary hypertension in elderly persons is renal artery stenosis [34]. Although uncontrolled studies have suggested that renal artery angioplasty or stenting in patients with renal artery stenosis with hypertension reduce systolic blood pressure and stabilize chronic kidney disease, randomized, controlled trials of renal artery angioplasty have not shown that this procedure is efficacious in reducing blood pressure [35–37].

The Angioplasty and Stent for Renal Artery Lesions (ASTRAL) trial randomized 806 patients with atherosclerotic renovascular disease to renal artery revascularization plus medical treatment or to medical treatment only [35]. At 34-month median follow-up, compared with medical treatment only, the renal artery revascularization group had a similar systolic blood pressure, a smaller decrease in diastolic blood pressure, and similar rates of renal events [35]. Serious complications associated with revascularization also developed in 23 revascularized patients, including two deaths and three amputations of toes or limbs [35].

A second trial randomized 140 patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and a creatinine clearance below 80 ml/min/1.73 m2 to stent placement plus medical treatment or medical treatment alone. Of 64 patients randomized to stent placement, 46 underwent the procedure [36]. Stent placement did not affect progression of impaired renal function. The stent group also had two procedure-related deaths, one late death due to an infected hematoma, and one patient who needed dialysis because of cholesterol embolism [36].

The Cardiovascular Outcomes in Renal Atherosclerotic Lesions (CORAL) study randomized 947 patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and either systolic hypertension on two or more antihypertensive drugs or chronic kidney disease to medical therapy plus renal artery stenting or to medical therapy only [37]. At 43-month median follow-up, the primary composite endpoint of mortality from cardiovascular or renal causes, myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure hospitalization, progressive renal insufficiency, or need for renal replacement therapy was similar in both groups [37]. The incidence of the individual components of the primary endpoint and of all-cause mortality was similar in both groups. However, the stent group had a 2.3 mmHg lower systolic blood pressure than the medical treatment only group (p = 0.03) [37].

These studies demonstrate that for most patients with renal artery stenosis and either hypertension or chronic kidney disease, management of renal artery stenosis should be limited to medical treatment only [38]. Whether patients with severe stenosis to a single functioning kidney, severe stenosis and acute kidney injury, or flash pulmonary edema might benefit from renal artery stenting needs to be investigated [38].

Resistant Hypertension

An AHA statement has defined resistant hypertension as a blood pressure remaining above goal despite the use of three optimally dosed antihypertensive drugs from different classes, with one of the three drugs being a diuretic [39]. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guideline states that these three drugs should be an ACE inhibitor or ARB plus a CCB plus a thiazide-type diuretic [40]. A normal home blood pressure or 24-h ambulatory blood pressure excludes resistant hypertension [40, 41]. Poor patient compliance, inadequate doses of antihypertensive medications, inadequate choice of combinations of antihypertensive drugs, poor office blood pressure measurement technique, and having to pay for drugs out of pocket may contribute to pseudo-resistant hypertension [1••, 40, 42]. Factors contributing to true resistant hypertension include excess sodium dietary intake, excess alcohol intake, obesity, use of cocaine, amphetamines, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, contraceptive hormones, adrenal steroid hormones, sympathomimetic drugs (nasal decongestants and diet pills), erythropoietin, licorice, ephedra, progressive renal insufficiency, inadequate diuretic therapy, and secondary causes of resistant hypertension [1••, 34, 40]. Some data support using spironolactone as a fourth drug to treat resistant hypertension if the serum potassium level is 4.5 mmol/L or lower [40, 43], though this must be done with caution in older adults with chronic kidney disease. New drugs and device therapy are currently being investigated as treatment for resistant hypertension [44].

Renal Sympathetic Denervation

Early inadequately controlled studies found that renal sympathetic denervation was very effective in reducing blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension [45–47]. An international expert consensus statement recommended consideration of renal sympathetic denervation only in patients whose blood pressure could not be controlled by lifestyle modification plus drug therapy tailored to current guidelines [48].

However, excitement for this technology diminished with publication of the Symplicity HTN-3 study, a prospective, single-blind randomized, sham-controlled study which randomized 535 patients with resistant hypertension in a 2:1 ratio to renal sympathetic denervation or a sham procedure [49]. The primary efficacy endpoint of change in office systolic blood pressure at 6 months was a decrease of 14.13 mmHg for renal sympathetic denervation versus 11.74 mmHg for the sham procedure (p not significant) [49]. The secondary efficacy endpoint of change in mean 24-h ambulatory systolic blood pressure at 6 months was a decrease of 6.75 mmHg for renal sympathetic denervation versus 4.79 mmHg for the sham procedure (p not significant) [49]. This study did not show at 6-month follow-up any benefit for renal sympathetic denervation in reducing ambulatory blood pressure during the day, night, or 24-h periods compared with the sham procedure [50].

Frail Elderly Persons

Randomized clinical trial studies on treatment of hypertension in frail elderly persons have not been performed [51]. The Predictive Values of Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness in Institutionalized Very Aged Population (PARTAGE) study was a longitudinal observational study performed in 1130 frail persons aged 80 years and older (mean age 88 years) living in nursing homes in Italy and France [52]. This study found a 78 % increase in mortality in frail elderly persons with a systolic blood pressure below 130 mmHg receiving two or more antihypertensive drugs (32.2 %) compared with frail elderly persons with a systolic blood pressure below 130 mmHg treated with 0–1 antihypertensive drug (19.7 %) (p < 0.001) [52]. Three sensitivity analyses confirmed the significant excess mortality in these persons with a systolic blood pressure below 130 mmHg who were taking two or more antihypertensive drugs by (1) propensity score-matched subsets, (2) adjustment for cardiovascular morbidities, and (3) exclusion of persons treated with antihypertensive drugs who did not have a history of hypertension. Consistent with this finding, randomized clinical antihypertensive drug studies have shown a J-shaped relationship between blood pressure and all-cause death, fatal and nonfatal stroke, and congestive heart failure in populations at low and high risk for cardiovascular events [53].

It is very surprising that in these frail very elderly patients with a systolic blood pressure lower than 130 mmHg who were receiving two or more antihypertensive drugs (20 % of the studied group), multiple antihypertensive drugs were continued [52]. There are few studies to support this approach, as both overtreatment of hypertension as well as inadequate control of hypertension may cause adverse clinical outcomes in frail elderly persons [51]. Until adequate clinical trial data are available for treatment of hypertension in frail elderly persons, it is suggested that the ACC/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly [1••] and the other recent hypertension guidelines [7••, 9••, 10••, 11••, 12••, 13••, 14••] with the exception of JNC 8 [8••] be followed.

Conclusions

On the basis of the available data including both clinical trials and observational studies, management of hypertension in the elderly should adhere to the ACC/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly which recommends that the systolic blood pressure be lowered to below 140 mmHg in persons aged 60 to 79 years and to 140 to 145 mmHg if tolerated in persons aged 80 years and older [1••]. However, it should be emphasized that randomized clinical trial data are not available on treatment of hypertension in frail elderly persons [51]. In addition, as randomized clinical antihypertensive drug studies have shown a J-shaped relationship between both systolic and diastolic blood pressure and all-cause death, fatal and nonfatal stroke, and congestive heart failure in populations at low and high risk for cardiovascular events [53], treatment should not aim to achieve systolic blood pressure targets approaching 120 mmHg in older patients.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •• Of major importance

Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, Artinian NT, Bakris G, Brown AS, et al. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus documents developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology, Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2037–114. These guidelines recommend that the systolic blood pressure be lowered to less than 140 mmHg in persons aged 60–79 years and to 140 to 145 mmHg if tolerated in persons aged 80 years and older.

SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA. 1991;265:3255–64.

Perry Jr HM, Davis BR, Price TR, Applegate WB, Fields WS, Guralnik JM, et al. Effect of treating isolated systolic hypertension on the risk of developing various types and subtypes of stroke. The Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA. 2000;284:465–71.

Kostis JB, Davis BR, Cutler J, Grimm Jr RH, Berge KG, Cohen JD, et al. Prevention of heart failure by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. JAMA. 1997;278:212–6.

Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Eng J Med. 2008;358:1887–98.

Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1665. doi:10.1136/bmj.b1665.

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Bohm M, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2159–219. These hypertension guidelines recommend lowering the systolic blood pressure to less than 140 mmHg in persons aged 60 to 79 years and in persons aged 80 years and older with a systolic blood pressure of 160 mmHg or higher to between 140–150 mmHg provided they are in good physical and mental conditions.

James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507–20. These guidelines recommend lowering the systolic blood pressure in persons aged 60 years or older to less than 150 mmHg if they do not have diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease and to less than 140 mmHg if they have diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease.

Wright Jr JT, Fine LJ, Lackland DT, Ogedegbe G, Dennison-Himmelfarb C. Evidence supporting a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 150 mmHg in patients aged 60 years or older: the minority view. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:499–503. This minority report from JNC 8 recommends that the systolic blood pressure goal in persons aged 60 to 79 years with hypertension without diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease should be lowered to less than 140 mmHg.

Hackam DG, Quinn RR, Ravani P, Rabi DM, Dasgupta K, Daskalopoulou SS, et al. The 2013 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:528–42. These guidelines recommend lowering the systolic blood pressure to less than 140 mmHg in elderly persons younger than 80 years of age and to less than 150 mmHg in persons aged 80 years and older.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Hypertension: clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2011. These guidelines recommend lowering the systolic blood pressure to less than 140 mmHg in elderly persons younger than 80 years.

Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, Mann S, Lindholm LH, Kenerson JG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community. A statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2014;16:14–26. These guidelines recommend lowering the blood pressure to less than 140/90 mmHg in persons aged 80 years and younger and to less than 150/90 mmHg in persons older than 80 years unless these persons have diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease when a target goal of less than 140/90 mmHg should be considered.

Krakoff LR, Gillespie RL, Ferdinand KC, Fergus IV, Akinboboye O, Williams KA, et al. 2014 hypertension recommendations from the Eighth Joint National Committee panel members raise concerns for elderly black and female populations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:394–402. The Association of Black Cardiologists and the Working Group on Women’s Cardiovascular Health also support a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 140 mmHg in persons aged 60 to 79 years and of less than 150 mmHg in persons aged 80 years and older.

Rosendorff C, Lackland DT, Allison M, Aronow WS, Black HR, Blumenthal RS, et al. AHA/ACC/ASH scientific statement. Treatment of hypertension in patients with coronary artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Society of Hypertension. Circulation 2015; first published on March 31, 2015 as doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000207. These guidelines state that the optimal blood pressure in patients with coronary artery disease is less than 140/90 mmHg.

Banach M, Bromfield S, Howard G, Howard VJ, Zanchetti A, Aronow WS, et al. Association of systolic blood pressure levels with cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality among older adults taking antihypertensive medication. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176:219–26.

Bangalore S, Gong Y, Cooper-DeHoff RM, Pepine CJ, Messerli FH. 2014 Eighth Joint National Committee panel recommendation for blood pressure targets revisited: results from the INVEST study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:784–93.

Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:e21–181.

Aronow WS, Ahmed MI, Ekundayo OJ, Allman RM, Ahmed A. A propensity-matched study of the association of PAD with cardiovascular outcomes in community-dwelling older adults. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:130–5.

Lloyd-Jones DM, Evans JC, Levy D. Hypertension in adults across the age spectrum: current outcomes and control in the community. JAMA. 2005;294:466–72.

Navar-Boggan AM, Pencina MJ, Williams K, Sniderman AD, Peterson ED. Proportion of US adults potentially affected by the 2014 hypertension guideline. JAMA. 2014;311:1424–9.

Rosendorff C, Black HR, Cannon CP, Gersh BJ, Gore J, Izzo Jr JL, et al. Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2007;115:2761–88.

Aronow WS. Hypertension guidelines. Hypertension. 2011;58:347–8.

Bangalore S, Qin J, Sloan S, Murphy SA, Cannon CP. What is the optimal blood pressure in patients after acute coronary syndromes? Relationship of blood pressure and cardiovascular events in the PRavastatin Or atorVastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (PROVE IT-TIMI) 22 trial. Circulation. 2010;122:2142–51.

Cooper-DeHoff RM, Gong Y, Handberg EM, Bavry AA, Denardo SJ, Bakris GL, et al. Tight blood pressure control and cardiovascular outcomes among hypertensive patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease. JAMA. 2010;304:61–8.

ACCORD Study Group, Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, Goff Jr DC, Grimm Jr RH, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575–85.

Mancia G, Schumacher H, Redon J, Verdecchia P, Schmieder R, Jennings G, et al. Blood pressure targets recommended by guidelines and incidence of cardiovascular and renal events in the ONgoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET). Circulation. 2011;124:1727–36.

Redon J, Mancia G, Sleight P, Schumacher H, Gao P, Pogue J, et al. Safety and efficacy of low blood pressures among patients with diabetes: subgroup analyses from the ONTARGET (ONgoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:74–83.

Upadhyay A, Earley A, Haynes SM, Uhlig K. Systematic review: blood pressure target in chronic kidney disease and proteinuria as an effect modifier. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:541–8.

Appel LJ, Wright Jr JT, Greene T, Agodoa LY, Astor BC, Bakris GL, et al. Intensive blood-pressure control in hypertensive chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:918–29.

Lazarus JM, Bourgoignie JJ, Buckalew VM, Greene T, Levey AS, Milas NC, et al. Achievement and safety of a low blood pressure goal in chronic renal disease: the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Hypertension. 1997;29:641–50.

Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Loriga G, Ganeva M, Ene-lordache B, Turturro M, et al. Blood-pressure control for renoprotection in patients with non-diabetic chronic renal disease (REIN-2): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:939–46.

Ovbiagele B, Diener HC, Yusuf S, Martin RH, Cotton D, Vinisko R, et al. Level of systolic blood pressure within the normal range and risk of recurrent stroke. JAMA. 2011;306:2137–44.

Banach M, Bhatia V, Feller MA, Mujib M, Desai RV, Ahmed MI, et al. Relation of baseline systolic blood pressure and long-term outcomes in ambulatory patients with chronic mild to moderate heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1208–14.

Chiong JR, Aronow WS, Khan IA, Nair CK, Vijavaraghavan K, Dart RA, et al. Secondary hypertension: current diagnosis and treatment. Int J Cardiol. 2008;124:6–21.

ASTRAL Investigators, Wheatley K, Ives N, Gray R, Kalra PA, Moss JG, et al. Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1953–62.

Bax L, Woittiez AJ, Kouwenberg HJ, Mali WP, Buskens E, Beek FJ, et al. Stent placement in patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and impaired renal function: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:840–8.

Cooper CJ, Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, Jamerson K, Henrich W, Reid DM, et al. Stenting and medical therapy for atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:13–22.

Banach M, Serban C, Aronow WS, Rysz J, Dragan S, Lerma EV, et al. Lipid, blood pressure and kidney update 2013. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014;46:947–61.

Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S, Goff DC, Murphy TP, Toto RD, et al. Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2008;117:e510–26.

Myat A, Redwood SR, Quereshi AC, Spertus JA, Williams B. Resistant hypertension. BMJ. 2012;345, e7473. doi:10.1136/bmj.e7473 (published 20 November 2012).

Pimenta E, Calhoun DA. Resistant hypertension. Incidence, prevalence, and prognosis. Circulation. 2012;125:1594–6.

Gandelman G, Aronow WS, Varma R. Prevalence of adequate blood pressure control in self-pay or Medicare patients versus Medicaid or private insurance patients with systemic hypertension followed in a university cardiology or general medicine clinic. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:815–6.

Chapman N, Dobson J, Wilson S, Dahlof B, Sever PS, Wedel H, et al. Effect of spironolactone on blood pressure in subjects with resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:839–45.

Laurent S, Schlaich M, Esler M. New drugs, procedures, and devices for hypertension. Lancet. 2012;380:591–600.

Symplicity HTN-1 Investigators. Catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation for resistant hypertension: durability of blood pressure reduction out to 24 months. Hypertension. 2011;57:911–7.

Esler MD, Krum H, Schlaich M, Schmieder RE, Bohm M, Sobotka PA, et al. Renal sympathetic denervation for treatment of drug-resistant hypertension: one-year results from the Symplicity HTN-2 randomized, controlled trial. Circulation. 2012;126:2976–82.

Davis MI, Filion KB, Zhang D, Eisenberg MJ, Afilalo J, Schiffrin EL, et al. Effectiveness of renal denervation therapy for resistant hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:231–41.

Schlaich MP, Schmieder RE, Bakris G, Blankestijn PJ, Bohm M, Campese VM, et al. International expert consensus statement: percutaneous transluminal renal denervation for the treatment of resistant hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:2031–45.

Bhatt DL, Kandzari DE, O’Neill WW, D’Agostino R, Flack JM, Katzen BT, et al. A controlled trial of renal denervation for resistant hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:393–401.

Bakris GL, Townsend RR, Liu M, Cohen SA, D’Agostino R, Flack JM, et al. Impact of renal denervation on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure: results from SYMPLICITY HTN-3. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1071–8.

Aronow WS. Multiple blood pressure medications and mortality among elderly individuals. JAMA. 2015;313:1362–3.

Benetos A, Labat C, Rossignol P, Fay R, Rolland Y, Valbusa F, et al. Treatment with multiple blood pressure medications, achieved blood pressure, and mortality in older nursing home residents: the PARTAGE study. JAMA Intern Med. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed. 2014.8012.

Banach M, Aronow WS. Blood pressure J curve. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2012;14:556–66.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Elderly + Heart Disease

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aronow, W.S. Management of Hypertension in the Elderly. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 9, 41 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12170-015-0469-y

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12170-015-0469-y