Abstract

Hypertension is the most powerful risk factor for cardiovascular disease and mortality globally, especially in the elderly population. In view of aging populations and the high prevalence of hypertension among the elderly, the benefits of lowering blood pressure in the United States and other societies include decreased fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events and total mortality. Evidence-based guidelines have supported practitioners in carefully treating this special population. Nevertheless, the guidelines have provided inconsistent recommendations regarding target blood pressure in the elderly. There is a delicate balance between both the benefits (including preserving autonomy and quality of life) and the harms of antihypertensive therapy that should be considered when treating the elderly population. This chapter highlights past and recent trials among elderly hypertensive patients and summarizes major current and emerging guideline considerations in the elderly population. First step agents include diuretics and calcium channel blockers with additional agents as needed (depending upon compelling indications), to lower blood pressure and decrease cardiovascular outcomes.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Approximately 85.7 million American adults have hypertension, and the age-adjusted prevalence among United States (U.S.) adults ≥20 years of age is estimated to be 34.0% in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2014 [1]. In 2011–2014, the prevalence of hypertension was 11.6% among those 20–39 years of age, 37.3% among those 40–59 years of age, and 67.2% among those ≥ 60 years of age [1]. During the same timeframe, the prevalence of hypertension was 67.2% among U.S. adults ≥ 60 years of age and only 54.0% had controlled blood pressure (BP). According to NHANES 2005–2010, 76.5% of U.S. adults ≥ 80 years of age had hypertension, representing an increase from 69.2% in 1988–1994 [2]. In elderly Americans, hypertension is the most important risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), with estimates that 69% of patients with an incident myocardial infarction, 77% with incident stroke, and 74% with incident heart failure have antecedent hypertension [3]. Moreover, hypertension is a major risk factor for incident diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, and chronic kidney disease ([3]).

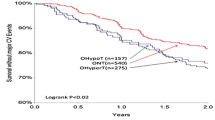

The prevalence of hypertension continues to rise in the U.S. with population growth, population aging, and persistent adverse behavioral risk factors, including high sodium and low potassium dietary patterns, physical inactivity, and increasing obesity. With advancing age, there is a gender transition from the younger (< 45 years) where hypertension affects more men than women, to the older population (> 65 years) where hypertension affects more women than men [4] (Fig. 6.1). In addition to more prevalent hypertension in older women than men, BP control is more difficult to achieve in women than men [3]. Among patients 80 years of age with hypertension, only 23% of women (versus 38% of men) had BP < 140/90 mm Hg ([5]). Furthermore, older adults visiting their physicians for antihypertensive pharmacotherapy versus younger adults were significantly more likely to include three or more hypertensive medications. A total of 62% of all visits included the provision, prescription, or continuation of one or more hypertensive medications. In 2013, 82% of visits to office-based physicians by adults with hypertension were made by those who had additional chronic conditions [6].

Prevalence of hypertension among adults aged 18 and over, by sex and age: United States, 2011–2014 1Crude estimates are 31.3% for total, 31.0% for men, and 31.5% for women. 2Significant difference from age group 18–39. 3Significant difference from age group 40–59. 4Significant difference from women for same age group. 5Significant linear trend. NOTE: Estimates for the 18 and over category were age-adjusted by the direct method to the 2000 U.S. census population using age groups 18–39, 40–59, and 60 and over. (Source: CDC/NCHS, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2014. Yoon et al. [45])

Evidence-based guidelines provide inconsistent recommendations regarding the optimal systolic blood pressure (SBP) treatment targets in the elderly populations. Historically, in the period before the landmark Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) trial in 1991, elevated BP in this population (specifically systolic hypertension alone) had been somewhat controversial. Indeed, prior to landmark trials, hypertension was considered to be a normal compensatory phenomenon. For example in 1937, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had a BP reading of 162/98 mm Hg at the age of 54 did not receive treatment to reduce his BP from his personal physician, as this was consistent with medical knowledge and opinion at that time [7]. Subsequently, significant cardiovascular benefits were demonstrated in the elderly in multiple studies.

Pathophysiologic Considerations in Elderly Patients

Specific considerations must be taken into account when treating hypertension in the elderly population. Blood pressure represents the confluence of cardiac and vascular properties such as arterial stiffness, endothelial dysfunction, increased cardiac output, high peripheral vascular resistance and extracellular/intravascular volume. Blood pressure is a function of blood flow and vascular resistance. In clinical practice, pressure refers to a pulsatile phenomenon defined in terms of SBP and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), representing the extremes of the BP oscillation around a mean BP value. These are quantitative measures of BP; however, BP and flow fluctuate during the cardiac cycle [3]. Systolic blood pressure increases with age until the eighth or ninth decade of life, in contrast to DBP, which rises only until middle age and then either levels off or slightly decreases.

As blood vessels become stiff due to age-related processes, and/or other co-morbidities, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and peripheral vascular diseases, SBP rises. The wider the pulse pressure, the smaller the ratio of DBP to SBP lowering with antihypertensive therapy, which is consistent with well-known hemodynamic principles. Indeed, DBP rises with increased peripheral arterial resistance but falls with increased stiffness of the large conduit arteries. Therefore, antihypertensive therapy will maximize the decrease in SBP and minimize the reduction in DBP in direct proportion to the age-related stiffening of large arteries [8].

Notably, elderly patients are prone to having isolated systolic hypertension (ISH)—SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg; DBP < 90 mm Hg. Isolated systolic hypertension is characterized by reduced vascular compliance, often combined with increased peripheral resistance and is a result of increased arterial stiffness from arteriosclerosis or impairment of nitric oxide–mediated vasodilation [9, 10]. The prevalence of ISH is very significant in elderly patients with hypertension demonstrated in more than 65% of hypertensive patients aged ≥ 60 years and more than 90% of those aged > 70 years [11].

Additionally, salt sensitivity is more frequently observed in older than in younger subjects [12] resulting in a higher SBP and higher pulse pressure when more salt is consumed by elderly individuals. Finally, elderly persons are at increased risk for orthostatic hypotension, which is present in up to 20 percent of patients older than 65 years [13] and can lead to increased risk for syncope, falls, and injuries.

Appropriate Determination of the Diagnosis of Hypertension

According to a recent Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Consumer Update, BP evaluations should be done in a clinic or a medical office, by using BP cuffs of various sizes to ensure the reading is accurate. There is no such thing as a “standard” cuff to fit a “standard” arm, thus the BP kiosks at various drug stores, pharmacies, or grocery stores may be inaccurate [14]. The most common error in BP measurement is use of an improperly sized cuff. The bladder length recommended by the American Heart Association is 80% of the patient’s arm circumference, and the ideal width is at least 40% [15].

The Million Hearts Campaign is a national initiative of the Department of Health and Human Services whose goal is to prevent one million heart attacks and strokes by 2017 [16]. This collaborative effort involves multiple government agencies and nongovernmental collaborators. The initiative is co-led by the Centers for Disease Control and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services within the Department of Health and Human Services. One of the Million Hearts main areas of focus is improving medication adherence through knowledge dissemination, stakeholder activation, creation of incentives, measuring and reporting, improving population health, and research. The Million Hearts Campaign supports self-monitoring BP particularly in certain types of patients, including the elderly, people with diabetes or chronic kidney disease, pregnant women, and those with suspected or confirmed white coat hypertension [17]. Clinicians should encourage patients to take any home BP monitor they use to their provider’s office to measure its accuracy against a comparable device before the readings are accepted. The Canadian Hypertension Education Program Guidelines developed a technique for assessing automated office blood pressure (AOBP) to ensure accuracy (Table 6.1).

For the elderly population, multiple BP readings should be done prior to diagnosing hypertension. Once hypertension is diagnosed, prescription initiation and intensification should proceed as, start low and go slow, and routinely monitor both seated and standing BP as orthostatic hypotension is more prevalent in the elderly population. If the patient has significant orthostasis, then the standing BP should take precedence.

Evolution of Clinical Trial Evidence

Based mainly on observational data, controversy lies in the J-shaped relation (J-curve) between the risk of myocardial infarction and treated BP which led to the suggestion that a reduction of pressure induced by drugs might cause and prevent myocardial ischemia [19], especially in the elderly population. Theoretically speaking, there is likely a turning point of BP below which the risk of cardiovascular events increases, as BP is essential for the perfusion of all organs. Overall, there have been conflicting views on the treatment of hypertension in very old patients as some studies suggested that BP and death were inversely related. Presently, the J-curve issue remains unresolved, however several randomized studies have attempted to address this controversy. Given that the J-curve demonstrated a link between DBP and coronary events, McEvoy and colleagues studied 11,565 adults in an observational trial from the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) cohort, to evaluate the independent association of DBP with myocardial damage and with coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, or death over 21 years. There was a trend toward higher risk of progression of subclinical myocardial damage and incident CHD among those with DBP < 60 and SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg [20]. Thus, suggesting that low DBP levels, particularly < 60 mm Hg, might harm the myocardium and are associated with subsequent CHD. However, this phenomenon appears to be most likely in clinical settings where SBP is ≥ 120 mm Hg and pulse pressure is higher.

Published in 1989, the European Working Party on High Blood Pressure in the Elderly (EWPHE) trial comprised 840 men and women over 60 years old, with a SBP in the range of 160–239 mm Hg and a diastolic pressure in the range 90–119 mm Hg, who were randomized to receive active treatment (hydrochlorothiazide with triamterene) or matching placebo. A significant BP difference of 20/8 mm Hg was obtained between the groups and maintained during 5 years of follow-up. The EWPHE trial demonstrated that active treatment was associated with a 27% reduction in cardiovascular mortality (p = 0.037), a 60% reduction in fatal myocardial infarctions (p = 0.043), a 52% reduction in strokes (p = 0.026), and a significant reduction in the incidence of severe congestive heart failure [21]. In a follow-up paper, Staessen and colleagues evaluated mortality and other possible correlates of mortality in the EWPHE patients, who were grouped in thirds of the distribution of treated blood pressure. The EWPHE trial demonstrated a U-shaped relation with treated systolic pressure and an inverse association with treated diastolic pressure. The U curve between mortality and diastolic pressure in patients taking placebo indicates that the increased mortality in the lower thirds of the actively treated patients may not be drug induced; however, it could be secondary to deterioration in general health, as suggested by the decreases in body weight and hemoglobin concentration ([22]).

The Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension (STOP-Hypertension) was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind study of 1,627 patients (mean age 76; mean BP 195/102 mm Hg) on antihypertensive treatment (atenolol, hydrochlorothiazide plus amiloride, metoprolol, or pindolol) compared to placebo.At study completion, the average BP reduction was 20/8 mm Hg in the actively treated group compared to placebo. The mean follow-up was 2.5 years [23].Compared with placebo, active treatment significantly reduced the number of primary endpoints (94 vs 58; p = 0.0031) and stroke morbidity and mortality (53 vs 29; p = 0.0081), as well as a significantly reduced number of deaths in the active treatment group (63 vs 36; p = 0.0079). These benefits were noticeable up to age 84 years, and STOP-Hypertension concluded that the elderly aged 70–84 conferred significant and clinically relevant reductions in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality as well as in total mortality in both men and women.

In 1991, the SHEP trial was the first randomized controlled trial to demonstrate the benefits of treating ISH in those with an average age of 72 years and an average SBP at entry of 170 with a mean diastolic of 77 mm Hg, randomized to either diuretic therapy (chlorthalidone plus atenolol or reserpine, if needed) or placebo. Out of 4,736 total and after an average of 4.5 years, the average BP at study end was 155/72 and 143/65 mm Hg, control and actively treated, respectively. The SHEP trial revealed a 37% reduction in nonfatal strokes, 32% decrease in cardiovascular events, 33% decrease in nonfatal myocardial infarctions, and a 55% reduction in heart failure in the treated versus placebo group ([24]). In support of the SHEP trial, the Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults demonstrated that active treatment led to a significant reduction in cardiovascular events in men and women aged 65–74 with sustained mild to moderate hypertension [25]. Additionally, the Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) revealed benefits of antihypertensive treatment (nitrendipine with enalapril and hydrochlorothiazide, if needed) that were similar to those trials in older patients with combined systolic and diastolic hypertension [26].

By 2008, nevertheless, there still was no solid evidence that antihypertensive drug treatment in the very elderly (≥ 80 years) was either safe or effective. Thus, the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) was the first randomized trial to demonstrate benefits of treating hypertension in 3,845 very elderly from Australia, China, Europe, and Tunisia [27]. Overall, the results demonstrated clear benefits in those patients 80 years or older whose SBP was > 160 mm Hg with active treatment (indapamide with or without perindopril) as compared to placebo. The BP in the active treatment group was 15/6.1 mm Hg lower than the placebo group, revealing a 30% reduction in the rate of fatal and non-fatal stroke (95% CI −1–51, p = 0.06), 39% reduction in rate of death from stroke (95% CI 1–62, p = 0.05), 21% reduction in rate of death from any causes (95% CI 4–35, p = 0.02), 23% reduction in the rate of death from cardiovascular causes (95% CI −1–40, p = 0.06), and a 64% reduction in the rate of heart failure (95% CI 42–78, p < 0.001).

Accordingly, Cardio-Sis (CARDIO vascolari del Controllodella Pressione Arteriosa SI Stolica) trial of 1,111 participants without diabetes with a mean age of 67 years compared a SBP of ≤ 130 mm Hg to the standard < 140 mm Hg SBP (open label therapywith combinations of furosemide, ramipril, telmisartan, amlodipine, bisoprolol, and transdermal clonidine; combinations of ramipril and of telmisartan with hydrochlorothiazide were also available). The primary (electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy)and secondary end points (composite of cardiovascular events) 2 years post-randomization, were less frequent in the tightthan in the standard control group in patients with and without established CVD at initiation. Therefore, the advantage of a “tightly controlled group” as compared to a standard control group had a significantly lower incidence of new left ventricular hypertrophy, atrial fibrillation, and need for coronary revascularization [28], without any paradoxical rise in the risk of events at low levels of achieved BP during follow-up.

Recent Guidelines Endorsing Higher Systolic BP Goals in Elderly

A 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high BP in adults consisted of a report from the members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee Panel (JNC-8P). This nomenclature accurately reflects the Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA) publication from the JNC-8P and avoids the perception that the federal government and any of the 39 professional organizations that reviewed and endorsed the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC-7) were responsible for conclusions. The JNC-8P members based their recommendations upon strict adherence of evidence-based medicine, consensus, and expert opinion, and their extensive review process recommended for those ≥ 60 years of age, a SBP ≥ 150 mm Hg threshold for initiating antihypertensive drug treatment and a treatment goal SBP of < 150 mm Hg [29].

The persistent controversy lies in the generalized recommendation for the higher threshold in the elderly hypertensive patients, as the higher SBP threshold is especially threatening to African Americans and women who are disproportionately affected with hypertension in this age demographic [30]. Furthermore, as most Americans ≥ 60 years of age with hypertension are women, women will be differentially affected by the recommendation to raise the SBP threshold for initiating treatment (to 150 mm Hg) and to raise the treatment target (<150 mm Hg) for people ≥ 60 years of age. Unfortunately, the JNC-8P 2014 recommendations offer no recognition that the elderly hypertensive population is primarily female, that older women generally have poorly controlled hypertension, and that approximately 40% of those with poor BP control are African American women, who have the highest risks for stroke, heart failure, and chronic renal disease.

In addition, according to new evidence-based guidelines jointly developed by the American College of Physicians (ACP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) in 2017, they collaboratively recommend that physicians initiate treatment in adults aged 60 years old and older with persistent SBP at or above 150 mm Hg to achieve a target SBP of less than 150 mm Hg in order to reduce the risk of mortality, stroke, and cardiac events (Grade: strong recommendation, high-quality evidence). The second recommendation is that clinicians consider initiating or intensifying pharmacologic treatment in adults aged 60 years or older with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack to achieve a target SBP of less than 140 mm Hg to reduce the risk for recurrent stroke (Grade: weak recommendation, moderate-quality evidence). The final recommendation is that clinicians should consider initiating or intensifying pharmacologic treatment in some adults aged 60 years or older at high cardiovascular risk, based on individualized assessment, to achieve a target SBP of less than 140 mm Hg to reduce the risk for stroke or cardiac events (Grade: weak recommendation, low-quality evidence). These clinical recommendations regarding the benefits and harms of higher versus lower BP targets for hypertension in adults 60 years and older were developed for utilization by all clinicians caring for adults 60 years and older with hypertension [31]. Adapted from the Million Hearts® website, Table 6.2 provides practical approaches to effective provider-patient communication to control hypertensive patients.

Given that the JNC-8P recommendations were challenged by several in the cardiology community over the elevated hypertension treatment threshold, and in recognition of significant new clinical trial evidence in hypertension, the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/American Academy of Physician Assistants/Association of Black Cardiologists/American College of Preventative Medicine/American Geriatrics Society/American Pharmacists Association/American Society of Hypertension/American Society for Preventative Cardiology/National Medical Association/Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults is currently in development and will serve as an update to the 2003 JNC-7 that was the final hypertension guideline headed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). The 2003 JNC-7 was the final and most recent hypertension management guideline to be endorsed by the ACC/AHA, however the JNC-8P was not endorsed by these organizations.

Impact OF SPRINT and Future Guidelines for Blood Pressure Control in Elderly

According to the landmark clinical trial sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) was a randomized trial of 9,361 community-dwelling adults (mean age 68 years) that evaluated whether lowering SBP to a target < 120 versus < 140 mm Hg reduced major cardiovascular (CV) events (i.e., myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, acute heart failure and CV mortality) [32]. Of the 9,361 participants, 2,636 (28.2%) were aged 75 years and older, 3,332 (35.6%) were women, 5,399 (57.7%) were non-Hispanic white, 2,947 (31.5%) were black, and 984 (10.6%) were Hispanic. Cardiovascular disease was present in 1,877 persons (20.1%), and the Framingham 10-year CVD risk score was 15% and higher in 5,737 persons (61.3%). SPRINT was terminated early at 3.26 years due to overwhelming evidence of benefit. The SPRINT trial provided critical information on the efficacy and safety of lowering the SBP to < 120 mm Hg in elderly hypertensive adults. The primary outcome, myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, congestive heart failure, or cardiovascular death, was significantly lowered in the intensive BP management arm compared with the routine management arm (5.2% vs. 6.8%, hazard ratio [HR] 0.75, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.64–0.89; p < 0.0001). Thus, SPRINT demonstrated that a treatment goal for SBP of less than 120 mm Hg reduced incident CVD by 33% (from 3.85% to 2.59% per year) and totalmortality by 32% (from 2.63% to 1.78% per year) [32]. Overall, SPRINT demonstrated that intensive compared to standard SBP targets resulted in lower composite CVD outcomes and all-cause mortality in adults ≥ 75 years of age [33], however SPRINT was not a specific drug class study.

Consistent with the SPRINT cohort, the subgroup of participants aged ≥ 75 years also demonstrated impressive reductions in CVD events and total mortality with intensive as compared with standard therapy. The resultssupport and enhance the major SPRINT study findings in community-dwelling persons aged 75 years or older, demonstrating that a treatment goal for SBP of less than 120 mm Hg reduced incident CVD by 33% (from 3.85% to 2.59% per year) and total mortality by 32% (from 2.63% to 1.78% per year) ([33]). On the other hand, although elderly women are the predominant population with ISH, only 36% of the landmark SPRINT cohort were women and 28% of the entire SPRINT cohort were aged 75 years (the upper limit was age 80 years) [30].

Of note, the BP in SPRINT was measured using automated oscillometric blood pressure versus using manual (auscultatory) blood pressure, which was the technique used in other trials and which is more commonly used in routine practice than AOBP. Thus, the reported SPRINT SBP may be higher than usual clinic measurements.

Additionally, in SPRINT, diastolic pressures were greater than 70 mm Hg at baseline, and remained above 65 mm Hg during the course of the trial, even with intensive treatment. Given the concern for many older adults with isolated systolic hypertension experiencing low diastolic pressure (i.e., less than 60–65 mmHg), especially with coronary artery disease, aggressive lowering of the systolic pressure, may exacerbate myocardial ischemia and increase risk. Although there were increased adverse events with intensive BP lowering in SPRINT, such as syncope (2.3% versus 1.7%) and hyponatremia (3.8% versus 2.1%), the rates of orthostatic hypotension and falls resulting in hospitalization were similar between the groups.

From 2011 to 2017, according to the hypertension guidelines from the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, the American Geriatrics Society, the American Society for Preventive Cardiology, the American Society of Hypertension, the American Society of Nephrology, the Association of Black Cardiologists, and the European Society of Hypertension collectively recommended that the BP goals be lowered to less than 140/90 mm Hg in older persons younger than 80 years and to 140–145/<90 mm Hg, if tolerated in adults aged 80 years and older [3]. In addition, the Canadian 2016 hypertension guidelines recommend that high-risk adults aged 50 years and older with a SBP of 130 mmHg or higher obtained by an AOBP measurement should have a target SBP goal of 120 mmHg or lower [34].

The recent 2016 Canadian Hypertension Education Program (CHEP) Guidelines recommend intensive BP reduction in high risk patients, including, clinical or subclinical CVD or chronic kidney disease (nondiabetic nephropathy, proteinuria <1 g/d, estimated glomerular filtration rate 20–59 mL/min/1.73 m2) or estimated 10-year global cardiovascular risk ≥15% or age ≥ 75 years [18]. However, even CHEP maintains in the very elderly (age ≥ 80 years), the SBP target is <150 mm Hg. Nevertheless, for high-risk patients, intensive management to a target SBP 120 mm Hg should be guided by AOBP measurements, not usual clinic measurements. Finally, patients should be prepared for more clinical encounters, monitoring, and medication usage, as individuals who received intensive treatment in SPRINT were followed monthly until target BP levels were achieved. On average, SPRINT participants were prescribed 2.7 antihypertensive agents, compared with 1.8 agents in the standard control group. Therefore, although SBP targets <120 mm Hg are beneficial in certain cases, intensive treatment also incurs greater health care utilization and potential treatment risks and should be closely monitored.

Sub-Studies from SPRINT: Prediabetes, Chronic Kidney Disease, Cognition

Given the strength of the rigorously conducted randomized controlled SPRINT study design with adjudicated outcomes in a large, racially diverse population allowed for large subgroups of those with prediabetes and those with fasting normoglycemia at baseline. Recent sub-group analysis in SPRINT revealed lower risk in outcomes in those with prediabetes [35]. Accordingly, the beneficial effects of intensive SBP treatment on CVD events and all-cause mortality continued to patients with prediabetes and were similar among those with prediabetes and fasting normoglycemia.

Among SPRINT patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and hypertension without diabetes, a target SBP of 120 mm Hg compared to 140 mm Hg reduced rates of major CV events and all-cause death without evidence of effect modifications by CKD or deleterious effect on the main kidney outcome. Thus, demonstrating the best available evidence to date in favor of intensive SBP reduction as a means to improve survival in patients with CKD and hypertension who are burdened with very high mortality rate [36].

Overall, data demonstrate that antihypertensive drug therapy either significantly or insignificantly reduces the incidence of dementia or of cognitive impairment [37,38,39] despite the short follow-up of the double-blind antihypertensive drug versus placebo trials on the incidence of dementia and cognitive impairment. The SPRINT study suggests that target SBP levels of lower than 140 mm Hg and possibly 120 mm Hg or lower extend to cognitive outcomes as well. According to Hajjar et al. [40], patients 70 years of age or older who receive hypertension treatment, a SPRINT SBP level of 120 mm Hg or lower was not associated with worsening cognitive outcome and may be superior to the JNC-8P target for cognition. Thus, the findings suggest that a lower SBP target for African American patients specifically is linked to greater cognitive benefit.

Best Antihypertensive Agents in the Elderly

Adoption of healthy lifestyles is critical to prevent high BP and isthe bedrock of BP management and control. According to the JNC 7, major lifestyle modifications shown to lower BP include weight reduction in those individuals who are overweight or obese, adoption of Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) eating plan, dietary sodium reduction, physical activity, moderation of alcohol consumption, and smoking cessation, if applicable. The initiation of any antihypertensive agent dose should start low, and be up-titrated slowly while reducing BP gradually. Given the increased risk for hypotension and orthostatic hypotension, a single antihypertensive agent should be initiated at a time with careful monitoring of blood pressure. A strategy of initiating two drugs at low doses when the baseline BP is > 20 mm Hg above goal may be used cautiously, taking care to avoid overaggressive BP lowering especially given the frailty of the population.

Based upon evidence-based guidelines performed in patients aged ≥ 60 years, the antihypertensive treatment to be implemented in older hypertensive subjects are the same drug classes that are recommended for younger patients (i.e., diuretics, angiotensin receptor antagonist (ARB’s), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I), and calcium channel blockers, with an extension to β-blockers in the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Society of Hypertension (ESH)guidelines) [3, 41]. The choice of the specific antihypertensive agentin the treatment of elderly persons with hypertension depends on efficacy, tolerability, presence of specific comorbidities and cost [3]. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitionor ARB is a reasonable initial approach, especially if there is concurrent CVD, diabetes, proteinuria, chronic kidney disease, or heart failure. According to the ESC/ESH guideline, a calcium antagonist or diuretic in elderly patients with ISH is recommended [42]. Consistent with ESC/ESH guidelines, the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) data, also suggested that low-dose daily diuretic (chlorthalidone) is the most effective agent in this population [43]. On the other hand, hyponatremia is a valid consideration in elderly patients as many patients’ free water intake is reduced. After 1 year of treatment, 7.2% of the participants randomized to chorthalidonetreatment had a serum potassium < 3.5 mmol/L compared with 1% of the participants randomized to placebo after 1 year. However, with addition of an ACEI/ARB and/or aldosterone antagonist, the hypokalemia can be ameliorated.

In the Scandinavian population, the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA), data revealed a significant overall mortality benefit in subjects aged >60 years when using a combination of calcium channel blocker (amlopdipine) and ACEI (perindopril) when compared to a beta-blocker (atenolol) and thiazide (bendr oflumethia zide (BFZ) regimen [44]. Therefore, a long-acting dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker as the initial agent for the elderly is a safe option, with the addition of an ACEI/ARB or low-dose thiazide diuretic to the calcium channel blocker, if needed. Table 6.3 provides a comparison of recommended target BP goals recommended by the 2011–2017 Hypertension Guidelines in the elderly.

Conclusion

Age is a powerful risk factor for hypertension complications, however the treatment of hypertension in the elderly is complex. The current recommendation of less than 140/90 mm Hg has been associated with dramatic reductions in HTN complications with BP reduction. Multiple trials have shown more appropriate treatment of hypertension in the elderly is safe and will decrease stroke, heart failure, myocardial infarction and all-cause mortality. There is sufficient evidence of benefit and limited risk of harm if BP targets of less than 140/90 mm Hg are recommended for elderly, especially in higher risk groups. Future guidelines may be affected by results of the SPRINT landmark study which demonstrates the benefits of intensive BP reduction in CV morbidity and mortality which extends to patients with CKD and prediabetes, and demonstrates no negative impact on cognition in those patients greater than or equal to 75 years of age.

Future Guidelines

Future hypertensive guidelines may be impacted by the robust outcomes from SPRINT and return the BP goals in elderly to less than 140 and perhaps even lower.

2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/American Academy of Physician Assistants/Association of Black Cardiologists/American College of Preventative Medicine/American Geriatrics Society/American Pharmacists Association/American Society of Hypertension/American Society for Preventative Cardiology/National Medical Association/Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults.

References

Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135;e146–e603. Available from https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485

Bromfield SG, Bowling CB, Tanner RM, Peralta CA, Odden MC, Oparil S, Muntner P. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control among US adults 80 years and older, 1988-2010. J ClinHypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:270–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.12281.

Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, Artinian NT, Bakris G, Brown AS, et al. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on clinical expert consensus documents developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology, Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(20):2037–114.

Oparil S. Sy 11-3 hypertension in women: more dangerous than in men? J Hypertens. 2016;34:e366.

Lloyd-Jones DM, Evans JC, Levy D. Hypertension in adults across the age spectrum: current outcomes and control in the community. JAMA. 2005;294:466–72.

Ashman JJ, Rui P, Schappert SM. Age differences in visits to office-based physicians by adults with hypertension: United States, 2013, NCHS data brief, no 263. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016.

Bumgarner J. The health of the presidents: the 41 United States Presidents through 1993 from a physician’s point of view. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc; 1994.

Wang Ji G, Staessen JA, Franklin SS, et al. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure lowering as determinants of cardiovascular outcome. Hypertension. 2005;45:907–13.

O'Rourke MF, Nichols WW. Aortic diameter, aortic stiffness, and wave reflection increase with age and isolated systolic hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45:652–8.

Franklin SS, Jacobs MJ, Wong ND, et al. Predominance of isolated systolic hypertension among middle-aged and elderly US hypertensives: analysis based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III. Hypertension. 2001;37:869–74.

Liu X, Rodriguez CJ, Wang K. Prevalence and trends of isolated systolic hypertension among untreated adults in the United States. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2015;9(3):197–205.

Choi HY, Park HC, Ha SK. Salt sensitivity and hypertension: a paradigm shift from kidney malfunction to vascular endothelial dysfunction. Electrolytes Blood Press. 2015;13(1):7–16.

Chisholm P, Anpalahan M. Orthostatic hypotension: pathophysiology, assessment, treatment and the paradox of supine hypertension. Intern Med J. 2017;47:370–9.

FDA Consumer report website. Accessed 5 Aug 2017.: https://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm402287.htm#cuff.

Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2005;142–61(5):45.

Million Hearts. Available at: http://millionhearts.hhs.gov., 2017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Self-measured blood pressure monitoring: actions steps for clinicians. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2014. https://millionhearts.hhs.gov/files/MH_SMBP_Clinicians.pdf.

Leung AA, Nerenberg K, Daskalopoulou SS, McBrien K, Zarnke KB, Dasgupta K, Cloutier L, Gelfer M, Lamarre-Cliche M, Milot A, Bolli P. Hypertension Canada’s 2016 Canadian Hypertension Education Program Guidelines for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(5):569–88.

Kang Y-Y, Wang J-G. The J-curve phenomenon in hypertension. Pulse. 2016;4(1):49–60. https://doi.org/10.1159/000446922.

McEvoy JW, Chen Y, Rawlings A, Hoogeveen RC, Ballantyne CM, Blumenthal RS, Coresh J, Selvin E. Diastolic blood pressure, subclinical myocardial damage, and cardiac events: implications for blood pressure control. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(16):1713–22.

Amery A, Birkenhager W, Brixko P, Bulpitt C, Clement D, de Leeuw P, et al. Influence of antihypertensive drug treatment on morbidity and mortality in patients over the age of 60 years. EWPHE results: sub-group analysis based on entry stratification. J Hypertens. 1986;4:S642–7.

Staessen J, Bulpitt C, Clement D, De Leeuw P, Fagard R, Fletcher A, et al. Relation between mortality and treated blood pressure in elderly patients with hypertension: report of the European working party on high blood pressure in the elderly. BMJ. 1989;298:1552–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.298.6687.1552.

Dahlöf B, Hansson L, Lindholm LH, Schersten B, Ekbom T, Wester PO. Morbidity and mortality in the Swedish trial in old patients with hypertension (STOP-hypertension). Lancet. 1991;338(8778):1281–5.

SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the systolic hypertension in the elderly program (SHEP). JAMA. 1991;265:3255–64. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.265.24.3255.

Party MW. Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults: principal results. BMJ. 1992;304(6824):405–12.

Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, Celis H, Arabidze GG, Birkenhäger WH, Bulpitt CJ, De Leeuw PW, Dollery CT, Fletcher AE, Forette F. Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension. Lancet. 1997;350(9080):757–64.

Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1887–98. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0801369.

Verdecchia P, Staessen JA, Angeli F, et al. Usual versus tight control of systolic blood pressure in non-diabetic patients with hypertension (Cardio-Sis): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2009;374:525–33.

James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2013;311:507–20.

Wenger NK, Ferdinand KC, Merz CN, Walsh MN, Gulati M, Pepine CJ. Women, hypertension, and the systolic blood pressure intervention trial. Am J Med. 2016;129(10):1030–6.

Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R, Humphrey LL, Frost J, Forciea MA, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in adults aged 60 years or older to higher versus lower blood pressure targets: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of family physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:430–7. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-1785.

Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. SPRINT research group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103–16.

Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥75 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(24):2673–82.

Padwal R, Rabi DM, Schiffrin EL. Recommendations for intensive blood pressure lowering in high-risk patients, the Canadian view- point. Hypertension. 2016;68:3–5.

Bress AP, King JB, Kreider KE, Beddhu S, Simmons DL, Cheung AK, SPRINT Research Group et al. Effect of intensive versus standard blood pressure treatment according to baseline prediabetes status: a post Hoc Analysis of a Randomized Trial. Diabetes Care. 2017. pii: dc170885. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc17-0885.

Cheung AK, Rahman M, Reboussin DM, Craven TE, Greene T, Kimmel PL, SPRINT Research Group, et al. Effects of intensive BP control in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2017;28:2812–23 . ASN2017020148; published ahead of print June 22, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2017020148.

Forette F, Seux ML, Staessen JA, et al. The prevention of dementia with antihypertensive treatment. New evidence from the Systolic Hypertension in Europe (SYST-EUR) study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2046–52.

Tzourio C, Anderson C, Chapman N, et al. Effects of blood pressure lowering with perindopril and indapamide therapy on dementia and cognitive decline in patients with cerebrovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1069–75.

Peters R, Beckett N, Forette F, et al. Incident dementia and blood pressure lowering in the hypertension in the very elderly trial cognitive function assessment (HYVET-COG): a double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:683–9.

Hajjar I, Rosenberger KJ, Kulshreshtha A, et al. Association of JNC-8 and SPRINT systolic blood pressure levels with cognitive function and related racial disparity. JAMA Neurol. 2017.;Epub ahead of print;74:1199–205.

Benetos A, Bulpitt CJ, Petrovic M, Ungar A, Rosei EA, Cherubini A, Redon J, Grodzicki T, Dominiczak A, Strandberg T, Mancia G. An expert opinion from the European Society of Hypertension–European Union Geriatric Medicine Society Working Group on the management of hypertension in very old, frail subjects. Hypertension. 2016;67(5):820–5.

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens. 2013;31:1281–357.

The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: he Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288:2981–97.

Dahlöf B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian cardiac outcomes trial- blood pressure lowering arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomized control trial. Lancet. 2005;366:895–906.

Yoon SS, Fryar CD, Carroll MD. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2011–2014, NCHS data brief, no 220. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015.

Aronow WS. Managing hypertension in the elderly: What is different, what is the same? Curr. Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2017;11(8):22.

Wright JT, Fine LJ, Lackland DT, Ogedegbe G, Dennison Himmelfarb CR. Evidence supporting a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 150 mm Hg in patients aged 60 years or older: the minority view. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:499–503.

Krakoff LR, Gillespie RL, Ferdinand KC, et al. Hypertension recommendations from the eighth joint national committee panel members raise concerns for elderly black and female populations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(4):394–402.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Nasser, S.A., Ferdinand, K.C. (2019). Hypertension Management in the Elderly. In: Papademetriou, V., Andreadis, E., Geladari, C. (eds) Management of Hypertension. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92946-0_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92946-0_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-92945-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-92946-0

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)