Opinion statement

The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly recommends that the blood pressure be reduced to less than 140/90 mmHg in adults aged 60–79 years and the systolic blood pressure to 140 to 145 mmHg if tolerated in adults aged 80 years and older. I strongly support these guidelines based on clinical trial data, especially from the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly trial and from the Hypertension in the Very Elderly trial (HYVET). Other guidelines supporting reducing the blood pressure to less than 140/90 mmHg in adults aged 60 to 79 years of age include the European Society of Hypertension (ESH)/European Society of Cardiology (ESC) 2013 guidelines, the minority report from the 2013 Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) guidelines, the 2013 Canadian Hypertension Education Program guidelines, the 2011 UK guidelines, the 2014 American Society of Hypertension (ASH)/International Society of Hypertension (ISH) guidelines, and the 2015 AHA/ACC/ASH scientific statement on treatment of hypertension in patients with coronary artery disease. I support these guidelines. In adults aged 80 years and older, a blood pressure below 150/90 mm Hg has been recommended by these guidelines, with a target goal of less than 140/90 mmHg considered in those with diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease. I support these guidelines. The 2013 JNC 8 guidelines recommend reducing the blood pressure to less than 140/90 mmHg in adults aged 60 years and older with diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease but to less than 150/90 mmHg in adults aged 60 years and older without diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease. I strongly disagree with this recommendation and am very much concerned that the higher systolic blood pressure goal recommended by JNC 8 guidelines in adults aged 60 years and older without diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease will lead to an increase in cardiovascular events and mortality in these adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease in elderly adults [1•]. Hypertension occurs in 69 % of adults with a first myocardial infarction [2], in 77 % of adults with a first stroke [2], in 74 % of adults with congestive heart failure [2], and in 60 % of elderly adults with peripheral arterial disease [3]. Hypertension is also a major risk factor in elderly adults for dissecting aortic aneurysm, sudden cardiac death, angina pectoris, chronic kidney disease, left ventricular hypertrophy, thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, the metabolic syndrome, vascular dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and ophthalmologic disorders [1•]. Elderly adults with hypertension are more likely to have target organ damage and to develop new cardiovascular events [1•]. Blood pressure is adequately controlled in only 28 % of women and in 36 % of men aged 60 to 79 years and in only 23 % of women and 38 % of men aged 80 years and older [4].

The 2003 guidelines report from the seventh report of the Joint National Committee (JNC 7) on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure recommended that the target blood pressure in adults without diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease be less than 140/90 mmHg [5]. In the absence of randomized control data, these guidelines recommended that patients with diabetes mellitus or with chronic kidney disease should have their blood pressure lowered to less than 130/80 mmHg [5].

In the absence of randomized control data, the AHA 2007 guidelines recommend that adults with hypertension at high risk for coronary events such as those with coronary artery disease, a coronary artery risk equivalent, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, or a 10 -year Framingham risk score of 10 % or higher should have their blood pressure lowered to less than 130/80 mmHg [6]. These guidelines also recommended that adults with hypertension and left ventricular dysfunction should have their blood pressure reduced to less than 120/80 mmHg [6].

These guidelines needed to be updated [7]. Clinical studies that favored a blood pressure goal of less than 140/90 mmHg in patients at high risk for coronary events rather than the blood pressure goal recommended by the 2007 AHA guidelines included the following studies [8–18].

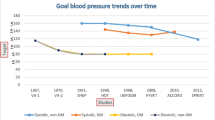

This paper will discuss the blood pressure guidelines recommendations from 2011 through 2015.

Target blood pressure goals recommended from 2011 through 2015

The ACC/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly was developed in association with the American Academy of Neurology, the American Geriatrics Society, the American Society for Preventive Cardiology, the ASH, the American Society of Nephrology, the Association of Black Cardiologists (ABC), and the ESH/ESC. This document recommends that the blood pressure be reduced to less than 140/90 mmHg in adults aged 60–79 years and the systolic blood pressure reduced to 140 to 145 mmHg if tolerated in adults aged 80 years and older [1•]. I strongly support these guidelines based on clinical trial data, especially from the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly trial [19–21] and from the Hypertension in the Very Elderly trial (HYVET) [22]. In HYVET, 3845 adults aged 80 years and older with a systolic blood pressure of 160 mmHg or higher were randomized to indapamide with perindopril added if needed or to placebo [22]. The lowest blood pressure achieved was 143 mmHg. At 1.8-year median follow-up, compared with placebo, anti-hypertensive drug therapy decreased fatal or non-fatal stroke by 30 % (p = 0.06), fatal stroke by 39 % (p = 0.05), all-cause death by 21 % (p = 0.02), cardiovascular death by 23 % (p = 0.06), and heart failure by 64 % (p < 0.001) [22].

The 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for management of hypertension recommend reducing the systolic blood pressure to less than 140 mmHg in adults aged 60 to 79 years [23•]. In adults aged 80 years and older with a systolic blood pressure of 160 mmHg or higher, the systolic blood pressure should be decreased to between 140 and 150 mmHg provided they are in good physical and mental conditions [23•]. I support these guidelines.

The 2013 Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) guidelines for management of hypertension recommend reducing the systolic blood pressure in adults aged 60 years or older to less than 150 mmHg if they do not have diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease and to less than 140 mm Hg if they have diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease [24•]. I concur with the minority view from JNC 8 which recommends that the systolic blood pressure goal in adults aged 60 to 79 years with hypertension without diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease should be reduced to less than 140 mmHg [25•].

Elderly persons are currently being undertreated for hypertension [1•]. If the JNC 8 panel recommendations are used, 6 million patients in the USA aged 60 years and older would be ineligible for treatment with anti-hypertensive drug therapy and treatment intensity would be reduced for an additional 13.5 million elderly persons [26], causing increased incidences of coronary events, stroke, heart failure, cardiovascular mortality, and other adverse events associated with inadequate control of hypertension.

The Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study is an observational study of the incidence of stroke in adults living in the stroke belt and stroke buckle regions of the USA [27]. This study included 4181 adults aged 55–64 years, 3737 adults aged 65–74 years, and 1839 adults aged 75 years and older on anti-hypertensive drug therapy. Median follow-up was 4.5 years for coronary heart disease or stroke and for coronary heart disease, 5.7 years for stroke, and 6.0 years for all-cause mortality. We found that the optimum blood pressure for elderly patients on anti-hypertensive therapy for reduction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in this study was less than 140/90 mmHg [27].

Among 8354 adults aged 60 years and older with coronary artery disease in the International VErapamil SR Trandolapril (INVEST) study, a baseline systolic blood pressure of 150 mmHg and higher, and 22,308 patient years of follow-up, 57 % had a systolic blood pressure less than 140 mmHg, 21 % had a systolic blood pressure of 140 to 149 mmHg, and 22 % had a systolic blood pressure of 150 mmHg and higher [28]. The primary outcome of all-cause mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, or non-fatal stroke occurred in 9.36 % of adults with a systolic blood pressure of less than 140 mmHg, in 12.71 % of adults with a systolic blood pressure of 140–149 mmHg, and in 21.3 % of adults with a systolic blood pressure of 150 mmHg and higher (p < 0.0001) [28]. Using propensity score analyses, compared with a systolic blood pressure of less than 140 mmHg, a systolic blood pressure of 140 to 149 mmHg increased cardiovascular mortality by 34 % (p = 0.04), total stroke by 89 % (p = 0.002), and non-fatal stroke by 70 % (p = 0.03) [28]. Compared with a systolic blood pressure of less than 140 mmHg, a systolic blood pressure of 150 mmHg and higher increased the primary outcome by 82 % (p < 0.0001), all-cause mortality by 60 % (p < 0.0001), cardiovascular mortality by 218 % (p < 0.0001), and total stroke by 283 % (p < 0.0001) [28].

The ABC and the Working Group on Women’s Cardiovascular Health 2014 recommendations also support a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 140 mmHg in adults aged 60 years and older and of less than 150 mmHg in debilitated or frail persons aged 80 years and older [29•]. The ABC recommendations state that the JNC 8 recommendations may endanger the more than 36 million Americans with hypertension who are aged 60 years and older with a disproportionate negative effect on blacks and those with chronic kidney disease and cerebrovascular disease. The Working Group on Women’s Cardiovascular Health 2014 recommendations state that hypertension is the major modifiable risk factor causing coronary heart disease, heart failure, stroke, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease in women. This group states that the JNC 8 guidelines do not recognize that the hypertensive population is primarily women, that older women generally have poor control of hypertension, and that approximately 40 % of those with poor blood pressure control are black women who have the highest risks for stroke, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease [29•]. I strongly support their recommendations.

The 2011 UK guidelines recommend reducing the systolic blood pressure to less than 140 mmHg in adults younger than 80 years [30•]. The 2013 Canadian Hypertension Education Program guidelines recommend reducing the systolic blood pressure to less than 140 mmHg in adults younger than 80 years of age and to less than 150 mmHg in adults aged 80 years and older [31•]. I support these guidelines.

The 2014 ASH/ISH guidelines recommend reducing the blood pressure to less than 140/90 mmHg in adults aged 80 years and younger [32•]. These guidelines recommend lowering the blood pressure in adults older than 80 years of age with a blood pressure of 150/90 mmHg or higher to less than 150/90 mmHg unless these persons have diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease when a target goal of less than 140/90 mmHg should be considered [32•]. I support these guidelines.

The AHA/ACC/ASH 2015 guidelines on treatment of hypertension in adults with coronary artery disease are the most recently published hypertension guidelines [33•]. These guidelines recommend that the optimal blood pressure in adults with coronary artery disease is less than 140/90 mmHg [33•]. I am a coauthor of these guidelines [33•].

Lifestyle measures

Lifestyle measures should be encouraged both to retard development of hypertension and as adjunctive therapy in persons with hypertension. A meta-analysis of 56 randomized controlled trials showed that the mean blood pressure was lowered at 3.7/0.9 mmHg for a 100-mmol/day decrease in sodium excretion [34]. Many studies have demonstrated that dietary sodium reduction reduces cardiovascular events [35–39]. The Health Survey for England reported that from 2003 to 2011, salt intake measured by 24 h urinary sodium decreased by 1.9 g/day (p < 0.01), blood pressure in adults not on anti-hypertensive medication was reduced to 2.7/1.1 mmHg (p < 0.001), mortality from stroke was decreased to 42 % (p < 0.001), and mortality from ischemic heart disease was decreased to 40 % (p < 0.001) [39].

Guidelines recommend no more than 2300 mg of sodium (6 g of sodium chloride daily) and no more than 1500 mg of sodium daily in black adults, elderly adults, and adults with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease [40]. Decrease of dietary sodium intake by lowering sodium content in processed food and by not adding salt to food would lead to a lowering of blood pressure and to lowering cardiovascular events and mortality. A national salt reduction program is one of the simplest and most cost-effective ways of improving public health.

Other lifestyle measures for treating hypertension and prehypertension include weight control, smoking cessation, aerobic physical activity, decrease in dietary fat and cholesterol, adequate dietary potassium, calcium, and magnesium intake, avoidance of excessive alcohol intake (no more than 1 oz daily in men and 0.5 oz daily in women and light-weight men), avoidance of excessive caffeine, and by avoiding drugs which increase blood pressure such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [1•, 5].

Anti-hypertensive drug therapy

A meta-analysis of 147 randomized trials of 464,000 adults with hypertension reported that except for the extra protective effect of beta blockers given after myocardial infarction and a minor additional effect of calcium channel blockers (CCBs) in preventing stroke, beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), diuretics, and CCBs caused a similar decrease in coronary events and stroke for a given reduction in blood pressure [41]. The proportionate reduction in cardiovascular events was the same or similar regardless of pretreatment blood pressure and the presence or absence of cardiovascular events [41]. If beta blockers are used to treat elderly adults with hypertension, atenolol should not be used [42–44].

The ACC/AHA 2011 guidelines recommend that the choice of anti-hypertensive drug therapy in elderly adults such as diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta blockers, and CCBs depends on efficacy, tolerability, presence of specific comorbidities, and cost [1•]. I strongly support these guidelines.

The 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines recommend using diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta blockers, or CCBs as anti-hypertensive drug therapy in elderly adults [23•]. However, diuretics and CCBs may be preferred for treating isolated systolic hypertension in elderly adults [23•].

The JNC 8 guidelines recommend as initial anti-hypertensive drug therapy in the general non-black population diabetic thiazide-type diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or CCBs [24•]. These guidelines recommend as initial anti-hypertensive drug therapy in the general black population diabetic thiazide-type diuretics or CCBs [24•] and in persons with chronic kidney disease ACE inhibitors or ARBs. ACE inhibitors and ARBs may not be used together to treat hypertension [24•].

The 2014 ASH/ISH guidelines recommend when hypertension is the only or main condition, in elderly black adults that the first anti-hypertensive drug should be a thiazide-type diuretic or CCB [32•]. If a second anti-hypertensive drug is needed, an ACE inhibitor or ARB should be added. If a third anti-hypertensive drug is needed, a CCB plus a thiazide-type diuretic plus an ACE inhibitor or ARB should be used [32•]. When hypertension is the only or main condition, in elderly white and other non-black adults, the first anti-hypertensive drug should be a thiazide-type diuretic or CCB [32•]. If a second anti-hypertensive drug is needed, an ACE inhibitor or ARB should be added. If a third anti-hypertensive drug is needed, a CCB plus a thiazide-type diuretic plus an ACE inhibitor or ARB should be given [32•].

When hypertension is present in elderly adults with diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease, the first anti-hypertensive drug should be an ACE inhibitor or ARB [32•]. If a second anti-hypertensive drug is needed, a CCB or thiazide-type diuretic should be added. If a third anti-hypertensive drug is needed, a CCB plus a thiazide-type diuretic plus an ACE inhibitor or ARB should be given [32•]. When hypertension is present in elderly adults with coronary artery disease, initial anti-hypertensive drug therapy should be a beta blocker plus an ACE inhibitor or ARB [32•]. If additional anti-hypertensive drug therapy is needed, a CCB or thiazide-type diuretic should be added. If additional anti-hypertensive drug is needed, a beta blocker plus an ACE inhibitor or ARB plus a CCB plus a thiazide-type diuretic should be used [32•].

When hypertension is present in elderly adults with a history of stroke, the first anti-hypertensive drug prescribed should be an ACE inhibitor or ARB [32•]. If a second anti-hypertensive drug is needed, a CCB or thiazide-type diuretic should be added. If a third anti-hypertensive drug is needed, an ACE inhibitor or ARB plus a CCB plus a thiazide-type diuretic should be given [32•]. Elderly adults with hypertension and congestive heart failure should be treated with an ACE inhibitor or ARB plus a beta blocker such as carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, or bisoprolol plus a diuretic plus an aldosterone antagonist if indicated [32•]. I concur with these recommendations [32•].

The AHA/ACC/ASH 2015 guidelines on treatment of hypertension in adults with coronary artery disease recommend that patients with coronary artery disease and hypertension should be treated with beta blockers plus ACE inhibitors as the drugs of first choice with addition of CCBs or thiazide-type diuretics as needed to lower the blood pressure to less than 140/90 mmHg [33•]. I strongly support these guidelines.

Frail elderly

Randomized clinical trial studies on treatment of hypertension in frail elderly adults have not been performed [45]. The Predictive Values of Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness in Institutionalized Very Aged Population (PARTAGE) study was a longitudinal study performed in 1130 frail adults aged 80 years and older (mean age 88 years) living in nursing homes in Italy and France [46]. This study reported a 78 % increase in mortality in frail elderly adults with a systolic blood pressure below 130 mmHg receiving 2 or more anti-hypertensive drugs (32.2 %) compared with frail elderly adults with a systolic blood pressure below 130 mmHg treated with 0–1 anti-hypertensive drug (19.7 %; p < 0.001) [46]. Randomized clinical anti-hypertensive drug studies have demonstrated a J-shaped relationship between systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure with all-cause mortality, fatal and non-fatal stroke, and congestive heart failure in the general population of adults who have hypertension as well as in populations with hypertension at high risk for cardiovascular events [47]. Overtreatment of hypertension as well as inadequate control of hypertension may cause adverse clinical outcomes in frail elderly persons [45]. Until adequate clinical trial data are available for treating hypertension in frail elderly adults, I suggest following the guidelines recommended by the ACC/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly [1•] and the other recent hypertension guidelines [23•, 25•, 29•, 30•, 31•, 32•, 33•] except for JNC 8 [24•].

Renal artery stenosis

The commonest cause of secondary hypertension in elderly adults is renal artery stenosis [48]. Although uncontrolled studies suggested renal artery angioplasty or stenting in adults with renal artery stenosis with hypertension reduced systolic blood pressure and stabilized chronic kidney disease, randomized, controlled trials of renal artery angioplasty have not found that this procedure is efficacious in lowering blood pressure [49–51].

Resistant hypertension

Resistant hypertension is a blood pressure remaining above goal despite use of three optimally dosed anti-hypertensive drugs from different classes, with one of the three drugs being a diuretic [52]. A normal home blood pressure or 24 h ambulatory blood pressure excludes resistant hypertension [53, 54]. Poor patient compliance, inadequate doses of anti-hypertensive drugs, inadequate choice of combinations of anti-hypertensive drugs, poor office blood pressure measurement technique, and having to pay for costs of drugs are factors associated with pseudo-resistant hypertension [1•, 53, 55]. Factors contributing to resistant hypertension include excess sodium dietary intake, excess alcohol intake, obesity, use of cocaine, amphetamines, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, contraceptive hormones, adrenal steroid hormones, sympathomimetic drugs (nasal decongestants and diet pills), erythropoietin, licorice, ephedra, progressive renal disease inadequate treatment with diuretics, and secondary causes of resistant hypertension [1•, 48, 53]. Some data support the use of spironolactone as a fourth anti-hypertensive drug to treat resistant hypertension if the serum potassium level is 4.5 mmol/l or lower [53, 56].

Renal sympathetic denervation

Inadequately controlled studies reported that renal sympathetic denervation was very effective in lowering blood pressure in adults with resistant hypertension [57–59]. An international expert consensus statement recommended considering renal sympathetic denervation in patients whose blood pressure could not be controlled by lifestyle modification plus drug therapy tailored to current guidelines [60]. The Symplicity HTN-3 study randomized 535 patients with resistant hypertension in a 2:1 ratio to renal sympathetic denervation or a sham procedure [61]. This study demonstrated that renal sympathetic denervation was not more effective than the sham procedure in reducing office systolic blood pressure or 24 h ambulatory systolic blood pressure at 6 months [61], 24 h ambulatory blood pressure in either the 24 h or day and night periods at 6 months [62], and office systolic blood pressure or 24 h ambulatory systolic blood pressure at 1 year [63].

Conclusion

Lifestyle measures should be encouraged both to retard development of hypertension and as adjunctive therapy in persons with hypertension. The ACCAHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly recommends that the blood pressure be reduced to less than 140/90 mmHg in adults aged 60–79 years and the systolic blood pressure to 140 to 145 mmHg if tolerated in adults aged 80 years and older [1•]. I strongly support these guidelines. I also support the 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines [23•], the minority report from JNC 8 [25•], the ABC and the Working Group on Women’s Cardiovascular Health 2014 recommendations [29•], the 2011 UK guidelines [30•], the 2013 Canadian Hypertension Education Program guidelines [31•], the 2014 ASH/ISH guidelines [32•], and the 2015 AHA/ACC/ASH guidelines [33•]. I strongly disagree with the 2013 JNC 8 guidelines recommending reducing the systolic blood pressure to less than 150 mmHg rather than to less than 140 mmHg in adults aged 60 years and older without diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease and am very much concerned that their higher systolic blood pressure goal will lead to an increase in cardiovascular events and mortality in these adults. The ACC/AHA 2011 guidelines recommend that the choice of anti-hypertensive drug therapy in elderly adults such as diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta blockers, and CCBs depends on efficacy, tolerability, presence of specific comorbidities and cost [1•]. I strongly support these guidelines. Overtreatment of hypertension as well as inadequate control of hypertension may cause adverse clinical outcomes in frail elderly persons [45]. Until adequate clinical trial data are available for treating hypertension in frail elderly adults, I suggest following the guidelines recommended by the ACC/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly [1•] and the other recent hypertension guidelines [23•, 25•, 29•, 30•, 31•, 32•, 33•] except for JNC 8 [24•].

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, et al. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. Developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology, Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2037–114. These guidelines recommend that the systolic blood pressure be reduced to less than 140 mm Hg in adults aged 60–79 years and to 140 to 145 mm Hg if tolerated in adults aged 80 years and older.

Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:e21–e181.

Aronow WS, Ahmed MI, Ekundayo OJ, et al. A propensity-matched study of the association of PAD with cardiovascular outcomes in community-dwelling older adults. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:130–5.

Lloyd-Jones DM, Evans JC, Levy D. Hypertension in adults across the age spectrum: current outcomes and control in the community. JAMA. 2005;294:466–72.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. The JNC 7 Report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–72.

Rosendorff C, Black HR, Cannon CP, et al. Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2007;115:2761–88.

Aronow WS. Hypertension guidelines. Hypertension. 2011;58:347–8.

Bangalore S, Qin J, Sloan S, et al. What is the optimal blood pressure in patients after acute coronary syndromes? relationship of blood pressure and cardiovascular events in the pravastatin or atorvastatin evaluation and infection therapy-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (PROVE IT-TIMI) 22 trial. Circulation. 2010;122:2142–51.

Cooper-DeHoff RM, Gong Y, Handberg EM, et al. Tight blood pressure control and cardiovascular outcomes among hypertensive patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease. JAMA. 2010;304:61–8.

The ACCORD Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575–85.

Redon J, Mancia G, Sleight P, et al. Safety and efficacy of low blood pressures among patients with diabetes. Subgroup analyses from the ONTARGET (ONgoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:74–83.

Mancia G, Schumacher H, Redon J, et al. Blood pressure targets recommended by guidelines and incidence of cardiovascular and renal events in the Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination With Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET). Circulation. 2011;124:1727–36.

Appel LJ, Wright Jr JT, Greene T, et al. Intensive blood-pressure control in hypertensive chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:918–29.

Lazarus JM, Bourgoignie JJ, Buckalew VM, et al. Achievement and safety of a low blood pressure goal in chronic renal disease: the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Hypertension. 1997;29:641–50.

Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Loriga G, et al. Blood-pressure control for renoprotection in patients with nondiabetic chronic renal disease (REIN-2): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:939–46.

Upadhyay A, Earley A, Haynes SM, Uhlig K. Systematic review: blood pressure target in chronic kidney disease and proteinuria as an effect modifier. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:541–8.

Banach M, Bhatia V, Feller MA, et al. Relation of baseline systolic blood pressure and long-term outcomes in ambulatory patients with chronic mild to moderate heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1208–14.

Ovbiagele B, Diener H-C, Yusuf S, et al. Level of systolic blood pressure within the normal range and risk of recurrent stroke. JAMA. 2011;306:2137–44.

SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA. 1991;265:3255–64.

Perry Jr HM, Davis BR, Price TR, et al. Effect of treating isolated systolic hypertension on the risk of developing various types and subtypes of stroke. The Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA. 2000;284:465–71.

Kostis JB, Davis BR, Cutler J, et al. Prevention of heart failure by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. JAMA. 1997;278:212–6.

Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Eng J Med. 2008;358:1887–98.

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2159–219. These guidelines recommend reducig the systolic blood pressure to less than 140 mm Hg in adults aged 60 to 79 years and in adults aged 80 years and older with a systolic blood pressure of 160 mm Hg or higher to between 140–150 mm Hg provided they are in good physical and mental conditions.

James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults. Report from the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507–20. These guidelines recommend reducing the systolic blood pressure in persons aged 60 years or older to less than 150 mm Hg if they do not have diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease and to less than 140 mm Hg if they have diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease.

Wright Jr JT, Fine LJ, Lackland DT, et al. Evidence supporting a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 150 mm Hg in patients aged 60 years or older: the minority view. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:499–503. This minority report from JNC8 recommends that the systolic blood pressure goal in persons aged 60 to 79 years with hypertension without diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease should be reduced to less than 140 mm Hg.

Navar-Boggan AM, Pencina MJ, Williams K, et al. Proportion of US adults potentially affected by the 2014 hypertension guideline. JAMA. 2014;311:1424–9.

Banach M, Bromfield S, Howard G, et al. Association of systolic blood pressure levels with cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality among older adults taking antihypertensive medication. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176:219–26.

Bangalore S, Gong Y, Cooper-DeHoff RM, et al. 2014 Eighth Joint National Committee Panel recommendation for blood pressure targets revisited: results from the INVEST study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:784–93.

Krakoff LR, Gillespie RL, Ferdinand KC, et al. 2014 hypertension recommendations from the eighth joint national committee panel members raise concerns for elderly black and female populations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:394–402. The Association of Black Cardiologists and the Working Group on Women’s Cardiovascular Health support a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 140 mm Hg in persons aged 60 to 79 years and of less than 150 mm Hg in debilitated or frail persons aged 80 years and older.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Hypertension: clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2011. These guidelines recommend reducing the systolic blood pressure to less than 140 mm Hg in adults younger than 80 years.

Hackam DG, Quinn RR, Ravani P, et al. The 2013 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:528–42. These guidelines recommend decreasing the systolic blood pressure to less than 140 mm Hg in adults s younger than 80 years of age and to less than 150 mm Hg in adults aged 80 years and older.

Weber MA, Schiffrin EL White WB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community. A statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. 2014;16:14–26. These guidelines recommend reducing the blood pressure to less than 140/90 mm Hg in adults aged 80 years and younger and to less than 150/90 mm Hg in adults older than 80 years unless these persons have diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease when a target goal of less than 140/90 mm Hg should be considered.

Rosendorff C, Lackland DT, Allison M, Aronow WS, et al. AHA/ACC/ASH scientific statement. Treatment of hypertension in patients with coronary artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Society of Hypertension. Circulation. 2015. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000207. These guidelines recommend that the optimal blood pressure in adults with coronary artery disease is less than 140/90 mm Hg.

Midgley JP, Matthew AG, Greenwood CM, Logan AG. Effect of reduced dietary sodium on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1996;275:1590–7.

Cook NR, Cutler JA, Obarzanek E, et al. Long-term effects of dietary sodium reduction on cardiovascular disease outcomes: observational follow-up of the trials of hypertension prevention (TOHP). BMJ. 2007;334:885–8.

Chang HY, Hu YW, Yue CS, et al. Effect of potassium-enriched salt on cardiovascular mortality and medical expenses of elderly men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1289–96.

Karppanen H, Mervaala E. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;49:59–75.

Yang Q, Liu T, Kuklina EV, et al. Sodium and potassium intake and mortality among US adults: prospective data from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1183–91.

He FJ, Pombo-Rodrigues S, Macgregor GA. Salt reduction in England from 2003 to 2011: its relationship to blood pressure, stroke and ischaemic heart disease mortality. BMJ Open. 2014;4, e004549. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004549.

US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture. Dietary guidelines for Americans. 6th ed. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office; 2005. January, 2005.

Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of BP lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1665. doi:10.1136/bmj.b1665.

Aronow WS. Might losartan reduce sudden cardiac death in diabetic patients with hypertension? Lancet. 2003;362:591–2.

Carlberg B, Samuelson O, Lindholm LH. Atenolol in hypertension: is it a wise choice? Lancet. 2004;364:1684–9.

Aronow WS. Current role of beta blockers in the treatment of hypertension. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:2599–607.

Aronow WS. Multiple blood pressure medications and mortality among elderly individuals. JAMA. 2015;313:1362–3.

Benetos A, Labat C, Rossignol P, et al. Treatment with multiple blood pressure medications, achieved blood pressure, and mortality in older nursing home residents: the PARTAGE study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed. 8012.

Banach M, Aronow WS. Blood pressure J curve. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2012;14:556–66.

Chiong JR, Aronow WS, Khan IA, et al. Secondary hypertension: current diagnosis and treatment. Int J Cardiol. 2008;124:6–21.

ASTRAL Investigators, Wheatley K, Ives N, et al. Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1953–62.

Bax L, Woittiez AJ, Kouwenberg HJ, et al. Stent placement in patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis and impaired renal function: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:840–8.

Cooper CJ, Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, et al. Stenting and medical therapy for atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:13–22.

Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S, et al. Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2008;117:e510–26.

Myat A, Redwood SR, Quereshi AC, et al. Resistant hypertension. BMJ. 2012;345, e7473. doi:10.1136/bmj.e7473 (published 20 November 2012).

Pimenta E, Calhoun DA. Resistant hypertension. Incidence, prevalence, and prognosis. Circulation. 2012;125:1594–6.

Gandelman G, Aronow WS, Varma R. Prevalence of adequate blood pressure control in self-pay or medicare patients versus medicaid or private insurance patients with systemic hypertension followed in a university cardiology or general medicine clinic. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:815–6.

Chapman N, Dobson J, Wilson S, et al. Effect of spironolactone on blood pressure in subjects with resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:839–45.

Symplicity HTN-1 Investigators. Catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation for resistant hypertension. Durability of blood pressure reduction out to 24 months. Hypertension. 2011;57:911–7.

Esler MD, Krum H, Schlaich M, et al. Renal sympathetic denervation for treatment of drug-resistant hypertension: one-year results from the Symplicity HTN-2 randomized, controlled trial. Circulation. 2012;126:2976–82.

Davis MI, Filion KB, Zhang D, et al. Effectiveness of renal denervation therapy for resistant hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:231–41.

Schlaich MP, Schmieder RE, Bakris G, et al. International expert consensus statement. Percutaneous transluminal renal denervation for the treatment of resistant hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:2031–45.

Bhatt DL, Kandzari DE, O’Neill WW, et al. A controlled trial of renal denervation for resistant hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:393–401.

Bakris GL, Townsend RR, Liu M, et al. Impact of renal denervation on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure: results from SYMPLICITY HTN-3. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1071–8.

Bakris GL, Townsend RR, Flack JM, et al. 12-month blood pressure results of catheter-based renal artery denervation for resistant hypertension: the SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1314–21.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Wilbert S. Aronow declares no potential conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Prevention

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aronow, W.S. Blood Pressure Goals and Targets in the Elderly. Curr Treat Options Cardio Med 17, 33 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-015-0394-x

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-015-0394-x