Abstract

Three studies (total n = 3576) employed latent profile analyses to identify how self-compassion and self-esteem are configured within individuals. Furthermore, these studies examined profile differences in intra-and interpersonal functioning. Self-compassion and self-esteem were assessed across the studies. In Study 1, participants recalled negative events and responded the scales of state self-compassion and self-improvement. In Study 2, participants completed a measure of basic psychological need satisfaction. In Study 3, participants completed the scales of social isolation and the quality of romantic relationships. Across the three studies, latent profile analyses indicated that individuals were classified into one of three latent profiles: Low Compassionate and Worthy Style (low self-compassion and self-esteem), Moderate Compassionate and Worthy Style (moderate self-compassion and self-esteem), or High Compassionate and Worthy Style (high self-compassion and self-esteem). These analyses did not reveal the groups of individuals who displayed high self-compassion and low self-esteem simultaneously, or vice versa. Furthermore, individuals with High Compassionate and Worthy Style reported higher levels of self-compassionate reactions toward distressing events, self-improvement orientation (Study 1), satisfaction with basic psychological needs (Study 2), and relationship satisfaction (Study 3). They also indicated lower levels of feeling lonely and ostracized, and fewer frequencies of psychological intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization (Study 3). Overall, these results suggest that self-compassion and self-esteem operate unitedly rather than separately within individuals to support positive intra-and interpersonal functioning. Thus, given the interactive network of self-compassion and self-esteem, interventions to boost self-compassion might also promote self-esteem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Research has illustrated that how individuals relate to themselves influences their affective, cognitive, and behavioral tendencies (Orth & Robins, 2022; Neff, 2023). Numerous studies have focused on self-esteem that reflects subjective appraisals of one’s worth as a person (Fraser et al., 2023; Orth & Robins, 2022). Meta-analyses of longitudinal research have provided evidence that high self-esteem is robustly associated with indicators of positive psychological functioning, including mental health, quality of social relationships, and academic and job performance (Harris & Orth, 2020; Orth & Robins, 2022). Therefore, high self-esteem is considered beneficial for human beings (Orth & Robins, 2022). Nonetheless, the desire to maintain and avoid dropping high levels of self-esteem tends to thwart such positive functioning because individuals often become preoccupied with the desire and fail at pursuing other important goals, such as learning from failures (Crocker & Park, 2012).

Neff (2003, 2011) initially proposed self-compassion as an alternative to pursuing high self-esteem and contrasted it with self-esteem. According to Neff (2003, 2011, 2023), self-compassion is a dynamic system of six elements that work holistically to alleviate suffering: increased self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness, and decreased self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification. The first three are subsumed under compassionate self-responding (CS) and the remaining elements under uncompassionate self-responding (UCS; Neff, 2023). Individuals’ levels of self-compassion are placed on a bipolar continuum of UCS and CS, with a neutral point in-between (Miyagawa & Neff, 2023; Neff, 2023; Phillips, 2021). Thus, self-compassionate individuals are theorized to treat themselves with kindness, understand their suffering as a part of common human experiences, and pay balanced attention to their thoughts and feelings (Neff, 2003, 2011, 2023). These individuals also tend to avoid being self-critical, feeling isolated in suffering, and becoming overwhelmed with negative thoughts and feelings (Neff, 2003, 2011, 2023). Thus, despite the similarity regarding positive attitude toward the self, self-compassion differs from self-esteem in that the former aims to alleviate suffering by increasing CS and reducing UCS (Neff, 2003, 2011, 2023).

Cumulative evidence has demonstrated that self-compassion has a wide range of psychological benefits (see Neff, 2023, for a review). For example, self-compassion was associated with high levels of well-being (Gunnell et al., 2017; Pandey et al., 2021) and the satisfaction of psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Gunnell et al., 2017). Self-compassion was also associated with harmonious social relationships (Lathren et al., 2021; Neff & Beretvas, 2013) and lower levels of feeling loneliness (Liu et al., 2022). These results have provided evidence that self-compassion is a healthy attitude toward self that enhances positive psychological functioning (Neff, 2011, 2023; Tiwari et al., 2020). Importantly, self-compassion is known to be associated with positive psychological functioning beyond self-esteem (Fraser et al., 2023; Neff, 2011). Research has illustrated that self-compassion is robustly associated with higher levels of self-improvement orientations (Zhang & Chen, 2016), and lower levels of contingencies of self-worth (Neff & Vonk, 2009), stress responses (Krieger et al., 2015), and partner violence (Neff & Beretvas, 2013), even when controlling for self-esteem. Overall, these results differentiate the influences of self-compassion and self-esteem.

Nonetheless, the correlation between self-compassion and self-esteem is typically strong (e.g., r = .62 to .68; Neff & Vonk, 2009), suggesting a conceptual overlap between them (Fraser et al., 2023; Neff, 2011). Through extensive reviews on research on self-compassion and self-esteem, Fraser et al. (2023) provided a new framework to capture the relationship between these concepts. Specifically, Fraser et al. (2023) proposed that self-compassion and self-esteem constitute an interactive network such that these two concepts work in tandem rather than separately within individuals. Furthermore, Fraser et al. (2023) claimed that the interactive network is ideographic; thus, individuals differ in qualitatively different configurations of self-compassion and self-esteem. Overall, self-compassion and self-esteem are theorized to operate holistically and the groups of individuals who display higher levels of these constructs are hypothesized to experience psychological flourishing (Fraser et al., 2023).

While research using variable-centered approaches such as regression analyses could illustrate whether self-compassion and self-esteem independently predicts outcomes, partialling out these constructs cannot identify how they interact within individuals (Ferguson et al., 2020; Keefer et al., 2012; Spurk et al., 2020). For example, Donald et al. (2018) used a cross-lagged panel model to examine the relationship between self-compassion and self-esteem in a sample of adolescents. They found that self-esteem was an antecedent of self-compassion but not vice versa, suggesting that a positive feeling of self-worth fostered a compassionate attitude toward the self. Although this approach highlighted the directionality of these constructs, it is still unclear about the intra-individual interactions between them (Keefer et al., 2012). In other words, variable-centered approaches often fail to illustrate the qualitatively different configurations of constructs (Spurk et al., 2020). To examine the interactive network model of self-compassion and self-esteem (Fraser et al., 2023), it is necessary to directly investigate the possible combinations of self-compassion and self-esteem within individuals.

Latent profile analyses are person-centered approaches that aim to clarify the configuration of constructs and classify individuals into heterogeneous groups, or latent profiles (Ferguson et al., 2020; Keefer et al., 2012; Spurk et al., 2020). These analyses allow to reveal the distinct combinations of constructs, clarify the size of each profile, and examine profile differences in other outcome variables (Bakk & Vermunt, 2016; Spurk et al., 2020). Therefore, latent profile analyses can contribute to the literature by detailing the relationship between self-compassion and self-esteem. If self-compassion and self-esteem interact holistically within individuals (Fraser et al., 2023), we would expect to find groups of individuals who display the same levels of self-compassion and self-esteem regardless of whether these levels are high, moderate, or low. Conversely, if self-compassion and self-esteem operate separately, we could identify groups of individuals with different combinations of the levels of these constructs, such as those with high self-compassion and low self-esteem. Thus, identifying latent profiles can directly test Fraser et al.’s (2023) framework. Furthermore, this approach has practical implications. If the results support the interactive network of self-compassion and self-esteem within individuals, then interventions to boost self-compassion would also be effective in increasing self-esteem (Fraser et al., 2023). If these constructs operate separately, then the target of an intervention should be tailored to either self-compassion or self-esteem.

The present research aimed to identify how self-compassion and self-esteem operated within individuals by person-centered latent profile analyses. Based on the interactive network model of self-compassion and self-esteem (Fraser et al., 2023), we expected individuals to be classified into profiles characterized by high, moderate, or low levels of these constructs. We expected that few individuals would display a combination of high in one construct and low in another. Three studies examined these predictions to determine the stability and replicability of the obtained profiles.

We further investigated the profile differences in positive psychological functioning. Overall, individuals with high self-compassion and self-esteem were hypothesized to exhibit better intra-and interpersonal functioning than the groups of any other combination of self-compassion and self-esteem. This is because these individuals would feel worthy about themselves (Orth & Robins, 2022) and can regulate aversive experiences with compassion (Neff, 2011). Studies 1 and 2 focused on profile differences in intrapersonal functioning such as responses to negative events (Neff et al., 2021) and the satisfaction of basic psychological needs (Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2001). Study 3 examined these differences in social relationships (Lathren et al., 2021). Overall, the series of studies would provide a stable estimation of latent profiles and clarify profile differences in intra-and interpersonal functioning.

Study 1

Study 1 aimed to provide initial evidence of the latent patterns of self-compassion and self-esteem. We hypothesized that both self-compassion and self-esteem profiles would fall within a range of low to high levels, with some individuals exhibiting moderate levels of both traits. Furthermore, Study 1 examined profile differences in self-compassionate reactions (i.e., state self-compassion; Neff et al., 2021) and self-improvement orientations in response to a distressing event. Individuals with the combination of high self-compassion and self-esteem would display self-compassionate reactions to specific distress. To comprehensively assess self-improvement orientations, we used two indicators: negativity transformation (Mizuma, 2003) and openness to self-change (Chishima, 2016). The former is the inclination to change negative aspects of one’s personality (Mizuma, 2003), while the latter is a general tendency to be open to changing the self (Chishima, 2016). We expected individuals with a combination of high self-compassion and self-esteem to have higher negativity transformation and openness to self-change than those with the other profiles.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited through an Internet research company―Cross Marketing Inc. Of the 600 participants who agreed to participate, 57 did not describe painful experiences and 82 failed to respond correctly to an attention-check item. Thus, the final sample comprised 461 participants (222 men, 238 women, and one other). Their mean age was 44.3 years (SD = 13.9), ranging from 18 to 69 years. Their education attainment was as follows: 2.6% junior high school graduates, 26.0% high school graduates, 18.7% junior college or vocational school graduates/students, 47.3% university graduates/students, 5.2% post-graduates/students, and 0.2% other.

Measures

Self-compassion was assessed using the Japanese version of the Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form (SCS-SF; Arimitsu et al., 2016). This scale is composed of 12 items that represent CS and UCS. The Japanese SCS-SF was highly correlated with the Japanese version of the SCS (r = .95, Arimitsu et al., 2016). Participants were instructed to indicate the frequency with which they engaged in the behavior described by each item, concerning their experience of suffering on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). An example item is “I try to be understanding and patient towards those aspects of my personality I don’t like.” After reverse-coding the items that represented UCS, the mean scores of the 12 items were taken as self-compassion (α = .808).

Self-esteem was assessed using the Two-Item Self-Esteem Scale (TISE) developed by Minoura and Narita (2013). This scale comprises two items, “I feel that I have a number of good qualities” and “I feel good about myself.” This scale was highly correlated with the Japanese version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (r = .79; Minoura & Narita, 2013). Participants were instructed to indicate the extent to which each item described them on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). Two items were averaged to create self-esteem (α = .865).

Self-compassionate reactions were assessed using the State Self-Compassion Scale (SSCS; Neff et al., 2021). The Japanese version was translated and validated by Miyagawa et al. (2022). This scale consists of 18 items measuring self-compassionate reactions toward a distressing event. An example item is “I’m being supportive toward myself.” Participants indicated the extent to which each item described their current thoughts and feelings toward the recalled events on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). After reverse-coding nine items that represented state UCS, the mean scores of the 18 items were taken as state self-compassion (α = .890).

Negativity transformation was assessed using a scale to measure self-improvement orientation concerning one’s negative aspects (Mizuma, 2003). This scale comprises seven items, such as “I’m trying to figure out how to change my inadequacies.” Participants indicated the extent to which each item described their current thoughts on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). A mean score of these items was taken as negativity transformation (α = .932).

Openness to self-change was assessed using a scale developed by Chishima (2016). This scale contains three items such as “I’m interested in changing myself.” Participants indicated the extent to which each item described their current thoughts on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). These items were averaged to create openness to self-change (α = .904).Footnote 1

Procedure

Participants were instructed to recall and briefly describe their personal experiences that still caused pain (Neff et al., 2021). They then indicated how painful they felt at the moment (“I feel pain regarding this event”) on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree; M = 4.20, SD = 1.03). Subsequently, participants were asked to complete scales of self-compassionate reactions (Miyagawa et al., 2022; Neff et al., 2021), negativity transformation (Mizuma, 2003), and openness to self-change (Chishima, 2016) in response to their situation. Finally, participants were asked to respond to scales of trait self-compassion (Arimitsu et al., 2016) and self-esteem (Minoura & Narita, 2013). At the end of the questionnaire, participants were thanked for their participation.

Data analyses

We conducted latent profile analyses of self-compassion and self-esteem after standardizing them so that the scores were interpreted relative to the sample. These analyses were performed using Mplus version 8.7. To determine the number of profiles ranging from 1 to 5, we contrasted a model with its alternatives regarding model fit indices, parsimony, and interpretability (Ferguson et al., 2020). We evaluated model fit of plausible models based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and sample-adjusted Bayesian information criterion (SABIC). Lower values of these indices indicated a better fit (Marsh et al., 2004). Furthermore, we plotted and examined the change in these values; if the slopes of these values flattened, the model was considered better than the alternative models (Morin et al., 2016). The adjusted Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR; Lo et al., 2001) provided information on the best fit model regarding parsimony. The nonsignificant p value in the model with k + 1 profiles indicated that the model with k profiles was better (Lo et al., 2001).

Model fit indices should not be considered the golden standard for determining models (Marsh et al., 2005). Hence, when we identified plausible models based on these indices and the adjusted LMR test, we evaluated them in the following ways. First, we rejected a model with a profile containing less than 5% of participants (Ferguson et al., 2020). Second, we considered the interpretability of the obtained profiles (Ferguson et al., 2020). The model was adopted if adding a new profile to the model yielded a theoretically meaningful profile, such as a group with high self-compassion and low self-esteem. Conversely, if a model with k + 1 profiles did not provide such a meaningful group, we preferred a model with k profiles in terms of parsimony.

The Bolck–Croon–Hagenaars (BCH) method was conducted to examine the profile differences in the responses to negative events (i.e., state self-compassion, negativity transformation, and openness to self-change). The BCH method yields unbiased estimates of the profile means of distal outcomes by considering the measurement error of latent profiles (Bakk & Vermunt, 2016). Therefore, this method is more robust and performs better than other analyses such as ANOVAs using the obtained profiles (Bakk & Vermunt, 2016).

Results and brief discussion

Latent profiles of self-compassion and self-esteem

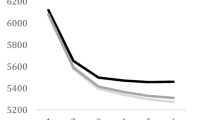

Table 1 displays the model fit indices, entropy, percentage of the smallest class, and adjusted LMR test. AIC, BIC, and SABIC showed better fit when the number of profiles increased. However, changes in these fit indices became relatively flat in the three-profile model (see supplementary online material Fig. S1). An adjusted LMR test supported the three-profile model as this test became nonsignificant in the four-profile model. The three-profile model included profiles of (1) low, (2) moderate, and (3) high self-compassion and self-esteem. Statistical analyses also supported the five-profile model: very low, low, moderate, high, and very high self-compassion and self-esteem. However, these five profiles did not comprise a new meaningful profile, such as the one with high self-compassion and low self-esteem. Therefore, we adopted the three-profile model for parsimony (Fig. 1). Entropy values indicated that 82.6% of participants were classified into their appropriate profiles.

Profile 1 described relatively low levels of self-compassion and self-esteem; hence we labeled this profile Low Compassionate and Worthy Style. This profile comprised 13.7% of participants (n = 63). Profile 2 was characterized by moderate levels of self-compassion and self-esteem, thus, labeled Moderate Compassionate and Worthy Style. This profile included 79.2% of participants (n = 365). Profile 3 showed relatively high levels of self-compassion and self-esteem. This profile, labeled High Compassionate and Worthy Style, comprised 7.2% of participants (n = 33). These profiles suggested that self-compassion and self-esteem were configured within individuals on a continuum from Low Compassionate and Worthy Style to High Compassionate and Worthy Style with Moderate Compassionate and Worthy Style in-between. The results indicated no combinations of (1) low self-compassion and high self-esteem and (2) high self-compassion and low self-esteem.

Profile differences in active responses to negative events

Table 2 illustrates the profile-specific means of the responses to negative events. The BCH method revealed significant profile differences in self-compassionate reactions, χ2(2) = 167.431, p < .001, negativity transformation, χ2(2) = 6.517, p < .001, and openness to self-change, χ2(2) = 12.553, p < .001. Individuals in High Compassionate and Worthy Style reported higher levels of self-compassionate reactions than those in Moderate and Low Compassionate and Worthy Styles (Table 2). These groups also differed in self-compassionate reactions in the expected direction. These results implied that when individuals related to themselves in a compassionate and worthy style, they were motivated to display self-compassionate reactions toward a distressing event.

Negativity transformation was higher in High Compassionate and Worthy Style than in Moderate Compassionate and Worthy Style. Notably, High Compassionate and Worthy Style did not significantly differ from Low Compassionate and Worthy Style. Thus, individuals with Low Compassionate and Worthy Style may also be motivated to improve their negative aspects as much as those with High Compassionate and Worthy Style did. However, the underlying motives for transforming negativity may differ between these two groups. Neff (2011, 2023) suggested that self-compassionate individuals accept themselves and initiate self-improvement when necessary because they care about themselves. Thus, negativity transformation displayed by individuals in High Compassionate and Worthy Style may illustrate positive and caring motives for their well-being. Conversely, individuals in Low Compassionate and Worthy Style may want to change their negative aspects because they cannot accept themselves and thus wish to become a different person. Cross-sectional research has shown that low self-esteem is positively associated with the inclination to change the whole aspects of the self (Chishima, 2014). Thus, negativity transformation of individuals with the low profile may reflect a rejection of the current self.

Indirect evidence of the different motives behind self-improvement appeared in how open individuals were to self-change. As shown in Table 2, openness to self-change was higher in High Compassionate and Worthy Style than in the other two groups which did not differ on this variable. Thus, individuals high in self-compassion and self-esteem were more open to initiating self-improvement than those low in these traits, partly because self-compassion and self-esteem offered a warm and positive attitude toward the self (Neff, 2011, 2023).

Overall, Study 1 provided initial support for the three-profile model of self-compassion and self-esteem. Furthermore, individuals with High Compassionate and Worthy Style displayed better intrapersonal functioning during a distressing event; they tended to show self-compassionate reactions and motivated themselves to change.

Study 2

In Study 2, we aimed to replicate the findings of the latent profiles of self-compassion and self-esteem. We expected that the same three-profile model was supported. We extended Study 1 by examining the profile differences in satisfaction with basic psychological needs (Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2001). According to the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2001), individuals have innate psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Individuals who are satisfied with these needs are likely to perform self-determined actions congruent with their inner values (Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2001). Fraser et al. (2023) posited that these individuals are also characterized by high self-compassion and self-esteem. Accordingly, it was expected that the groups with high self-compassion and self-esteem to be more satisfied with basic psychological needs than the other groups.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited through a crowdsourcing company in Japan (Lancers, Inc.). A total of 601 participants agreed to participate and completed questionnaires on Qualtrics. Data from ten participants were removed because they failed to respond correctly to one of the two attention-check items. The final sample comprised 591 participants (311 men and 280 women). Their mean age was 42.9 years (SD = 10.2), ranging from 20 to 75 years. Their education attainment was as follows: 1.7% junior high school graduates, 22.3% high school graduates, 20.4% junior college or vocational school graduates/students, 50.4% university graduates/students, 5.1% post-graduates/students, and 0.3% other.

Measures

Self-compassion was assessed using the Japanese SCS-SF (Arimitsu et al., 2016). Similar to Study 1, participants responded to this scale on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Self-compassion was created by calculating the mean score of 12 items after reverse-coding the UCS items (α = .876).

Self-esteem was assessed using the TISE (Minoura & Narita, 2013). Similar to Study 1, participants responded to this scale on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). The two items were averaged to create self-esteem (α = .840).

Basic psychological need satisfaction was assessed using the Basic Need Satisfaction in Life Scale (Ryan & Deci, 2000). The Japanese version was translated and validated by Okubo et al. (2013). This scale comprises 21 items and three subscales: needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Example items of these subscales are “I really like the people I interact with,” “Most days I feel a sense of accomplishment from what I do,” and “I have been able to learn interesting new skills recently.” Participants indicated the extent to which each scale item described themselves on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were satisfactory for autonomy (α = .712), competence (α = .778), and relatedness (α = .864). Thus, the mean score for each subscale represented satisfaction with needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, respectively.

Procedure

Participants were asked to respond to the scales of self-compassion (Arimitsu et al., 2016), self-esteem (Minoura & Narita, 2013), and basic psychological need satisfaction (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Okubo et al., 2003). They were thanked for their participation at the end of the questionnaire, participants. Additional measures were included for a separate paper on self-expression, which were not reported in this study.

Data analyses

We followed the data analyses described in Study 1. Specifically, we conducted latent profile analyses of standardized self-compassion and self-esteem. The number of profiles was determined based on model fit indices, parsimony, and interpretability (Ferguson et al., 2020). Next, the BCH method compared the profile-specific means of need satisfaction. Note that the descriptive statistics of the study variables can be found in Table S1.

Results and brief discussion

Latent profiles of self-compassion and self-esteem

As shown in Table 1, AIC, BIC, and SABIC improved as the number of profiles increased. Although these indicators and adjusted LMR tests suggested a five-profile model, this model did not include any combination of high self-compassion and low self-esteem, and vice versa. Similar to Study 1, this profile contained (1) very low, (2) low, (3) moderate, (4) high, and (5) very high self-compassion and self-esteem groups. Thus, we adopted a three-profile model as in Study 1 for interpretability and parsimony (Fig. 1). This model outperformed the two-and four-profile models, as evidenced by the flattening of the curve of model fit indices (see Supplementary Online Material Fig. S2). Entropy values indicated that 71% of participants were assigned to the appropriate groups.

The three groups were identical to those identified in Study 1. Profile 1, labeled Low Compassionate and Worthy Style, displayed relatively low scores for self-compassion and self-esteem. This profile included 17.8% of participants (n = 105). In Profile 2, the mean scores of self-compassion and self-esteem were at moderate levels; hence, this group was named Moderate Compassionate and Worthy Style, comprising 43.3% of participants (n = 256). Profile 3 was characterized by high levels of self-compassion and self-esteem. Thus, this profile was termed High Compassionate and Worthy Style, which contained 38.9% of participants (n = 230).

Profile differences in need satisfaction

As shown in Table 2, the BCH method indicated that the obtained profiles significantly differ in need satisfaction with autonomy, χ2(2) = 205.008, p < .001, competence, χ2(2) = 458.445, p < .001, and relatedness, χ2(2) = 188.051, p < .001. As expected, individuals with High Compassionate and Worthy Style reported higher satisfaction with autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs than the other groups (Table 2). Moderate Compassionate and Worthy Style also differed significantly from Low Compassionate and Worthy Style in the expected direction.

In summary, Study 2 provided further support for the three-profile model. Additionally, we found that individuals with High Compassionate and Worthy Style were the most satisfied with their basic psychological needs, which aligned with the findings from variable-centered approaches (Gunnell et al., 2017) and the theoretical framework (Fraser et al., 2023). Nonetheless, unlike the results of Study 1, the adjusted LMR and changes in model fit indices did not fully support the three-profile model. Thus, Study 3 examined whether this model was replicated within a larger sample.

Study 3

In Study 3, we aimed to replicate the three-profile model obtained in Studies 1 and 2. Furthermore, we extended Studies 1 and 2 by investigating the profile differences in interpersonal functioning in both general and intimate relationships. We assessed social isolation in general relationships and the quality of romantic relationships to comprehensively understand this association. Self-compassion and self-esteem tend to contribute to healthy relationships (Harris & Orth, 2020; Lathren et al., 2021; Orth & Robins, 2022). Both self-compassion and self-esteem were associated with lower levels of loneliness (Liu et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2013) and higher levels of relationship satisfaction (Erol & Orth, 2014; Neff & Beretvas, 2013). Furthermore, self-compassion was negatively associated with psychological intimate partner violence (IPV) perpetration toward romantic partners (Miyagawa & Kanemasa, 2023). Thus, we expected groups with high self-compassion and self-esteem to feel less socially isolated and maintain healthier romantic relationships than the other groups.

We used the datasets from an initial survey of a large longitudinal study on personality factors, social isolation, and IPV perpetration, the results of which will be reported elsewhere.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from an Internet research company―Cross Marketing, Inc. Participants were required to be involved in romantic relationships and under 40 years of age. A total of 3108 participants agreed to participate and completed this research. Among them, 584 participants failed to respond correctly to an attention check item. Hence, the final sample comprised 2524 participants (1228 men and 1296 women) involved in romantic relationships. Participants averaged 30.2 (SD = 5.8) years old, ranging from 18 to 39 years. Their education attainment was as follows: 2.5% junior high school graduates, 21.4% high school graduates, 19.1% junior college or vocational school graduates/students, 50.8% university graduates/students, and 6.2% post-graduates/students. The average duration of their current relationships was 38.59 (SD = 41.88) months. Most participants (80.0%) did not cohabit with their partners. Their partners averaged 30.8 (SD = 7.9) years old.

Measures

Self-compassion was assessed using the Japanese SCS-SF (Arimitsu et al., 2016). Participants responded on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Self-compassion was represented by a mean score of 12 items after reverse-coding the UCS items (α = .770).

Self-esteem was assessed using the TISE (Minoura & Narita, 2013). Participants responded on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). Self-esteem was taken as a mean score of the two items (α = .779).

Social isolation was assessed using two indicators to comprehensively understand this phenomenon: loneliness (Arimoto & Tadaka, 2019) and ostracized experiences (Rudert et al., 2020). Loneliness was measured using the Japanese version of the 10-item UCLA Loneliness Scale Version 3 (Arimoto & Tadaka, 2019). This scale has been validated in Japan (Arimoto & Tadaka, 2019) and contains ten items, such as “How often do you feel that you lack companionship?” Participants indicated how often they felt about the feelings and thoughts described by each item on a four-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). After reverse-coding the five items that indicated a lack of loneliness, a mean score of ten items was taken as loneliness (α = .858).

Ostracized experiences were assessed using the Ostracism Short Scale (Rudert et al., 2020). This scale comprises four items that measures the subjective frequency of feeling ostracized by others. An example item is “Others ignored me.” With permission from the original author, we translated the scale into Japanese using a back-translation procedure. The first and second authors translated the four items into Japanese. Next, a bilingual social psychologist back-translated them into English. Any inconsistencies were resolved through discussions. All three confirmed the equivalence between the original and Japanese items. Participants were instructed to rate how frequently they had experienced the situations described by each item during the past three months on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis with the weighted least squares mean- and variance-adjusted estimator to test the one-factor solution of the four items. Model fit indices showed excellent fit, CFA = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .057 [.035, .082]. The standardized factor loadings indicated that the one-factor solution was well-defined (λ = .918 to .967). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was adequate (α = .955). Therefore, we averaged the four items to indicate ostracized experiences.

Relationship satisfaction was assessed using the Relationship Satisfaction subscale of the Japanese version of the Investment Model Scale (Komura et al., 2013). The relationship satisfaction subscale comprises five items, including “I feel satisfied with our relationship.” Participants were instructed to indicate the extent to which each item described relationships with their partners on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all true for me) to 7 (very true for me). A mean score of these items represented relationship satisfaction (α = .946).

Psychological IPV perpetration and victimization were assessed using the Indirect and Psychological IPV Scale (Soma et al., 2004; Miyagawa & Kanemasa, 2023). This scale has been validated in Japan and contains six items each for perpetration and victimization. Participants indicated how frequently they had behaved toward their partners in a manner such as “Restricted their partner’s behavior” (i.e., psychological IPV perpetration) and their partner had done so (psychological IPV victimization) during the past three months. Participants rated these items on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). We calculated mean scores for psychological IPV perpetration and victimization (αs = .898 and .897, respectively).

Procedure

After completing the scales of self-compassion and self-esteem (Arimitsu et al., 2016; Minoura & Narita, 2013), participants indicated the degree to which they felt isolated from others by responding to measures of loneliness (Arimoto & Tadaka, 2019) and ostracized experiences (Rudert et al., 2020). Subsequently, participants were instructed to think of their current romantic partners, provide demographic information about their romantic relationships, and complete the scales of relationship satisfaction (Komura et al., 2013) and the frequencies of psychological IPV perpetration and victimization (Soma et al., 2004; Miyagawa & Kanemasa, 2023). At the end of the survey, participants were thanked for their participation.

Data analyses

We followed the analytical procedures described in Studies 1 and 2. We performed latent profile analyses of standardized self-compassion and self-esteem. Subsequently, we conducted the BCH method to compare the levels of interpersonal functioning obtained by participants displaying different latent profiles. Note that the descriptive statistics of the study variables can be found in Table S1.

Results and brief discussion

Latent profiles of self-compassion and self-esteem

As in Studies 1 and 2, AIC, BIC, and SABIC values decreased as the number of profiles increased (Table 1). The curve of these values was moderate in a three-profile model (supplementary online material Fig. S3). Although adjusted LMR was significant in a five-profile model, the smallest class was below 5%; therefore, it was rejected. We adopted the three-profile model for statistical evidence, parsimony, and interpretability (Fig. 1).

Profile 1 included 10.4% of participants (n = 263) who displayed low levels of self-compassion and self-esteem. As in Studies 1 and 2, we labeled this profile Low Compassionate and Worthy Style. Profile 2 contained 82.3% of participants (n = 2078) who showed moderate levels of self-compassion and self-esteem. This profile was labeled Moderate Compassionate and Worthy Style. Profile 3 comprised 7.3% of participants (n = 183) with high levels of self-compassion and self-esteem. Hence, we termed this group High Compassionate and Worthy Style.

Profiles differences in interpersonal functioning

The BCH method suggested profile-specific mean differences in loneliness, χ2(2) = 506.446, p < .001, ostracized experiences, χ2(2) = 272.388, p < .001, relationship satisfaction, χ2(2) = 175.505, p < .001, psychological IPV perpetration, χ2(2) = 43.410, p < .001, and psychological IPV victimization, χ2(2) = 83.996, p < .001. Overall, subsequent post-hoc comparisons revealed profile differences in these variables in the expected direction (Table 2).

Individuals with High Compassionate and Worthy Style reported lower levels of loneliness and fewer ostracized experiences from others than those with the moderate and low styles, the latter of which differed significantly in these variables. Thus, individuals high in self-compassion and self-esteem tended to feel less socially isolated from others. This may be because they have a positive attitude toward themselves (Orth & Robins, 2022) and are good at regulating negative affect (Neff, 2011, 2023).

Individuals with High Compassionate and Worthy Style reported higher levels of relationship satisfaction and lower frequencies of psychological IPV perpetration and victimization in romantic relationships than individuals with the other profiles.Footnote 2 Individuals with high self-compassion and self-esteem may cope well with relationship issues well and, thus, maintain good relationships with others (Lathren et al., 2021; Neff & Beretvas, 2013).

Overall, Study 3 provided evidence of the three-profile model of self-compassion and self-esteem. Additionally, we found that individuals with High Compassionate and Worthy Style tended to feel less lonely and ostracized in general relationships and maintain satisfied, nonviolent romantic relationships than those with the other profiles. These results attested to positive interpersonal functioning displayed by individuals with high self-compassion and self-esteem.

General discussion

This research aimed to identify the latent profiles of self-compassion and self-esteem and clarify profile differences in intra-and interpersonal functioning such as responses to negative events in Study 1, satisfaction with basic psychological needs in Study 2, and quality of interpersonal relationships in Study 3. Across the three studies, individuals were classified into three latent profiles: Low Compassionate and Worthy Style (low self-compassion and self-esteem), Moderate Compassionate and Worthy Style (moderate self-compassion and self-esteem), and High Compassionate and Worthy Style (high self-compassion and self-esteem). We did not identify any profiles displaying high self-compassion and low self-esteem simultaneously, or vice versa. These results converged with the interactive network model of self-compassion and self-esteem (Fraser et al., 2023) and suggested that self-compassion and self-esteem would operate in a unified rather than separated manner within individuals. Therefore, if one retains high self-compassion, this person is likely to hold high self-esteem.

The profile differences in intrapersonal functioning were consistent with our predictions. Overall, individuals with High Compassionate and Worthy Style were more likely to display self-compassionate reactions and self-improvement orientations during negative events and feel satisfied with their basic psychological needs for relatedness, autonomy, and competence. These findings suggest that individuals with High Compassionate and Worthy Style tend to meet their psychological needs, and protect and enhance their well-being in times of distress, presumably because they have positive regard toward the self (Orth & Robins, 2022) and care about themselves (Neff, 2011, 2023).

As predicted, the obtained profiles differed in interpersonal functioning. Compared to those in the other groups, individuals with High Compassionate and Worthy Style felt less lonely and experienced less ostracization. They also reported higher satisfaction with romantic relationships and lower experiences of violence in romantic relationships. Their positive and compassionate attitudes toward themselves (Neff, 2011, 2023; Orth & Robins, 2022) may spill over to their relationships with others and romantic partners.

These profile differences align with the findings of variable-centered approaches (e.g., Orth & Robins, 2022; Neff & Vonk, 2009; Zhang & Chen, 2016). These approaches found that both self-compassion and self-esteem were associated with positive intra-and interpersonal functioning such as satisfaction with basic psychological needs (Gunnell et al., 2017), self-improvement (Zhang & Chen, 2016), and low levels of loneliness (Liu et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2013). Importantly, our results do not contradict previous findings of these variable-centered approaches. Rather, combined with them, the current findings contributed to an understanding of how self-compassion and self-esteem operated within individuals and how these traits promoted positive psychological functioning. We found that individuals could be classified into three groups with different functional characteristics. For instance, while individuals in High Compassionate and Worthy Style motivated themselves to change, this may be driven by self-compassion rather than self-esteem; Zhang and Chen (2016) found that self-compassion, rather than self-esteem, was a stronger predictor of self-improvement orientations. Furthermore, for individuals with High Compassionate and Worthy Style, self-esteem may become a foundation for self-compassion that promotes self-improvement (Donald et al., 2018). Overall, person-centered approaches can identify possible intra-individual combinations (i.e., latent profiles) of self-compassion and self-esteem, the size of each profile, and profile differences in psychological functioning, whereas variable-centered approaches can clarify how self-compassion and self-esteem uniquely influence psychological functioning (Ferguson et al., 2020; Keefer et al., 2012; Spurk et al., 2020). These approaches illustrate that self-compassion and self-esteem are likely to form an interactive network within individuals (Fraser et al., 2023) and that these traits may uniquely or independently facilitate positive intra-and interpersonal functioning.

Research on self-compassion have conducted latent profile analyses to identify the latent profiles of the six elements of self-compassion and to examine whether these profiles converge with the conceptualization of self-compassion (Phillips, 2021; Miyagawa & Neff, 2023). Overall, studies have identified three profiles (i.e., high CS and low UCS, moderate CS and UCS, and low CS and high UCS) that support the argument that CS and UCS work holistically to create a self-compassionate mind (Phillips, 2021; Miyagawa & Neff, 2023). Our research extended the understanding of the configuration of self-compassion in a novel manner: latent profile analyses to examine the combination of self-compassion and self-esteem. Similar to the subcomponents of self-compassion (Phillips, 2021; Miyagawa & Neff, 2023), our results indicated that self-compassion and self-esteem operated in tandem to support psychological functioning. As an interesting future direction, subsequent research using latent profile analyses examines and describes how self-compassion works with or separately from other constructs within individuals.

Our study had several limitations regarding the methodology; thus, caution should be exercised when interpreting the findings. First, we assessed self-compassion and self-esteem using short-form scales (Arimitsu et al., 2016; Minoura & Narita, 2013). Although these scales have been validated and shown strong correlation with the long-forms (Arimitsu et al., 2016; Minoura & Narita, 2013), future studies should replicate our results by using the long-forms to assess these constructs comprehensively. Second, there appeared to be heterogeneity in the sizes of the obtained profiles among the three studies. The percentage of individuals with High Compassionate Style and Worthy was higher in Study 2 than in Studies 1 and 3. This may be influenced by potential differences in sample characteristics or recruitment methods, which future studies should examine. Despite heterogeneity in the size of the profiles, across the three studies, we did not identify a group of individuals displaying high levels of one trait and low levels of another. Thus, we considered that self-compassion was in tandem with self-esteem within individuals, regardless of the samples. Finally, we collected data from Japan and, thus, cross-cultural validation of the obtained profiles is required. Self-compassion is known to work holistically in the U.S. and Japan (Miyagawa & Neff, 2023). Furthermore, self-compassion was related to well-being across Western and Eastern cultures (Gunnell et al., 2017; Pandey et al., 2021; Tiwari et al., 2020). Therefore, we would expect similar profiles of self-compassion and self-esteem to be identified across diverse cultures. Future cross-cultural studies should directly test this hypothesis.

In summary, we proposed that individuals can be classified into three Compassionate and Worthy Styles. Our results indicated that self-compassion and self-esteem were two important aspects of the self-concept that operated in a united manner within individuals to facilitate positive intra-and interpersonal functioning. Future research could expand our findings by examining profile differences in other important psychological functions such as maintaining mental and physical health, regulating emotions, and employing coping strategies. Furthermore, given the interactive network of self-compassion and self-esteem (Fraser et al., 2023), our results imply that interventions to increase self-compassion may also promote self-esteem. Interventions to boost self-esteem is promising (Orth & Robins, 2022). Still, these interventions might also have side effects for some individuals because excessive concerns about pursing self-esteem often orient individuals to become self-defensive and avoid learning from failures (Crocker & Park, 2012). Conversely, theory and research suggest that self-compassion interventions help individuals accept their personal inadequacies, failures, and negative events and make the necessary changes (Miyagawa & Neff, 2023; Neff, 2023; Zhang & Chen, 2016). These self-compassion interventions could increase feelings of self-worth without the individuals becoming self-defensive. In other words, if individuals develop self-compassionate mind, they may come to feel worthy as a person. Future research could benefit from examining whether a transition in profile memberships occurs after interventions to cultivate self-compassion. The aforementioned future directions could provide further evidence for the interactive network model of self-compassion and self-esteem (Fraser et al., 2023) and for the psychological benefits of being high in self-compassion and self-esteem (Neff, 2023; Orth & Robins, 2022).

Data availability

The datasets for this study are freely available at https://osf.io/a6puw/.

Notes

Please see Supplementary Online Material Table S1 for the mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis of study variables.

Psychological IPV perpetration and victimization were leptokurtic and positively skewed (Table S1), which could affect the results of the mean differences between the obtained profiles. To rule out this possibility, we also used the base 10 log-transformed variables when examining profile differences in psychological IPV. Importantly, the results of the additional analyses were identical to the main findings. The BCH method suggested profile-specific mean differences in log-transformed psychological IPV perpetration, χ2(2) = 63.454, p < .001, and log-transformed psychological IPV victimization, χ2(2) = 68.868, p < .001. Individuals with High Worthy and Compassionate Style were lower in psychological IPV perpetration and victimization than those with the other profiles. We did not find significant differences between the low and moderate groups in psychological IPV perpetration and victimization (see Supplementary Online Material Table S2).

References

Arimitsu, K., Aoki, Y., Furukita, M., Tada, A., & Togashi, R. (2016). Construction and validation of a short form of the Japanese version of the self-compassion scale. Komazawa Annual Reports of Psychology, 18, 1–9. http://repo.komazawa-u.ac.jp/opac/repository/all/35874/

Arimoto, A., & Tadaka, E. (2019). Reliability and validity of Japanese versions of the UCLA loneliness scale version 3 for use among mothers with infants and toddlers: A cross-sectional study. BMC Women's Health, 19, 105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-019-0792-4

Bakk, Z., & Vermunt, J. K. (2016). Robustness of stepwise latent class modeling with continuous distal outcomes. Structural Equation Modeling, 23(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.955104

Chishima, Y. (2014). Aspects of intention for self-change in university students: Focusing on the relations with personality development and psychological adjustment. The Japanese Journal of Adolescent Psychology, 25(2), 85–103. https://doi.org/10.20688/jsyap.25.2_85

Chishima, Y. (2016). Intention for self-change across the life span: Focusing on concern about self-change. The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 87(2), 155–164. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.87.15201

Crocker, J., & Park, L. E. (2012). Contingencies of self-worth. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 309–326). The Guilford Press.

Donald, J. N., Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P. D., Sahdra, B. K., Marshall, S. L., & Guo, J. (2018). A worthy self is a caring self: Examining the developmental relations between self-esteem and self-compassion in adolescents. Journal of Personality, 86, 619–630. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12340

Erol, R. Y., & Orth, U. (2014). Development of self-esteem and relationship satisfaction in couples: Two longitudinal studies. Developmental Psychology, 50(9), 2291–2303. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037370

Ferguson, S. L., Moore, G., & E. W., & Hull, D. M. (2020). Finding latent groups in observed data: A primer on latent profile analysis in Mplus for applied researchers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(5), 458–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419881721

Fraser, M. I., Ciarrochi, J., Sahdra, B. K., & Hunt, C. (2023). To be compassionate and feel worthy : The bidirectional relationship between self-compassion and self-esteem. In A. Finlay-Jones et al. (Eds.), Handbook of self-compassion (pp. 33–51). Springer.

Gunnell, K. E., Mosewich, A. D., McEwen, C. E., Eklund, R. C., & Crocker, P. R. E. (2017). Don't be so hard on yourself! Changes in self-compassion during the first year of university are associated with changes in well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 107, 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.11.032

Harris, M. A., & Orth, U. (2020). The link between self-esteem and social relationships: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(6), 1459–1477. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000265

Keefer, K. V., Parker, J. D. A., & Wood, L. M. (2012). Trait emotional intelligence and university graduation outcomes: Using latent profile analysis to identify students at risk for degree noncompletion. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 30(4), 402–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282912449446

Komura, K., Nakamine, M., & Matsui, Y. (2013). Development of a Japanese version of the investment model scale and an examination of its reliability and validity. Tsukuba Psychological Research, 46, 39–47. https://tsukuba.repo.nii.ac.jp/records/29603

Krieger, T., Hermann, H., Zimmermann, J., & grosse Holtforth, M. (2015). Associations of self-compassion and global self-esteem with positive and negative affect and stress reactivity in daily life: Findings from a smart phone study. Personality and Individual Differences, 87, 288–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.009

Lathren, C. R., Rao, S. S., Park, J., & Bluth, K. (2021). Self-compassion and current close interpersonal relationships: A scoping literature review. Mindfulness, 12(5), 1078–1093. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01566-5

Liu, X., Yang, Y., Wu, H., Kong, X., & Cui, L. (2022). The roles of fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety in the relationship between self-compassion and loneliness: A serial mediation model. Current Psychology, 41(8), 5249–5257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01001-x

Lo, Y., Mendell, N. R., & Rubin, D. B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88(3), 767–778. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/88.3.767

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., & Wen, Z. (2004). In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler's (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling, 11(3), 320–341. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., & Grayson, D. (2005). Goodness of fit in structural equation models. In A. Maydeu-Olivares & J. J. McArdle (Eds.), Contemporary psychometrics: A Festschrift for Roderick P. McDonald (pp. 275–340). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Minoura, K., & Narita, Y. (2013). The development of the two-item self-esteem scale (TISE): Reliability and validity. Japanese Journal of Research on Emotions, 21, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.4092/jsre.21.37

Miyagawa, Y., & Kanemasa, Y. (2023). perpetration: Low self-compassion and compassionate goals as mediators. Journal of Family Violence, 38, 1443–1455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00436-z

Miyagawa, Y., & Neff, K. D. (2023). How self-compassion operates within individuals: An examination of latent profiles of state self-compassion in the U.S. and Japan. Mindfulness, 14(6), 1371–1382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02143-2

Miyagawa, Y., Tóth-Király, I., Knox, M. C., Taniguchi, J., & Niiya, Y. (2022). Development of the Japanese version of the state self-compassion scale (SSCS-J). Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 779318. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.779318

Mizuma, R. (2003). Feelings of self-disgust and self-development: The intention to change the negative self. The Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology, 51(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.5926/jjep1953.51.1_43

Morin, A. J. S., Meyer, J. P., Creusier, J., & Biétry, F. (2016). Multiple-group analysis of similarity in latent profile solutions. Organizational Research Methods, 19(2), 231–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428115621148

Neff, K. D. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x

Neff, K. D. (2023). Self-compassion: Theory, method, research, and intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 74, 193–218. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-032420-031047

Neff, K. D., & Beretvas, S. N. (2013). The role of self-compassion in romantic relationships. Self and Identity, 12(1), 78–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2011.639548

Neff, K. D., & Vonk, R. (2009). Self-compassion versus global self-esteem: Two different ways of relating to oneself. Journal of Personality, 77(1), 23–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00537.x

Neff, K. D., Tóth-Király, I., Knox, M. C., Kuchar, A., & Davidson, O. (2021). The development and validation of the state self-compassion scale (long- and short form). Mindfulness, 12(1), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01505-4

Okubo, T., Naganuma, N., & Aoyagi, H. (2003). The relationship between psychological need satisfaction and subjective adjustment in school environment. Human Science Research, 12, 21–28 http://hdl.handle.net/2065/33920

Orth, U., & Robins, R. W. (2022). Is high self-esteem beneficial? Revisiting a classic question. American Psychologist, 77(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000922

Pandey, R., Tiwari, G. K., Parihar, P., & Rai, P. K. (2021). Positive, not negative, self-compassion mediates the relationship between self-esteem and well-being. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 94(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12259

Phillips, W. J. (2021). Self-compassion mindsets: The components of the self-compassion scale operate as a balanced system within individuals. Current Psychology, 40(10), 5040–5053. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00452-1

Rudert, S. C., Keller, M. D., Hales, A. H., Walker, M., & Greifeneder, R. (2020). Who gets ostracized? A personality perspective on risk and protective factors of ostracism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(6), 1247–1268. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000271

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Soma, T., Ura, M., Ochiai, A., & Fukazawa, Y. (2004). Prevention of violence by romantic partners as a function of interpersonal relationships: As a function of cooperative and uncooperative orientation in a romantic relationship and social support outside the relationship. Behavioral Science Research, 43(1), 1–7 https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1520290884276665344

Spurk, D., Hirschi, A., Wang, M., Valero, D., & Kauffeld, S. (2020). Latent profile analysis: A review and “how to” guide of its application within vocational behavior research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 120, 103445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103445

Tiwari, G. K., Pandey, R., Rai, P. K., Pandey, R., Verma, Y., Parihar, P., Ahirwar, G., Tiwari, A. S., & Mandal, S. P. (2020). Self-compassion as an intrapersonal resource of perceived positive mental health outcomes: A thematic analysis. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 23(7), 550–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2020.1774524

Zhang, J. W., & Chen, S. (2016). Self-compassion promotes personal improvement from regret experiences via acceptance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(2), 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215623271

Zhao, J., Kong, F., & Wang, Y. (2013). The role of social support and self-esteem in the relationship between shyness and loneliness. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(5), 577–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.003

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Selma C Rudert for her permission to translate the Ostracism Short Scale and Dr. Yu Niiya for her assistance with the back-translation of the scale. Our work was funded by JSPS KAKENHI grant (JP20K14147) and JSPS KAKENHI grant (JP18H01080).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuki Miyagawa: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing-Original Draft, Resources, Funding acquisition. Yuji Kanemasa: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Review & Editing, Resources, Funding acquisition. Junichi Taniguchi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This research has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of the affiliated universities of the first and second authors. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with any of the findings published in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 267 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Miyagawa, Y., Kanemasa, Y. & Taniguchi, J. A compassionate and worthy self: latent profiles of self-compassion and self-esteem in relation to intrapersonal and interpersonal functioning. Curr Psychol 43, 14259–14272 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05428-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05428-w