Abstract

Prostaglandins (PGs) are signaling lipids derived from arachidonic acid (AA), which is metabolized by cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 or 2 and class-specific synthases to generate PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, PGI2 (prostacyclin), and thromboxane A2. PGs signal through G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and are important modulators of an array of physiological functions, including systemic inflammation and insulin secretion from pancreatic islets. The role of PGs in β-cell function has been an active area of interest, beginning in the 1970s. Early studies demonstrated that PGE2 inhibits glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS), although more recent studies have questioned this inhibitory action of PGE2. The PGE2 receptor EP3 and one of the G-proteins that couples to EP3, GαZ, have been identified as negative regulators of β-cell proliferation and survival. Conversely, PGI2 and its receptor, IP, play a positive role in the β-cell by enhancing GSIS and preserving β-cell mass in response to the β-cell toxin streptozotocin (STZ). In comparison to PGE2 and PGI2, little is known about the function of the remaining PGs within islets. In this review, we discuss the roles of PGs, particularly PGE2 and PGI2, PG receptors, and downstream signaling events that alter β-cell function and regulation of β-cell mass.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Diabetes is a major healthcare concern in the United States, affecting more than 9% of the population (Center for Disease Control, National Statistics Report 2014). Among those with diabetes, 90–95% are diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes (T2D). In the face of increased metabolic demand, such as obesity-related insulin resistance, the insulin producing β-cells of the pancreatic islets normally increase insulin output and expand functional β-cell mass to compensate for this metabolic stress (Golson et al. 2010). However, this β-cell plasticity is lost in the setting of T2D in humans and rodents (Sachdeva and Stoffers 2009). Pancreatic β-cell failure, in combination with peripheral insulin resistance, ultimately results in T2D. The incidence of T2D increases with age, with 26% of individuals over the age of 65 affected by T2D (Center for Disease Control, National Statistics Report 2014). The increased prevalence of T2D with age is multifaceted. In the β-cell, a combination of increased expression of cell cycle inhibitors and decreased capability to respond to proliferative cues with age likely contributes to the increase in disease incidence (Gunasekaran and Gannon 2011). Understanding the signaling mechanisms that drive β-cell proliferation and the islet changes that occur with age will have important implications on therapeutics intended to enhance functional β-cell mass in patients with T2D.

Obesity-associated T2D is characterized by hyperglycemia and chronic low-grade inflammation, resulting in increased circulating cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) (Sjoholm and Nystrom 2006). Eicosanoids, biologically active metabolites of the membrane lipid arachidonic acid (AA), play important roles in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and T2D (Luo and Wang 2011). AA is metabolized into eicosanoids by three major pathways, which include the activity of cyclooxygenase (COX), lipoxygenase (LOX), and cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes. The roles of LOX- and CYP-derived eicosanoids in β-cells are outside of the scope of this review, but we refer the reader to a previously published review on this topic (Luo and Wang 2011). The COX-derived eicosanoids, called prostaglandins (PGs), are important lipid signaling molecules that mediate an array of physiological functions, including inflammation and positively or negatively regulate insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells (Hata and Breyer 2004; Robertson 1988). PGs are produced in a multi-step process (Fig. 1). The first step involves release of AA from plasma membrane phospholipids by the action of phospholipase A2 (PLA2), which recognizes and hydrolyzes sn-2 acyl bonds of phospholipids, releasing AA. This is the rate-limiting step in PG synthesis (Samad et al. 2001). The next steps in PG synthesis require the activity of the constitutively active COX-1 or the inducible COX-2. It has been demonstrated that COX-2 is predominantly expressed in islets (Sorli et al. 1998; Tran et al. 1999). AA is first oxidized by COX-1 or −2 to generate PGG2, and then undergoes reduction by COX-1 or −2 forming the unstable metabolite PGH2. The final step in PG synthesis involves the activity of PG synthases on PGH2 to form the five main PG family members: PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, PGI2 (prostacyclin), and TXA2 (thromboxane). These signaling molecules exert their action on the cell by signaling through their respective G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) called DP1 and DP2 (also known as CRTH2), EP1–4, FP, IP, and TP (Hata and Breyer 2004). GPCRs represent 50–60% of current drug targets (Lundstrom 2009), highlighting the potential of these receptors as future druggable targets for the treatment of T2D. Indeed, many GPCRs expressed in islets have been studied in terms of their ability to regulate β-cell function and/or mass (reviewed in (Ahren 2009)).

Prostaglandin Synthesis. Arachidonic acid is released from plasma membrane phospholipids by the action of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and is then metabolized by cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 or −2 to the unstable metabolite PGH2, which serves as the precursor for the five main prostaglandin (PG) members. Activity of specific synthases for each individual PG (PGDS, PGES, PGFS, PGIS, or TxAS) leads to generation of the five principle PGs: PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, PGI2, and Thromboxane (TX) A2. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) block the activity of COX-1 and -2

PGs have long been implicated in diabetes, dating back to the 1800s. In 1876, Ebstein noted that the anti-inflammatory drug sodium salicylate, which inhibits COX activity, reduced the amount of glucose present in urine samples from patients with diabetes (Ebstein 1876; Robertson 1988). Historically, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that inhibit COX-2 activity, such as aspirin and sodium salicylate, were used to treat diabetes (Robertson 1983). In 1974, nearly 100 years after Ebstein’s observations, Burr and Sharp demonstrated that PGE1 inhibited glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) by perifusion assay in rat islets (Burr and Sharp 1974), thus providing a potential explanation for Ebstein’s early observations. Increased levels of mRNA and proteins associated with PG production have also been associated with T2D. The expression of Ptgs2 (COX-2) can be increased by several different means: 1. by IL-1β treatment in the RIN 832/13 β-cell line (Burke and Collier 2011), and rodent and human islets (Heitmeier et al. 2004; Parazzoli et al. 2012; Sorli et al. 1998); 2. in islets from the T2D db/db mouse model (Shanmugam et al. 2006); and 3. by hyperglycemia in rodent and human islets (Persaud et al. 2004; Shanmugam et al. 2006). Similarly, PGE2 production is induced by IL-1β and hyperglycemia in β-cells (Heitmeier et al. 2004; Shanmugam et al. 2006; Tadayyon et al. 1990; Tran et al. 1999) and is increased in T2D mouse and human islets (Kimple et al. 2013). These data unveil an interesting link between obesity, T2D, and PG signaling.

This review will focus on the role of PGs, their receptors, and their impact on β-cell function and regulation of β-cell mass. To our knowledge, there is no evidence of TXA2 in regulating either β-cell function or mass; therefore, we focus on the remaining PG family members in this article.

PGs and β-cell function

Proper regulation of insulin secretion from β-cells is critical for maintaining euglycemia. Insulin secretion is stimulated by elevated glucose and follows a biphasic secretion pattern. The initial peak in GSIS occurs minutes after stimulation as a result of the triggering pathway, and is followed by a lower, sustained level of secretion as a product of the amplifying pathway (recently reviewed in (Wortham and Sander 2016)). During the triggering pathway, glucose is metabolized via glycolysis and the mitochondrial TCA cycle, increasing the ATP/ADP ratio, leading to closure of the ATP-sensitive KATP channels and subsequent membrane depolarization. Following depolarization, voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels open, causing an influx of Ca2+ and stimulation of insulin granule exocytosis (Fig. 2). The amplifying pathway potentiates the effects of the triggering pathway and integrates different metabolic cues, such as free fatty acids, together with endocrine and neuronal signals to adjust insulin secretion as necessary (Wortham and Sander 2016). As mentioned in the introduction, COX-2, as well as COX-derived PGs, have been implicated in the regulation of β-cell function. Interestingly, two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the PTGS2 (COX-2) gene have been associated with T2D risk in Pima Indians (Konheim and Wolford 2003), suggesting that COX-2 may play a role in the onset of T2D by increasing PG production.

Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion pathway. Glucose enters the β-cell via GLUT2 (mouse) or GLUT1 (human) where it is phosphorylated to glucose-6-phosphate by glucokinase. Glucose-6-phosphate is metabolized in the mitochondria, generating ATP. An increase in the ATP/ADP ratio leads to closure of KATP channels, membrane depolarization, and subsequent opening of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. Increased cytosolic Ca2+ levels triggers insulin granule release. ATP can also lead to formation of cAMP. cAMP signals via protein kinase A (PKA) or exchange factor directly activated by cAMP (Epac) 2 and can amplify insulin secretion. Hollow block arrows represent components also regulated by PGs that may be involved in altering insulin release

Studies using radiolabeled AA demonstrated that PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, and PGI2 are all produced in rat islets (Evans et al. 1983; Kelly and Laychock 1981, 1984). Subsequent work by Vennemann and colleagues confirmed that these PG products are synthesized in mouse pancreata and demonstrated that production increases following treatment with streptozotocin (STZ), a β-cell toxin (Vennemann et al. 2012). This group also revealed that PGE2 is the main PG produced in mouse pancreatic tissue (Vennemann et al. 2012). In addition to being induced by STZ, PGE2 and PGI2 production are increased in islets by high glucose culture conditions (Gurgul-Convey et al. 2012; Persaud et al. 2004; Shanmugam et al. 2006). PGs have very short half-lives and thus act locally in an autocrine or juxtacrine manner to signal through their respective receptors (Hata and Breyer 2004; Tootle 2013).

The receptors for each of the PGs are expressed in immortalized β-cell lines, rodent islets, and human islets. PGD2 binds and signals through two different receptors called DP1 and DP2 [also known as Prostaglandin D2 Receptor 2 (PTGDR2), chemoattractant receptor-homologous expressed on Th2 lymphocytes receptor (CRTH2), CD294, or GPR44] (Hata and Breyer 2004; Hellstrom-Lindahl et al. 2016). DP1 and DP2 are expressed in islets and DP2 (GPR44) has endocrine-specific expression in human tissues (Bramswig et al. 2013; Hellstrom-Lindahl et al. 2016; Lindskog et al. 2012). The DP1 receptor couples to the stimulatory G protein (GS) leading to increases in intracellular cAMP, whereas the DP2 receptor couples to the inhibitory G protein (Gi) decreasing intracellular cAMP (Hata and Breyer 2004). PGE2 signals through four receptors called EP1–4. EP1 couples to Gq, resulting in increases in intracellular Ca2+ levels. EP2 and EP4 couple to GS whereas EP3 primarily couples to the Gi subfamily proteins, which is composed of Gi1, Gi2, Gi3, Go1, Go2 and GZ (Hata and Breyer 2004; Kimple et al. 2014). PGE2 binds with highest and equal affinity to EP3 and EP4 and lower affinity to EP1 and EP2 (Abramovitz et al. 2000). The PGE2 synthase genes (Ptges1–3) as well as the receptor genes (Ptger1–4) are all expressed in both mouse and human islets (Bramswig et al. 2013; Kimple et al. 2013; Ku et al. 2012; Tran et al. 1999; Vennemann et al. 2012). However, recent RNA-sequencing failed to detect the expression of Ptger2 (EP2) in mouse islets (Ku et al. 2012); thus further research is needed to clarify these discrepancies. PGF2α binds to the FP receptor, which signals through the Gq protein resulting in a rise in intracellular Ca2+ levels (Hata and Breyer 2004). RNA-sequencing reveals that the FP receptor gene (PTGFR) is expressed in human islets (Bramswig et al. 2013). PGI2, also known as prostacyclin, signals through the IP receptor which primarily couples to GS (Hata and Breyer 2004). Expression of the PGI2 synthase PGIS (Ptgis) and IP has been detected in β-cell lines, rat islets, and human islets (Bramswig et al. 2013; Gurgul-Convey and Lenzen 2010). The TXA2 receptor TP (TBXA2R) and synthase (TBXAS1) are expressed in human islets (Bramswig et al. 2013), yet there is no known role of TXA2 in either β-cell function or mass dynamics.

Based on the primary signaling mechanisms of the PG receptors (cAMP, Ca2+), and the known mechanisms regulating GSIS (Figure 2), one might predict that PGs would function in regulation of insulin secretion. To our knowledge, there are no reports implicating a role for either PGD2 or PGF2α in GSIS. One group found that PGD2 administration promoted glucagon secretion, but had no impact on insulin secretion (Akpan et al. 1979). Therefore, in this section we will discuss what is known about PGI2, PGE2, and their respective receptors in terms of β-cell function.

PGI2 and β-cell function

Early studies in the late 1970s and 1980s suggested that PGI2 plays little to no role in altering GSIS. In perfused rat pancreata, PGI2 did not affect insulin or glucagon secretion (Akpan et al. 1979). Similarly, in healthy human males, a two-hour PGI2 infusion, at a dose sufficient to cause changes in platelets and vasculature, did not alter GSIS or glucose disposal during the course of the study (Patrono et al. 1981). A shorter PGI2 infusion of 48 h in patients with T2D that were being treated for vascular disease resulted in a hyperglycemic effect but did not impact plasma insulin levels in response to glucose (Szczeklik et al. 1980). However, in non-diabetic participants, the results were variable with PGI2 infusion decreasing, increasing, or not affecting GSIS (Szczeklik et al. 1980). To further investigate the hyperglycemic effect observed in patients with T2D, Sieradzki and colleagues performed GSIS studies in isolated rat islets using low, medium, and high concentrations of PGI2 (Sieradzki et al. 1984). The low concentration of PGI2 (2.7 nM) had no effect on GSIS in low or high glucose. The mid-range dose of PGI2 (53.8 nM) initially stimulated but then decreased GSIS in high glucose conditions. The highest dose of PGI2 (267 nM) resulted in inhibition of GSIS. These results suggest that there is a dose-dependent effect of PGI2 on insulin release in isolated islets. Alternatively, it is possible that PGI2 has off target effects when used at high concentrations.

More recently, PGI2 has been shown to play a positive role in stimulating insulin release in β-cell lines. Interestingly, high glucose increases the expression of Ptgis and PGIS in rat islets suggesting that PGI2 has a role in GSIS (Gurgul-Convey et al. 2012). Overexpression of PGIS in the rat INS-1E β-cell line enhances GSIS during high glucose stimulation, but does not have an effect under substimulatory glucose conditions. The IP agonist iloprost also increased GSIS in INS-1E cells while the PGI2 antagonist CAY10441 decreased insulin release in PGIS-overexpressing cells (Gurgul-Convey et al. 2012). The mechanism underlying this PGIS-potentiated GSIS was not due to signaling via the cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) pathway but rather through the cAMP-dependent exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac)-2 pathway (Figs. 2 and 3) (Gurgul-Convey et al. 2012). Epac2 converts inactive GDP-Rap1 to active GTP-Rap1, which initiates downstream signaling, and potentiates GSIS in a cAMP-dependent manner (Kashima et al. 2001; Yokoyama et al. 2013). Similarly, another IP agonist MRE-269 augmented GSIS in the MIN6 β-cell line (Batchu et al. 2016). The mechanism underlying this increase in GSIS involves PKA-dependent phosphorylation of nephrin (Fig. 3) (Batchu et al. 2016), distinct from what was observed in INS-1E cells. Nephrin is a transmembrane member of the immunoglobulin protein superfamily and has been shown to promote GSIS and induce β-cell survival signaling pathways (Fornoni et al. 2010; Kapodistria et al. 2015). The authors of the latter study did not measure Epac2, thus it is unclear if this pathway also contributes to the observed enhanced GSIS in MIN6 cells. These two studies differ in many aspects, including: 1. PGIS overexpression versus IP agonism; 2. incubation time with different PKA inhibitors (24 h versus 1.5 h); and, 3. stimulatory glucose conditions (30 mM versus 11 mM glucose). These variations in experimental design may contribute to changes in signaling pathways that are altered in response to PGI2 signaling. Despite these differences, these data demonstrate that PGI2 can enhance insulin secretion in β-cell lines, potentially via multiple signaling mechanisms.

Summary of PG receptor signaling. A schematic of some of the proposed signaling mechanisms of PG receptors in the β-cell. Currently, there are no demonstrated effects of DP1, DP2, FP, or EP1 in regulating either β-cell function or mass. EP2 and EP4 improve glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) in vivo, but no mechanism has been determined. EP3 couples to Gi proteins, including GaZ, which inhibit adenylyl cyclase (AC) and reduce islet cAMP levels. However, it is unclear if this is the mechanism responsible for alterations in GSIS and β-cell mass dynamics. In cell lines and rodent islets, EP3 signaling can either inhibit phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) or activate c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), which leads to dephosphorylation and inhibition of Akt. Akt normally phosphorylates and inhibits forkhead box O1 (FoxO1), so upon EP3 signaling, FoxO1 is dephosphorylated and undergoes nuclear translocation. Pancreatic and duodenal homeobox-1 (Pdx1) is important in regulating GSIS, β-cell differentiation, and β-cell mass dynamics, such as proliferation and cell death. FoxO1 and Pdx1 are mutually exclusive in the nucleus, thus providing a potential mechanism for EP3-induced decreases in GSIS and β-cell proliferation. PGI2 via IP signaling results in GS-mediated activation of AC and increased islet cAMP levels. cAMP activates protein kinase A (PKA) or Epac2. In β-cell lines, IP signaling increases GSIS by either PKA activation and phosphorylation of Nephrin or by Epac2 signaling. The IP-induced downstream targets of Epac2 that increase GSIS have not been demonstrated. Dark gray symbols and bold lines indicate PGE2-EP3 signaling pathways. Outlined symbols and block arrows indicate PGI2-IP signaling pathways. Dashed gray symbols represent potential but not confirmed events

In agreement with the effects of PGI2/IP signaling observed in β-cell lines, treatment with the IP agonist selexipag reduced the hyperglycemic effect of STZ injection in C57Bl/6 male mice (Batchu et al. 2016). The decreased hyperglycemia in selexipag-treated mice was due to an increase in plasma insulin levels as observed during an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IP-GTT) and maintenance of β-cell mass (Batchu et al. 2016). The signaling pathways contributing to this enhanced GSIS have yet to be determined. Intriguingly, seleixpag treatment in the absence of STZ had no effect on glucose tolerance or plasma insulin during an IP-GTT (Batchu et al. 2016). Overall, the current literature on PGI2/IP suggests that PGI2 signaling can alter GSIS although there is a dose- and context-dependent role for PGI2 in promoting insulin secretion.

PGE2 and β-cell function

In comparison to the other PGs, the role of PGE2 in β-cell function has been studied in greatest detail. This could stem from early reports demonstrating that the AA metabolite responsible for decreased insulin secretion was PGE2 (Robertson 1988). However, several groups have called into question the solely inhibitory effect of PGE2 on insulin secretion.

There are numerous lines of evidence in support of an inhibitory role of PGE2 on β-cell function in β-cell lines, isolated islets, and in vivo. In vitro studies have demonstrated that PGE2 treatment decreases GSIS in several different β-cell lines, including the HIT-T15, βHC13, and INS-1 (832/3) lines (Kimple et al. 2013; Meng et al. 2009; Robertson et al. 1987; Seaquist et al. 1989). Early studies in the HIT line demonstrated that the action of PGE2 to inhibit GSIS is mediated by a pertussis toxin (PTx)-sensitive mechanism resulting in decreased cAMP levels (Robertson et al. 1987; Seaquist et al. 1989). PTx blocks the action of inhibitory G proteins, excluding GαZ, by ADP-ribosylation on a critical cysteine residue (Fields and Casey 1997). PTx was originally called islet-activating protein (IAP) due to its ability to reverse α-adrenergic inhibition of cAMP and to enhance insulin secretion from islets (Yajima et al. 1978). Since EP3 is the only PGE2 receptor that couples to Gi proteins, these data suggest that EP3 is the receptor responsible for this negative regulation of GSIS. PGE2 also facilitates the inhibitory effect of IL-1β on GSIS in vitro (Tran et al. 1999), providing further evidence in support of an inhibitory role of PGE2 on insulin secretion. Two structurally different COX-2 inhibitors were able to reverse the decreased GSIS in response to IL-1β treatment in HIT-T15 and βHC13 lines in part by decreasing PGE2 production. When exogenous PGE2 was added back to these cells, GSIS was once again decreased. The mechanism of action was not determined but the authors predicted that PGE2 signaling through the EP3 receptor is responsible for the observed decrease in GSIS (Tran et al. 1999).

Many of the in vitro data described above have been mirrored in in vivo settings and in isolated islets. Intravenous infusion of PGE2 decreased circulating insulin levels and GSIS in vivo in early studies using animal models and humans (Giugliano et al. 1983; Robertson et al. 1974; Sacca et al. 1975). As discussed previously, Burr and Sharp demonstrated that PGE1 inhibited both first and second phases of GSIS in isolated rat islets in 1974 (Burr and Sharp 1974). PGE2 differs from PGE1 in terms of side chain unsaturation: PGE1 contains one double bond whereas PGE2 has two double bonds (Speroff and Ramwell 1970); both PGE1 and PGE2 can act as agonists for the EP receptors (Breyer et al. 2001). The effects of PGE on insulin secretion were confirmed in later studies in which isolated rat islets (Meng et al. 2009; Meng et al. 2006; Metz et al. 1981; Sjoholm 1996; Tran et al. 2002) or mouse islets (Meng et al. 2009; Parazzoli et al. 2012) were incubated in the presence of PGE2 and demonstrated again that PGE2 treatment decreases GSIS. In rat islets, treatment with sodium salicylate, a COX-2 inhibitor, decreased PGE2 production and augmented GSIS (Metz et al. 1981). However, in contrast to what was observed in cell lines, inhibition of GSIS by PGE2 was not reversed upon PTx treatment (Sjoholm 1996). This may be explained by PGE2 signaling through the PTx-insensitive inhibitory G protein, GαZ, discussed in more detail below. PGE2 also mediates the negative effect of IL-1β on GSIS in isolated rat islets (Tran et al. 2002), as was described in β-cell lines above. Here, treatment of isolated islets with sodium salicylate blocked the IL-1β-induced decrease in GSIS (Tran et al. 2002).

PGE2 also affects β-cell function in vivo in mice. Increased production of PGE2 in vivo results in hyperglycemia and impaired glucose homeostasis in a transgenic mouse model (Oshima et al. 2006). When COX-2 and the microsomal PGE2 synthase-1 (mPGES-1) were overexpressed in mouse β-cells as a way to induce PGE2 production, homozygous mice developed chronic hyperglycemia beginning at six weeks of age (Oshima et al. 2006). Heterozygous mice were euglycemic but displayed impaired glucose homeostasis due to a decrease in plasma insulin levels during an IP-GTT (Oshima et al. 2006). Thus, in many different experimental paradigms, PGE2 decreases GSIS.

The mechanism for PGE2-induced inhibition of insulin secretion downstream of Gi-/ GαZ-coupling has yet to be definitively determined but there is evidence for involvement of FoxO1. In rodent islets and the β-cell line HIT-TI5, decreased GSIS in response to PGE2 occurred via activation of the FoxO1 pathway by either activation of c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase (JNK1) or inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) (Meng et al. 2009; Meng et al. 2006). Here, PGE2 activates JNK-1 or inhibits PI3K leading to decreased phosphorylation of Akt and FoxO1 (Figure 3). Akt normally phosphorylates FoxO1, retaining it in the cytoplasm (Brunet et al. 1999). In islets, PGE2 inactivates Akt (Meng et al. 2009; Meng et al. 2006) thereby decreasing the inhibitory action of Akt on FoxO1. Hypophosphorylated FoxO1 translocates to the nucleus of β-cells where it participates in nuclear exclusion of the critical β-cell transcription factor Pancreatic and Duodenal Homeobox 1 (Pdx1) (Kitamura et al. 2002; Meng et al. 2009). As Pdx1 regulates genes that promote GSIS (Ahlgren et al. 1998; Khoo et al. 2012), this may explain the inhibitory role of PGE2 on insulin secretion (Figure 3).

While there is a great deal of data indicating that PGE2 inhibits GSIS, its role in this process is still controversial. An early study using rat islets found that PGE2 did not affect GSIS using a wide range of doses (Hughes et al. 1989). In addition, several groups have reported that exogenous PGE2 has no effect on GSIS in isolated rodent (Heitmeier et al. 2004; Zawalich et al. 2007) and human islets (Heitmeier et al. 2004; Persaud et al. 2007), as measured by several different techniques. Intriguingly, PGE2 treatment stimulated insulin release from human islets during substimulatory glucose conditions (Persaud et al. 2007). Finally, in contrast to the studies described above (Tran et al. 1999), several studies have failed to demonstrate that COX-2 inhibition can rescue the inhibitory effects of IL-1β on GSIS in rat (Heitmeier et al. 2004; Hughes et al. 1989; Sjoholm 1996) or human islets (Heitmeier et al. 2004), suggesting that PGE2 is not required for the negative effects of IL-1β on insulin release.

The reasons for the inconsistencies described for the role of PGE2 in regulating β-cell function are not readily apparent. Clearly it is not due to differences in experimental protocols for measuring insulin secretion, including static incubation and perifusion assays, as each have been used in both sides of the argument. However, initial perifusion assays demonstrated that the inhibitory effect of PGE2 on GSIS could only be observed during the first phase of insulin secretion and not in response to additional secretagogues (Robertson et al. 1974). Thus, static incubation studies may miss an effect of PGE2 since first phase secretion cannot be assessed by this methodology. Concentration of PGE2 does not account for the observed differences as similar doses of exogenous PGE2 (mainly 1 μM and 10 μM) have been used in all of the studies. One possible explanation for these discrepancies could be due to differences in experimental tissue studied. While β-cell lines have been used to demonstrate that PGE2 impairs GSIS, none of the studies failing to observe an effect of PGE2 used cell lines. However, there are examples of PGE2 either having no effect or a negative effect on β-cell function in isolated islets. One group has suggested that variations in the culture media used prior to GSIS assays could explain some of these inconsistencies (Heitmeier et al. 2004). In a few of the reports demonstrating a negative role for PGE2 in GSIS, islets were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 11 mM glucose following islet isolation (Tran et al. 1999; Tran et al. 2002). In contrast, when islets were cultured in CMRL-1066 medium containing 5 mM glucose following isolation, no effect of PGE2 on GSIS was observed (Heitmeier et al. 2004). Indeed, as already discussed, high glucose conditions induce production of PGE2 and thus could be affecting the results of exogenous PGE2 on insulin secretion. While it is difficult to draw concrete conclusions from all of these data, similar to PGI2 discussed above, it is likely that there are context-dependent roles for PGE2 in GSIS, including in β-cell lines (Kimple et al. 2013; Meng et al. 2009; Meng et al. 2006; Robertson et al. 1987; Seaquist et al. 1989; Tran et al. 1999), fetal rodent islets (Metz et al. 1981; Sjoholm 1996), T2D mouse islets (Kimple et al. 2013), and isolated islets cultured in high glucose (Meng et al. 2009; Meng et al. 2006; Tran et al. 1999; Tran et al. 2002).

Another possible explanation for the discrepancies in PGE2 effects on insulin secretion is that the different experimental conditions alter PGE2 signaling through its different receptors. There are four EP receptors, all of which are expressed in islets, as described earlier. Most of the literature suggests PGE2 signaling via the EP3 receptor is responsible for decreased GSIS. Based on its inhibitory G protein signaling properties, one would predict that EP3 decreases GSIS whereas signaling via EP1-Gq or EP2/EP4-GS would increase GSIS.

There is very little known in regards to the action of EP1, EP2, and EP4 on insulin secretion. The EP1 antagonist, AH-6809, does not affect GSIS alone nor does it alter the action of IL-1β on GSIS (Tran et al. 2002). Further, the effect of STZ on glycemia in mice with a global deletion of EP1 does not differ from control mice (Vennemann et al. 2012). These data suggest that EP1 does not affect GSIS.

EP2 and EP4 have been shown to indirectly promote insulin secretion. EP2-null mice treated with STZ and the EP4 antagonist ONO-AE3–208 have worsened STZ-induced hyperglycemia due to decreased plasma insulin (Vennemann et al. 2012). Interestingly, EP2-null mice treated with STZ and the EP4 agonist ONO-AE1–329 showed an improvement in glycemia. Further, control STZ-injected mice treated with ONO-AE1–259-01 (EP2 agonist) and ONO-AE1–329 (EP4 agonist) concurrently had even further protection against STZ-induced hyperglycemia compared to the EP2-null + EP4 agonist treated mice (Vennemann et al. 2012). However, there were no direct measurements of GSIS in this study. In the T2D db/db mouse model, the EP4 agonist ONO-AE1–329 improved glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity as measured by IP-GTT and an insulin tolerance test (ITT); although, plasma insulin levels were not determined (Yasui et al. 2015). Although the mechanism is unknown, these data suggest that EP2 and EP4 promote insulin secretion in vivo.

In general, the literature supports an inhibitory role of EP3 in GSIS. EP3 signals through inhibitory Gi proteins, including GαZ, all of which decrease cAMP production (Kimple et al. 2012; Kimple et al. 2005). In rat islets, treatment with the EP3 agonists misoprostol or sulprostone decreased GSIS during a static incubation assay (Tran et al. 2002). This decrease in GSIS was reversed when islets were pre-treated with PTx before addition of the EP3 agonists (Tran et al. 2002), demonstrating that EP3 can signal through Gi proteins in rat islets. In islets from C57Bl/6 ob/ob mice, the EP3 agonist sulprostone also decreased GSIS in a static incubation (Kimple et al. 2012). However, PTx treatment, which inactivates all Gi proteins except GαZ, did not relieve the observed inhibition of sulprostone on GSIS (Kimple et al. 2012). This suggests that, at least in the context of ob/ob mice, GαZ is the primary G protein coupled to EP3. GαZ itself negatively regulates GSIS in the INS-1 (832/13) β-cell line (Kimple et al. 2005), in vivo in mice (Kimple et al. 2008), and in isolated islets (Kimple et al. 2012). These conflicting data using PTx suggest that EP3 likely couples to multiple inhibitory G proteins in islets, perhaps depending on the context. The diversity of the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of EP3 results in alterations in G protein coupling and differences in constitutive versus ligand-dependent activity (Hata and Breyer 2004). There are three EP3 receptor isoforms in mouse (EP3α, EP3β, and EP3γ) generated by alterative splicing of the C-terminal tail and at least eight EP3 isoforms have been identified in humans (Breyer et al. 2001).

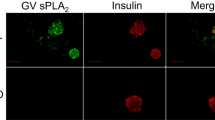

Additional studies using EP3 agonists and antagonists have also demonstrated that EP3 plays an inhibitory role in GSIS. Islets from the T2D mouse model, BTBRob/ob, have increased GSIS when treated with the EP3 antagonist L-798,106 yet decreased GSIS after stimulation with PGE1 (Kimple et al. 2013). In human islets, the EP3 antagonist L-798,106 does not affect GSIS in islets from non-diabetic donors, yet improves insulin secretion in islets from donors with T2D (Kimple et al. 2013). Interestingly, Ptger3 gene expression is upregulated in islets from BTBRob/ob mice, obese humans, and humans with T2D (Kimple et al. 2013). Thus, an increase in EP3 expression may contribute to the impaired β-cell function in these settings. A recent study has demonstrated that PGE2-EP3 signaling plays a role in the negative effects of E. coli infection on insulin secretion in INS-1E cells (Caporarello et al. 2016). Treatment with the EP3 antagonist L-798,106 restored GSIS in response to long-term E. coli infection whereas the EP3 agonist sulprostone did not (Caporarello et al. 2016). The EP3 antagonist L-798,106 also improves GSIS in MIN6 cells and isolated mouse islets (Shridas et al. 2014). Here, the authors demonstrated that the Group X secretory phospholipase, phospholipase A2 (GX sPLA2), which hydrolyzes phosphatidylcholine from the plasma membrane resulting in PGE2 production (Shridas et al. 2014), was involved in suppression of GSIS via PGE2-EP3 signaling. Thus, several lines of evidence indicate that the EP3 receptor serves to mediate the negative effect of PGE2 on GSIS.

Surprisingly, one study reported that pharmacological blockade of EP3 using the antagonist DG-041 does not alter GSIS in islets from wild-type mice fed a chow diet or in non-diabetic human islets (Ceddia et al. 2016). While these data differ from those described above, it suggests that EP3 only affects GSIS in specific contexts. Pharmacological inhibition of EP3 only restored GSIS in the setting of T2D both in mouse and human islets (Kimple et al. 2013). Thus, the effects of inhibiting EP3 may only be observed during situations in which β-cell dysfunction is already present. Additionally, our group showed that global loss of EP3 (EP3−/−) in mice did not affect GSIS as assessed by a perifusion assay (Ceddia et al. 2016). Islets from EP3−/− mice fed a chow diet or high fat diet (HFD) for 21 weeks had insulin secretion profiles that were indistinguishable from control mice (Ceddia et al. 2016). A caveat to this study is that EP3−/− mice on HFD gained more weight than control HFD animals and displayed hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance, consistent with what had been previously reported (Sanchez-Alavez et al. 2007). Consequently, being able to parse apart the peripheral effects of EP3 from its role in β-cell function awaits conditional gene inactivation. It is possible that EP3 plays a role only in in vivo GSIS under specific circumstances, such as during T2D, as observed in isolated islets.

PGs and regulation of β-cell mass

In addition to improving β-cell function, expansion of β-cell mass is another mechanism to increase insulin output in order to maintain euglycemia in the face of increased metabolic demand. β-Cell mass can be increased by proliferation (hyperplasia), hypertrophy, or neogenesis and decreased by cell death or dedifferentiation (reviewed in (Jung et al. 2014)). In rodent models, adult β-cell mass expansion occurs as a result of increased replication (Dor et al. 2004). Additionally, increased proliferation occurs during HFD-induced obesity in mouse models as a way to expand β-cell mass (Linnemann et al. 2014). Human autopsy studies reveal that non-diabetic obese individuals have higher β-cell mass than lean non-diabetic subjects (Butler et al. 2003; Saisho et al. 2013). However, β-cell mass is reduced in humans with T2D in both lean and obese settings (Butler et al. 2003). β-Cell death is also increased in humans with T2D (Butler et al. 2003), which may contribute to failure to maintain proper β-cell mass. Thus, it appears that expansion and regulation of β-cell mass is an important feature in preventing T2D.

In comparison to the literature on PGs and β-cell function, less is known about their role in regulating β-cell mass. Again, a majority of the available data focuses on PGE2 and its receptors. To our knowledge, there are no reports on PGD2 and β-cell mass dynamics. Further, there is very little evidence to suggest a role for PGF2α in this process. In one study performed in rat islets, PGF2α had no effect on DNA synthesis (Sjoholm 1996). In this section, we will discuss the available information on PGI2, PGE2, and their receptors with regard to their roles in regulating β-cell mass.

PGI2 and regulation of β-cell mass

The PGI2 analog beraprost sodium improves islet viability during islet isolation in a canine model (Arita et al. 2001), suggesting that PGI2 may regulate β-cell mass by enhancing β-cell survival. Indeed, in multiple β-cell lines, PGI2 and its receptor IP play a positive role in protecting against cell death (Gurgul-Convey et al. 2012; Gurgul-Convey and Lenzen 2010). Overexpression of PGIS in the RINm5F β-cell line improved cell viability following cytokine treatment (Gurgul-Convey and Lenzen 2010). The protective effect of PGIS overexpression corresponded with prevention of caspase-3, −12, and −9 activation, decreased Chop expression (a marker of ER stress), decreased activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NFκB), and blockade of the nitric oxide (NO) pathway. Interestingly, PGIS overexpression also prevented the cytokine-mediated reduction in cell proliferation (Gurgul-Convey and Lenzen 2010). These data suggest that PGI2 may protect against cytokine toxicity by not only decreasing cell death and but also by maintaining normal proliferation levels. In the INS-1E β-cell line, the IP antagonist CAY10441 decreases cell viability and cell proliferation in both control and PGIS-overexpressing cells (Gurgul-Convey et al. 2012). CAY10441 also induces caspase-3 activation in control cells while the IP agonist iloprost does not. Surprisingly, iloprost did not alter cell viability or proliferation itself. Overexpression of PGIS also increased cell proliferation but only during high glucose conditions (Gurgul-Convey et al. 2012). Thus, high levels of PGI2 and signaling via the IP receptor play cytoprotective roles in β-cell lines.

Activation of the IP receptor also plays a protective role in vivo. As already discussed, the IP agonist selexipag augmented GSIS in response to STZ treatment. This can be in part attributed to a preservation of β-cell mass in response to STZ (Batchu et al. 2016). However, in the absence of STZ, two-week administration of selexipag does not affect β-cell mass (Batchu et al. 2016). The in vivo mechanism for preservation of β-cell mass in response to STZ is unknown; however, evidence from β-cell lines suggest that it may be by protecting against cell death and maintaining proliferation.

PGE2 and regulation of β-cell mass

PGE2 alters several mechanisms responsible for regulating β-cell mass, including replication and cell death. However, as discussed in the following section, PGE2 treatment can have different outcomes due to signaling through its different receptors, which couple to different downstream second messenger pathways.

In fetal rat islets, treatment with PGE2 results in decreased DNA synthesis (Sjoholm 1996), suggesting that PGE2 negatively regulates β-cell proliferation. In support of this notion, when PGE2 production is increased in vivo using a transgenic mouse model of mPGES-1 and COX-2 overexpression, there is an observed decrease in β-cell ratio per islet and a corresponding decrease in total cell proliferation (Oshima et al. 2006). However, in these studies the immunolabeling for Brd-U incorporation (cell cycle marker) was not counterlabeled for insulin, therefore one cannot comment specifically on the change in β-cell proliferation. Interestingly, there was an increase in α-cell ratio per islet in this mouse model (Oshima et al. 2006); it is unknown how PGE2 alters α-cell number.

The available literature suggests that a PGE2-induced decrease in β-cell proliferation is the result of signaling via the EP3 receptor. Indeed, our group found that EP3−/− mice fed a HFD for 16 weeks have significantly increased β-cell proliferation compared to control mice on HFD; however, β-cell mass is not different between genotype (Ceddia et al. 2016). Intriguingly, chow-fed EP3−/− mice do not have altered β-cell proliferation compared to control mice (Ceddia et al. 2016), suggesting that EP3 activity only inhibits proliferation during specific circumstances, such as HFD feeding. Further support of an inhibitory role of EP3 on β-cell proliferation comes from its downstream signaling proteins, specifically GαZ. Global loss of GαZ in mice results in increased β-cell proliferation in chow- and HFD-fed animals and a corresponding increase in β-cell mass in HFD-fed mice (Kimple et al. 2012). The PGE2-EP3 signaling pathways downstream of G protein coupling responsible for mediating changes in β-cell proliferation and mass expansion during HFD-induced obesity are currently unknown. Based on the existing literature and our knowledge of β-cell differentiation and proliferation, we hypothesize that a model similar to that described for GSIS is involved in mediating the effects of PGE2-EP3 on β-cell proliferation and mass (Figure 3). We predict that increased PGE2 production and Ptger3 (EP3) expression by hyperglycemia leads to activation of JNK and deactivation of Akt, resulting in hypophosphorylation and nuclear translocation of FoxO1, and therefore nuclear exclusion of Pdx1. Since Pdx1 is essential for maintenance of the β-cell differentiated state and is critical for β-cell mass expansion (Ahlgren et al. 1998; Dutta et al. 1998), this may provide an explanation for impaired β-cell proliferation in response to EP3 signaling. We are unaware of any reports revealing a role for EP1, EP2, or EP4 in β-cell proliferation. We predict that EP2 and/or EP4 signaling would enhance β-cell proliferation through GS mechanisms to inhibit FoxO1 activity.

PGE2 has also been implicated in regulating β-cell survival, another mechanism that can be involved in altering β-cell mass. Cytokines, such as IL-1β, which are known to induce β-cell death (Heitmeier et al. 1997), induce the expression of Ptgs2 (COX-2) and increase production of PGE2 in isolated rodent and human islets with a corresponding decrease in cell viability (Heitmeier et al. 2004). PGE2 treatment decreased cell viability in the β-cell line HIT-T15, yet did not alter apoptosis or cell cycle progression (Meng et al. 2006). In contrast, exogenous PGE2 decreased the level of apoptosis and caspase-3 activity in the MIN-6 β-cell line (Papadimitriou et al. 2007). Interestingly, combined PGE2 and IL-1β treatment in the β-cell line INS-1 (832/13) decreased Ptger3 (EP3) and increased Ptger4 (EP4) expression (Burke and Collier 2011). Based on their signaling properties and evidence from other tissue types, these data suggest that signaling via EP3 promotes cell death whereas EP4 protects against cell death. In support of this notion, RNA-sequencing of islets from a transgenic mouse model of enhanced β-cell survival developed in our laboratory, called β-Foxm1*, revealed that Ptger3 expression was reduced while Ptger4 was increased (Golson et al. 2014). GαZ has also recently been shown to be involved in β-cell death. GαZ-null mice treated with STZ show decreased β-cell death in addition to increased β-cell proliferation and compared to control mice (Brill et al. 2016). In response to another stimulus of cell death, IL-1β, islets from GαZ-null animals show no induction of ER stress or pro-apoptotic genes as was observed in control islets (Brill et al. 2016). Taken together, these data demonstrate a role for GαZ signaling, and likely EP3, in β-cell proliferation and β-cell death. While the mechanism for PGE2 in β-cell death has not been definitively established, we hypothesize that PGE2 signaling via EP4 plays a protective role against β-cell death by GS-mediated maintenance of Pdx1 whereas EP3 enhances β-cell death by FoxO1 activation and nuclear exclusion of Pdx1 (Fig. 3).

Conclusions

Failure to maintain proper β-cell mass and deterioration of β-cell function are hallmarks of T2D. AA-derived PGs play important roles during β-cell dysfunction and insulin secretion. While all PG members are synthesized within islets, there is little to nothing known about TXA2, PGD2, and PGF2α in the context of pancreatic islets. As discussed in this review, PGE2 has, in general, been implicated in regulation of insulin secretion, β-cell mass, and β-cell survival during specific circumstances. To date, EP3 has primarily been shown to mediate the effects of PGE2 on β-cells and little is known about the function of the other EP receptors in islets. In contrast, PGI2, by way of the IP receptor, promotes insulin secretion in β-cell lines and protects against STZ-induced hyperglycemia in mice via maintenance of β-cell mass and plasma insulin levels. Despite this evidence, the detailed mechanisms by which PGs exert these effects remain largely unknown.

GPCRs are therapeutic targets for approximately 50–60% of all drugs currently on the market (Lundstrom 2009), including some of the newer T2D therapeutics targeting the glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor using GLP-1 agonists, such as Exenatide, Liraglutide, and Lixisenatide. The GLP-1 receptor couples to GS and enhances rodent β-cell proliferation (Kimple et al. 2014). However, not all T2D patients respond to GLP-1-based therapies (Anderson et al. 2003), suggesting that the activity of other Gi-coupled GPCRs, such as EP3, within islets may be counteracting the effects of GLP-1 signaling. Designing drugs that can inhibit negatively acting GPCRs in tandem with activation of positively acting GPCRs may provide enhanced benefit in the treatment of T2D. For example, targeting both GLP-1 and/or IP and blocking the action of EP3 could lead to not only improved GSIS but also enhanced β-cell proliferation and protection against β-cell death. Since PG receptors are not expressed solely in β-cells, it will be important to develop compounds that are targeted directly to β-cells. Caution should be taken in these efforts as chronic stimulation of insulin secretion can result in β-cell exhaustion and subsequent apoptosis, as has been described for sulfonylureas (Del Prato and Pulizzi 2006). Nonetheless, there is still a great deal to be learned before PGs and their receptors are suitable targets for T2D therapeutics.

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

Arachidonic Acid

- COX:

-

cyclooxygenase

- Epac2:

-

Exchange Protein Directly Activated by cAMP 2

- GPCR:

-

G-Protein Coupled Receptor

- GLP-1:

-

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1

- HFD:

-

High Fat Diet

- IL-1β:

-

Interleukin 1-β

- ITT:

-

Insulin Tolerance Test

- IP-GTT:

-

Intraperitoneal Glucose Tolerance Test

- JNK:

-

c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase

- mPGES-1:

-

microsomal PGE2 Synthase 1

- NSAIDs:

-

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

- NFκB:

-

Nuclear Factor κB

- Pdx1:

-

Pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1

- PTx:

-

Pertussis Toxin

- PI3K:

-

Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase

- PLA2 :

-

Phospholipase A2

- PG:

-

Prostaglandin

- PKA:

-

Protein Kinase A

- SNP:

-

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

- STZ:

-

Streptozotocin

- T2D:

-

Type 2 Diabetes

References

Abramovitz M, Adam M, Boie Y, Carriere M, Denis D, Godbout C, Lamontagne S, Rochette C, Sawyer N, Tremblay NM et al (2000) The utilization of recombinant prostanoid receptors to determine the affinities and selectivities of prostaglandins and related analogs. Biochim Biophys Acta 1483:285–293

Ahlgren U, Jonsson J, Jonsson L, Simu K, Edlund H (1998) Beta-cell-specific inactivation of the mouse Ipf1/Pdx1 gene results in loss of the beta-cell phenotype and maturity onset diabetes. Genes Dev 12:1763–1768

Ahren B (2009) Islet G protein-coupled receptors as potential targets for treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8:369–385

Akpan JO, Hurley MC, Pek S, Lands WE (1979) The effects of prostaglandins on secretion of glucagon and insulin by the perfused rat pancreas. Can J Biochem 57:540–547

Anderson SL, Trujillo JM, McDermott M, Saseen JJ (2012) Determining predictors of response to exenatide in type 2 diabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc 52:466–471

Arita S, Une S, Ohtsuka S, Kawahara T, Kasraie A, Smith CV, Mullen Y (2001) Increased islet viability by addition of beraprost sodium to collagenase solution. Pancreas 23:62–67

Batchu SN, Majumder S, Bowskill BB, White KE, Advani SL, Brijmohan AS, Liu Y, Thai K, Azizi PM, Lee WL et al (2016) Prostaglandin I2 receptor agonism preserves beta-cell function and attenuates albuminuria through nephrin-dependent mechanisms. Diabetes 65:1398–1409

Bramswig NC, Everett LJ, Schug J, Dorrell C, Liu C, Luo Y, Streeter PR, Naji A, Grompe M, Kaestner KH (2013) Epigenomic plasticity enables human pancreatic alpha to beta cell reprogramming. J Clin Invest 123:1275–1284

Breyer RM, Bagdassarian CK, Myers SA, Breyer MD (2001) Prostanoid receptors: subtypes and signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 41:661–690

Brill AL, Wisinski JA, Cadena MT, Thompson MF, Fenske RJ, Brar HK, Schaid MD, Pasker RL, Kimple ME (2016) Synergy between Galphaz deficiency and GLP-1 analog treatment in preserving functional beta-cell mass in experimental diabetes. Mol Endocrinol 30:543–556

Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, Anderson MJ, Arden KC, Blenis J, Greenberg ME (1999) Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a forkhead transcription factor. Cell 96:857–868

Burke SJ, Collier JJ (2011) The gene encoding cyclooxygenase-2 is regulated by IL-1beta and prostaglandins in 832/13 rat insulinoma cells. Cell Immunol 271:379–384

Burr IM, Sharp R (1974) Effects of prostaglandin E1 and of epinephrine on the dynamics of insulin release in vitro. Endocrinology 94:835–839

Butler AE, Janson J, Bonner-Weir S, Ritzel R, Rizza RA, Butler PC (2003) Beta-cell deficit and increased beta-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 52:102–110

Caporarello N, Salmeri M, Scalia M, Motta C, Parrino C, Frittitta L, Olivieri M, Cristaldi M, Avola R, Bramanti V et al (2016) Cytosolic and calcium-independent phospholipases A2 activation and prostaglandins E2 are associated with Escherichia Coli-induced reduction of insulin secretion in INS-1E cells. PLoS One 11:e0159874

Ceddia RP, Lee D, Maulis MF, Carboneau BA, Threadgill DW, Poffenberger G, Milne G, Boyd KL, Powers AC, McGuinness OP et al (2016) The PGE2 EP3 receptor regulates diet-induced adiposity in male mice. Endocrinology 157:220–232

Del Prato S, Pulizzi N (2006) The place of sulfonylureas in the therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 55:S20–S27

Dor Y, Brown J, Martinez OI, Melton DA (2004) Adult pancreatic beta-cells are formed by self-duplication rather than stem-cell differentiation. Nature 429:41–46

Dutta S, Bonner-Weir S, Montminy M, Wright C (1998) Regulatory factor linked to late-onset diabetes? Nature 392:560

Ebstein W (1876) Zur therapie des diabetes mellitus, insbesondere uber die anewendeng des salicylsauren natron bei demselben. Klin Worshensche:337–340

Evans MH, Pace CS, Clements RS Jr (1983) Endogenous prostaglandin synthesis and glucose-induced insulin secretion from the adult rat pancreatic islet. Diabetes 32:509–515

Fields TA, Casey PJ (1997) Signalling functions and biochemical properties of pertussis toxin-resistant G-proteins. Biochem J 321(Pt 3):561–571

Fornoni A, Jeon J, Varona Santos J, Cobianchi L, Jauregui A, Inverardi L, Mandic SA, Bark C, Johnson K, McNamara G et al (2010) Nephrin is expressed on the surface of insulin vesicles and facilitates glucose-stimulated insulin release. Diabetes 59:190–199

Giugliano D, Di Pinto P, Torella R, Frascolla N, Saccomanno F, Passariello N, D'Onofrio F (1983) A role for endogenous prostaglandin E in biphasic pattern of insulin release in humans. Am J Phys 245:E591–E597

Golson ML, Misfeldt AA, Kopsombut UG, Petersen CP, Gannon M (2010) High fat diet regulation of beta-cell proliferation and beta-cell mass. Open Endocrinol J 4. doi:10.2174/1874216501004010066

Golson ML, Maulis MF, Dunn JC, Poffenberger G, Schug J, Kaestner KH, Gannon MA (2014) Activated FoxM1 attenuates streptozotocin-mediated beta-cell death. Mol Endocrinol 28:1435–1447

Gunasekaran U, Gannon M (2011) Type 2 diabetes and the aging pancreatic beta cell. Aging (Albany NY) 3:565–575

Gurgul-Convey E, Lenzen S (2010) Protection against cytokine toxicity through endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial stress prevention by prostacyclin synthase overexpression in insulin-producing cells. J Biol Chem 285:11121–11128

Gurgul-Convey E, Hanzelka K, Lenzen S (2012) Mechanism of prostacyclin-induced potentiation of glucose-induced insulin secretion. Endocrinology 153:2612–2622

Hata AN, Breyer RM (2004) Pharmacology and signaling of prostaglandin receptors: multiple roles in inflammation and immune modulation. Pharmacol Ther 103:147–166

Heitmeier MR, Scarim AL, Corbett JA (1997) Interferon-gamma increases the sensitivity of islets of Langerhans for inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression induced by interleukin 1. J Biol Chem 272:13697–13704

Heitmeier MR, Kelly CB, Ensor NJ, Gibson KA, Mullis KG, Corbett JA, Maziasz TJ (2004) Role of cyclooxygenase-2 in cytokine-induced beta-cell dysfunction and damage by isolated rat and human islets. J Biol Chem 279:53145–53151

Hellstrom-Lindahl E, Danielsson A, Ponten F, Czernichow P, Korsgren O, Johansson L, Eriksson O (2016) GPR44 is a pancreatic protein restricted to the human beta cell. Acta Diabetol 53:413–421

Hughes JH, Easom RA, Wolf BA, Turk J, McDaniel ML (1989) Interleukin 1-induced prostaglandin E2 accumulation by isolated pancreatic islets. Diabetes 38:1251–1257

Jung KY, Kim KM, Lim S (2014) Therapeutic approaches for preserving or restoring pancreatic beta-cell function and mass. Diabetes Metab J 38:426–436

Kapodistria K, Tsilibary EP, Politis P, Moustardas P, Charonis A, Kitsiou P (2015) Nephrin, a transmembrane protein, is involved in pancreatic beta-cell survival signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol 400:112–128

Kashima Y, Miki T, Shibasaki T, Ozaki N, Miyazaki M, Yano H, Seino S (2001) Critical role of cAMP-GEFII--Rim2 complex in incretin-potentiated insulin secretion. J Biol Chem 276:46046–46053

Kelly KL, Laychock SG (1981) Prostaglandin synthesis and metabolism in isolated pancreatic islets of the rat. Prostaglandins 21:759–769

Kelly KL, Laychock SG (1984) Activity of prostaglandin biosynthetic pathways in rat pancreatic islets. Prostaglandins 27:925–938

Khoo C, Yang J, Weinrott SA, Kaestner KH, Naji A, Schug J, Stoffers DA (2012) Research resource: the pdx1 cistrome of pancreatic islets. Mol Endocrinol 26:521–533

Kimple ME, Nixon AB, Kelly P, Bailey CL, Young KH, Fields TA, Casey PJ (2005) A role for G(z) in pancreatic islet beta-cell biology. J Biol Chem 280:31708–31713

Kimple ME, Joseph JW, Bailey CL, Fueger PT, Hendry IA, Newgard CB, Casey PJ (2008) Galphaz negatively regulates insulin secretion and glucose clearance. J Biol Chem 283:4560–4567

Kimple ME, Moss JB, Brar HK, Rosa TC, Truchan NA, Pasker RL, Newgard CB, Casey PJ (2012) Deletion of GalphaZ protein protects against diet-induced glucose intolerance via expansion of beta-cell mass. J Biol Chem 287:20344–20355

Kimple ME, Keller MP, Rabaglia MR, Pasker RL, Neuman JC, Truchan NA, Brar HK, Attie AD (2013) Prostaglandin E2 receptor, EP3, is induced in diabetic islets and negatively regulates glucose- and hormone-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes 62:1904–1912

Kimple ME, Neuman JC, Linnemann AK, Casey PJ (2014) Inhibitory G proteins and their receptors: emerging therapeutic targets for obesity and diabetes. Exp Mol Med 46:e102

Kitamura T, Nakae J, Kitamura Y, Kido Y, Biggs WH 3rd, Wright CV, White MF, Arden KC, Accili D (2002) The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 links insulin signaling to Pdx1 regulation of pancreatic beta cell growth. J Clin Invest 110:1839–1847

Konheim YL, Wolford JK (2003) Association of a promoter variant in the inducible cyclooxygenase-2 gene (PTGS2) with type 2 diabetes mellitus in pima Indians. Hum Genet 113:377–381

Ku GM, Kim H, Vaughn IW, Hangauer MJ, Myung Oh C, German MS, McManus MT (2012) Research resource: RNA-Seq reveals unique features of the pancreatic beta-cell transcriptome. Mol Endocrinol 26:1783–1792

Lindskog C, Korsgren O, Ponten F, Eriksson JW, Johansson L, Danielsson A (2012) Novel pancreatic beta cell-specific proteins: antibody-based proteomics for identification of new biomarker candidates. J Proteome 75:2611–2620

Linnemann AK, Baan M, Davis DB (2014) Pancreatic beta-cell proliferation in obesity. Adv Nutr 5:278–288

Lundstrom K (2009) An overview on GPCRs and drug discovery: structure-based drug design and structural biology on GPCRs. Methods Mol Biol 552:51–66

Luo P, Wang MH (2011) Eicosanoids, beta-cell function, and diabetes. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 95:1–10

Meng ZX, Sun JX, Ling JJ, Lv JH, Zhu DY, Chen Q, Sun YJ, Han X (2006) Prostaglandin E2 regulates Foxo activity via the Akt pathway: implications for pancreatic islet beta cell dysfunction. Diabetologia 49:2959–2968

Meng Z, Lv J, Luo Y, Lin Y, Zhu Y, Nie J, Yang T, Sun Y, Han X (2009) Forkhead box O1/pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 intracellular translocation is regulated by c-Jun N-terminal kinase and involved in prostaglandin E2-induced pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction. Endocrinology 150:5284–5293

Metz SA, Robertson RP, Fujimoto WY (1981) Inhibition of prostaglandin E synthesis augments glucose-induced insulin secretion is cultured pancreas. Diabetes 30:551–557

Oshima H, Taketo MM, Oshima M (2006) Destruction of pancreatic beta-cells by transgenic induction of prostaglandin E2 in the islets. J Biol Chem 281:29330–29336

Papadimitriou A, King AJ, Jones PM, Persaud SJ (2007) Anti-apoptotic effects of arachidonic acid and prostaglandin E2 in pancreatic beta-cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 20:607–616

Parazzoli S, Harmon JS, Vallerie SN, Zhang T, Zhou H, Robertson RP (2012) Cyclooxygenase-2, not microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1, is the mechanism for interleukin-1beta-induced prostaglandin E2 production and inhibition of insulin secretion in pancreatic islets. J Biol Chem 287:32246–32253

Patrono C, Pugliese F, Ciabattoni G, Di Blasi S, Pierucci A, Cinotti GA, Maseri A, Chierchia S (1981) Prostacyclin does not affect insulin secretion in humans. Prostaglandins 21:379–385

Persaud SJ, Burns CJ, Belin VD, Jones PM (2004) Glucose-induced regulation of COX-2 expression in human islets of Langerhans. Diabetes 53(Suppl 1):S190–S192

Persaud SJ, Muller D, Belin VD, Papadimitriou A, Huang GC, Amiel SA, Jones PM (2007) Expression and function of cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase enzymes in human islets of Langerhans. Arch Physiol Biochem 113:104–109

Robertson RP (1983) Prostaglandins, glucose homeostasis, and diabetes mellitus. Annu Rev Med 34:1–12

Robertson RP (1988) Eicosanoids as pluripotential modulators of pancreatic islet function. Diabetes 37:367–370

Robertson RP, Gavareski DJ, Porte D Jr, Bierman EL (1974) Inhibition of in vivo insulin secretion by prostaglandin E1. J Clin Invest 54:310–315

Robertson RP, Tsai P, Little SA, Zhang HJ, Walseth TF (1987) Receptor-mediated adenylate cyclase-coupled mechanism for PGE2 inhibition of insulin secretion in HIT cells. Diabetes 36:1047–1053

Sacca L, Perez G, Rengo F, Pascucci I, Condorelli M (1975) Reduction of circulating insulin levels during the infusion of different prostaglandins in the rat. Acta Endocrinol 79:266–274

Sachdeva MM, Stoffers DA (2009) Minireview: meeting the demand for insulin: molecular mechanisms of adaptive postnatal beta-cell mass expansion. Mol Endocrinol 23:747–758

Saisho Y, Butler AE, Manesso E, Elashoff D, Rizza RA, Butler PC (2013) Beta-cell mass and turnover in humans: effects of obesity and aging. Diabetes Care 36:111–117

Samad TA, Moore KA, Sapirstein A, Billet S, Allchorne A, Poole S, Bonventre JV, Woolf CJ (2001) Interleukin-1beta-mediated induction of cox-2 in the CNS contributes to inflammatory pain hypersensitivity. Nature 410:471–475

Sanchez-Alavez M, Klein I, Brownell SE, Tabarean IV, Davis CN, Conti B, Bartfai T (2007) Night eating and obesity in the EP3R-deficient mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:3009–3014

Seaquist ER, Walseth TF, Nelson DM, Robertson RP (1989) Pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein mediation of PGE2 inhibition of cAMP metabolism and phasic glucose-induced insulin secretion in HIT cells. Diabetes 38:1439–1445

Shanmugam N, Todorov IT, Nair I, Omori K, Reddy MA, Natarajan R (2006) Increased expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human pancreatic islets treated with high glucose or ligands of the advanced glycation endproduct-specific receptor (AGER), and in islets from diabetic mice. Diabetologia 49:100–107

Shridas P, Zahoor L, Forrest KJ, Layne JD, Webb NR (2014) Group X secretory phospholipase A2 regulates insulin secretion through a cyclooxygenase-2-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem 289:27410–27417

Sieradzki J, Wolan H, Szczeklik A (1984) Effects of prostacyclin and its stable analog, iloprost, upon insulin secretion in isolated pancreatic islets. Prostaglandins 28:289–296

Sjoholm A (1996) Prostaglandins inhibit pancreatic beta-cell replication and long-term insulin secretion by pertussis toxin-insensitive mechanisms but do not mediate the actions of interleukin-1 beta. Biochim Biophys Acta 1313:106–110

Sjoholm A, Nystrom T (2006) Inflammation and the etiology of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 22:4–10

Sorli CH, Zhang HJ, Armstrong MB, Rajotte RV, Maclouf J, Robertson RP (1998) Basal expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and nuclear factor-interleukin 6 are dominant and coordinately regulated by interleukin 1 in the pancreatic islet. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:1788–1793

Speroff L, Ramwell PW (1970) Prostaglandin stimulation of in vitro progesterone synthesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 30:345–350

Szczeklik A, Pieton R, Sieradzki J, Nizankowski R (1980) The effects of prostacyclin on glycemia and insulin release in man. Prostaglandins 19:959–968

Tadayyon M, Bonney RC, Green IC (1990) Starvation decreases insulin secretion, prostaglandin E2 production and phospholipase A2 activity in rat pancreatic islets. J Endocrinol 124:455–461

Tootle TL (2013) Genetic insights into the in vivo functions of prostaglandin signaling. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 45:1629–1632

Tran PO, Gleason CE, Poitout V, Robertson RP (1999) Prostaglandin E(2) mediates inhibition of insulin secretion by interleukin-1beta. J Biol Chem 274:31245–31248

Tran PO, Gleason CE, Robertson RP (2002) Inhibition of interleukin-1beta-induced COX-2 and EP3 gene expression by sodium salicylate enhances pancreatic islet beta-cell function. Diabetes 51:1772–1778

Vennemann A, Gerstner A, Kern N, Ferreiros Bouzas N, Narumiya S, Maruyama T, Nusing RM (2012) PTGS-2-PTGER2/4 signaling pathway partially protects from diabetogenic toxicity of streptozotocin in mice. Diabetes 61:1879–1887

Wortham M, Sander M (2016) Mechanisms of beta-cell functional adaptation to changes in workload. Diabetes Obes Metab 18(Suppl 1):78–86

Yajima M, Hosoda K, Kanbayashi Y, Nakamura T, Nogimori K, Mizushima Y, Nakase Y, Ui M (1978) Islets-activating protein (IAP) in Bordetella pertussis that potentiates insulin secretory responses of rats. Purification and characterization J Biochem 83:295–303

Yasui M, Tamura Y, Minami M, Higuchi S, Fujikawa R, Ikedo T, Nagata M, Arai H, Murayama T, Yokode M (2015) The prostaglandin E2 receptor EP4 regulates obesity-related inflammation and insulin sensitivity. PLoS One 10:e0136304

Yokoyama U, Iwatsubo K, Umemura M, Fujita T, Ishikawa Y (2013) The prostanoid EP4 receptor and its signaling pathway. Pharmacol Rev 65:1010–1052

Zawalich WS, Zawalich KC, Yamazaki H (2007) Divergent effects of epinephrine and prostaglandin E2 on glucose-induced insulin secretion from perifused rat islets. Metabolism 56:12–18

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank members of the Gannon lab for helpful discussions and, in particular, Dr. Raymond Pasek for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Dr. R. Paul Robertson for reading and helpful discussions of the manuscript. This work was supported by a Merit Award from the Veterans Administration (Grant 1 I01 BX003744-01) to M.G.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carboneau, B.A., Breyer, R.M. & Gannon, M. Regulation of pancreatic β-cell function and mass dynamics by prostaglandin signaling. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 11, 105–116 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12079-017-0377-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12079-017-0377-7