Abstract

Purpose of Review

Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias are the source of significant distress, impairment, and caregiver burden in aging populations. A prominent reason for this impact is the Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD). Common BPSD include disruptive behaviors, such as agitation, aggression, severe anxiety, delusions, depression, apathy, and sleep disturbances. Specific dementias, such as behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies, are associated with socioemotional disturbances and visual hallucinations, respectively. The aim of this review is to present current treatment options for the major BPSD.

Recent Findings

The management of the BPSD requires familiarity with non-pharmacological interventions and skill in the use of pharmacological agents in patients with dementias. This review outlines five important areas of non-pharmacological intervention. It then discusses the use of serotonergic medications, before considering antipsychotic drugs for disruptive behaviors and other BPSD. What is known about psychoactive drug use in cognitively normal populations does not necessarily apply to those with dementia, and the current treatment of patients with dementia emphasizes the need to consider their increased susceptibility to side effects from antipsychotic drugs.

Summary

Effective dementia care requires knowing both non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions for the BPSD, which are present in nearly all patients with dementia at some time in their course. This review presents relatively easily applicable non-pharmacological techniques followed by discussions of the medication options for the major BPSD. In particular, clinicians need to understand current treatment strategies, particularly with regards to psychoactive medications, in this vulnerable population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD) are extremely common, occurring in nearly all patients with dementia [1]. Ever since August Deter, Alois Alzheimer’s original patient who had delusions and other BPSD [2], clinicians have been aware of behavioral disorders in dementia. In addition to greater caregiver distress and burnout [3, 4], BPSD such as agitation, aggression, psychosis, depression, and others significantly impair the ability to care for these patients and thereby accelerate their nursing home placement or institutionalization [5,6,7,8]. The successful management of the BPSD decreases caregiver burden as well as patient distress and is a major focus of the care of patients with dementia [9].

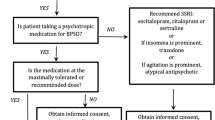

The approach to caring for patients with dementia requires an appreciation of the central role of BPSD in these disorders. BPSD are not just side effects of having a cognitive impairment, but also integral manifestations of dementia and part of the diagnostic criteria for some [10]. Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common dementia, includes changes in personality or behavior [11]; clinical criteria for behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) emphasize behavioral and socioemotional changes [12]; and criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) include visual hallucinations and rapid eye movement behavior disorder (RBD) [13]. While the most common BPSD are apathy and depression, the most impactful in terms of management are the disruptive behaviors of agitation, aggression, and severe anxiety [14]. There is great overlap of these BPSD among the major dementia syndromes, and any one of these symptoms can be experienced in any of the dementias; however, there is a correlation of specific BPSD with individual disorders. Of the major dementias, AD is most likely to result in monothematic delusions, bvFTD in disinhibition and social impropriety, and DLB in visual hallucinations. The treatment of these BPSD, regardless of specific symptom or dementia, starts with non-pharmacological interventions before the consideration of pharmacological agents (see Figure 1).

General non-pharmacological interventions

Non-pharmacologic strategies for the management of the BPDS are preferrable to the use of psychoactive medications, which have a high rate of adverse effects. A meta-analysis of non-pharmacological therapies in AD found that they improved outcomes and quality of life for both patients and caregivers [15], and several studies report that non-pharmacological interventions are more likely to be effective in managing the BPSD than the use of drugs [16,17,18,19]. Although clinical guidelines recommend starting with non-pharmacological measures [20], clinicians frequently fail to apply these interventions, reporting their use in a little over a third of patients in residential care and about a fifth of those in community settings [21•]. Among the many reasons for failure to use non-pharmacological interventions are the time commitment, lack of training, and the ease of resorting to medication use [1].

Non-pharmacological interventions across the dementias can be divided into (1) identifying and eliminating triggers; (2) patient-centered interventions; (3) environment-centered interventions; (4) caregiver-centered interventions; and (5) structured activities. The first step is to identify precipitating factors or situational frustrations recalling that dementia may impair a person’s ability to communicate their irritations, needs, or discomforts. Assess for medical causes of a superimposed delirium including the patient’s medications or dosage changes. Assess for unmet needs, such as hunger, thirst, constipation, and, most importantly, the presence of pain as even mild pain, can aggravate the BPSD. A second step is to develop person-centered care based on knowledge of the individual patient. Formulate a personalized plan including a list of triggers or alleviating factors for the patient’s behavior. Part of this personalized plan is to provide a consistent, regular schedule or routine, including same personnel, mild daily exercise, good sleep hygiene, and maintenance of a day-night cycle.

Other non-pharmacological interventions target the environment and the caregiver. Arrange for a safe, calm, and predictable environment that is quiet, uncluttered, and not overstimulating. Manage the patient’s need for wandering by providing a limited and safe area for ambulation. Also simplify their social environment by limiting unfamiliar contacts and too many people. Proactively anticipate potential problems, avoiding disturbing situations, and foreseeing additional environmental modifications. Attend to the caregiver by offering counseling, support, and educational programs. Caregivers benefit from training in behavioral management techniques such as distraction and redirection, providing reassuring responses, and giving positive reinforcement. Caregivers can learn techniques that they can have ready to use when confronted with a problem. They also benefit from support groups and courses on caring for themselves and managing their stress.

These interventions are enhanced with the inclusion of structured activities [22•, 23, 24]. Engage the patients in their favorite pastimes, hobbies, and other prior comforting activities. One helpful activity is “reminiscence therapy” where the patient views and shares family photos and videos and, with guidance, reminisces on prior experiences and events. In addition to daily light exercise or walking, some patients benefit from more structured exercise programs with consequent decrease in BPSD [25]. A list of other structured therapies includes acupressure, animal or pet, aromatherapy, garden, light, massage, music and dance, occupational and physical therapy, snoezelen multisensory stimulation, touch, multicomponent interventions, and relatively easy cognitive stimulation [1, 26].

Pharmacological treatment

Clinicians frequently revert to pharmacotherapy for management of the BPSD, despite limited indications for their use in dementia. The indications for pharmacotherapy include failure to respond to non-pharmacological interventions, absence of underlying conditions or triggers causing symptoms, and behaviors that cause the patient substantial distress. Antipsychotic medications can be considered if the BPSD represent a danger to themselves or others or significantly interfere with the ability to provide care for them. Unfortunately, many pharmacological agents lack strong evidence from randomized clinical trials (RCTs) confirming their effectiveness, have significant potential side effects, or are used as off-label treatments. Furthermore, their efficacy and safety for the BPSD may be erroneously inferred from their efficacy and safety for primary psychiatric disorders, the so-called fallacy of the “therapeutic metaphor” [10, 27].

A first pharmacological consideration is the role of antidementia drugs, such as the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (ACh-Is) of donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine, along with the novel drug memantine. By enhancing cholinergic function and improving memory or cognitive function, these medications may slightly improve BPSD in some patients. Meta-analysis of studies on the ACh-Is in patients with mild-to-moderate AD has not concluded a significant clinical efficacy on BPSD [28], but they may be helpful in patients with DLB (see the “BPSD in dementia with lewy bodies” section). When compared to other drugs and placebo, donepezil, galantamine, and memantine have the least efficacy for the BPSD [29]. Memantine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist used for moderate-to-severe AD, may diminish disruptive behaviors and other BPSD in individual patients [30, 31], but in the aggregate does not show conclusive efficacy for the BPSD [1]. Even if ACh-Is and memantine mitigate the BPSD, they are not a primary treatment for them [32••].

Disruptive behaviors

The disruptive “A” behaviors — agitation, aggression, and severe anxiety — are the most difficult management challenges of the BPSD. From 44.6 to 74.6% of patients with AD manifest disruptive behaviors [33], evidenced as restlessness, excessive motor active, or verbal or physical aggression. These behaviors frequently occur with hypersensitivity to stimuli, fear of being left alone, sundowning, resistive or reactive aggressive responses to management, or associated delusions. As before, clinicians must first identify personal (e.g., disrupted routine), medical (e.g., pain or polypharmacy with anticholinergic medications), or environmental (e.g., over or under stimulation) precipitants and use non-pharmacological techniques before reverting to psychoactive medications.

An initial pharmacological target in disruptive behaviors associated with dementia is the serotonergic system (see Table 1). Before resorting to antipsychotics, clinicians may consider trazodone (25–100 mg qd), an atypical serotonergic antidepressant, particularly if there is sundowning or nocturnal agitation [32••, 34]. Trazodone is safe if administered in small doses, and it additionally regulates the sleep–wake cycle among patients with AD [35]. A meta-analysis of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) also concluded that citalopram and sertraline were more effective in reducing disruptive behaviors compared to placebo [36], and they may be as effective as the antipsychotic risperidone [37]. An acceptable starting regimen for disruptive behavior is the use of citalopram for at least 9 weeks [38,39,40], but the dose needs to be kept at 20 mg or less because of prolongation of the QT interval and risk for arrhythmias [39].

If the BPSD require escalation of treatment, the judicious use of antipsychotic medications may be indicated, keeping in mind their limited efficacy and potentially serious side effects. Except for pimavanserin for hallucinations and delusions in Parkinson’s disease (PD), antipsychotic drugs are not FDA approved for the treatment of the BPSD [41••]. Unfortunately, these medications are widely prescribed for the BPSD [42,43,44], prompting proposals for limiting their use [45, 46]. Data from 146 randomized trials of 44,873 patients does show modest efficacy in treating BPSD with the antipsychotics risperidone, aripiprazole, haloperidol, and quetiapine compared to placebo [29, 47]; however, the potential adverse effects of these drugs limit their overall usefulness to severe disruptive behaviors and psychosis [48]. The adverse effects include increased mortality in patients with dementia [19, 49,50,51,52,53,54,55], with the risk being dose-dependent but occurring at any time [56]. Report of the mortality risk for dementia patients associated with antipsychotic drugs in the first 180 days of treatment may be 3.8% for haloperidol, 3.7% for risperidone, 2.5% for olanzapine, and 2.0% for quetiapine [57]. The increased mortality is related to a range of interacting factors resulting in strokes, cardiovascular effects, dehydration, venous stasis, extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), metabolic changes, and aspiration with pneumonia [58].

Antipsychotics may be particularly necessary when the risk of harm to self or others is great [59]. Typical antipsychotics with their greater EPS are not recommended except in emergency situations [41••]. Emergency use includes acute intramuscular (IM) administration of 0.25–0.5 mg of the typical antipsychotic haloperidol (intravenous use causes significant QT prolongation) but at not more than 3 mg/day. Randomized clinical trials indicate that haloperidol may help control aggression but not other BPSD [60, 61]. For emergency use, one proposed algorithm recommends IM olanzapine followed by IM haloperidol [2]. In most situations, where there is no acute emergency necessitating IM administration, treatment of severe disruptive behaviors in AD or dementia can use risperidone [34], which has short-term efficacy (6–12 weeks) [53, 62]. In addition to a low starting dose of risperidone (0.25 mg), quetiapine (12.5 mg) and olanzepine (1.25 mg) are alternatives, after informing the patient and family of the increased mortality risk and getting their consent [32••]. When comparing these three drugs, risperidone has highest risk of EPS, olanzepine has metabolic and anticholinergic effects [63, 64], and quetiapine is least effective but has the lowest excess mortality [65]. In some studies, other second-generation antipsychotics, such as aripiprazole, ziprasidone, and clozapine (which requires blood monitoring for agranulocytosis), have shown some efficacy for the BPSD of AD [66,67,68,69]. Once antipsychotic medications are started, they need to be regularly re-evaluated and considered for discontinuation [70, 71]. Although their withdrawal can be done safely [72•, 73], it should be done carefully because of potential consequences, including the obvious risk for relapse of the BPSD [74,75,76].

Investigators have evaluated a range of other drugs for disruptive behaviors in dementia. These include antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) such as divalproex and valproic acid, carbamazepine, gabapentin, and lamotrigine, but they have not shown sufficient efficacy [34, 77, 78]. Valproate preparations appear ineffective for agitation associated with dementia and have a high rate of side effects [77]. Carbamazepine has shown some efficacy [34], but it also has potentially significant side effects. Gabapentin seems to function as a non-specific sedative. One study suggested that lamotrigine may be effective and may make it possible to avoid increasing the dosage of antipsychotic medications for BPSD [78]. Benzodiazepines should be avoided because of possible oversedation or paradoxical agitation, possible physical dependence, and worsening memory. Dextromethorphan-quinidine (a low-affinity N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist) may provide some mild benefit for disruptive behaviors, but it is of uncertain clinical significance [79]. Finally, there is insufficient study to recommend tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) for disruptive behavior in dementia [10, 80].

Psychosis

At least 35% of patients with AD and other dementias develop delusions at some time in their course [14, 81]. Hallucinations also occur, but they are less prominent or disturbing except in DLB. The presence of delusions cause patients and caregivers distress, can lead to disruptive behavior although not invariably, and often results in psychoactive drug use and hospitalizations. In AD, delusions are most commonly monothematic, such as the delusions of theft or of the phantom boarder syndrome, and tend to occur in moderate stages 3 or more years into the disease, but there is also an early “paranoid” reaction in some patients. Non-pharmacological interventions can reduce reactions to delusions among dementia patients and include redirecting the patient, providing reassurance as to their safety, and explaining any misperceptions. There may not be a need to proceed to medications if the false beliefs are not disruptive or overly distressing. For pharmacological intervention, the choice of medications is similar to that for disruptive behaviors with increased emphasis on low-dose antipsychotics. If medications are used, they may need to be escalated to a level where they suppress significant negative reactions to delusions but at a cost of suppression of the patient’s awareness and presence, as well as the risk of other side effects.

Depression

Depression is one of the most common BPSD in AD, vascular dementia (VaD), and PD dementia syndromes. Depression mostly occurs within a few years of dementia onset, ranges from a mild dysthymic state to major depression, and may abate with increasingly severe cognitive deficits. When there is major depression, there are increased hospitalizations and mortality. In otherwise cognitively normal people, late-life depression also increases the risk for developing AD and may predict progression to mild cognitive impairment or AD, particularly within 1 year [82,83,84]. As with all BPSD, the management of clinical depression starts with non-pharmacological interventions and optimization of dementia treatments before proceeding to psychoactive drugs.

Clinicians may treat depression in AD and dementia with SSRIs such as sertraline, citalopram, or escitalopram [85]. Avoid tricyclics because of their anticholinergic effects and worsening of memory function. Despite the widespread use of SSRIs and other antidepressants (30–50% of patient with AD/dementia are on antidepressants), there is mixed evidence regarding the benefits from their use in dementia [86, 87•]. Among patients with depression and AD, the Depression of Alzheimer’s Disease-2 (DIADS2 trial) multicenter trial found no difference between sertraline (100 mg) and placebo [88,89,90]. Yet, SSRIs are widely used, may help some patients with dementia, and are generally safe for use. Preferred second-line agents are serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) such as venlafaxine or duloxetine or antidepressants with a mixed pharmacology (mirtazapine, bupropion). An atypical antipsychotic, or even an AED such as carbamazepine, in small doses may help dementia patients who have disruptive behavior along with depression [63, 91, 92].

Apathy

Like depression, apathy is common in dementia and has a major impact on caregiver and interpersonal relationships [93]. Non-pharmacological management emphasizes providing the “external initiative” for activities by involving patients in pursuits, even if they are passively and not actively engaged. They can be gently guided, not forced, to take part in individual or small-group activities. Drug treatment with ACh-Is, memantine, SSRIs, and antipsychotic medications have demonstrated limited efficacy for treating apathy in AD [94, 95•]. Psychostimulants such as methylphenidate, however, do show some benefit. In the AD Methylphenidate Trial, methylphenidate, which increases concentrations of synaptic dopamine and norepinephrine at receptor sites, reduced apathy in AD when given at 20 mg for 6 weeks [96]. In a 12-week trial of methylphenidate (titrated to 10 mg am and 10 mg noon) in 77 men with mild AD, the medication improved apathy scores as well as depression when compared with placebo [97]. Potential side effects include slight increases in blood pressure and pulse, decreased appetite and weight loss, insomnia, and lowering of the seizure threshold. There is limited data on other related medications such as dextroamphetamine, modafinil, selegiline, pergolide, bromocriptine, and buproprion.

Sleep disorders

Sleep disturbances in patients with dementia include insomnia and nocturnal awakenings, irregular sleep–wake and circadian rhythms, day-night reversals, sundowning, and, in DLB, RBD (see the “BPSD in dementia with lewy bodies” section). Non-pharmacological interventions focus on sleep hygiene techniques particularly keeping patients awake and active during the day and minimizing stimulation in the evening and stimuli at night. Pharmacological interventions start with melatonin (3 mg or more) and low doses of non-benzodiazepine hypnotics (e.g., zolpidem, zopiclone, zaleplon), trazodone, quetiapine, benzodiazepine hypnotics, or ramelteon.

BPSD in frontotemporal dementia

BvFTD usually begins with behavioral or personality change in midlife charactered by apathy/inertia, disinhibition, stereotyped or compulsive/repetitive behavior, carbohydrate craving and dietary changes, and loss of empathy or concern for others [12]. Pharmacological agents have limited efficacy on the BPSD of bvFTD [98••]. An initial caveat is to avoid ACh-Is, which can worsen disinhibition or stereotypical, repetitive behaviors in bvFTD [98••, 99]. There is evidence of impairments in the serotoninergic system in bvFTD [100,101,102], and open-label SSRI studies in FTD have suggested benefits for a number of BPSD [98••, 103–106]. Sertraline has improved behaviors in small open-label trials in bvFTD [107]. In a systematic review of 23 studies on pharmacological interventions for FTD [108•], trazodone reduced the BPSD, and in another RCT of 31 FTD patients, trazodone decreased multiple behavioral symptoms including eating and dietary changes [98••, 109]. Clinicians prefer SSRIs over trazodone for the BPSD in bvFTD because of the sedation, fatigue, dizziness, and other side effects of trazodone at clinical dosages.

There are specific management concerns for individual BPSD such as apathy and disinhibition. In bvFTD, non-pharmacological management of apathy and inertia is similar to that for other dementias and involves caregiver strategies for behavioral redirection and environmental modification [105], and for disinhibition, management involves identifying triggers and gently redirecting or distracting to other activities. There are limited reports of medication trials for apathy in bvFTD. In a single within-subject cross-over study, 8 patients with FTD received a single 40-mg dose of methylphenidate and showed attenuation of risk-taking behavior [110]. Additionally, a small crossover study in bvFTD showed improved apathy and disinhibition with dextroamphetamine (20 mg qd) compared to quetiapine (150 mg qd) [111]. A 6-week open-label trial of citalopram was associated with decreased disinhibition and other BPSD in bvFTD, but citalopram was titrated up to 40 mg qd [112]. Low-dose quetiapine showed some benefit but without clear replication in clinical trials [104]. Valproate for BPSD has not been clearly effective for disinhibition [77]. In bvFTD, there was benefit from lithium (300–1200 mg qd) [113]; however, lithium was associated with an increased falls, in addition to sedation and tremor [113].

Other FTD-spectrum BPDS that often require management are motor repetitive behaviors and eating or dietary changes. In considering intervention for repetitive behaviors, consider whether there is a real need to suppress these behaviors. If they are not dangerous or detrimental, or composed of harmless rituals, they may only require some redirection or substitutions of replacement activities. For changes in eating behavior, caregivers need to monitor and supervise food intake, distract from food with individual activities, and store food in secure and inaccessible containers or locations. Sertraline (50–100 mg qd) significantly decreased verbal and motor stereotypies in an observational trial of 18 patients with bvFTD [114]. Citalopram (20 mg qd) also decreased compulsive-like behaviors in bvFTD [115, 116], but it failed to improve behavior in a follow-up randomized crossover study [117]. SSRIs and trazodone are also the main drugs for eating or dietary behaviors. In one RCT of 31 FTD patients, trazodone decreased multiple behavioral symptoms including eating and dietary changes [98••, 109]. Additionally, topiramate (100–150 mg qd) has been helpful in suppressing compulsive eating and drinking behaviors in a number of case studies [118,119,120,121]. Other drugs tried in these BPSD with limited success include paroxetine, clomipramine, buspirone, depakote, and dextromethorphan/guinidine.

The management of inappropriate sexual behavior starts with a range of non-pharmacological strategies. As with all behaviors, remain calm, patient, and non-judgmental. Remove precipitating factors or visual triggers, use distraction and diversional activities, and provide a safe place for their private sexual expression. There is limited efficacy reducing inappropriate sexual behavior with SSRIs, AEDs, antipsychotic agents, ACh-Is, pindolol, and cimetidine [122,123,124,125]. SSRIs induce hyposexuality, which may be a desired side effect in patients with bvFTD [104]. Case reports suggest that AEDs such valproate and carbamazepine can be helpful in suppressing indiscriminate and inappropriate sexual behavior [104, 126, 127]. Other drugs are not first-line because of potential side effects including antiandrogens, non-hormonal drugs with antiandrogen effects, gonadotropin releasing hormonal analogues such as leuprolide, and other hormonal agents such as estrogen and diethylstilbestrol.

Finally, a major source of anguish for caregivers and family is the loss of empathy and the indifference and lack of emotional warmth that they experience from patients with bvFTD. Caregivers must work at rethinking expectation of emotional feedback and not expecting reciprocity or validation of their overtures. They can also provide the patient direct information about their perspective, and that of others, and share with them moments of connection or shared special events. There are no specifically effective drugs for this major BPSD of bvFTD, although SSRIs can help. The exception may be oxytocin, a neuropeptide implicated in human social behavior and cognition. Intranasal oxytocin (24–72 IU twice daily) has improved empathy and patient-caregiver interactions, when compared with placebo and is safe and well-tolerated [128, 129].

BPSD in dementia with lewy bodies

The presence of visual hallucinations early in the course of dementia strongly predicts DLB. The prevalence of visual hallucinations varies across different dementias with estimates of 55 to 78% in DLB, 32 to 63% in the related PD dementia, 11 to 17% in AD, and 5 to 14% in VaD [130]. Visual hallucinations in DLB are either well-formed images of people, children, and animals or they are vaguer sensations of “passage” (consisting of movement or being briefly seen in the periphery), sense of presence (peripheral shadows or emerging human-like shapes; “pareidolias”), or visual illusions or misperceptions [81, 131]. Patient reactions to these visual phenomena vary depending on degree of insight and emotion response. Around 50% of patients are significantly distressed by their visual phenomena [131].

The management of hallucinations starts with a thorough eye examination and the correction of any source of visual impairment such as cataracts. Non-pharmacological management includes reassurance and altering the environment particularly with better lighting during the day, directing attention away from hallucinations, and encouraging their acceptance as mental events. Where possible, decrease the dose of dopaminergic medications, such as levodopa/carbidopa. Treat with medications only if they are upsetting to the patient. A threshold for intervention is when transitioning from full insight (“pseudohallucinations”) to partial or fluctuating insight, where the patient responds to visual hallucinations as if they were real [131]. Patients with DLB may have a decrease in visual hallucinations with ACh-Is and should be initially started on donepezil or rivastigmine [132]. A study of memantine also found reduced hallucinations in DLB after 24-week treatment [133].

Although atypical antipsychotics have been used safety and efficaciously in DLB [134, 135], these medications are particularly problematic in this disorder due to a heightened sensitivity to their effects, and even an increased risk of the neuroleptic malignant syndrome. When pharmacotherapy is necessary, only use very low doses of certain atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine. Pimavanserin, an inverse agonist of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, is approved for the treatment of hallucinations and delusions in the psychosis of PD and may also have efficacy in DLB since these are related conditions [136•]. Similar to other antipsychotics in dementia, pimavanserin has a black box warning and is associated QT prolongation, peripheral edema, and confusion. Finally, RBD disorder, another BPSD of DLB, is managed with melatonin and, if ineffective, small doses of clonazepam (e.g., 0.25 mg) [13].

Conclusions

The BPSD are integral manifestations of dementia and have a major negative impact in the care of these patients. The BPSD can respond to non-pharmacological interventions and judicious pharmacological therapy. Start with non-pharmacological interventions: identify and remove triggers and apply patient-centered techniques, environmental changes, caregiver-centered techniques, and engage patients in specific activities. Use pharmacological agents only when symptoms have not responded to non-pharmacological means and are distressing to the patient. Antipsychotic medications may be indicated when the BPSD are potentially harmful to self or others or seriously prevent the provision of care to the patient. Clinicians need skill and expertise in the use of psychoactive drugs to target disruptive behaviors, psychosis, depression, apathy, sleep disorders, and other behavioral symptoms that may be more prevalent in specific dementias. BvFTD and DLB have special considerations on minimizing the use of ACh-Is and antipsychotic drugs, respectively. In addition to maximizing dementia medications were indicated, there are a number of agents, such as SSRIs and trazodone, that can be tried before resorting to the atypical antipsychotics, which have a black box warning for increased morbidity and mortality. If there is a need to use antipsychotics, aim for the lowest dose and for the shortest treatment duration. There is much ongoing research in this important field, with newer, as well as older, interventions and medications undergoing evaluation or repurposing for the management of the BPSD. With this ongoing research, the interventions and recommendations presented her are likely to evolve in the coming years.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Magierski R, Sobow T, Schwertner E, Religa D. Pharmacotherapy of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: state of the art and future progress. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1168. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.01168.

Chen A, Copeli F, Metzger E, Cloutier A, Osser DN. The psychopharmacology algorithm project at the Harvard South Shore Program: an update on management of behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295: 113641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113641.

Ornstein K, Gaugler JE. The problem with “problem behaviors”: a systematic review of the association between individual patient behavioral and psychological symptoms and caregiver depression and burden within the dementia patient-caregiver dyad. Int Psychogeriatrics / IPA. 2012;24(10):1536–52. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610212000737.

Hiyoshi-Taniguchi K, Becker CB, Kinoshita A. What behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia affect caregiver burnout? Clin Gerontol. 2018;41(3):249–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2017.1398797.

Gaugler JE, Yu F, Krichbaum K, Wyman JF. Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Med Care. 2009;47(2):191–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818457ce.

Feast A, Moniz-Cook E, Stoner C, Charlesworth G, Orrell M. A systematic review of the relationship between behavioral and psychological symptoms (BPSD) and caregiver well-being. Int Psychogeriatrics / IPA. 2016;28(11):1761–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216000922.

Terum TM, Andersen JR, Rongve A, Aarsland D, Svendsboe EJ, Testad I. The relationship of specific items on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory to caregiver burden in dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(7):703–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4704.

Vandepitte S, Putman K, Van Den Noortgate N, Verhaeghe S, Mormont E, Van Wilder L, De Smedt D, Annemans L. Factors associated with the caregivers’ desire to institutionalize persons with dementia: a cross-sectional study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2018;46(5–6):298–309. https://doi.org/10.1159/000494023.

Kameoka N, Sumitani S, Ohmori T. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and care burden: examination in the facility staff for elderly residents. J Med Invest. 2020;67(3.4):236–239. https://doi.org/10.2152/jmi.67.236.

Cummings J, Ritter A, Rothenberg K. Advances in management of neuropsychiatric syndromes in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(8):79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1058-4.

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005.

Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, Mendez MF, Kramer JH, Neuhaus J, van Swieten JC, Seelaar H, Dopper EG, Onyike CU, Hillis AE, Josephs KA, Boeve BF, Kertesz A, Seeley WW, Rankin KP, Johnson JK, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rosen H, Prioleau-Latham CE, Lee A, Kipps CM, Lillo P, Piguet O, Rohrer JD, Rossor MN, Warren JD, Fox NC, Galasko D, Salmon DP, Black SE, Mesulam M, Weintraub S, Dickerson BC, Diehl-Schmid J, Pasquier F, Deramecourt V, Lebert F, Pijnenburg Y, Chow TW, Manes F, Grafman J, Cappa SF, Freedman M, Grossman M, Miller BL. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 9):2456–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr179.

McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Halliday G, Taylor JP, Weintraub D, Aarsland D, Galvin J, Attems J, Ballard CG, Bayston A, Beach TG, Blanc F, Bohnen N, Bonanni L, Bras J, Brundin P, Burn D, Chen-Plotkin A, Duda JE, El-Agnaf O, Feldman H, Ferman TJ, Ffytche D, Fujishiro H, Galasko D, Goldman JG, Gomperts SN, Graff-Radford NR, Honig LS, Iranzo A, Kantarci K, Kaufer D, Kukull W, Lee VMY, Leverenz JB, Lewis S, Lippa C, Lunde A, Masellis M, Masliah E, McLean P, Mollenhauer B, Montine TJ, Moreno E, Mori E, Murray M, O’Brien JT, Orimo S, Postuma RB, Ramaswamy S, Ross OA, Salmon DP, Singleton A, Taylor A, Thomas A, Tiraboschi P, Toledo JB, Trojanowski JQ, Tsuang D, Walker Z, Yamada M, Kosaka K. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89(1):88–100. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058.

Zhao QF, Tan L, Wang HF, Jiang T, Tan MS, Tan L, Xu W, Li JQ, Wang J, Lai TJ, Yu JT. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:264–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.069.

Olazaran J, Reisberg B, Clare L, Cruz I, Pena-Casanova J, Del Ser T, Woods B, Beck C, Auer S, Lai C, Spector A, Fazio S, Bond J, Kivipelto M, Brodaty H, Rojo JM, Collins H, Teri L, Mittelman M, Orrell M, Feldman HH, Muniz R. Nonpharmacological therapies in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review of efficacy. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;30(2):161–78. https://doi.org/10.1159/000316119.

Ayalon L, Gum AM, Feliciano L, Arean PA. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions for the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(20):2182–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.20.2182.

Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):946–53. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101529.

Yury CA, Fisher JE. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of behavioural problems in persons with dementia. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76(4):213–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000101499.

Schneider LS, Dagerman K, Insel PS. Efficacy and adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(3):191–210. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JGP.0000200589.01396.6d.

Dyer SM, Harrison SL, Laver K, Whitehead C, Crotty M. An overview of systematic reviews of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Psychogeriatrics / IPA. 2018;30(3):295–309. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217002344.

• Aigbogun MS, Cloutier M, Gauthier-Loiselle M, Guerin A, Ladouceur M, Baker RA, Grundman M, Duffy RA, Hartry A, Gwin K, Fillit H. Real-world treatment patterns and characteristics among patients with agitation and dementia in the United States: findings from a large, observational, retrospective chart review. J Alzheimers Dis 2020;77(3):1181–1194. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200127. This is an important review of the issues and difficulties in implementing nonpharmacological interventions without quickly resorting the medications for the BPSD.

• Watt JA, Goodarzi Z, Veroniki AA, Nincic V, Khan PA, Ghassemi M, Thompson Y, Tricco AC, Straus SE. Comparative efficacy of interventions for aggressive and agitated behaviors in dementia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(9):633–642. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-0993. The authors discuss non-pharmacological interventions for disruptive behaviors in comparison to other interventions.

Leng M, Zhao Y, Wang Z. Comparative efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions on agitation in people with dementia: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;102: 103489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103489.

Tonga JB, Saltyte Benth J, Arnevik EA, Werheid K, Korsnes MS, Ulstein ID. Managing depressive symptoms in people with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia with a multicomponent psychotherapy intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Int Psychogeriatrics / IPA. 2021;33(3):217–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220000216.

Rodrigues S, Silva JMD, Oliveira MCC, Santana CMF, Carvalho KM, Barbosa B. Physical exercise as a non-pharmacological strategy for reducing behavioral and psychological symptoms in elderly with mild cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2021;79(12):1129–37. https://doi.org/10.1590/0004-282X-ANP-2020-0539.

Garcia-Alberca JM. Cognitive intervention therapy as treatment for behaviour disorders in Alzheimer disease: evidence on efficacy and neurobiological correlations. Neurologia (Barcelona, Spain). 2015;30(1):8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrl.2012.10.002.

Tariot PN. Treatment strategies for agitation and psychosis in dementia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(Suppl 14):21–9.

Kobayashi H, Ohnishi T, Nakagawa R, Yoshizawa K. The comparative efficacy and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(8):892–904. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4405.

Jin B, Liu H. Comparative efficacy and safety of therapy for the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a systemic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2019;266(10):2363–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09200-8.

Cummings JL, Schneider E, Tariot PN, Graham SM, Memantine MEMMDSG. Behavioral effects of memantine in Alzheimer disease patients receiving donepezil treatment. Neurology. 2006;67(1):57–63. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000223333.42368.f1.

Wilcock GK, Ballard CG, Cooper JA, Loft H. Memantine for agitation/aggression and psychosis in moderately severe to severe Alzheimer’s disease: a pooled analysis of 3 studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(3):341–8. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v69n0302.

•• Ringman JM, Schneider L. Treatment options for agitation in dementia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2019;21:7–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-019-0572-3. This review is an exceptional discussion of current treatment options for agitation and related disruptive behavior in patients with dementia. It includes discussion of the potential problems in reverting to antipsychotic medications without considering other medications.

Halpern R, Seare J, Tong J, Hartry A, Olaoye A, Aigbogun MS. Using electronic health records to estimate the prevalence of agitation in Alzheimer disease/dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(3):420–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5030.

Davies SJ, Burhan AM, Kim D, Gerretsen P, Graff-Guerrero A, Woo VL, Kumar S, Colman S, Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Rajji TK. Sequential drug treatment algorithm for agitation and aggression in Alzheimer’s and mixed dementia. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(5):509–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881117744996.

Grippe TC, Goncalves BS, Louzada LL, Quintas JL, Naves JO, Camargos EF, Nobrega OT. Circadian rhythm in Alzheimer disease after trazodone use. Chronobiol Int. 2015;32(9):1311–4. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2015.1077855.

Seitz DP, Adunuri N, Gill SS, Gruneir A, Herrmann N, Rochon P. Antidepressants for agitation and psychosis in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(2):CD008191. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008191.pub2.

Viscogliosi G, Chiriac IM, Ettorre E. Efficacy and safety of citalopram compared to atypical antipsychotics on agitation in nursing home residents with Alzheimer dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(9):799–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.06.010.

Porsteinsson AP, Antonsdottir IM. An update on the advancements in the treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18(6):611–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2017.1307340.

Porsteinsson AP, Drye LT, Pollock BG, Devanand DP, Frangakis C, Ismail Z, Marano C, Meinert CL, Mintzer JE, Munro CA, Pelton G, Rabins PV, Rosenberg PB, Schneider LS, Shade DM, Weintraub D, Yesavage J, Lyketsos CG, Cit ADRG. Effect of citalopram on agitation in Alzheimer disease: the CitAD randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(7):682–91. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.93.

Weintraub D, Drye LT, Porsteinsson AP, Rosenberg PB, Pollock BG, Devanand DP, Frangakis C, Ismail Z, Marano C, Meinert CL, Mintzer JE, Munro CA, Pelton G, Rabins PV, Schneider LS, Shade DM, Yesavage J, Lyketsos CG, Cit ADRG. Time to response to citalopram treatment for agitation in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(11):1127–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2015.05.006.

•• Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Eyler AE, Hilty DM, Horvitz-Lennon M, Jibson MD, Lopez OL, Mahoney J, Pasic J, Tan ZS, Wills CD, Rhoads R, Yager J. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline on the use of antipsychotics to treat agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(5):543–546. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.173501. The authors provide guidance and guidelines for considering the use of antipsychotic medications for agitation and psychosis in those with dementia.

Desai VC, Heaton PC, Kelton CM. Impact of the Food and Drug Administration’s antipsychotic black box warning on psychotropic drug prescribing in elderly patients with dementia in outpatient and office-based settings. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(5):453–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.08.004.

Norgaard A, Jensen-Dahm C, Gasse C, Hansen HV, Waldemar G. Time trends in antipsychotic drug use in patients with dementia: a nationwide study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49(1):211–20. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150481.

Rios S, Perlman CM, Costa A, Heckman G, Hirdes JP, Mitchell L. Antipsychotics and dementia in Canada: a retrospective cross-sectional study of four health sectors. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):244. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0636-8.

Jessop T, Harrison F, Cations M, Draper B, Chenoweth L, Hilmer S, Westbury J, Low LF, Heffernan M, Sachdev P, Close J, Blennerhassett J, Marinkovich M, Shell A, Brodaty H. Halting Antipsychotic Use in Long-Term care (HALT): a single-arm longitudinal study aiming to reduce inappropriate antipsychotic use in long-term care residents with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Psychogeriatrics / IPA. 2017;29(8):1391–403. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217000084.

Kirkham J, Sherman C, Velkers C, Maxwell C, Gill S, Rochon P, Seitz D. Antipsychotic use in dementia. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(3):170–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743716673321.

Seitz DP, Gill SS, Herrmann N, Brisbin S, Rapoport MJ, Rines J, Wilson K, Le Clair K, Conn DK. Pharmacological treatments for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in long-term care: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatrics / IPA. 2013;25(2):185–203. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610212001627.

Yunusa I, Alsumali A, Garba AE, Regestein QR, Eguale T. Assessment of reported comparative effectiveness and safety of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3): e190828. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0828.

Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294(15):1934–43. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.15.1934.

Kales HC, Kim HM, Zivin K, Valenstein M, Seyfried LS, Chiang C, Cunningham F, Schneider LS, Blow FC. Risk of mortality among individual antipsychotics in patients with dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):71–9. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030347.

Ma H, Huang Y, Cong Z, Wang Y, Jiang W, Gao S, Zhu G. The efficacy and safety of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of dementia: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(3):915–37. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-140579.

Ralph SJ, Espinet AJ. Increased all-cause mortality by antipsychotic drugs: updated review and meta-analysis in dementia and general mental health care. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2018;2(1):1–26. https://doi.org/10.3233/ADR-170042.

Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, Davis SM, Hsiao JK, Ismail MS, Lebowitz BD, Lyketsos CG, Ryan JM, Stroup TS, Sultzer DL, Weintraub D, Lieberman JA, Group C-AS. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1525–38. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa061240.

Ismail MS, Dagerman K, Tariot PN, Abbott S, Kavanagh S, Schneider LS. National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness-Alzheimer’s Disease (CATIE-AD): baseline characteristics. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4(3):325–35. https://doi.org/10.2174/156720507781077214.

Sultzer DL, Davis SM, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, Lebowitz BD, Lyketsos CG, Rosenheck RA, Hsiao JK, Lieberman JA, Schneider LS, Group C-AS. Clinical symptom responses to atypical antipsychotic medications in Alzheimer’s disease: phase 1 outcomes from the CATIE-AD effectiveness trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):844–54. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111779.

Maust DT, Kim HM, Seyfried LS, Chiang C, Kavanagh J, Schneider LS, Kales HC. Antipsychotics, other psychotropics, and the risk of death in patients with dementia: number needed to harm. JAMA Psychiat. 2015;72(5):438–45. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3018.

Rochon PA, Normand SL, Gomes T, Gill SS, Anderson GM, Melo M, Sykora K, Lipscombe L, Bell CM, Gurwitz JH. Antipsychotic therapy and short-term serious events in older adults with dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(10):1090–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.168.10.1090.

Steinberg M, Lyketsos CG. Atypical antipsychotic use in patients with dementia: managing safety concerns. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):900–6. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030342.

Van der Spek K, Gerritsen DL, Smalbrugge M, Nelissen-Vrancken MH, Wetzels RB, Smeets CH, Zuidema SU, Koopmans RT. Only 10% of the psychotropic drug use for neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia is fully appropriate. The Proper I-study. Int Psychogeriatrics / IPA. 2016;28(10):1589–1595. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104161021600082X.

Kongpakwattana K, Sawangjit R, Tawankanjanachot I, Bell JS, Hilmer SN, Chaiyakunapruk N. Pharmacological treatments for alleviating agitation in dementia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(7):1445–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.13604.

Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Colford J. Haloperidol for agitation in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD002852. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002852.

Katz I, de Deyn PP, Mintzer J, Greenspan A, Zhu Y, Brodaty H. The efficacy and safety of risperidone in the treatment of psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease and mixed dementia: a meta-analysis of 4 placebo-controlled clinical trials. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(5):475–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1792.

Street JS, Clark WS, Gannon KS, Cummings JL, Bymaster FP, Tamura RN, Mitan SJ, Kadam DL, Sanger TM, Feldman PD, Tollefson GD, Breier A. Olanzapine treatment of psychotic and behavioral symptoms in patients with Alzheimer disease in nursing care facilities: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. The HGEU Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(10):968–976. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.968.

Mulsant BH, Gharabawi GM, Bossie CA, Mao L, Martinez RA, Tune LE, Greenspan AJ, Bastean JN, Pollock BG. Correlates of anticholinergic activity in patients with dementia and psychosis treated with risperidone or olanzapine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(12):1708–14. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v65n1217.

Lanctot KL, Amatniek J, Ancoli-Israel S, Arnold SE, Ballard C, Cohen-Mansfield J, Ismail Z, Lyketsos C, Miller DS, Musiek E, Osorio RS, Rosenberg PB, Satlin A, Steffens D, Tariot P, Bain LJ, Carrillo MC, Hendrix JA, Jurgens H, Boot B. Neuropsychiatric signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease: new treatment paradigms. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2017;3(3):440–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trci.2017.07.001.

De Deyn PP, Katz IR, Brodaty H, Lyons B, Greenspan A, Burns A. Management of agitation, aggression, and psychosis associated with dementia: a pooled analysis including three randomized, placebo-controlled double-blind trials in nursing home residents treated with risperidone. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2005;107(6):497–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2005.03.013.

Rocha FL, Hara C, Ramos MG, Kascher GG, Santos MA, de Oliveira LG, Magalhaes Scoralick F. An exploratory open-label trial of ziprasidone for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(5–6):445–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000095804.

Mintzer JE, Tune LE, Breder CD, Swanink R, Marcus RN, McQuade RD, Forbes A. Aripiprazole for the treatment of psychoses in institutionalized patients with Alzheimer dementia: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled assessment of three fixed doses. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(11):918–31. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181557b47.

Streim JE, Porsteinsson AP, Breder CD, Swanink R, Marcus R, McQuade R, Carson WH. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of aripiprazole for the treatment of psychosis in nursing home patients with Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(7):537–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e318165db77.

Azermai M, Petrovic M, Engelborghs S, Elseviers MM, Van der Mussele S, Debruyne H, Van Bortel L, Vander Stichele RH. The effects of abrupt antipsychotic discontinuation in cognitively impaired older persons: a pilot study. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17(1):125–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2012.717255.

Miarons M, Cabib C, Baron FJ, Rofes L. Evidence and decision algorithm for the withdrawal of antipsychotic treatment in the elderly with dementia and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(11):1389–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-017-2314-3.

• Gedde MH, Husebo BS, Mannseth J, Kjome RLS, Naik M, Berge LI. Less is more: the impact of deprescribing psychotropic drugs on behavioral and psychological symptoms and daily functioning in nursing home patients. Results From the Cluster-Randomized Controlled COSMOS Trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(3):304–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.07.004. This article is a good review and discussion of the issue of withdrawing medications used for the BPSD and of how to approach this issue.

Declercq T, Petrovic M, Azermai M, Vander Stichele R, De Sutter AI, van Driel ML, Christiaens T. Withdrawal versus continuation of chronic antipsychotic drugs for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2013;(3):CD007726. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007726.pub2.

Gao RL, Lim KS, Luthra AS. Discontinuation of antipsychotics treatment for elderly patients within a specialized behavioural unit: a retrospective review. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021;43(1):212–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-020-01135-9.

Van Leeuwen E, Petrovic M, van Driel ML, De Sutter AI, Vander Stichele R, Declercq T, Christiaens T. Withdrawal versus continuation of long-term antipsychotic drug use for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3:CD007726. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007726.pub3.

Devanand DP, Mintzer J, Schultz SK, Andrews HF, Sultzer DL, de la Pena D, Gupta S, Colon S, Schimming C, Pelton GH, Levin B. Relapse risk after discontinuation of risperidone in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(16):1497–507. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1114058.

Baillon SF, Narayana U, Luxenberg JS, Clifton AV. Valproate preparations for agitation in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:CD003945. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003945.pub4.

Suzuki H, Gen K. Clinical efficacy of lamotrigine and changes in the dosages of concomitantly used psychotropic drugs in Alzheimer’s disease with behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: a preliminary open-label trial. Psychogeriatrics : Official J Japanese Psychogeriatric Soc. 2015;15(1):32–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12085.

Cummings JL, Lyketsos CG, Peskind ER, Porsteinsson AP, Mintzer JE, Scharre DW, De La Gandara JE, Agronin M, Davis CS, Nguyen U, Shin P, Tariot PN, Siffert J. Effect of dextromethorphan-quinidine on agitation in patients with Alzheimer disease dementia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(12):1242–54. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10214.

van den Elsen GA, Ahmed AI, Verkes RJ, Kramers C, Feuth T, Rosenberg PB, van der Marck MA, Olde Rikkert MG. Tetrahydrocannabinol for neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2015;84(23):2338–46. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001675.

Naasan G, Shdo SM, Rodriguez EM, Spina S, Grinberg L, Lopez L, Karydas A, Seeley WW, Miller BL, Rankin KP. Psychosis in neurodegenerative disease: differential patterns of hallucination and delusion symptoms. Brain. 2021;144(3):999–1012. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaa413.

Brommelhoff JA, Gatz M, Johansson B, McArdle JJ, Fratiglioni L, Pedersen NL. Depression as a risk factor or prodromal feature for dementia? Findings in a population-based sample of Swedish twins. Psychol Aging. 2009;24(2):373–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015713.

Li G, Wang LY, Shofer JB, Thompson ML, Peskind ER, McCormick W, Bowen JD, Crane PK, Larson EB. Temporal relationship between depression and dementia: findings from a large community-based 15-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(9):970–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.86.

Mirza SS, Wolters FJ, Swanson SA, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Tiemeier H, Ikram MA. 10-year trajectories of depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: a population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(7):628–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00097-3.

Magierski R, Sobow T. Serotonergic drugs for the treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2016;16(4):375–87. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.2016.1155453.

Sepehry AA, Lee PE, Hsiung GY, Beattie BL, Jacova C. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease with comorbid depression: a meta-analysis of depression and cognitive outcomes. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(10):793–806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-012-0012-5.

• Dudas R, Malouf R, McCleery J, Dening T. Antidepressants for treating depression in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;8:CD003944. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003944.pub2. This Cochrane review focuses on the use of SSRI and other antidepressants for the treatment of depression among those with dementia.

Martin BK, Frangakis CE, Rosenberg PB, Mintzer JE, Katz IR, Porsteinsson AP, Schneider LS, Rabins PV, Munro CA, Meinert CL, Niederehe G, Lyketsos CG. Design of depression in Alzheimer’s Disease study-2. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):920–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JGP.0000240977.71305.ee.

Rosenberg PB, Drye LT, Martin BK, Frangakis C, Mintzer JE, Weintraub D, Porsteinsson AP, Schneider LS, Rabins PV, Munro CA, Meinert CL, Lyketsos CG, Group D-R. Sertraline for the treatment of depression in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):136–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181c796eb.

Weintraub D, Rosenberg PB, Drye LT, Martin BK, Frangakis C, Mintzer JE, Porsteinsson AP, Schneider LS, Rabins PV, Munro CA, Meinert CL, Lyketsos CG, Group D-R. Sertraline for the treatment of depression in Alzheimer disease: week-24 outcomes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(4):332–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cc0333.

Katz IR. Depression in late life: psychiatric-medical comorbidity. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 1999;1(2):81–94.

Tariot PN, Erb R, Podgorski CA, Cox C, Patel S, Jakimovich L, Irvine C. Efficacy and tolerability of carbamazepine for agitation and aggression in dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(1):54–61. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.155.1.54.

de Vugt ME, Stevens F, Aalten P, Lousberg R, Jaspers N, Winkens I, Jolles J, Verhey FR. Behavioural disturbances in dementia patients and quality of the marital relationship. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(2):149–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.807.

Sepehry AA, Sarai M, Hsiung GR. Pharmacological therapy for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2017;44(3):267–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2016.426.

• Ruthirakuhan MT, Herrmann N, Abraham EH, Chan S, Lanctot KL. Pharmacological interventions for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD012197. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012197.pub2. The authors present one of the best recent reviews of medications used to treat apathy among patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Rosenberg PB, Lanctot KL, Drye LT, Herrmann N, Scherer RW, Bachman DL, Mintzer JE, Investigators A. Safety and efficacy of methylphenidate for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(8):810–6. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12m08099.

Padala PR, Padala KP, Lensing SY, Ramirez D, Monga V, Bopp MM, Roberson PK, Dennis RA, Petty F, Sullivan DH, Burke WJ. Methylphenidate for apathy in community-dwelling older veterans with mild Alzheimer’s disease: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(2):159–68. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17030316.

•• Khoury R, Liu Y, Sheheryar Q, Grossberg GT. Pharmacotherapy for frontotemporal dementia. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(4):425–438 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-021-00813-0. This paper is a highly informative and well-organized review of the drug treatments available for the particular BPSD from bvFTD and related syndromes.

Mendez MF, Shapira JS, McMurtray A, Licht E. Preliminary findings: behavioral worsening on donepezil in patients with frontotemporal dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(1):84–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JGP.0000231744.69631.33.

Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, Ganjavi H, Black SE, Rusjan PM, Houle S, Wilson AA. Serotonin-1A receptors in frontotemporal dementia compared with controls. Psychiatry Res. 2007;156(3):247–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.07.003.

Procter AW, Qurne M, Francis PT. Neurochemical features of frontotemporal dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10(Suppl 1):80–4. https://doi.org/10.1159/000051219.

Yang Y, Schmitt HP. Frontotemporal dementia: evidence for impairment of ascending serotoninergic but not noradrenergic innervation. Immunocytochemical and quantitative study using a graph method. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;101(3):256–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004010000293.

Swartz JR, Miller BL, Lesser IM, Darby AL. Frontotemporal dementia: treatment response to serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(5):212–6.

Chow TW, Mendez MF. Goals in symptomatic pharmacologic management of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2002;17(5):267–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/153331750201700504.

Ljubenkov PA, Boxer AL. FTLD treatment: current practice and future possibilities. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1281:297–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51140-1_18.

Huey ED, Putnam KT, Grafman J. A systematic review of neurotransmitter deficits and treatments in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2006;66(1):17–22. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000191304.55196.4d.

Prodan CI, Monnot M, Ross ED. Behavioural abnormalities associated with rapid deterioration of language functions in semantic dementia respond to sertraline. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(12):1416–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2009.173260.

• Trieu C, Gossink F, Stek ML, Scheltens P, Pijnenburg YAL, Dols A. Effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for symptoms of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2020;33(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNN.0000000000000217. The authors review the current knowledge of pharmacological interventions for the BPDS of bvFTD.

Lebert F, Stekke W, Hasenbroekx C, Pasquier F. Frontotemporal dementia: a randomised, controlled trial with trazodone. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(4):355–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000077171.

Rahman S, Robbins TW, Hodges JR, Mehta MA, Nestor PJ, Clark L, Sahakian BJ. Methylphenidate (‘Ritalin’) can ameliorate abnormal risk-taking behavior in the frontal variant of frontotemporal dementia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(3):651–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300886.

Huey ED, Garcia C, Wassermann EM, Tierney MC, Grafman J. Stimulant treatment of frontotemporal dementia in 8 patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(12):1981–2. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v69n1219a.

Hermann M, Waade RB, Molden E. Therapeutic drug monitoring of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in elderly patients. Ther Drug Monit. 2015;37(4):546–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/FTD.0000000000000169.

Devanand DP, Pelton GH, D’Antonio K, Strickler JG, Kreisl WC, Noble J, Marder K, Skomorowsky A, Huey ED. Low-dose lithium treatment for agitation and psychosis in Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal dementia: a case series. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2017;31(1):73–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0000000000000161.

Mendez MF, Shapira JS, Miller BL. Stereotypical movements and frontotemporal dementia. Mov Disord. 2005;20(6):742–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.20465.

Meyer S, Mueller K, Gruenewald C, Grundl K, Marschhauser A, Tiepolt S, Barthel H, Sabri O, Schroeter ML. Citalopram improves obsessive-compulsive crossword puzzling in frontotemporal dementia. Case Rep Neurol. 2019;11(1):94–105. https://doi.org/10.1159/000495561.

Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, Cazzato G, Bava A. Frontotemporal dementia: paroxetine as a possible treatment of behavior symptoms. A randomized, controlled, open 14-month study. Eur Neurol. 2003;49(1):13–19. https://doi.org/10.1159/000067021.

Deakin JB, Rahman S, Nestor PJ, Hodges JR, Sahakian BJ. Paroxetine does not improve symptoms and impairs cognition in frontotemporal dementia: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Psychopharmacology. 2004;172(4):400–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-003-1686-5.

Cruz M, Marinho V, Fontenelle LF, Engelhardt E, Laks J. Topiramate may modulate alcohol abuse but not other compulsive behaviors in frontotemporal dementia: case report. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2008;21(2):104–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNN.0b013e31816bdf73.

Nestor PJ. Reversal of abnormal eating and drinking behaviour in a frontotemporal lobar degeneration patient using low-dose topiramate. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(3):349–50. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2010.238899.

Singam C, Walterfang M, Mocellin R, Evans A, Velakoulis D. Topiramate for abnormal eating behaviour in frontotemporal dementia. Behav Neurol. 2013;27(3):285–6. https://doi.org/10.3233/BEN-120257.

Shinagawa S, Tsuno N, Nakayama K. Managing abnormal eating behaviours in frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients with topiramate. Psychogeriatrics : Official J Japanese Psychogeriatric Soc. 2013;13(1):58–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-8301.2012.00429.x.

Anneser JM, Jox RJ, Borasio GD. Inappropriate sexual behaviour in a case of ALS and FTD: successful treatment with sertraline. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2007;8(3):189–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482960601073543.

Black B, Muralee S, Tampi RR. Inappropriate sexual behaviors in dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18(3):155–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988705277541.

Guay DR. Inappropriate sexual behaviors in cognitively impaired older individuals. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2008;6(5):269–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjopharm.2008.12.004.

Light SA, Holroyd S. The use of medroxyprogesterone acetate for the treatment of sexually inappropriate behaviour in patients with dementia. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006;31(2):132–4.

Poetter CE, Stewart JT. Treatment of indiscriminate, inappropriate sexual behavior in frontotemporal dementia with carbamazepine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(1):137–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e31823f91b9.

Galvez-Andres A, Blasco-Fontecilla H, Gonzalez-Parra S, Molina JD, Padin JM, Rodriguez RH. Secondary bipolar disorder and Diogenes syndrome in frontotemporal dementia: behavioral improvement with quetiapine and sodium valproate. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):722–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e31815a57c1.

Jesso S, Morlog D, Ross S, Pell MD, Pasternak SH, Mitchell DG, Kertesz A, Finger EC. The effects of oxytocin on social cognition and behaviour in frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 9):2493–501. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr171.

Finger EC, MacKinley J, Blair M, Oliver LD, Jesso S, Tartaglia MC, Borrie M, Wells J, Dziobek I, Pasternak S, Mitchell DG, Rankin K, Kertesz A, Boxer A. Oxytocin for frontotemporal dementia: a randomized dose-finding study of safety and tolerability. Neurology. 2015;84(2):174–81. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001133.

Cummings JL, Atri A, Ballard C, Boneva N, Frolich L, Molinuevo JL, Raket LL, Tariot PN. Insights into globalization: comparison of patient characteristics and disease progression among geographic regions in a multinational Alzheimer’s disease clinical program. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-018-0443-2.

O’Brien J, Taylor JP, Ballard C, Barker RA, Bradley C, Burns A, Collerton D, Dave S, Dudley R, Francis P, Gibbons A, Harris K, Lawrence V, Leroi I, McKeith I, Michaelides M, Naik C, O’Callaghan C, Olsen K, Onofrj M, Pinto R, Russell G, Swann P, Thomas A, Urwyler P, Weil RS, Ffytche D. Visual hallucinations in neurological and ophthalmological disease: pathophysiology and management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(5):512–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2019-322702.

Watts KE, Storr NJ, Barr PG, Rajkumar AP. Systematic review of pharmacological interventions for people with Lewy body dementia. Aging Mental Health. 2022;1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2022.2032601.

Emre M, Tsolaki M, Bonuccelli U, Destee A, Tolosa E, Kutzelnigg A, Ceballos-Baumann A, Zdravkovic S, Bladstrom A, Jones R, Study I. Memantine for patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(10):969–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70194-0.

Lee C, Shen YC. Aripiprazole improves psychotic, cognitive, and motor symptoms in a patient with Lewy body dementia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;37(5):628–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000000769.

Sugawara Kikuchi Y, Shimizu T. Aripiprazole for the treatment of psychotic symptoms in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies: a case series. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:543–7. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S189050.

• Russo M, Carrarini C, Dono F, Rispoli MG, Di Pietro M, Di Stefano V, Ferri L, Bonanni L, Sensi SL, Onofrj M. The pharmacology of visual hallucinations in synucleinopathies. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1379. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.01379. This reference is an excellent source for understanding visual hallucinations in DLB, and how to manage them.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Mario F. Mendez declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Dementia

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mendez, M.F. Managing the Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia. Curr Treat Options Neurol 24, 183–201 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-022-00715-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-022-00715-6