Abstract

Behavioral and psychological symptoms are common in dementia, challenging to manage, and a leading cause of nursing home placement, decreased quality of life, and caregiver distress. This chapter provides a seven-step model for tailoring treatment of five common behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD): agitation/irritability/aggression, depression and anxiety, apathy, sleep disturbance, and wandering. A review of nonpharmacological and pharmacological interventions and practical strategies for addressing BPSD in the context of neuropsychology practice are included.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) is among the most difficult aspects of dementia care and a frequent focus in neuropsychological evaluations. Given that the rate of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is projected to increase exponentially to 7.1 million by 2025, and nearly triple to 13.4 million by 2050 [1], determining effective strategies for the management of BPSD is imperative.

Ineffective management of BPSD has significant negative emotional and functional consequences for the person with dementia (PWD) and his or her caregivers, and is the leading cause of nursing home placement [2]. BPSD often present with a sense of urgency due to distress experienced by the PWD and/or his or her caregivers, and sometimes due to related safety concerns. BPSD are frequently challenging to manage because they often require (a) customization of treatment recommendations, based on a detailed understanding of the problem behavior(s); (b) an iterative, context-dependent approach in determining effective treatment; (c) implementation of some interventions by caregivers; and (d) ongoing follow-up to adjust treatment as behaviors change in the context of increasing cognitive impairment.

This chapter provides a seven-step model for tailoring treatment of BPSD, based on empirically supported strategies from systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and clinical considerations. Pharmacological management strategies are summarized when applicable. Given that AD and AD-related mixed dementias account for 60–80% of all cases of dementia [1], BPSD in AD is a major focus of this chapter. Information on BPSD in other subtypes of dementia is also summarized when applicable.

BPSD Are Common and Persistent

Approximately 60–90% of patients with AD develop behavioral and psychological symptoms including hallucinations, delusions, agitation, dysphoria/depression, anxiety, irritability, disinhibition, apathy, sleep disturbances, and eating changes (3). Multiple studies have shown variable relative frequencies of different types of BPSD. Although mixed research findings make it difficult to determine the most common BPSD, there is great overlap in subtypes of BPSD across studies (see Table 23.1). For example, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 48 studies over 50 years showed that the most common BPSD in AD were apathy (49%), depression (42%), aggression (40%), anxiety (39%), sleep disorder (39%), irritability (36%), appetite disorder (34%), aberrant motor behavior (32%), delusions (31%), disinhibition (17%), and hallucinations (16%) [4]. Another systemic review of 23 studies demonstrated that the most common BPSD are delusions, wandering, agitation, aberrant motor behavior, and apathy [5], while other research showed that apathy, sleep problems, depression, irritability, and wandering were most common [6].

A study examining the relationship between BPSD and mortality over 10 years showed that most BPSD were persistent [6]. However, some BPSD may increase over time, while others may remain relatively stable. For example, a 3-year longitudinal study showed that delusions, hallucinations, agitation, anxiety, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, and aberrant motor behavior increased over time, whereas depression, euphoria, nighttime behavior, and appetite did not [7].

Predictors of BPSD in Different Subtypes of Dementia

Risk factors for increased BPSD in mild AD include younger age, male sex, and greater functional impairment. Increased severity of dementia and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) have also been associated with more BPSD at baseline [7]. Lewy body dementia has been associated with more hallucinations and fewer appetite disturbances as compared to FTD or AD, and AD has been associated with lower levels of BPSD than other dementias at baseline [7]. In AD, lower education has been shown to be associated with greater distress/tension, and Caucasians exhibited a higher prevalence of affective disorders than other groups [8].

The overall prevalence of BPSD in AD and vascular dementia (VaD) was comparable, and the relationship between higher rates of BPSD and impairment in activities of daily living in AD and VaD was similar, though the types of BPSD differed between groups. For example, patients with AD exhibited more agitation/aggression and irritability/lability than patients with VaD, and AD caregivers reported significantly higher levels of distress. Both groups showed significant associations between impairments in daily functioning and depression, apathy, irritability, and disordered sleep and eating [9].

Tailoring Treatment for BPSD: A Seven–Step Model

A multi-step approach to tailoring BPSD treatment (see Table 23.2), designed for integration into neuropsychology practice, helps ensure consideration of variables that have been shown to impact BPSD treatment success.

Step 1: Determine Subtype and Severity of Dementia

As previously noted, given that different subtypes of dementia are associated with different relative frequencies of BPSD, and given that BPSD incidence increases with dementia severity, determining the subtype and severity of dementia will help guide the focus on BPSD in the context of the neuropsychological evaluation.

Step 2: Specify BPSD Symptoms and Potential Contributing Variables

Several studies have shown that the success of nonpharmacological interventions in minimizing BPSD is dependent on tailoring the intervention to patient characteristics [10,11,12]. However, this is often challenging because BPSD may have multifactorial causes that directly impact the expression of symptoms, including neurobiological disease-related factors, unmet needs, caregiver variables, and environmental triggers [13].

As detailed elsewhere [14], a useful framework for specifying BSPD and clarifying potential contributing variables involves two primary steps:

-

(a)

Topographical assessment of BPSD, including

-

(a)

Identification of target behavior(s) (see Table 23.1)

-

(b)

Describing the intensity and frequency of target behaviors

-

(a)

-

(b)

Functional assessment of BPSD, including

-

(a)

Identification of factors that contribute to the etiology of BPSD through examination of the context in which BPSD occurs, with a focus on:

-

(i)

Factors that precede BPSD (“Antecedents”) (e.g. specific situations such as bathing, the presence of others, etc.)

-

(ii)

Factors that occur after the BPSD (“Consequences”), including adding favorable stimuli (positive reinforcement) or removing aversive stimuli such as task demands (negative reinforcement)

-

(iii)

“Setting events” that impact antecedents and consequences through contextual factors (e.g. pain, time of day, emotional state, etc.)

-

(i)

-

(a)

Data on these issues can be gathered in the context of the neurobehavioral interview. If there is a desire to obtain more detailed information, several inventories are available to measure these constructs [14].

Step 3: Assess and Strengthen Caregiver Engagement

Caregivers are fundamental partners in supporting effective behavior management and treatment compliance for the PWD. As dementia progresses, the PWD often becomes increasingly dependent on caregiver assistance with daily tasks and oversight of safety. This dependence often shifts the nature of the relationship between the caregiver and the PWD, and may contribute to caregiver stress.

During the neuropsychological assessment, it is often helpful to interview the primary caregiver in person (or via telephone if necessary) to determine the caregiver’s insight into the potential need for assistance, their level of engagement in caregiving activities, readiness to implement recommended treatment strategies, and need for support. Caregiver support can be helpful at many time points, but is ideally provided proactively to minimize chronic caregiving stress.

The Alzheimer’s Association provides a 24-h Helpline, support groups, and educational information that many caregivers find invaluable on the caregiving journey [15]. Many states also have local Aging and Disability Resource Centers that connect caregivers and PWD with local agencies to assist with management of medications, finances, housework, travel, meals, day programming, and respite services. Connecting caregivers to these and other support services early in the diagnostic process may help enhance caregiver readiness to implement treatment strategies. This may benefit the caregiver and the PWD, given that increased caregiver readiness is associated with a decrease in distressing behavioral symptoms in the PWD and greater caregiver confidence [16].

Beyond connecting caregivers to supportive resources, specific caregiver interventions have been identified as helpful in supporting community-dwelling PWD, including (a) providing opportunities for engagement of both the PWD and the caregiver; (b) encouraging caregiver participation in educational interventions; (c) offering individualized programs rather than group sessions; (d) providing information in an ongoing fashion; and (e) focusing on reducing specific concerning behaviors [17]. Individual behavioral interventions and multicomponent interventions are also helpful in improving the psychological health of caregivers, with the latter intervention also decreasing the rate of institutionalization for the PWD [18].

Step 4: Consider Increasing Daily Engagement for the PWD

Regardless of whether BPSD exist, regular exercise under the direction of a healthcare provider, a routine schedule, and increased engagement in personally enjoyable activities may help improve quality of life for the PWD and, by extension, the caregiver. Recommendations for increasing daily engagement are helpful to make early, at the point of dementia diagnosis (or even when a suspected progressive mild cognitive impairment is diagnosed), to potentially minimize the likelihood and/or severity of current or future BPSD.

Several factors have been shown to increase engagement for PWD. For example, stimuli that are personalized to the interests of the PWD [19, 20] or presented through one-on-one socialization [10] have been shown to be maximally engaging. Engagement in the visual arts has also been shown to be therapeutic for PWD [21], making museum and art programs for PWD and caregivers an increasingly popular activity [22]. In the nursing home setting, dog-related stimuli – including live dogs, puppy videos, and a dog-coloring activity – were associated with increased engagement [20]. In addition, live stimuli (including people) and social (vs. nonsocial) stimuli have been related to increased engagement [23]. However, the impact of simulated presence therapy [24] and massage/touch in promoting engagement in PWD has been inconclusive [25].

Aerobic exercise is another form of engagement that may assist in decreasing current and future BPSD. In individuals with AD, aerobic exercise has been shown to improve quality of life, psychological well-being, and systemic inflammation [26]. In early AD, aerobic exercise is associated with modest gains in functional ability, cardiorespiratory fitness, and reduced hippocampal atrophy [27], all of which – in addition to the increased fatigue and positive distraction that accompanies aerobic exercise – may help decrease BPSD intensity. Attempting to proactively offset the impact of variables that decrease exercise engagement may also help minimize future BPSD severity. Variables associated with decreased exercise engagement include female sex, older age, and increased medication use, while those associated with increased exercise include higher functional and cognitive status [28].

New directions for increasing engagement in persons with early-stage dementia include the use of positive psychological measures, including constructs of gratitude, life satisfaction, meaning in life, optimism, and resilience, with the goal of developing strength-based psychosocial interventions [29].

Step 5: Add Customized Management Strategies Based on BPSD Symptoms, with a Focus on Behavior Therapy

Individualized behavior therapy has been shown to be helpful in reducing all BPSD summarized below and as such is recommended as a first-line nonpharmacological treatment consideration for agitation/irritability/aggression, depression and anxiety, apathy, sleep disturbance, and wandering. Music therapy also has robust effects in reducing agitation/irritability/aggression, as well as depression and anxiety. Details on these findings and other specialized interventions are summarized below.

Agitation, Irritability, and Aggression

Agitation occurs especially in the middle and late stages of AD [30]. Common behavioral expressions of agitation include excessive psychomotor activity, aggressive behaviors, irritability, and repetitive behaviors. Three psychosocial models have been postulated to explain possible contributors to agitated or aggressive behavior, and suggest that behavior may represent (a) an expression of “unmet needs”; (b) a response to environmental stimuli; and/or (c) a reduced threshold for stress [31]. Examining these potential factors can help refine treatment recommendations.

Nonpharmacological Interventions

Nonpharmacological interventions are recommended as a first-line treatment, unless BPSD symptoms are severe, persistent, or recurrent [5]. Adding pharmacological agents may lead to side effects and increase overall medication burden. In cases of moderate to severe agitation, a combination of pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions should be considered. Tailoring interventions by examining agitated behaviors from the standpoint of how the PWD may be expressing “unmet needs” has been shown to help decrease aggression [32]. Some research has shown that agitation is the most responsive BPSD to nonpharmacological interventions, as compared to other BPSD including depression, apathy, repetitive questioning, psychosis, aggression, sleep problems, and wandering [33].

Across multiple studies, music has been shown to be a powerful tool in reducing aggressive behaviors. For example, a recent meta-analysis of 12 studies demonstrated that music had clinically and statistically robust effects on agitation (as defined by repetitive acts, restlessness, wandering, and aggressive behaviors; [34]). Similar findings were noted in a recent review of eight randomized controlled trials that showed individualized and interactive music therapy was optimal for management of agitation in institutionalized patients with moderate to severe AD [30]. A recent systemic review of 34 studies provided similar support for individualized music [35].

Music therapy and behavioral techniques were shown to be superior in reducing aggression, agitation, and anxiety, as compared to other therapies including sensory stimulation, cognitive/emotion-oriented interventions (e.g., music/dance therapy, reminiscence therapy, and simulated presence therapy), exercise, and animal-assisted therapy [36]. Another study demonstrated similar positive effects of behavioral therapies in reducing aggression [37]. The relationship between aromatherapy and agitation has also been studied, though findings have been mixed. One study found no significant benefit of aromatherapy in managing agitation [30], though another study showed aromatherapy helped to reduce agitation but not other behaviors such as restlessness/wandering, anger, and anxiety [38].

Engaging with animals, dolls, and robotic animals has also been found to reduce agitation. In a review of 12 studies, doll therapy – a person-centered therapy involving holding, talking to, feeding, cuddling, or dressing an anthropomorphic doll – was found to effectively reduce agitation and aggression [39]. Engagement with animals [40] and a robotic cat was also shown to decrease agitation [41].

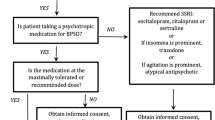

Pharmacological and Other Medical Interventions

Although antipsychotic medication is sometimes used to manage agitation in dementia, it has been linked to increased mortality [42], and the use of antipsychotics has declined in light of the black box warning from the Food and Drug Administration [43]. However, the need for effective treatment of agitation has contributed to the study of several other pharmacological agents.

Cholinesterase inhibitors have been shown to be effective in reducing and delaying agitation [3, 44] as well as reducing the need for other medications to manage agitation [3]. Dosage of cholinesterase inhibitors may be an important factor in managing BPSD, based on findings that increasing the dosage of donepezil (from 5 to 10 mg day) improved behavioral symptoms in individuals with Lewy body dementia [45]. Memantine for BPSD in AD has also been shown to reduce the dose of other medications that are used in managing agitation, including diazepam [46].

Multiple studies have indicated the benefit of citalopram in treating agitation in AD [47, 48], though side effects have also been noted. For example, one study showed that citalopram decreased delusions, anxiety, and irritability after 9 weeks, but increased the severity of sleep behavior disorders after week 9 [49]. Another study found that 30 mg daily of citalopram helped to significantly decrease agitation in AD. However, cognitive worsening was also noted, and it was thus recommended that citalopram 20 mg daily be considered as a first-line treatment in addition to psychosocial interventions [50]. A review of clinical trials evaluating pharmacologic interventions for agitation in AD noted that a range of medications hold promise in treating agitation, including dextromethorphan/quinidine, scyllo-inositol, brexpiprazole, prazosin, cannabinoids, citalopram, escitalopram, and pimavanserin [51].

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is another potential treatment for agitation, based on a study demonstrating that 72% of individuals with acute aggression, agitation, and disorganized behavior secondary to dementia showed a clinically meaningful response to ECT. Maintenance treatment was effective in sustaining the treatment response in 87% of cases, though two cases of significant cognitive adverse effects were noted [52].

Depression and Anxiety

Increased involvement in positive events and enhanced caregiver problem solving have been shown to decrease depression in PWD [53]. Music has also been found to be helpful in treating depression [35, 54, 55] and anxiety [35, 54]. However, the therapeutic benefit of music may depend on dementia severity. For example, in elderly patients with severe dementia, multisensory stimulation environments were shown to reduce anxiety and agitation more than individualized music sessions [56]. Reminiscence interventions were also linked to improved mood, decreased caregiver burden, decreased dysfunctional behaviors, and reduced institutionalization in AD [37].

In regard to pharmacological management, Citalopram has been shown to be helpful in treating anxiety [49]. However, a 2017 analysis of double-blind randomized controlled trials comparing antidepressants versus placebo for depression in AD found no statistically significant difference between antidepressants (including sertraline, mirtazapine, imipramine, fluoxetine, and clomipramine) and placebo, and concluded that higher-quality randomized controlled trials are needed [57].

Apathy

Apathy is associated with poorer disease outcome, reduced daily functioning, and increased caregiver distress [58]. Apathy is also the most stable and persistent BPSD over 10-year follow-up, and is associated with a threefold increase in mortality compared to other BPSD [6]. Given that disruption of frontal-subcortical networks is likely linked to apathy in AD [59], assessing for the presence of apathy in individuals with frontal subcortical neurocognitive deficits can be informative. Nonpharmacological interventions such as individualized therapeutic activities [60] have demonstrated promise in treating apathy. In addition, short-term occupational therapy was shown to be more effective in reducing apathy than engaging in an activity of choice [61]. Pharmacological agents including acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, gingko biloba, and methylphenidate have been found to help reduce apathy in patients with AD [58].

Sleep Disturbance

Light therapy, increased physical and social activity, and multicomponent cognitive behavioral interventions have been shown to help treat sleep disturbance in dementia [62]. Unfortunately, a recent review on pharmacological management for sleep disturbances in dementia found a lack of evidence to guide drug treatment, including no randomized controlled trials of the many drugs that are widely prescribed for sleep problems and dementia, such as benzodiazepine and non-benzodiazepine hypnotics. There was no evidence that melatonin (up to 10 mg) helped sleep problems in individuals with moderate to severe AD. There was some evidence that low-dose trazodone (50 mg) was helpful, though a larger trial was recommended. There was no evidence of any effect of ramelteon on sleep problems in moderate to severe AD [63].

Wandering

The risk of wandering and getting lost increases as dementia and cognitive impairment worsen. Wandering also frequently creates anxiety, distress, and decreased interactions in PWD [64]. Proactively connecting caregivers to the Alzheimer’s Association to learn about the Safe Return registration program [15] can provides support and education about wandering, and more rapid identification of the PWD if wandering occurs. Analyzing patterns related to wandering (e.g., time of day, presence/absence of others, boredom, hunger) can assist in assessing potential “unmet needs” and other variables related to wandering, and provide tailored solutions. Environmental modifications are also often helpful, including disguising locks on doors or doorknobs and using door alarms. Some studies have examined the potential of using global positioning system (GPS) devices to promote safe walking and provide early alerts about potential wandering, though legal issues related to privacy and autonomy are noted [65].

Wandering often increases in residential environments where hallways and/or rooms are undifferentiated. The use of visual cues to assist in wayfinding is beneficial, including the use of colorful, easily identifiable, personally meaningful cues at key environmental decision points such as resident rooms [64]. Other strategies in long-term care settings include environmental modifications (e.g., a secure place to wander, a wall mural, and other visual strategies to disguise exits), music, exercise, structured activities to decrease wandering, and caregiver education [66]. Environmental modifications are discussed in greater detail in other chapters.

Step 6: Consider Medical Consultation

Medical consultation is often helpful in creating the most effective BPSD treatment plan and helps determine whether BPSD are related to metabolic or other medical issues, and whether adjunctive pharmacological therapy or other medical treatments are warranted. Ongoing communication with medical colleagues about the efficacy of treatment interventions helps ensure that treatments are complimentary and coordinated.

Step 7: Recommend Treatment Tracking and Follow-Up

As previously discussed, caregiver engagement is crucial to treatment success. It is often helpful to recommend that caregivers keep a journal regarding the effectiveness of recommended interventions and are encouraged to share that information with healthcare providers. Caregivers also benefit from having a point of contact for questions that arise between appointments. Caregivers often report feeling more engaged and empowered when they perceive they are part of a team of healthcare professionals and community experts that are dedicated to providing care for their loved one.

Clinical Pearls

-

At the point of initial diagnosis of dementia or when a suspected progressive mild cognitive impairment is diagnosed, consider recommending strategies to increase engagement and quality of life for the PWD – including exercise, maintaining a schedule, and engagement in personally enjoyable activities – in order to minimize the likelihood of current and future BPSD.

-

Medical issues should always be ruled out as a contributing factor to BPSD, even if BPSD are chronic.

-

An iterative approach to behavioral management is often required before behavior consistently improves, and often necessitates that the caregiver have an ongoing point of contact for treatment input.

-

Neuropsychologists are uniquely trained to customize BPSD treatment plans by integrating information from cognitive, psychiatric, and behavioral variables, and would benefit from highlighting this skill to referral sources if this is a desired area of practice.

-

When in doubt about what to recommend for BPSD treatment, consider suggesting a behavioral intervention, given that behavioral interventions have the strongest and widest range of support across different subtypes of BPSD.

References

2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. https://www.alz.org/documents_custom/2016-facts-and-figures.pdf. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

Managing behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. http://www.alz.org/documents_custom/hcp_MD_BPSD.pdf. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

Cummings J, Lai TJ, Hemrungrojn S, Mohandas E, Yun Kim S, Nair G, et al. Role of donepezil in the Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016;22:159–66.

Zhao QF, Tan L, Wang HF, Jiang T, Tan MS, Tan L, et al. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:264–71.

Borsje P, Wetzels RB, Lucassen PL, Pot AM, Koopmans RT. The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in community-dwelling patients with dementia: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27:385–405.

van der Linde RM, Matthews FE, Dening T, Brayne C. Patterns and persistence of behavioural and psychological symptoms in those with cognitive impairment: the importance of apathy. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32:306–15.

Brodaty H, Connors MH, Xu J, Woodward M, Ames D. The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: a 3-year longitudinal study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:380–7.

Apostolova LG, Di LJ, Duffy EL, Brook J, Elashoff D, et al. Risk factors for behavioral abnormalities in mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;37:315–26.

D’Onofrio G, Sancarlo D, Panza F, Copetti M, Cascavilla L, Paris F, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional status in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia patients. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:759–71.

Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx M, Dakeel-Ali M, Regier MG, Thein K. Can persons with dementia be engaged with stimuli? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:351–62.

Guarlnik JM, Levielle S, Volpato S, Marx M, Cohen-Mansfield J. Targeting high-risk older adults into exercise programs for disability prevention. J Aging Phys Act. 2003;11:219–28.

Cohen-Mansfield J. Use of patient characteristics to determine nonpharmacologic interventions for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int psycho geriatr. 2000;12:373–80.

Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ. 2015;350:h369.

Fisher JE, Harsin CW, Hayden JE. Behavioral interventions for patients with dementia. In: Molinari V, editor. Professional Psychology in long-term care. New York: Hatherleigh; 2000. p. 179–200.

Alzheimer’s Association 24/7 Helpline webpage. http://www.alz.org/we_can_help_24_7_helpline.asp. Accessed July 1, 2017.

Gitlin LN, Rose K. Impact of caregiver readiness on outcomes of a nonpharmacological intervention to address behavioral symptoms in persons with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31:1056–63.

Parker D, Mills S, Abbey J. Effectiveness of interventions that assist caregivers to support people with dementia living in the community: a systematic review. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2008;6:137–72.

Health Quality Ontario. Caregiver- and patient-directed interventions for dementia: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2008;8:1–98.

Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx M, Thein K, Dakeel-Ali M. The impact past and present preferences on stimulus engagement in nursing home residents with dementia. Age & Mental Health. 2010;14:67–73.

Cohen-Mansfield J, Thein K, Dakeel-Ali M, Marx M. The underlying meaning of stimuli: impact on engagement of persons with dementia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177:216–22.

Chancellor B, Duncan A, Chatterjee A. Art therapy for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. J Alz Dis. 2014;39:1–11.

Camic PM, Tischler V, Pearman CH. Viewing and making art together: A multi-session art-gallery based intervention for people with dementia and their carers. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18:161–8.

Cohen-Mansfield J, Thein K, Dakeel-Ali M, Regier MG, Marx M. The value of social attributes of stimuli in promoting engagement in persons with dementia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:586–92.

Abraha I, Rimland JM, Lozano-Montoya I, Dell’Aquila G, Vélez-Díaz-Pallarés M, Trotta FM, et al. Simeulated presence therapy for dementia. Cochrane database Syst rev. 2017;18:4.

Wu J, Wang Y, & Wang Z. The effectiveness of massage and touch on behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: a quantitative systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs 2017;5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13311. [Epub ahead of print].

Abd El-Kader SM, Al-Jiffri OH. Aerobic exercise improves quality of life, psychological Well-being and systemic inflammation in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease. Afr Health Sci. 2016;16:1045–55.

Morris JK, Vidoni ED, Johnson DK, Van Sciver A, Mahnken JD, Honea RA, et al. Aerobic exercise for Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized controlled pilot trial. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170547.

Cohen-Mansfield J, Lipson S. Pain in cognitively impaired nursing home residence: how well are physicians diagnosing it? J Am Ger Soc. 2002;50:1039–44.

McGee JS, Zhao HC, Myers DR, Kim SM. Positive psychological assessment and early-stage dementia. Clin Gerontol. 2017;9:1–13.

Millán-Calenti JC, Lorenzo-López L, Alonso-Búa B, de Labra C, González-Abraldes I, Maseda A. Optimal nonpharmacological management of agitation in Alzheimer’s disease: challenges and solutions. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:175–84.

Cohen-Mansfield J. Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors and dementia: a review, summary, and critique. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9:361–81.

Cohen-Mansfield J, Liben A, Marx M. Nonpharmacologic treatment of agitation: A controlled trial of systematic individualized intervention. J Gerontol: Series A. 2007;62:908–16.

de Oliveira, Radanovic M, Homem de Mello PC, Buchain PC, Vizzotto ADB, Celestino DL et al. Nonpharmacological interventions to reduce behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a systematic review. BioMed Res Intl. 2015;Art ID 218980.

Pedersen SKA, Andersen PN, Lugo RG, Andreassen M, Sütterlin S. Effects of music on agitation in dementia: a meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2017;8:742.

Travers C, Brooks D, Hines S, O’Reilly M, McMaster M, He W, et al. Effectiveness of meaningful occupation interventions for people living with dementia in residential aged care: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14:163–225.

Abraha I, Rimland JM, Trotta FM, Dell’Aquila G, Cruz-Jentoft A, Petrovic M, et al. Systematic review of systematic reviews of non-pharmacological interventions to treat behavioural disturbances in older patients with dementia. The SENATOR-OnTop series. BMJ Open. 2017;16:e012759.

Dourado MC, Laks J. Psychological interventions for neuropsychiatric disturbances in mild and moderate Alzheimer’s disease: current evidences and future directions. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2016;13:1100–11.

Moorman Li R, Gilbert B, Orman A, Aldridge P, Leger-Krall S, Anderson C, et al. Evaluating the effects of diffused lavender in an adult day care center for patients with dementia in an effort to decrease behavioral issues: a pilot study. J Drug Assess. 2017;6:1–5.

Ng QX, Ho CY, Koh SS, Tan WC, Chan HW. Doll therapy for dementia sufferers: a systematic review. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2017;26:42–6.

Richeson NE. Effects of animal-assisted therapy on agitated behaviors and social interactions of older adults with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dem. 2003;18:353–8.

Liben A, Cohen-Mansfield J. Therapeutic robocat for nursing home residents with dementia: preliminary inquiry. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dem. 2004;19:111–6.

Steinberg M, Lyketsos CG. Atypical antipsychotic use in patients with dementia: managing safety concerns. Am J Psychiatr. 2012;169:900–6.

Dorsey RE, Rabbani A, Gallagher SA, Conti RM, Alexander GC. Impact of FDA black-box advisory on antipsychotic medication use. Arch Int Med. 2010;170:96–103.

Gabryelewicz T. Pharmacological treatment of behavioral symptoms in dementia patients. Przegl Lek. 2014;71(4):215–20.

Manabe Y, Ino T, Yamanaka K, Kosaka K. Increased dosage of donepezil for the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in dementia with Lewy bodies. Psychogeriatrics. 2016;16:202–8.

Suzuki H, Inoue Y, Nishiyama A, Mikami K, Gen K. Clinical efficacy and changes in the dosages of concomitantly used psychotropic drugs in memantine therapy in Alzheimer’s disease with behavioral and psychological symptoms on dementia. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2013;3:123–8.

Ballard CG, Gauthier S, Cummings JL, Brodaty H, Grossberg GT, Robert P, et al. Management of agitation and aggression associated with Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:245–55.

Siddique H, Hynan LS, Weiner MF. Effect of a serotonin reuptake inhibitor on irritability, apathy, and psychotic symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:915–8.

Leonpacher AK, Peters ME, Drye LT, Makino KM, Newell JA, Devanand DP. Effects of Citalopram on Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Dementia: Evidence from the CitAD study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:473–80.

Porsteinsson AP, Keltz MA, Smith JS. Role of citalopram in the treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2014;4:345–9.

Porsteinsson AP, Antonsdottir IM. An update on the advancements in the treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18:611–20.

Isserles M, Daskalakis ZJ, Kumar S, Rajji TK, Blumberger DM. Clinical effectiveness and tolerability of electroconvulsive therapy in patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57:45–51.

Teri L, Logsdon RG, Uomoto J, McCurry SM. Behavioral treatment of depression in dementia patients: a controlled clinical trial. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997;52B:P159–66.

Gómez GM, Gómez GJ. Music therapy and Alzheimer’s disease: cognitive, psychological, and behavioural effects. Neurologia. 2017;32:300–8.

Ray KD, Mittelman MS. Music therapy: a nonpharmacological approach to the care of agitation and depressive symptoms for nursing home residents with dementia. Dementia (London). 2015. pii: 1471301215613779. [Epub ahead of print].

Sánchez A, Maseda A, Marante-Moar MP, de Labra C, Lorenzo-López L, Millán-Calenti JC. Comparing the effects of multisensory stimulation and individualized music sessions on elderly people with severe dementia: a randomized controlled trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52:303–15.

Orgeta V, Tabet N, Nilforooshan R, Howard R. Efficacy of antidepressants for depression in alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58:725–33.

Theleritis C, Siarkos K, Katirtzoglou E, Politis A. Pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment for apathy in Alzheimer disease: a systematic review across modalities. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2017;30:26–49.

Theleritis PA, Siarkos K, Lyketsos CG. A review of neuroimaging findings of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:195–207.

Brodaty HM, Burns KB. Nonpharmacological management of apathy in dementia: a systematic review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;20:549–64.

Ferrero-Arias J, Goñi-Imízcoz M, González-Bernal J, Lara-Ortega F, da Silva-González Á, Díez-Lopez M. The efficacy of non-pharmacological treatment for dementia related apathy. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Dis. 2011;25:213–9.

Deschenes CL, McCurry SM. Current treatments for sleep disturbances in individuals with dementia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11:20–6.

McCleery J, Cohen DA, Sharpley AL. Pharmacotherapies for sleep disturbances in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD009178.

Davis R, Weisbeck C. Creating a supportive environment using cues for wayfinding in dementia. J Gerontol Nurs. 2016;42:36–44.

Topfer LA. GPS locator devices for people with dementia. In: CADTH Issues in Emerging Health Technologies. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in health: Ottawa (ON); 2016. p. 147.

Futrell MF, Devereaux Melillo K, Remington R. Evidence-based practice guideline: wandering. J Geron Nurs. 2014;40:16–23.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Braun, M. (2019). Management of Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms in Dementia. In: Ravdin, L.D., Katzen, H.L. (eds) Handbook on the Neuropsychology of Aging and Dementia. Clinical Handbooks in Neuropsychology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93497-6_23

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93497-6_23

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-93496-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-93497-6

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)