Abstract

Purpose of Review

We examined the various ways that religiousness influences sexual health, elucidating the mechanisms responsible for both helpful and harmful effects.

Recent Findings

Religious beliefs, behavior, and belonging influence sexual health by (a) discouraging specific sexual behaviors, (b) discouraging sex generally, (c) encouraging sex only in a heterosexual marriage, (d) encouraging sex only for procreation, (e) framing sex as a sacred spiritual act, (f) providing a community of support, and (g) reinforcing sexual norms. These beliefs, behaviors, and sense of belonging may undermine or support sexual health knowledge, sexual functioning, sexual satisfaction, perceptions of compulsive sexual behavior, recovery from sexual violence, sexually conservative behavior, sex anxiety, and sex guilt/shame.

Summary

Religious beliefs, behaviors, and sense of belonging simultaneously undermine and support sexual health. “Both/and” approaches that hold this dialectic undermining and support are more helpful in guiding future work rather than “either/or” approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sexuality is a central aspect of human experience that includes “sexual thoughts, fantasies, beliefs, behaviors, and relationships” [1••]. For many, religiousness—or the search for the sacred in the context of culturally sanctioned institutions [2]—is also a central aspect of human experience that may impact individuals’ experiences of both sexuality and sexual health (i.e., a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being related to sexuality) [1••]. Religiousness’ influence on sexual health depends on many factors, including the content and strength of individuals’ religious beliefs, the degree to which individuals feel like they belong with coreligionists and the social expectations of that group, and the specific religious behaviors a religious tradition encourages/discourages [3•, 4•].

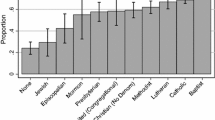

We describe the ways that religious behaving, believing, and belonging influence sexual health in Fig. 1. Although we differentiate the influence of behaving, believing, and belonging on a variety of sexual health outcomes, each of these dimensions of religiousness is related to the others, and as such, there is substantial overlap between dimensions of religiousness in their influence on sexual health outcomes. We largely focus our review on the experiences of cisgender/heterosexual individuals or “people generally,” though we note that robust models have been developed for how religiousness influences the health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning individuals [5••, 6].

Religious Beliefs

Religious beliefs—the ways that people internalize religious teachings and their internal representations of the sacred [3•]—may influence sexual health both directly and indirectly. Religious beliefs may directly impact sexual health because of their capacity to influence a person’s internal cognitive and emotional experience during sex. Religious beliefs may also indirectly impact sexual health via their influence on sexual behaviors and association with other external factors. The nature of the impact of religious beliefs on sexual health depends on a variety of factors including the content of the beliefs, the degree to which someone holds a belief, the sexual health outcome in question, gender, sexual orientation, and marital status.

Sexual Functioning

Many religious teachings frame sex as a sacred spiritual act appropriate only in the context of heterosexual marriage. Though there is substantial variation between traditions, most Christian religious traditions have historically discouraged sex for the sole purpose of experiencing pleasure and consequently regard sexual behaviors like oral sex, anal sex, and masturbation as unnatural and immoral as they have no procreative value [7,8,9]. Thus, many religious individuals believe in abstaining from non-procreative sexual behaviors and/or sex outside of heterosexual marriage and may attempt to deny or suppress sexual urges that they believe to be sinful [10]. These beliefs can impact sexual functioning (i.e., levels of sexual desire and arousal, problematic orgasmic functioning, and pain associated with sexual activity) by fostering psychological conflict when behaviors and beliefs do not align, promoting sex guilt and sex anxiety, and leading to inaccurate and problematic cognitions about sex [11,12,13,14].

While there is some evidence that suggests religious beliefs can negatively impact sexual function in men (e.g., erectile dysfunction) [15], religiously rooted sexual dysfunction appears to be far more prevalent in women. Among women, religious beliefs about sex can contribute to problems with sexual function like difficulty achieving orgasm [16, 17], dyspareunia (i.e., painful vaginal intercourse) [11, 18, 19], vaginismus (i.e., involuntary spasms of the muscles surrounding the vagina during intercourse that prevent penetration) [20,21,22], and sexual desire dysfunction [14, 23, 24]. Women may experience greater risk for problems with sexual function related to their religious beliefs than men due to the degree to which women’s value is associated with their sexual purity in religious contexts, religious restrictions on women’s pleasure, and teachings that frame women as being primarily responsible for eliciting and preventing sexual temptation [25, 26]. Even when sex is religiously sanctioned (e.g., in a heterosexual marriage), women’s sexual functioning may still be impaired because of the difficulty shifting away from pre-marital notions of sex as something dirty, immoral, and sinful [26]. Similarly, women raised with religious beliefs about abstinence and premarital sex may continue to experience associated sexual dysfunction, even if they no longer ascribing to these beliefs [19].

Compulsive Sexual Behavior

Religious beliefs may also influence sexual health due to their role in the development and/or perception of compulsive sexual behavior (CSB; i.e., repetitive and intense preoccupations with sexual fantasies, urges, and behaviors) [1••, 27]. Religious teachings about sex lead many religious individuals to develop a set of rigid beliefs about the moral nature of certain sexual thoughts, urges, and behaviors (e.g., viewing pornography, sexual thoughts about others while married) [28]. Religious individuals who believe that certain sexual thoughts/urges are immoral are both more likely to attempt to control them and to perceive these thoughts/urges as being out of control [29, 30]. Efforts to avoid or suppress “immoral” sexual thoughts/urges are typically counterproductive and can increase the frequency with which these thoughts/urges occur, their strength, and the likelihood of engaging in the behaviors the thoughts/urges lead to [28,29,30,31,32].

Men appear to be more likely than women to report CSBs [33, 34] with reporting pornography-related CSB being particularly common among religious men [33]. Despite these self-reports, many of the men who describe themselves as having CSB do not meet diagnostic criteria for pornography-related CSB and may instead be experiencing “perceived problematic pornography use” due to their religious beliefs and moral judgements about the acceptability of their sexual thoughts, urges, and behaviors [33, 35••, 36,37,38]. That is, religious individuals are more likely to perceive their pornography use (and other sexual urges and behaviors) as compulsive because they believe they are immoral, regardless of whether their sexual behaviors would objectively be considered dysregulated. Interestingly, approaches to treating CSB that are rooted in religious beliefs – such as 12-step programs – may complicate the experience of CSB by contributing to moral judgements of one’s sexual behaviors and increasing feelings of shame [39]. Despite the ways religious beliefs may complicate the experience and treatment of CSB, beliefs may also be seen as helping aid in recovery from CSB for some people [40, 41] and their spouses [42].

Sexual Health Knowledge and Sexual Education

Many religious traditions have specific beliefs about the contexts in which it is appropriate to discuss sex and often discourage conversations about sexual issues outside of a marriage unless seeking religious or medical guidance [43, 44]. Religious individuals tend to primarily receive sex education from religious sources [8], which frequently take an abstinence-only approach [45]. In turn, receiving education solely from an abstinence-only approach can lead religious individuals to develop inaccurate and/or extremely limited sexual health knowledge [25, 26, 45, 46], seek additional sexual education from unreliable or unrealistic sources [47], have difficulties with sexual communication [46] and experience feelings of shame when seeking supplemental information to fill in the gaps in their sexual knowledge [43]. Having limited sexual health knowledge—often due to abstinence-only sexual education promoted in religious traditions and communities—can contribute to other sexual health issues, such as emotional and functional issues upon become sexually active [43], improper or reduced use of contraception [48,49,50], and higher rates of teenage pregnancy and birth [51]. The implications of religious influences on sex education may be particularly concerning for gender and sexual minorities, as abstinence only sex education is more likely to contain disaffirming content [52] and less likely to include sexual and gender minority relevant sexual health topics [53].

Recovery from Sexual Violence

Religious beliefs may simultaneously promote and hinder recovery from sexual violence. Individuals who experience sexual violence often face trauma and an arduous journey of recovering a sense of safety and comfort with their own body [54, 55]. Religious beliefs about the role of women and attitudes towards sexual violence can reinforce cultural myths and misinformation surrounding sexual violence, contributing to the stigmatization that survivors of sexual violence face [56,57,58]. These religiously rooted beliefs may worsen post-traumatic mental health outcomes [59] and inhibit religious survivors from seeking religious support during their recovery process [60, 61]. Furthermore, as most religious traditions believe in a benevolent and all-powerful God, many survivors of sexual violence struggle to reconcile their views of a God who is good and capable of preventing violence with their feelings of powerlessness, personal blame, and anger from experiencing sexual violence [62]. Alternatively, many survivors benefit from their religious beliefs during the recovery process, potentially due to the ways that religious meaning making can facilitate acceptance [62], foster hope and resilience [58, 63, 64], and increase one’s feelings of control and perception of personal growth after experiencing sexual violence [65, 66]. For some, religious beliefs may facilitate a recovery process from sexual violence that begins with feelings of frustration, denial, and doubt but culminates with acceptance, calm, and comfort from finding spiritual meaning in one’s experience with sexual violence [62]. Religious communities (which we discuss in more detail later) may also help provide a sense of safety and connection with others during a time when those recovering from sexual violence feel isolated or fearful to be around others [57].

Sexual Satisfaction

Religious beliefs may also promote and undermine sexual satisfaction, at least in part due to the differential impact of religious beliefs on one’s sexual experiences. A large body of research suggests that religiousness is associated with greater sexual satisfaction among heterosexual married individuals by way of sexual sanctification (i.e., the belief that sex is sacred and has divine significance [67,68,69,70,71,72]. The belief that one’s sex life is ordained and maintained by God may increase sexual satisfaction by imbuing additional meaning and purpose, fostering a sense of increased connection to one’s spouse and to God [73], and potentially by buffering the effects of sexual guilt [68].

However, the positive effects of religious beliefs on sexual satisfaction vis-à-vis sanctification are likely limited to married heterosexual individuals due to religious beliefs surrounding premarital and non-heterosexual sex [68, 74]. Non-married and non-heterosexual religious individuals who are sexually active are, by nature of their marital status/sexual orientation, engaging in sexual behaviors that are likely incongruent with their religious beliefs. This may result in lower sexual satisfaction by preventing these individuals from viewing their sexual behaviors as divinely ordained and contributing to feelings of sexual guilt [68, 74, 75], reducing sexual frequency [76, 77], and inhibiting engagement in pleasurable but stigmatized sexual behaviors like oral sex, anal sex, and masturbation [10]. Religious beliefs may play a particularly significant role in inhibiting sexual satisfaction among women [71, 78], and sexual minorities [79] who may be more likely to view their sexual behaviors as incongruent with their moral beliefs which can inhibit sexual self-esteem and contribute to sexual guilt and shame [75, 79].

Religious Behavior

The discouragement of specific sexual behaviors through religious doctrine and community norms—such as premarital sex, extramarital sex, casual sex, and sex with multiple partners—influences the sexual health of religious individuals both in targeted and general ways. Most simply, discouraging certain sexual behaviors through religious influence leads to a reduction of those behaviors. More generally, because most religious traditions have extensive teachings about when and how not to have sex and few if any teachings about how to have sex, religious proscriptions can effectually reduce all sexual behaviors.

“Risky” Sexual Behavior/Sexually Conservative Behaviors

Much of the literature on religion and sexual behaviors utilizes language and framework of risky sexual behavior. “Risky” sexual behavior or sexual “risk” behavior often includes (a) sex with multiple partners, (b) sex with newer acquaintances, (c) sex with people who are having sex with other people, (d) hookup sex, (e) sex while consuming alcohol or other substances, (f) unprotected sex, (g) sex before age 15, (h) anal sex, (i) sex with someone who is more than five years older than you (as a teen), and (j) exchanging sex for money [80,81,82]. These behaviors are typically thought to be risky because they increase the change of either pregnancy or a sexually transmitted infection (STI). A closer examination of the specific behaviors classified as “risky” reveals, however, that while many behaviors included in this list are clearly related to pregnancy or STIs (e.g., unprotected sex; sex with multiple partners), many other behaviors either clearly have no connection to pregnancy or STI rate (e.g., anal sex, sex before 15) or are indirectly related (e.g., sex while consuming alcohol or other substances). In contrast, all of the behaviors listed could accurately be described as sexually conservative behaviors. The language of sexually conservative behaviors clearly recognizes the role of conservative moral values in the selection of sexual behaviors included in the category and does not unnecessary conflate notions of health with sexual behaviors. As such, we utilize the langue of sexually conservative behaviors rather than risky sexual behaviors to describe the range of sexual behaviors targeted by religious traditions and communities.

When risky sexual behaviors are framed as sexually conservative behaviors, the link between religiousness and a conservative sexual ethic is much more intuitive [83, 84]. Religious teachings about sexuality—which tend to be conservative in nature [85]—directly lead religious individuals to engage in fewer sexually explorative behaviors and more sexually conservative behaviors [86]. This relationship is well established, both in the recent and distant past. Indeed, religiousness has been shown to be related to (a) having fewer sexual partners [8, 50, 87,88,89], (b) engaging in less casual sex [83, 84], (c) a later age of sexual debut [87, 89], (d) being more likely to only date one person at a time [80, 84, 90], (e) not using substances while having sex [49, 80, 82, 90], (f) having less oral sex [10, 91], and (g) masturbating less often [10]. Further, these religious proscriptions may lead LGBTQ + people to pair in mixed-orientation relationships (i.e., one partner is heterosexual/cisgender and the other partner is LGBTQ +) [92, 93], to live lives of celibacy [94, 95], or to reject an LGBTQ + identity [96, 97].

Sexually Transmitted Infections and Sexual Aggression

A downstream impact of religious proscriptions about sex is that they can also lead people to have less sex generally, which may have other impacts. For example, religious people tend to have fewer sexually transmitted infections [49, 81, 90], due at least in part to the fact that religious people tend to engage in fewer sexual activities than nonreligious people [89].

Similarly, meta-analytic and other evidence suggests that religiousness is related to decreased sexual aggression [98,99,100], and one clear explanation for this finding is that religious people are less likely to be in situations where sexual aggression could be at play. Conversely, religiousness may promote false beliefs about rape [101] and sexual coercion in marriage by reinforcing stereotypic gender roles [102].

Religious Belonging

Religious belonging—including feelings of acceptance, security, and support from being a member of one’s religious tradition or community [3•, 4•]—influences sexual health by reinforcing religious beliefs and behaviors and by leading religious individuals to experience a variety of emotions in response to their sexuality and sexual experiences. Emotional responses to experiences such as sex are often shared as normative within religious communities [3•]. The violation of religious teachings surrounding “appropriate” sexual behavior may thus lead to community disapproval, which threatens belonging and can lead to feelings of anxiety, shame, and guilt, as well as less sexual satisfaction. Inversely, having a sense of belonging and support from religious communities can help those who face sexual violence to recover and reestablish a sense of safety and purpose.

Sex Anxiety

Individuals who feel a strong sense of belongingness to their religious community may experience heightened anxiety surrounding sexual health due to perceived expectations and morality of coreligionists, as well as a general lack of information. Religious communities often discuss sexual behaviors as immoral and against religious values, focusing less on factual information and more on doctrinal positions [12]. Consequently, those who are raised in such religious communities and environments demonstrate increased levels of anxiety around sexual behaviors [103, 104]. Such anxiety is evident beginning in adolescence [30] and is more potent for women [75], who often face stronger messages regarding the need for sexual abstinence. Anxiety surrounding sexual behaviors is also exacerbated for those who feel they belong to religious groups where coreligionists speak negatively regarding both sexual attractions and behaviors [105], resulting in intense fears among those who sexually engage with others or themselves [12]. Conversely, the culture of secrecy around sexual behaviors can create a lack of comfort, acceptance, transparency, and understanding [43]. Indeed, the incorporation of conversations regarding sexual health during childhood is essential to develop healthy sexual skills and behaviors [105, 106]. Those who are raised in religious communities where such conversations are overlooked or deemed inappropriate thus are more likely to feel anxious regarding sexuality as they lack appropriate information and understanding regarding sex [12]. This may be particularly true for LGBTQ + individuals, who are often raised in environments where coreligionists teach that sexual behaviors are only appropriate when between a cisgender man and a cisgender woman [107]. LGBTQ + individuals may thus be more susceptible to sex anxiety, as they face additional messages regarding the immorality of same-gender sexual behaviors [108] and less information regarding sexual health for people with minoritized sexual and gender identities [109] Although less common, some religious communities offer large support networks where members have access to sexual education and sexual health resources [110].

Guilt and Shame Surrounding Sex

Guilt and shame are commonly experienced emotional responses to sexuality, particularly among religious individuals [111]. Guilt and shame are social emotions and in this way are typically learned responses to perceived transgressions, where individuals who act against a religious norm feel guilty for “doing a bad thing,” or feel shame for “being a bad person.” Religious belonging thus leads to feelings of guilt and shame, as coreligionists often utilize religious doctrines or communal norms and morals to tell others that sexual behaviors are immoral and those who engage in such behaviors are bad people. Guilt is a more common byproduct of the tension between sexual needs/desires and religious doctrines that sexual activity should be limited to heterosexual marriage and for procreative purposes [112]. Conversely, religious people report more shame than guilt surrounding sexual behaviors and attitudes, noting that they felt they could justify sexual behaviors with a higher power but not with their coreligionists [113]. Women tend to experience more guilt and shame than men [71], as religious men tend to be more permissive about sex and religious women often face sexual double standards from coreligionists and are more highly encouraged to focus on abstinence [114]. Apart from feeling uncomfortable, shame and guilt also impact sexuality as they lead to reduced sexual satisfaction and well-being [111, 112]. See Table 1 for a summary of the major takeaways.

Conclusions

Religious belief, behaviors, and belonging are all inextricably linked with sexual health. Often, they exert overlapping or supportive effects (e.g., religious belief influences engagement with behaviors, religious belonging supports religious belief), but each operates along slightly different mechanistic pathways. Religious beliefs tend to describe the parameters around sexual conduct as well as the ways in which sexual conduct may be particularly meaningful. Religious behavioral proscriptions tend to focus on reducing both targeted sexual behaviors and sexual behaviors generally. Religious belonging tends to reinforce norms and provide support. Religiousness ultimately promotes and hinders sexual health, often simultaneously within the same person. Further, religiousness may continue to influence the sexual health of people who are no longer religious either through the early formation of their sexual schemas or through larger cultural and norm-based enforcement of conservative sexual behaviors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

•• World Health Organization. Sexual health. World Health Organization. 2024; https://www.who.int/health-topics/sexual-heathThis website defines sexual health and describes major trends happening in the area

Harris KA, Howell DS, Spurgeon DW. Faith concepts in psychology: Three 30-year definitional content analyses. Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2018;10(1):1–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000134.

• Saroglou V. Believing, bonding, behaving, and belonging: the big four religious dimensions and cultural variation. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 2011;42(8):1320-1340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022111412267. This piece lays out a framework for understanding the dimensions of religiousness.

• Smidt CE. Measuring religion in terms of belonging, beliefs, and behavior. Oxford Res Encycl Polit.2019; https://doi.org/10.1093/ACREFORE/9780190228637.013.675. This piece also lays out a framework for understanding the dimensions of religiousness.

•• Lefevor GT, Etengoff C, Davis EB, Skidmore SJ, Rodriguez EM, McGraw JS, Rostosky SS. Religion/spirituality, stress, and resilience among sexual and gender minorities: the religious/spiritual stress and resilience model. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2023;18(6):1537-1561. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916231179137This piece presents a model for understanding the influence of religiousness among LGBTQ+ people.

Lefevor GT, Davis EB, Paiz JY, Smack ACP. The relationship between religiousness and health among sexual minorities: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2021;147(7):647–66. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000339.

Ashdown BK, Hackathorn J, Clark EM. In and out of the bedroom: Sexual satisfaction in the marital relationship. J Integr Soc Sci. 2011;2(1):40–57. Retrieved from https://www.jiss.org/documents/volume_2/issue_1/JISS_2011_Sexual_Satisfaction_in_Marriage.pdf. Accessed 30 Apr 2024.

Davidson CR, Turner-McGrievy GM, Hilfinger Messias DK, Friedman DB, Robillard AG. A pilot study examining religious organization affiliation, sexual health information sources, and sexual behaviors among college students. Am J Sex Educ. 2019;14(1):32–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2018.1518176.

Patton MS. Masturbation from Judaism to Victorianism. J Relig Health. 1985;24(2):133–146. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27505821. Accessed 30 Apr 2024.

Fetner T, Andrejek N, Bird M, Werger M. Christian religious identity and sexual behaviour in Canada today. Can J Hum Sex. 2023;32(2):141–50. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2022-0014.

Azim KA, Happel-Parkins A, Moses A, Haardoerfer R. Exploring relationships between genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder, sex guilt, and religiosity among college women in the U.S. J Sex Med. 2021;18(4):770–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.02.003.

Jayne A, Koch JM, Federici DJ. Predictors of sex anxiety: Emphasis on religion in childhood, religious values, and family communication. Sex Cult. 2020;25(2):525–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09781-x.

Sanghvi P, Tripathi R. Role of religiosity in sexual cognition. J Indian Acad Appl Psychol. 2023;49(2):349–56.

Woo JST, Morshedian N, Brotto LA. Sex guilt mediates the relationship between religiosity and sexual desire in east Asian and Euro-Canadian college-aged women. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(6):1485–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9918-6.

Van Vo T, Hoang HD, Thanh Nguyen NP. Prevalence and associated factors of erectile dysfunction among married men in Vietnam. Front Public Health. 2017;5:219007. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00094.

Saleh DA, Karuri GS, Dagona ZK, Madu R, James A, Yabal J, ... Saleh TD. Role of religious devotion and marriage duration on sexual dysfunction among married women within Jos Metropolis: implications for couple/marital therapy in Nigeria. Int J Psychother Afr. 2022;7(1).

Thorpe S, Nichols TR, Tanner AE, Kuperberg A, Payton Foh E. Relational and partner-specific factors influencing black heterosexual women’s initiation of sexual intercourse and orgasm frequency. Sex Cult. 2021;25:503–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09780-y.

Happel-Parkins A, Azim KA, Moses A. “I just beared through it”: Southern US Christian women’s experiences of chronic dyspareunia. J Women’s Health Phys Ther. 2020;44(2):72–86. https://doi.org/10.1097/JWH.0000000000000158.

Patanwala I, Lamvu G, Mizera M, Fisk M, Blanton E. Learning restrictive sexual values may be associated with dyspareunia. J Endometriosis Pelvic Pain Disord. 2020;12(2):61–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2284026519900108.

Çankaya S, Aslantaş BN. Determination of sexual attitude, sexual self-consciousness, and sociocultural status in women with and without lifelong Vaginismus: a case-control study. Clin Nurs Res. 2022;31(7):1340–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/10547738221103334.

McEvoy M, McElvaney R, Glover R. Understanding vaginismus: a biopsychosocial perspective. Sex Relationsh Ther. 2021;1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2021.2007233

de M Silva AC, Sei MB, de A P Vieira RB. Family, religion, and sex education among women with vaginismus: a qualitative study. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática. 2021;23(3):1–24. https://doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPCP13276

Géonet M, De Sutter P, Zech E. Cognitive factors in women hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Sexologies. 2013;22(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2012.01.011

Ziaee P, Shamloo ZS, Mashhadi A, Shareh H. What is going on inside me? Lived experience of married women exhibiting hypoactive sexual desire disorder in long-term relationships: a qualitative study. J Fundam Mental Health. 2022;24(5). https://doi.org/10.22038/jfmh.2022.20994.

Clarke RW, Leavitt CE, Allsop DB, Marks LD, Dollahite DC. How sexuality and religion intersect in highly religious families: Implications for clinicians. Sex Relatsh Ther. 2021;37(3):342–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2021.2014052.

Dale B. Using spiritual discernment to heal clients wounded by religiously repressive sexual beliefs. Sex Relatsh Ther. 2022;37(3):476–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2021.2014445.

Fong TW, Reid RC, Parhami I. Behavioral addictions: where to draw the lines? Psychiatr Clin. 2012;35(2):279–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2012.03.001.

Borgogna NC, Johnson DAL, Shegedin M, Brasil KM. Taking another look at the pornography problems due to moral incongruence model: does gender play a role? Arch Sex Behav. 2024;53(2):703–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02743-y.

Coleman E, Jennings T, Gleason N, Danielson S, Nielsen KH, Miner MH, Rahm-Knigge RL. The relationship between compulsive sexual behavior, religiosity, and moral disapproval. J Sex Marital Ther. 2023;49(3):314–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2022.2117746.

Efrati Y. God, I can’t stop thinking about sex! the rebound effect in unsuccessful suppression of sexual thoughts among religious adolescents. J Sex Res. 2019;56(2):146–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1461796.

Levin ME, Lee EB, Twohig MP. The role of experiential avoidance in problematic pornography viewing. Psychol Rec. 2019;69:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-018-0302-3.

Twohig MP, Crosby JM, Cox JM. Viewing internet pornography: For whom is it problematic, how, and why? Sex Addict Compuls. 2009;16:253–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720160903300788.

Grubbs JB, Kraus SW, Perry SL, Lewczuk K, Gola M. Moral incongruence and compulsive sexual behavior: Results from cross-sectional interactions and parallel growth curve analyses. J Abnorm Psychol. 2020;129(3):266–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000501.

Kürbitz LI, Briken P. Is compulsive sexual behavior different in women compared to men? J Clin Med. 2021;10(15):3205. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10153205.

•• Floyd CG, Grubbs JB. Context matters: How religion and morality shape pornography use effects. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2022;14(1):82-98.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-022-00329-8This piece describes the recent research related to religiousness and porn use.

Grubbs JB, Stauner N, Exline JJ, Pargament KI, Lindberg MJ. Perceived addiction to internet pornography and psychological distress: examining relationships concurrently and over time. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29(4):1056–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000114.

Grubbs JB, Reid RC, Bothe B, Demetrovics Z, Coleman E, Gleason N, … Kraus S. Assessing compulsive sexual behavior disorder: The development and international validation of the compulsive sexual behavior disorder-diagnostic inventory (CSBD-DI). J Behav Addict. 2023;12(1):242–260. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2023.00005

Sorrell SA, Lefevor GT, Skidmore SJ, Golightly RM, Searle KNL. Understanding how religiousness shapes perceptions of compulsive sexual behavior. J Sex Marital Ther. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2024.2353221.

Neves S. The religious disguise in “sex addiction” therapy. Sex Relatsh Ther. 2022;37(3):299–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2021.2008344.

Dillon A. Bible journaling as a spiritual aid in addiction recovery. Religions. 2021;12(11):965. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110965.

Perry SL. Not practicing what you preach: religion and incongruence between pornography beliefs and usage. J Sex Res. 2018;55(3):369–80.

Hastings HF, Lucero Jones R, Dutton C. Women’s experience with religion and spirituality when perceiving their husband’s pornography use as problematic: a qualitative study. J Soc Pers Relat. 2024;41(4):730–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075231213610.

McKiernan DM, Clawson KG, Eddy BP. From secrecy to openness: sexual satisfaction in couples from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Sex Relatsh Ther. 2022;37(3):377–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2022.2047643.

Sungur MZ, Bez Y. Cultural factors in the treatment of sexual dysfunction in Muslim clients. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2016;8:57–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-016-0068-z.

Lindberg LD, Kantor LM. Adolescents’ receipt of sex education in a nationally representative sample, 2011–2019. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70(2):290–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.08.027.

Kandahari N, Prata N, Lahiff M, Abboud S. Family sex communication, parental acculturation, and religiosity among Arab American Young Adults. Sex Cult. 2023;27(5):1777–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023-10089-9.

Navarro-Prado S, Tovar-Gálvez MI, Sánchez-Ojeda MA, Luque-Vara T, Fernández-Gómez E, Martín-Salvador A, Marín-Jiménez AE. Type of sex education in childhood and adolescence: influence on young people’s sexual experimentation, risk and satisfaction: the necessity of establishing school nursing as a pillar. Healthcare. 2023;11(12):1668. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121668.

Alomair N, Alageel S, Davies N, Bailey JV. Factors influencing sexual and reproductive health of Muslim women: a systematic review. Reprod Health. 2020;17(33). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-0888-1

Fahey KM, Holm AK, Dermody SS. The moderating role of sexual orientation in the association between religiosity and sexual behaviors among college students. Arch Sex Behav. 2023;53(1):307–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02678-4.

Piper KN, Lambert DN, Fuller TJ. The impact of religious participation and religious upbringing on the sexual behavior of emerging adults in the Southern United States. Sex Cult. 2022;26(5):1711–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-022-09965-7.

Mark ND, Wu LL. More comprehensive sex education reduced teen births: Quasi-experimental evidence. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2022;119(8). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2113144119

Tabaac AR, Johns MM, Zubizarreta D, Haneuse S, Tan ASL, Austin SB, Potter J, Lindberg L, Charlton BM. Associations between sexual orientation, sex education curriculum, and exposure to affirming/disaffirming LGB content in two US-based cohorts of adolescents. Sex education. 2023;23(5):506–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2022.2072286.

Pampati S, Johns MM, Szucs LE, Bishop MD, Mallory AB, Barrios LC, Russell ST. Sexual and gender minority youth and sexual health education: a systematic mapping review of the literature. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68(6):1040–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.032.

Meyrick J, Anning A. Exploring the experiences of sexual violence/abuse survivors attending a recovery group: A qualitative study of recovery and evaluation implications. Violence Against Women: Advance online publication; 2023. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012231202999.

Oosterhoff P, Saxena S, Prankumar SK, Aggleton P. Survivor strategies: rebuilding intimate relationships and sexual wellbeing following sexual violence. Cult Health Sex. 2023;25(12):1577–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2023.2272115.

Gezinski LB, Gonzalez-Pons KM, Rogers MM. “Praying does not stop his fist from hitting my face”: religion and intimate partner violence from the perspective of survivors and service providers. J Fam Issues. 2023;44(9):2504–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19830140.

Le Roux E, Valencia LC. “There’s no-one you can trust to talk to here”: churches and internally displaced survivors of sexual violence in Medellín, Colombia. Hervormde Teologiese Stud. 2019;75(4):1–10. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i4.5491.

Pertek S. Adaptive religious coping with experiences of sexual and gender-based violence and displacement. J Refug Stud. 2024;feae003. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feae003

Dworkin ER, Weaver TL. The impact of sociocultural contexts on mental health following sexual violence: a conceptual model. Psychol Violence. 2021;11(5):476. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000350.

Delker BC, Salton R, McLean KC, Syed M. Who has to tell their trauma story and how hard will it be? Influence of cultural stigma and narrative redemption on the storying of sexual violence. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0234201. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234201.

Howell KH, Thurston IB, Schwartz LE, Jamison LE, Hasselle AJ. Protective factors associated with resilience in women exposed to intimate partner violence. Psychol Violence. 2018;8(4):438–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000147.

Eytan S, Ronel N. From looking for reason to finding meaning: A spiritual journey of recovery from sexual trauma. J Interpers Violence. 2023;38(11/12):7404–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221145723.

Pertek S, Block K, Goodson L, Hassan P, Hourani J, Phillimore J. Gender-based violence, religion and forced displacement: protective and risk factors. Front Human Dyn. 2023;5:1058822. https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2023.1058822.

Walker HE, Wamser-Nanney R, Howell KH. Relationships between childhood interpersonal trauma, religious coping, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and resilience. J Interpersonal Violence. 2022;37(13–14). https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260521991883

Frazier P, Tennen H, Gavian M, Park C, Tomich P, Tashiro T. Does self-reported posttraumatic growth reflect genuine positive change? Psychol Sci. 2009;20(7):912–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02381.x.

Kirkner A, Ullman SE. Sexual assault survivors’ post-traumatic growth: Individual and community-level differences. Violence Against Women. 2020;26(15–16):1987–2003. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801219888019.

Dew JP, Uecker JE, Willoughby BJ. Joint religiosity and married couples’ sexual satisfaction. Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2020;12(2):201–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000243.

Hackathorn JM, Ashdown BK, Rife SC. The sacred bed: Sex guilt mediates religiousness and satisfaction for unmarried people. Sex Cult. 2016;20:153–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-015-9315-0.

Hernandez-Kane KM, Mahoney A. Sex through a sacred lens: Longitudinal effects of sanctification of marital sexuality. J Fam Psychol. 2018;32(4):425. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000392.

Leonhardt ND, Busby DM, Hanna-Walker VR, Leavitt CE. Sanctification or inhibition? Religious dualities and sexual satisfaction. J Fam Psychol. 2021;35(4):433–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000796.

Leonhardt ND, Busby DM, Willoughby BJ. Sex guilt or sanctification? The indirect role of religiosity on sexual satisfaction. Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2020;12(2):213. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000245.

Leonhardt ND, Clarke RW, Leavitt CE. Religiosity, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: the moderating role of sexual mindfulness and sexual sanctification. J Sex Marital Ther. 2022;49(2):155–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623x.2022.2080132.

Kusner KG, Mahoney A, Pargament KI, DeMaris A. Sanctification of marriage and spiritual intimacy predicting observed marital interactions across the transition to parenthood. J Fam Psychol. 2014;28(5):604. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036989.

Ortiz A, Hall MEL, Anderson TL, Muehlhoff JM. Marital status at first intercourse in married christian women: relationships with guilt, sanctification of sexuality, and marital satisfaction. J Psychol Theol. 2022;50(4):444–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/00916471211028914.

Abbott DM, Harris JE, Mollen D. The impact of religious commitment on women’s sexual self-esteem. Sex Cult. 2016;20:1082. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-016-9374-x.

McFarland MJ, Uecker JE, Regnerus MD. The role of religion in shaping sexual frequency and satisfaction: evidence from married and unmarried older adults. J Sex Res. 2011;48(2–3):297–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224491003739993.

Peri-Rotem N, Skirbekk V. Religiosity, sex frequency, and sexual satisfaction in Britain: evidence from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). J Sex Res. 2023;60(1):13–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2022.2108745.

Moore TJ, Rose A, Skipper A, McKnight E. Sexual sanctification and relationship satisfaction in Black heterosexual couples. J Sex Marital Ther. 2024;1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2024.2329077

Sorrell SA. Shame-proneness and sexual satisfaction among conservatively religious sexual minorities. All Graduate Theses and Dissertations, Spring 1920 to Summer 2023. 2022;8679. https://doi.org/10.26076/a0a0-ab2c

Afrashteh S, Abbasi-Ghahramanloo A, Vali M, Ghaem H, Mohammadbeigi A, Tabatabaee H, Kargarian-Marvasti S. Risky sexual behavior among Iranian university students and its relationship with religiosity and familial support. Family Med Primary Care Rev. 2020;22(4):319–24. https://doi.org/10.5114/fmpcr.2020.100428.

Churchill SA, Appau S, Ocloo JE. Religion and the risks of sexually transmissible infections: evidence from Britain. J Relig Health. 2021;60:1613–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01239-0.

Francis JM, Myers B, Nkosi S, Petersen Williams P, Carney T, Lombard C, Nel E, Morojele N. The prevalence of religiosity and association between religiosity and alcohol use, other drug use, and risky sexual behaviours among grade 8–10 learners in Western Cape, South Africa. PLoS One. 2019;14(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211322

Busby DM, Bluhm J, Leonhardt ND. Relationship context, body-esteem, religiosity, and sexual experience: associations with well-being and relationship status. Am J Fam Ther. 2020;48(5):462–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2020.1745719.

Hall SS, Fox KM, Knox D, Kuck D. Young adults’ relationship beliefs and sexual behavior: the intersection of religion, race, and sexual identity. Sex Cult. 2020;24(5):1443–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09700-9.

Etengoff C, Lefevor GT. Sexual prejudice, sexism, and religion. Curr Opin Psychol. 2021;40(1):45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.08.024.

Armstrong J, Thorpe S, Williams D. Sexual attitudes, religious commitment, and sexual risk behaviors among college-aged women. J Gend Stud. 2020;30(8):875–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2020.1838888.

Dalmida SG, Aduloju-Ajijola N, Clayton-Jones D, Thomas Erazo TL, Toscano RJ, Lews R, Fleming T, Taylor S, Lunyong M. Sexual risk behaviors of African American adolescent females: the role of cognitive and religious factors. J Transcult Nurs. 2016;29(1):74-83https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659616678660

Hayward GM. Religiosity and premarital sexual behaviors among adolescents: an analysis of functional form. J Sci Study Relig. 2019;58(2):439–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12588.

Koletić G, Jurković L, Tafro A, Milas G, Landripet I, Štulhofer A. A meta-analytic exploration of associations between religious service attendance and sexual risk taking in adolescence and emerging adulthood. J Health Psychol. 2023;28(12):1103–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591053231164542.

de Costa MIL, Rocha AP, Jerónimo MAD, Gaspar P, de Luz AMB, Moleiro P. Religiousness and sexual behavior in young. Braz J Health Rev. 2023;6(5):22986–99. https://doi.org/10.34119/bjhrv6n5-320.

Hanna-Walker V, Walters TL, Wesche R, Leavitt CE, Lefkowitz ES. Religiosity, sexual behaviors, sexual motivations, and gender: a three-year longitudinal study. J Res Adolesc. 2023;33(3):943–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12849.

Bridges JG, Lefevor GT, Schow RL. Sexual satisfaction and mental health in mixed-orientation relationships: a Mormon sample of sexual minority partners. J Bisexuality. 2019;19(4):515–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2019.1669252.

Lefevor GT. Sexuality, religiousness, and mental health among sexual minority Latter-day Saints in other-gender relationships. J Sex Marital Ther. 2023;49(8):1013–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2023.2237957.

Lefevor GT, Beckstead AL, Schow RL, Raynes M, Mansfield TR, Rosik CH. Satisfaction and health within four sexual identity relationship options. J Sex Marital Ther. 2019;45(5):355–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623x.2018.1531333.

Lefevor GT, Schow RL, Beckstead AL, Raynes M, Young NT, Rosik CH. Domains related to single/relationship status satisfaction among sexual minorities raised conservatively religious. Spiritual Clin Pract. 2021;8(2):112–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000237.

Lefevor GT, Sorrell SA, Kappers G, Plunk A, Schow RL, Rosik CH, Beckstead AL. Same-sex attracted, not LGBQ: The implications of sexual identity labelling on religiosity, sexuality, and health among Mormons. J Homosex. 2020;67(7):940–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1564006.

Rosik CH, Lefevor GT, Beckstead AL. Sexual minorities who reject an LGB identity. Issues Law Med. 2021;36(1):27–43.

de BernardinGonçalves JP, Lucchetti G, de Oliveira Maraldi E, Fernandez PEL, Menezes PR, Vallada H. The role of religiosity and spirituality in interpersonal violence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Psychiatry. 2023;45(2):162–81. https://doi.org/10.47626/1516-4446-2022-2832.

Jirek SL, Truscott P. Geographical variation in the relationship between religiosity and campus sexual assault: differences in prevalence or reporting? Soc Work Christ. 2020;47(4):45–70. https://doi.org/10.34043/SWC.V47I3.140.

Robertson TM, Magyar-Russell GM, Piedmont RL. Let him who is without sin cast the first stone: religious struggle among persons convicted of sexually offending. Religions. 2020;11(11):546. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11110546.

Barnett MD, Sligar KB, Wang CD. Religious affiliation, religiosity, gender, and rape myth acceptance: feminist theory and rape culture. J Interpers Violence. 2018;33(8):1219–35.

Samson AT. Sexual coercion in the context of a marriage (Doctoral dissertation, Roosevelt University). Chicago, IL. 2022.

Garcia JR, Kruger DJ. Unbuckling in the Bible Belt: conservative sexual norms lower age at marriage. J Soc Evol Cult Psychol. 2010;4(4):206–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099288.

Sands K. God forbid: Religion and sex in American public life. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000.

Luker K. When sex goes to school: Warring views on sex—and sex education—since the sixties (1st ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co.; 2006.

Bruess C, Schroeder E. Sexuality education: Theory and practice (6th ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2014.

Gerdts DD. The religious landscape for LGBTQ+ persons. Del J Pub Health. 2019;5(3):68–72. https://doi.org/10.32481/djph.2019.06.012.

Zarzycka B, Rybarski R, Silwak J. The relationship of religious comfort and struggle with anxiety and satisfaction with life in Roman Catholic Polish men: the moderating effect of sexual orientation. J Relig Health. 2017;56(6):162–2179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0388-y.

Skidmore SJ, Lefevor GT, Larsen ER, Golightly RM, Abreu RL. “We are scared of being kicked out of our religion!”: common challenges and benefits for sexual minority latter-day saints. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2023;10(4):663–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000571.

Puffer ES, Green EP, Sikkema KJ, Broverman SA, Ogwang-Odhiambo RA, Pian J. A church-based intervention for families to promote mental health and prevent HIV among adolescent sin rural Kenya: results of a randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84(6):511–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000076.

Mróz J, Kaleta K, Bernacka RE, Kubrak K, Weryszko M, Charzyńska E. Religiosity and sexual satisfaction in middle age: the moderating role of nonconformity. Religions. 2023;14(3):377. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030377.

Wacks Y, Lazar A, Sommerfeld E. The moderating effect of religiousness on the relation between sexual guilt and shame and well-being among Jewish religious single men. Arch Sex Behav. 2022;52(4):1549–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02494-2.

Deguara A. Sexual morality and shame among Catholics whose lifestyle does not conform to Church teaching. Sex Cult. 2019;23(3):793–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09591-w.

Estrada LL. Clinical considerations of the Evangelical Purity Movement’s impact on female sexuality. J Sex Marital Ther. 2021;48(2):121–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623x.2021.1977445.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dru Martin and Ella Wallace for their help in conducting the literature search that helped inform this review

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All three authors worked collaboratively on the conceptualization, initial manuscript writing, and revisions. TL took the lead on organizing the manuscript, streamlining edits, references, and creating the figure.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lefevor, G.T., Sorrell, S.A. & Skidmore, S.J. How and Why Religiousness Influences Sexual Health: a Review. Curr Sex Health Rep 16, 185–194 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-024-00390-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-024-00390-5