Abstract

Research has examined the relationship between religiosity and sexuality but few studies have explored the mechanisms by which sexual variables are influenced by religiosity. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the role of sex guilt in the relationship between religiosity and sexual desire in women. Euro-Canadian (n = 178) and East Asian (n = 361) female university students completed a battery of questionnaires. Higher levels of religious fundamentalism, intrinsic religiosity and spirituality were associated with higher levels of sex guilt in both ethnic groups. Paranormal belief was not associated with sex guilt in either ethnic group. The Euro-Canadian women reported significantly higher levels of sexual desire and significantly less sex guilt than the East Asian women. Among the Euro-Canadian women, sex guilt mediated the relationships between spirituality and sexual desire, and fundamentalism and sexual desire; among the East Asian women, sex guilt mediated the relationships between spirituality and sexual desire, fundamentalism and sexual desire, and intrinsic religiosity and sexual desire. These findings suggest that sex guilt may be one mechanism by which religiosity affects sexual desire among women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sex is a sphere of human behavior high in religious applicability and, throughout history, religion has regulated sexual behavior (Regnerus, 2007). Indeed, sex is considered a topic that has more religious relevance and is more clearly addressed in most religious traditions than many other topics (Regnerus, 2007). Most, if not all, of the world’s major religions designate what constitutes virtuous or acceptable sexual activity for their adherents (Ahrold, Farmer, Trapnell, & Meston, 2011; Cowden & Bradshaw, 2007). For example, with the possible exception of Buddhism, most religions condemn premarital and extramarital sex (Miracle, Miracle, & Baumeister, 2003). However, whereas individuals’ social, cultural, and moral identities were once strongly tied to religion, there has been a significant increase in the percentage of Americans who report no religious affiliation since the 1960s (Putnam & Campbell, 2010; Stark & Bainbridge, 1985). Moreover, since some religions are more present in certain cultural groups, recent research has also found that sexuality is influenced by the interaction of culture and religion (e.g., Ahrold & Meston, 2010; McCree, Wingood, DiClemente, Davies, & Harrington, 2003). As a result, any direct effect of religion on sexuality has become less clear (Farmer, Trapnell, & Meston, 2009). Researchers have observed that there is as much diversity in religiosity within religious groups as there is between groups; thus, consideration of individual differences in religiosity is essential to improve the understanding of the effects of religion on sexuality (Ahrold et al., 2011; Cowden & Bradshaw, 2007).

Religiosity can be defined as the role and importance of religion in one’s life (Cowden & Bradshaw, 2007). Despite advances in research into the relationship between religiosity and sexuality, the specific mechanisms by which religiosity affects sexuality have received little empirical attention and are not well-delineated. The purpose of the current study was to investigate the potential role that sex guilt may play in the relationship between religiosity and sexual desire.

The relationship between religion and various aspects of sexuality has been a subject of scientific study since the early days of sex research. In their classic work, Human Sexual Inadequacy, Masters and Johnson (1970) examined differences in sexual arousal, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain in relation to religious upbringing. They found that a strict religious upbringing in Judaism, Catholicism, and Protestantism was associated with different types of sexual dysfunction, including impotence (i.e., erectile dysfunction), anorgasmia, and vaginismus. More recent research on the influence of religion on sexuality has found that non-religious individuals report more sexual experiences and greater frequency of masturbation than those individuals who identify as Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish (Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994; Leiblum, Wiegel, & Brickle, 2003; Pluhar, Frongillo, Stycos, & Dempser-McClain, 1998). More frequent religious service attendance has been found to be associated with greater sexual abstinence, less sexual activity, less frequent sexual intercourse, fewer lifetime sexual partners, and older age at first intercourse (Barkan, 2006; Cochran & Beeghley, 1991). With regard to sexual attitudes, more frequent religious attendance has been linked to more conservative attitudes toward premarital sex as well as more negative attitudes toward oral and anal sex (Ahrold et al., 2011; Davidson, Moore, & Ullstrup, 2004). Those who attend religious services weekly were also more likely to cite love as a prerequisite for engaging in intercourse, to want to marry a virgin, and to want to marry someone who had not previously had sexual intercourse (Davidson et al., 2004). Whether religiosity is associated with sexual dysfunction has never been tested.

Measures such as frequency of religious service attendance implicitly assume that frequent attendance denotes greater religiosity. The use of such attendance as an indicator of religiosity across faith groups is problematic, as members of religious affiliations differ dramatically in their expectations of participation in formal religious services. For example, one study of Australian adults found that more frequent religious service attendance was generally linked to more conservative sexual attitudes and behaviors, but religious individuals who seldom attended services resembled their non-religious peers more than their more religious counterparts (de Visser, Smith, Richters, & Rissel, 2007). This measure (i.e., religious attendance) seems to be biased towards members of Christian denominations who are expected to attend church services weekly or sometimes daily, and does not take into account the religious practices of Muslims who are expected to pray several times a day, or Buddhists who are not expected to attend formal services regularly (Welwood, 2000). Furthermore, the use of religious attendance as a proxy for religiosity does not capture specific attitudes and motivations that are associated with religiosity nor does it consider external influences, such as the social influence of peers and family, which can affect religious attendance but which may not necessarily affect religiosity in the same manner (Kirkpatrick & Hood, 1990). Kinsey, Pomeroy, and Martin (1948) were the first to suggest that variation in devoutness within religious groups was more important than religious affiliation per se in determining patterns of sexual behavior, such as masturbation to orgasm, premarital petting, and premarital sex. Therefore, conclusions drawn about the relationship between religion and sexuality that are based on the use of religious affiliation or attendance as a proxy for religiosity should be viewed with caution.

By studying other domains of religiosity, including intrinsic religiosity, spirituality, religious fundamentalism, and paranormal belief, this may provide more clarity on the relationship between religiosity and sexuality. Specifically, they provide a richer picture of the influence of religion in individuals’ lives.

Intrinsic Religiosity

Intrinsic religiosity refers to the individual’s perception of the impact of religion in their daily life and has been conceptually associated with personal religious commitment, as opposed to the more socially visible aspects of religiosity, such as religious service attendance (Donahue, 1985; Kirkpatrick & Hood, 1990). Adherents of Buddhism and Christianity may consider themselves to be equally devout, but this would not be apparent in a measure of religious service attendance as there is no explicit requirement in Buddhism that devotees attend religious services regularly. Instead, measuring intrinsic religiosity directly promotes a more comprehensive understanding of religiosity.

Research has found a link between intrinsic religiosity and sexual conservatism such that greater intrinsic religiosity is associated with more conservative sexual attitudes in both men and women (Ahrold et al., 2011) and with less openness towards casual sexual encounters and motivation to pursue casual sexual partners among women (Rowatt & Schmitt, 2003). Interestingly, the effect of intrinsic religiosity on sexual conservatism was found even in a sample of individuals identifying with religious groups whose religious practices varied in terms of performance of formalized rituals and expectations of attendance at formal religious services (Ahrold et al., 2011). This suggests that intrinsic religiosity as a construct may be relevant across members of various religious groups regardless of their religious service attendance.

Spirituality

Whereas intrinsic religiosity is an indicator of the impact of religion on one’s daily life, spirituality connotes an internalized subjective experience of belief in a divine or sacred being or force (Zinnbauer, Pargament, & Scott, 1999). Like intrinsic religiosity, however, greater spirituality was associated with more conservative sexual attitudes as well as more conservative attitudes toward specific sexual practices (Beckwith & Morrow, 2005). Spirituality has also been linked to voluntary sexual activity such that greater spirituality was associated with a lower likelihood of ever having engaged in voluntary sexual activity in urban youth (Holder et al., 2000).

Religious Fundamentalism

Religious fundamentalism is another area of religiosity that has been studied by researchers in sexuality. Fundamentalism refers to the belief that there exists only one correct religious doctrine that articulates the essential truth about humanity and deity, and that those whose attitudes and behaviors adhere strictly to this doctrine have a special relationship with the deity (Altemeyer & Hunsberger, 1992). Religious fundamentalism is distinct from intrinsic religiosity in that individuals who are high in fundamentalism regard religious dogma as the sole source of moral authority whereas those who are high in intrinsic religiosity may acknowledge other sources of faith, including traditions, rituals, and personal reasoning or interpretation (Hood, Spilka, Hunsberger, & Gorsuch, 1996). In general, greater fundamentalism is associated with more negative attitudes towards premarital sex (Bassett, Smith, Newell, & Richards, 1999), and more conservative attitudes towards homosexuality, casual sex, and gender role traditionality (Ahrold & Meston, 2010).

Paranormal Belief

With the rising influence of new-age religious and spiritual groups, research has pointed to the increasing need to study paranormal belief (Ahrold et al., 2011; Hirschman, 2004). Paranormal belief encompasses beliefs in supernatural phenomena both in traditionally religious contexts, such as belief in life after death or belief in angels and demons, and quasi-religious beliefs, such as superstitions (Irwin, 1993). Greater paranormal belief has been found to be associated with greater interest in pursuing short-term sexual partners (Weiss, Egan, & Figueredo, 2004). The investigators proposed that an affinity for “sensational interests,” of which the paranormal forms an element, may be one strategy in intrasexual competition for sexual partners. Knowledge of sensational information that implies familiarity with means of acquiring power may reflect qualities such as motivation and mental capacity, which may impress other same-sex individuals during contests of symbolic dominance. Thus, greater mating effort—the mating strategy of investing resources in the acquisition and guarding of many short-term sexual partner is hypothesized to be predictive of higher levels of sensational interests.

Regardless of one’s religious affiliation, everyone would be expected to embody the four domains of religiosity—intrinsic religiosity, spirituality, religious fundamentalism, and paranormal belief—to some extent. The current study expanded on past literature that has utilized a multidimensional measure of religiosity that assesses all four domains (e.g., Ahrold & Meston, 2010; Ahrold et al., 2011) and used this measure to examine the mechanisms by which the various domains of religiosity influence sexual desire in women.

In studying the effects of religiosity on sexuality, it is also important to consider cultural influences. Some religions are more prevalent in some cultural groups and as culture is strongly linked to sexual attitudes, behaviors, knowledge, and function, it is crucial to take culture into account when attempting to understand religiosity influences on sexuality. In the research that has compared Western with Asian sexuality, Asians have consistently been found to possess less accurate sexual knowledge (Brotto, Chik, Ryder, Gorzalka, & Seal, 2005; Meston, Trapnell, & Gorzalka, 1998; Woo, Brotto, & Gorzalka, 2009) and report greater sexual conservatism (Ahrold & Meston, 2010; Higgins & Sun, 2007; Meston, Trapnell, & Gorzalka, 1996; Woo, Brotto, & Gorzalka, 2011a), more acceptance of sexual harassment (Kennedy & Gorzalka, 2002), and higher rates of sexual difficulties (Brotto et al., 2005; Woo et al., 2011a) compared to their Western counterparts. They also demonstrate a narrower repertoire of sexual behaviors (Meston & Ahrold, 2010; Meston et al., 1998; Woo et al., 2009).

Although a large body of research has detailed the dimensions along which Western and Asian sexuality differ, much less has been published about the mechanisms that underlie these cultural differences. In seeking to explain the cultural disparity in sexuality-related variables, most studies simply referred to general culture-linked differences in sexual conservatism although this had not been empirically investigated. A recent study of sexual desire differences among East Asian (Chinese, Japanese, Korean) and Euro-Canadian women, however, examined the roles of sex guilt and sexual conservatism in the relationship between ethnic group and sexual desire (Woo et al., 2011a). Sexual conservatism was conceptualized as self-imposed restrictions on various facets of sexuality, such as the appropriateness of specific sexual partners and sexual activities as well as contexts in which sexual activity was permissible. In contrast, sex guilt was defined as a personality disposition characterized by “a generalized expectancy for self-mediated punishment for violating or for anticipating violating standards of proper sexual conduct” (Mosher & Cross, 1971, p. 27). This study found that sexual conservatism and sex guilt separately mediated the relationship between ethnic group and sexual desire, in that women with higher sex guilt and those who were more sexually conservative reported lower sexual desire. On the other hand, among the East Asian women, sex guilt but not sexual conservatism mediated the relationship between degree of Westernization and sexual desire. As a result, it was concluded that sex guilt had greater utility than sexual conservatism in improving the understanding of cultural effects on sexual desire.

The role of sex guilt has also been explored in the religiosity literature. Although church attendance was used as a proxy for religiosity in this work, these studies represent important first steps toward improving the understanding of the relationship between sex guilt and religiosity. In a multiethnic sample of African American and Euro-American women, religiosity, as measured by church attendance, was a better predictor of sex guilt than ethnicity and socioeconomic status (Wyatt & Dunn, 1991). Using church attendance as a proxy for religiosity, Gunderson and McCary (1979) found that frequency of church attendance was linked to sex guilt, such that individuals who attended church more frequently also reported higher sex guilt, which, in turn, was predictive of more conservative sexual attitudes, less accurate sexual knowledge, and more restricted sexual activity. However, to our knowledge, the potential mediating role of sex guilt in the relationship between religiosity and sexuality-related variables has not received empirical attention.

The Present Study

The purpose of the current study was to improve the understanding of the role of sex guilt in explaining the relationship between religiosity and sexual desire as a first step towards accounting for the observed effects of religiosity on sexuality. We chose to study sexual desire because it is a construct that has been found to differ cross-culturally (e.g., Brotto et al., 2005; Woo et al., 2011a) and is sensitive to the influence of sex guilt (Woo et al., 2011a); however, it has never been explored with regard to religiosity. We speculated that the relationship between religiosity and sexual desire would be mediated by sex guilt such that higher religiosity would be predictive of greater sex guilt, and greater sex guilt would, in turn, be predictive of lower sexual desire. Based on our earlier finding that sex guilt mediated the relationship between ethnicity and sexual desire such that sex guilt played a more pronounced role in the East Asian group compared to a Euro-Canadian comparison group, we hypothesized here that sex guilt may mediate the relationship between religiosity and sexual desire more strongly among the East Asian compared to the comparison group.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from the psychology department’s human subject pool at a large Canadian university. East Asian (Chinese, Japanese, and Korean) and Euro-Canadian women who were fluent in English and at least 18 years of age were eligible to participate. A total of 549 women participated. Of these, 178 self-identified as Euro-Canadian and 361 self-identified as East Asian. The remaining 10 participants self-identified as other ethnic groups or mixed ethnicity and were excluded from further analyses. Information on religious group was collected with the open-ended question “What is your religion?” Demographic data, including religious group, are shown in Table 1.

Measures

Demographics Questionnaire

An investigator-derived questionnaire assessing demographic variables, sexual intercourse history, and experience with a variety of different types of sexual activity was administered.

Religiosity Measures

Participants rated their religiosity on all four measures on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), with some items reverse scored. Higher scores indicate greater religiosity in each domain.

Paranormal Beliefs. Belief in paranormal phenomena, including supernatural powers and superstitions, was assessed using a 10-item scale developed by Trapnell (2005). An example of an item that comprises the paranormal beliefs measure is: “I’m very receptive to magical or supernatural experiences, rather than skeptical.” This measure has not been standardized, but internal consistency of the scale in a previous study was adequate (Cronbach’s α = .80; Farmer et al., 2009). Internal consistency in the current sample was good (Cronbach’s α = .85).

Spirituality

Spirituality was assessed with a questionnaire consisting of 8 items developed by Trapnell (2005). An example of an item that comprises the spirituality measure is: “I tend to think of myself as especially spiritually-oriented.” This measure has not been standardized, but internal consistency of the scale in two previous studies was acceptable (Cronbach’s α = .88) (Ahrold et al., 2011; Farmer et al., 2009) and in the current sample was good (Cronbach’s α = .91).

Intrinsic Religiosity

Intrinsic religiosity was measured using the intrinsic religiosity subscale of the Age Universal Religious Orientation Scale (Gorsuch & Venable, 1983). One item (“I enjoy reading about my religion”) was inadvertently left out of the version of the measure used in the current study because of mislabeling in the original publication. This resulted in an 8-item measure of intrinsic religiosity in the current study. An example of an item that comprises the intrinsic religiosity measure is: “It is important for me to spend time in private thought and prayer.” Internal consistency of this measure in the standardization sample ranged from .68 for children to .73 for adults. Internal consistency of this measure in the current study was good (Cronbach’s α = .93).

Fundamentalism

An abbreviated version of the Religious Fundamentalism Scale developed by Altemeyer and Hunsberger (1992) was used to measure religious fundamentalism. This short form version consisted of 10 items. An example of an item comprising the fundamentalism scale is: “To lead the best, most meaningful life, one must belong to the one, true religion.” This abbreviated version demonstrated good internal consistency in two prior studies (Cronbach’s α = .87; Ahrold et al., 2011; Farmer et al., 2009) as well as in the current sample (Cronbach’s α = .84).

Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)

The FSFI (Rosen et al., 2000) is a self-report questionnaire that consists of 19 items and assesses six domains of sexual functioning, including sexual desire, over the previous 4 weeks. Higher scores on each subscale indicated higher sexual functioning. In this study, only the desire domain, which consists of two items, was examined. The first question that comprises this domain is “Over the past 4 weeks, how often did you feel sexual desire or interest?” with responses ranging from “Almost never or never” to “Almost always or always.” The second question that comprises this domain is “Over the past 4 weeks, how would you rate your level (degree) of sexual desire or interest?” with responses ranging from “Very low or none at all” to “Very high.” Scores on this subscale ranged from 1 to 5. The FSFI has good psychometric properties, with high test–retest reliability (r = .83) as well as high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .92). Scores on the desire subscale may be meaningfully interpreted for women who are sexually active as well as those who are not (Brotto, 2009; Meyer-Bahlburg & Dolezal, 2007).

Revised Mosher Guilt Inventory (RMGI)

The RMGI (Mosher, 1988) is a self-report questionnaire that measures sex guilt, hostility guilt, and guilty conscience. For the purposes of the current study, only the 50 items that constitute the sex guilt subscale were administered. Participant responses were rated on a 7-point Likert scale that ranged from 0 (Not at all true for me) to 6 (Extremely true for me). Total scores on this subscale ranged from 0 to 300, with higher scores indicating higher sex guilt. Internal consistency in the current sample was high (Cronbach’s α = .96). The psychometric properties of earlier versions of the RMGI have been established by a number of studies (e.g., Abramson & Mosher, 1979; Ruma & Mosher, 1967), with convergent validity estimates ranging from 0.66 to 0.86.

Procedure

The study was publicized using the online experiment management system for the university’s human subject pool. Participants completed a battery of questionnaires in groups of 15-20 in a large testing room. Written informed consent was obtained and then questionnaires were administered by a female research assistant. Participants received extra course credit for their participation in this study. All procedures were approved by the university’s behavioral research ethics board.

Data Analysis

SPSS version 13 was used for all statistical analyses. T-tests were used in analyses comparing the two ethnic groups on various domains of religiosity, sex guilt, and sexual desire. In analyses of the association between ethnicity and sexual variables, the point-biserial statistic was used.

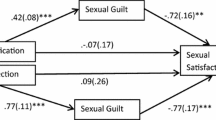

The bootstrap procedure for mediation analysis advocated by Shrout and Bolger (2002) was used in all mediation analyses because it has been suggested that bootstrap methods are more appropriate than more traditional approaches to mediation (e.g., Baron & Kenny, 1986) when the hypothesized mediation process is temporally distal, such as that between religiosity and sexual desire. Other advantages of the bootstrap method include not requiring the distribution of the indirect effect to meet the normality assumption, greater power, and better Type I error control (Hayes, 2009). Three thousand samples, with replacement, were used in each mediation analysis. All mediation analyses were conducted using an SPSS macro developed by Preacher and Hayes (2004) which sampled randomly with replacement from the dataset. The mediation model used in the current study is illustrated in Fig. 1.

A simple mediation model. a represents the effect of the initial variable X on the mediating variable M; b represents the effect of M on the outcome variable Y after controlling for the effect of X; and c and c’ represent the direct effect of X on Y, and the effect of X on Y after controlling for M, respectively. The bootstrap method does not require tests of a, b or c to demonstrate mediation; rather, a mediation effect is established when the product ab is significantly different from zero (Hayes, 2009)

Results

Ethnic Group, Religiosity, and Sexuality Measures

The two ethnic groups differed significantly on all sexual activities that were assessed in this study, including kissing, hugging, and holding hands; touching with clothing removed; touching of partner’s genitals; giving and receiving oral sex; and engaging in sexual intercourse (all ps < .001), with the Euro-Canadian women more likely to have engaged in each of these activities. In comparing the two ethnic groups on religiosity, sex guilt, and sexual desire, we adjusted for large family-wise error rate, applying a Bonferroni correction by dividing the standard alpha level of .05 by six (the number of comparisons being made). Thus, ethnic differences were considered statistically significant only if p < .008 (.05/6 comparisons). Comparisons between the two ethnic groups revealed significant differences in three of the religiosity measures- intrinsic religiosity, religious fundamentalism and paranormal belief—with the East Asian group scoring higher on each of these measures, indicating greater religiosity among the East Asian women in these domains (Table 2).

The Euro-Canadian women (M = 4.06, SD = 1.06) scored significantly higher on the FSFI Desire subscale, indicating greater sexual desire than the East Asian women (M = 3.29, SD = 1.18, t(526) = 7.25, p < .001; Cohen’s d = 0.69). With regard to sex guilt, the Euro-Canadian women (M = 65.86, SD = 37.48) scored significantly lower on the RMGI Sex Guilt subscale, indicating less sex guilt than the East Asian women, (M = 119.07, SD = 44.88, t(369) = −13.94, p < .001; Cohen’s d = −1.29). Because there were significant ethnic differences in both religiosity and sexual desire, subsequent analyses of religiosity effects on sex guilt and sexual desire were conducted separately for each ethnic group to avoid confounding the effects of ethnicity and religiosity.

There were significant positive correlations between scores on some of the religiosity measures and the RMGI in both ethnic groups. Among the East Asian women, the correlations between RMGI scores and scores on the measures of religious fundamentalism, r(334) = .51, p < .001, intrinsic religiosity, r(338) = .48, p < .001, and spirituality, r(337) = .34, p < .001, were significant. Similarly, among the Euro-Canadian women, the correlations between RMGI scores and scores on the measures of religious fundamentalism, r(159) = .62, p < .001, intrinsic religiosity, r(157) = .53, p < .001, and spirituality, r(160) = .39, p < .001, were significant.

There were also significant correlations among some of the religiosity measures in both ethnic groups. These correlations are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

The Mediating Role of Sex Guilt in the Relationship Between Religiosity and Sexual Desire

Among the Euro-Canadian women, sex guilt mediated the relationships between spirituality and sexual desire, and fundamentalism and sexual desire. For example, the effect of spirituality on sex guilt was demonstrated (β = 12.39, p < .001), indicating that higher spirituality was associated with significantly greater sex guilt. The effect of sex guilt on sexual desire, holding spirituality constant, was also significant (β = −.01, p < .01), showing that increased sex guilt was linked to less sexual desire. The indirect effect of spirituality on sexual desire, computed by multiplying the effect of spirituality on sex guilt with the effect of sex guilt on sexual desire while controlling for spirituality, was also significant (ab = −.09, SE = .03, CI95 = −.16, −.03). Hence, sex guilt mediated the relationship between spirituality and sexual desire. The complete results of the mediation analyses are presented in Table 5.

Among the East Asian women, mediation analyses revealed that sex guilt mediated the relationships between spirituality and sexual desire, fundamentalism and sexual desire, as well as intrinsic religiosity and sexual desire. For example, the indirect effect of spirituality on sexual desire, computed by multiplying the effect of spirituality on sex guilt with the effect of sex guilt on sexual desire while controlling for spirituality, was significant (ab = −.18, SE = .04, CI95 = −.26, −.11). Hence, sex guilt mediated the relationship between spirituality and sexual desire among the East Asian women. The complete results of these mediation analyses are presented in Table 6.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the potential mediating role of sex guilt in the link between religiosity and sexual desire in East Asian and Euro-Canadian women. The results of the analyses of ethnic differences in religiosity revealed that East Asian women scored higher than their Euro-Canadian counterparts on most of the religiosity measures and thus the effects of religiosity on sex guilt and sexual desire were analyzed separately for the two ethnic groups. Analyses of ethnic differences in sexual desire showed that the Euro-Canadian women reported higher levels of sexual desire and lower levels of sex guilt. These findings were consistent with the literature on ethnic differences in sexual response and sex guilt (Abramson & Imai-Marquez, 1982; Brotto et al., 2005; Cain et al., 2003; Laumann et al., 2005; Woo et al., 2010).

As expected, we found that, among the Euro-Canadian women, sex guilt mediated the relationship between spirituality and sexual desire, and between fundamentalism and sexual desire. Among the East Asian women, mediation analyses revealed that sex guilt mediated the relationships between spirituality and sexual desire, fundamentalism and sexual desire, as well as intrinsic religiosity and sexual desire. In both groups of women, higher levels of each measure of religiosity were associated with higher levels of sex guilt, which, in turn, were linked to lower levels of sexual desire. This is a novel finding because the specific mechanisms that underlie the association between religiosity and sexual desire have not received empirical attention.

Why does sex guilt mediate the relationship between religiosity and sexual desire? A more in-depth examination of the connection between sex guilt and religion may shed light on this question. As described earlier, Mosher and Cross (1971) conceived of sex guilt as a negatively-valenced emotion arising from the violation or anticipated violation of “standards of proper sexual conduct that may manifest itself by inhibited sexual behavior, or by the disruption of cognitive processes in sex-related situations.” Other than some sexual acts, such as incest and forced sexual relations (such as rape) which are almost universally prohibited, what constitutes acceptable sexual behaviors varies greatly between cultures and is often inextricably intertwined with religious tradition (Davidson et al., 2004; DeLamater, 1987). In Christianity, for example, the only sexual activity that is considered morally acceptable is heterosexual intercourse occurring within the context of a marital relationship and for the purpose of procreation (Curran, 1992). By extension, sexual activity for the purpose of sexual pleasure is considered sinful in many Christian denominations (Runkel, 1998). Thus, it is possible that clerical condemnation of other types of sexual activity, or sexual activity occurring in other contexts, may elicit guilty feelings relating to expressions of sexuality, with higher levels of religiosity being associated with higher levels of sex guilt. This was borne out in the current study as religious fundamentalism, intrinsic religiosity, and spirituality were significantly and positively correlated with sex guilt in both the Euro-Canadian and East Asian groups.

Interestingly, paranormal belief was not significantly correlated with sex guilt in either ethnic group. Although the reason for this is unclear based on the current study, one possibility could be that paranormal belief may be qualitatively different from the other three domains of religiosity that were examined in this study. Whereas all four domains of religiosity may reflect varying degrees of devoutness in relation to a major world religion, belief in paranormal phenomena in particular may also be pertinent to ethnocultural folk religions and new age quasi-religious groups. Although ethonocultural folk religions can be associated with major religions, they are often infused with beliefs such as that spirits of nature and souls of the dead are close by. These folk religions also frequently characterized by regular participation in rituals that are believed to bring good fortune and cure illness, as well as magical beliefs and animism. As these groups do not regulate sexuality in the same way that most of the major religions do, it may follow that higher levels of paranormal belief are not necessarily associated with greater sex guilt. This conjecture is consistent with a study that found that believers in traditional Chinese ethnocultural religions reported higher levels of paranormal belief compared to Christian individuals (Shiah, Tam, Wu, & Chang, 2010).

While sex guilt mediated the relationships between spirituality and fundamentalism with sexual desire in both groups, sex guilt mediated the relationship between intrinsic religiosity and sexual desire only in the East Asian women but not the Euro-Canadian group. This finding suggests that all aspects of religiosity impact desire through sex guilt for East Asian women whereas the impact of intrinsic religiosity on desire in Euro-Canadian women is not via sex guilt, but perhaps through other mechanisms. One potential interpretation of this finding is that the East Asian women were more influenced by the activation of sex guilt than were the Euro-Canadian women. It also highlights the fact that there is ethno-cultural variation in the mechanisms by which religion affects sexual desire. Future research should aim to explore other mechanisms by which religiosity influences sexuality and how such mechanisms differ by ethnic groups.

The finding that the relationship between various domains of religiosity and sexual desire is mediated by sex guilt may have implications for understanding the etiology and the treatment of low sexual desire in women. We chose to study sexual desire because it continues to be a great conundrum for sex researchers and therapists to define, understand, and adequately treat (Brotto, 2010). Specifically, sex guilt may underlie problems with low sexual desire among Euro-Canadian women who endorse high levels of spirituality and religious fundamentalism, and East Asian women who endorse high levels of spirituality, intrinsic religiosity and religious fundamentalism. To date, cognitive behavioral and couples counseling interventions have been commonly used in the psychological treatment of problems with low sexual desire. Although the scientific literature on treatment efficacy remains limited, the evidence suggests that these treatments are generally effective (Brotto, Basson, & Luria, 2008; Brotto, Bitzer, Laan, Leiblum, & Luria, 2010; Hawton, Catalan, & Fagg, 1991; Hurlbert, 1993; McCabe, 2001; Schover & LoPiccolo, 1982; Trudel et al., 2001). Given that the current study found that sex guilt may play a role in the sexual desire problems of highly religious women, it is possible that incorporating sex guilt as a treatment target in existing interventions may improve treatment outcome.

The current study has limitations that must be addressed. Firstly, the university sample was significantly younger than women in the general population, which limits the generalizability of our findings to the large population of treatment seekers who may be considerably older. This is of particular concern in this study because most of the women in our sample were unmarried and it is not possible to draw conclusions about the relationships among religiosity, sex guilt, and sexual desire in married women based on the current study. Given that sexual activity, and therefore sexual desire, within the marital relationship is acceptable in most major religions, it is especially important that future research examine the interrelationships among these variables in married individuals. Secondly, the use of a university sample does not allow for the consideration of other relevant interconnected factors that may relate to sex guilt, such as socioeconomic status and age. Data from a separate study indicate that there is a positive correlation between sex guilt and age, such that older age is associated with higher levels of sex guilt (Woo, Brotto, & Gorzalka, 2011b). Thirdly, because only women were included in the current study, it is not possible to determine the extent to which these findings would hold for men. Prior research indicates that there are significant sex differences in levels of sex guilt, with women consistently being found to have greater sex guilt than men (Abramson & Imai-Marquez, 1982; Abramson & Mosher, 1979; Plaud, Gaither, & Weller, 1998). Thus, the mechanism that underlies the relationship between religiosity and male sexual desire may differ from that found in women. Fourthly, sexual desire was measured with two items on a self-report questionnaire which may not capture the multidimensional and multi-determined nature of sexual desire. Finally, the social desirability of acknowledging high levels of sexual desire may vary with religiosity. Thus, it is possible that the relationship between religiosity and sexual desire may be accounted for by variations in social desirability rather than sex guilt.

In conclusion, novel to this study were the findings that religiosity is associated with lower levels of sexual desire, and that sex guilt mediates the relationship between a number of domains of religiosity and sexual desire in Euro-Canadian and East Asian women. These findings advance our understanding of the mechanisms by which religiosity influences sexual desire and may have implications for the assessment and treatment of low sexual desire in clinical practice.

References

Abramson, P. R., & Imai-Marquez, J. (1982). The Japanese-American: A cross-cultural, cross-sectional study of sex guilt. Journal of Research in Personality, 16, 227–237.

Abramson, P. R., & Mosher, D. L. (1979). An empirical investigation of experimentally induced masturbatory fantasies. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 8, 27–39.

Ahrold, T. K., Farmer, M. A., Trapnell, P. D., & Meston, C. M. (2011). The relationship among sexual attitudes, sexual fantasy, and religiosity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 619–630.

Ahrold, T. K., & Meston, C. M. (2010). Ethnic differences in sexual attitudes of U.S. college students: Gender, acculturation, and religiosity factors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 190–202.

Altemeyer, B., & Hunsberger, B. (1992). Authoritarianism, religious fundamentalism, quest, and prejudice. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 2, 113–133.

Barkan, S. E. (2006). Religiosity and premarital sex in adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45, 407–417.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bassett, R. L., Smith, H. L., Newell, R. L., & Richards, A. H. (1999). Thou shalt not like sex: Taking another look at religiousness and sexual attitudes. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 18, 205–216.

Beckwith, H. D., & Morrow, J. A. (2005). Sexual attitudes of college students: The impact of religiosity and spirituality. College Student Journal, 39, 357–367.

Brotto, L. A. (2009). The Female Sexual Function Index: A methodological critique and suggestions for improvement. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 35, 161–163.

Brotto, L. A. (2010). The DSM diagnostic criteria for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 221–239.

Brotto, L. A., Basson, R., & Luria, M. (2008). A mindfulness-based group psychoeducational intervention targeting sexual arousal disorder in women. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5, 1646–1659.

Brotto, L. A., Bitzer, J., Laan, E., Leiblum, S., & Luria, M. (2010). Women’s sexual desire and arousal disorders. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7, 586–614.

Brotto, L. A., Chik, H. M., Ryder, A. G., Gorzalka, B. B., & Seal, B. N. (2005). Acculturation and sexual function in Asian women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 34, 613–626.

Cain, V. S., Johannes, C. B., Avis, N. E., Mohr, B., Schocken, M., Skurnick, J.,…& Ory, M. (2003). Sexual functioning and practices in a multi-ethnic study of midlife women: Baseline results from SWAN. Journal of Sex Research, 40, 266–276.

Cochran, J. K., & Beeghley, L. (1991). The influence of religion on attitudes toward nonmarital sexuality: A preliminary assessment of reference group theory. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30, 45–62.

Cowden, C. R., & Bradshaw, S. D. (2007). Religiosity and sexual concerns. International Journal of Sexual Health, 19, 15–24.

Curran, C. E. (1992). Sexual ethics in the Roman Catholic tradition. In R. M. Green (Ed.), Religion and sexual health (pp. 17–35). Boston: Kluver Academic Publishers.

Davidson, J. K., Moore, N. B., & Ullstrup, K. M. (2004). Religiosity and sexual responsibility: Relationships of choice. American Journal of Health Behavior, 28, 335–346.

de Visser, R. O., Smith, A. M., Richters, J., & Rissel, C. E. (2007). Associations between religiosity and sexuality in a representative sample of Australian adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36, 33–46.

DeLamater, J. (1987). A sociological perspective. In J. H. Geer & W. T. O’Donohue (Eds.), Theories of human sexuality (pp. 237–256). New York: Plenum.

Donahue, M. J. (1985). Intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness: Review and meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 400–419.

Farmer, M. A., Trapnell, P. D., & Meston, C. M. (2009). The relation between sexual behavior and religiosity subtypes: A test of the secularization hypothesis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 852–865.

Gorsuch, R. L., & Venable, G. D. (1983). Development of an “age universal” I-E scale. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 22, 181–187.

Gunderson, M. P., & McCary, J. L. (1979). Sexual guilt and religion. The Family Coordinator, 28, 353–357.

Hawton, K., Catalan, J., & Fagg, J. (1991). Low sexual desire: Sex therapy results and prognostic factors. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 29, 217–224.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408–420.

Higgins, L. T., & Sun, C. H. (2007). Gender, social background and sexual attitudes among Chinese students. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 9, 31–42.

Hirschman, C. (2004). The role of religion in the origins and adaptation of immigrant groups in the United States. International Migration Review, 38, 1206–1233.

Holder, D. W., DuRant, R. H., Harris, T. L., Daniel, J. H., Obeidallah, D., & Goodman, E. (2000). The association between adolescent spirituality and voluntary sexual activity. Journal of Adolescent Health, 26, 295–302.

Hood, R. W., Spilka, B., Hunsberger, B., & Gorsuch, R. (1996). The psychology of religion: An empirical approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Hurlbert, D. F. (1993). A comparative study using orgasm consistency training in the treatment of women reporting hypoactive sexual desire. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 19, 41–55.

Irwin, H. J. (1993). Belief in the paranormal: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 87, 1–39.

Kennedy, M. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2002). Asian and non-Asian attitudes toward rape, sexual harrassment, and sexuality. Sex Roles, 46, 227–238.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders.

Kirkpatrick, L. A., & Hood, R. W. (1990). Intrinsic-extrinsic religious orientation: The boon or bane of contemporary psychology of religion? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 29, 442–462.

Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Laumann, E. O., Nicolosi, A., Glasser, D. B., Paik, A., Gingell, C., Moreira, E., & Wang, T. (2005). Sexual problems among women and men aged 40–80y: Prevalence and correlates identified in the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. International Journal of Impotence Research, 17, 39–57.

Leiblum, S., Wiegel, M., & Brickle, F. (2003). Sexual attitudes of US and Canadian medical students: The role of ethnicity, gender, religion, and acculturation. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 18, 473–491.

Masters, W. H., & Johnson, V. E. (1970). Human sexual inadequacy. Boston: Little, Brown.

McCabe, M. P. (2001). Evaluation of a cognitive behavior therapy program for people with sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 27, 259–271.

McCree, D. H., Wingood, G. M., DiClemente, R., Davies, S., & Harrington, K. F. (2003). Religiosity and risky sexual behavior in African-American adolescent females. Journal of Adolescent Health, 33, 260–266.

Meston, C. M., & Ahrold, T. K. (2010). Ethnic, gender, and acculturation influences on sexual behaviors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 179–189.

Meston, C. M., Trapnell, P. D., & Gorzalka, B. B. (1996). Ethnic and gender differences in sexuality: Variations in sexual behavior between Asian and non-Asian university students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 25, 33–72.

Meston, C. M., Trapnell, P. D., & Gorzalka, B. B. (1998). Ethnic, gender, and length-of-residency influences on sexual knowledge and attitudes. Journal of Sex Research, 35, 176–188.

Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F., & Dolezal, C. (2007). The Female Sexual Function Index: A methodological critique and suggestions for improvement. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 33, 217–224.

Miracle, T. S., Miracle, A. W., & Baumeister, R. F. (2003). Human sexuality: Meeting your basic needs. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Mosher, D. L. (1988). Revised Mosher guilt inventory. In C. M. Davis, W. L. Yarber, & S. L. Davis (Eds.), Sexuality-related measures (pp. 152–155). Lake Mills, IA: Graphic Publishing.

Mosher, D. L., & Cross, H. J. (1971). Sex guilt and premarital sexual experiences of college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 36, 27–32.

Plaud, J. J., Gaither, G. A., & Weller, L. A. (1998). Gender differences in the sexual rating of words. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 24, 13–19.

Pluhar, E., Frongillo, E. A., Stycos, J. M., & Dempser-McClain, D. (1998). Understanding the relationship between religion and the sexual attitudes and behaviors of college students. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 23, 288–296.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, 36, 717–731.

Putnam, R. D., & Campbell, D. E. (2010). American grace: How religion divides and unites us. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Regnerus, M. (2007). Forbidden fruit: Sex & religion in the lives of American teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rosen, R., Brown, C., Heiman, J., Leiblum, S., Meston, C., Shabsigh, R., & D’Agostino, R. (2000). The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 26, 191–208.

Rowatt, W. C., & Schmitt, D. P. (2003). Associations between religious orientation and varieties of sexual experience. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42, 455–465.

Ruma, E. H., & Mosher, D. L. (1967). Relationship between moral judgment and guilt in delinquent boys. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 72, 122–127.

Runkel, G. (1998). Sexual morality of Christianity. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 24, 103–122.

Schover, L. R., & LoPiccolo, J. (1982). Treatment effectiveness for dysfunctions of sexual desire. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 8, 179–197.

Shiah, Y. J., Tam, W. C., Wu, M. H., & Chang, F. (2010). Paranormal beliefs and religiosity: Chinese version of the Revised Paranormal Belief Scale. Psychological Reports, 107, 367–382.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445.

Stark, R., & Bainbridge, W. S. (1985). The future of religion: Secularization, revival and cult formation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Trapnell, P. (2005). A brief, balanced measure of new age paranormal beliefs. Unpublished raw data, University of Winnipeg.

Trudel, G., Marchand, A., Ravart, M., Aubin, S., Turgeon, L., & Fortier, P. (2001). The effect of a cognitive-behavioural group treatment program on hypoactive sexual desire in women. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 16, 145–164.

Weiss, A., Egan, V., & Figueredo, A. J. (2004). Sensational interests as a form of intrasexual competition. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 563–573.

Welwood, J. (2000). Toward a psychology of awakening: Buddhism, psychotherapy, and the path of personal and spiritual transformation. Boston: Shambhala Publications.

Woo, J. S. T., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2009). The role of sexuality in cervical cancer screening among Chinese women. Health Psychology, 28, 598–604.

Woo, J. S. T., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2010). Sex guilt and culture-linked barriers to testicular examinations. International Journal of Sexual Health, 22, 144–154.

Woo, J. S. T., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2011a). The role of sex guilt in the relationship between culture and women’s sexual desire. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 385–394.

Woo, J. S. T., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2011b). The relationship between sex guilt and sexual desire in a community sample of Chinese and Euro-Canadian women. Journal of Sex Research. doi:10.1080/00224499.2010.551792.

Wyatt, G. E., & Dunn, K. M. (1991). Examining predictors of sex guilt in a multiethnic sample of women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 20, 471–485.

Zinnbauer, B. J., Pargament, K. I., & Scott, A. B. (1999). The emerging meanings of religiousness and spirituality: Problems and prospects. Journal of Personality, 67, 889–919.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study came from a Hampton Research Fund from the University of British Columbia awarded to L. A. Brotto. J. S. T. Woo was funded by a Predoctoral Fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and a Predoctoral Research Trainee Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Woo, J.S.T., Morshedian, N., Brotto, L.A. et al. Sex Guilt Mediates the Relationship Between Religiosity and Sexual Desire in East Asian and Euro-Canadian College-Aged Women. Arch Sex Behav 41, 1485–1495 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9918-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9918-6