Abstract

Jewish religious singles may feel guilty and ashamed due to sexual behaviors that violate religious law, such as pre-matrimony sexual relations, viewing pornography, and masturbation. This study examined the relation between sexual guilt and shame (SGS) and psychological well-being, and whether this relation was moderated by level of religiousness. It was hypothesized that SGS would be negatively related to psychological well-being and that this relation would be stronger at higher levels of religiousness compared to lower levels of religiousness. Participants were single young-adult men (N = 165, Mage = 23.3) belonging to the national-orthodox Jewish community in Israel who completed online questionnaires. SGS was positively associated with anxiety and depression and negatively associated with life satisfaction. Additionally, the relations between SGS and measures of psychological well-being were moderated by the level of religiousness. However, contrary to the hypothesized moderation effect, SGS was positively related to negative psychological consequences and negatively related to life satisfaction at a low level of religiousness, whereas at a high level of religiousness no significant relationship between SGS and the psychological outcome measures was found. These findings may indicate that there may be adaptive elements in religion that can help an individual cope with SGS, and thus to negate its detrimental effects on psychological well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Religious single men and women deal with the struggle between their sexual needs and the religious law, which forbids pre-matrimony sexual relations and other sexual behaviors (Frances, 2018). Especially for young adults, among who sexual urges are at their peak, this struggle may provoke an intrapsychic conflict between the urge and motivation to act and the inhibition that results from religious prohibitions. Eventually, when young people find themselves acting on these urges, and carrying out forbidden sexual behaviors, such as watching pornography, masturbation, and expressing physical affection, they may experience feelings of guilt and shame (De Jong & Cook, 2021; Garceau & Ronis, 2017; Jones, 2014). Previous studies have examined the relations between sexual guilt and shame (SGS) and mental well-being among different religious/ethnic populations, such as Christians (e.g., Jones, 2014) and Muslims (e.g., Ali-Faisal, 2016). However, only a few qualitative studies have addressed these relations among the Jewish population (e.g., Frances, 2018; Ribner & Rosenbaun, 2005). The Jewish religion has a unique approach to sexuality. On the one hand, there is a prohibition on sexual activity outside of marriage, and even within married life, there are laws that limit sexual relations. For example, sexual relations are prohibited from the beginning of the woman’s menstrual cycle until a complete cessation of menstrual bleeding and immersion in a ritual bath (mikvah). On the other hand, sexual relations within married life are considered to be a mitzvah (a positive religious act) and holy (Nahary & Hartman, 2020). Hence, it is important to examine how religious Jews handle sexuality during the young adulthood period of their lives when they are still single. To fill this void, the current quantitative study examined the association between SGS and psychological well-being among single young adult men in the orthodox Jewish community. In addition, since a religious individual may feel guilt and shame because of his sexual acts that contradict personal standards that he expects from himself, as well as to absolute religious standards of a divine origin (Azim et al., 2021; De Jong & Cook, 2021), he may therefore experience a significant decrease in psychological well-being (Ali-Faisal, 2016; Gordon, 2019). In contrast to a non-religious individual whose SGS is based on personal values only, the religious individual’s SGS is also based on theological values. Therefore, the potential moderating effect of the level of religiousness on the relation between SGS and well-being was also examined.

It is important to note that in the Jewish society in Israel there are various groups, ranging from secular Jews, through traditional Jews, national-religious Jews, to the ultra-Orthodox. The prevalence of the national-religious community in the Jewish population in Israel is approximately 12 percent (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2020). The present study focused on young men belonging to the national-religious sector, which is characterized by a lifestyle that combines a commitment to religious Orthodox law, along with openness and acceptance of the modern Western world as well as a desire to integrate into general society. This reality creates a built-in tension, and poses complex challenges, one of the most prominent of which is in the domain of sexuality (Ariav, 2012). Young people in the national-religious society are subject to the influence of conflicting messages regarding sexuality. On the one hand, they are educated according to the Halacha which limits all aspects of sexual behavior and sexual thoughts to the constraints of the heterosexual marital framework between wife and husband. For the unmarried religious man, the Halacha prohibits masturbation, looking at erotic materials, purposely thinking about sexual matters, and any intimate contact with women (Frances, 2018). On the other hand, they are exposed through the internet, social networks, and the media to an open and permissive secular culture that permeates and influences them (Hermann et al., 2014). This contradiction of values and cultural norms results in a tension between their desire to live according to the religious law and the desire to live in accordance with the secular Western culture and may create a conflict for young religious people (Lahav et al., 2018). In addition, the daily reality in which these young people live increases the internal tension surrounding the difficulty of maintaining the boundaries of Halacha, i.e., the limitation of sexual relations and behaviors to within a marital relationship only (Ariav, 2012). In contrast to ultra-Orthodox youth, who grow up in a society where there is almost total gender segregation, many national religious young people live in a social environment where there is no gender segregation, for example youth movements, military service, and university. These frameworks create opportunities for singles to form dyadic relationships before marriage (Hermann et al., 2014). However, young people are required to maintain the boundaries of Halacha, even within these relationships. Furthermore, in recent years, the age of marriage in the national-religious society has been steadily increasing, so that the rate of older singles today is higher than before (Finkelstein, 2017). As a result, religious singles face conflict in the sexual field for a longer period of time (Weinstock, 2021; Yifrah, 2018).

Sexual Guilt and Shame and Well-Being

Guilt and shame are distressing emotions that occur in response to individual failure to live up to certain standards, norms, or ideals (Tracy et al., 2007). According to Dempsey (2017), guilt and shame may be adaptive to a certain degree, pushing people toward achieving moral goals and behaving according to social norms. However, excessive shame and guilt are associated with anxiety and depression, and adversely affect mental well-being (Cândea & Szentagotai-Tătar, 2018; Kim et al., 2011).

Guilt and shame are considered to be two related, but distinct, self-awareness emotions (Lewis, 1971; Tangney et al., 1996). There are different ways to distinguish between the two emotions (for a review, see Cândea & Szentagotai-Tătar, 2018). One accepted way to address the difference between them is in terms of the focus of the individual’s self-evaluation (Tracy & Robins, 2004). Guilt often involves a negative self-evaluation of one’s specific action or behavior and is related to regret or remorse over an indiscretion. In contrast, shame refers to a negative evaluation of the self as a whole, and not just of a certain behavior. When shame is experienced, the self is considered as having failed to meet the expectations or standards set by the individual (Tracy & Robins, 2004). As such, an individual who feels shame experiences a desire to disappear or get away (Tangney et al., 1996). Accordingly, sexual guilt and shame (SGS) may be defined as guilt and shame that are caused by negative appraisals of one’s sexual behaviors, thoughts, and attractions (Gordon, 2018; Mosher & Cross, 1971).

Previous research has established that SGS was associated with decreased well-being. Abdolsalehi-Najafi and Beckman (2013) found that Muslim women with high sexual guilt reported significantly lower levels of life satisfaction. Sexual guilt has been found to be associated with increased anxiety among young Christian adults (Jones, 2014) and Muslims (Ali-Faisal, 2016). Gordon (2019) reported a positive association between sexual shame and depression among a sample that included 887 men, most of them of European descent. In a qualitative study conducted by Frances (2018), Jewish religious single men reported high levels of anxiety and depression following feelings of sexual guilt and shame.

Religiousness as a Moderator of the Relation Between Sexual Guilt and Shame and Well-Being

SGS reflects the internalized values and social attitudes of the individual concerning sexuality (Hackathorn & Malm, 2021; Mosher, 1966). One of the major factors that has been found to be related to sexual attitudes is religiousness (Sümer, 2015). Since almost all religions include prohibitions or limitations on sexual behavior, it is not surprising that many studies have found that higher levels of religiousness were associated with more conservative sexual attitudes (Gyimah et al., 2013; Perry, 2018; Sümer, 2015). For example, it has been found that higher levels of religiousness were associated with more negative attitudes toward sexual thoughts and fantasies among religious Jewish adolescents (Efrati, 2019). Sümer (2015) revealed that level of religiousness was a significant predictor in explaining Muslims young adults’ negative attitudes toward masturbation and pornography. Kogan and Weißmann (2020) examined the attitudes of Christian and Muslim adolescents toward sexuality and found a positive relation between the level of religiousness and negative attitudes toward premarital sex. However, an individual’s actual sexual behavior may not always align fully with one’s religious beliefs and attitudes about sexual behavior (Frances, 2018). As a result, a religious individual may feel guilt and shame because of his sexual acts that violate religious law (Azim et al., 2021; De Jong & Cook, 2021; Garceau & Ronis, 2017; Peterman et al., 2014). That is, when the religious individual fails to behave according to the personal standards that he expects from himself, as well as to absolute religious standards of a divine origin, he may therefore experience a significant decrease in psychological well-being (Cândea & Szentagotai-Tăta, 2018; Floyd et al., 2022). In contrast to a non-religious individual whose SGS is based on personal values only, the religious individual’s SGS is also based on theological values. Therefore, it is expected that religious-based SGS will be more strongly associated with psychological distress compared to personal value-based SGS.

Religiousness as a Multidimensional Construct

Most researchers agree that religion is a multi-dimensional construct that includes many aspects, such as religious beliefs, religious motivations, and religious behaviors and ceremonies (Spilka et al., 2003). While these aspects are interrelated, they seem to represent differential aspects of religiousness and may also be differentially related to other variables. Therefore, to assess the purported moderation function of religiousness, it is important to tap these various aspects of religion (Idler et al., 2003). This is particularly the case in orthopractic religions, such as Judaism, that besides religious beliefs emphasize practice and are rich in religious behaviors in comparison to orthodoxic religions, such as Christianity, that emphasize mostly religious creed (Calvert, 2019; Cohen, 2003, 2009). Therefore, since the present study is based on a sample of Jewish individuals, it focused on three different fundamental aspects of religiousness: religious cognitions (beliefs), religious behaviors, and religious motivations. These three aspects of religiousness are now discussed in more detail.

Many studies have measured religious cognitions (i.e., the belief dimension) by examining religious fundamentalism (Saroglou et al., 2020). Williamson et al. (2010) developed a measure to assess religious fundamentalism based on the concept of intratextuality, i.e., that objective truth is to be found within the boundaries of a religion’s holy text (i.e., intratextual) rather than from external sources (i.e., extratextual) such as history or science. According to Williamson et al. (2012), there are several dimensions of attitudes toward the sacred text, which includes a belief that it is divine in origin, inerrant, privileged above all other texts, authoritative, and unchanging as the embodiment of timeless truth (Williamson & Hood, 2005). This conceptualization of religious fundamentalism has been found to be valid for adherents to the Jewish religion (Hammer & Lazar, 2019).

Another aspect that plays a central role in religion is the behavioral component (Ellison & Levin, 1998). In different religions, there are many behavioral components. Some of the behavioral components are laws that people are required to obey, such as attendance at religious ceremonies and prayer (Berry et al., 2011). In addition, there are behaviors that the individual is required to refrain from performing, such as lying and stealing (Akhverdiev & Ponomarev, 2018).

In addition, when examining religiousness, it is important to probe the motivational dimension for religiousness and religious behavior. According to Allport (1963), religious orientation or motivation is portrayed as comprising two independent dimensions: religion of means (extrinsic) and religion of ends (intrinsic). In the intrinsic religious orientation, the religious practice is the end itself, whereas in the extrinsic religious orientation the religiousness is largely a means to other ends, such as social morality or individual well-being. Lazar et al. (2002) presented a multidimensional model of motivation for Jewish religious behavior: belief in a divine order, ethnic identity, social activity, family activity, and upbringing. In the present study, we focused on the belief dimension. This dimension represents an engagement in religious behavior because of the desire to do the right thing, to relate to God, to receive an eternal reward, and to achieve a feeling of uplifting, purity, and holiness.

The Present Study

In the current study, the relations between SGS and various aspects of psychological well-being among single adult men in the National Orthodox Jewish community in Israel were examined. In addition, the purported moderating effect of religiousness—religious cognition, religious behavior, and religious motivation—on the relation between SGS and well-being was tested. Based on the above literature, our first hypothesis was that SGS would be positively associated with psychological distress (anxiety and depression) and negatively associated with life satisfaction. Our second hypothesis was that religiousness would moderate the relations between SGS and psychological distress and life satisfaction, where these relations would be stronger at higher levels of religiousness compared to lower levels of religiousness.

Method

Participants

Data collection was conducted over a period of approximately 2 weeks during March 2019. Online social networks were used to recruit participants for the study. The link was posted in WhatsApp and Facebook groups intended for single young-adult men who belong to the Jewish-National-Orthodox community. Inclusion criteria were single men aged 18 to 30, who define themselves as Jewish-National-Orthodox. A total of 438 individuals entered the survey link. Of these, 82 either did not give their consent to take part in the study or did not respond to any questionnaire items. Five participants who did not fit the inclusion criteria and 186 individuals who did not complete the questionnaire were deleted from the study. The resulting final sample comprised 165 participants. All research participants were single men and identified as being national-religious. Age ranged between 18 and 30 years (M = 23.3, SD = 3.17). The vast majority of participants (95.2%) were born in Israel. In terms of education level, 51% of them reported a high-school education, 44% reported having an undergraduate degree, and 5% reported having a graduate education or higher. Most participants (92%) studied in Orthodox Jewish institutions after high school, of which 88% studied in yeshivas (i.e., traditional Jewish educational institutions that focus on the study of Jewish religious literature) and 12% studied in mechinot (i.e., religious pre-military preparatory programs).

Measures

Sexual Behaviors

For the purpose of this study, a list of sexual behaviors relevant to young single Orthodox Jews was compiled. Although previous studies have used scales that include a wide range of sexual behaviors and thoughts (e.g., Schnarrs et al., 2010), these scales included items (e.g., items about non-conventional sex) that may discourage religious participants from participating in the study. Therefore, a list of more culturally appropriate sexual behaviors for the study’s sample was compiled including masturbation, viewing pornography, sexual thoughts, dreams with sexual content, looking sexually at others, and non-penetrative sexual physical contact (e.g., hugging, kissing, petting). For each item, participants were asked to rate the frequency of their behavior or thoughts in the past 2 months on a seven-point scale (1 = “not at all” to 7 = “more than 7 times a week”). The main purpose of this list was to provide a basis for the assessment of sexual shame and guilt. The Cronbach α coefficient was 0.75. A total mean score was computed for each participant.

Sexual Guilt and Shame

Sexual guilt and shame (SGS) were measured using an adapted version of the State Shame and Guilt Scale (SSGS; Marschall et al., 1994). The SSGS is a self-report measure comprising 15 items: five items for each of the three subscales measuring feelings of shame, guilt, and pride. Only the ten items of the shame (“I want to sink into the floor and disappear”) and guilt (“I felt bad about something I did”) subscales, that are relevant to the present study, were used. After reporting the frequency of the various sexual behaviors, respondents were asked to assess how they felt after performing these behaviors on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not feeling this way at all to 5 = Feeling this way very strongly) where higher scores indicate higher sexual guilt and shame. This measure was translated into Hebrew using the standard back-translation method. Three academics, fluent in Hebrew and in English, participated in the translation procedure. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved. The previously reported internal consistency for both subscales was good (α = 0.89 for guilt, 0.82 for shame) (Tilghman-Osborne, 2007). The coefficient α for these scales in the current study was 0.90 for guilt and 0.90 for shame. Similar to previous studies (Boudewyns et al., 2013; Sanftner & Crowther, 1998), a very high correlation between the two SSGS subscales guilt and shame (r = 0.96, p < 0.001) was found. Therefore, these two sub-scales were combined into one scale (SGS).

Depression

Depression was measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The CES-D consists of 20 items (e.g., “I felt depressed; I thought my life had been a failure”). Respondents are requested to rate the frequency of occurrence of each item during the past week on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = rarely or none of the time/ less than 1 day, 4 = most of the time /5–7 days). The questionnaire has good psychometric properties, with good internal reliability in clinical (α = 0.90) and nonclinical (α = 0.85) samples (Radloff, 1977). The Hebrew translation of the CES-D (Shmotkin & Keinan, 2011) was used. The translated questionnaire showed a good internal reliability in the current study (α = 0.91).

Anxiety

Anxiety was measured using the state subscale of the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S). The STAI-S is a self‐report questionnaire including 20 items assessing the level of anxiety (e.g., “I am tense; I am worried”) over the past week (Spielberger et al., 1971). Participants rated each of the 20 items on a 4-point Likert type scale (1 = Not at all, 4 = Very much) with higher scores indicating a higher level of anxiety. The STAI has good validity and reliability (α = 0.90) (Spielberger et al., 1983). The Hebrew translation of the STAI-S (Teichman & Malinek, 1979) was used. STAI-S showed a very good internal reliability in the current study (α = 0.93).

Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction was measured by the Personal Well-being Index (PWI; Cummins et al., 2003). The PWI is an eight-item self‐report questionnaire that measures an individual’s levels of satisfaction with various factors in his life: standard of living, health, life achievements, personal relationships, personal safety, community connectedness, future security, and religiousness. Each item is scored on an 11-point Likert scale (0 = No satisfaction at all to 10 = Completely satisfied). The PWI has been validated in a wide range of cultures and has shown a good internal consistency (α = 0.90) (Lau et al., 2005; Weinberg et al., 2016). For this study, the PWI was translated into Hebrew using the standard back-translation method. The Hebrew version of PWI showed a very good internal reliability (α = 0.87).

Religious Cognition

Religious cognition was measured by the Religious Fundamentalism Scale (IFS; Williamson et al., 2010). The IFS is a self‐report questionnaire including 12 items that measures religious fundamentalism based on the concept of intratextuality. Participants rated their agreement with the statements (e.g.,” The Sacred Writing is without question the words of God; The Sacred Writing should never be doubted, even when scientific or historical evidence outright disagrees with it”) on a 5-point Likert type scale (1 = Strongly Disagree,7 = Strongly Agree). The Hebrew translation of the IFS was used (Hammer & Lazar, 2019). The questionnaire has good psychometric properties, with good internal reliability (α = 0.93) among adults from Israel who indicated their religious affiliation as Jewish. In the current study, this measure showed a good internal reliability (α = 0.88).

Religious Behavior

Religious behavior was measured by the Jewish Religious Behavior Scale (Lazar, 2016). The original Hebrew measure contains a list of 35 various religious behaviors, all relevant to young Jewish men, some of which are considered as religiously positive but not compulsory (e.g., kissing the mezuzah on the doorpost when entering or leaving a room) some of which are compulsory, but many religious individuals are not very stringent about their performance (e.g., no physical contact whatsoever with members of the opposite sex before marriage). Participants were requested to report the frequency of their observance of each religious behavior on a Likert-type response scale ranging from 1 (never/almost never) to 5 (always/ almost always). This measure showed a very good internal reliability in the current study (α = 0.96).

Religious Motivation

Religious motivation was measured using the Motivation for Religious Behavior Questionnaire-Form A (MRBQ-A) (Lazar et al., 2002). This measure is written in Hebrew and includes 58 items that assess motivation for religious behavior among the Jewish population. The MRBQ-A provides five subscales of motivation for religious behavior: belief-in-divine-order, ethnic identity, social motivation, family, and upbringing. For the present study, we used only the belief-in-divine-order subscale (e.g., “To be in contact with God”; “Out fear of transgression”), which is the most relevant to our study. Participants were asked to rate how important the motivation in the item for religious behavior is for them, on a 5-point Likert type scale (1 = not at all important, 5 = very important). This subscale showed a good internal consistency (α = 0.93) (Lazar, 2004). In the present study, this measure showed a very good internal reliability (α = 0.95).

Procedure

Data collection was conducted through Qualtrics (http://www.qualtrics.com), which is an online platform for survey data collection. The first page was an informed consent form. The research questionnaire became electronically available only for participants who confirmed their consent. Participants were informed that the study investigates sexual guilt and shame, and that their responses will remain anonymous and be used for research purposes only. No personal identifying information was collected.

Results

The frequencies of the various sexual behavior are presented in Table 1. Almost all participants (93.6%) reported that they had sexual thoughts at least once a week. Also, more than half of the participants (58.6%) reported that they masturbated at least once a week. About half of the participants (49.3%) reported that they viewed pornography at others least once a week. Finally, about a quarter of the participants reported that, at least once week, they dreamed about sex (23.6%), had sexually looked at others (23.6%), and had sexual or physical contact such as hugging and kissing (23.4%).

The means, SDs, and zero-order correlations for the study variables are presented in Table 2. The means and standard deviations of all variables were within acceptable ranges. As can be expected, positive correlations were found between the three aspects of the religiousness variables—cognitive, behavioral, and motivational (rs = 0.52 to 0.63, i.e., moderate effect size range; Cohen, 2013). Also, as can be expected, a high correlation (r = 0.81) was found between the two aspects of psychological distress variables—anxiety and depression.

As shown in Table 2, SGS was significantly associated with the three measures of psychological well-being in the expected directions: anxiety (r = 0.23, p < 0.01), depression (r = 0.23, p < 0.01) and life satisfaction (r = − 0.20, p < 0.05).

To test the predicted moderating effect of religiousness on the relation between SGS and psychological well-being, hierarchical regression analysis was performed. In order to reduce the number of variables in the analyses, the items from the three measures of religiousness were entered into exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The first factor explained 32.7% of the variance and the item loadings were used to calculate a composite measure of religiousness. In a similar manner, all items of depression and anxiety were entered into another exploratory factor analysis. The first factor explained 38.46% of the variance, and the item loadings were used to calculate a composite measure of psychological distress. Thus, two hierarchical regressions were performed where SGS was the predictor, the composite measure of religiousness was the moderator, and psychological distress and life satisfaction were the criteria.Footnote 1

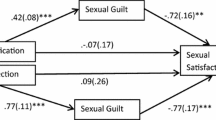

For both regressions, all predictor variables were first transformed into z scores. The measure of sexual behaviors was first entered as a control variable. On the second step, SGS and the composite religiousness score were entered. Finally, the interaction term, SGS*religiousness, was entered on the third step. Summaries of the two regressions are presented in Table 3. As can be seen from the results, for both the prediction of psychological distress and life satisfaction, the change in the R2 after entering the interaction term was statistically significant, (∆R2 psychological distress = 0.08, ∆R2 life satisfaction = 0.11; ps < 0.01) indicating that religiousness moderated the relations between SGS and psychological well-being.

In order to understand the moderating effect, simple slope analysis was used to calculate the two psychological well-being scores for − 1 SD, average, and + 1 SD on SGS and religiousness (Aiken & West, 1991). The results are presented in Figs. 1 and 2. Figure 1 shows that while SGS was positively related to psychological distress at low and average levels of religiousness, SGS was not significantly associated with psychological distress at a high level of religiousness. Figure 2 shows a similar moderation effect for the prediction of life satisfaction.

Discussion

This study addressed the struggle that Orthodox Jewish young single men may experience, while trying to maintain a balance between their sexual needs and the Jewish law, which forbids pre-matrimony sexual relations (Frances, 2018). It was assumed that among these religious young people, there would be an association between guilt and shame over sexual activities that are transgressions according to the Jewish laws (e.g., pornography, masturbation and expressing physical affection), and well-being, and that this association would be moderated by level of religiousness.

The first hypothesis, that a high level of sexual guilt and shame would be associated with a decreased level of well-being, was supported. Specifically, sexual guilt and shame were found to be related to lower levels of life satisfaction and higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms. These findings are consistent with previous studies that found these relations among young adults Christian (Jones, 2014) and Muslim (Ali-Faisal, 2016). These findings may be explained by the self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987). This theory suggested that the degree of the discrepancy between the actual and ideal self is related to a variety of psychological consequences, including guilt and shame. Specifically, it has been proposed that a discrepancy between how one experiences the self and one’s own internalized ideals is related to guilt, whereas a discrepancy between one’s sense of self and what one perceives other people hold as standards is related to shame. Accordingly, religious singles may experience gaps between these self-representations when their actual sexual behaviors do not align fully with their religious beliefs and social norms about these behaviors. This self-discrepancy is associated with guilt and shame that may lead to anxiety, depression, and decreased level of life satisfaction (Jones, 2014).

As predicted, religiousness was found to moderate the relationship between sexual guilt and shame and well-being. However, the pattern of the moderation effect was contrary to that hypothesized. It was expected that higher levels of religiousness would amplify the association between sexual guilt and lower psychological well-being. However, the results showed that at higher levels of religiousness, the association between sexual guilt and the outcome measures was weaker and not statistically significant. In contrast, at lower levels of religiousness, sexual guilt and shame were associated with lower psychological well-being.

One possible explanation for this unexpected outcome is that religion itself provides believers with tools and adaptation mechanisms that may enable them to cope with situations in which they do not meet the standards set out by that religion and that evoke guilt and shame (Dew et al., 2008). These mechanisms involve a variety of behavioral and psychosocial constructs that include provision of social resources (e.g., social ties, social support), coping resources (i.e., particular cognitive or behavioral responses to stress), promotion of positive self-perceptions (e.g., self-esteem, feelings of personal mastery), as well as generation of other positive emotions (e.g., love, forgiveness, and self-compassion) (Ellison & Levin, 1998). These adaptive coping mechanisms may help an individual with a high level of religiousness to maintain a high level of well-being, despite having sexual guilt and shame. In contrast, people with a low level of religiousness experience guilt and shame following their sexual transgressions, but their connection to religion is not deep enough for it to be useful for them in handling these negative emotions. As a result, following sexual guilt and shame, they may experience a more significant decrease in psychological well-being.

This outcome may also reflect self-compassion, which is an important adaptive coping mechanism and is a central part of many religions (Ghorbani et al., 2017). According to Neff (2003) “self-compassion” is defined as the emotion of compassion directed toward the self, and it includes a tolerant attitude toward our weaknesses and faults, accompanied by a desire to alleviate suffering. It is important to note that self-compassion is not a passive approach to one’s weaknesses or wrongs, but rather it includes the desire to improve and to change behavior in order to correct mistakes or overcome weaknesses that cause harm to others (Germer & Neff, 2013). Self-compassion helps to cope with feelings of guilt and shame (Sirois et al., 2019) and is positively associated with mental well-being (Zessin et al., 2015). Specifically in Judaism, this approach is at the heart of the Jewish religion, which gives a central place to “hazara betshuva,” i.e., the processes of repentance and remedial efforts in face of the experience of sin. This process comprises several stages: sorrow and regret for sin, abandonment of sin, confession of sin, and acceptance for the future, i.e., a commitment not to repeat the sin (Rambam Halachot Teshuvah, Chapter 2). When the process is accompanied by self-compassion rather than self-criticism, it can help religious singles better cope with feelings of guilt and shame resulting from sexual acts that are against the religious law, thus assisting in maintaining emotional equanimity.

In summary, the relations between sexual guilt and shame and psychological well-being were moderated by religiousness, where religiousness provided an apparent buffering effect. Sexual guilt and shame were associated with a decrease in mental well-being where the level of religiousness was low, whereas under higher levels of religiousness, no significant relationship was found between sexual guilt and shame and psychological outcomes. These findings may indicate that there are adaptive elements in religion that can help an individual cope with sexual guilt and shame, and thus negate its detrimental effects on psychological well-being.

There were some limitations to this study. In the present study, about half of the research participants who started answering the questionnaire did not complete it. Thus, our study’s sample may not represent the general population of national-religious young men. Substantial dropout rates are a common bias in sexuality studies (Cragun & Sumerau, 2018; Strassberg & Lowe, 1995), especially among men (Fenton et al., 2001). It has been suggested that individuals who agree to participate in studies focusing on sexual issues assumedly have more open-minded attitudes toward sexuality and more sexual experience than people who refuse to take part in such studies (Bouchard et al., 2019; Strassberg & Lowe, 1995). These considerations require caution in drawing conclusions from our findings and generalizing them to the entire population of religious-nationalist young men. In addition, the cross-sectional design of our study does not allow causal or temporal inferences. The study relied on self-report questionnaires, which are, of course, highly subjective. Since our study was conducted with a non-clinical population, the levels of anxiety, depression, guilt, and shame were relatively low and the level of life satisfaction was relatively high as is commonly found in non-clinical populations (e.g., Johnco et al., 2015). This may have influenced the research findings. Finally, although theoretically significant relationships were found between the variables, the correlations range from small to medium, so caution is required in drawing conclusions.

There are several practical implications of our findings. The findings of the study raise the importance of expanding the discourse on sexuality in the Orthodox religious society and raising awareness about dealing with sexuality among religious young people. Discussion of these issues may increase the community’s support, thus reducing feelings of guilt, shame, loneliness, and distress that these young people may be experiencing while coping with the conflict between religious laws and their sexual needs. A discussion of these issues may help religious young people find within their community and worldview the resources that will enable them to handle what appears to be one of the most complex conflicts faced by single young people who hold faith and religion as a way of life.

Data Availability

Data and survey materials will be made available upon request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

The moderation testing was also performed for all combinations of the three religiousness variables (cognition, behavior, motivation) and the three measures of psychological well-being (depression, anxiety, satisfaction with life). For all analyses, the results were similar to those reported here with minor differences. The detailed results are available from the first author on request.

References

Akhverdiev, E., & Ponomarev, A. (2018). Religion as factor in formation of law: Current trends. In SHS Web of Conferences (Vol. 50, p. 01024). EDP Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20185001024

Ali-Faisal, S. (2016). What’s sex got to do with it? The role of sexual experience in the sexual attitudes, and sexual guilt and anxiety of young Muslim adults in Canada and the United States. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 10(2), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0010.202

Allport, G. W. (1963). Behavioral science, religion, and mental health. Journal of Religion and Health, 2(3), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01533333

Azim, K. A., Happel-Parkins, A., Moses, A., & Haardoerfer, R. (2021). Exploring relationships between genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder, sex guilt, and religiosity among college women in the U.S. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 18(4), 770–782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.02.003

Berry, D. M., Bass, C. P., Forawi, W., Neuman, M., & Abdallah, N. (2011). Measuring religiosity/spirituality in diverse religious groups: A consideration of methods. Journal of Religion and Health, 50(4), 841–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-011-9457-9

Bouchard, K. N., Stewart, J. G., Boyer, S. C., Holden, R. R., & Pukall, C. F. (2019). Sexuality and personality correlates of willingness to participate in sex research. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 28(1), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2018-0028

Boudewyns, V., Turner, M. M., & Paquin, R. S. (2013). Shame-free guilt appeals: Testing the emotional and cognitive effects of shame and guilt appeals. Psychology and Marketing, 30(9), 811–825. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar

Calvert, I. (2019). Sanctifying security: Jewish approaches to religious education in Jerusalem. Religions, 10(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10010023

Cândea, D. M., & Szentagotai-Tăta, A. (2018). Shame-proneness, guilt-proneness and anxiety symptoms: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 58, 78–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.07.005

Cohen, A. B. (2003). Research: Religion, likelihood of action, and the morality of mentality. International Journal of Phytoremediation, 21(1), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327582IJPR1304_4

Cohen, A. B. (2009). Many forms of culture. American Psychologist, 64(3), 194–204. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015308

Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Cummins, R. A., Eckersley, R., Pallant, J., Van Vugt, J., & Misajon, R. (2003). Developing a national index of subjective Well-Being: The Australian Unity Wellbeing Index. Social Indicators Research, 64(2), 159–190. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024704320683

De Jong, D. C., & Cook, C. (2021). Roles of religiosity, obsessive–compulsive symptoms, scrupulosity, and shame in self-perceived pornography addiction: A preregistered study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(2), 695–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01878-6

Dempsey, H. L. (2017). A comparison of the social-adaptive perspective and functionalist perspective on guilt and shame. Behavioral Sciences, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7040083

Dew, R. E., Daniel, S. S., Armstrong, T. D., Goldston, D. B., Triplett, M. F., & Koenig, H. G. (2008). Religion/spirituality and adolescent psychiatric symptoms: A review. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 39(4), 381–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-007-0093-2

Efrati, Y. (2019). God, I can’t stop thinking about sex! the rebound effect in unsuccessful suppression of sexual thoughts among religious adolescents. Journal of Sex Research, 56(2), 146–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1461796

Ellison, C. G., & Levin, J. S. (1998). The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education and Behavior, 25(6), 700–720. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819802500603

Fenton, K. A., Johnson, A. M., McManus, S., & Erens, B. (2001). Measuring sexual behaviour: Methodological challenges in survey research. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 77(2), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.77.2.84

Finkelstein, A. (2017). Ha'nisuim ve ha'gerushin betoh hahevra hadatit leumit: Skirat netunim [Marriage and divorce in a national religious society: Data review]. Ne’emanei Torah Va’Avodah, 1–25. https://toravoda.org.il/en/

Floyd, C. G., Volk, F., Flory, D., Harden, K., Peters, C. E., & Taylor, A. (2022). Sexual shame as a unique distress outcome of morally incongruent pornography use: Modifications and methodological considerations. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 1293–1311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02104-7

Frances, K. (2018). The tightrope of desire: A qualitative study of sexual conflict in single heterosexual orthodox Jewish men. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 35(1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/pap0000151

Garceau, C., & Ronis, S. T. (2017). The interface between young adults’ religious values and their sexual experiences before age 16. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 26(2), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.262-a6

Germer, C. K., & Neff, K. D. (2013). Self-compassion in clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(8), 856–867. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22021

Ghorbani, N., Watson, P. J., Kashanaki, H., & Chen, Z. J. (2017). Diversity and complexity of religion and spirituality in iran: Relationships with self-compassion and self-forgiveness. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 27(4), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2017.1340100

Gordon, A. M. (2018). How men experience sexual shame: The development and validation of the Male Sexual Shame Scale. Journal of Men’s Studies, 26(1), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060826517728303

Gordon, A. (2019). Male sexual shame, masculinity, and mental health. New Male Studies an International Journal, 8(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.31164.92802

Gyimah, S. O., Kodzi, I., Emina, J., Cofie, N., & Ezeh, A. (2013). Religion, religiosity and premarital sexual attitudes of young people in the informal settlements of Nairobi Kenya. Journal of Biosocial Science, 45(1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932012000168

Hackathorn, J. M., & Malm, E. (2021). The experience of sex guilt: The roles of parenting, adult attachment, and sociosexuality. Sexuality and Culture, 26(1), 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09887-w

Hammer, J. H., & Lazar, A. (2019). Internal structure and criterion relationships for long and brief versions of the Intratextual Fundamentalism Scale (IFS) among Israeli Jews. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 11(4), 358–367. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000148

Hermann, T., Beery, G., Heller, E., Cohen, C., Lebel, Y., Moses, H., & Neumann, K. (2014). The National-Religious sector in Israel. The Israel Democracy Institute.

Idler, E. L., Musick, M. A., Ellison, C. G., George, L. K., Krause, N., Ory, M. G., Pargament, K. I., Powell, L. H., Underwood, L. G., & Williams, D. R. (2003). Measuring multiple dimensions of religion and spirituality for health research. Research on Aging, 25(4), 327–365.

Johnco, C., Knight, A., Tadic, D., Wuthrich, V. M., Pachana, N. A., & Oude Voshaar, R. C. (2015). Psychometric properties of the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory (GAI) and its short-form (GAI-SF) in a clinical and non-clinical sample of older adults. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(7), 1089–1097. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610214001586

Jones, A. E. (2014). Moderating effects of religious orientation on the relationship between sexual self-discrepancies and guilt and anxiety (Doctoral dissertation, Indiana State University). http://hdl.handle.net/10484/5576

Kim, S., Thibodeau, R., & Jorgensen, R. S. (2011). Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 68–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021466

Kogan, I., & Weißmann, M. (2020). Religion and sexuality: Between- and within-individual differences in attitudes to pre-marital cohabitation among adolescents in four European countries. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(17), 3630–3654. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1620416

Lahav, C., Ne’eman-Haviv, V., & Aviad-Wilchek, Y. (2018). Jewish orthodox national-religious youth at-risk: Characteristics and challenges. Social Issues in Israel, 26, 91–119. https://doi.org/10.26351/SIII/26/4

Lau, A. L. D., Cummins, R. A., & McPherson, W. (2005). An investigation into the cross-cultural equivalence of the personal wellbeing index. Social Indicators Research, 72(3), 403–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-0561-z

Lazar, A. (2004). Cultural influences on religious experience and motivation. Review of Religious Research, 46(1), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/3512253

Lazar, A. (2016). Personality, religiousness and spirituality—interrelations and structure—in a sample of religious Jewish women. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 19(4), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2016.1205572

Lazar, A., Kravetz, S., & Frederich-Kedem, P. (2002). The multidimensionality of motivation for Jewish religious behavior: Content, structure, and relationship to religious identity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41(3), 509–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5906.00134

Marschall, D., Sanftner, J., & Tangney, J. P. (1994). The State Shame and Guilt Scale. George Mason University.

Mosher, D. L., & Cross, H. J. (1971). Sex guilt and premarital sexual experiences of college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 36(1), 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0030454

Nahary, G., & Hartman, T. (2020). Orthodox Jewish women’s sexual subjectivity. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2020.1743972

Neff, K. (2003). Self-Compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward one self. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0761-8425(04)71291-7

Perry, S. L. (2018). Not practicing what you preach: Religion and incongruence between pornography beliefs and usage. Journal of Sex Research, 55(3), 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1333569

Peterman, J. S., LaBelle, D. R., & Steinberg, L. (2014). Devoutly anxious: The relationship between anxiety and religiosity in adolescence. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 6(2), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035447

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for research in the general population. Applied Neuropsychology:Adult, 1(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1002/ardp.19552881111

Ribner, D. S., & Rosenbaun, T. Y. (2005). Evaluation and treatment of unconsummated marriages among orthodox Jewish couples. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 31(4), 341–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230590950244

Sanftner, J. L., & Crowther, J. H. (1998). Variability in self-esteem, moods, shame, and guilt in women who binge. International Journal of Eating Disorders, Nternational Journal of Eating Disorders, 23(4), 391–397. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199805)23:4%3c391::aid-eat6%3e3.0.co;2-d

Saroglou, V., Clobert, M., Cohen, A. B., Johnson, K. A., Ladd, K. L., Brandt, P. Y., Murken, S., Muñoz-García, A., Adamovova, L., Blogowska, J., Çukur, C. S., Hwang, K. K., Miglietta, A., Motti-Stefanidi, F., Roussiau, N., & Valladares, J. T. (2020). Fundamentalism as dogmatic belief, moral rigorism, and strong groupness across cultures: Dimensionality, underlying components, and related interreligious prejudice. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000339

Schnarrs, P. W., Rosenberger, J. G., Satinsky, S., Brinegar, E., Stowers, J., Dodge, B., & Reece, M. (2010). Sexual compulsivity, the internet, and sexual behaviors among men in a rural area of the United States. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 24(9), 563–569. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2010.0117

Shmotkin, D., & Keinan, G. (2011). Who is prone to react to coinciding threats of terrorism and war? Exploring vulnerability through global versus differential reactivity. Community Mental Health Journal, 47(1), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-010-9354-9

Sirois, F. M., Bögels, S., & Emerson, L. M. (2019). Self-compassion improves parental well-being in response to challenging parenting events. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 153(3), 327–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2018.1523123

Spielberger, C. D., Gonzalez-Reigosa, F., Martinez-Urrutia, A., Natalicio, L. F., & Natalicio, D. S. (1971). Development of the Spanish edition of the state-trait anxiety inventory. Journal of Psychology, 5(3), 145–158.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, P. R., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1983). State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults (Form Y). Mind Garden. https://doi.org/10.1037/t06496-000

Spilka, B., Hood, R. W., Hunsberger, B., & Gorsuch, R. (2003). The psychology of religion: An empirical approach. Guilford Press.

Strassberg, D. S., & Lowe, K. (1995). Volunteer bias in sexuality research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 24(4), 369–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01541853

Sümer, Z. H. (2015). Gender, religiosity, sexual activity, sexual knowledge, and attitudes toward controversial aspects of sexuality. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(6), 2033–2044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9831-5

Tangney, J. P., Miller, R. S., Flicker, L., & Barlow, D. H. (1996). Are shame, guilt, and embarrassment distinct emotions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(6), 1256–1269. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1256

Teichman, Y., & Malinek, H. (1979). State-trait anxiety questionnaire, translation and modification to Hebrew. Tel Aviv University.

Tilghman-Osborne, C. (2007). The relation of guilt, shame, behavioral self-blame, and characterological self-blame to depression in adolescents over time. Doctoral dissertation, Vanderbilt university. http://etd.library.vanderbilt.edu/available/etd-04062007-135443/unrestricted/Osborn.Thesis.Format.pdf

Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2004). Putting the self into self–conscious emotions: A theoretical model. Psychological Inquiry, 15(2), 171–177. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1502

Tracy, J. L., Robins, R. W., & Tangney, J. P. (2007). The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research. Guilford Press.

Weinberg, M. K., Bennett, P. N., & Cummins, R. A. (2016). Validation of the personal wellbeing index for people with end stage kidney disease. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 11(4), 1227–1240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-015-9431-x

Weinstock, R. (2021). Mahapehat ha’sihah al miniyut ba’tsibur ha’dati one al tsoreh amiti ve’terem hegiya lesiyuma [The revolution in the discourse of sexuality in the religious public meets a real need and has not yet come to an end]. Makor- Rishon Newspaper. https://www.makorrishon.co.il/judaism/428067/

Williamson, W. P., & Hood, R. W. (2005). A new religious fundamentalism measure: Preliminary work based on the principle of intratextuality. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, Rochester, NY.

Williamson, W. P., Hood, R. W., Ahmada, A., Sadiq, M., & Hilld, P. C. (2010). The Intratextual Fundamentalism Scale: Cross-cultural application, validity evidence, and relationship with religious orientation and the Big 5 factor markers. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 13(7), 721–747. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670802643047

Yifrah, J. (2018). Ha’naar ha’dati ose idealizes le’haverav ve’dehumanizes leathzemo: The religious young man idealizes his friends and dehumanizes himself. Makor–Rishon Newspaper. https://www.makorrishon.co.il/judaism/67825/

Zessin, U., Dickhäuser, O., & Garbade, S. (2015). The relationship between self-compassion and well-being: A meta-analysis. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 7(3), 340–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12051

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YW designed the study, collected the data, was responsible for statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript. AL supervised the study and wrote the manuscript. ES supervised the study and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ariel University.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wacks, Y., Lazar, A. & Sommerfeld, E. The Moderating Effect of Religiousness on the Relation Between Sexual Guilt and Shame and Well-Being Among Jewish Religious Single Men. Arch Sex Behav 52, 1549–1559 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02494-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02494-2