Abstract

Purpose of Review

African Americans are over-burdened with hypertension resulting in excess morbidity and mortality. We highlight the health impact of hypertension in this population, review important observations regarding disease pathogenesis, and outline evidence-based treatment, current treatment guidelines, and management approaches.

Recent Findings

Hypertension accounts for 50% of the racial differences in mortality between Blacks and Whites in the USA. Genome-wide association studies have not clearly identified distinct genetic causes for the excess burden in this population as yet. Pathophysiology is complex likely involving interaction of genetic, biological, and social factors prevalent among African Americans. Non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic therapy is required and specific treatment guidelines for this population are varied. Combination therapy is most often necessary and single-pill formulations are most successful in achieving BP targets.

Summary

Racial health disparities related to hypertension in African Americans are a serious public health concern that warrants greater attention. Multi-disciplinary research to understand the inter-relationship between biological and social factors is needed to guide successful treatments. Comprehensive care strategies are required to successfully address and eliminate the hypertension burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The excess burden of hypertension among African Americans is a significant public health issue as it largely accounts for black-white differences in mortality rates in the USA. Despite treatment advances and current similar control rates across most racial groups, African Americans continue to experience high rates of hypertension-attributable disease. A clear understanding of mechanisms responsible for disease excess and approaches for effective management are necessary to address this important health disparity. In this review, we focus on pathogenesis, treatment guidelines, and therapeutic strategies specific to this over-burdened population. In this review, for simplicity, the term, African Americans, represents all people of African ancestry living in the USA.

Epidemiology

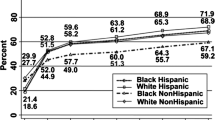

The hypertension burden among people of African descent living in America ranks higher than in other racial/ethnic groups (non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanics, and Asians) as indicated by age-adjusted prevalence estimates from the 2011–2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) [1]. Compared to other racial groups, it is well recognized that African Americans have earlier onset and greater severity of hypertension [2]. Prevalence rates are steadily increasing in practically all groups based on NHANES observations conducted from 1988 to 2012 [1, 3]. However, recent data reveal that African American women have the highest hypertension prevalence at 46.1%, compared with black men (44.9%) and non-Hispanic and Hispanic women (~ 30%) [4].

Awareness, treatment, and control rates have increased over time and are currently similar among White, Black, and Hispanic Americans [1, 5]. Soberingly, control rates for all racial groups (46–55%) fall significantly short of goals set by Million Hearts initiative (69% by 2017) [6, 7] and Healthy People 2020 (61% by 2020) (www.healthypeople.gov) [8]. Despite some treatment advances, the hypertension-attributable morbidity and mortality in African Americans remains high with 30% more nonfatal strokes, 80% more fatal strokes, 50% more CVD, and 4-fold more kidney disease [4]. In addition, the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, showed that African Americans have a 20-fold higher rate of incident heart failure before age 50 compared to White Americans, which is considered directly related to hypertension [9]. Further, black-white differences in hypertension-related hospitalization rates increased from 2004 to 2009 with 3-fold higher rates among African Americans compared to White Americans [10•]. Overall, hypertension is thought to account for 50% of the black-white mortality disparity in the USA. [11].

Pathogenesis

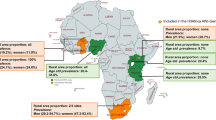

The excess burden of hypertension in African Americans is uniquely complex with likely contributions of heritable factors, thought to explain 30–50% of hypertension in the general population, along with biological, environmental, and social factors (Fig. 1). Here, we summarize recent and important findings in the expanding body of literature that seeks to understand hypertension risk in this population.

Proposed mechanism of excess hypertension burden in African Americans. The hypertension burden and its consequences are likely due to a host of inter-related biological and environmental factors superimposed on a genetically-susceptible background. Research that aims to holistically explore these mechanisms will likely be necessary to fully understand and treat this disease in this population

Update on Candidate Genes

The known heritability of BP phenotype along with the highly controversial “slavery” hypertension hypothesis has fueled the search for unique genetic susceptibility traits in this population [12]. Multiple genetic variations with intermediate phenotypes have been identified but are inconclusively linked to hypertension overburden in blacks [13]. Recently, in > 1000 African Americans in metropolitan DC, a genome-wide association study using pathway-based analysis identified two potential BP regulation candidate genes associated with systolic BP, SLC24A4 (sodium/potassium/calcium exchanger) and CACNA1H (a voltage-dependent calcium channel) with replication of some of their findings in a West African cohort [14]. This novel pathway-network approach was used to prioritize top-scoring candidates that are likely to have biological significance for BP regulation. This was the first GWAS study in African Americans focused on hypertension and similar studies in Caucasians, published simultaneously, observed potential candidates in the same genes. Unfortunately, Kidambi and co-authors could not replicate these results in an independent Milwaukee cohort of nearly 2500 African Americans [15]. A larger GWAS study including approximately 12,000 people of African descent identified two novel loci but also could not replicate results in an independent cohort [16]. The Continental Origins and Genetic Epidemiology Network (COGENT) performed the largest BP GWAS including individuals of African (29,000), European (69,000), and East Asian (19,000) ancestries and found common BP loci across ethnic groups [17]. Collectively, these inconclusive race-specific findings using state-of-the-art genetic investigational tools highlight the need for exploration of gene-environment relationships to clearly identify candidate genes contributing to the hypertension racial disparity.

Conversely, the excess burden of non-diabetic kidney disease has been largely explained by genetic variants in apolipoprotein 1 (APOL1) gene among African Americans. These renal risk variants are common in people with sub-Saharan African ancestry due to the survival advantage conferring innate immunity against trypanosomiasis and potentially other infections [18, 19]. Conflicting data exist as to whether APOL1 genetic mutations are associated with cardiovascular risk [20,21,22,23,24]. APOL1 risk alleles have recently been linked to higher systolic BP and earlier onset of hypertension in young African Americans prior to the decline in renal function [25]. However, further epidemiologic research is needed to understand whether the development of hypertension related to APOL1 risk alleles is a consequence of sub-clinical kidney injury which will later manifest as chronic kidney disease.

Therefore, although genetic susceptibility is likely to play a role, no common mutations have been convincingly identified.

Evidence for Vascular Dysfunction

Enhanced peripheral resistance contributes to the maintenance of hypertension. A review of vascular studies in normotensive black and white individuals concludes that African Americans have enhanced adrenergic vascular reactivity and attenuated vasodilator responses [26]. The vasodilatory impairment is thought to be due to both endothelium-dependent and -independent mechanisms. A growing body of literature suggests that reduced NO bioavailability contributes to endothelial dysfunction [27, 28]. Dysregulation of endothelin-1, a potent vasoconstrictor also derived from endothelial cells, may potentiate the imbalance of vasoactive hormones that leads to elevated BP and vascular remodeling [29, 30].

Newer evidence suggests that central aortic pressure better reflects the load on target organs than brachial pressure. Central pressures are more predictive of cardiovascular outcomes and may partly explain racial difference in cardiovascular outcomes despite equivalent rates of hypertension control [31,32,33,34]. For example, healthy young black men with similar brachial BPs and other clinical characteristics as young white men had higher central BPs, enhanced augmentation of central BPs, increased central arterial stiffness, increased carotid intima-media thickness, and reduced endothelial function [35]. Similar findings of greater carotid arterial stiffness were observed in blacks vs whites in a much larger cohort, participating in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study at baseline analysis [36, 37]. One study found that augmentation index, a measure of enhancement of central BP, was highest in African Americans compared to Andean-Hispanics, British Whites, and Native Americans [38]. Therefore, vascular dysfunction, which may occur prematurely and not be clinically apparent, may be important in the cause and consequences related to hypertension.

Salt-Sensitivity: Evidence for Volume Dysregulation

Salt-sensitivity is more common in normotensive and hypertensive African Americans than in the general population [39,40,41,42]. Studies suggest that obesity and low potassium diet contribute to the higher prevalence of salt-sensitivity and show this characteristic can be reversed with weight loss and greater potassium intake [43, 44]. Alterations in renal sodium handling have been implicated from several potential mechanisms: genetic polymorphisms leading to epithelial sodium channel overactivity [45,46,47], increased Na-K-2Cl co-transporter activity [48, 49], high tissue renin-angiotensin system activity [50, 51] and/or reduced responsiveness to dietary salt modifications [42], and renal neurohumoral abnormalities [52]. Nonetheless, salt sensitivity has been linked to a blunted nocturnal blood pressure dipping, proteinuria, and target organ damage in this population [53,54,55,56].

Evidence for Renin-Angiotensin System Dysregulation

Low-renin hypertension is well described in African Americans and initially interpreted as feedback inhibition to volume excess. However, predisposition to hypertension-related vascular damage suggests that RAS-mediated tissue injury occurs. One possible explanation is that suppressed circulating renin may reflect high local angiotensin II production [57]. Increased tissue angiotensin II would promotes inflammation and fibrosis and, in the kidney, lead to excess salt retention [58]. In a salt-sensitive low-renin African American population, urinary angiotensinogen, a marker of intrarenal RAS activation, was associated with BP, which supports this concept [59]. Price et al., demonstrated (1) enhanced renal plasma flow vasodilation to the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, captopril, and (2) blunted angiotensin II-mediated vasoconstriction in blacks compared to whites despite equivalent plasma renin levels [51]. Further, plasma aldosterone independently predicts blood pressure in normotensive and hypertensive African Americans [60, 61]. A recent study also showed that African Americans had enhanced aldosterone sensitivity [62]. Collectively, RAS-mediated mechanisms may play an important role in hypertension and target organ damage that is not reflected in circulating hormonal activity.

Obesity

Body mass index positively correlates with BP and is well-documented in many ethnic populations. However, the uniquely high obesity prevalence in African American women, doubling over the last two decades (www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus16.pdf#058), contributes to the hypertension disparity and challenges in management [63, 64]. Obesity impacts blood pressure through multiple mechanisms including enhanced sympathetic activation, increased salt sensitivity, activation of RAS, and glomerular hyper-filtration with subsequent renal injury [65]. Obesity-hypertension often exists within a cluster of risk factors (insulin resistance and dyslipidemia) which have additive cardiovascular risk.

Other Health Behaviors and Environmental Factors

There is data linking dietary habits and lifestyle to inadequate BP control in African Americans [66]. The modifiable risk factors contributing to hypertension, overweight, unhealthy diets including high dietary sodium intake, low potassium intake, inadequate intake of fruits and vegetables, excess alcohol intake, and lack of physical activity, are well recognized [67]. In general, African Americans are 43% less likely than White Americans to meet fruit and vegetable intake requirements [68]. Also, physical inactivity was higher among Hispanic and African American adults compared to White Americans [67]. The consumption of large amounts of alcohol > 210 g per week is associated with a higher risk of hypertension in adults but the risk is observed at low to moderate amounts (1 to 209 g) of alcohol in black men in high-stress, low socioeconomic status environments [69]. Importantly, these behavioral risk factors tend to cluster in populations. For example, African Americans born in southern versus northern states have a higher incidence of hypertension, which can partly be explained by overweight and diet [70]. However, a cross-sectional study of NHANES data from 2001 to 2006 concluded that health behaviors do not fully explain the existing racial disparities in hypertension prevalence and control and therefore, highlights the complexity of the disease pathogenesis [71].

High-stress-segregated environments (low socioeconomic status, high crime, high marital break-up, etc) have been historically linked to elevated BP levels in African Americans while similar BPs are observed across racial groups in low-stress-segregated environments [72]. These observations suggest broader environmental factors, beyond individual health behaviors, influence BP. For example, self-perceived racial discrimination among African Americans in Cardiovascular Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) participants was positively correlated with BP and contributed to black-white differences in BP in the study [73].

Racial residential segregation is a multi-dimensional construct that reflects differences in minority and white neighborhood environments beyond income gaps. CARDIA linked longitudinal BP over 25 years with change in neighborhood environment and found a small but independent and significant change in mean systolic BP (− 1.19 to − 1.33 mmHg) associated with movement from high- to medium- or low-segregation environments [74•]. Mounting data establish the impact of environment on BP and outcomes. Further characterization of these influences, their effects on pressure-control mechanisms, and incorporation into genetic studies is needed for comprehensive insight and optimal management.

Therapeutic Strategies

Lifestyle Modifications

Therapeutic lifestyle interventions such as weight management and regular exercise, salt and alcohol restriction, and tobacco cessation are integral to optimal hypertension management in all populations. In African Americans, these interventions are most effective when implemented in a culturally sensitive manner in the context of ideologies, social, and behavioral norms within the local community [75].

There is substantial evidence supporting dietary interventions in control of hypertension. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet (including the reduced-sodium modification, DASH-Na), which emphasizes high intake of fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products, significantly lowers BP in adults with pre-hypertension and hypertension [76,77,78,79,80]. These dietary approaches are as effective as single-drug pharmacologic therapy and have been observed to have even greater impact in African Americans compared to White Americans despite similar baseline BPs and clinical characteristics. Even in populations with resistant hypertension, strict salt restriction alone effectively lowers BP and cardiovascular risk [81, 82].

Multiple-modality approaches are feasible, effective, and sustainable in lowering BP in pre-hypertensive and hypertensive individuals. The Trial of Non-pharmacological Interventions in the Elderly (TONE study) demonstrated that the combination of modest weight loss and reduction in sodium intake was additive in lowering BP and reducing cardiovascular events and resulted in approximately one-third less use of antihypertensive medication [83]. Interestingly, the Adventist Health Study-2 (AHS-2) cohort of 592 black Seventh-day Adventists, designed to examine the relationship between vegetarian diets and cardiovascular disease risk, showed that vegetarian dietary patterns were linked to approximately 50% lower odds ratios of hypertension and obesity compared to non-vegetarians [84] Therefore, behavior modifications should be an integral part of the approach to management. However, successful implementation of lifestyle management strategies remains challenging. A multi-disciplinary expert panel identified a range of barriers, from patient and patient environment to healthcare practice and resources, limiting the success of interventions [75]. The group recommended further research to drive health system and public policy changes toward sustainable interventions that are likely to have substantial impact in over-burdened populations.

Pharmacotherapy

Comment on Race-Specific Approaches to Therapy

Average greater BP responses to diuretics and calcium channel blockers (along with lesser responses to RAS-blockers and β-blockers) in African Americans compared to White Americans have led some guidelines to recommend these agents as initial therapy in this population (Table 1) [85,86,87,88,89,90,91]. However, a meta-analysis of clinical trials in Black vs White men demonstrate wide variation in BP responses for both races and an overall, 80–95% overlap in BP responsiveness by drug class [92]. Further, no known biomarker, pharmacogenomic, or pharmacokinetic profile consistently predicts therapeutic responses to diuretics, calcium channel blockers, β-blockers, or ACE inhibitors in African Americans [93]. In addition, the severity of hypertension in most patients requires combination therapy which is considered equally effective across races. Importantly, all guidelines recommend that specific treatments for compelling indications drive therapeutic strategy for all populations due to evidence-based benefits. Therefore, individual therapy should be guided by a comprehensive examination including lifestyle behaviors and environment, family history, clinical characteristics, and assessment of end-organ injury along with careful follow-up.

When to Treat (Table 2)

Although the optimal BP target in the general population remains unclear, general population guidelines worldwide agree that treatment is warranted for stage 1 hypertension (BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg) [86,87,88,89,90,91, 94]. However, guidelines vary regarding BP targets in older persons in the general population. For African Americans specifically, the 2010 International Society of Hypertension in Blacks (ISHIB) consensus panel recommends more aggressive therapy than proposed by other guidelines. The ISHIB panel endorses BP targets of < 135/85 for primary prevention, < 130/80 for secondary prevention, and initiation of lifestyle modifications at BP ≥ 115/75 [85]. These guidelines focus on risk stratified treatment and early use of two-drug therapies for BPs > 15/10 mmHg above the recommended target. For the general population, the 2014 Evidence-Based US Guidelines (also known as JNC8) recommends raising the BP target in patients > 60 years without diabetes and chronic kidney disease to 150 mmHg [91]. These guidelines have been highly controversial. A dissenting group of JNC8 panel members argue that the higher BP goal would apply to high-risk populations including African Americans and potentially (1) lead to increased BPs in the treated population and (2) leave a large proportion of high-risk patient with stage 1 hypertension untreated [95••]. Other groups also oppose the BP target change for African Americans citing the higher prevalence of CVD risk factors other than hypertension in this population, the persistent disparities of hypertension-attributable morbidity and mortality and the disproportionately high prevalence of poorly controlled BP in women, particularly African American women [96].

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) challenges the consideration to relax BP targets [97]. SPRINT is the largest randomized controlled trial to evaluate the impact of intensive BP therapy (systolic BP < 120 mmHg) in a diverse population. The trial included non-diabetic adults with high cardiovascular risk where approximately one third of the population were women, African American, and over age 75 years and had chronic kidney disease. The trial was terminated after 3 years due to the 25% reduction in cardiovascular composite outcomes in the intensive BP group. These results differ from the Acton to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial which did not see a difference with intensive BP management in a smaller population with type 2 diabetes [98]. Nonetheless, these trials highlight our uncertainty of the ideal BP target and SPRINT, with beneficial outcomes and no significant harm, opens the door for more aggressive therapy in high-risk populations, including African Americans.

Treatment Outcomes in African Americans by Drug Class

Diuretics

The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT), a double-blind RCT of 42,448, including 35% African Americans, high-risk hypertensive adults, showed that chlorthalidone, a thiazide-type diuretic was superior to amlodipine, lisinopril, and doxazosin in lowering BP and preventing target-organ damage in Blacks [99]. Chlorthalidone is more potent and longer-acting than HCTZ with equivalent risks of hypokalemia at low dose [100]. Diuretics are very effective in combination with other agents and essential in treating resistant HTN and chronic kidney disease [55, 101].

Calcium Channel Blockers

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are effective and well tolerated in all populations including African Americans [102, 103]. Regarding outcomes, in ALLHAT trial, amlodipine was associated with a higher risk of heart failure in blacks and non-blacks despite equivalent outcomes in other cardiovascular events [99]. However, the International Verapamil SR and Trandolapril Study (INVEST), comparing verapamil-trandolapril to atenolol-HCTZ in patients with hypertension and heart disease, showed no difference in cardiovascular outcomes in the study population including 13% African Americans [104]. The Avoiding Cardiovascular Events through Combination Therapy in Patients Living with Hypertension (ACCOMPLISH) trial, including 12% African Americans, showed superiority of amlodipine-benezapril vs HCTZ-benezapril in preventing CV events despite similar BP [105].

Renin-Angiotensin System Inhibitors

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) are less likely recommended as initial therapy in blacks based on reduced race-specific group response rates to monotherapy [92, 106] and concerning outcomes in several hypertension clinical trials. In ALLHAT, when compared to treatment with chlorthalidone, blacks treated with lisinopril had higher blood pressures and an increased relative risk for heart failure (RR 1.3), stroke (RR 1.4), and combined cardiovascular outcomes (RR of 1.19) [99] Weir and colleagues, observed that higher doses of trandolapril in blacks were necessary to achieve equivalent BP responses observed in non-blacks which may support the pathophysiologic concept of enhanced tissue renin-angiotensin system (RAS) activation and the differences in ALLHAT clinical outcomes [107]. Also, in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension (LIFE) study, where losartan was compared to atenolol therapy, African Americans had increased risk of reaching the composite cardiovascular endpoint (hazard ratio 1.67) whereas whites experienced reduced risk (hazard ratio 0.83) [108]. However, for proteinuric kidney disease, ACEI/ARBs are first line for all populations including African Americans, due to their clear renoprotective effects [109, 110]. The African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) study, a double-blind RCT of 1094 African American patients with hypertension and chronic kidney disease, showed that antihypertensive therapy with ramipril was superior to metoprolol or amlodipine for composite renal outcomes in proteinuric patients. However, more recent analysis has demonstrated that participants homozygous for APOL1 gene mutations experience unrelenting progressive disease independent of antihypertensive therapy or BP goal [111, 112]. Additionally, patients with chronic kidney disease are a high-cardiovascular-risk population. A recent meta-analysis confirms that ACEI or ARB therapy provides cardioprotection in the kidney disease population [113]. Therefore, although guidelines steer physicians away from RAS-blocking agents as initial treatment in primary prevention, the burden of kidney disease, heart failure, and diabetes in African Americans commonly dictates their use. Notably, ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema or cough occurs more frequently among black patients and can occur at any time in treatment course so patients should be made aware of this disproportionate risk [114].

Aldosterone antagonist-based therapy is supported by the evidence of enhanced aldosterone sensitivity and increased aldosterone-regulated epithelial sodium channel activity in African Americans [45,46,47, 62]. Amiloride, spironolactone, and eplerinone are safe and effective and excellent for combination therapy and resistant hypertension management [115, 116] but should be avoided in patients with significant renal impairment [117].

β-Blockers

Initial therapy with the conventional β-blockers (BB) is no longer recommended in most guidelines unless compelling indication. However, the cardioselective 3rd generation BBs, nebivolol, and carvedilol, with additional NO-mediated vasodilating properties [118], are safe and effective in African Americans and associated with improvement in arterial stiffness and endothelial function in an obese hypertensive black population [119, 120]. In the US Carvedilol Heart Failure Trials Program including 24% African Americans, carvedilol therapy showed equivalent significant benefits in White and African American patients with heart failure [121].

Combination Therapy

The majority of hypertensive adults including African Americans require more than one medication for optimal BP control and race-based equivalent response rates to combination therapy have been noted [122]. A meta-analysis of 11,000 patients from 42 trials evaluating the effect of combining antihypertensive agents from four different classes—thiazides, BB, ACEI, and CCB compared to doubling the dose of one agent demonstrated that combination therapy was five times more effective than doubling dose irrespective of dose or pretreatment blood pressure levels [123]. Also, combination low-dose therapy is well tolerated and resulted in less overall healthcare cost than higher dose of single agents.

ISHIB recommends the use of combination therapy for African Americans with BP > 15/10 mmHg above BP targets while other guidelines recommends combination therapy for the general population at > 20/10 mmHg (Table 1) [94, 124]. Effective combinations include a diuretic or calcium channel blocker with another agent and single pill fixed-dose combinations demonstrate better adherence [124,125,126]. Notably, single-pill combination therapy is more effective in achieving BP control within 1 year when compared to monotherapy, or free combination therapy [122].

Conclusion

Hypertension in African Americans is associated with uniquely high target-organ risk and clearly needs a multi-faceted collaborative effort to successfully eliminate the well-recognized health disparities. First, a multi-disciplinary research approach, exploring genomes to exposomes, is needed to comprehensively gain insight on the uniquely high burden in African Americans and guide effective multi-targeted therapeutic strategies. Further, understanding of mechanisms driving social/environmental influences on BP will help guide population health systems and health policy with the potential for broad health and economic benefits. Second, strategies to support collaborative teams of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, advanced practitioners, and dietitians are needed to identify clinical risk factors, behaviors, and barriers to provide patient-centered non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic best practices on a continual basis for chronic management. Third, the incorporation of novel strategies, e.g., telehealth, should be considered to engage and empower patients in self-management. Regarding guidelines, the complexity and inconsistency of recommendations, even within the US consensus groups, creates inertia that may have negative consequences for management. Fourth, expert panels should incorporate consistent evidence-based guidelines applicable to African Americans, and other high-risk, high-burdened populations that are clear and implementable for widespread use among practitioners.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;2013(133):1–8.

Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29–322.

Bromfield SG, Bowling CB, Tanner RM, Peralta CA, Odden MC, Oparil S, et al. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control among US adults 80 years and older, 1988-2010. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16(4):270–6.

Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):e28–e292.

Guo F, He D, Zhang W, Walton RG. Trends in prevalence, awareness, management, and control of hypertension among United States adults, 1999 to 2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(7):599–606.

Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Million hearts: strategies to reduce the prevalence of leading cardiovascular disease risk factors—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(36):1248–51.

Frieden TR, Berwick DM. The “Million Hearts” initiative—preventing heart attacks and strokes. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):e27.

Koh HK. A 2020 vision for healthy people. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(18):1653–6.

Bibbins-Domingo K, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Gardin JM, Arynchyn A, et al. Racial differences in incident heart failure among young adults. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(12):1179–90.

• Will JC, Nwaise IA, Schieb L, Zhong Y. Geographic and racial patterns of preventable hospitalizations for hypertension: Medicare beneficiaries, 2004-2009. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(1):8–18. This study, using Medicar data from 2004–2009, demonstrates that there is a higher rate of hypertension-related hospitalizations among African Americans and that the gap between black and white people for these potentially preventable hospitalizations is increasing

Harper S, MacLehose RF, Kaufman JS. Trends in the black-white life expectancy gap among US states, 1990-2009. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(8):1375–82.

Wilson TW, Grim CE. Biohistory of slavery and blood pressure differences in blacks today. A hypothesis. Hypertension. 1991;17(1 Suppl):I122–8.

Kaplan NM. Kaplan’s clinical hypertension. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lipincott WIlliams & Williams; 2010.

Adeyemo A, Gerry N, Chen G, Herbert A, Doumatey A, Huang H, et al. A genome-wide association study of hypertension and blood pressure in African Americans. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(7):e1000564.

Kidambi S, Ghosh S, Kotchen JM, Grim CE, Krishnaswami S, Kaldunski ML, et al. Non-replication study of a genome-wide association study for hypertension and blood pressure in African Americans. BMC Med Genet. 2012;13:27.

Fox ER, Young JH, Li Y, Dreisbach AW, Keating BJ, Musani SK, et al. Association of genetic variation with systolic and diastolic blood pressure among African Americans: the Candidate Gene Association Resource study. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(11):2273–84.

Franceschini N, Fox E, Zhang Z, Edwards TL, Nalls MA, Sung YJ, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of blood-pressure traits in African-ancestry individuals reveals common associated genes in African and non-African populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93(3):545–54.

Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, Lecordier L, Uzureau P, Freedman BI, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329(5993):841–5.

Kruzel-Davila E, Wasser WG, Aviram S, Skorecki K. APOL1 nephropathy: from gene to mechanisms of kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(3):349–58.

Freedman BI, Gadegbeku CA, Bryan RN, Palmer ND, Hicks PJ, Ma L, et al. APOL1 renal-risk variants associate with reduced cerebral white matter lesion volume and increased gray matter volume. Kidney Int. 2016;90(2):440–9.

Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, Lu L, Palmer ND, Smith SC, Bagwell BM, et al. APOL1 associations with nephropathy, atherosclerosis, and all-cause mortality in African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2015;87(1):176–81.

Ito K, Bick AG, Flannick J, Friedman DJ, Genovese G, Parfenov MG, et al. Increased burden of cardiovascular disease in carriers of APOL1 genetic variants. Circ Res. 2014;114(5):845–50.

Mukamal KJ, Tremaglio J, Friedman DJ, Ix JH, Kuller LH, Tracy RP, et al. APOL1 genotype, kidney and cardiovascular disease, and death in older adults. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(2):398–403.

McLean NO, Robinson TW, Freedman BI. APOL1 gene kidney risk variants and cardiovascular disease: getting to the heart of the matter. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(2):281–9.

Nadkarni GN, Wyatt CM, Murphy B, Ross MJ. APOL1: a case in point for replacing race with genetics. Kidney Int. 2017;91(4):768–70.

Taherzadeh Z, Brewster LM, van Montfrans GA, VanBavel E. Function and structure of resistance vessels in black and white people. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12(6):431–8.

Mata-Greenwood E, Chen DB. Racial differences in nitric oxide-dependent vasorelaxation. Reprod Sci. 2008;15(1):9–25.

Vita JA. Nitric oxide and vascular reactivity in African American patients with hypertension. J Card Fail. 2003;9(5 Suppl Nitric Oxide):S199–204. discussion S5-9

Campia U, Cardillo C, Panza JA. Ethnic differences in the vasoconstrictor activity of endogenous endothelin-1 in hypertensive patients. Circulation. 2004;109(25):3191–5.

Ergul A. Hypertension in black patients: an emerging role of the endothelin system in salt-sensitive hypertension. Hypertension. 2000;36(1):62–7.

Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kizer JR, Lee, Galloway JM, Ali T, et al. Central pressure more strongly relates to vascular disease and outcome than does brachial pressure: the Strong Heart Study. Hypertension. 2007;50(1):197–203.

Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, Boutouyrie P, Giannattasio C, Hayoz D, et al. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(21):2588–605.

Safar ME, Blacher J, Pannier B, Guerin AP, Marchais SJ, Guyonvarc'h PM, et al. Central pulse pressure and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension. 2002;39(3):735–8.

Waddell TK, Dart AM, Medley TL, Cameron JD, Kingwell BA. Carotid pressure is a better predictor of coronary artery disease severity than brachial pressure. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):927–31.

Heffernan KS, Jae SY, Wilund KR, Woods JA, Fernhall B. Racial differences in central blood pressure and vascular function in young men. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295(6):H2380–7.

Din-Dzietham R, Couper D, Evans G, Arnett DK, Jones DW. Arterial stiffness is greater in African Americans than in whites: evidence from the Forsyth County, North Carolina. ARIC Cohort Am J Hypertens. 2004;17(4):304–13.

Hall JL, Duprez DA, Barac A, Rich SS. A review of genetics, arterial stiffness, and blood pressure in African Americans. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2012;5(3):302–8.

Chirinos JA, Kips JG, Roman MJ, Medina-Lezama J, Li Y, Woodiwiss AJ, et al. Ethnic differences in arterial wave reflections and normative equations for augmentation index. Hypertension. 2011;57(6):1108–16.

Luft FC, Grim CE, Higgins JT Jr, Weinberger MH. Differences in response to sodium administration in normotensive white and black subjects. J Lab Clin Med. 1977;90(3):555–62.

Madhavan S, Alderman MH. Ethnicity and the relationship of sodium intake to blood pressure. J Hypertens. 1994;12(1):97–103.

Weinberger MH. Salt sensitivity of blood pressure in humans. Hypertension. 1996;27(3 Pt 2):481–90.

He FJ, Markandu ND, Sagnella GA, MacGregor GA. Importance of the renin system in determining blood pressure fall with salt restriction in black and white hypertensives. Hypertension. 1998;32(5):820–4.

Rocchini AP, Key J, Bondie D, Chico R, Moorehead C, Katch V, et al. The effect of weight loss on the sensitivity of blood pressure to sodium in obese adolescents. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(9):580–5.

Wilson DK, Sica DA, Miller SB. Effects of potassium on blood pressure in salt-sensitive and salt-resistant black adolescents. Hypertension. 1999;34(2):181–6.

Nesbitt S, Victor RG. Pathogenesis of hypertension in African Americans. Congest Heart Fail. 2004;10(1):24–9.

Baker EH, Dong YB, Sagnella GA, Rothwell M, Onipinla AK, Markandu ND, et al. Association of hypertension with T594M mutation in beta subunit of epithelial sodium channels in black people resident in London. Lancet. 1998;351(9113):1388–92.

Ambrosius WT, Bloem LJ, Zhou L, Rebhun JF, Snyder PM, Wagner MA, et al. Genetic variants in the epithelial sodium channel in relation to aldosterone and potassium excretion and risk for hypertension. Hypertension. 1999;34(4 Pt 1):631–7.

Chun TY, Bankir L, Eckert GJ, Bichet DG, Saha C, Zaidi SA, et al. Ethnic differences in renal responses to furosemide. Hypertension. 2008;52(2):241–8.

Pratt JH, Ambrosius WT, Agarwal R, Eckert GJ, Newman S. Racial difference in the activity of the amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel. Hypertension. 2002;40(6):903–8.

Price DA, Fisher ND, Lansang MC, Stevanovic R, Williams GH, Hollenberg NK. Renal perfusion in blacks: alterations caused by insuppressibility of intrarenal renin with salt. Hypertension. 2002;40(2):186–9.

Price DA, Fisher ND, Osei SY, Lansang MC, Hollenberg NK. Renal perfusion and function in healthy African Americans. Kidney Int. 2001;59(3):1037–43.

Williams SF, Nicholas SB, Vaziri ND, Norris KC. African Americans, hypertension and the renin angiotensin system. World J Cardiol. 2014;6(9):878–89.

Bankir L, Bochud M, Maillard M, Bovet P, Gabriel A, Burnier M. Nighttime blood pressure and nocturnal dipping are associated with daytime urinary sodium excretion in African subjects. Hypertension. 2008;51(4):891–8.

Pimenta E, Gaddam KK, Pratt-Ubunama MN, Nishizaka MK, Aban I, Oparil S, et al. Relation of dietary salt and aldosterone to urinary protein excretion in subjects with resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2008;51(2):339–44.

Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S, Goff DC, Murphy TP, Toto RD, et al. Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2008;51(6):1403–19.

Sanders PW. Dietary salt intake, salt sensitivity, and cardiovascular health. Hypertension. 2009;53(3):442–5.

Price DA, Fisher ND. The renin-angiotensin system in blacks: active, passive, or what? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2003;5(3):225–30.

Boddi M, Poggesi L, Coppo M, Zarone N, Sacchi S, Tania C, et al. Human vascular renin-angiotensin system and its functional changes in relation to different sodium intakes. Hypertension. 1998;31(3):836–42.

Michel FS, Norton GR, Maseko MJ, Majane OH, Sareli P, Woodiwiss AJ. Urinary angiotensinogen excretion is associated with blood pressure independent of the circulating renin-angiotensin system in a group of African ancestry. Hypertension. 2014;64(1):149–56.

Kidambi S, Kotchen JM, Krishnaswami S, Grim CE, Kotchen TA. Aldosterone contributes to blood pressure variance and to likelihood of hypertension in normal-weight and overweight African Americans. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22(12):1303–8.

Kotchen TA, Kotchen JM, Grim CE, Krishnaswami S, Kidambi S. Aldosterone and alterations of hypertension-related vascular function in African Americans. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22(3):319–24.

Tu W, Eckert GJ, Hannon TS, Liu H, Pratt LM, Wagner MA, et al. Racial differences in sensitivity of blood pressure to aldosterone. Hypertension. 2014;63(6):1212–8.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–14.

Hall JE, Brands MW, Henegar JR. Mechanisms of hypertension and kidney disease in obesity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;892:91–107.

Landsberg L, Aronne LJ, Beilin LJ, Burke V, Igel LI, Lloyd-Jones D, et al. Obesity-related hypertension: pathogenesis, cardiovascular risk, and treatment: a position paper of The Obesity Society and the American Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2013;15(1):14–33.

Ferdinand KC, Ferdinand DP. Race-based therapy for hypertension: possible benefits and potential pitfalls. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2008;6(10):1357–66.

Writing Group M, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38–360.

Casagrande SS, Wang Y, Anderson C, Gary TL. Have Americans increased their fruit and vegetable intake? The trends between 1988 and 2002. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4):257–63.

Fuchs FD, Chambless LE, Whelton PK, Nieto FJ, Heiss G. Alcohol consumption and the incidence of hypertension: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Hypertension. 2001;37(5):1242–50.

Newby PK, Noel SE, Grant R, Judd S, Shikany JM, Ard J. Race and region are associated with nutrient intakes among black and white men in the United States. J Nutr. 2011;141(2):296–303.

Redmond N, Baer HJ, Hicks LS. Health behaviors and racial disparity in blood pressure control in the national health and nutrition examination survey. Hypertension. 2011;57(3):383–9.

Harburg E, Erfurt JC, Hauenstein LS, Chape C, Schull WJ, Schork MA. Socio-ecological stress, suppressed hostility, skin color, and Black-White male blood pressure: Detroit. Psychosom Med. 1973;35(4):276–96.

Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: the CARDIA Study of young black and white adults. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(10):1370–8.

• Kershaw KR, WR, Gordon-Larson P, Hicken MT, Golf DC, Carnethon M, et al. Association of changes in neighborhood-level racial residential segregation with changes in blood pressure among black adults The CARDIA study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):996–1002. This analysis from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) cohort examining longitudinal within-person changes in BP over 25 years desmonstrates that movement of African Americans from high to lower racial residentially segregated neighborhoods is independently associated with a significant reduction in systolic BP

Scisney-Matlock M, Bosworth HB, Giger JN, Strickland OL, Harrison RV, Coverson D, et al. Strategies for implementing and sustaining therapeutic lifestyle changes as part of hypertension management in African Americans. Postgrad Med. 2009;121(3):147–59.

Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):1117–24.

Svetkey LP, Simons-Morton D, Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Conlin PR, Ryan DH, et al. Effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure: subgroup analysis of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(3):285–93.

Moore TJ, Conlin PR, Ard J, Svetkey LP. DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet is effective treatment for stage 1 isolated systolic hypertension. Hypertension. 2001;38(2):155–8.

Obarzanek E, Proschan MA, Vollmer WM, Moore TJ, Sacks FM, Appel LJ, et al. Individual blood pressure responses to changes in salt intake: results from the DASH-Sodium trial. Hypertension. 2003;42(4):459–67.

Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Bray GA, Harsha D, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(1):3–10.

Diaz KM, Booth JN 3rd, Calhoun DA, Irvin MR, Howard G, Safford MM, et al. Healthy lifestyle factors and risk of cardiovascular events and mortality in treatment-resistant hypertension: the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study. Hypertension. 2014;64(3):465–71.

Pimenta E, Gaddam KK, Oparil S, Aban I, Husain S, Dell'Italia LJ, et al. Effects of dietary sodium reduction on blood pressure in subjects with resistant hypertension: results from a randomized trial. Hypertension. 2009;54(3):475–81.

Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA, Applegate WB, Ettinger WH Jr, Kostis JB, et al. Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons: a randomized controlled trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly (TONE). TONE Collaborative Research Group. JAMA. 1998;279(11):839–46.

Fraser G, Katuli S, Anousheh R, Knutsen S, Herring P, Fan J. Vegetarian diets and cardiovascular risk factors in black members of the Adventist Health Study-2. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(3):537–45.

Flack JM, Sica DA, Bakris G, Brown AL, Ferdinand KC, Grimm RH Jr, et al. Management of high blood pressure in Blacks: an update of the International Society on Hypertension in Blacks consensus statement. Hypertension. 2010;56(5):780–800.

Go AS, Bauman MA, Coleman King SM, Fonarow GC, Lawrence W, Williams KA, et al. An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hypertension. 2014;63(4):878–85.

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Bohm M, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013;31(7):1281–357.

Leung AA, Nerenberg K, Daskalopoulou SS, McBrien K, Zarnke KB, Dasgupta K, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2016 Canadian Hypertension Education Program Guidelines for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(5):569–88.

Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, Mann S, Lindholm LH, Kenerson JG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16(1):14–26.

McCormack T, Krause T, O'Flynn N. Management of hypertension in adults in primary care: NICE guideline. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(596):163–4.

James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507–20.

Sehgal AR. Overlap between whites and blacks in response to antihypertensive drugs. Hypertension. 2004;43(3):566–72.

Brewster LM, Seedat YK. Why do hypertensive patients of African ancestry respond better to calcium blockers and diuretics than to ACE inhibitors and beta-adrenergic blockers? A systematic review. BMC Med. 2013;11:141.

Ferdinand KC, Nasser SA. Understanding the Importance of Race/Ethnicity in the Care of the Hypertensive Patient. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2015;17(3):15.

•• Wright JT Jr, Fine LJ, Lackland DT, Ogedegbe G, Dennison Himmelfarb CR. Evidence supporting a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 150 mm Hg in patients over aged 60 years or older: the minority view. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(7):499–503. This report, in response to the publication of the 2014 Evidence-Based Guildelines of High Blood Pressure in Adults or JNC8 (#91), summarizes the viewpoint from a minority of the JNC8 panel members who are not in agreement with increasing the target BP level to 150 mmHg for those over 60 years old. The minority panel members provide evidence for maintaining the target systolic BP at 140 mmHg or lower in this age group

Krakoff LR, Gillespie RL, Ferdinand KC, Fergus IV, Akinboboye O, Williams KA, et al. 2014 hypertension recommendations from the eighth joint national committee panel members raise concerns for elderly black and female populations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(4):394–402.

Group SR, Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, Snyder JK, Sink KM, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103–16.

Group AS, Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, Goff DC Jr, Grimm RH Jr, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1575–85.

Wright JT Jr, Dunn JK, Cutler JA, Davis BR, Cushman WC, Ford CE, et al. Outcomes in hypertensive black and nonblack patients treated with chlorthalidone, amlodipine, and lisinopril. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1595–608.

Ernst ME, Carter BL, Zheng S, Grimm RH Jr. Meta-analysis of dose-response characteristics of hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone: effects on systolic blood pressure and potassium. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23(4):440–6.

Judd E, Calhoun DA. Management of hypertension in CKD: beyond the guidelines. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22(2):116–22.

Materson BJ, Reda DJ, Cushman WC, Massie BM, Freis ED, Kochar MS, et al. Single-drug therapy for hypertension in men. A comparison of six antihypertensive agents with placebo. The Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(13):914–21.

Saunders E, Weir MR, Kong BW, Hollifield J, Gray J, Vertes V, et al. A comparison of the efficacy and safety of a beta-blocker, a calcium channel blocker, and a converting enzyme inhibitor in hypertensive blacks. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(8):1707–13.

Pepine CJ, Handberg EM, Cooper-DeHoff RM, Marks RG, Kowey P, Messerli FH, et al. A calcium antagonist vs a non-calcium antagonist hypertension treatment strategy for patients with coronary artery disease. The International Verapamil-Trandolapril Study (INVEST): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(21):2805–16.

Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, Dahlof B, Pitt B, Shi V, et al. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(23):2417–28.

Brewster LM, van Montfrans GA, Kleijnen J. Systematic review: antihypertensive drug therapy in black patients. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(8):614–27.

Weir MR, Gray JM, Paster R, Saunders E. Differing mechanisms of action of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in black and white hypertensive patients. The Trandolapril Multicenter Study Group. Hypertension. 1995;26(1):124–30.

Julius S, Alderman MH, Beevers G, Dahlof B, Devereux RB, Douglas JG, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction in hypertensive black patients with left ventricular hypertrophy: the LIFE study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(6):1047–55.

Agodoa LY, Appel L, Bakris GL, Beck G, Bourgoignie J, Briggs JP, et al. Effect of ramipril vs amlodipine on renal outcomes in hypertensive nephrosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285(21):2719–28.

Remuzzi G, Perico N, Macia M, Ruggenenti P. The role of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in the progression of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005;99:S57–65.

Parsa A, Kao WH, Xie D, Astor BC, Li M, Hsu CY, et al. APOL1 risk variants, race, and progression of chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2183–96.

Tin A, Grams ME, Estrella M, Lipkowitz M, Greene TH, Kao WH, et al. Patterns of kidney function decline associated with APOL1 genotypes: results from AASK. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(8):1353–9.

Balamuthusamy S, Srinivasan L, Verma M, Adigopula S, Jalandhara N, Hathiwala S, et al. Renin angiotensin system blockade and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease and proteinuria: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2008;155(5):791–805.

Brown NJ, Ray WA, Snowden M, Griffin MR. Black Americans have an increased rate of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60(1):8–13.

Flack JM, Oparil S, Pratt JH, Roniker B, Garthwaite S, Kleiman JH, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of eplerenone and losartan in hypertensive black and white patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(7):1148–55.

Nishizaka MK, Zaman MA, Calhoun DA. Efficacy of low-dose spironolactone in subjects with resistant hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16(11 Pt 1):925–30.

Khosla N, Kalaitzidis R, Bakris GL. Predictors of hyperkalemia risk following hypertension control with aldosterone blockade. Am J Nephrol. 2009;30(5):418–24.

Hilas O, Ezzo D. Nebivolol (bystolic), a novel Beta blocker for hypertension. P T. 2009;34(4):188–92.

Merchant N, Searles CD, Pandian A, Rahman ST, Ferdinand KC, Umpierrez GE, et al. Nebivolol in high-risk, obese African Americans with stage 1 hypertension: effects on blood pressure, vascular compliance, and endothelial function. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2009;11(12):720–5.

Saunders E, Smith WB, DeSalvo KB, Sullivan WA. The efficacy and tolerability of nebivolol in hypertensive African American patients. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2007;9(11):866–75.

Yancy CW, Fowler MB, Colucci WS, Gilbert EM, Bristow MR, Cohn JN, et al. Race and the response to adrenergic blockade with carvedilol in patients with chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(18):1358–65.

Egan BM, Bandyopadhyay D, Shaftman SR, Wagner CS, Zhao Y, Yu-Isenberg KS. Initial monotherapy and combination therapy and hypertension control the first year. Hypertension. 2012;59(6):1124–31.

Wald DS, Law M, Morris JK, Bestwick JP, Wald NJ. Combination therapy versus monotherapy in reducing blood pressure: meta-analysis on 11,000 participants from 42 trials. Am J Med. 2009;122(3):290–300.

Flack JM, Nasser SA, Levy PD. Therapy of hypertension in African Americans. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2011;11(2):83–92.

Bangalore S, Shahane A, Parkar S, Messerli FH. Compliance and fixed-dose combination therapy. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2007;9(3):184–9.

Gupta AK, Arshad S, Poulter NR. Compliance, safety, and effectiveness of fixed-dose combinations of antihypertensive agents: a meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2010;55(2):399–407.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Nomsa Musemwa has no conflict of interest.

Crystal A. Gadegbeku receives funding from (1) NIH, NHLBI as an investigator in the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Study. NIDDK, as an investigator in the Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network, Michigan Kidney Translational Core Center. (2) American Society of Nephrology, as Chair of Policy and Advocacy for the American Society of Nephrology, she receives a stipend. (3) Akebia, Inc., study support as site investigator for the clinical trial focused on anemia management in chronic kidney disease.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Hypertension

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Musemwa, N., Gadegbeku, C.A. Hypertension in African Americans. Curr Cardiol Rep 19, 129 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-017-0933-z

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-017-0933-z