Abstract

Purpose

Cancer survivors’ needs around sexual concerns are often unmet. The primary objective of this systematic review was to examine the prevalence of and factors associated with patient-provider communication about sexual concerns in cancer.

Methods

Using PRISMA guidelines, we searched PubMed/MEDLINE, PsychInfo, and CINAHL databases for peer-reviewed quantitative research papers (2000–2015) in cancer samples. Search terms across three linked categories were used (sexuality, communication, and cancer). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Sexual Function Guidelines were used as a framework to categorize communication reported in each study.

Results

Twenty-nine studies from 10 countries (29 % in USA) were included. Studies assessed patients only (21), providers only (4), and both (4). Communication measures differed across studies and many lacked validity data. When reported by patients or providers, the average prevalence of discussing potential treatment effects on sexual function was 50 (60 % for men and 28 % for women) and 88 %, respectively. As reported by patients or providers, respectively, assessing patients’ sexual concerns (10 and 21 %) and offering treatments (22 and 17 %) were measured in fewer studies and were reported less frequently. Both patients and providers (28 and 32 %, respectively) reported a low prevalence of other non-specific communication. Greater prevalence of communication was associated with male patient gender and more years of provider experience.

Conclusions

Sexual issues go unaddressed for many cancer survivors, particularly women. Both patient and provider interventions are needed.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Enhancing patient-provider communication about sexual concerns through evidence-based interventions could improve patient sexual function and quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sexual concerns are among the most common, distressing, and persistent quality of life sequelae of cancer surgery and treatment [1–5]. These include physiological sexual dysfunction (e.g., erectile function and vaginal dryness), emotional or motivational issues (e.g., body image concerns and lack of libido), and interpersonal changes (e.g., relationship distress) [1, 6, 7]. Consideration of the effects of treatment on sexual function can influence individuals’ choice of cancer treatment or decrease adherence to treatment regimens that compromise sexual function [8, 9]. If left unaddressed, sexual concerns can negatively impact patient’s psychological health, relationship adjustment, and overall quality of life [10–12]. The addition of sexual function to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Survivorship Guidelines [13] and recent efforts to systematize evaluation of sexual concerns in cancer [14] show an increasing recognition of the need to address sexual concerns in cancer care.

Nevertheless, existing research suggests that sexual health represents an area of largely unmet need [15, 16] for cancer survivors, with many survivors not receiving adequate assistance or information [17–19]. As many as 90 % of cancer survivors report that their oncologist infrequently addresses sexual health concerns [20]. For providers, lack of appropriate training is one of the most significant barriers preventing them from discussing sexual concerns with their patients [16, 21–23] along with embarrassment, time pressure, unfamiliarity with treatment options, and prioritizing other physical symptoms [15, 24–26]. Relying on patients to raise sexual concerns, however, is an ineffective strategy because patients often do not ask for help, even if they report interest in receiving care [27]. Additionally, patients often believe that the provider would raise the issue if important, suggesting they may be reluctant to raise the issue because they feel that they are burdening their provider [15, 22, 28].

Whereas barriers to patient-provider communication about sexual concerns (CSC) in cancer have been described [21–23, 25, 29–31], to our knowledge, detailed data on the prevalence and quality of patient-provider communication about sexual concerns within cancer populations have not been synthesized. The few reviews that have been done have not specifically focused on cancer, did not synthesize data from quantitative studies, and did not study communication with providers across a range of roles (e.g., nurses only), limiting findings [18, 19]. A systematic review of patient-provider communication about sexual concerns in cancer survivors could inform the development of interventions by revealing the strengths and limitations in current clinical practice and by highlighting gaps in the research base. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to examine the prevalence of this communication through a review of empirical studies on this topic in cancer. A secondary objective was to characterize the specific types of communication that occurred, when present, and identify patient and provider factors that have been examined in relation to its prevalence.

Methods

Search strategy

Prior to searching, a review study protocol was drafted, circulated among authors, and used within the study team to guide procedures. We searched MEDLINE/PubMed, CINAHL, and PsychInfo for papers with the limits of English language and published since 2000, using the help of a professional science librarian. The final search included three sets of search terms in the title or abstract linked with “AND,” pertaining to (a) sexual health (i.e., sexuality, sexual behavior, sexual dysfunction, sexual function, sexual health, sexual issues sexual problems, and sexual side effects); (b) cancer (cancer, oncology, and neoplasms); and (c) communication (discuss, patient-provider communication, informed consent, conversation, communication, professional-patient relations, physician-patient relations, and nurse-patient relations).Footnote 1 The latter three communication terms were entered only as a MESH term or subject heading. A “NOT” HIV or HPV term was included in searches to reduce false hits. Supplemental searches included ancestry and cited reference searches; the last date of search was November 4, 2015.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Peer-reviewed papers in samples with cancer patients or providers providing quantitative data on the primary objective were the targeted papers. To meet this inclusion criterion, verbal communication about sexual function or concerns had to be measured directly, such as through survey, interview, observation, or chart review, and provide quantitative data on at least one of the following: (1) prevalence (i.e., proportion) of patients engaging in verbal communication with providers about sexual concerns or (2) prevalence (i.e., proportion) of providers engaging in verbal communication with patients about sexual concerns. Studies were excluded if they were published outside of the date range, did not contain original data (e.g., editorial), were not in cancer (e.g., in all patients attending a gynecology clinic), or were not in actual patients or providers (e.g., simulated patients). Finally, because the practice patterns investigated in older studies may not reflect current practice, searches were limited to studies published since 2000. Studies conducted using qualitative methods for data collection or analysis were included provided that they met the primary research objective.

Screening of articles

First, the lead author (JBR) screened all abstracts yielded by the search and additional methods, after removing duplicates. Then, a trained second reviewer screened 50 randomly selected titles/abstracts for inclusion/exclusion. An inter-rater kappa of .77, which falls in the high end of the “substantial agreement” category [32], was considered adequate to move to the next phase of screening [33]. Two screeners independently reviewed every paper at the full paper screening level to determine final eligibility (JBR; KS); a third reviewer (SL) was consulted to resolve any disagreements.

Data abstraction

In consultation with study team members, a standardized coding sheet was developed that served as a template for data abstraction of study design, communication measure characteristics, participant characteristics, and results. To increase accuracy, two independent reviewers abstracted all data and multiple phases of data entry and checking were implemented; authors were contacted when necessary. The NCCN Guidelines on Male and Female Sexual Function published in 2015 [34] were used as a general framework to categorize communication types reported in each study. The communication types described in the NCCN Guidelines pertaining to the most critical intended outcomes of communication were selected for the categorization of studies: preparing a patient for treatment-associated effects on sexual function and fertility by discussing potential effects, identifying patients with sexual concerns by assessing such concerns (i.e., asking about concerns, offering a written screener, or evaluating sexual concerns), and managing concerns by offering treatments or referrals. In addition, we report prevalence of patients’ asking about sexual concerns because this could be used to identify patients who have sexual complaints. Communication too general to be classified was labeled “non-specific” discussions.

Quality ratings

Items making up the quality rating items were selected based on relevant prior literature and prior use by members of our team in published systematic reviews of similar types of studies [35, 36]. Using a dichotomous rating scale of either meeting or not meeting each criterion, all studies were judged on whether they described (a) the setting and population from which the sample was drawn, (b) the sample inclusion/exclusion criteria, (c) characteristics of study participants at enrollment, (d) the rate of enrollment or completion of the survey (unless a chart review, in which case the study was given a score for this criterion based on whether consecutive, non-missing cases were abstracted), and (e) whether the communication measure had any supporting reliability or validity data (e.g., reference to prior literature supporting the measure and use of a standardized form for dialogue coding). One author coded all studies for quality on a standard template (JBR); eight studies (28 %) were randomly selected to be double scored independently by a separate reviewer (LP). An inter-rater reliability kappa based on whether the studies met or did not meet individual quality criteria was computed at .79, considered excellent agreement, and thus the primary set of quality ratings were used [32].

Results

Search results and overview of included studies

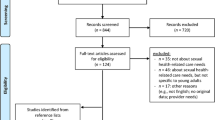

The flow of studies included is shown in Fig. 1. The search produced 1287 records, supplemented by 11 found through additional searches; 29 met inclusion criteria (27 from the initial search and 2 from the additional searches). The most common reason for exclusion was that the article did not meet the primary research objective.

An overview of the included studies is shown in Table 1. Across the included 29 studies, participants were patients (n = 21), providers (n = 4), or patients and providers (n = 4); the terms “patient-level data” and “provider-level data” are used to delineate whether the studies provide data on the proportion of either patients or providers reporting communication, respectively. Studies were conducted across 10 countries, most commonly the USA, followed by the Netherlands. The majority of studies were published since 2010. Surveys were used most often to measure communication.

As shown in Table 1, the majority of studies with either patient- or provider-level data had samples of fewer than 100 participants. Within the 10 studies in mixed cancer patient samples, breast cancer was most commonly represented, followed by gynecologic and prostate. The majority of studies with patient-level data (68 %) were characterized by ≥50 % females; 11 were conducted in female-only samples. However, in the four colorectal cancer patient studies, females made up 23–42 % of the sample; one of these studies [37] was conducted only in females. Racial or ethnic background was reported in 28 % of studies with patient-level data. Aside from the two studies conducted either in African American women [38] or in Chinese or Malaysian patients [39], the percent of Caucasian patients ranged from 80 to 100 % with an average of 90 %. This proportion is slightly higher than recent SEER data in which Caucasians make up 83 % of new cancer cases [40]. Most studies with provider-level data included more than one type of provider; nurses were included in the largest number of studies (n = 6), followed by oncologists (n = 5). All but one study, reported the gender within the provider sample [41], which was most often female. Race and ethnic background of providers were not reported.

Study quality

Overall study quality

Methodological quality ratings of included studies are summarized here (see Supplementary Table 1 for detailed quality ratings). All studies described the setting and population from which the sample was drawn, the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and at least some characteristics of study participants at enrollment, whereas just over two thirds of the studies (66 %) reported a rate of enrollment or participation [25, 38, 42–57], and 59 % offered some data supporting the validity or reliability of the measure used to assess prevalence of CSC [26, 28, 37, 38, 41, 46–51, 54–59].

Measures used to assess prevalence of CSC

The majority of included studies (62 %) used a self-report survey measure to assess prevalence of CSC [28, 37, 41–44, 46, 47, 50, 52–55, 57–61]; only one of these included a reference to a prior validation study [57]. Seven studies (24 %) assessed prevalence of CSC through patient interviews [25, 26, 38, 39, 49, 51, 62]. Two studies used chart review to assess whether CSC was documented, one by itself [63], and one alongside patient interview data [41]. Three studies (10 %) employed observation or coding of actual clinic dialogue to assess prevalence of patient-provider communication of sexual concerns [45, 48, 56], one of which [48] employed a validated tool for coding patient-provider dialogue [64]. The other two studies used observation or recordings of patient-provider dialogue combined with ethnographic or descriptive approaches to characterize communication [45, 56].

Communication types reported with prevalence rates

Nineteen studies measuring at least one NCCN type of communication are summarized in Table 2. Nearly half of the included studies (n = 14 studies; 48 %) reported a prevalence for communication that was non-specific and could not be classified. The studies that reported only on non-specific communication are discussed below but are not shown in Table 2. The most common specific communication type for which prevalence was reported was “discussing potential treatment effects on sexual function,” reported in 11 studies (38 %), followed by “discussing potential treatment effects on fertility” (n = 6 studies; 21 %), and “assessing sexual concerns” (n = 5 studies; 17 %).

Prevalence of CSC

Discussing Potential Treatment Effects on Sexual Function

Table 3 shows the prevalence of CSC with a description of the measures and results of each included study for those with patient-level data and provider-level data, respectively. An average prevalence of 50 % was reported for discussing potential treatment effects on sexual function, across 11 studies with patient-level dataFootnote 2; such discussions were more than twice as common in male patients (64 %) [28, 42, 46, 48, 63] compared to female patients (28 %) [28, 37, 46, 48, 50, 52, 63]. By comparison, the prevalence of discussions of potential treatment effects on fertility was 35 %, and such discussions occurred for 65 % of women with breast or other cancers [38, 52] compared to 9 % of men with prostate cancer [42].

The average prevalence for discussing potential treatment effects on sexual function was 88 % across three studies with provider-level data on this type of communication [41, 48, 59]. Discussing potential treatment effects on fertility was reported in only two studies with provider-level data [25, 44]; in a Moroccan study of mostly medical and radiation oncologists, the prevalence was 80 %, whereas a study of mostly nurses in the U.K. reported a prevalence of only 7 %.

Assessing sexual concerns

As shown in Table 3, the one study with patient-level data, conducted in a sample of patients with advanced cancers, reported a low prevalence of having sexual concerns assessed (10 %) [49]. With respect to patients asking their provider about sexual concerns, the average prevalence across three studies with patient-level data was 14 % [28, 49, 53].

In the five studies with provider-level data on assessing patients’ sexual concerns [25, 26, 59, 61], the average prevalence was 21 %; however, the prevalence differed by patient gender. Specifically, in a study of oncology nurses [59], the prevalence of asking male patients about erectile dysfunction was higher (52 %) compared to the prevalence of asking female patients about vaginal dryness (29%).

Addressing patients’ sexual concerns

Across three studies with patient-level data on providers addressing patients’ sexual concerns, the average prevalence was 22 %, and this was similar for male patients (23 %) [45, 51] and female patients (18 %) [51, 56]. One of these studies also reported the prevalence of referrals to a specialty clinical service (e.g., radiotherapy nursing service for dilator instruction, gynecology nurse specialist, and a women’s specialty general practice) as 12 % [56].

The only study with provider-level data on this type of communication, conducted in a mixed sample of oncology providers, reported a fairly low prevalence of offering treatment (e.g., advice on sexual positions and non-coital sex) for patients’ sexual problems (17 %) [26].

Non-specific discussions

Across 14 patient-level studies, the prevalence of non-specific communication was 28 %. The average prevalence of non-specific communication for male patients (61 %) [45, 58] was twice that reported for female patients (30 %) [25, 38, 39, 55, 56, 58, 60, 62].

Across the two studies with provider-level data on non-specific communication, the average prevalence was 42 % [25, 61].

Factors related to prevalence of CSC

Patient factors

As shown in Table 4, the most commonly examined patient factors in relation to prevalence of CSC were age, gender, and sexual function. Overall, male gender was consistently associated with increased prevalence of CSC, whereas associations between younger patient age and prevalence of CSC were less consistent. Patient sexual function was associated with CSC in two studies, although the direction of the association depended on whether the communication studied was patient-initiated or provider-initiated and how sexual function was operationalized. Specifically, worse patient sexual function was associated both with asking a provider about sexual concerns in a large mixed cancer sample [28] and with not having had a provider-initiated discussion about sexual concerns in a sample of women with vaginal or cervical cancer diagnoses [50]. Also in the latter study, having fewer sexual morbidities was significantly associated with provider-initiated communication about sexual changes [50]. Several factors—each examined in only one study—were significantly associated with a greater prevalence of CSC (e.g., stage of disease, provider age, and departmental policy), whereas other factors were not significant (e.g., relationship status, patient education, and type of treatment).

Provider factors

The most commonly studied provider factors were years of experience, gender, age, and clinic setting. A greater number of years’ experience were significantly associated with greater prevalence of CSC in two out of three studies; older age—which may be confounded with years’ experience—was also associated with greater prevalence of discussion in one study of oncology nurses [59]. Results were inconsistent with regard to provider gender. Several provider factors were examined in one particular study [59] and found to be significantly related to greater prevalence of CSC (e.g., older patient age and presence of a departmental policy to raise sexual concerns).

Discussion

Sexual sequelae of cancer treatment are significantly under-addressed yet are relevant to cancer survivors of both genders and across a range of ages and for those with both early and advanced stage disease [2, 65, 66]. Findings from this review demonstrate substantial room for improvement in communication about sexual concerns. The most common type of communication observed in the studies included in this review—and the most prevalent type of communication, occurring in half of patients—was discussing potential effects of cancer treatment on sexual function. By contrast, few studies assessed how often providers asked patients about sexual concerns and such assessment occurred less often, suggesting that the barriers to discussions of sexual concerns [15, 22, 67, 68], may increase through the treatment trajectory. As an example, compared to providing information about potential sexual side effects of treatment, which could fit easily into an informed consent discussion, identifying and treating sexual concerns further down the road may require a greater degree of training (e.g., knowledge and competence) and sensitivity to accomplish effectively, making these skills a particularly fruitful target for intervention. From a patient perspective, immediately after a cancer diagnosis, sexuality may take on a lower priority compared to the objective of completing active treatment [69]. Following active treatment, however, survivors may gain interest in maintaining or improving their quality of life, and for many, this includes increased value on sexual function and activity. Therefore, the lack of assessment and management are of concern to the growing number of long-term cancer survivors, many of whom will face persistent sexual concerns as a result of their cancer treatments.

Patient gender emerged as an important factor associated with prevalence of CSC, with discussions of potential sexual side effects and non-specific discussions occurring in at least twice as many male patients as female patients. Moreover, both studies statistically examining patient gender as a factor related to CSC found significant effects favoring male patients. Several factors may contribute to the gender discrepancy, including greater assertiveness or rates of sexual problems in male survivors [70], differences in providers’ communication behaviors [59], a greater publicity given to medical treatments for men’s sexual dysfunction, or a lack of clarity surrounding medical treatments for women’s sexual dysfunction post-cancer (e.g., topical estrogen therapy for breast cancer survivors) [71]. Thus, an even greater degree of support may be needed to promote clinical discussions of sexual concerns with women following a cancer diagnosis. Patient-focused interventions have sought to activate patients to discuss sensitive issues such as pain with their providers [72]; assuming that providers are equipped to field patients’ sexual concerns, this model could be applied to women coping with cancer-related sexual concerns to help them prioritize their concerns and to teach basic communication skills. Interestingly, in a smaller number of studies conducted in samples characterized by differing cancer diagnoses (i.e., breast, prostate, and mixed female) and age ranges, a discrepancy in the reverse direction—though not examined statistically—seemed to favor women for discussions of potential treatment effects on fertility. Sexual and fertility-related effects and concerns affect both genders and should be standard for both male and female survivors.

Findings also pointed to patient sexual function and provider experience or training as potentially important factors associated with prevalence of CSC. That worse sexual function was associated with greater prevalence of patients’ asking about sexual concerns [28] suggests that having sexual concerns may motivate patients to ask providers about such concerns. Interestingly, worse sexual function was associated with lower prevalence of discussions, when operationalized as provider-initiated in a different study [50], and fewer sexual morbidities were related to greater prevalence of provider-initiated discussions of sexual concerns in the same study [50]. These findings speak to the importance of denoting whether communication is defined as patient- or provider-initiated in interpreting associations with prevalence of CSC. Moreover, the authors of the latter study interpret their findings as suggesting that patients may differentially recall discussions with providers depending on the extent of sexual concerns they experience [50]. It is also possible that discussions about sexual concerns actually reduce patients’ sexual problems and improve patients’ sexual function; however, this will need to be evaluated in longitudinal and intervention studies. With respect to provider factors, the strongest support was found for the association between a greater number of years of experience and increased prevalence of CSC. By contrast, provider gender, age, or type (i.e., nurse vs. oncologist) were inconsistently associated with the prevalence of discussion. These findings suggest that focusing on the modifiable outcome of training could offer an encouraging direction for intervention, particularly for medical students and trainees, who lack clinical experience from which to draw. In fact, findings from several intervention studies testing either the provision of clinical symptom summaries to providers [73] or communication skills training interventions [74, 75] suggest that such approaches may offer promise in improving communication about sexual and/or fertility-related concerns.

Unexpectedly, almost half of studies collected data on the prevalence of communication that was non-specific and thus could not be categorized according to the framework used. Validated tools exist that assess patient-provider communication outside the domain of sexual health, including both observer rating tools and self-report measures [76]. Yet a substantial proportion of the included studies offered no data supporting the validity or reliability of the method used to assess prevalence of CSC, and only two studies used tools that had published validity data [48, 57]. Interestingly, data from studies with provider-level data purported discussions to be more common compared to those with patient-level data. While this discrepancy could reflect actual differences in perception or behavior, it could also reflect different methods used to assess the prevalence of CSC across the patient and provider studies. Use of standardized validated measures across studies could help explain such differences and facilitate comparisons across trials in order to determine the most efficacious interventions.

One limitation of this review was that it centered primarily on the question of how prevalent CSC is in the context of cancer, at the exclusion of other potentially important issues, such as attitudes, barriers, and degree of sexual health needs. However, these have been well described previously [15, 29, 30, 67, 68]. Also, because fertility itself was not a search term, studies focusing on fertility were likely missed and should be studied in separate fertility-specific reviews. Furthermore, future reviews that focus on providers in a particular role or within a particular cancer diagnosis could offer information on communication strengths and limitations to guide intervention development within important subgroups.

Implications for clinical practice

Although interventions hold substantial promise in improving patient-provider CSC for cancer survivors, they may not address the time pressures acutely felt by many clinicians that limit discussion of QOL concerns broadly, including sexual health. Recently, researchers have attempted to address this barrier by offering practical guidance to and promoting awareness among cancer providers, particularly on how to address sexual concerns in female cancer patients, for whom communication is especially uncommon [14, 77]. However, such guidance should complement, rather than take the place of, communication interventions targeting knowledge and skills. Multidisciplinary sexual health programs are well suited to serve as “one-stop shopping” for the assessment and treatment of cancer survivors facing sexual concerns—as recommended in the NCCN Guidelines—but these programs are not often available outside of academic cancer centers. In the absence of such programs, resources could be set aside to train a specific member of the clinical team, such as a nurse practitioner, who could serve as the point person to coordinate care around sexual concerns [78]. Supplementing these efforts could be the development of low-cost patient educational resources that could reach a large number of cancer survivors and may meet the needs of many cancer survivors; such educational handouts should be evaluated for the extent to which they adequately address survivors’ needs. Ultimately, adequate time and resources are needed to support these efforts and ensure the inclusion of sexual health into the care of cancer survivors.

Conclusion

This review fills a gap in literature on patient-provider communication about sexual concerns by quantifying the prevalence of and factors associated with such communication. Findings from this systematic review suggest that discussions of sexual concerns continue to be uncommon for cancer survivors, particularly women. Addressing sexual concerns is important—and may serve different functions—across the treatment trajectory. Findings from this review suggest greater efforts are particularly needed in increasing the assessment and management of treatment-related sexual concerns. Improving such discussions can lead to timely identification of patients with concerns and facilitate the provision of necessary treatments, thereby reducing the likelihood of long-term, worsening sexual dysfunctions and related impact on relationships and quality of life. Given these challenges, both provider-focused and patient-focused interventions may be required to increase effective communication about sexual concerns in cancer.

Notes

The term “discuss” was entered as a Boolean phrase as “discuss*” which searched for any word beginning with this item stem. The terms “sexual behavior,” “sexuality,” “communication,” and “neoplasms” were also included in relevant searches as a MESH term and/or subject heading in addition to their appearance in the title or abstract.

The Scheer study presented a prevalence rate using patient chart review (100 %) and patient self-report survey (53 %), both of which were included in the mean prevalence calculation.

References

Bober SL, Sanchez VV. Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: challenges and intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3712–9.

Burwell SR, Case LD, Kaelin C, Avis NE. Sexual problems in younger women after breast cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2815–21.

Sadovsky R, Basson R, Krychman M, Morales AM, Schover L, Wang R, et al. Cancer and sexual problems. J Sex Med. 2010;7:349–73.

Syrjala KL, Roth-Roemer SL, Abrams JR, Scanlan JM, Chapko MK, Visser S, et al. Prevalence and predictors of sexual dysfunction in long-term survivors of marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3148–57.

Taylor KL, Luta G, Miller AB, Church TR, Kelly SP, Muenz LR, et al. Long-term disease-specific functioning among prostate cancer survivors and noncancer controls in the prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian cancer screening trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2768–75.

Carmack Taylor CL, Basen-Engquist K, Shinn EH, Bodurka DC. Predictors of sexual functioning in ovarian cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:881–9.

Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Belin TR, Meyerowitz BE, Rowland JH. Predictors of sexual health in women after a breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2371–80.

Kirk MC, Hudis CA. Insight into barriers against optimal adherence to oral hormonal therapy in women with breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2008;8:155–61.

Mortimer JE. Managing the toxicities of the aromatase inhibitors. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;22:56–60.

Bacon CG, Giovannucci E, Testa M, Glass TA, Kawachi I. The association of treatment-related symptoms with quality-of-life outcomes for localized prostate carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2002;94:862–71.

Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP, Roth AJ. The association between erectile dysfunction and depressive symptoms in men treated for prostate cancer. J Sex Med. 2011;8:560–6.

Reese JB, Shelby RA, Keefe FJ, Porter LS, Abernethy AP. Sexual concerns in cancer patients: a comparison of GI and breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1179–89.

Ligibel JA, Denlinger CS. New NCCN guidelines® for survivorship care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:640–4.

Lindau ST, Abramsohn EM, Baron SR, Florendo J, Haefner HK, Jhingran A, et al. Physical examination of the female cancer patient with sexual concerns: what oncologists and patients should expect from consultation with a specialist. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:241–63.

Park ER, Norris RL, Bober SL. Sexual health communication during cancer care barriers and recommendations. Cancer J. 2009;15:74–7.

Hautamaki K, Miettinen M, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Aalto P, Lehto J. Opening communication with cancer patients about sexuality-related issues. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30:399–404.

Rasmusson EM, Plantin L, Elmerstig E. Did they think I would understand all that on my own? A questionnaire study about sexuality with Swedish cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2013;22:361–9.

East L, Hutchinson M. Moving beyond the therapeutic relationship: a selective review of intimacy in the sexual health encounter in nursing practice. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:3568–76.

Dyer K, das Nair R. Why don’t healthcare professionals talk about sex? A systematic review of recent qualitative studies conducted in the United Kingdom. J Sex Med. 2013;10:2658–70.

Sporn NJ, Smith KB, Pirl WF, Lennes IT, Hyland KA, Park ER. Sexual health communication between cancer survivors and providers: how frequently does it occur and which providers are preferred? Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24:1167–73.

Lindau ST, Surawska H, Paice J, Baron SR. Communication about sexuality and intimacy in couples affected by lung cancer and their clinical-care providers. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20:179–85.

Hordern AJ, Street AF. Communicating about patient sexuality and intimacy after cancer: mismatched expectations and unmet needs. Med J Aust. 2007;186:224–7.

Hordern AJ, Street AF. Let’s talk about sex: risky business for cancer and palliative care clinicians. Contemp Nurse. 2007;27:49–60.

Penson RT, Gallagher J, Gioiella ME, Wallace M, Borden K, Duska LA, et al. Sexuality and cancer: conversation comfort zone. Oncologist. 2000;5:336–44.

Stead ML, Brown JM, Fallowfield L, Selby P. Lack of communication between healthcare professionals and women with ovarian cancer about sexual issues. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:666–71.

Vermeer WM, Bakker RM, Stiggelbout AM, Creutzberg CL, Kenter GG, ter Kuile MM. Psychosexual support for gynecological cancer survivors: professionals’ current practices and need for assistance. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:831–9.

Hill EK, Sandbo S, Abramsohn E, Makelarski J, Wroblewski K, Wenrich ER, et al. Assessing gynecologic and breast cancer survivors’ sexual health care needs. Cancer. 2011;117:2643–51.

Flynn KE, Reese JB, Jeffery DD, Abernethy AP, Lin L, Shelby RA, et al. Patient experiences with communication about sex during and after treatment for cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2012;21:594–601.

Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E, Wong WK, Mason C, Hobbs K, et al. Talking about sex after cancer: a discourse analytic study of health care professional accounts of sexual communication with patients. Psychol Health. 2013;28:1370–90.

Traa MJ, De Vries J, Roukema JA, Rutten HJ, Den Oudsten BL. The sexual health care needs after colorectal cancer: the view of patients, partners, and health care professionals. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:763–72.

McClelland SI, Holland KJ, Griggs JJ. Vaginal dryness and beyond: the sexual health needs of women diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. J Sex Res. 2015;52:604–16.

Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37:360–3.

Regan TW, Lambert SD, Kelly B, Falconier M, Kissane D, Levesque JV. Couples coping with cancer: exploration of theoretical frameworks from dyadic studies. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1605–17.

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Survivorship. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc.; 2015.

Haywood Jr C, Beach MC, Lanzkron S, Strouse JJ, Wilson R, Park H, et al. A systematic review of barriers and interventions to improve appropriate use of therapies for sickle cell disease. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:1022–33.

Segal JB, Strouse JJ, Beach MC, Haywood C, Witkop C, Park HS et al. Hydroxyurea for the Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 165. Rockville, MD: Prepared by Johns Hopkins University Evidence-based Practice Center under contract No. 290-02-0018; February 2008.

Hendren SK, Swallow CJ, Smith A, Lipa JE, Cohen Z, MacRae HM, et al. Complications and sexual function after vaginectomy for anorectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:810–6.

Lewis PE, Sheng M, Rhodes MM, Jackson KE, Schover LR. Psychosocial concerns of young African American breast cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30:168–84.

Khoo SB. Impact of cancer on psychosexuality: cultural perspectives of Asian women. Int J Nurs Pract. 2009;15:481–8.

Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Altekruse SF et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2013, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/, based on November 2015 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2016.

Scheer AS, O’Connor AM, Chan BP, Moloo H, Poulin EC, Mamazza J, et al. The myth of informed consent in rectal cancer surgery: what do patients retain? Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:970–5.

Boyd BG, McCallum SW, Lewis RW, Terris MK. Assessment of patient concern and adequacy of informed consent regarding infertility resulting from prostate cancer treatment. Urology. 2006;68:840–4.

Cox A, Jenkins V, Catt S, Langridge C, Fallowfield L. Information needs and experiences: an audit of UK cancer patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2006;10:263–72.

Errihani H, Elghissassi I, Mellas N, Belbaraka R, Messmoudi M, Kaikani W. Impact of cancer on sexuality: how is the Moroccan patient affected? Sexologies: Eur J Sexology Sex Health / Rev Eur Sex Sante Sex. 2010;19:92–8.

Forbat L, White I, Marshall-Lucette S, Kelly D. Discussing the sexual consequences of treatment in radiotherapy and urology consultations with couples affected by prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2012;109:98–103.

Hendren SK, O’Connor BI, Liu M, Asano T, Cohen Z, Swallow CJ, et al. Prevalence of male and female sexual dysfunction is high following surgery for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;242:212–23.

Huang LL, Pu J, Liu LH, Du XB, Wang J, Li JY, et al. Cancer department nurses’ attitudes and practices in response to the sexual issues of pelvic radiation patients: a survey in Sichuan. China Contemp Nurse. 2013;43:146–51.

Kunneman M, Marijnen CA, Rozema T, Ceha HM, Grootenboers DA, Neelis KJ, et al. Decision consultations on preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer: large variation in benefits and harms that are addressed. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:39–43.

Lemieux L, Kaiser S, Pereira J, Meadows LM. Sexuality in palliative care: patient perspectives. Palliat Med. 2004;18:630–7.

Lindau ST, Gavrilova N, Anderson D. Sexual morbidity in very long term survivors of vaginal and cervical cancer: a comparison to national norms. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106:413–8.

Mohamed NE, Chaoprang Herrera P, Hudson S, Revenson TA, Lee CT, Quale DZ, et al. Muscle invasive bladder cancer: examining survivor burden and unmet needs. J Urol. 2014;191:48–53.

Scanlon M, Blaes A, Geller M, Majhail NS, Lindgren B, Haddad T. Patient satisfaction with physician discussions of treatment impact on fertility, menopause and sexual health among pre-menopausal women with cancer. J Cancer. 2012;3:217–25.

Southard NZ, Keller J. The importance of assessing sexuality: a patient perspective. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13:213–7.

Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E. Information needs associated with changes to sexual well-being after breast cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:327–37.

Vermeer WM, Bakker RM, Kenter GG, de Kroon CD, Stiggelbout AM, ter Kuile MM. Sexual issues among cervical cancer survivors: how can we help women seek help? Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24:458–64.

White ID, Allan H, Faithfull S. Assessment of treatment-induced female sexual morbidity in oncology: is this a part of routine medical follow-up after radical pelvic radiotherapy? Br J Cancer. 2011;105:903–10.

Hilarius DL, Kloeg PH, Gundy CM, Aaronson NK. Use of health-related quality-of-life assessments in daily clinical oncology nursing practice: a community hospital-based intervention study. Cancer. 2008;113:628–37.

Gilbert E, Perz J, Ussher JM. Talking about sex with health professionals: the experience of people with cancer and their partners. Eur J Cancer Care. 2016;25:280–93.

Krouwel EM, Nicolai MP, van Steijn-van Tol AQ, Putter H, Osanto S, Pelger RC, et al. Addressing changed sexual functioning in cancer patients: a cross-sectional survey among Dutch oncology nurses. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19:707–15.

Kedde H, van de Wiel HB, Weijmar Schultz WC, Wijsen C. Sexual dysfunction in young women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:271–80.

Oskay U, Can G, Basgol S. Discussing sexuality with cancer patients: oncology nurses attitudes and views. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:7321–6.

Silva Lara LA, de Andrade JM, Consolo FD, Salata Romao APM. Women’s poorer satisfaction with their sex lives following gynecologic cancer treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16:273–7.

Chorost MI, Weber TK, Lee RJ, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Petrelli NJ. Sexual dysfunction, informed consent and multimodality therapy for rectal cancer. Am J Surg. 2000;179:271–4.

Shepherd HL, Barratt A, Trevena LJ, McGeechan K, Carey K, Epstein RM, et al. Three questions that patients can ask to improve the quality of information physicians give about treatment options: a cross-over trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84:379–85.

Mercadante S, Vitrano V, Catania V. Sexual issues in early and late stage cancer: a review. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:659–65.

Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E. Perceived causes and consequences of sexual changes after cancer for women and men: a mixed method study. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:268.

Ferreira SM, Gozzo Tde O, Panobianco MS, Santos MA, Almeida AM. Barriers for the inclusion of sexuality in nursing care for women with gynecological and breast cancer: perspective of professionals. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2015;23:82–9.

Julien JO, Thom B, Kline NE. Identification of barriers to sexual health assessment in oncology nursing practice. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37:E186–90.

Reese JB, Haythornthwaite JA. Importance of sexuality in colorectal cancer: predictors, changes, and response to an intimacy enhancement intervention. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:4309–17.

Arora NK, Jensen RE, Sulayman N, Hamilton AS, Potosky AL. Patient-physician communication about health-related quality-of-life problems: are non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors willing to talk? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3964–70.

Melisko ME, Goldman M, Rugo HS. Amelioration of sexual adverse effects in the early breast cancer patient. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:247–55.

Bennett MI, Bagnall A-M, Closs SJ. How effective are patient-based educational interventions in the management of cancer pain? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2009;143:192–9.

Berry DL, Blumenstein BA, Halpenny B, Wolpin S, Fann JR, Austin-Seymour M, et al. Enhancing patient-provider communication with the electronic self-report assessment for cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1029–35.

Hordern A, Grainger M, Hegarty S, Jefford M, White V, Sutherland G. Discussing sexuality in the clinical setting: the impact of a brief training program for oncology health professionals to enhance communication about sexuality. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2009;5:270–7.

Vadaparampil ST, Gwede CK, Meade C, Kelvin J, Reich RR, Reinecke J et al. ENRICH: A promising oncology nurse training program to implement ASCO clinical practice guidelines on fertility for AYA cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2016.

Zill JM, Christalle E, Müller E, Härter M, Dirmaier J, Scholl I. Measurement of physician-patient communication—a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112637.

Bober SL, Reese JB, Barbera L, Bradford A, Carpenter KM, Goldfarb S, et al. How to ask and what to do: a guide for clinical inquiry and intervention regarding female sexual health after cancer. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2016;10:44–54.

Schover LR. Counseling cancer patients about changes in sexual function. Oncology (Williston Park). 1999;13:1585–91.

Acknowledgments

Jennifer Barsky Reese was supported by a Mentored Research Scholar Grant (MRSG-14-031-01-CPPB) from the American Cancer Society and by P30 CA006927 from the National Cancer Institute. The funding agencies had no role in the conduct of this study. We wish to thank Karenann Jurecki and Beth Lewis in the Fox Chase Talbot Research Library for their assistance with the searches.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 42 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reese, J.B., Sorice, K., Beach, M.C. et al. Patient-provider communication about sexual concerns in cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 11, 175–188 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0577-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0577-9