Abstract

Introduction

Sexuality is an important aspect of life involving physical, psychological, interpersonal, and behavioral aspects. The aim of this review was to examine the literature regarding sexuality in advanced cancer patients, after taking into consideration the principal changes produced by the disease and its treatment.

Methods

This review considered references through a search of PubMed by use of the search terms “advanced cancer,” “palliative care,” in combination with “sexuality” and/or “intimacy.”

Results

Surgery, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, radiotherapy, and drugs commonly given for the symptomatic treatment have relevant consequences on sexuality, also in the advanced stage of disease. Sexual dysfunction is a multifaceted issue and different causes may concomitantly have a role, including the psychological and clinical status. The existing clinical studies have shown important cultural barriers on sexuality. Sexuality is not considered a medical concern compared with the priority of treating cancer or symptoms. Although this issue is very private, unaddressed sexuality changes can be among the most negative influences on the social well being of a cancer patient. It is increasingly acknowledged that issues surrounding sexuality are an important factor in quality of life for patients with cancer and that sexuality is a legitimate area of concern in oncology and palliative care. Few studies have assessed sexuality in the advanced stage of disease. Nevertheless, advanced cancer patients are willing to talk about their sex lives and the impact of the disease on their sexual function.

Conclusions

To provide this component of care, professionals need to have good communication skills, an open and non-judgmental approach, and knowledge of the potential ramifications of disease and treatment of sexuality problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

According to World Health Organization, sexuality is a central aspect of human being throughout life and encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy, and reproduction [1]. Sexuality is a multidimensional issue, expressed by many socio-cultural aspects, such as thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviors, practices, roles, and relationship [2]. Sexuality has also been defined as the process of giving and receiving sexual pleasure and is associated with a sense of belonging or being accepted by another [3]. Intimacy has been described as the sharing of identity, closeness, and reciprocal rapport, more closely linked to communication issues rather than sexual function [4]. Although sexual intimacy is important, it is not the only form of intimacy. Different psychological and physical problems develop during the disease due to cancer itself or consequences of treatment and inevitably worsen in the advanced stage. The topic is even more rarely addressed in the advanced stage of disease and cancer practitioners falsely assume that those with advanced stage of disease are essentially “asexual.”

The aim of this review is to examine the different aspects of sexuality in advanced cancer patients, the possible factors influencing the development and persistence of sexual dysfunction. References for this review were found through a search of PubMed by use of the search terms “advanced cancer,” “palliative care,” in combination with “sexuality” and/or “intimacy.” References of the retrieved studies were also reviewed. Only articles published in English between 1985 and 2008 were included. Pertinent literature regarding persisting consequences of cancer on sexuality then reported in the advanced stage of disease was also selected.

Cancer and sexuality: general aspects

Sexual function is an aspect of quality of life that is often considered less important than treatment protocols and procedure during the illness and in the advanced stage when symptom control is of paramount importance [5]. Most health professionals fail to address sexuality in the clinical setting and feel more comfortable focusing on treatment outcomes than in addressing issues related to sexual behavior on the presumption that issues of survival overshadow sexuality [6]. Thus, cultural issues and poor knowledge relating to changes in a person’s sexuality during the cancer treatment or the advanced stage of disease provide barriers to open communication about sexuality [7]. Regretfully, many patients are disappointed by the lack of information, support, and practical strategies provided by health professionals to assist them to live with the sexual and intimate changes in the face of a life-limiting disease [8]. Indeed, current research suggests that patients are willing to discuss sexual concerns [9].

Data does show that sexuality declines after a cancer diagnosis and does not improve over time [10]. Cancer and its treatments impact sexuality and intimacy, regardless of age, race, sexual orientation, gender, or socioeconomic background [11]. It is estimated that 20–100% of cancer patients experience sexual dysfunction after treatment [12, 13]. It is very difficult to accurately predict how cancer and its treatment can affect sexuality, giving the individual meaning attributed to this term. All cancers and related treatments have the potential to affect sexuality. An individual’s sexual response can be affected in many ways which may have a reciprocal impact (see Table 1).

The causes of sexual dysfunction are often both physical, due to treatment and progression of disease, and psychological.

-

a)

Psychological issues

Cancer and its treatment can change the way one feels about him/herself (self-esteem). Body image dissatisfaction is a common effect of cancer and its treatment [14]. Cancer treatments may cause physical changes that affect how an individual sees his or her physical appearance. For example, women who have had a mastectomy have a greater need to talk about concerns than do their partners [2]. This view can make a man or woman feel sexually unattractive (see Table 2). Some of these changes, such as weight changes and hair loss, can be temporary. Permanent changes, particularly evident in the advanced stage of disease, can range from minor scarring to the loss of a body part [15]. The intense emotions that cancer can cause may also lower self-esteem, which can affect quality of life [3]. Long-term problems such as depression and anxiety inevitably develop. One may feel that he has lost some of his independence and can’t do things that he used to enjoy. Loss of sexual desire and a decrease in sexual pleasure are common symptoms of depression, and depression is more common in patients with cancer than in the general healthy population.

Cultural issues may strongly affect the sexual relationship. Patients who do not have a committed relationship may stop dating because they fear of being rejected by a potential new partner who will learn about their history of cancer. Some people have a feeling of being “unclean” after treatment or may have feelings of guilt from misbeliefs about the origin of the cancer. One of the most important factors in adjusting after cancer treatment is the patient’s feeling about his or her sexuality before being diagnosed with cancer. If patients had positive feelings about sexuality, they may be more likely to resume sexual activity after treatment for cancer.

Patients may feel so tired and worried that activities they used to find easy seem too difficult to do. Tiredness can make people lose interest in sex. Getting older is often associated with a decrease in sexual desire and performance. However, sex may be still important to the older person’s quality of life and the loss of sexual function can be distressing [16].

-

b)

Effects of disease and treatment

Surgery

Although any type of surgery can affect sexuality, even if it doesn’t involve the sex organs, cancer treatment that affects the genitals and breasts directly may cause quite marked changes [17]. Both males and females experience these. Women who had surgery to remove the uterus, ovaries, bladder, or other organs in the abdomen or pelvis may experience pain and loss of sexual function depending on the amount of tissue/organ removed [18]. Increased radicality of the surgery is associated with more sexual arousal impairment, presumably through effects on damaging autonomic nerve inputs. Modern surgical procedures are aimed at not damaging the nerves in this part of the body, but even so, women may find that their sensations during sex and orgasm are different after this type of operation. The removal of lymph glands may cause swelling in the area and in ankles and legs and some numbness may occur [19]. After vaginal reconstruction using a thigh flap, patients may feel a strange sensation in the inner thighs when they have sexual intercourse. Women have described this sensation as feeling as if their inner thighs are being stroked. It happens because the nerves that supply the thigh tissue are now part of the walls of the reconstructed vagina. The brain picks up this message and thinks that the leg is being touched. Women have also reported that they don’t feel that they can contract the muscles around the entrance to the vagina as easily as before their surgery.

Mastectomy produces a body change that can affect sexual arousal in many ways, particularly if patients were previously aroused by having breasts touched. The operation affects their image of themselves and patients may feel less womanly. Lumpectomy can still affect the way women feel about their bodies and may affect the sensations in the breast [8]. Malignant wounds in women with breast cancer may inhibit need for physical closeness and sexual activity [20].

In men, radical prostatectomy is frequently followed by difficulty getting or keeping an erection, due to damage to the nerves that control erection, in a large number of patients (up to 90%). This complication starts immediately after the surgery and can be permanent in a relevant number of cases. Radical prostatectomy damages nerves that make blood vessels open wider to allow more blood into the penis [21]. As a consequence, tissues do not get enough oxygen, cells die, and scar tissue forms that interfere with erectile function. Surgery that tries to avoid damaging the nerves can reduce the risk of problems. Newer nerve-sparing techniques for radical prostatectomy are being debated as a more successful approach for preserving erectile function than radiation therapy for prostate cancer. In men who can still have and maintain erections, it is very common to have dry ejaculations, as the semen passes into the bladder and not out through the penis. Patients will still have an orgasm, although it may feel slightly different. It does not cause any harm, but can be worrying if patients do not expect this to happen. These changes will mean that patients are infertile [19].

An abdomino-perineal resection can affect the nerves that control erection and ejaculation. Modern surgical procedures are aimed at not damaging the nerves in this part of the body but even so, many men will have erection problems [22]. Gonadal dysfunction is common in patients with a history of testicular cancer even when managed by orchidectomy alone. Co-treatment with chemotherapy in particular can result in additional impairment. Gonadal dysfunction reduces quality of life and has an adverse effect on patient’s health. [23]. If both testicles are removed, for example as a treatment for testicular cancer, the man will be infertile and may be unable to have an erection.

Incontinence has a devastating impact on patient’s sexuality, although this issue has relatively been unexplored. Incontinence may represent loss of control and dignity. Sometimes surgery is used to create a stoma on the abdominal wall because of bowel or bladder cancer or advanced cervical or ovarian cancer. In this situation there is a high chance of permanent damage to the blood supply and the nerves in the genital area. This may cause a man to have problems in getting and maintaining an erection. It is not clear how this type of operation affects arousal and orgasm in women. A stoma can make some lovemaking positions uncomfortable. If lymph nodes have been removed as part of surgical treatment, this can cause swelling in a nearby area of the body. For example, when lymph nodes are removed from under the arm as part of treatment for breast cancer, the affected arm may swell. If lymph nodes are removed from the groin, this may cause swelling of the legs. Lymphedema can affect the way that patients feel about their body and may make it difficult to use the affected part of the body [19]. The impact on masculinity or femininity is tremendous in patients with head and neck cancer. It is a devastating experience in relation to body image and sexuality. These patients often undergo facial reconstruction with a disappointing effect [24].

Effects of chemotherapy on sexuality

Common adverse effects of chemotherapy include feeling sick, weakness, depression, tiredness, and lack of energy, all factors which can reduce sex drive. Once chemotherapy is over, sex drive usually comes back in time [13]. Unfortunately, if the chemotherapy induced alopecia, or if patients have lost weight, or have a central line, they may feel very unsexy.

In women, chemotherapy can reduce the amount of hormones produced by the ovaries, changing monthly periods, which can sometimes stop altogether. It can cause the symptoms of an early menopause, including hot flushes, irritability, sleep disturbances, and vaginal dryness [4]. The loss of estrogen can cause shrinking, thinning, and loss of elasticity of the vagina, vaginal dryness, hot flushes, urinary tract infections, mood swings, fatigue, and irritability. Young women who have breast cancer and have had surgeries such as removal of one or both ovaries may experience symptoms related to loss of estrogen. These women experience high rates of sexual problems since there is a concern that estrogen replacement therapy, which may decrease these symptoms, could cause the breast cancer to return. Also, women who have graft-versus-host disease following bone marrow transplantation may develop scar tissue and narrowing of the vagina that can interfere with intercourse [25]. Vaginal thrush is common in women having chemotherapy, especially if they are taking steroids or powerful antibiotics to prevent infection. Vaginal infections, due to immunosuppression, may be of concern.

Men may find that their sex drive falls at the time of the therapy due to tiredness and possibly feelings of sickness. It usually returns to normal soon after the end of the therapy. Occasionally, chemotherapy may interfere with testosterone production, but this also usually goes back to normal in time [20]. Sexual problems such as loss of desire and erectile dysfunction are more common after a bone marrow transplant because of graft-versus-host disease or nerve damage [26].

Hormonal issues

Hormone therapies are treatments for cancer that use hormones or drugs that block hormones. Some of the side effects of these treatments can affect patients’ sex life [4]. Tamoxifen and anastrozole are commonly used hormonal therapy drugs often given as part of the treatment for breast cancer. They have fewer side effects than chemotherapy but can make some women have symptoms similar to those of the menopause. These can include vaginal soreness, dryness or discharge, atrophy of the vagina, and a drop in sex drive.

Although ovarian hormones play an important role in the maintenance of sexual health in women, a large body of evolving information suggests that these hormones may be necessary but not sufficient to overcome disorders of desire and arousal in women [27]. The link between ovarian hormones and sexuality is complex and controversial. For example, both hormones (estrogen and testosterone) are necessary to receive a meaningful benefit from additional androgen therapy. Moreover, testosterone therapy does not appear to increase serum concentrations of estradiol [12]. Furthermore, the benefit from testosterone therapy does not appear to be a result of increases in serum estradiol concentrations [28]. Thus providing supplemental estrogen to women who are postmenopausal is required to obtain a benefit from androgen therapy. However, it does not appear that androgen supplementation would be a viable option for women who must avoid estradiol replacement [29].

Men with complete remission of testicular cancer show endocrine abnormalities, such as above-normal gonadotropin levels and lowered testosterone, associated with a negative impact on the quality of life. Treatments to lower testosterone levels have major effects on a man’s sex life [28]. Patients change in libido or may not be able to get an erection. Patients may notice that they produce less semen, need to shave less often, and have less muscle strength. Some men may also develop breast swelling and tenderness. A man whose testicles have been removed may feel less masculine. Younger men do not always experience the same degree of sexual dysfunction [11].

Effects of radiotherapy

Like chemotherapy, radiation therapy can cause persistent adverse effects such as fatigue, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, and other symptoms that can decrease feelings of sexuality. Radiotherapy commonly causes fatigue which may last for several weeks or months. In this situation, patients may be too tired to actually have sex. For both men and women, radiotherapy to the pelvic area will cause infertility. Radiotherapy to other parts of the body may also give a dose to the sexual organs that will cause infertility. If they happen, these changes cannot be reversed and infertility will be permanent.

In women, any radiation to the pelvic area for cancer involving the rectum, bladder, or cervix, affects the ovaries and reduces the production of female hormones [30]. The production of hormones gradually decreases over about 3 months. This will cause symptoms of the menopause, such as hot flushes and mood swings. In the long term, the low hormone levels can increase the risk of weakened bones (osteoporosis) and heart disease. Radiation therapy to the pelvis can cause changes in the lining of the vagina. It becomes sore and tender in the early stages and for a few weeks afterward. Over time, this irritation may leave scarring. This makes the vagina narrower and less flexible resulting in pain with intercourse, infertility, and other long-term sexual problems. When radiotherapy is directed at the chest wall, the skin becomes red and irritated and the skin reaction may cause the skin to be dry and flaky. Fibrosis may occur later [31].

In men, radiotherapy may affect sexual function when it is given to the pelvic area for cancers of the prostate, rectum, and bladder [32]. Up to 30% of men will have problems getting or keeping an erection after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Radiotherapy to the pelvic area can reduce a man’s ability to have an erection [20]. The effects of radiation therapy on erectile function are very slow and gradual occurring for 2 or 3 years after treatment. Possible causes of sexual problems after radiation therapy include nerve injury, a blockage of blood supply to the penis, or decreased levels of testosterone. Sexual changes occur very slowly over a period of 6 months to 1 year after radiation therapy [21]. Brachytherapy is being used more often to treat prostate cancer [29]. With brachytherapy alone, ejaculation and erectile function are better preserved than when external radiation and/or hormone therapy are added. In men who can still have and maintain erections, it is very common to have dry ejaculations which is not harmful but can worry them if they don’t expect it. Some men feel a sharp pain as they ejaculate if they have recently had radiotherapy treatment. This is caused by radiation irritating the urethra [33].

Opioid treatment

Opioids may produce hormonal changes. Chronic exposure to high-dose oral opioid therapy may result in marked central hypogonadism and sexual dysfunction. Survivors of cancer who chronically consumed opioids experienced symptomatic hypogonadism with significantly higher levels of depression, fatigue, and sexual dysfunction [34]. Of interest, this effect is reversible with discontinuation of opioid therapy [35].

-

c)

Barriers in advanced cancer population

The same barriers to sexuality reported in oncologic population have been found in advanced cancer patients, despite the better communication skills and a dedicated environment, typical of palliative care settings [36]. Health professionals do not address the sexual concerns because of fears of being intrusive, personal discomfort, inadequate knowledge, time constraints, and poor confidence with intimate communication [37]. The discomfort of health professionals in addressing sexuality in advanced cancer patients is confirmed by the finding that only one out of ten patients in a palliative care setting had been asked about their sexuality [38]. Hospice environment also poses further problems because of the limited privacy, while patients in the home care setting have more freedoms and the privacy they desire [2]. However, most patients are willing to talk about their sex lives and the impact of the disease on their sexual function [39]. Sexuality continues to be important at the end of life, although it is often emotional connection to others that is more important than the physical expression [37]. Thus, within the patient’s ability to function and desire for it, sexuality should be acknowledged and included in the holistic patient management.

-

d)

Clinical studies in advanced cancer patients

While several studies have been published on sexual dysfunction that occurs with disease and treatment or cancer survivors [2, 23], very few articles have addressed sexuality or intimacy in advanced cancer patients in the literature. In palliative care population physical and emotional symptoms affect sexuality. Having advanced cancer means that cancer can’t be controlled, but does not mean that a patient is already terminally ill. Even if patients don’t feel like having sexual intercourse, they may still have sexual feelings even if they are very ill. Studies show that even terminally ill patients continue to have sexual thoughts and feelings and would value freedom for some sexual expression [37]. If cancer is in the advanced stage patients may have an even stronger need for intimacy than before they had cancer. Physical closeness, sharing feelings and touching may become very important. Knowing cancer can’t be cured can bring up some very strong emotions. This can be very difficult to cope with, especially if patients are single and don’t have the support of a caring partner [3].

Several factors may affect sexual function at the end of life, including psychological issues and clinical changes due to the illness and treatment which are able to amplify all the factors reported for cancer patients, previously examined. With important changes in health, advanced cancer patients often feel sick, weak, depressed, all of which can diminish sexual desires. Changes in social, work, family and marital role, fear of rejection due to the loss of body image, and poor interpersonal communication play a fundamental role. Persistent effects of chemotherapy or progression of disease, including weakness, nausea, weight loss, hair loss, intestinal symptoms, skin changes, altered sense of smell and taste, vaginal dryness, premature menopausal symptoms, interference with ejaculation, and testosterone deficiency, may strongly affect sexual function. Similarly, consequences of surgery, such as amputation of body parts, scars, ostomies, disruption of autonomic nervous system, pelvic adhesions, and scarring limit sexual function, as well as burns, destruction of neurovascular pathways, fatigue, nausea, vaginal fibrosis, and erectile dysfunction due to radiotherapy. Finally several agents, such as antidepressants, beta blockers, and opioids also decrease sexual desire or ability [34, 35].

Comorbidity and the relative treatment, particularly in aged population, contribute to sexual dysfunction [36]. Moreover, illness may impact couples’ relationships when communication with the partner is poor [40].

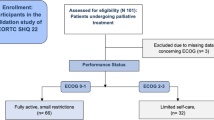

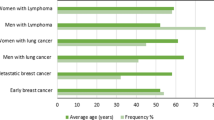

In a survey performed in a sample of 50 patients who gave their informed consent, recruited in different settings, including oncology wards, palliative care unit, day-hospital, outpatient clinic, and radiation center, irrespective of a patient’s age, sex, culture, partnership status, or stage of disease, cancer dramatically altered intimate and sexual aspects of a person’s life. Of interest, highly reflexive patients, mainly employed in specific jobs, had a desire for individualized patient-centered styles of health professionals’ communication about intimate and sexual change. In contrast, health professionals remained fixated on whether patients were capable of having sexual intercourse and on the impact of cancer treatment on menopause, erectile, or fertility status [41]. These data were confirmed in a survey performed by semi-structured participant interviews with a mixed population of cancer patients and professionals. Cancer profoundly changed intimates and sexual aspects of their life, irrespective of age, gender, culture, type of cancer, or partnership status. It was evident, a clear incongruence between the way patients and health professionals constructed sexuality and intimacy [5, 42]. In both studies some typical cluster themes emerged along the reflexive axis. The less reflexive patients stated that survival was more important than sexuality, or the expert opinion was relevant, while more reflexive patients preferred to search for options and negotiating communication. The study also revealed that the majority of health professionals embraced a less reflexive and more medicalized approach about patient issues of intimacy and sexuality after cancer, in contrast with expectations of patients [43]. Unexpectedly, in both studies no differences were found regarding the stage of disease.

However, in a controlled study of a mixed population of cancer patients recruited in oncologic units and hospices, palliative care patients were the most impaired with respect to quality of life, emotional distress, and sexual dysfunction [39]. Of interest, this study confirmed that addressing potential sexual problems during the course of disease may give patients confidence to discuss such issues as they occur, thus avoiding embarrassment or aggravation of the problems later in their illness.

A qualitative study investigating the meaning of sexuality to ten palliative care patients showed that sexuality was an important aspect of their life, even in the last weeks and days of life. Patients’ experience of sexuality changed over time, from expression that included sexual intercourse until non-physical expressions of closeness. Only one subject had previously been asked about sexuality as part of their clinical care. Lack of privacy, shared rooms, staff intrusion, and single beds were considered barriers to expressing sexuality in hospital and hospice settings. A holistic approach to palliative care would include opportunities to discuss the impact of their sexuality [38].

Conclusion

The impact of cancer and its treatment on a person’s sexual function has been largely debated throughout the literature. Information regarding such aspects in advanced cancer patients is still lacking although sexual dysfunction is an inevitable problem for patients with advanced cancer. Existing data regarding palliative care population are scarce, limited to data of semi-structured interviews or low number of patients to provide clear information about needs and possible interventions. Unfortunately, sexual problems are often not identified by professional as a priority and most patients will receive poor help in dealing with the effects of cancer and its treatment on intimacy, as social norms, myths, and assumptions may prevent professionals from broaching these issues [21, 36]. Indeed, it is increasingly acknowledged that issues surrounding sexuality are an important factor in quality of life for patients with cancer and that sexuality is a legitimate area of concern in oncology and palliative care. It is possible to state the belief and assumption of ageists that sexuality and intimacy of the advanced cancer patients in the face of life-threatening disease, which are relevant barriers to overt communication on an important topic for patients, are not made by health professionals a patient priority.

Questions concerning sexual difficulties should be incorporated into the initial evaluation of patients and the following assessment. To provide this component of care, professionals need to have good communication skills, an open and non-judgmental approach, and knowledge of the potential ramifications of disease and treatment on sexuality. It is important that all patients have access to professionals who are knowledgeable and competent to assist them to cope with issues of intimacy and sexuality. Prospective studies on a large sample of patients are ongoing to provide further information about this challenging topic in a palliative care population.

References

World Health Organization. Sexual Health. http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/gender/sexual_health.htlm

Hughes M (2000) Sexuality and the cancer survivor. Cancer Nurs 23:477–482

Shell JA (2008) Sexual issues in the palliative care population. Semin Oncol Nurs 24:131–134

Ganz P, Rowland J, Desmond K, Meyerowitz B, Wyant G (1998) Life after breast cancer: understanding women’s health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol 16:501–514

Hordern A (2008) Intimacy and sexuality after cancer. A critical review of the literature. Cancer Nurs 31:E9–E17

Caffo O, Fellin G, Bolner A, Coccarelli F, Divan C, Frisinghelli M, Mussari S, Ziglio F, Malossini G, Tomio L, Galligioni E (2006) Prospective evaluation of quality of life after interstitial brachytherapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 66:31–37

Hordern A (2000) Intimacy and sexuality for the woman with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 23:230–236

Hordern A, Street A (2007) Issues of intimacy and sexuality in the face of cancer. Cancer Nurs 30:E11–E18

Katz A (2005) The sounds of silence: sexuality information for cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 23:238–241

Yurek D, Farrar W, Andersen BL (2000) Breast cancer surgery: comparing surgical groups and determining individual differences in postoperative sexuality and body change stress. J Consult Clin Psychol 68:697–709

Bolte S, Zebrack B (2008) Sexual issues in special population: adolescent and young adults. Semin Oncol Nurs 24:115–119

McKee A, Schover L (2001) Sexuality rehabilitation. Cancer 92:1008–1012

Tierney KD (2008) Sexuality: a quality of life issue for cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs 24:71–79

DeFrank J, Bahn Metha C, Stein CK, Baker F (2007) Body image dissatisfaction in cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 34:E36–E41

Kagan S, Holland N, Chalian A (2008) Sexual issues in special population: geriatric oncology-sexuality and older adults. Semin Oncol Nurs 24:120–126

Lunden-Nielsen B, Muller K, Adamsen L (2005) Malignant wounds in women with breast cancer: feminine and sexual perspective. J Clin Nurs 14:56–64

Bodurka DC, Sun CC (2006) Sexual function after gynecologic cancer. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 33:621–630

Bodurka DC, Pieterse SCC, QD MCP, ter Kuile MM, Lowik M, van Eijkeren MA, Trimbos JB, Kenter GG (2006) An observational longitudinal study to evaluate miction, defecation, and sexual function after radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 16:1119–1129

Waxman E (1993) Sexual dysfunction following treatment for prostate cancer: nursing assessment and interventions. Oncol Nurs Forum 20:1567–1571

Symon Z, Daignault S, Symon R, Dunn RL, Sanda MG, Sandler HM (2006) Measuring patients' expectations regarding health-related quality-of-life outcomes associated with prostate cancer surgery or radiotherapy. Urology 68:1224–1229

Fisher SE, Daniels IR (2006) Quality of life and sexual function following surgery for rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 8(Suppl 3):40–42

Shell JA (2002) Evidence-based practice for symptom management in adults with cancer: sexual dysfunction. Oncol Nurs Forum 29:53–69

Metcalf M, Fishman S (1985) Factors affecting the sexuality of patients with head and neck cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 12:21–25

Yi JC, Syrjala KL (2009) Sexuality after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer J 5:57–64

Claessens JJ, Beerendonk CC, Schattenberg AV (2006) Quality of life, reproduction and sexuality after stem cell transplantation with partially T-cell-depleted grafts and after conditioning with a regimen including total body irradiation. Bone Marrow Transplant 37:831–836

Ganz P, Greendale G (2007) Female sexual desire—beyond testosterone. J Natl Cancer Inst 99:659–661

Wilke DR, Parker C, Andonowski A, Tsuji D, Catton C, Gospodarowicz M, Warde P (2006) Testosterone and erectile function recovery after radiotherapy and long-term androgen deprivation with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists. BJU Int 97:963–968

Barton DL, Wender DB, Sloan JA, Dalton RJ, Balcueva EP, Atherton PJ, Bernath AM Jr, DeKrey WL, Larson T, Bearden JD 3rd, Carpenter PC, Loprinzi CL (2007) Randomized controlled trial to evaluate transdermal testosterone in female cancer survivors with decreased libido; North Central Cancer Treatment Group protocol N02C3. J Natl Cancer Inst 99:672–679

Donovan KA, Taliaferro LA, Alvarez EM, Jacobsen PB, Roetzheim RG, Wenham RM (2007) Sexual health in women treated for cervical cancer: characteristics and correlates. Gynecol Oncol 104:428–434

Saewong S, Choobun T (2005) Effects of radiotherapy on sexual activity in women with cervical cancer. J Med Assoc Thai 88(Suppl 2):S11–S15

Pietrzak L, Bujko K, Nowacki MP, Kepka L, Oledzki J, Rutkowski A, Szmeja J, Kladny J, Dymecki D, Wieczorek A, Pawlak M, Lesniak T, Kowalska T, Richter P, Polish Colorectal Study Group (2007) Quality of life, anorectal and sexual functions after preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer: report of a randomised trial. Radiother Oncol 84:217–225

Namiki S, Satoh T, Baba S, Ishiyama H, Hayakawa K, Saito S, Arai Y (2006) Quality of life after brachytherapy or radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer: a prospective longitudinal study. Urology 68:1230–1236

Rajagopal A, Bruera ED (2003) Improvement in sexual function after reduction of chronic high-dose opioid medication in a cancer survivor. Pain Med 4:379–383

Rajagopal A, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Palmer JL, Kaur G, Bruera E (2004) Symptomatic hypogonadism in male survivors of cancer with chronic exposure to opioids. Cancer 100:851–858

Stausmire JM (2004) Sexuality at the end of life. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 21:33–38

Redelman MJ (2008) Is there a place for sexuality in the holistic care of patients in the palliative care phase of life? Am J Hosp Palliat Med 25:366–371

Lamieux L, Kaiser S, Pereira J, Meadows LM (2004) Sexuality in palliative care: patient perspectives. Palliat Med 18:630–637

Ananth H, Jones L, King M, Tookman A (2003) The impact of cancer on sexual function: a controlled study. Palliat Med 17:202–205

Rowland J (1994) In sickness and in health: the impact of illness on couples’ relationships. J Marital Fam Ther 20:327–332

Hordern A, Currow D (2003) A patient-centered approach to sexuality in the face of life-limiting illness. Med J Aust 179:S8–S11

Hordern A, Strett A (2007) Constructions of sexuality and intimacy after cancer: patient and health professional perspectives. Soc Sci Med 64:1704–1718

Hordern A, Street A (2007) Communicating about patient sexuality and intimacy after cancer: mismatched expectations and unmet needs. Med J Aust 186:224–227

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mercadante, S., Vitrano, V. & Catania, V. Sexual issues in early and late stage cancer: a review. Support Care Cancer 18, 659–665 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0814-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0814-0