Abstract

Purpose

Sexual dysfunction among patients with colorectal cancer is frequently reported. Studies examining patients’ sexual health care needs are rare. We examined the sexual health care needs after colorectal cancer treatment according to patients, partners, and health care professionals (HCPs). Factors that impede or facilitate the quality of this care were identified.

Method

Participants were recruited from three Dutch hospitals: St. Elisabeth, TweeSteden, and Catharina hospitals. Patients (n = 21), partners (n = 9), and 10 HCPs participated in eight focus groups.

Results

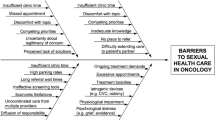

It is important to regularly evaluate and manage sexual issues. This does not always occur. Almost all participants reported a lack of knowledge and feelings of embarrassment or inappropriateness as barriers to discuss sexuality. HCPs reported stereotypical assumptions regarding the need for care based on age, sex, and partner status. The HCPs debated on whose responsibility it is that sexuality is discussed with patients. Factors within the organization, such as insufficient re-discussion of sexuality during (long-term) follow-up and unsatisfactory (knowledge of the) referral system impeded sexual health care. The HCPs could facilitate adequate sexual health care by providing patient-tailored information and permission to discuss sex, normalizing sexual issues, and establishing an adequate referral system. It is up to the patients and partners to demarcate the extent of sexual health care needed.

Conclusions

Our findings illustrate the need for patient-tailored sexual health care and the complexity of providing/receiving this care. An adequate referral system and training are needed to help HCPs engage in providing satisfactory sexual health care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is an increasing awareness that patients coping with cancer may have sexual health care needs [1]. Previous studies have shown that patients with breast cancer, gynecological cancer, or prostate cancer may need informational support and treatment to optimize the patients’ sexual functioning and/or the quality of sexual life [1]. However, these needs may not be adequately met [1].

Although sexual dysfunctions among patients with colorectal cancer are frequently reported [2], studies examining the sexual health care needs of these patients are rare [3–5]. One study investigated the informational needs of patients and reported that 55 % of them did not remember receiving any information on how cancer or cancer treatment may affect their sexual functioning, while 58 % rated this topic as important (somewhat—very important) [3]. In addition, patients’ unmet sexual health care needs were positively related to psychological symptom distress, but negatively related to age [4]. To our knowledge, only one study noted an impact of surgery or a stoma on the sexual relationship [5]. However, the two latter studies did not provide an in-depth view since the sexual health care needs were examined as a secondary objective. Furthermore, studies examining both patients and partners are lacking even though coping with cancer is probably a dyadic affair [6, 7]. Finally, there may be a mismatch in expectations between patients and partners and health care professionals (HCPs) with regard to the necessity for sexual health care [1, 8].

Due to the abovementioned reasons, it is important to ascertain the sexual health care needs of patients and partners coping with colorectal cancer and to explore when and by whom these sexual issues could be evaluated and managed [9, 10]. Knowledge of the barriers and facilitators associated with providing or receiving adequate sexual health care may enable patients, partners, and HCPs to overcome these issues. Therefore, the aim of the current focus group study was to examine (a) the sexual health care needs according to patients, partners, and HCPs and (b) factors that impede or facilitate the sexual health care.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were recruited from the St. Elisabeth Hospital (Tilburg, the Netherlands), TweeSteden Hospital (Tilburg and Waalwijk, the Netherlands), or Catharina Hospital (Eindhoven, the Netherlands). First, the patients’ medical records were reviewed in order to determine the patients’ eligibility. Eligible participants had to be (a) diagnosed with colorectal cancer between January 2010 and February 2012 or be the partner of an eligible patient diagnosed with colorectal cancer within this time frame and (b) aged between 18 and 75 years. Persons were excluded if they (a) had metastatic colorectal cancer or their partner had metastatic colorectal cancer, (b) were physically not fit enough to attend the focus group, (c) had a history of mental disease or cognitive problems, or (d) had insufficient knowledge of the Dutch language. One of the researchers (MJT) contacted the eligible participants to explain the purpose of the study and invited them to participate. In order to ensure a wide variety of experiences to be represented, potential participants were informed that having sexual health care needs and/or being sexually active was not a prerequisite to participate in this study. In addition, patients and partners were selected based on their sex, age, and tumor type (if applicable) in order to attain a fair representation of the colorectal cancer patient population and their partners. To rule out selection bias, the partners were still invited to participate when patients declined participation and vice versa. A purposive sampling method was applied. Purposive sampling implies that the recruitment of participants was stopped after the intended number of participants and sufficient diversity between the participants in the focus groups was achieved. The participating HCPs were invited by two members of the research team (JAR and HJTR). JAR and HJTR selected HCPs based on their expertise and experience working with the colorectal cancer patient population. The medical ethical committee approved the study. All participants gave written informed consent. Participation was voluntarily; no financial reward was given.

Focus group meetings

Conducting focus groups is one of the most used methods in qualitative research [11]. Focus groups facilitate the in-depth exploration of a person’s perspective through group interaction [12]. Since sexual health care needs were the topic of the focus groups, it was thought that participants would share information more easily when not in the presence of their partner, someone of the opposite sex, or their HCP. Therefore, patients, partners, and HCPs were interviewed separately. In addition, the patient and partner groups were sex-specific. Usually, six to eight participants are invited per focus group [12]. However, given the sensitive topic, we allowed fewer participants per focus group. After eight sessions, data saturation was reached [13]. Each focus group was guided by a focus group moderator (MJT). The moderator was assisted by a student who took notes. The moderator started each focus group by explaining the purpose of the study followed by an introductory round in which each of the participants briefly shared their experiences. During the focus groups, two main questions were asked: “Which sexual health care needs did you have during the course of treatment or do you still have?” and “During which treatment phase did you need/receive this sexual health care?” Follow-up questions were asked to capture the experiences of the participants and their view on how to improve sexual health care (if needed). The focus group structure was the same for each focus group. The focus groups took about 90 min and were audiotaped with the participants’ permission.

Questionnaire

Patients and partners completed questions assessing sociodemographic factors (i.e., age, sex, marital status, and educational level). In addition, they rated on a 10-point scale (a) the importance of sexuality, (b) the severity of sexual problems, and (c) the influence of sexual problems on their quality of life. For the item on the importance of sexuality, a higher score indicated a higher importance. For the latter two questions, a higher score indicated more severe sexual problems and a bigger influence of these problems on quality of life, respectively.

Data analysis

The focus group meetings were analyzed using a grounded theory approach [13, 14]. Data analysis proceeded stepwise. First, the focus groups were transcribed verbatim. Next, open coding was used in order to identify the needs and determinants for change. Subsequently, the determinants were grouped into barriers and facilitators. Next, these barriers and facilitators could be grouped according to the model of Wensing et al. [15, 16] who described factors that impede or facilitate change in the care system: (a) individual factors (e.g., motivational, cognitive, or behavioral), (b) social factors (e.g., professional teams, professional development, and professional networks), (c) organizational factors (e.g., organizational processes, structure of the organization and work processes, and available resources), and (d) societal factors (e.g., financial factors, law and regulations). Two authors (MJT and BLDO) independently reviewed and coded each of the transcripts and ensured data saturation. In addition, these authors discussed the different sets of coding. When coding disagreements arose, the authors discussed the responses and selected the most appropriate code for each response. After this discussion, the transcripts were reread and recoded. Analyses were done using color coding in Microsoft Word and Excel.

Results

In total, 21 patients and nine partners participated (see Fig. 1 and Table 1). For the patients and partners, the sociodemographic characteristics as well as the scores reflecting the importance of sexuality, the severity of sexual problems, and the influence of sexual problems on their quality of life are presented in Table 1. The clinical characteristics of the patients are also reported in Table 1. Ten HCPs participated: two surgeons, one gynecologist, one gynecologist/oncologist, a urologist, two sexologists/psychologists, a physician assistant, a nurse practitioner, and a stoma nurse.

The sexual health care needs according to patients, partners, and HCPs

Survival seems to be the main priority for patients and partners, especially during treatment and the first months after treatment. However, sexuality may regain a more prominent position in the couples’ life after treatment. Patients and partners especially considered being intimate (e.g., hugging and kissing) and having a good relationship as important. Moreover, they often rated intimacy as more important than being able to have sexual intercourse.

Patients and partners both acknowledged the importance of receiving sexual health care. They reported having frank conversations about the possible consequences of colorectal cancer and its treatment on sexual function and/or the quality of sexual life as an important need. Since intimacy was often the main priority, they stated that these conversations should not focus solely on potential sexual dysfunctions but also on the psychosexual changes that may occur. Patients and partners also reported a need for (knowledge of the) treatment options if a sexual dysfunction or sexual problem occurs. The HCPs were aware that the sexual health care could be further improved both on an informational and a treatment level. However, all participants acknowledged a number of barriers to improving sexual health care. They reported similar individual and organizational factors that could impede or facilitate change. Therefore, the results are presented per factor. Within these factors, few sex- or role-specific (patient–partner–HCP) themes were reported. If a theme was only applicable for a subgroup of participants, then this is explicitly stated in the text.

Individual factors

Patients and partners were not always able to recall if they received information on the potential sexual consequences of treatment. Especially, the potential consequences of (neo)adjuvant therapy were reported as unknown. Knowledge on the available health care for sexual problems was also limited. Patients and partners reported this insufficient knowledge as a barrier to discuss their sexual health care needs with their HCP. Furthermore, the couples mentioned that sexuality is still a taboo; therefore, they felt embarrassed to discuss their sexual problems. In addition, they considered it as inappropriate to discuss sexuality with their HCPs since the main goal of treatment seems to be survival. The partners felt that they had to be strong for the patient and that the patient’s needs were most important, so they discarded their own sexual needs (Table 2).

The HCPs agreed that it is important to provide adequate sexual health care. However, they reported several barriers for providing this type of care. Most HCPs felt that they are insufficiently equipped to have in-depth discussions about sexuality or felt that it is outside their purview of care. The HCPs also reported several beliefs that made them reluctant to discuss sexuality (a) a feeling of inappropriateness to discuss sexuality since survival is the primary concern; (b) a fear to cause discomfort due to the private nature of the conversation, especially when other family members (e.g., children) are present; and (c) sexuality was sometimes seen as irrelevant based on the patients’ age, gender, or relationship status (Table 2).

The participants reported that discussing sexuality might become more easy if the HCPs (a) initiate and encourage the discussion without making any stereotypical assumptions, (b) normalize concerns by providing straightforward information on the possible sexual consequences of treatment and treatment options in case sexual problems arise, (c) give couples explicit permission to raise sexual issues at any time, (d) possess an open-minded attitude, (e) maintain a personalized approach, (f) be able to create a safe environment by placing the discussion not only into the context of the patient’s disease but also in the context of the couples’ lives; and (g) pay attention to psychosexual changes instead of focusing solely on clinical outcomes. Subsequently, it is up to the couples to demarcate the depth of the sexual health care needed. Thus, discussing sexuality was seen as a shared responsibility of all participants (Table 2).

Social factors

Having a professional multidisciplinary team within the hospital might facilitate providing adequate sexual health care, especially when this team adopts a holistic patient approach. Among the HCPs, there was a debate on whose responsibility it was to discuss sexuality. However, the patients and partners suggested that the HCPs of each discipline could discuss the possible consequences of their treatment modality and evaluate the patients’ sexual health during follow-up. In this way, the couples expected to receive patient-tailored information. For instance, sexual issues accompanied with having a stoma only have to be discussed with patients with a stoma. Furthermore, the HCPs acknowledged that they could further improve their professional development by attending courses on how to provide (limited) information and how to evaluate sexual issues. In addition, learning to recognize the boundaries of the HCPs own profession and the possibilities of other HCPs active in oncologic care may enable the HCPs to make a timely referral if more extensive treatment is needed. The HCPs believed that the professional network as a whole could intensify the awareness that providing sexual health care is an important aspect of cancer care (Table 3).

Organizational factors

Establishing a primary contact person for the couples was seen as an organizational process that could advance the sexual health care. The structure of the organization could further benefit from sufficient time to discuss sexuality during the existing consults. However, it is important to carefully select the information given during these consults in order to avoid an information overdose. Therefore, a structural re-discussion of sexuality during (long-term) follow-up is essential. Furthermore, improving the (awareness of) available resources might enable HCPs to provide better sexual health care. Personalized information in writing could for instance complement the verbal information. In addition, the sexologists pointed out that the HCPs have to be able to identify existing problems; however, if psychosexual counseling (e.g., by a sexologist) or treatment for dysfunctions (e.g., by a gynecologist or urologist) is needed, then the HCPs should be aware of the possibilities for referral. Finally, patients and partners mentioned a potential role for their general practitioner in the management of their sexual health care needs. The general practitioner could play a key role in observing potential sexual problems and the referral of patients (Table 3).

Societal factors

Societal factors were sporadically mentioned. For instance, one of the HCPs stated that the psychosexual care is largely covered by the health care insurance. However, another HCP mentioned that they can only provide limited care to the partner (i.e., Medical Treatment Agreements Act). Finally, some patients said that they could benefit from sexual aids (e.g., lubricants); however, buying these aids was considered to be difficult and embarrassing. Therefore, they wondered if the HCPs could prescribe sexual aids in order to increase the accessibility (Table 3).

Discussion

Patients and partners coping with colorectal cancer have sexual health care needs that are not always adequately met. While all patients and partners stated that it was important to have their sexual health care needs evaluated and managed, some HCPs wrongfully assumed that elderly, widowed, or female patients might have a lower need for sexual health care. Therefore, there was a mismatch between patients, partners, and HCPs with regard to the importance of providing/receiving adequate sexual health care in these specific patient populations. Several barriers to and facilitators for change were identified. Almost all participants reported a lack of knowledge and unsatisfactory communication skills as important barriers, while the HCPs (except for the psychologist/sexologist) additionally reported a lack of knowledge with regard to the referral possibilities. In addition, as stated above, some beliefs made the HCPs decide that discussing sexuality was not important which impeded the probability that sexual issues were discussed. Finally, resources, such as a good referral and consultation system and training are needed to help the HCPs engage in providing satisfactory sexual health care.

Even though we did not explicitly ask the participants about the factors that might impede or facilitate change, we were able to apply the theoretical framework of Wensing et al. [16]. Logically, the patients and partners were more concerned on the dynamics between the patient/couple and the HCP, while the HCPs were also more concerned with organizational and social issues. Societal factors were only sporadically mentioned. Therefore, future studies should investigate these societal factors more explicitly.

Our findings corroborate previous studies among other types of cancer [1]. For instance, the need for sexual health care has been found quite consistently in studies evaluating the sexual health care needs of primarily breast, gynecological, or prostate cancer patients (for an overview, we refer to Park, Norris, and Bober 2009) [1]. These studies reported several aspects, such as insufficient knowledge about the potential sexual consequences of cancer treatment and beliefs about sexuality as barriers to satisfactory sexual health communication [1]. Furthermore, the need for sufficient time during consults and adequate recourses (such as a good referral system) are previously reported as facilitators [1]. These results suggest that the majority of the sexual health care needs are applicable across cancer types and across (Western) countries. However, each cancer type may have additional disease-specific aspects that need to be taken into account. For instance, the participants in our study reported a need for information on how to have an intimate relationship while having a stoma (if applicable). In addition, individual barriers that may arise in the colorectal cancer patient population, such as assumptions based on age, sex, and partner status were identified.

Overall, the patients and partners stated that it is important that they are adequately informed and that their sexual health care needs are carefully evaluated and managed; however, they also said that it is up to them to determine the extent of health care wanted. It is important to keep in mind that there may not always be a need for help. Based on the need for tailored sexual health care, the adoption of a stepped care program, such as the Extended PLISSIT (Ex-PLISSIT) model may improve the sexual health care [17]. The traditional PLISSIT model developed by Annon follows a stepwise approach in which various levels of discussion or treatment are used [18]. If a lower order level is insufficient, then a higher order level can be deployed (for examples, see Katz [19]). Although this model is widely used, the applicability for patients with colorectal cancer has only recently received attention [20, 21]. For instance, a recent intervention study reported that patients with a stoma who received more psycho-education with regard to sexuality had better sexual satisfaction [20]. The acronym PLISSIT signifies the four levels of intervention: permission (P), limited information (LI), specific suggestions (SS), and intensive therapy (IT). The Ex-PLISSIT model extends the original model by emphasizing the role that permission giving plays at all stages by postulating that each stage is underpinned by permission giving [17]. In addition, intensive therapy may be used at any stage. If the HCP is challenged with something they feel unable to deal with, it is important that they refer to the patient to a colleague who is better qualified, regardless of stage. Finally, the Ex-PLISSIT model enables practitioners to use reflection and review to develop their own practice. In this way, providing sexual health care becomes a shared responsibility, which is also time effective. If needed, psychosexual counseling can be combined with medical treatment (e.g., phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor—PDE5-Is, vacuum erection devices, and lubricants). Although the PLISSIT model provides a framework for discussing sexual issues, it does not provide the clinical knowledge and communication skills to exploit this dialogue in an effective manner [21]. Thus, providing training to HCPs could beneficial, especially since the HCPs in our study stated that they could additionally benefit from education focused on improving their communication skills with regard to these domains (if needed).

This study contributed to the current literature since it assessed an important, but still under evaluated, field of research namely the sexual health care needs of patients with colorectal cancer and their partners, especially since we not only examined the patients’ perspective but also that of the partners and HCPs. In addition, this study not only included partnered participants, regardless of their level of sexual activity, but also single and widowed patients. Another important strength of this study is the qualitative design. Moreover, the semistructured qualitative design of this study facilitated an in-depth exploration of the sexual health care needs. We noticed that participants felt free to share their experience, which facilitated frank in-depth conversations. We conducted the focus groups in a standardized manner in order to keep information gathered and style of questioning consistent (e.g., used the same moderators). Furthermore, our study strengthens the general belief that the majority of the sexual health care needs are applicable across cancer types and across (western) countries. Hopefully, our study challenges HCPs to begin to evaluate their own needs for information, education, and skill training, along with affirmation from the patients and partners that sexuality is an important area of a quality of life that should be discussed during and after treatment. Finally, the results of this study allowed us to provide clear recommendations for both research and clinical practice (e.g., the use of the Ex-PLISSIT model) and questions for future research (e.g., the need to include ethnic minorities, see below).

However, there are also some limitations and still remaining questions for future research that need to be addressed. With a response rate of 51 %, the possibility of response bias has to be recognized. Even after emphasizing that having sexual health care needs and/or being sexually active was not a prerequisite to participate, the majority of patients and/or partners that declined participation said that they were not interested in discussing sexual health care needs. It might be that these patients and partners felt embarrassed to talk about sexuality. In addition, our study population unfortunately consisted solely of Caucasian participants since the inclusion of ethnic minorities was impeded by the fact that sufficient knowledge of the Dutch language was an inclusion criterion. Therefore, future studies are needed to examine the sexual health care needs and the determinants for change of participants with other ethnic backgrounds. Finally, the primary aim of the focus groups was to address the sexual health care needs in general as opposed to participants’ own private needs/functioning; therefore, we obtained limited quantitative information (i.e., the importance of sexuality, the severity of sexual problems, and the influence of sexual problems on their quality of life). Future research should evaluate the sexual functioning and quality of sexual life of this patient group more in-depth.

In the future, it could be beneficial when sexual health is included as a theme in the national guidelines on (colorectal) cancer. Nowadays, in the Netherlands sexuality is only represented in the Dutch Nursing guidelines [22]. In that way, quality indicators can be developed which can be used to evaluate the quality of care at a national level. These quality indicators can be used to highlight potential quality concerns, while information on barriers and facilitators can guide the selection of implementation strategies to improve sexual health care [15, 16].

In conclusion, our findings illustrate the need for patient-tailored sexual health care and the complexity of providing or receiving this care. An adequate referral and consultation system and training are needed to help HCPs engage in providing satisfactory sexual health care.

References

Park ER, Norris RL, Bober SL (2009) Sexual health communication during cancer care: barriers and recommendations. Cancer J 15:74–77. doi:10.1097/PPO.0b013e31819587dc

Traa MJ, De Vries J, Roukema JA, Den Oudsten BL (2012) Sexual (dys)function and the quality of sexual life in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 23:19–27. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr133

Flynn KE, Reese JB, Jeffery DD, Abernethy AP, Lin L, Shelby RA, Porter LS, Dombeck CB, Weinfurt KP (2012) Patient experiences with communication about sex during and after treatment for cancer. Psychooncology 21:594–601. doi:10.1002/pon.1947

Li WW, Lam WW, Au AH, Ye M, Law WL, Poon J et al (2012) Interpreting differences in patterns of supportive care needs between patients with breast cancer and patients with colorectal cancer. Psychooncology 22:792–798. doi:10.1002/pon.3068

Hall S, Gray N, Browne S, Ziebland S, Campbell NC (2012) A qualitative exploration of the role of primary care in supporting colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 20:3071–3078. doi:10.1007/s00520-012-1434-7

Traa MJ, De Vries J, Roukema JA, Den Oudsten BL (2013) Dyadic coping and relationship functioning in couples coping with cancer: a systematic review. Posterior Presentation, 6th Biennal Cancer Survivorship Research Conference, Arlington, Virginia

Berg CA, Upchurch RA (2007) Developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychol Bull 133:920–954

Hordern AJ, Street AF (2007) Communicating about patient sexuality and intimacy after cancer: mismatched expectations and unmet needs. Med J Aust 186:224–227

Romito F, Corvasce C, Montanaro R, Mattioli V (2011) Do elderly cancer patients have different care needs compared with younger ones? Tumori 97:374–379. doi:10.1700/1125.12410

Rutten LJ, Arora NK, Bakos AD, Aziz N, Rowland J (2005) Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: a systematic review of research (1980–2003). Patient Educ Couns 57:250–261

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19:349–357

Krueger RA (1988) Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Sage, Newbury Park

Corbin J, Strauss A (1990) Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual Sociol 13:3–21

Glaser BG, Strauss A (1967) Discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. Sociology, Mill Valley

Grol R, Wensing M (2004) What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. Med J Aust 180:s57–s60

Wensing M, Bosch M, Foy R et al (2005) Factors in theories on behavior change to guide implementation and quality improvement in healthcare. Centre for Quality of Care Research, Nijmegen

Taylor B, Davids S (2007) The extended PLISSIT model for addressing the sexual wellbeing of individuals with an acquired disability or chronic illness. Sex Disabil 25:135–139

Annon J (1976) The PLISSIT model: a proposed conceptual scheme for the behavioural treatment of sexual problems. J Sex Educ Ther 2:1–15

Katz A (2005) The sounds of silence: sexuality information for cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 23:238–241

Ayaz S, Kubilay G (2009) Effectiveness of the PLISSIT model for solving the sexual problems of patients with stoma. J Clin Nurs 18:89–98. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02282.x

Hayter M, Ayaz S, Kubilay G (2009) Effectiveness of the PLISSIT model for solving the sexual problems of patients with stomas. J Clin Nurs 18:154–156. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02626.x

Dutch guidelines nursing care: changed sexual functioning. http://www.oncoline.nl/veranderd-seksueel-functioneren. Accessed May 22 2013

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (UvT 2009–4495) to Brenda Den Oudsten, Jan Anne Roukema, and Jolanda De Vries. We thank all patients, partners, and HCPs for their participation. In addition, we thank the following hospitals for their cooperation: Catharina Hospital (Eindhoven), St. Elisabeth Hospital (Tilburg), and TweeSteden Hospital (Tilburg and Waalwijk). Finally, we would like to thank Marianne De Vries, Marieke Van Der Sanden, and Lindy Arts for their help in transcribing the focus groups verbatim and for their assistance during the focus groups.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have conflicts of interest. The authors have full control of all primary data, and if needed, we allow the journal to review the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Traa, M.J., De Vries, J., Roukema, J.A. et al. The sexual health care needs after colorectal cancer: the view of patients, partners, and health care professionals. Support Care Cancer 22, 763–772 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-2032-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-2032-z