Abstract

Purpose

One-anastomosis-gastric-bypass (OAGB) has become a common bariatric procedure worldwide. Marginal ulcers (MU) are a significant non-immediate complication of gastric bypass surgeries. There seems to be concern among surgeons that MU are more common after OAGB compared with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) due to the constant and extensive exposure of the anastomosis to bile. The aim of this study was to compare the incidence, presentation, and management of MU between the two surgeries.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective study of prospectively collected data was performed to include all consecutive patients between 2010 and 2020, who underwent elective OAGB or RYGB at our institution. Patients diagnosed with symptomatic MU were identified. Factors associated with this complication were assessed and compared between the two surgeries.

Results

Symptomatic MU were identified in 23/372 OAGB patients (6.2%) and 35/491 RYGB patients (7.1%) (p = 0.58). Time to ulcer diagnosis was shorter in OAGB patients (12 ± 11 vs. 22 ± 17 months, p < 0.01). Epigastric pain was the common symptom (78% OAGB vs. 88.5% RYGB, p = 0.7) and approximately 15% of ulcers presented with perforation upon admission (17% vs.11.4%, p = 0.7). Re-operation was required in 5/23 OAGB (21.7%) and 6/36 RYGB (17%) patients (p = 0.11) while the rest of the patients were managed non-operatively.

Conclusions

The risk of developing a marginal ulcer is similar between patients who underwent OAGB and RYGB. Patients diagnosed with MU following OAGB tend to present earlier; however, the clinical presentation is similar to RYGB patients. The management of this serious complication seems to be associated with acceptable outcomes with comparable operative and non-operative approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obesity is a modern-day global epidemic with a worldwide trend of increasing body mass index (BMI) in most regions of the world [1]. In recent years, it has been established that bariatric surgery is one of the most effective available treatments for morbid obesity.

The gastric bypass was described by Mason and Ito in 1969, and in 1994, the first laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) was performed [2]. Since then, it has become one of the most performed bariatric operations in the United States. This procedure, involving two anastomosis, is considered technically challenging with a substantial learning curve. In an attempt to make it simpler and safer, the OAGB consisting of a single gastrojejunostomy anastomosis has been described in the United States in 1997.

Currently, OAGB is the third most common bariatric surgery worldwide and a comparable alternative to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and sleeve gastrectomy [3,4,5]. In Israel, it has become the most prevalent surgery accounting for 63% of bariatric procedures performed [6]. This procedure is thought to have a relatively short learning curve for experienced bariatric surgeons and is considered safe, technically simpler than RYGB, with excellent weight loss outcomes [7].

Marginal ulcer (MU) is one of the most significant non-immediate complications of gastric bypass which occurs due to mucosal erosion at the site of the anastomosis [8, 9]. The reported mean incidence rate of MU following RYGB is 4.6%, ranging from 0.6 to 16% [10, 11]. There seems to be concern among bariatric surgeons that OAGB is associated with a relatively higher rate of MU compared with RYGB. Furthermore, ulcers after OAGB are thought to be more refractory to best medical therapy. One possible mechanism is the constant exposure to bile which might cause chemical injury to the mucosa at the site of the gastro-jejunostomy, contributing to ulcer formation [12, 13]. Nevertheless, it seems that this theory is not evidence based and to date a comparison of this sort has not been performed. The aim of this study was to compare the rate of MU between OAGB and RYGB. Secondary outcomes such as ulcer presentation and management were compared as well.

Materials and Methods

Following approval of our institutional review board, a retrospective analysis was performed. All RYGB and OABG procedures performed at our institute between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2020, were included in this study. Exclusion criteria included: non-elective procedure, age < 16 years, non-obesity indication, and malignancy discovered during surgery. There was no upper age limit.

All patients underwent preoperative assessment in our multidisciplinary bariatric clinic and met the previously proposed criteria for the performance of bariatric surgery [14]. A detailed dialog was held with patients regarding the surgical options including laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG), laparoscopic OAGB and laparoscopic RYGB, pros and cons of each procedure, and potential short- and long-term complications. Patients with clinical symptomatic GERD were advised against the performance of a sleeve gastrectomy or a OAGB and were advised in favor of a RYGB. Patients with a co-morbid metabolic syndrome, and especially those with diabetes mellitus type 2 were advised to undergo a RYGB or an OAGB, as these options tend to show a slight improvement in the resolution of comorbidities compared with LSG [15].

Data was extracted from institutional electronic records and included demographic information, BMI, comorbidities, laboratory values, imaging findings, surgical complications, and outcomes. Special attention was given to the patients’ compliance to prophylactic proton pump inhibitors (PPI), treatment, and smoking habits. A smoker was defined by self-report on consistent use of cigarettes in past or present, regardless of the number of cigarettes. Marginal ulcer diagnoses were defined according to patients’ symptoms and evidence of an anastomotic ulcer observed during gastroscopy or surgery. Written or visual documentation of ulcer by gastroscopy performed in outpatient clinics were included as well.

All procedures were performed laparoscopically by two bariatric surgeons using similar technique, compatible with the single anastomosis sleeve-jejunal (SASJ) bypass previously reported [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. OAGB was constructed via a 36 Fr bougie and a single gastro-jejunal anastomosis performed with a 45-mm linear stapler sparing a biliopancreatic limb of 200 cm measured from the ligament of Treitz. Before abdomen closure, an anastomotic leak test was performed with methylene blue, followed by hemostasis, and placement of a JP drain. The drain is routinely left up until discharge.

RYGB was constructed by the creation of a 25–35-mL gastric pouch. Alimentary limbs of 150 cm and biliopancreatic limb of 100 cm were considered standard. The gastrojejunal anastomosis was constructed similarly to the OAGB, utilizing a 45-mm linear stapler to form the gastrojejunal anastomosis, with a hand-sewn common enterotomy. The jejunojejunal anastomosis was formed using a 60-mm stapler, with stapling of the common enterotomy. An anastomotic leak test was performed with methylene blue, followed with placement of a JP drain until discharge.

Our postoperative protocol includes an upper gastrointestinal (UGI) swallow test with Telebrix on the first postoperative day, twice daily monitoring, and a gradual return to solid foods. Prophylactic antiacids are administered postoperatively throughout the admission intravenously (Pantoprazole 40 mg b.i.d). Upon discharge, patients are prescribed prophylactic PPI for 6 months. Our institutional protocol entails oral Esomeprazole 20 mg b.i.d for 3 months, followed by 3 months of Esomeprazole 20 mg q.d.

The first follow-up clinic is scheduled ten days after the operation and then 1, 3, 6, and 12 months afterwards. An annual follow-up is recommended for all patients after the first year. Any hospital admission after surgery was also considered as a follow-up.

The need for informed consent was waived by our institutional review board, the Hadassah Medical Center Helsinki Committee, due to the retrospective nature of the study.

To identify differences between the study groups, univariate analysis was performed using a chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for ordinal or categorical variables. For continuous variables, distribution normality was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and either the Mann–Whitney U test or Student’s T test were used appropriately. Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS (version 26; SPSS, Inc.). A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant for all comparisons.

Data are presented as the mean or median (standard deviation), as appropriate.

Results

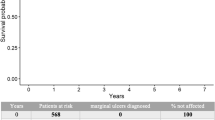

During the study period, a total of 863 operations were performed: 372 (43.1%) patients underwent OAGB, and 491 (56.9%) patients underwent RYGB. Marginal ulcer occurred in 23 (6.2%) OAGB patients and 35 (7.1%) RYGB patients (p = 0.58).

Table 1 presents a comparison of demographics and preoperative characteristics of both groups. Sixty-five percent of the entire cohort were female (64.7% OAGB vs. 66.0% RYGB, p = 0.71). Patients who underwent OAGB were significantly younger compared to the RYGB patients (44.1 ± 11.7 vs 48.8 ± 11.9 years, p < 0.01) and had less comorbidities. Smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, fatty liver, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) were all more frequent in the RYGB group. Significantly more patients in the RYGB group underwent revisional surgeries (24.1% vs. 40.3%, p < 0.01). The majority of revisions in OAGB patients were preformed after a previous sleeve gastrectomy. Most revisions in the RYGB group were after a former adjustable gastric band. The mean follow-up time was 31 ± 32.3 months.

Data regarding patients who developed ulcers and their clinical presentation is summarized in Table 2. Mean time until ulcer diagnosis was shorter in the OAGB group (12 ± 11 vs. 22 ± 17 months, p < 0.01). Epigastric pain was the most common symptom among patients diagnosed with an MU and was present in almost all patients (78% OAGB vs. 88.5% RYGB, p = 0.70). Of patients diagnosed with MU, acute perforation was the presenting symptom in 4/23 (17.4%) patients in the OAGB group and in 4/35 (11.4%) patients in the RYGB group (p = 0.7).

The management of patients diagnosed with MU in each group is summarized in Table 3. All patients were initially treated with high dose PPIs, except one patient who was diagnosed as an out-patient and was lost to follow-up. Endoscopies were performed in all patients diagnosed with an MU. Therapeutic endoscopy with thermal coagulation or adrenaline injections for uncontrolled bleeding was required in 5 OAGB vs. 3 RYGB patients. Seven versus 28 patients in the OAGB and RYGB, respectively, required endoscopic dilatations due to anastomotic stenosis. Hospitalization was required in 74% OAGB vs. 68.5% of RYGB patients (p = 0.77) with a similar mean hospitalization time (10.1 ± 5 vs 6.5 ± 5.03 days, p = 0.41).

Of all patients diagnosed with MU, operative management was necessary in 5 OAGB patients (21.7%) and 6 RYGB patients (17.1%) patients (p = 0.11). In each group, 4 patients were re-operated due to an acute perforation. In the OAGB, 3 MU perforations were spontaneous and were treated with laparoscopic primary repair and omentopexy. The fourth patient suffered from an iatrogenic perforation that occurred during endoscopic dilation due to stenosis from a persistent MU and underwent a laparoscopic revision to RYGB. The fifth patient in the OAGB group was re-operated due to stenosis in the anastomosis site after several insufficient endoscopic dilations and a laparoscopic RYGB was performed.

In the RYGB group, of the 4 patients who were re-operated due to an acute perforation, 3 MU perforations were spontaneous and were treated with laparoscopic primary repair and omentopexy. The fourth patient suffered from an iatrogenic perforation that occurred during an endoscopic dilation due to stenosis from a persistent MU and underwent laparoscopic revision of the gastro-jejunostomy.

The other two patients in the RYGB group underwent a laparoscopic revision of the gastro-jejunostomy due to a persistent symptomatic MU. There were no mortalities in either group.

Discussion

The results of our study demonstrate that the risk of developing a marginal ulcer is similar between patients who underwent OAGB and RYGB.

Other studies support these findings. Robert et al. in their prospective, multicenter, randomized non-inferiority trial, held in nine centers in France, randomized 253 morbidly obese patients to OAGB (n = 129) or RYGB (n = 124), with a follow-up of 2 years [23]. They reported 3 ulcers in the RYGB group and 2 in the OAGB group with an overall ulcer rate of 1.2%. Similarly, Rheinwalt et al. prospectively studied 783 primary procedures with a 3-year follow-up and found 16 ulcers in 355 RYGB patients (4.5%) and 10 ulcers in 428 OAGB (2.3%), p = 0.79 [24]. Although both studies identified somewhat of a decrease in the ulcer rate in OAGB patients, the authors did not discuss the clinical aspect of these ulcers, including their clinical presentation, implications, or management. It should be noted that the relatively low ulcer rate in the abovementioned studies can be attributed to a short follow-up period.

Several studies including a meta-analysis and systematic review report similar findings with equal or lower incidence of MU in OAGB [3, 4, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Despite present data, many surgeons are still concerned that bile reflux may contribute to a higher rate of MU after OAGB [33]. Our cohort strengthens the approach that this concern is not evidence based.

The presenting symptoms of MU in both groups were quite similar. Epigastric pain was the most common symptom occurring in over 78% of the cases, while dysphagia, vomiting, and gastro-intestinal bleeding were all by far less frequent. The only variable we found to differ between the groups was the time from surgery to presentation which was significantly shorter in the OAGB group (12 vs. 22 months, p < 0.01). A possible explanation for the earlier presentation of MU after OAGB was presented by Aviran et al. suggesting that the Billroth II structure of the OAGB entails both sides of the jejunal loop pulling down on the anastomosis, potentially creating greater local tension on the anastomosis, which might cause some degree of ischemia [34]. However, this anatomical explanation should have increased the ulcer rate as well. In our opinion, the earlier time to presentation might be explained by a higher index of suspicion, as clinicians are more aware of MU as a possible complication of OAGB, urging patients to undergo a prompt gastroscopy after presenting with epigastric pain.

Acute presentation with perforation upon admission was documented in 8 patients (0.9%) in our cohort, 4 patients in each group. All patients were operated immediately by an experienced bariatric surgeon with satisfactory outcomes. Abu-Abeid et al. in their retrospective cohort of 1425 OAGB patients described a similar MU perforation rate of 0.7% [35]. All 12 patients in their cohort were treated surgically, 11 of 12 patients underwent omentopexy ± primary repair, and only one patient underwent a laparoscopic conversion to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. In our cohort, all patients who presented with acute spontaneous MU perforation were treated with laparoscopic primary repair and omentopexy. Two patients who presented with an iatrogenic perforation which occurred during endoscopic dilation, underwent laparoscopic revision of the anastomosis, addressing both the stenosis and perforation.

As this rare complication can lead to severe sepsis and death, a high index of suspicion followed by a prompt CT scan is the key to an early diagnosis and optimal treatment [34, 35]. In our opinion, emergent surgery should be performed by experienced bariatric surgeons, as their familiarity with anatomical considerations and MU disease consequences are higher than the average general surgeon.

Our findings demonstrate that the vast majority of patients presenting with symptomatic MU can be managed successfully with conservative treatment, considering hospitalization on a case-by-case basis. Conservative treatment includes a short course of high dose PPI, preferably intravenously, and administration of blood transfusion in cases of symptomatic bleeding. Indolent cases can be resolved with oral PPIs solely. Similar recommendations have been described in the literature regarding both OAGB and RYGB [36, 37].

Smoking, NSAID usage, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and Helicobacter pylori infection have previously proven to be risk factors for developing ulcers in RYGB [8, 38,39,40]. In our study, one patient in each group had a history of considerable NSAID usage prior to ulcer diagnosis which most likely contributed to ulcer formation. Smoking rates among patients who developed ulcers were more than twofolds more prevalent when compared with the original groups (15.3% vs. 39.1% in OAGB, 25.8% vs. 54.2% in RYGB patients). Patients who smoke should be educated regarding the increased risk of developing an MU and counseled for smoking cessation. Further research on specific risk factors in OAGB and the differences between the two procedures is still required.

This study has several limitations. The retrospective nature of the study has its obvious limitations regarding selection bias, data collection, and reporting. Similar to past studies, we choose to omit occult ulcers and focus only on symptomatic ulcers. Underestimation is also possible due to lost to follow-up. A future prospective randomized study, comparing OAGB and RYGB, with an active endoscopy follow-up is warranted to fully understand the extent of this complication in both cohorts and its true clinical relevance.

Despite these limitations, our study presents outcomes of a large cohort (N = 863) comparing two common procedures performed extensively at our institution. The results demonstrate that the risk of developing a marginal ulcer after OAGB is similar to the well-known RYGB. Furthermore, the presentation, management, and outcomes are comparable when treated by an experienced bariatric surgeon. We believe that the risk of MU should not deter surgeons from performing OAGB, and we hope that our findings will serve as valuable guidance for clinicians when counseling bariatric patients before surgery.

References

Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2627–42.

Faria GR. A brief history of bariatric surgery. Porto Biomed J. 2017;2(3):90–2.

Parmar CD, Mahawar KK. One anastomosis (mini) gastric bypass is now an established bariatric procedure: a systematic review of 12,807 Patients. Obes Surg. 2018;28(9):2956–67.

Parikh M, Eisenberg D, Johnson J, et al. American Society for metabolic and bariatric surgery review of the literature on one-anastomosis gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(8):1088–92.

Haddad A, Bashir A, Fobi M, et al. The IFSO worldwide one anastomosis gastric bypass survey: techniques and outcomes? Obes Surg. 2021;31(4):1411–21.

Kaplan U, Romano-Zelekha O, Goitein D, et al. Trends in bariatric surgery: a 5-year analysis of the Israel National Bariatric Surgery Registry. Obes Surg. 2020;30(5):1761–7.

Musella M, Berardi G, Velotti N, et al. Safety and efficacy of OAGB/MGB during the learning curve: setting a benchmark in a bariatric center of excellence. Updates Surg. 2023;75(1):169–74.

Coblijn UK, Lagarde SM, de Castro SM, et al. Symptomatic marginal ulcer disease after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: incidence, risk factors and management. Obes Surg. 2015;25(5):805–11.

Pyke O, Yang J, Cohn T, et al. Marginal ulcer continues to be a major source of morbidity over time following gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(10):3451–6.

Baldwin D, Ali AM, Altieri MS, et al. Marginal ulceration after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass - literature review and management algorithm. Metab Target Organ Damage. 2024;4(1):6.

Salame M, Jawhar N, Belluzzi A, Al-Kordi M, Storm AC, Abu Dayyeh BK, et al. Marginal ulcers after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: etiology, diagnosis, and management. J Clin Med. 2023;12(13).

Bruzzi M, Chevallier JM, Czernichow S. One-anastomosis gastric bypass: why biliary reflux remains controversial? Obes Surg. 2017;27(2):545–7.

Mahawar KK, Reed AN, Graham YNH. Marginal ulcers after one anastomosis (mini) gastric bypass: a survey of surgeons. Clin Obes. 2017;7(3):151–6.

De Luca M, Angrisani L, Himpens J, et al. Indications for surgery for obesity and weight-related diseases: position statements from the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO). Obes Surg. 2016;26(8):1659–96.

Salminen P, Grönroos S, Helmiö M, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss, comorbidities, and reflux at 10 years in adult patients with obesity: the SLEEVEPASS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2022;157(8):656–66. Research Foundation awarded to Turku University Hospital and the Mary and Georg C. Ehrnrooth Foundation during the conduct of the study. Dr Grönroos reported grants from the Orion Research Foundation, the Paulo Foundation, and the Gastroenterological Research Foundation during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported.

Pazouki A, Kermansaravi M. Single anastomosis sleeve-jejunal bypass: a new method of bariatric/metabolic surgery. Obes Surg. 2019;29(11):3769–70.

Salama TMS, Sabry K, Ghamrini YE. Single anastomosis sleeve ileal bypass: new step in the evolution of bariatric surgeries. J Invest Surg. 2017;30(5):291–6.

Mahdy T, Al Wahedi A, Schou C. Efficacy of single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass for type-2 diabetic morbid obese patients: gastric bipartition, a novel metabolic surgery procedure: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg 2016;34:28–34

Mahdy T, Gado W, Alwahidi A, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy, one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB), and single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass in treatment of morbid obesity: a retrospective cohort study. Obes Surg. 2021;31(4):1579–89.

Mahdy T, Emile SH, Alwahedi A, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with long biliopancreatic limb compared to single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass in treatment of morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2021;31(8):3615–22.

Mahdy T, Emile SH, Madyan A, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass for patients with morbid obesity: a multicenter study. Obes Surg. 2020;30(3):837–45.

Sewefy AM, Saleh A. The outcomes of single anastomosis sleeve jejunal bypass as a treatment for morbid obesity (Two-year follow-up). Surg Endosc. 2021;35(10):5698–704.

Robert M, Espalieu P, Pelascini E, et al. Efficacy and safety of one anastomosis gastric bypass versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for obesity (YOMEGA): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10178):1299–309.

Rheinwalt KP, Plamper A, Rückbeil MV, et al. One anastomosis gastric bypass-mini-gastric bypass (OAGB-MGB) versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB)-a mid-term cohort study with 612 Patients. Obes Surg. 2020;30(4):1230–40.

Georgiadou D, Sergentanis TN, Nixon A, et al. Efficacy and safety of laparoscopic mini gastric bypass. A systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(5):984–91.

Wang FG, Yan WM, Yan M, et al. Outcomes of mini vs roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Int J Surg. 2018;56:7–14.

Lee WJ, Almalki OM, Ser KH, et al. Randomized controlled trial of one anastomosis gastric bypass versus Roux-En-Y gastric bypass for obesity: comparison of the YOMEGA and Taiwan studies. Obes Surg. 2019;29(9):3047–53.

Magouliotis DE, Tasiopoulou VS, Tzovaras G. One anastomosis gastric bypass versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity: a meta-analysis. Clin Obes. 2018;8(3):159–69.

Kaplan U, Aboody-Nevo H, Gralnek IM, et al. Early outcomes and mid-term safety of one anastomosis gastric bypass are comparable with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a single center experience. Obes Surg. 2021;31(8):3786–92.

Carbajo MA, Luque-de-León E, Jiménez JM, et al. Laparoscopic one-anastomosis gastric bypass: technique, results, and long-term follow-up in 1200 patients. Obes Surg. 2017;27(5):1153–67.

Mahawar KK, Jennings N, Brown J, et al. “Mini” gastric bypass: systematic review of a controversial procedure. Obes Surg. 2013;23(11):1890–8.

Carandina S, Soprani A, Zulian V, et al. Long-term results of one anastomosis gastric bypass: a single center experience with a minimum follow-up of 10 years. Obes Surg. 2021;31(8):3468–75.

Ferrer-Márquez M, García-Redondo M, Maturana-Ibáñez V, et al. Bile reflux and marginal ulcers after one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB). A narrative review. Cir Esp (English Edition). 2023;101:S69–S75.

Aviran E, Rayman S, Yehuda AB, et al. Marginal ulcer causing delayed anastomotic perforation following one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB). Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2021;17(2):379–83.

Abu-Abeid A, Tome J, Lahat G, Eldar SM, Dayan D. Anastomotic ulcer perforation following one anastomosis gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2022;32(7):2366–72.

Ramos AC, Chevallier JM, Mahawar K, Brown W, Kow L, White KP, et al. IFSO (International Federation for Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders) Consensus Conference Statement on One-Anastomosis Gastric Bypass (OAGB-MGB): results of a modified Delphi study. Obes Surg. 2020;30(5):1625–34.

Lee S, Supparamaniam S, Varghese C, et al. Marginal ulcers following one-anastomosis gastric bypass: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2023;33(9):2884–97.

Rasmussen JJ, Fuller W, Ali MR. Marginal ulceration after laparoscopic gastric bypass: an analysis of predisposing factors in 260 patients. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(7):1090–4.

Azagury DE, Abu Dayyeh BK, Greenwalt IT, Thompson CC. Marginal ulceration after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: characteristics, risk factors, treatment, and outcomes. Endoscopy. 2011;43(11):950–4.

Di Palma A, Liu B, Maeda A, et al. Marginal ulceration following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: risk factors for ulcer development, recurrence and need for revisional surgery. Surg Endosc. 2021;35(5):2347–53.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Amram Kupietzky and Omri Dodi are co-first authors and contributed equally to this work.

Ronit Grinbaum and Ido Mizrahi are co-last authors and contributed equally to this work.

Key Points

• The risk of developing a MU is similar after OAGB and RYGB.

• The prevalence of MU after OAGB vs. RYGB was 6.2% vs. 7.1%, respectively.

• OAGB MU tends to present earlier than MU after RYGB; however, the clinical presentation and management are similar.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kupietzky, A., Dodi, O., Cohen, N. et al. Similar Rates of Symptomatic Marginal Ulcers After One-Anastomosis-Gastric Bypass Compared to Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. OBES SURG 34, 2331–2337 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-024-07298-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-024-07298-y