Abstract

Summary

Bisphosphonates are the most common treatment for osteoporosis but there are concerns regarding its use in CKD. We evaluated the frequency of BSP by eGFR categories among patients with osteoporosis from two healthcare systems. Our results show that 56% of patients were treated, with reduced odds in those with lower eGFR.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is common in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Bisphosphonates (BSP) are the most common treatment but there are concerns regarding its efficacy and toxicity in CKD. We evaluated the frequency of BSP use by level of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in patients with osteoporosis.

Methods

We assessed BSP use in patients with incident osteoporosis from the SCREAM-Cohort, Stockholm-Sweden, and Geisinger Healthcare, PA, USA. Osteoporosis was defined as the first encountered ICD diagnosis, and BSP use was defined as the dispensation or prescription of any BSP from 6 months prior to 3 years after the diagnosis. Multinomial logistic regression was used to account for the competing risk of death.

Results

A total of 15,719 women and 3011 men in SCREAM and 17,325 women and 3568 men in Geisinger with incident osteoporosis were included. Overall, 56% of individuals used BSP in both studies, with a higher proportion in women. After adjustments, the odds of BSP was lower across lower eGFR in SCREAM, ranging from 0.90 (0.81–0.99) for eGFR 75–89 mL/min/1.73m2 to 0.56 (0.46–0.68) for eGFR 30–44 mL/min/1.73m2 in women and from 0.72 (0.54–0.97) for eGFR of 60–74 to 0.42 (0.25–0.70) for eGFR 30–44 mL/min/1.73m2 in men. In Geisinger, odds were lower for eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73m2 in both sexes and the frequency of BSP use dropped over time.

Conclusion

In the two healthcare systems, approximately half of the people diagnosed with osteoporosis received BSP. Practices of prescription in relation to eGFR varied, but those with lower eGFR were less likely to receive BSP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a common condition among people aged more than 50 years, affecting 10.2 million adults in the USA alone in 2010 [1], and associated with increased risk of fractures [2,3,4,5]. Fractures are independently associated with an increased short- and long-term risk of mortality as well as a high number of disability-adjusted life-years [6,7,8]. Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis are important not only for reducing the incidence of fractures but also for reducing fracture-associated morbidity and mortality. Bisphosphonates (BSP) are the first-line treatment most commonly prescribed for osteoporosis.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a frequent comorbid condition among people with osteoporosis and independently associated with the risk of fracture [9,10,11,12,13]. There are concerns regarding the use of BSP in CKD, including the induction of low turnover disease, increased risk of atypical fractures, and increased risk of kidney, gastrointestinal, and other side effects [14, 15]. As such, the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guideline on Chronic Kidney Disease – Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD) recommends BSP use for patients with eGFR > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 with no evidence of CKD-MBD and at high risk of fractures [16]. However, it is not known if these recommendations are being followed in the clinical practice. In addition, in 2010, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a Drug Safety Communication about the risk of atypical fractures with BSP, particularly with prolonged use [17], a warning that has been associated with a change in osteoporosis drug utilization, at least in the patients insured by Medicaid [18].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the frequency of BSP use among patients with osteoporosis across the spectrum of eGFR. For this purpose, we used data from two large healthcare systems: the SCREAM (Stockholm CREAtinine Measurements) Cohort, collecting healthcare practice from the Stockholm region, Sweden, and Geisinger, a health system serving central and northeast PA, USA.

Methods

Study populations

SCREAM is a healthcare extraction of all patients undergoing creatinine testing in Stockholm healthcare between 2006 to 2012, with a cross-link to several national data sources, including the National Population Registry, National Renal Registry, and National Prescribed Drug Registry, among others [19]. Geisinger is a large, integrated healthcare system that serves more than 3 million residents in central and northeast PA, USA. Deidentified patient data from inpatient and outpatient encounters from 2006 up to February 29, 2016, were used in this analysis. The use of data for this study was approved by the Stockholm Ethics Review Board, the Geisinger Medical Center Institutional Review Board, and the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

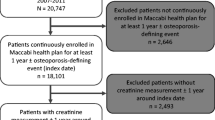

In both healthcare systems, inclusion criteria were the presence of incident osteoporosis defined as the first-encountered ICD code for osteoporosis (Supplementary Table 1) in those aged 18 years or more, along with availability of at least one outpatient serum creatinine up to 1 year prior to osteoporosis diagnosis in SCREAM and 18 months prior to osteoporosis diagnosis in Geisinger. In SCREAM, ICD-10 diagnoses were available for all patients since 1997, while in Geisinger, ICD codes were available from the point of patient entry into the healthcare system. The date of the first diagnosis of osteoporosis defined the baseline. In SCREAM, from 2006 to 2012, 23,274 incident osteoporosis cases were identified. A total of 4544 were excluded due to missing creatinine, renal transplantation, or Paget’s disease, leaving 18,730 individuals for analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). In Geisinger, from 2006 to 2016, 28,274 incident osteoporosis cases were identified. A total of 7381 were excluded due to renal transplantation, Paget’s disease, age < 18 years or missing creatinine, age, sex, and race, leaving 20,893 individuals for analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Outcome and covariate definitions

“BSP use” was ascertained as either prevalent (6 months prior to baseline) or incident use (up to 3 years following the diagnosis of osteoporosis), assessed by electronic prescription (Geisinger) or dispensations (SCREAM, ATC codes provided in Supplementary Table 2) of any class of BSP. Data for individual BSPs was also obtained using the same definitions above. In order to account for the competing risk of mortality, events of death within 3 years after osteoporosis diagnosis (but not after BSP treatment) were also computed. In SCREAM, the date of death was obtained from the Swedish Death register, with complete national coverage and no loss to follow-up. In Geisinger, the date of death is ascertained by linkage to the Social Security Death Index.

We calculated eGFR using outpatient creatinine measurements at baseline and the CKD-EPI equation [20], and participants were classified into 9 categories considering eGFR and dialysis status as follows: dialysis, ≤ 29, 30–44, 45–59, 60–74, 75–89, 90–104, 105–119, and ≥ 120 mL/min/1.73 m2. Comorbid conditions (cardiovascular disease, heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple myeloma, fractures, and prostate, breast, and colon and rectum cancer) were defined by ICD codes (Supplementary Table 1) since 1997 in SCREAM or since patient entry in Geisinger Healthcare up to baseline date. Age, sex, self-reported race, smoking status, and body mass index (BMI) were captured as the closest available information up to 1 year prior to baseline. Race, BMI, and smoking were available only in Geisinger. The Geisinger cohort was also split into two time periods (2006–2011 and 2012–2016), in order to assess potential changes in the pattern of prescription over time. Medication use at baseline defined as prescription or dispensation up to 1 year prior to baseline was ascertained for injectables and oral corticosteroids, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), non-topical hormone replacement therapy (HRT, only in Geisinger), denosumab, calcium, and vitamin D2/D3 (ATC codes used in SCREAM in Supplementary Table 2).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed separately for men and women. We compared baseline characteristics of participants according to baseline eGFR categories. We calculated the frequency of BSP use (for any BSP and for each individual drug) overall and by eGFR categories in the two cohorts. Lastly, we performed unadjusted and adjusted multinomial logistic regression models for the occurrence of BSP use and death, using patients who did not receive BSP as the reference group. We used the GFR category of 90–104 mL/min/1.73 m2 as the reference group as we have previously used as it allows risk to be considered at higher and lower GFR. Higher values of eGFR are prone to overestimation of GFR related to misclassification bias by creatinine-based equations [21, 22]. Analyses were done using the R software (http://www.R-project.org) and Stata MP 14 in SCREAM and Geisinger, respectively.

Results

In Table 1, baseline characteristics by sex are shown in SCREAM and Geisinger. In SCREAM, the mean age was 72 and 66 years in women and men, respectively. A history of fracture at any site was present in 42% of women and in 35% of men, while a history of femoral and lumbar spine fractures was present in 12% in men and women. In Geisinger, the mean age was 70 and 71 years in women and men, respectively. History of fractures was less frequent than in SCREAM: fractures at any site were present in 13% of women and 22% of men, while femoral and lumbar spine fractures were present in 4% of women and 11% of men. Hormone replacement therapy was prescribed in 23% of women in Geisinger at baseline (information not available in SCREAM). Corticosteroid was used by 40% of women and 55% of men in Geisinger and in 31% of women and 37% of men in SCREAM. Baseline features according to eGFR categories in SCREAM and Geisinger are shown in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4. As expected, patients with lower eGFR were older, with higher frequencies of diabetes, hypertension, CVD, and heart failure. In addition, patients in the lower eGFR categories also presented higher rates of history of fractures in both studies.

Table 2 displays the prevalence rates of BSP use overall and according to sex and eGFR categories. The overall prevalence rate was 56% in both SCREAM and Geisinger. Women had a higher rate of BSP use in comparison to men (58% vs. 41% in SCREAM, and 57% vs. 48% in Geisinger, p < 0.001 for both). In SCREAM, rates were lower for those with eGFR < 44 mL/min/1.73 m2 and for those with eGFR > 105 mL/min/1.73 m2 in both sexes. In Geisinger, a similar pattern was observed, with lower rates for those with eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and for those with eGFR > 105 mL/min/1.73 m2 in both sexes. Those not receiving BSP were younger and had higher BMI and less comorbidities (Tables 3 and 4). In both studies, there was a similar distribution of specific BSP agents used (Supplementary Table 5).

In Geisinger, the prevalence rate of BSP use within 3 years of incident osteoporosis was significantly lower in the 2012–2016 cohort in comparison to the 2006–2011 cohort (Supplementary Table 6), with values decreasing from 60 to 47% from 2006 to 2011 to 2012–2016 overall, and from 51 to 42% and 62 to 48% in men and women, respectively (all p values < 0.001). In both time periods, BSP use frequency was lower in those with eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and eGFR > 105 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Figure 1 shows adjusted multinomial logistic regression models on the risk of BSP use (full models available in Supplementary Table 7). In SCREAM, after adjustment for age and other confounders, there were lower odds of BSP use with lower eGFR. In women, the odds of BSP lowered from 0.90 (95%CI 0.81–0.99) for those with eGFR 75–89 mL/min/1.73 m2 to 0.56 (95%CI 0.46–0.68) for those with eGFR of 30–44 mL/min/1.73 m2. In men, a similar pattern was observed, with odds of BSP use of 0.72 (95%CI 0.54–0.97) for those with eGFR 60–74 mL/min/1.73 m2 and of 0.42 (0.25–0.70) for eGFR of 30–44 mL/min/1.73 m2. In Geisinger, the odds of prescription were significantly lower for those with an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (OR 0.54, 95%CI 0.42–0.69 in women and of 0.27, 95%CI 0.13–0.56 in men). In both studies, in women, the odds of BSP use was also lower for eGFR categories > 105 mL/min/1.73 m2 compared to those with 90–104 mL/min/1.73 m2. In Geisinger, results were consistent even after repeating the multivariable model without including BMI and smoking as covariates, variables with missing data.

Adjusted OR of BSP use among osteoporosis patients in SCREAM and Geisinger by eGFR categories. Footnote: Bars represent adjusted odds ratio of BSP use (using no use of BSP as the reference group) from multinomial logistic regression model after adjustment for age, comorbidities, and drugs at baseline in SCREAM (A and B) and same plus race, BMI, and smoking in Geisinger (C and D). Whiskers represent 95%CI of the estimate. Reference group was eGFR category 90–104 mL/min/1.73 m2. OR, odds ratio; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration ratio

In addition to eGFR, in SCREAM, age, history of fractures at any site, breast cancer, hypertension (women), and baseline dispensation of corticosteroids (women only) and calcium were positively associated with the odds of BSP use, whereas baseline dispensation of SERMs and denosumab were negatively associated with the odds of BSP use. In Geisinger, age, current smoking (women), RA, calcium, vitamin D2/D3 showed positive associations, whereas time-period (lower odds for the 2012–2016 cohort in relation to the 2006–2011 cohort), black race, BMI, and baseline denosumab and SERMs were inversely related to the odds of BSP use (Table 5).

Discussion

In the present analysis, we aimed to evaluate the frequency of BSP use, according to eGFR categories among patients with osteoporosis from two large healthcare systems. The analysis showed that BSP was used by approximately half of the patients, and patients with lower eGFR were less likely to receive BSP. There are implications of these findings for the care of osteoporosis in the general population and for those with CKD.

Our findings suggest there may be sub-optimal treatment of osteoporosis in the general population. In both systems, BSP was prescribed only to approximately half of the patients, with a greater proportion of women being assigned to treatment in comparison to men. In SCREAM, regardless of a higher percentage of people reporting previous history of fractures, similar rates of BSP use were observed and were seen in the two studies. In both systems, the frequency of calcium and vitamin D use (ranging from 33 to 62% for calcium and from 42 to 61% for vitamin D in women and men from the 2 cohorts) was not as high as expected, considering that these are recommended maintenance drugs that should be co-administered with other osteoporosis treatments. These findings are consistent with prior literature. A study of older women from Gothenburg, Sweden, showed that only 22% of those eligible for anti-reabsortive treatment were treated and similar findings have been reported in other European countries [23,24,25]. Previous studies on populations seen in specialized clinics in Geisinger showed a higher rate of treatment in comparison to our results, but these differences may be related to different practices between specialized versus primary care [26, 27].

In our analysis, factors associated with lower odds of prescription of BSP in the two studies were eGFR category, age, hypertension, and baseline drugs. In addition, in SCREAM, history of fracture at any site and breast cancer were positively associated with BSP use, whereas in Geisinger, race, BMI, current smoking, and rheumatoid arthritis were related to BSP prescription. However, we note that our data was extracted from administrative records, and we lacked information on some key variables related to osteoporosis treatment, such as DEXA, alcoholism, and family history of fractures, likely to drive the clinical decision about treatment. The decline in use that we observed in Geisinger over time is also consistent with other studies that have reported a trend to decreased use of BSP for the treatment of osteoporosis in the USA [18]. In this study, the authors suggest that the decline reported may be related to the release by the FDA of a drug safety communication in 2010 warning about increased risk of atypical fractures with BSP, particularly with prolonged use [17, 18]. In our study, however, we could not ascertain reasons for the observed difference in BSP prescription rate between 2006 and 2011 and 2012 and2016.

Treatment of osteoporosis in the CKD population is complex. First, bone disease in patients with CKD may reflect not only osteoporosis but also other CKD-related bone manifestations, such as high turnover disease, low turnover disease and osteomalacia [28,29,30]. The diagnosis of these conditions impacts treatment. For example, BSPs can be harmful in low turnover disease and osteomalacia by aggravating the already decreased bone formation rate. However, since no serum or urinary biomarker has an accurate performance, a bone biopsy is still required to distinguish among these conditions, although not widely performed [16, 31]. Second, there are few studies evaluating the efficacy of BSPs in the CKD population. The recommendations for BSP use are based on post hoc analysis of large randomized clinical trials restricted to those individuals with moderate reductions of eGFR [32, 33]. The KDIGO guidelines attempted to balance these issues and recommended BPS in patients with no or moderate declines in GFR and without biochemical evidence of CKD-MBD and who are at increased risk for fractures [16].

In SCREAM, the lower use of BSP in participants with eGFR from 30 to 89 mL/min/1.73 m2 might reflect ongoing concerns with use of BSP in patients with CKD regardless of the guidelines, or that these people were not at high risk for fractures and clinicians are appropriately deciding to hold off therapy. SCREAM presented a higher rate of history of fractures in comparison to Geisinger. Previous studies have shown higher age-standardized fracture incidence in Sweden in comparison to the USA, but in our study, we could not evaluate if the difference observed was simply related to different coding practices between the two healthcare systems [34, 35]. We did not have PTH levels and therefore could not identify participants in whom it was appropriate to hold BSP, nor did we have sufficient information to compute risk of fractures. However, a prior study shows that elevated PTH is not common in these eGFR categories [36].

KDIGO recommends that BSP should not generally be used for eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. It is therefore appropriate that we observe lower use in this eGFR category in both studies. Conversely, a sizeable proportion of participants still had prescriptions even at this eGFR category. This might indicate that clinicians are not attuned to the recommendations by KDIGO and might represent a potential for quality improvement.

In both Geisinger and SCREAM, women, but not men, with eGFR > 104 mL/min/1.73 m2 had a lower rate of BSP use, even after adjustments. These women were younger and also presented an increased risk of death in comparison to the reference group, suggesting that the decreased use of BSP may be related to conditions of illnesses that were not identified in this analysis. eGFRcr at this level might be more reflective of low muscle mass rather than high GFR. As such, higher eGFR values may be related to reduced muscle mass secondary to chronic illness, increasing therefore the likelihood of misclassification bias by eGFR in these people. It is interesting that we did not find this association in men. Men have higher serum creatinine values than women and this might indicate that clinicians are not using eGFR values to dose medications.

Our study strengths were a large sample of people with incident osteoporosis, the use of two health systems from different countries, and the adjustment for the competing risk of death in both, an issue especially relevant given the high mortality rate of CKD. Our study presents also several limitations. First, data is derived from EHR data and we did not perform internal validation for the osteoporosis coding, a fact that can lead to some degree of ascertainment bias and misclassification. This also limited our ability to understand factors associated with BSP prescription. Second, although we did compute use at baseline, we did not compute the incidence of other first-line treatments for osteoporosis, which may occur in lieu of BSP. However, denosumab, teriparatide, raloxifene, and HRT are either more expensive drugs not commonly prescribed or are considered by many as second-line therapy in comparison to BSPs. Third, there may be some underestimation in the usage of BSP: in Geisinger, we could not account for BSP prescribed from other providers, and in SCREAM, intravenous BSPs administered during hospitalizations may not appear as dispensation. In addition, calcium and vitamin D ascertainment may be limited by partial assessment of over-the-counter use, particularly in Geisinger. Fourth, we did not have data on PTH, vitamin D, and DEXA, nor could compute the risk of fractures using validated scores such as FRAX and others [37, 38]. We also could not ascertain CKD and albuminuria as recommended by guidelines and used eGFR alone instead. Lastly, we limited our analysis to 3 years of follow-up so our results do not take into account BSP being prescribed after this period.

In conclusion, our study shows that approximately half of the people diagnosed with osteoporosis received BSP treatment in two large health systems. Practices of BSP prescription in relation to eGFR varied between the two studies, but persons with lower eGFR were less likely to receive BSP treatment. While it is true that BSP use in CKD should be considered carefully, undertreatment of osteoporosis increases the risk for fractures and their associated risk for morbidity and mortality. Studies focusing on specific concerns regarding BSP use in osteoporosis, such as duration of treatment, head-to-head comparison to other first-line treatment options, and efficacy and safety in the CKD population are needed.

References

Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, Curtis JR, Delzell ES, Randall S, Dawson-Hughes B (2014) The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res 29(11):2520–2526. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2269

Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel H (1996) Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ 312(7041):1254–1259. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7041.1254

Cummings SR, Black DM, Nevitt MC, Browner W, Cauley J, Ensrud K, Genant HK, Palermo L, Scott J, Vogt TM (1993) Bone density at various sites for prediction of hip fractures. The study of osteoporotic fractures research group. Lancet 341(8837):72–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(93)92555-8

Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S, Lindsay R (2014) Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 25(10):2359–2381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2

Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergard M, Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J, McCloskey EV, Jonsson B, Kanis JA (2013) Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos 8:136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-013-0136-1

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2006) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 17(12):1726–1733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4

Haentjens P, Magaziner J, Colon-Emeric CS, Vanderschueren D, Milisen K, Velkeniers B, Boonen S (2010) Meta-analysis: excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann Intern Med 152(6):380–390. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-152-6-201003160-00008

Katsoulis M, Benetou V, Karapetyan T, Feskanich D, Grodstein F, Pettersson-Kymmer U, Eriksson S, Wilsgaard T, Jorgensen L, Ahmed LA, Schottker B, Brenner H, Bellavia A, Wolk A, Kubinova R, Stegeman B, Bobak M, Boffetta P, Trichopoulou A (2017) Excess mortality after hip fracture in elderly persons from Europe and the USA: the CHANCES project. J Intern Med 281(3):300–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12586

Klawansky S, Komaroff E, Cavanaugh PF Jr, Mitchell DY, Gordon MJ, Connelly JE, Ross SD (2003) Relationship between age, renal function and bone mineral density in the US population. Osteoporos Int 14(7):570–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-003-1435-y

Alem AM, Sherrard DJ, Gillen DL, Weiss NS, Beresford SA, Heckbert SR, Wong C, Stehman-Breen C (2000) Increased risk of hip fracture among patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 58(1):396–399. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00178.x

Fried LF, Biggs ML, Shlipak MG, Seliger S, Kestenbaum B, Stehman-Breen C, Sarnak M, Siscovick D, Harris T, Cauley J, Newman AB, Robbins J (2007) Association of kidney function with incident hip fracture in older adults. J Am Soc Nephrol 18(1):282–286. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2006050546

Ensrud KE, Lui LY, Taylor BC, Ishani A, Shlipak MG, Stone KL, Cauley JA, Jamal SA, Antoniucci DM, Cummings SR (2007) Renal function and risk of hip and vertebral fractures in older women. Arch Intern Med 167(2):133–139. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.2.133

Runesson B, Trevisan M, Iseri K, Qureshi AR, Lindholm B, Barany P, Elinder CG, Carrero JJ (2019) Fractures and their sequelae in non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease: the Stockholm CREAtinine measurements project. Nephrol Dial Transplant. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfz142

Ott SM (2015) Pharmacology of bisphosphonates in patients with chronic kidney disease. Semin Dial 28(4):363–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/sdi.12388

Miller PD (2007) Is there a role for bisphosphonates in chronic kidney disease? Semin Dial 20(3):186–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00271.x

Ketteler M, Block GA, Evenepoel P, Fukagawa M, Herzog CA, McCann L, Moe SM, Shroff R, Tonelli MA, Toussaint ND, Vervloet MG, Leonard MB (2017) Executive summary of the 2017 KDIGO chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD) guideline update: what’s changed and why it matters. Kidney Int 92(1):26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2017.04.006

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Safety update for osteoporosis drugs, bisphosphonates, and atypical fractures.

Balkhi B, Seoane-Vazquez E, Rodriguez-Monguio R (2018) Changes in the utilization of osteoporosis drugs after the 2010 FDA bisphosphonate drug safety communication. Saudi Pharm J 26(2):238–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2017.12.005

Runesson B, Gasparini A, Qureshi AR, Norin O, Evans M, Barany P, Wettermark B, Elinder CG, Carrero JJ (2016) The Stockholm CREAtinine Measurements (SCREAM) project: protocol overview and regional representativeness. Clin Kidney J 9(1):119–127. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfv117

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J (2009) A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150(9):604–612. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006

Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, Gansevoort RT (2010) Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet 375(9731):2073–2081. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60674-5

Gansevoort RT, Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J (2011) Lower estimated GFR and higher albuminuria are associated with adverse kidney outcomes. A collaborative meta-analysis of general and high-risk population cohorts. Kidney Int 80(1):93–104. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2010.531

Lorentzon M, Nilsson AG, Johansson H, Kanis JA, Mellstrom D, Sundh D (2019) Extensive undertreatment of osteoporosis in older Swedish women. Osteoporos Int 30(6):1297–1305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-019-04872-4

Haussler B, Gothe H, Gol D, Glaeske G, Pientka L, Felsenberg D (2007) Epidemiology, treatment and costs of osteoporosis in Germany--the BoneEVA Study. Osteoporos Int 18(1):77–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0206-y

Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L (2005) Osteoporosis is markedly underdiagnosed: a nationwide study from Denmark. Osteoporos Int 16(2):134–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-004-1680-8

Dunn P, Webb D, Olenginski TP (2018) Geisinger high-risk osteoporosis clinic (HiROC): 2013-2015 FLS performance analysis. Osteoporos Int 29(2):451–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-4270-2

Olenginski TP, Antohe JL, Sunderlin E, Harrington TM (2012) Appraising osteoporosis care gaps. Rheumatol Int 32(11):3619–3624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-011-2203-5

Ott SM (2017) Renal osteodystrophy-time for common nomenclature. Curr Osteoporos Rep 15(3):187–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-017-0367-y

Graciolli FG, Neves KR, Barreto F, Barreto DV, Dos Reis LM, Canziani ME, Sabbagh Y, Carvalho AB, Jorgetti V, Elias RM, Schiavi S, Moyses RMA (2017) The complexity of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder across stages of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 91(6):1436–1446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2016.12.029

Bover J, Bailone L, Lopez-Baez V, Benito S, Ciceri P, Galassi A, Cozzolino M (2017) Osteoporosis, bone mineral density and CKD-MBD: treatment considerations. J Nephrol 30(5):677–687. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-017-0404-z

Steller Wagner Martins C, Jorgetti V, Moyses RMA (2018) Time to rethink the use of bone biopsy to prevent fractures in patients with chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 27(4):243–250. https://doi.org/10.1097/mnh.0000000000000418

Miller PD, Roux C, Boonen S, Barton IP, Dunlap LE, Burgio DE (2005) Safety and efficacy of risedronate in patients with age-related reduced renal function as estimated by the Cockcroft and Gault method: a pooled analysis of nine clinical trials. J Bone Miner Res 20(12):2105–2115. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.050817

Jamal SA, Bauer DC, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Hochberg M, Ishani A, Cummings SR (2007) Alendronate treatment in women with normal to severely impaired renal function: an analysis of the fracture intervention trial. J Bone Miner Res 22(4):503–508. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.070112

Kanis JA, Oden A, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Wahl DA, Cooper C (2012) A systematic review of hip fracture incidence and probability of fracture worldwide. Osteoporos Int 23(9):2239–2256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-1964-3

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Sembo I, Redlund-Johnell I, Dawson A, De Laet C, Jonsson B (2000) Long-term risk of osteoporotic fracture in Malmo. Osteoporos Int 11(8):669–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980070064

Inker LA, Grams ME, Levey AS, Coresh J, Cirillo M, Collins JF, Gansevoort RT, Gutierrez OM, Hamano T, Heine GH, Ishikawa S, Jee SH, Kronenberg F, Landray MJ, Miura K, Nadkarni GN, Peralta CA, Rothenbacher D, Schaeffner E, Sedaghat S, Shlipak MG, Zhang L, van Zuilen AD, Hallan SI, Kovesdy CP, Woodward M, Levin A (2019) Relationship of estimated GFR and albuminuria to concurrent laboratory abnormalities: an individual participant data meta-analysis in a global consortium. Am J Kidney Dis 73(2):206–217. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.08.013

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E (2008) FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int 19(4):385–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0543-5

Whitlock RH, Leslie WD, Shaw J, Rigatto C, Thorlacius L, Komenda P, Collister D, Kanis JA, Tangri N (2019) The fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX(R)) predicts fracture risk in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 95(2):447–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2018.09.022

Funding

This study was partly supported by the R01 Grant 5R01DK115534-02 (MEG and LAI) and by the Swedish Research Council grant 2019-01059 (JJC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Evans reports funding to Karolinska Institutet from Astra Zeneca and Astellas outside this work and payment for lectures (Astellas, Vifor Pharma) and advisory board (Astra Zeneca, Astellas). Dr. Grams reports funding from the National Kidney Foundation and the NIH. Dr. Inker reports funding to Tufts Medical Center for research and contracts with the NIH, NKF, Dialysis Inc., Retrophin, Omeros, and Reata Pharmaceuticals. She has consulting agreements with Tricida. Dr. Carrero reports funding to Karolinska Institutet for research from AstraZeneca, Viforpharma, Astellas, and MSD outside the submitted work. He has performed consultation for Fresenius and Baxter. All the other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 230 kb).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Titan, S.M., Laureati, P., Sang, Y. et al. Bisphosphonate utilization across the spectrum of eGFR. Arch Osteoporos 15, 69 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-020-0702-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-020-0702-2