Abstract

Objective

The aim of the current study was to perform the translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Underactive Bladder Questionnaire (UAB-q).

Methods

The study design included the Portuguese translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the UAB-q in 90 patients from a urology outpatient clinic following international methodology. The psychometric properties tested were the validity, reliability, internal consistency and stability of the instrument.

Results

The content validity index at the item (I-CVI) and scale level (S-CVI) were above 0.80 and did not require changes. Regarding the reliability analysis, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79. The internal consistency and the base time stability (test–retest) had excellent indexes; all were above 0.90.

Conclusions

These results indicate that the UAB-q is a valid, reproducible and reliable instrument for screening underactive bladders and is a potentially useful tool to guide health actions and improve the care of underactive patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) increase significantly with age and include overactive bladder symptoms on a larger scale. However, there is also incomplete bladder emptying and impaired detrusor contractility that manifests as underactive bladder symptoms. Detrusor muscle contractility is inversely proportional to age, but the pathophysiology may be multifactorial; it is present in both men and women and includes several comorbidities [1].

There are several age-related changes in bladder functionality, which may have a neurogenic, myogenic or ischaemic origin. Detrusor underactivity (DU) has been defined urodynamically, and the term “underactive bladder” refers to a clinical syndrome that includes signs and symptoms of DU such as urinary incontinence, loss of bladder emptying sensation, and hesitancy, which can cause physical discomfort and social restrictions [1].

The standard diagnostic test is still the urodynamic study, which analyses bladder pressure and flow. However, urodynamic evaluation does not identify all the signs of detrusor underactivity, and it is not easily accessible. In addition to being invasive, it requires interpretation by qualified professionals, which can introduce subjectivity; furthermore, it requires more rigorous parameters, particularly for women [2, 3].

As a tool to support health diagnoses, screening instruments emerge to assist in early disease identification, with the aim of standardizing, classifying and organizing symptomatological parameters [4]. Screening evaluations allow the determination of whether the patient has symptoms of an underactive bladder, which enables early and appropriate referral. In view of the population’s ageing in the coming decades and the associated morbidities, LUTS and its repercussions for the population’s quality of life have been highlighted. Recently, an underactive bladder symptoms score called the Underactive Bladder Questionnaire (UAB-q) was developed by the Underactive Bladder Foundation. It has already been used in epidemiological studies, but it is not accessible for populations that are not native English speakers [2, 5]. In recent years, health measurement instruments have been widely used to obtain outcomes objectively on a global scale, including in international multi-centre studies designed to compare data among different populations and validate the instruments’ psychometric properties. However, cross-cultural research has specific methodological problems, most of which are related to translation quality and the comparability of results among different cultural and ethnic groups. A literal translation of an instrument is not adequate; it is also important that the instrument be culturally relevant and comprehensible\while maintaining the meaning and intent of the original terms [6]. The aim of this study was to perform translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Underactive Bladder Questionnaire (UAB-q).

Method

The instrument

The UAB-q instrument is an underactive bladder symptom score developed by the Underactive Bladder Foundation. It contains two identification questions and six issues specific to detrusor underactivity symptoms. The eight items of the instrument are as follows: (1) sex; (2) age; (3) history of needing a catheter to empty the bladder; (4) in the prior week, the number of times the respondent had an urge to urinate, but could not; (5) number of times of nocturia; (6) number of times the respondent has needed to urinate again right after previous urination; (7) number of times the respondent has needed to force the bladder to empty; and (8) sensation that the bladder was not emptied.

Items 3 to 8 are scored from 0 to 3 according to symptom intensity, in ascending order. If the sum of the UAB item scores is 5 or greater, the patient may have an underactive bladder.

Study design and participants

The current study is a methodological study, the purpose of which is to validate and evaluate research methods and tools [7]. For the translation and cross-cultural adaptation, three translators and six specialists participated in this study.

The validation step included subjects > 18 years of age who were able to complete the questionnaire. Subjects with a neurological condition or cognitive/mental deficiency and non-Portuguese native speakers were excluded.

The collected data included a short sociodemographic and clinical interview questionnaire and the application of the Portuguese version of the UAB-q to a sample of 120 symptomatic and asymptomatic patients from an outpatient urology clinic. Sample size was calculated based on a power > 80% for detecting an effect size of ≥ 0.50. The sample for the determination of inter- and intra-observer reliability comprised volunteers who agreed to return to the outpatient clinic.

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (CAEE: 56604316.0.0000.5192), and all participants signed informed consent.

Translation and transcultural adaptation

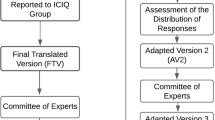

The translation and cross-cultural adaptation process followed international methodology [8]. For the first stage, two independent translators, a forensic trader and a university teacher, performed the translation to Portuguese (T1 and T2). To compile the translations, the researchers and translators judged the T1 and T2 items and generated a unique version (S1). Later, the S1 version was compared to the original by another independent translator (T3). However, before the instrument was administered to patients, it was necessary to perform a cross-cultural adaptation. Therefore, a focus group of specialists in urology and stomatotherapy led to the creation of a new version of the questionnaire (V1). This version was administered to three focus groups of five patients each as described for Hutz et al. [9] A Likert scale was used for the analysis of the patients’ understanding: 0—I did not understand anything; 1—I understood only a little; 2—I understood more or less; 3—I understood almost everything, but I had some doubts; 4—I understood almost everything; 5—I understood perfectly and I have no doubts. After that, the V1 version was back-translated by two independent native English speakers (R1 and R2). These versions were synthesized following the same methodology to generate a unique version (S2). The S2 version was compared with the original questionnaire by a third independent translator, which generated the final version of the questionnaire in the Portuguese language.

Validation process

The content validation step was performed with a convenience sample of six specialists in urology (doctors and nurses), as described by Lynn et al. [10]. The inclusion criteria for the specialists were based on clinical experience and scientific output, as recommended by Teles et al. [11].

For the content validation of the UABq, the content validity index by item (I-CVI) and scale (S-CVI) were applied. The I-ICVI corresponds to the sum of agreement of the items that were marked as 3 or 4 by the specialists divided by the total number of answers. The S-CVI corresponds to the division of the I-IVC by the total number of items [12]. The scores were interpreted according to the following pattern: I-IVC ≥ 0.80 was considered excellent, and I-IVC ranging from 0.60 to 0.79 were considered good. Results should be excluded if scores are equal to or below 0.59 [7, 13].

After content validation, the instrument was applied by two independent examiners with different experience levels to a sample of patients collected from the urology outpatient clinic. The sample size was determined by the following equation: (N = 10 × K or N = 10 × 8 = 80), where N corresponds to the minimum sample size and K represents the number of manifest variables analysed (items of the instrument) [14]. An additional 20% was added to this value due to the possibility of losses, for a total of 96 patients.

A probabilistic sub-sample of 60 patients was selected for a second evaluation with a 2-week interval from baseline for the analysis of test–retest reliability. Internal consistency was analysed using the Cronbach alpha coefficient. For the instrument to be considered reliable, in this study, a Cronbach’s alpha ≥ 0.70 was required [14, 15]. For this calculation, items 1 (gender), 2 (age) and 3 (unable to urinate and needing a probe to empty the bladder) were not included because items 1 and 2 corresponded to the population characterization items and item 3 was a dichotomous variable, unlike the other UAB-q items.

The kappa statistic (K) was used to analyse the inter- and intra-observer agreement to verify the consistency of the UAB-q, with values > 0.8 considered almost perfect, 0.6–0.8 considered substantial agreement, 0.4–0.6 considered moderate agreement, 0.2–0.4 considered regular agreement, and 0.0–0.2 considered weak agreement [12]. For the sensitivity analysis, the linear weighted kappa (KWL) was calculated.

Results

It was necessary to change some expressions for the adaptation, although the professionals and patients comprehended 100% of the items, classifying them as 4 or 5 on the Likert scale. The modified terms in each step are shown in Table 1.

Only minor aspects were changed after the first synthesis of T1/T2 (S1) to improve the comprehension of the instrument. In questions 2 to 5, the expression “what frequency” was changed to “how many times”; in question 3, the expression “typical night” was changed to “night”, and in question 5, the expression “to exert pressure” was changed to “force”. The specialists who performed the validation of the UABq were aged 30 to 39 years, and their Teles score [11] was greater than 15. For the content validity test, the UAB-q was evaluated according to the appropriate nomenclature, clarity, objectivity, relevance and applicability of the items; items were accepted if the proposed domain was pertinent. Both indexes (I-CVI and S-CVI) achieved values greater than 0.80.

There was a loss of 6.25% of the estimated sample size for further stages, resulting in a final sample of 90 participants with a mean age of 65.4 years comprising 53 women and 37 men with symptoms of lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTS).

In the reliability analysis, the Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.79, indicating that the UAB-q Brazilian version showed good reliability. Values are presented as the mean and standard deviation for the individual items, adjusted by item-total correlation and internal consistency. The means and the internal consistency items detected were homogeneous, and all items had scores above 0.70 after correction (Table 2).

The unweighted and weighted kappa values for inter- and intra-observer agreement for each item of the instrument are presented in Table 3. There was a perfect agreement of all items.

Table 4 presents the kappa and weighted kappa statistics for test–retest validity. All items were stable. There was no difference between the unweighted and weighted values.

The criterion validation results were withdrawn from the study because they were not statistically significant and did not allow comparisons and inferences [16].

Discussion

The burden of UAB will increase with the ageing of the population throughout the world. The UAB-Q may be useful for both identifying detrusor underactivity and confirming the efficacy of the patient’s treatment [2, 5].

Cross-cultural adaptation is the initial stage of instrument validation. It is important to verify whether the concepts established in the original instrument were transferrable to the culture of the target population and could be understood in the same way that it is understood by members of the instrument’s original culture. Strategies for analysing cross-cultural adaptation according to ITC guidelines were followed [9, 17]. It was possible to verify the equivalence between the original instrument and the Portuguese version, which ensured the denotative permanence of the words of the instrument. If the terms in both the original and translated versions have the same meaning, the versions have parity [18, 19].

It was essential to use synonyms for some terms, such as those used in items 2 to 5; in such cases, it is important to not modify the intention of the questions and necessary to adhere to the same latent traits that are found in the original instrument. Cultural adaptation involves ensuring the verbal understanding of specialists and patients through focus groups, as established by Hutz et al. [9] and by the strategy of Herdman et al. [19].

Establishing content validity is a fundamental step in the adaptation of new instruments because it verifies the association between abstract concepts with observable and measurable indicators to determine the extent to which the items of the evaluated instrument represent the relevant construct [19, 20]. The specialists’ evaluations showed that the UAB-q had relevant and valid content, and its construct validation (risk of detrusor hypoactivity) was confirmed by its excellent IVC score [7, 21]. The UAB-q was also demonstrated to be a reliable and stable instrument, as demonstrated by its excellent internal consistency and test–retest consistency. [12] The weaknesses of this study are the lack of a gold standard for the diagnosis of DU, which did not allow for comparisons and inferences with which to perform criterion validation [22,23,24].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Portuguese version of the UAB-q was shown to be a valid, reproducible and reliable instrument for underactive bladder screening. The Portuguese version of the UAB-q may be a useful tool to help diagnose, guide health actions and improve the care and welfare of patients with underactive bladder.

References

Kullmann FA, Birder LA, Andersson K-E (2015) Translational research and functional changes in voiding function in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med 31(4):535–548. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0749069015000518. Accessed 5 May 2018

Valente S, DuBeau C, Chancellor D, Okonski J, Vereecke A, Doo F et al (2014) Epidemiology and demographics of the underactive bladder: a cross-sectional survey. Int Urol Nephrol 46(1):7–10

Andersson KE (2014) Bladder underactivity. Eur Urol 65(2):399–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.005

Bolsoni LM, Zuardi AW (2015) Psychometric studies of brief screening tools for multiple mental disorders. J Bras Psiquiatr 64(1):63–69

Chuang YC, Plata M, Lamb LE, Chancellor MB (2015) Underactive bladder in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med 31(4):523–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2015.06.002

Sperber AD (2004) Translation and validation of study instruments for cross-cultural research. Gastroenterology 126(1):124–128

Polit DF, Beck CT (2011) Fundamentals of nursing research: evaluation of evidence for nursing practice, 7th edn. ArtMed, Porto Alegre

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB (2000) Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25(24):3186–3191. http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00007632-200012150-00014. Accessed 5 May 2018

Pires JG (2017) Temas fundamentais em Avaliação Psicológica II. Rev Avaliação Psicológica 16(2):249–251. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1677-04712017000200017&lng=pt&nrm=iso&tlng=pt. Accessed 5 May 2018

Lynn Mary R (1986) Determination and Quantificatiom of Conten Validity. Nurs Res 35(6):382–386

Teles LMR, de Oliveira AS, Campos FC, Lima TM, da Costa CC, de Gomes LFS et al (2014) Development and validating an educational booklet for childbirth companions. Rev da Esc Enferm 48(6):977–984

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 33(1):159–174

International Test Commission (2017) The ITC Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests (Second edition). http://www.intestcom.org/

Field A (2011) Discovering statistics using SPSS [electronic resource]. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/463d/c5de03c98e360b97d01dcac7a71a9a439dcc.pdf. Accessed 5 May 2018

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH (1994) Psychometric theory, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Abrams P (1999) Bladder outlet obstruction index, bladder contractility index and bladder voiding efficiency: three simple indices to define bladder voiding function. BJU Int 84(1):14–15

Conti MA, Jardim AP, Hearst N, Cordás TA, Tavares H, de Abreu CN (2012) Evaluation of the semantic equivalence and internal consistency of a Portuguese version of the Internet Addiction Test (IAT). Rev Psiquiatr Clin 39(3):106–110

Grichnik VD, Grichnik VD (2006) Die opportunity Map der internatio- nalen Entrepreneurshipforschung: zum Kern des interdisziplinären Forschungsprogramms. Entrepreneur 49:1303–1333

Herdman M, Fox-Rushby J, Badia X (1998) A model of equivalence in the cultural adaptation of HRQoL instruments: the universalist approach. Qual Life Res 7:323–335

Cunha NDB (2014) Validity Study of the metatextual awareness evaluation questionnaire. Psychol Theory Pract 16(1):141–154

Chapman J (2012) 30-Level timber building concept based on crosslaminated timber construction. Struct Eng 90(8):36–40

Abarbanel J, Marcus EL (2007) Impaired detrusor contractility in community-dwelling elderly presenting with lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology 69(3):436–440

Li X, Liao LM, Chen GQ, Wang ZX, Lu TJ, Deng H (2018) Clinical and urodynamic characteristics of underactive bladder. Med (United States) 97(3):1–4

Jeong SJ, Kim HJ, Lee YJ, Lee JK, Lee BK, Choo YM et al (2012) Prevalence and clinical features of detrusor underactivity among elderly with lower urinary tract symptoms: a comparison between men and women. Korean J Urol 53(5):342–348

Acknowledgements

We would like to show our gratitude to The Underactive Bladder Foundation for support and permission to perform the study.

Funding

This study had no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author Marilia Perrelli Valença declares that she has no conflict of interest. Author Jabiael Carneiro da silva Filho declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author Isabel Cristina Ramos Vieira Santos declares that she has no conflict of interest. Author Adriano Almeida Calado declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author David D Chancellor declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author Michael B Chancellor declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author Geraldo de Aguiar Cavalcanti declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Ethics Committee (CAEE: 56604316.0.0000.5192) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Valença, M.P., da Silva Filho, J.C., Santos, I.C.R. et al. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the underactive bladder questionnaire to portuguese. Int Urol Nephrol 51, 1329–1334 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-019-02176-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-019-02176-4