Abstract

Using data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, the purpose of this study is twofold. First, the study identifies coping strategies used by older adults. Second, the study examines the impact of older adults’ chosen coping strategies on mortality reduction. The study focuses specifically on differences in the use of religious and secular coping strategies among this population. The findings suggest that although coping strategies differ between those who self-classify as religious and those who self-classify as nonreligious, for both groups social approaches to coping (e.g., attending church and volunteering) are more likely than individual approaches (e.g., praying or active/passive coping) to reduce the risk of mortality. The most efficacious coping strategies, however, are those matched to characteristics of the individual.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Stress processes are inherently intertwined with aging, and there are some stressors that are naturally more common with increases in age than others. Indeed, given the different life transitions generally associated with older adulthood (e.g., retirement, death of a spouse/partner, role loss, loss of muscle mass and strength, the onset of illness, physical impairments and disabilities, visual, auditory, and cognitive impairments, loneliness and isolation (Baumgartner et al. 1999; Bossé et al. 1991; Elwell and Maltbie-Crannell 1981; Hawkley and Cacioppo 2007), stress-inducing experiences often increase considerably in later life; and, stress, when improperly regulated has been shown to increase mortality risk especially among older adult populations (e.g. Aldwin et al. 2011; Krause 1998).

It is no surprise, then, that a number of scholars have sought to understand how older adults cope with stressful life situations (e.g. Kraaij et al. 2002; Moos et al. 2006); and, research in this area has identified myriad coping strategies that older adults tend to rely on in their attempts to deal with stress (for an overview and critique see Skinner et al. 2003). In general, much of this research has focused on the multidimensional nature of coping as a construct (Pearlin and Schooler 1978; Skinner et al. 2003)—emphasizing that coping is not a one size fits all method of stress relief, but a person- and situation-specific approach to the reduction of anxiety.

One aspect of this multidimensionality has focused on the ideological nature of coping. It has been acknowledged, for instance, that coping strategies can either be religious (Koenig et al. 1998; Krause 1998; Pargament 1997) or secular in orientation (Hampson et al. 1996; Murberg et al. 2004); and, the type of strategy that an individual chooses to rely on will vary depending upon his/her own beliefs and preferences. Despite acknowledgement of this distinction, to our awareness, there has only been one study comparing the use of religious versus secular coping strategies among older adults (Dunn and Horgas 2004). This particular study, although insightful, primarily provided a descriptive account of the frequency of using each strategy (religious and secular). The study did not analyze health outcomes associated with the choice of a particular strategy of coping.

Therefore, the purpose of our study is to examine whether the choice of a religious or a secular coping strategy in older adulthood is associated with a salubrious outcome—specifically, we focus on decreased mortality risk. Furthermore, we explore if any effect(s) that are found differ based on: (1) the social or individual nature of the chosen strategy, as well as (2) the religious ideology of the individual. A better understanding of how to properly regulate stress (particularly in later life) will be beneficial in informing stress response interventions.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows: We first review the literature on coping strategies among older adults, organizing this literature into categories of religious and secular. Within both categories we identify various social and individual approaches that can be used in the coping process. Next, we present a conceptual framework to formalize our research. Our methods are then outlined before turning to a presentation of our findings. In the findings, we begin by replicating prior research and examining the benefits associated with both religious and secular coping strategies. We then add to the literature by first testing the differential effects of individual and social approaches to the use of secular and religious coping strategies, and then testing whether matching coping strategies to personal religious ideologies matters in terms of reducing the risk of mortality. We conclude the article with a discussion of our findings, and also present a number of areas that are likely to be fruitful for future research.

2 Literature Review

Researchers have identified a number of coping strategies that are often utilized in older adulthood. To organize this body of literature, in this review we categorize these strategies into two main types: religious and secular. We examine both types of coping strategies and then identify various individual and social coping approaches that are available within each type.

2.1 Religious Coping Strategies

Koenig et al. (1998) offer a definition of religious coping as “the use of religious beliefs or behaviors to facilitate problem-solving to prevent or alleviate the negative emotional consequences of stressful life circumstances” (p. 513). The use of religion as a coping strategy is separate and distinct from the general concept of religiosity (which is often operationalized in many studies using the frequency of prayer or church attendance). Indeed, religious coping is considered to be a coping method that is consciously chosen by individuals in their efforts to deal with stressful situations.

Among older adults, religious coping (e.g., seeking a connection with God, seeking support from congregation members, giving religious help to others) has been shown to improve self-perceived mental and physical health (Koenig et al. 1998) and, in some instances, has even been shown to result in better objectively measured health (Krause 1998; Wachholtz and Pargament 2005). It should be noted, though, that this type of coping has not always been shown to result in positive outcomes. In fact, there is some evidence to indicate that spiritual discontent and the fear of reappraisal from God’s powers might actually be associated with worse, instead of better, mental and physical health—particularly in older adult populations (Koenig et al. 1998; Parenteau et al. 2011; Pargament et al. 1998).

2.1.1 Individual and Social Approaches to Religious Coping

Two approaches to religious coping have been identified in the literature. These approaches include the use of both individual and socially focused coping activities (Stark and Glock 1968). Individual approaches to religious coping include activities like engaging in private prayer or reading religious texts in order to alleviate stress and anxiety. These approaches to coping are specific ways of expressing one’s personal faith that do not necessitate social engagement with a religious community (Wuthnow 1991). Individually focused approaches to religious coping have been shown to influence health outcomes in many instances. For example, the individual religious coping practice of prayer was positively associated with optimism among a sample of middle-aged adults scheduled for cardiac surgery (Ai et al. 1998). Moreover, research has shown that Americans who rely on prayer as a coping strategy are more likely to engage in health protective behaviors (Wachholtz and Sambamoorthi 2011).

Social approaches to religious coping deal with the integration of individuals into a broader community of support. These approaches include activities such as attending religious services or joining Bible study (or, other religiously-oriented) groups in order to alleviate stress and anxiety (Stark and Glock 1968). Although frequency of church attendance is often included as a general measure of religiosity in studies of coping behaviors, church attendance is rarely included as a distinct approach to coping. Yet, church attendance has consistently been shown to be associated with better health outcomes (e.g. fewer medical diagnoses, less perceived severity of illness, lower rates of depression, and greater quality of life) (Koenig et al. 1998). Frequent church attenders have also been shown to have a lower mortality risk than those who attend religious services less frequently (Strawbridge et al. 1997).

Despite clear distinctions between individual and social approaches to religious coping, many researchers have often combined these two coping approaches into a single measure (Bjorck and Thurman 2007; Krause 1998)—examining the overall effect of religious coping on various health and lifestyle outcomes. For example, Krause (1998) combined both individual and social approaches to religious coping and investigated the joint effect on different life roles, finding a positive effect of religious coping for less educated and older adults. Bjorck and Thurman (2007) also combined individual and social coping approaches to examine the effect of religious coping on psychological functioning. They found that religious coping buffered against the effects of negative psychological events. Additionally, in a study of HIV-positive African-American women, a combined measure of religious coping was shown to negatively correlate with levels of anxiety (Woods et al. 1999).

2.2 Secular Coping Strategies

In addition to religious coping strategies, there are also a number of non-religious, or secular, coping strategies that exist. Within this type of coping, the scholarly literature also focuses on distinct approaches: first, active versus passive coping—both of which are generally considered to be more individually oriented. Second, as a social approach to secular coping, a recent trend has been to examine various forms of collective engagement, such as volunteering.

2.2.1 Individual Approaches to Secular Coping: Active Versus Passive

Two of the most commonly studied individual approaches to secular coping include active and passive coping, which are distinct independent constructs (Snow-Turek et al. 1996). Active coping involves behaviors that result in an awareness of the stressor, followed by attempts to reduce the negative outcome(s). Passive (or, avoidant) coping behaviors refer to activities that lead one to withdraw and/or surrender control over pain.Footnote 1 Active coping can include things such as distraction or activity management, while passive coping can include things such as rest or avoidance (Brown and Nicassio 1987).

Engaging in active coping behaviors may be more beneficial to older adults’ health than engaging in passive coping behaviors. Indeed, in a qualitative study of coping among older adults aged 65 and above, those who utilized more active coping behaviors were characterized as “striving to maintain independence and control [through] maneuvering between available resources” (Dunér and Nordström 2005, p. 444), whereas those who utilized more passive coping behaviors were believed to have “given up control over their lives” (p. 446). Moreover, among older adults suffering from acute and chronic physical health problems, active coping was shown to be positively associated with better mental health (Koenig et al. 1998); and, in a study of older adults coping with osteoarthritis, engaging in active coping behaviors was shown to be related to less depressive affect at follow up (Hampson et al. 1996).

Passive coping behaviors, on the other hand, have been shown to increase individuals’ negative affect (Hampson et al. 1996). Researchers, for instance, have found that those who perceive themselves to be in poor health are more prone to engage in passive coping behaviors and are more likely to have greater depressive symptoms (Hampson et al. 1996). There is also evidence to indicate that engaging in passive coping behaviors can actually lead to an increase in mortality risk. Indeed, in a longitudinal study among veterans with end-stage renal disease, avoidant (i.e., passive) coping was associated with increased mortality risk, whereas active coping was not (Wolf and Mori 2009).

2.2.2 Social Approaches to Secular Coping

In recent years, scholars have begun to explore the extent to which social approaches to coping that are non-religiously oriented can affect one’s health. Many of these studies have examined the relationship between volunteering, as a general activity, and various health outcomes (see Okun et al. 2013 for a meta-analysis). Volunteering among older adults, for example, has been shown to be associated with a significant reduction in depressive symptoms (Banerjee et al. 2010). Moreover, longitudinal findings indicate that well-being and volunteering can mutually influence one another. Thoits and Hewitt (2001), for instance, found that individuals who had better physical and mental health were not only more likely to engage in volunteer work, but were also more likely to have the necessary “internal coping resources that expedite[d] seeking out volunteer opportunities, becoming involved, [and] staying involved” (p. 118).

Although researchers have long explored the nature of religious volunteering (see for instance, Campbell and Yonish 2003; Jackson et al. 1995; Wymer 1997), several studies have found that volunteering is positively associated with increased health and well-being independent of religious participation. A recent meta-analysis, for instance, found that even when controlling for various social and demographic covariates, including participation in religious activities, volunteers experienced a 25 % reduction in mortality risk on average compared to non-volunteers (Okun et al. 2013).

Despite this salubrious effect of volunteering on health and well-being, there is little research examining whether older adults (in particular) consciously select volunteer work as a means to cope with negative stressors. One recent exception, however, is a study that examined the relationship between coping strategies and health outcomes among a sample of retirees in the UK (Lowis et al. 2011). The findings from this study revealed that some retirees do, in fact, engage in helping behaviors as a way to cope (e.g., “helping others, which also helps me”). The findings also indicated that “giving to others” was also highly ranked among the retirees as a secular approach to coping. Thus, it is possible that volunteering may offer compensatory and beneficial effects that positively impact how individuals view life’s stressors and may ultimately facilitate relaxation and recovery—thereby enabling them to better cope in other life domains (Jiranek et al. 2014).

3 Conceptual Framework

Given the evidence that both religious and secular coping strategies can be useful for dealing with stress in later life, in the current study we investigate whether, and to what extent, these two types of coping strategies are beneficial for older adults of differing religious ideologies—that is, for both religious and non-religious individuals. One specific component of being able to manage stress in later life relates to the ability to manage oneself and one’s environment, across physical, social, and psychological perspectives. The match, or balance, between an individual’s functional competence (or, ability) and his/her surrounding environment is known as person–environment (P–E) fit (Lawton and Nahemow 1973). P–E fit is an important component of aging, as accommodating environments that support declines in functional capacity help maintain overall health, independence, and well-being in later life (Iwarsson et al. 2007; Oswald et al. 2007; Wahl et al. 2012). Thus, according to P–F fit, the relationship between an individual’s characteristics and beliefs, and elements of his/her environment should be important (Kristof-Brown and Guay 2010).

Although P–E fit theory is generally applied to organizational settings, we conceptually extend the theory to individuals’ ideological environment. We posit, for example, that a religious individual may be more likely to benefit from the use of a religious coping strategy than a non-religious individual. Religious individuals may also differ in the approach to coping that they choose to utilize. Some may draw on more internal psychological resources (such as independently praying or reading religious literature). Others, however, may desire to develop social connections; and may, therefore, physically place themselves within religious environments (e.g., attending religious services, Bible studies, or other religious events) in order to cope with stressful situations.

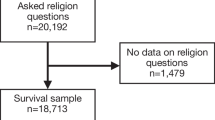

With this conceptual framework in mind, in this study we investigate differences in the effect of various coping strategies on mortality risk for older adults who self-classify as either religious or non-religious. As shown in Fig. 1, our conceptual model indicates that older adults will choose a coping strategy (either religious or secular) based on their own personal beliefs and preferences, and within that strategy they will rely on the use of either individual or social coping approaches.

4 Method

4.1 Data

The data for this study was obtained from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS). The WLS follows a randomly selected sample of 10,317 men and women who graduated from Wisconsin high schools in 1957. Although the sample is broadly representative of predominantly Caucasian individuals, the sample has a low representation of ethnic minorities. For the purposes of this study, we focus specifically on respondents who answered questions of interest relating to the use of coping strategies (reported below) in three waves of the data: 1992, 2004, and 2009 (n = 3,146). Respondents in this sub-sample were majority female (approximately 55 %), and had a mean age of 70 in 2009 (the age range was from 69 to 72). Full details about the WLS, including the samples from each year, response rates, weightings, and interview formats can be found on the WLS website: http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/wlsresearch/pilot/.

4.1.1 Dependent Variable

Our dependent variable of interest is mortality status in 2009. The mortality of each respondent was determined using National Death Index records. In the dataset, we coded mortality as a dichotomous indicator of alive (coded as "0") or deceased (coded as "1").

4.1.2 Independent Variables

We examined the effects of various coping strategies (assessed in 2004) on mortality status, controlling for a number of potential confounds. Coping strategies were classified as either religious or secular, and coping approaches were included that represented both individual and social activities and behaviors (see Fig. 1).

In terms of religious coping strategies, the more individual form of religious coping involved the use of prayer to cope. Specifically, in the WLS, respondents were asked: When you have problems or difficulties in your family, work, or personal life, how often do you seek comfort through praying? (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, and 4 = often). Respondents were also asked to report how religious they believed themselves to be (1 = not at all religious; 5 = extremely religious). The more social form of religious coping involved attending religious services. In the survey, respondents were asked: When you have problems or difficulties in your family, work, or personal life, how often do you seek comfort through attending a religious or spiritual service? (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, and 4 = often).

In terms of secular coping strategies, two individual forms of secular coping were included in the WLS: active and passive (Carver 1997). Active coping was assessed using eight items taken from the Brief Coping Inventory (e.g. Generally, when you experience a difficult or stressful event, how often do you take actions to try and make the situation better?; response options included:1 = I usually do not do this at all, 2 = I usually do this a little bit, 3 = I usually do this a medium amount, and 4 = I usually do this a lot; α = .82). Passive coping was assessed using nine items from the same inventory and the same response options (e.g. Generally, when you experience a difficult or stressful event, how often do you give up the attempt to cope? α = .67). See “Appendix” for the full-scale items for both active and passive coping. The more social form of secular coping, volunteering, was measured using two items in the WLS taken from the Volunteer Functions Inventory (Clary et al. 1998). These items assessed the extent to which respondents used volunteering as a way to: (1) help them work through their own personal problems, and (2) help them escape their own troubles (1 = not at all important/accurate to 7 = extremely important/accurate). These two items were combined to create a single measure of social secular coping (α = .79).

4.1.2.1 Control Variables

We included a number of control variables in the analysis to account for the possibility that any effects in the relationship between the choice of coping strategy and mortality risk could result from underlying demographic, social, or health factors. Controlling for these factors is important since meta-analyses have consistently shown that the relationship between religious involvement and mortality risk can be explained, in part, by a number of these factors (McCullough et al. 2000).

4.1.2.2 Demographic Controls

Very little variance exists in the age of the respondents in our sample. Still, we controlled for age, as well as gender (1 = male, 0 = female). Both women and older individuals are likely to be more religious than men and younger population groups, and both of these variables have (in some ways) been shown to be associated with mortality risk (McCullough et al. 2000). Other demographic controls included a continuous measure of the number of years of education respondents had, a continuous measure of respondents’ net worth, and a dichotomous indicator of their employment status in 2004 (1 = working for pay, 0 = not working at all).

4.1.2.3 Social Controls

It is possible that general differences in social connectedness or social tendencies might underlie the predicted differential effects of coping strategy on mortality risk. Therefore, we also controlled for a number of social variables. These included: marital status, level of social integration, and the extent of extraversion-like qualities. Research has shown that individuals who have greater social connections are more likely to be in better mental and physical health than those with fewer social connections (Holt-Lunstad et al. 2010; House et al. 1988). Marital status (1 = married, 0 = not married, i.e. separated, divorced, widowed, or never married) was assessed in 2004. Variables measuring the number of hours respondents volunteered per month in the past year, and the number of times they had gotten together with friends (e.g. going out together, visiting each other’s homes) in the past 4 weeks were included to assess the level of social integration of the respondents. Degree of extraversion was assessed by summing six items from the Big Five Inventory (version 4a and 5a: 1 = agree strongly, 6 = disagree strongly; α = .75; John et al. 1991).

4.1.2.4 Health Controls

We also controlled for a number of physical, psychological, and cognitive health variables (in 1992). Physical health was assessed using three variables. First, respondents reported the total number of physician diagnosed medical illnesses based on a list of seventeen potential illnesses: anemia, asthma, arthritis/rheumatism, bronchitis/emphysema, cancer, chronic liver trouble, diabetes, serious back trouble, heart trouble, high blood pressure, circulation problems, kidney or bladder problems, ulcers, allergies, multiple sclerosis, colitis, or some other illness or condition. We also included self-rated evaluations of respondents’ overall health in 2004 (1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, and 5 = excellent), as well as self-described reports of whether respondents ever had any long-term physical or mental conditions, illnesses or disabilities that limited what they were able to do, either on or off the job? (1 = yes, 0 = no).

Health risk behaviors were assessed using self-reports of respondents’ current smoking behavior (1 = yes, the respondent is a regular smoker; 0 = no), drinking behavior (1 = yes the respondent is a regular drinker; 0 = no), and body mass index (BMI). Mental and cognitive health was assessed using four items. First, depression history was assessed by responses to the following question: Have you ever had a time in life lasting 2 weeks or more when nearly every day you felt sad, blue, depressed, or when you lost interest in most things like work, hobbies, or things you usually liked to do for fun? (1 = yes, 0 = no). Second, respondents were asked to report their lifetime prevalence of major stressful events (e.g. natural disaster, served in combat, witnessed severe injury or death, debt or financial loss, legal difficulties, incarceration, spousal abuse, child seriously ill or injured, etc.). Lastly (representing the third and fourth components of the mental and cognitive health assessment), cognitive health was measured in 2004, and assessed via respondents’ short-term memory scores for a list of random words (0–10 words correct), and also through a cognitive letter fluency test in which they were asked to list as many words as possible that started with a specific letter.

5 Results

5.1 Part 1: Replicating Past Research

We first examined whether an individual’s choice of coping strategy was dependent upon his/her own personal ideological stance with regard to religion. To do so, we ran a series of ANOVAs examining the influence of religiosity (religious versus non-religious) on the different coping strategies in the analysis. Not surprisingly, when compared to non-religious respondents, religious respondents were more likely to rely on religiously oriented coping strategies—both social (i.e., attending religious services) and individual (i.e., prayer) approaches, ps < .001 (see Table 1). However, religious and non-religious respondents, alike, were equally as likely to rely on secular coping strategies that focused on individual behaviors—that is, active coping behaviors, F(1, 6538) = .18, p = .67, and passive coping behaviors, F(1, 6536) = 2.38, p = .12. Finally, the findings from the ANOVA indicated that religious respondents were more likely to report having used volunteering as a means to cope than non-religious respondents, p < .001 (Table 1)—this, despite the fact that opportunities to volunteer may not necessarily be linked to a religious institution.

We next estimated a hierarchical binomial logistic regression model to examine the relationship between different coping strategies in 2004 and mortality risk 5 years later (in 2009), controlling for a number of potential confounds. Step 1 included our demographic control variables, Step 2 included our social control variables, and Step 3 included the different health-related control variables that were previously outlined. In Step 4, we examined the main effects of each of the coping strategies (mean-centered) on later mortality risk (see Table 2 for descriptive statistics and inter-correlations among the various coping strategies).

As shown in Table 3 (Step 4), respondents who reported being more religious in 2004 had a marginally lower risk of mortality 5 years later, β = −0.25, p = .07, Odds ratio = 0.74, 95 % CI [.59, 1.03]. However, individual and social religious coping behaviors predicted mortality risk in different ways. When focusing on the sample as a whole, attending church more frequently to cope was associated with a reduction in mortality risk, β = −0.33, p = .006, Odds ratio = 0.72, 95 % CI [.57, .91], while praying more frequently to cope was associated with an increase in mortality risk, β = 0.51, p < .001, Odds ratio = 1.66, 95 % CI [1.26, 2.20]. Furthermore, active coping strategies were associated with marginally lower mortality risk, β = −0.28, p = .10, Odds ratio = 0.75, 95 % CI [.54, 1.06]. No other main effects were significant.

5.2 Part 2: Matching the Health Benefits of Coping Strategies (Testing P–E Fit)

We next examined the effect of interactions between respondents’ religiosity (or, lack thereof) and the various coping approaches by entering interaction terms into Step 5 of the model. As can be seen from Table 4, the interactions between religiosity and church attendance, β = −0.59, p = .05, Odds ratio = 0.56, 95 % CI [.31, 1.00], religiosity and passive coping, β = 1.62, p = .005, Odds ratio = 0.20, 95 % CI [.06, .62], and religiosity and volunteering, β = 0.40, p = .03, Odds ratio = 1.50, 95 % CI [1.04, 2.15] were all significant, while the interactions between religiosity and the other variables did not approach significance. In order to examine these interactions in more depth we split the data file by those who self-classified as religious (n = 2,619) and those who did not (n = 527), and examined the effects of the various coping strategies within each group (Step 4), controlling for all previously mentioned covariates (Steps 1–3).

5.2.1 Non-religious Respondents

As can be seen from Table 4, for non-religious individuals there was no effect of religious coping strategies on later mortality risk. Moreover, there was no effect of active coping approaches for non-religious individuals. What really seemed to predict later mortality risk for non-religious respondents was their use of passive coping styles, which predicted higher mortality risk 5 years later, β = 1.43, p = .02, Odds ratio = 4.17, 95 % CI [1.23, 14.07], and their use of volunteering to cope, which predicted a lower mortality risk, β = −0.47, p = .03, Odds ratio = 0.63, 95 % CI [.41, .95].

5.2.2 Religious Respondents

For religious individuals there was no effect of passive coping strategies on later mortality risk. Instead, the strongest effects were seen for religious behaviors. Interestingly, using prayer to cope predicted a higher mortality risk 5 years later, β = 0.45, p = .01, Odds ratio = 1.57, 95 % CI [1.11, 2.22], and using church attendance to cope was associated with a lower later mortality risk, β = −0.46, p < .001, Odds ratio = 0.63, 95 % CI [.50, .80]. In addition, religious individuals benefitted from more active coping strategies, β = −0.39, p = .04, Odds ratio = 0.67, 95 % CI [.47, .97]. Surprisingly, for those who were religious, volunteering actually had a marginally significant effect of increasing their mortality risk, β = 0.12, p = .08, Odds ratio = 1.13, 95 % CI [.99, 1.29].

6 Discussion

In our overall sample of respondents, we replicated prior research on the benefits of religious coping strategies (Krause 1998; Strawbridge et al. 1997). However, we also distinguished between individual and social approaches to coping. Our findings indicated that the use of religious coping strategies that were more individual in nature (such as prayer) actually increased mortality risk in older adults. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of such a finding. Although there has certainly been prior research exploring the relationship between coping and well-being, this research has focused mainly on health-related outcomes other than mortality risk. Moreover, this research has not examined distinctions between social and individual coping approaches within a single predictive model.

Our results also suggest that attending church to cope with stress, controlling for the effect of the use of prayer as a coping strategy, may be beneficial for one’s health. However, praying to cope, controlling for the effect of attending church as a coping strategy, may be detrimental for one’s health. Although the two approaches seem to co-occur (see Table 1), when their independent effects are teased apart, social approaches to religious coping seem to be more protective than individual approaches. This finding may be a result of the social nature of attending religious services in general. Indeed, qualitative studies have provided possible explanations as to why church attendance might serve as an effective coping strategy. One study, in particular, found that participating in religious services ignites a sense of belonging among older adults living with HIV/AIDS, and buffers against feelings of isolation (Siegel and Schrimshaw 2002). Ultimately, church attendance was shown to affirm the self-worth of these individuals despite their illness.

Social approaches to religious coping, therefore, may be a way for individuals to not only relieve their anxiety, but may also allow them an opportunity to obtain the relevant affirmation(s) needed that will enable them to build their own coping abilities. In general, research has consistently shown that social integration and support can buffer against many negative health outcomes (Thoits 2011)—which would be supportive of this notion. We cannot, however, be certain that social coping approaches act in this way without further evidence. Therefore, we recommend that scholars further investigate why exactly more social approaches to religious coping may be associated with lower mortality risk as opposed to more individual approaches.

In terms of secular coping strategies, in the overall sample we found that the only secular strategy that was associated with lower mortality risk was the extent to which individuals used active coping approaches to deal with their problems and difficulties. This finding is in contrast to prior research (e.g., Wolf and Mori 2009) that has found no effect of active coping on how individuals deal with stress. It is not entirely clear as to why the other two secular strategies were not significant in the model (either passive coping—being the other individual secular approach to coping—or volunteering as a social secular approach to coping). Future research might consider replicating these relationships with the use of other data, since this finding might be a particularity of our sample.

Next, we focused on the relationships laid out in our conceptual model relating to person–environment (P–E) fit and examined the extent to which the match between an individual’s personal and ideological characteristics and their choice of coping strategy mattered in terms of reducing their mortality risk. In examining this relationship, we found that the use of religious coping strategies by non-religious adults had no effect on mortality risk. That is, respondents who self-classified as more secular (than religious) could rely on a religious coping strategy, and this would have no increase or decrease on their risk of mortality. However, the use of certain secular coping strategies did affect their mortality risk. In particular, passive coping (an individual secular approach to coping) was associated with a higher mortality risk while volunteering (a social secular coping approach) was associated with a lower mortality risk.

Among religious respondents, religious coping strategies had the most powerful effects on their risk of mortality. Specifically, church attendance (a social religious coping approach) was associated with a lower mortality risk, while prayer (a more individual religious coping approach) was associated with a higher mortality risk. Taken together, these results support P–E fit theories, which suggest that it is important for individuals to match their own personal ideologies and characteristics with that of their environment, or in this case, their choice of coping strategy (Kristof-Brown and Guay 2010). Without further research it is unclear as to why such a fit should matter, but we speculate that matching one’s coping strategy to his/her level of religiosity can help to affirm one’s own sense of value, which in turn may increase their level of eduaimonic well-being (e.g., happiness and contentment) (Novin et al. 2013). In other words, religious individuals may be more likely to find purpose and meaning when coping in a church setting, which is a social context that matches their own values, whereas non-religious individuals may find their purpose and meaning when coping through volunteering, which is a socially engaging and (in many instances) meaningful activity.

Finally, for religious respondents, we found that there was an additional mortality risk reduction associated with active coping strategies. We speculate that this may result from their use other socially-focused religious coping approaches as part of their repertoire of active coping behaviors (e.g., attending Bible study groups, seeking prayer support from others). Future research should consider more detailed questions regarding the exact behaviors that are associated with active approaches to coping—since these coping approaches may differ for religious and non-religious individuals.

Interestingly, although volunteering was associated with a lower mortality risk among non-religious respondents, it was associated with a higher risk of mortality among religious respondents. This is a striking and surprising finding given prior research suggesting that the benefits of volunteering may be strongest for religious individuals (McDougle et al. 2014; Okun et al. 2013). However, without further replication we cannot make conclusive claims regarding this result.

6.1 Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

Our study has a number of strengths. First, we match individual ideologies to health outcomes associated with the use of various coping strategies. This is something that previous studies have not done. We believe that this is a model that can be applied to the assessment of other types of individual differences (e.g. education, ethnicity), coping strategies, and health outcomes. Moreover, this study highlights the importance of designing interventions to help older adults cope with life stressors that take into account the unique characteristics of the individual. Indeed, health communication studies have long suggested that individuals are more likely to respond to interventions, and to be positively influenced by them, if the interventions match important demographic characteristics of the recipients (Kreuter et al. 1999).

Despite these strengths, there are some limitations associated with this research. First, although the WLS asks respondents about their voluntary involvement (as a social secular approach to coping), the survey does not ask respondents about their specific volunteering activities—thus, it is unclear where respondents volunteered their time. Future research might investigate different types of volunteering (religious versus non-religious) to get a better sense of whether P–E fit is important at this level. It is also unclear which tasks respondents performed while volunteering. Some volunteering tasks are done independently, while other tasks are more social or group-based. Research has shown that when direct social interaction is part of the volunteer experience, well-being can be enhanced compared to when the volunteer experience does not involve direct social interaction (Wheeler et al. 1998). Finally, respondents in the WLS were predominantly Caucasian with a low representation of ethnic minorities. Thus, generalizations of these findings to diverse racial/ethnic groups are cautioned.

7 Conclusion

In this study, we find that it is important for older adults to select coping strategies that match their level of religiosity. We also find that social approaches to coping seem to be more beneficial to the health of older adults than more individual approaches. This is a particularly important finding since older adults often face a number of challenges related to role identity and relationship loss as they progress through the aging cycle. These challenges can ignite a number of stress-inducing experiences that can be detrimental to their health. As a result, it is important to be able to identify and recommend effective coping strategies that will assist older adults in managing their stress and anxiety.

Ultimately, our findings highlight the importance of recommending coping strategies in later life that match individual characteristics and ideologies. This will likely help family members, support groups, loved ones, and/or medical practitioners recommend the most salubrious coping strategy in later life.

Notes

It should be noted that the use of active and passive approaches to secular coping are not mutually exclusive to the use of religious coping strategies. In fact, many religious coping strategies can be either active or passive in nature (e.g., using prayer as an avoidant way of directly dealing with a particular situation). However, for the purposes of this research, we focus on active and passive approaches to coping that are more secular in nature.

References

Ai, A. L., Dunkle, R. E., Peterson, C., & Boiling, S. F. (1998). The role of private prayer in psychological recovery among midlife and aged patients following cardiac surgery. The Gerontologist, 38(5), 591–601.

Aldwin, C. M., Molitor, N.-T., Spiro, A., Levenson, M. R., Molitor, J., & Igarashi, H. (2011). Do stress trajectories predict mortality in older men? Longitudinal findings from the VA normative aging study. Journal of Aging Research,. doi:10.4061/2011/896109.

Banerjee, D., Perry, M., Tran, D., & Arafat, R. (2010). Self-reported health, functional status and chronic disease in community dwelling older adults: Untangling the role of demographics. Journal of Community Health, 35(2), 135–141.

Baumgartner, R. N., Waters, D. L., Gallagher, D., Morley, J. E., & Garry, P. J. (1999). Predictors of skeletal muscle mass in elderly men and women. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 107(2), 123–136.

Bjorck, J. P., & Thurman, J. W. (2007). Negative life events, patterns of positive and negative religious coping, and psychological functioning. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 46(2), 159–167.

Bossé, R., Aldwin, C. M., Levenson, M. R., & Workman-Daniels, K. (1991). How stressful is retirement? Findings from the normative aging study. Journal of Gerontology, 46(1), P9–P14.

Brown, G. K., & Nicassio, P. M. (1987). Development of a questionnaire for the assessment of active and passive coping strategies in chronic pain patients. Pain, 31(1), 53–64.

Campbell, D. E., & Yonish, S. J. (2003). Religion and volunteering in America. In Corwin Smidt (Ed.), Religion as social capital: Producing the common good. Religion as social capital (pp. 87–106). Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press.

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4, 92–100.

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R. D., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen, J., & Meine, P. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: a functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1516–1530.

Dunér, A., & Nordström, M. (2005). Intentions and strategies among elderly people: Coping in everyday life. Journal of Aging Studies, 19(4), 437–451.

Dunn, K. S., & Horgas, A. L. (2004). Religious and nonreligious coping in older adults experiencing chronic pain. Pain Management Nursing, 5(1), 19–28.

Elwell, F., & Maltbie-Crannell, A. D. (1981). The impact of role loss upon coping resources and life satisfaction of the elderly. Journal of Gerontology, 36(2), 223–232.

Hampson, S. E., Glasgow, R. E., & Zeiss, A. M. (1996). Coping with osteoarthritis by older adults. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 9(2), 133–141.

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2007). Aging and loneliness downhill quickly? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(4), 187–191.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316.

House, J. S., Landis, K. R., & Umberson, D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241(4865), 540–545.

Iwarsson, S., Horstmann, V., & Slaug, B. (2007). Housing matters in very old age-yet differently due to ADL dependence level differences. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 14(1), 3–15.

Jackson, E. F., Bachmeier, M. D., Wood, J. R., & Craft, E. A. (1995). Volunteering and charitable giving: do religious and associational ties promote helping behavior? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 24(1), 59–78.

Jiranek, P., Brauchli, R., & Wehner, T. (2014). Beyond paid work: Voluntary work and its salutogenic implications for society. In G. F. Bauer & O. Hämmig (Eds.), Bridging occupational, organizational and public health (pp. 209–229). Netherlands: Springer.

John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). The big five inventory—versions 4a and 54. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research.

Koenig, H. G., Pargament, K. I., & Nielsen, J. (1998). Religious coping and health status in medically ill hospitalized older adults. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 186(9), 513–521.

Kraaij, V., Garnefski, N., & Maes, S. (2002). The joint effects of stress, coping, and coping resources on depressive symptoms in the elderly. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 15(2), 163–177.

Krause, N. (1998). Stressors in highly valued roles, religious coping, and mortality. Psychology and Aging, 13(2), 242.

Kreuter, M. W., Strecher, V. J., & Glassman, B. (1999). One size does not fit all: the case for tailoring print materials. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 21(4), 276–283.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., & Guay, R. P. (2010). Person–environment fit. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 3–50). Washington, DC: APA.

Lawton, M. P.; Nahemow, L. Eisdorfer, C. (Ed); Lawton, M. P. (Ed), (1973). The psychology of development and aging (pp. 619–674). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Lowis, M. J., Jewell, A. J., Jackson, M. I., & Merchang, R. (2011). Religious and secular coping methods used by older adults: An empirical investigation. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, 23, 279–303.

McCullough, M. E., Hoyt, W. T., Larson, D. B., Koenig, H. G., & Thoresen, C. (2000). Religious involvement and mortality: A meta-analytic review. Health Psychology, 19(3), 211.

McDougle, L., Handy, F., Konrath, S., & *Walk, M. (2014). Health outcomes and volunteering: The moderating role of religiosity. Social Indicators Research, 117(2), 337–351.

Moos, R. H., Brennan, P. L., Schutte, K. K., & Moos, B. S. (2006). Older adults’ coping with negative life events: common processes of managing health, interpersonal, and financial/work stressors. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 62(1), 39–59.

Murberg, T. A., Furze, G., & Bru, E. (2004). Avoidance coping styles predict mortality among patients with congestive heart failure: a 6-year follow-up study. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(4), 757–766.

Novin, S., Tso, I., & Konrath, S. (2013). Self-related and other-related pathways to subjective well-being in Japan and the United States. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 995–1014.

Okun, M. A., Yeung, E. W. H., & Brown, S. (2013). Volunteering by older adults and risk of mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 28(2), 564–577.

Oswald, F., Wahl, H.-W., Schilling, O., Nygren, C., Fange, A., Sixsmith, A., et al. (2007). Relationships between housing and healthy aging in very old age. The Gerontologist, 47(1), 96–107.

Parenteau, S. C., Hamilton, N. A., Wu, W., Latinis, K., Waxenberg, L. B., & Brinkmeyer, M. Y. (2011). The mediating role of secular coping strategies in the relationship between religious appraisals and adjustment to chronic pain: the middle road to Damascus. Social Indicators Research, 104(3), 407–425.

Pargament, K. I. (1997). The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, practice, research. New York: Guilford.

Pargament, K. I., Smith, B. W., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. (1998). Patterns of positive and negative coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study or Religion, 37(4), 710–724.

Pearlin, L. I., & Schooler, C. (1978). The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19(March), 2–21.

Siegel, K., & Schrimshaw, E. W. (2002). The perceived benefits of religious and spiritual coping among older adults living with HIV/AIDS. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41(1), 91–102.

Skinner, E. A., Edge, K., Altman, J., & Sherwood, H. (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: a review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 216.

Snow-Turek, A. L., Norris, M. P., & Tan, G. (1996). Active and passive coping strategies in chronic pain patients. Pain, 64(3), 455–462.

Stark, R., & Glock, C. Y. (1968). Patterns of Religious Commitment; I American Piety: The nature of religious commitment. Los Angeles, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Strawbridge, W. J., Cohen, R. D., Shema, S. J., & Kaplan, G. A. (1997). Frequent attendance at religious service and mortality over 28 years. American Journal of Public Health, 87(6), 957–961.

Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(2), 145–161.

Thoits, P. A., & Hewitt, L. N. (2001). Volunteer work and well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(June), 115–131.

Wachholtz, A., & Pargament, K. I. (2005). A comparison of relaxation, spiritual meditation, and secular meditation and cardiac reactivity to a cold pressor task. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 28, 369–384.

Wachholtz, A., & Sambamoorthi, U. (2011). National trends in prayer use as a coping mechanism for health concerns: changes from 2002 to 2007. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 3(2), 67.

Wahl, H. W., Iwarsson, S., & Oswald, F. (2012). Aging well and the environment: Toward an integrative model and research agenda for the future. The Gerontologist, 52(3), 306–316.

Wheeler, J. A., Gorey, K. M., & Greenblatt, B. (1998). The beneficial effects of volunteering for older volunteers and the people they serve: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 47(1), 69–79.

Wolf, E. J., & Mori, D. L. (2009). Avoidant coping as a predictor of mortality in veterans with end-stage renal disease. Health Psychology, 28(3), 330–337.

Woods, T. E., Antoni, M. H., Ironson, G. H., & Kling, D. W. (1999). Religiosity is associated with affective status in symptomatic HIV-infected African-American women. Journal of Health Psychology, 4(3), 317–326.

Wuthnow, R. (1991). Acts of compassion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Wymer, W. W, Jr. (1997). A religious motivation to volunteer? Exploring the linkage between volunteering and religious values. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 5(3), 3–17.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Full Text of Coping Strategy Items

Appendix: Full Text of Coping Strategy Items

Coping strategy | Item(s) |

|---|---|

Religious | |

Attending religious services | When you have problems or difficulties in your family, work, or personal life, how often do you seek comfort through attending a religious or spiritual service? |

Prayer | When you have problems or difficulties in your family, work, or personal life, how often do you seek comfort through praying? |

Secular | |

Active coping | Generally, when you experience a difficult or stressful event… …how often do you concentrate your efforts on doing something about the situation you’re in? …how often do you take actions to try and make the situation better? …how often do you try to see it in a different light or to make it seem more positive? …how often do you try to come up with a strategy about what to do? …how often do you look for something good in what is happening? …how often do you accept the reality of the fact that it has happened? …how often do you learn to live with it? …how often do you think hard about what steps to take? |

Passive coping | Generally, when you experience a difficult or stressful event… …how often do you say to yourself ‘this isn’t real’? …how often do you give up trying to deal with it? …how often do you refuse to believe that it has happened? …how often do you say things to let your unpleasant feelings escape? …how often do you criticize yourself? …how often do you give up the attempt to cope? …how often do you do something to think about it less, such as going to the movies, watching TV, reading, daydreaming, sleeping or shopping? …how often do you express your negative feelings? …how often do you blame yourself for things that happened? |

Volunteering | How important or accurate, for you, is the following reason for why people engage in volunteer activities… …Volunteering helps me work through my own personal problems? …Volunteering is a good escape from my own troubles? |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McDougle, L., Konrath, S., Walk, M. et al. Religious and Secular Coping Strategies and Mortality Risk among Older Adults. Soc Indic Res 125, 677–694 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0852-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0852-y