Abstract

The current understanding of work in I-O psychology is built fundamentally on the concept of paid labor. We believe that this angle is too narrow and discuss current as well as prospective strands of research on paid and unpaid work. In addition, we highlight the potential of volunteering with regard to life domain balance by drawing on different empirical results. First, it could be shown that volunteering can positively influence the appraisals of stressors. Second, due to their volunteer work individuals can build up resources that can be transferred to other life domains. And finally, volunteering facilitates relaxation/recovery, enabling individuals to better adapt to and fulfill tasks and responsibilities in other life domains. Results from our own research indicate the compensatory and beneficial potential of volunteering. However, there seems to be an optimum, suggesting that individuals who volunteer with a medium frequency experience minimal conflict between life domains. We conclude by discussing from a psychology perspective the health-promoting potential of income equality guaranteed by a utopian basic income.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Beyond the Context of Gainful Employment

The roots of North American work psychology are strongly connected with the idea and analysis of industrial labor as reflected in the I-O psychology domain, where the “I” stands for industrial. In one of the seminal definitions of this scientific branch, the main concept is “the relationship between man and the world of work … in the process of making a living” (Guion, 1965, p. 817). The last part of the definition hints at the extrinsic properties contained in this understanding of work, which is fundamentally concerned with the process of gaining material resources. That is, making a living refers to the existential issue of managing to pay the monthly bills. Hence, the current understanding of and research on work is built extensively and almost exclusively on the foundation of paid labor or gainful employment. According to Taylor (2004), in the twentieth century this reductionism was driven by transitions during industrialization that left a public, primarily male-dominated domain separated from a private, non-economic domain organized exclusively by females. Today, the question arises as to how such a delimited industrial understanding of work in the sense of traditional employment relations can account for current and prospective concepts of work, when considering phenomena such as part-time work, unemployment, multiple jobs, precarious working conditions, and the like.

With the rise of positive psychology in the late 1990s, novel concepts dealing with resource-oriented paradigms emanated. This presented new opportunities to understand traditional constructs, which were formerly based mainly on a pathology and strain perspective (see Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). In occupational health psychology, the salutogenic approach has been applied increasingly to the context of paid work in recent years (e.g., Busch, Roscher, Kalytta, & Ducki, 2009; Cox, Taris, & Nielsen, 2010). We argue that if salutogenic approaches are relevant in the profit sector, they should be considered essential in the non-profit sector, where meaning plays an even more important role (Wehner, Mieg, & Güntert, 2006) and where greater perceived autonomy should serve as a breeding ground for sense of coherence (Udris, 2006). In our view, volunteers in non-profit organizations are not just engaged for moral or altruistic reasons but also because the activity itself is rewarding (Deci & Ryan, 2000) and bears personality development potential (Morf & Weber, 2000).

In this contribution we will critically examine the tacit consent concerning work activity as paid labor. That is, in the realm of I-O psychology, an implicitly accepted concept of work is applied that builds on the premise of an employment relationship inherent to a traditionalist understanding of work and society. From our perspective, this conception ignores certain forms of autonomy that go beyond a paid employment relationship. Understanding and investigating volunteering as an emancipated, salutogenic form of work has appears promising to us. In the following, we discuss unaddressed issues around health with regard to volunteering from what we perceive as a holistic I-O psychology perspective. Although empirical evidence substantiates the belief that volunteering per se has a strong meaning-making potential, a topic that has not yet been addressed is how volunteer work as an activity positions itself with regard to an imagined ideal concept of work and to the construct of gainful employment. Furthermore, the question remains whether and how volunteering can be conceived as a resource. Taking a life domain balance perspective, we try to answer this question and break new scientific ground by presenting initial research findings that substantiate our line of thought. We conclude by linking the resource approach of volunteering with the utopian idea of a basic income, which builds on a humanistic conception of work and society.

2 From a Pathogenic Towards an Integrated Understanding of Work

During the 1950s and 1960s one central assumption of industrial psychology regarding the quality of work was related to raises in pay and reduction of time on the job. A worker who earned more, and had more time to spend and enjoy his earnings, was considered a happy worker from a labor policy perspective (Sauer, 2011). However, as both rationalization and work intensity increased, so did the workers’ health problems, which could scarcely be compensated by mere raises in pay. The adverse effects of physically demanding to health-threatening forms of labor became gradually more recognized, and the intention to address these issues by work council representatives and policy makers increased. Consequently, work conditions received growing attention in various social movements and discussions on work (Sauer, 2011).

2.1 Work Engagement and Burnout

The impact of different conditions of work on the individual can take many forms, ranging from negative to positive effects. In the research on work and health, a strain approach can be distinguished and delineated from a resource approach. To date, the demands reflected in the pathogenic potential of work are well investigated and documented (see Ganster & Schaubroeck, 1991), and the positive potential of certain work-related attitudes and beliefs is recently being discussed, including for example the relationship between efficacy beliefs and work engagement (Llorens, Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, 2007; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). In general terms, as the research on both ends of the strain-resource-continuum has progressed, the dichotomy has become less strict, as many instruments have been consolidated to measure both stress and resources (e.g., Busch et al., 2009). Nevertheless, the issue of stress as a direct and indirect determinant of cardiovascular disease, which is one of the leading causes of death, is surely essential in terms of prevention, when it comes to strain in the workplace. Accordingly, I-O psychology has been concerned for decades with the negative effects of work (see Spector, Zapf, Chen, & Frese, 2000). In occupational health psychology, which was quicker to consider salutogenic influences, a slow but steady paradigm change from research on stress has been taking place, and it is expected that, besides other resource-related constructs, more and more attention will be devoted to work engagement in the future (Macik-Frey, Quick, & Nelson, 2007). In traditional I-O psychology, generally speaking, a paradigmatic focus on stress, strain, and demands is still present, and it remains to be seen whether positive psychology will impact on this branch as much as it has on occupational health research. Currently, the introduction and application of constructs like work engagement seem to indicate such a trend (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004).

The ideal image of work as a mentally enriching, creativity-laden, and enthusiasm infused activity is somewhat reflected in the current proliferation of the construct of work engagement (Bakker, Schaufeli, Leiter, & Taris, 2008). This perception and understanding of work contrasts with the term burnout, which is conceived as “the erosion of engagement” by Schaufeli, Leiter, and Maslach (2009, p. 215) and appears to be overused in the public sphere due to differing cultural reasons. As Schaufeli et al. (2009) suggest, the use of the term burnout in the United States is less stigmatized, since it is non-medical, whereas in Europe burnout as a medical diagnosis is perceived as a key to recovery. An interpretation derived from these cultural applications and implications of burnout could be that it serves as an exit door from a working life that is more and more characterized by a decline in structure, is low in meaningfulness especially in fragmented work tasks, and is permeated with a rise in inter-organizational and inter-individual competition.

Viktor Frankl’s (1985) well-known book, Man’s Search for Meaning, addresses the existential relevance of meaning for human well-being. According to Frankl, frustrating individuals’ will for meaning creates an existential vacuum that is infused by apathy. With regard to working life, it is obvious that people’s failure to generate meaning can potentially harm their health. In addition, with the erosion of family and community life (Putnam, 2000), individuals might tend to identify more and more with their colleagues and their work, thus attaching outstanding importance to these work-related ties. Hence, any fundamental change at work combined with social recession (Myers, 2000), can harm especially predisposed individuals and might eventually contribute to burnout. According to Schein (1980), who promotes a complex idea of man, the same individuals can have different needs in different parts of the same formal organization and might prevent alienation in this formal context by satisfying their social and self-actualizing needs in unions or informal working groups. Turning to volunteering may help people to impede social recession and satisfy rather intrinsic needs such as meaningfulness.

2.2 Meaningfulness and Its Emotional Content

If it is assumed that “the desire for meaning is viewed as a basic motivation” (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2003, p. 95), it should be a core element focus of work psychology. According to Antonovsky and Franke (1997), individuals’ lives are meaningful when they perceive purpose in the activities they perform and when the purpose is sustained over their lifespan. Whether and how meaningfulness can help people to cope with the daily stressors imposed on them by different externalities, ranging from daily hassles to severe life-threatening situations, is at the center of the sense of coherence concept. For Antonovsky and Franke, meaningfulness plays a special role as it bears motivating potential. They suggest that individuals who scored high on this component were predominantly speaking of areas of life that made sense and mattered to them emotionally. Thus, in contrast to the components of comprehensibility and manageability, meaningfulness is characterized not only by cognitive but also by emotional means (Antonovsky & Franke, 1997). This is important to note with regard to volunteering, which has been shown empirically (Wehner et al., 2006) to be based strongly upon meaning and is both cognitive and emotional in nature. Paid work, in contrast, tends to suffer from a kind of déformation professionelle, implying that emotional reactions, such as empathy, are not an expected part of vocational behavior. Accordingly, the objective of many forms of vocational training in social sector occupations and elsewhere is to overrule emotions by cognitions. With regard to the social sector, Ho and Yuen (2010) emphasize the necessity of value involvement and tackle the myth of a positivist conception of social work. According to Ho and Yuen, value-neutrality and “value-detachment in the daily practice of social work” (2010, p. 5) rooted in a strictly positivist conception of social work can produce barriers between social workers and clients and thus lead to a decrease in mutual understanding. That is, common vocabulary and emotional reactions in professionals tend to wither away through the process of becoming professional. When looking at I-O psychology, positive emotions are neglected insofar as mainly constructs, such as negative affectivity, are focused or treated as sources of disturbance, both substantially and statistically (e.g., Schaubroeck, Ganster, & Fox, 1992; Spector et al., 2000). This clearly shows the negative connotations attached to affectivity in the workplace by academia, as well as by industry.

On the whole, it seems obvious that most volunteers in the social sector sustain an unprofessional, layperson view on things containing both cognitive and emotional behavioral and attitudinal components. Conciliating feeling, thought, and action appears to work best in voluntary work objectives where there is enough autonomy to approach a work objective, be it person- or object-related, in a more intuitive fashion as opposed to gainful employment, which is more often attuned to a positivist, professional code of conduct (Ho & Yuen, 2010). There is no question that there are pros and cons in the self-conceptions of both domains – which, however, we will have to leave unaddressed at this point – and that there should be differences in the way people subjectively experience their paid work versus other forms of work.

2.3 Voluntary Work Activity

Concerning paid work, Hackman and Oldham (1975) showed that individual perceptions of work deal with the meaning derived from it or rooted in the activity. Understanding structures inherent to work design that enhance both personality and health in employees, fueled by humane working conditions, was a core research focus in the works of European I-O psychologists in the second half of the previous century, as is reflected in the sociotechnical systems approach (Emery & Thorsrud, 1982; Rice, 1958; Trist & Bamforth, 1951). According to Udris (2006), in future concepts of I-O psychology, the structure- and system-based approach should be complemented by the concept of salutogenesis, which stresses individual aspects. Taking the instrument of subjective work analysis (Udris & Alioth, 1980) as a conceptual starting point, Rimann and Udris (1997) developed a survey incorporating salutogenic resources in addition to job demands. Accordingly, the instrument, called SALSA (Udris & Rimann, 1999), measures personal, organizational, and social resources with regard to occupational health (see Ulich, 2005).

Wehner et al. (2006) define voluntary social work activity as “unpaid, organized social work, which requires an expenditure of time and could also be carried out by a third person and could potentially be remunerated” (p. 20). Wehner et al.’s modus operandi initially took account of previously and universally proven methods of work psychology. Hence, when starting research on volunteering, Wehner et al. adapted a conception of job design characteristics by Ulich (2005), which integrated works from European sociotechnical systems research (Cherns, 1976; Emery & Emery, 1974; Emery & Thorsrud, 1976). Those works show an exceptional “degree of agreement” (Trist, 1981, p. 31) with the North American classic among work design in work psychology – specifically, the Job Diagnostic Survey (JDS) (Hackman & Oldham, 1975). Wehner et al. used JDS-related criteria of humane working conditions in the sense of Ulich (2005), namely, meaningfulness, time flexibility, learning and development opportunities, skill variety, social interaction, autonomy, and task identity in different samples consisting of, among others, (a) volunteers, and (b) employees. The participants were asked to rate seven of the JDS-related criteria, one of which being meaningfulness, on a scale ranging from 1 (very important) to 7 (least important). Whereas volunteers rated meaningfulness on average with 1.3, employees attached less importance to it, reflected in an average rating of 3.7. Additionally, it was found that meaningfulness was delimited from the other aspects such as autonomy or safety. Therefore, Wehner et al. concluded that the meaning-making motive in volunteers should be regarded as essential (Table 13.1).

In a more recent study on hospice volunteers Güntert, Barry, and Wehner (2010) investigated resources and stressors as well as job and organizational characteristics. One major aim of the study was to find out whether the inclusion of work design inventories in addition to an established instrument, namely, the HIV Volunteer Inventory (Guinan & McCallum, 1991), would provide incremental variance in explaining volunteers’ satisfactionFootnote 1 and burnout. With regard to satisfaction and in accordance with the authors’ hypothesis it did so to a considerable extent, as an additional 14 % of variance in satisfaction could be explained (Güntert et al., 2010). More importantly, by using the established HIV Volunteer Inventory, they found that volunteers in hospice care showed lower levels of stress and even felt enriched by their voluntary work (Güntert et al., 2010) as opposed to AIDS volunteers in comparable studies (Claxton, Catalan, & Burgess, 1998; Ross, Greenfield, & Bennett, 1999). Results of further studies on volunteering in palliative care (Claxton-Oldfield & Claxton-Oldfield, 2007; Field & Johnson, 1993) pointed in the same direction. Consequently, these results and this initial finding led us to reflect further on the role of volunteering with regard to different forms of work and concerning health, which will be discussed in the following sections.

3 Subjective Spaces of Meaning

Looking at delimited systems and focusing solely on one form of work – namely, gainful employment – is a paradigm of I-O psychology research. In that paradigm, traditional employment relations are still implicitly assumed, leaving certain transformations unaddressed, such as smaller workplaces admitting more informal interaction, a rise in flexibility and fragmentation, and organizational adaptation to parenting needs of their male and female employees (Guest, 2004). Thus, to account for and learn from currently emerging alternative phenomena, it is necessary to seize the opportunity to analyze and compare the different forms of work that are emerging due to sociotechnical and sociocultural transitions.

When it comes to comparing different forms, apart from measuring meaningfulness and associated emotional responses that individuals attach to gainful employment directly, it is important to first understand subjective-evaluative aspects regarding varieties of work. At the same time, it seems fruitful to compare gainful employment, for instance in relation to volunteering, by positioning both in subjective mental models. In a grid study, Mösken, Dick, and Wehner (2010) adapted qualitative methodology to visualize and analyze mental models and to gain insight into the complexity of individual cases, considered in relation to each other as well as in the aggregate. Unfolding individual perceptions derived from biographies of volunteers helps to model inter-individually varying sculptural sketches of activities that otherwise remain known only to the individual in question. The aggregate of various models helps us to understand which and how many attributes are assigned to different activities by a group of participants.

This methodology is different from regular work analysis, such as survey methodology, which builds on constructs that are introduced by investigators themselves, implying that the investigator knows of the very nature of certain constructs. In the grid technique, this assumption does not guide the researcher’s line of action. Here, constructs are developed cooperatively. The only specification in this research design appears in presenting the activities, which participants are asked to make statements on (Mösken et al., 2010). Hence, by building on Kelly (1986) and Kelly’s construct theory, Mösken et al. (2010) aimed to evoke a subjective account and to test it via factor analysis.Footnote 2 The resulting subjective space of meaning (SSM) was obtained by applying a semi-structured, narrative grid interview (Fromm, 1995). The grid technique is based on the idea of explicating individual perceptions that build on specific individual constructs (Mösken et al., 2010) after presenting certain elements. The major goal is to detect attributes and motives regarding different types of activity by participants who have experience in both gainful employment and volunteering. To do so, Mösken et al. presented three elements at a timeFootnote 3, each comprising different types of activity, to the participants, who were asked to pair two elements due to perceptual similarity and to separate the third element perceived to differ from the other two. This resulted in triads, with two elements being paired on the basis of the constructs applied to differentiate activities or elements, respectively. These constructs can be conceived as the participants’ reasons to distinguish the elements and referred to such notions as spontaneous or planned (see Fig. 13.1).

As the two subjective models make evident, there are inter-individually differing spaces of meaning, and different individual motives emerge as relevant with regard to the different activities.

Three central results of the study by Mösken et al. (2010) are:

-

Overall, the SSM showed that on a subjectively perceived continuum, volunteering is closer to an ideal conception of activity.

-

There is a shared spectrum of meaning attached to both volunteering and gainful employment comprising aspects such as duty, public, well-being, effort, pretense, development, recognition, and activity.

-

Volunteering receives more attributes or, in terms of the repertory grid technique, more constructs than gainful employment, which shows the great diversity inherent to volunteering.

Looking at the grids in the aggregate, consisting of 20 cases, it becomes clear that there are major differences when it comes to placing volunteering and work activity in relation to each other and based on a subjectively conceived ideal of activity. The individual SSM show that volunteering is perceived as being closer to an ideal activity. Consequently, this supports evidence of the special role that volunteering as an activity plays in the lives of volunteers.

Although there is common ground concerning volunteering and work insofar as participants perceive volunteering as one form of work, the results also indicate that volunteering has certain characteristics that differentiate it clearly from gainful employment. These delineating characteristics include admitting emotions, experiencing community, and self-determination during the activity (Mösken et al., 2010).

Concerning work-life balance or life domain balance, the SSM seems relevant when taking into account that there is still no consensus on the balance and conflict of different domains. Based on the results, no generalization can be made concerning which activities are assigned to which domains, and thus speaking of a dichotomy of paid work and family life is not conducive. In other words, these results show that different people assign the same activities to different domains, which they deem important with regard to different constructs. The results are in line with the functional approach applied to volunteering, comprising the notion that a great deal of human behavior is motivated by different goals and needs and thus varies from individual to individual (Clary et al., 1998). According to the functional approach, the very same attitudes and behavioral outcomes of individuals can be accountable for differing psychological functions. Going beyond the paradigm of social psychology, which for decades has been concerned with analyzing the dichotomy of prosocial behavior by interpreting it as either egoist or altruist, these results point up the necessity to perceive the motives of volunteering as multi-functional. To sum up, narrowing volunteering down to an either altruist or egoist motive is just as shortsighted as establishing a dichotomy regarding work and family and then looking for conflict between the two.

4 The Potential of Volunteering Concerning Life Domain Balance

With the sweeping change of social, economic, and technological structures over the last decades, both women and men have expressed interest in a balanced life, mainly referred to as work-life balance. However, due to increased responsibilities within various life domains (such as work, family, friends, sports, volunteering), greater performance pressures, increased hours spent at the workplace, and technical advancements (such as smartphones) that blur boundaries between work and personal life (Burke, 2000; Jones, Burke, & Westman, 2006: Greenhaus & Allen, 2010), employees today are especially challenged to balance their work and other life domains in order to meet the various needs and demands (Allen, Herst, Bruck, & Sutton, 2000). This challenge may become a stressor, and conflicts between different life domains may occur. This is called work-family conflict or work-life conflict (Allen et al., 2000). However, researchers have argued that workers may also benefit from combining work and personal life; this is called work-family enrichment or work-life enrichment (Greenhaus & Allen, 2010; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006).

4.1 From Work-Life Balance to Life Domain Balance

As the research on work-life balance is concerned with questions about the relation between paid work and personal life (Wiese, 2007), the term work-life balance is an unfortunate choice (Resch & Bamberg, 2005). It may lead to the conclusion that it refers to a balance or a balancing between work and life. However, since work is a central part of life and there are various forms (e.g., voluntary work, housework, education work) outside paid work, the term life domain balance seems more appropriate (Ulich & Wiese, 2011). A comprehensive understanding of balancing, combining, or integrating different life domains will allow us to refer to these different life domains, which are individually relevant for each person (Brauchli, Hämmig, Güntert, Bauer, & Wehner, 2012) and can potentially come into conflict with or enrich one another (Ulich & Wiese, 2011). Keeping this broad view on the interaction of diverse life domains in mind, voluntary work activity or volunteering gains relevance, considering its effects on the individual. Volunteering is a specific field of activity beyond paid work, and it involves activities that may be both enriching and demanding (Ulich & Wiese, 2011). As mentioned above with regard to single SSM, many more categories are ascribed to volunteering than to paid work. Since voluntary work activity is a unique source of self-esteem and optimism (Jusot, Grignon, & Dourgnon, 2007), we assume that volunteers benefit from this particularly enriching life domain.

4.2 Interactions Between Life Domains and the Role of Volunteering

In principle, life domains can interplay or interact with one another in two opposite ways: The dominant assumption in the research literature on life domain balance is still that different domains are separate and compete, i.e., life domains interfere with one another negatively (Barnett, 1998; Gareis, Barnett, Ertel, & Berkman, 2009). The fact that different life domains are important in one’s life produces conflicts in the sense that it might be difficult to fulfill diverse responsibilities within and between different domain activities (such as between paid work and family or a hobby and paid work). However, growing evidence of a synergy between life domains and salutary effects of an involvement in different life domains has challenged the conflict assumption (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006; Grzywacz & Marks, 2000). It is reasonable that multiple life domains can enrich each other. Note that conflicts and enrichment are not mutually exclusive but mostly co-occur (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). With regard to volunteering – besides the co-occurrence of conflicts and enrichment – we can imagine that enrichment can develop from prior conflict and vice versa. However, there are still only few studies available that incorporate both, the conflict and the enrichment perspective, not even to mention longitudinal designs to test this assumption. It seems that merging this assumption with the aforementioned functions that volunteering can serve for different individuals (Clary & Snyder, 1999) might be worthwhile. We therefore assume that there are not only inter-individual differences with regard to the functions that voluntary activities can serve but also consider possible intraindividual differences. These functions might change over individuals’ life spans, depending on personal values, characteristics of the environment such as norms imposed by close peers and family, structural characteristics, and so on.

4.3 Conflicts Between Life Domains

Based on a scarcity hypothesis, which assumes that people have a fixed amount of time and energy, individuals who participate in multiple roles within different life domains inevitably experience conflicts and stress that detract from their quality of life (Greenhaus & Allen, 2010; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Based on the definition by Greenhaus and Beutell (1985), Westman, Etzion, and Gortler (2004) wrote that a conflict between work and personal life occurs when “demands associated with one domain are incompatible with the demands associated with the other domain” (p. 413). Studies have revealed several work- and health-related correlates of this conflict (commonly a conflict between paid work and family), with the strongest evidence being confirmed for negative effects on work and life satisfaction (Allen et al., 2000; Bonebright, Clay, & Ankenmann, 2000; Judge & Colquitt, 2004; van Rijswijk, Bekker, Rutte, & Croon, 2004).

4.4 Enrichment Between Life Domains

As mentioned above, within the research on the interface, or rather the interaction, of different life domains (primarily paid work and family) there has been a recent shift in perspective from a negative strain to a more positive resource perspective. This also emphasizes the positive aspects of being involved in different roles within different life domains (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006; Hakanen, Peeters, & Perhoniemi, 2011). Greenhaus and Powell (2006) define enrichment as “the extent to which experiences in one role improve the quality of life in the other role” (p. 73), referring to a transfer of resources and positive affect from one role to the other role (Greenhaus & Allen, 2010). Furthermore, in agreement with Wayne, Grzywacz, Carlson, and Kacmar (2007) and Hakanen et al. (2011) we assume that when individuals succeed in generating resources in relevant life domains, enrichment is enhanced, leading to positive outcomes, such as well-being. Several researchers have identified a significant association between enrichment and health (Allis & O’Driscoll, 2008; van Steenbergen, Ellemers, & Mooijaart, 2007).

4.5 The Role of Volunteering

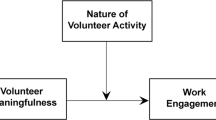

In terms of these possible positive consequences of multiple roles and different tasks and activities within different life domains, volunteering gains relevance because we perceive it as a life domain, which potentially increases the availability of social and psychological resources such as social support, self-efficacy or self-esteem (Mojza & Sonnentag, 2010; Musick & Wilson, 2003). As research showed, these resources can be directly transferred from one domain to another (Greenhaus & Allen, 2010; Rozario, Morrow-Howell, & Hinterlong, 2004). In this sense, volunteering might enrich other life domains and therefore beneficially affect well-being and health. In addition to this assumed direct positive effect on health, we argue that a person’s voluntary work activity can buffer stressors (such as conflicts) occurring between or within various life domains, such as paid work or family:

First, volunteering can influence the appraisal of stressors in general. Stressors that are perceived as irrelevant have a reduced negative impact on well-being and health (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Voluntarily engaged individuals might appraise potentially stressful events or situations as less relevant for their well-being, which reduces the threat by potential stressors (Mojza & Sonnentag, 2010).

Second, volunteering can build up resources that can not only be directly transferred to other life domains (see above) but also can help people to cope with stressors. People who garner satisfaction, confidence, and esteem from various life domains are better able to cope with stress and conflicts (Mojza & Sonnentag, 2010; Ruderman, Ohlott, Panzer, & King, 2002).

Finally, volunteering can facilitate recovery after expending effort, such as at work. As the Effort-Recovery Model (Meijman & Mulder, 1998) indicates, it is essential to be exposed to conditions that facilitate recovery, such as conditions within or through voluntary work activity. In this way, depleted resources can be restored (Sonnentag & Zijlstra, 2006). The effort that we must devote to the tasks within different life domains, such as work and family, elicit a series of physiological and psychological changes. These changes are not permanent but reversible, provided that this effort can be suspended by recovery. If recovery is hindered, that is, if we undertake nothing to restore our resources, these physiological and psychological changes persist and have adverse (health) effects. The risk of burnout is increased, whereas engagement at work is limited (Mostert, Peeters, & Izel, 2011).

Indeed, Mojza and Sonnentag (2010) found that volunteer work has a potential to buffer stress and aid recovery and may have a compensatory function. Volunteering reduces stress and builds up resources and thus might empower people to manage the different demands and challenges in their relevant life domains (paid work, family, social life, and other domains). This would improve their balancing of these life domains (Brauchli et al., 2012; Golüke, Güntert, & Wehner, 2007).

4.6 Insights from Our Own Research

To investigate this compensatory and beneficial function or potential of volunteering as a resource and buffer of stressors, we recently conducted an exploratory study (Brauchli et al., 2012). We wanted to explore the role of voluntary work activity concerning life domain balance, namely, whether it bears the potential to reduce conflicts among different life domains. The results indicated that volunteering is related to these conflicts in a differentiated way: Conflicts that emerge within the paid work domain are higher, the more frequently a person volunteers. In contrast, conflicts from personal life that interfere in a negative way with a person’s paid work life, are lower among employees who engage in volunteer work. Moreover, a non-linear relationship between conflicts and volunteering was found when these two different forms of conflicts – i.e., conflicts emerging within personal life affecting working life and conflicts emerging within working life affecting personal life – were summarized. Thus, there seems to be an optimum: Employees who volunteer with medium frequency (in our study one to three times a month) experience minimal conflicts among different life domains.

In conclusion, it appears evident that volunteering is usually not an additional stressor but instead can serve as a resource, if performed at an optimum level. Finding the optimum level appears to be decisive with regard to volunteering as a resource in individual lives. To complicate things, one can assume that the optimum level varies inter- and intra-individually, because domain conflicts are not only limited to individual determinants but also to situational and, most importantly, monetary determinants. Since not everybody has equal volunteering opportunities due to socioeconomic status or, in other words, since volunteering is an affluence-related phenomenon that not everyone can afford, there are huge gaps in citizens’ opportunities to become engaged in volunteer work. However, if volunteering is meaningful and indeed has health-promoting potential despite the fact that or even because it is unpaid, it seems necessary to consider ways to promote volunteering or meaningful, intrinsically motivated activities. These conclusions are relevant with regard to the final section below, which deals with the utopian ideal of a basic income and how this ideal might promote both meaningful activities and public health.

5 A Basic Income as an Institutional Framework to Promote Public Health?

Historically, the concept of a basic income, or guaranteed income, as discussed by Milton Friedman (1962) and Erich Fromm (1966),Footnote 4 is linked to ideals of justice regarding basic rights that date back to ancient scholars, such as Aristotle (Aristoteles, 1991) as well as more contemporary philosophers (e.g., Rawls, 1975). Aristotle’s idea of common justice refers to all citizens partaking in wealth and moves beyond national spheres toward a global concept of justice (Opielka, Müller, Kreft, & Bendixen, 2009). Today, the Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN) defines a basic income as “an income unconditionally granted to all on an individual basis, without means test or work requirement” (Basic Income Earth Network [BIEN], 2011, p. 1). Currently, civilizing the economy to enable the proliferation of civic freedom and emancipatory social policy would encompass social rights of safety and partaking (Mastronardi & von Cranach, 2010). According to the authors, these rights could be implemented by introducing a basic income. This raises the question as to how a basic income might potentially have positive effects on individuals and society as a whole.

In this final section, we abstain from claiming historical and theoretical completeness in our dealing with the concept of a basic income. As a matter of fact, currently there is no such thing as the concept of basic income, as there are, for example in Germany, numerous differing models that are being discussed politically and economically (Opielka et al., 2009). Although the macro- and microeconomics of a basic income are surely essential in the discussion of its feasibility, we leave these issues unaddressed. Instead, we briefly discuss issues of motivation by referring to empirical results and conclusions stated above. Our aim is to address the question as to whether people would work and experience meaning if they received a guaranteed income without any form of means testing. Additionally, and jointly, we conclude by discussing the health-promoting potential of this utopian concept.

5.1 The Issue of Motivation

The assumption that most people would not work if they received a guaranteed basic income is ubiquitous. And it is often stated in social discourse on the effects of its implementation. That is, it seems commonly held that individuals are primarily driven by extrinsic factors such as remuneration. This idea of people as restricted, resourceful, expecting, evaluating, and maximizing by nature, which for decades has been taken for granted and maintained unchallenged by behavioral economics is recently being called into question more and more by different economists (e.g., Fehr & Fischbacher, 2002; Vanberg, 2008). In Friedman’s (1962) early theorizing, he assumed that a basic income – like any measure against poverty – lowers the drive of individuals receiving the security measure to help themselves but does not exclude this drive. Hence, even from an economic viewpoint, there seems to be something beyond a mere tit-for-tat strategy in humans when it comes to paid work. Other needs besides the existential necessity to make a living appear to deserve attention. Ascribing gainful employment and the income resulting from it the same need-fulfilling potential compared to voluntary work seems at least questionable when taking into account the empirical evidence from research on work-related attitudes, intrinsic motivation, and volunteering. The Kelly Global Workforce Index (Kelly Services, 2009), which surveyed 100,000 participants in 34 countries, showed that in Germany and Switzerland more than 50 % of respondents would forego status and accept cuts in salary to be supplied with more meaningful tasks. In their self-determination theory, Deci and Ryan (2000) stressed growth-oriented activity, maintaining that people are “naturally inclined to act on their inner and outer environments, engage activities that interest them … move toward personal and interpersonal coherence” and that they “do not have to be pushed or prodded to act” (p. 230). Finally, it was shown that the need for meaningfulness is stronger in volunteering than in gainful employment (Wehner et al., 2006) and that more attributes are ascribed to volunteering than to paid work (Mösken et al., 2010). The latter shows the multifaceted diversity of facets of meaning that are inherent to volunteering. All in all, it seems that people’s attitudes toward a basic income are influenced more by their ideas about the nature of human beings and not so much by proven facts from research on motivation.

5.2 The Indirect Health-Promoting Potential of a Basic Income

Today we know of the strain potentials in work and are now gradually starting to explore resources inherent to work and its design by turning to such concepts as meaning or work engagement. Further, psychological studies showed decades ago that unemployment has negative effects on health (Frese & Mohr, 1978; Jahoda, Lazarsfeld, & Zeisel, 1960). As we argued above, I-O psychology was built mainly around the examination of paid labor contexts. This lack of emancipation of other forms of work, one might argue, is rooted in a patriarchal understanding of public, economic labor (Taylor, 2004). The notion that “self-respect and social standing in developed societies are primarily distributed via paid employment” (Merkel, 2009, p. 47) and the fact that community life is collapsing (Putnam, 2000) leads to the following conclusion: Identity and social inclusion of employees in the Western industrialized world are built on a fragile foundation, namely, paid labor. As long as gainful employment remains a central building block of material reproduction and social security, motivational issues will remain linked to paid labor, although there is no initial ontological connection (Heinze & Keupp, 1997). However, it seems questionable whether our current understanding of gainful employment as the main source of identity and of social inclusion will suffice, if individuals are to remain healthy. To illustrate, many people work in different jobs, and boundaries between life domains are becoming more and more permeable. The availability and accessibility of a remote workforce through modern communication technology leads to a drift of business into private life or to an overlap of life domains, respectively. Some European researchers refer to this phenomenon as the subjectification of work (see Moldaschl & Voß, 2003).

Fromm (1966) discussed the psychological implications of a basic income. Fromm viewed the elimination of existential fear, on the basis of personal freedom, as one crucial outcome. From his perspective, freedom in the sense of an independence from material goods is one of the most important personal resources. A decisive link between personal and social resources is the ability to accept, establish, and maintain trusting and helpful relations (Udris, 2006). Thus, trustful social relations outside paid work can bear a certain bridging potential. No man is an island, a phrase borrowed from John Donne and nowadays often used by positive psychologists, points to the importance of relatedness in societies deemed happy and healthy (see Keyes & Haidt, 2003). If we assume that the introduction of a basic income would entail perceptions of equality in society, health effects should occur at least indirectly. Empirical data from political science research suggests that one of the prime movers of social trust is income equality (Uslaner, 2002). According to Uslaner (2002) trust diminishes in an unequal world. At the same time, trust has significant effects on cooperation (Putnam, 2000; Uslaner, 2002). Besides the positive effects of trust on behavioral and health outcomes in the work setting (Kramer & Cook, 2004), different studies have shown that trust is an antecedent of public health (Barefoot et al., 1998). To summarize, the social impact of a basic income on health is, hypothetically stated, indirect and should be mediated by trust and cooperation, the latter of which can take many forms, such as volunteering.

6 Conclusion

We argued theoretically, and to a certain extent empirically, that volunteering bears the potential to serve as a resource in life and in relation to paid work. However, with job uncertainty caused by factors such as precarious working conditions, flexible working hours, and so on, which are present in most societies of today’s globalized world, the potential of meaning-making in volunteering seems like a luxurious accessory that not everybody can afford. For certain underprivileged individuals who work multiple jobs, the idea of volunteering might seem absurd. The same would apply to individuals who are unemployed. Therefore, if we hold that volunteering and its different activities, such as social sector volunteering, cause-related voluntary activism, or modern forms like online volunteering, do indeed have positive spillover effects on health due to the meaning that they contain, then it should become a part of public health policy to further promote these activities. As initial empirical findings suggest, importance should be attached to identifying the right level of volunteering for individuals. Taking the idea of promoting volunteering or unpaid work to the next emancipatory level would imply reconsidering institutional and social policy frameworks. In this respect, the decoupling of work from income could be achieved by introducing a basic income. If this were the case, occupational health policy would go public and a huge and drastic shift from means testing social policy to a trust-based, autonomy-supportive society might take place.

Notes

- 1.

The satisfaction scale consists of items developed in our research group and in connection with several prior investigations on volunteering as well as items adapted from the Schaufeli and Bakker (2003) Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. The Eigen value criterion suggested one general factor solution with an internal consistency of α = .83 after eliminating two items.

- 2.

For a further explanation of the theory and method, see Fransella, Bell, and Bannister (2003).

- 3.

Altogether, the set of elements contained on average ten activities, which were presented to the respondents.

- 4.

Erich Fromm uses the term guaranteed income.

References

Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E. L., Bruck, C. S., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 278–308.

Allis, P., & O‘Driscoll, M. (2008). Positive effects of nonwork-to-work facilitation on well-being at work family and personal domains. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 23, 273–291.

Antonovsky, A., & Franke, A. (1997). Salutogenese zur Entmystifizierung der Gesundheit. Tübingen, Germany: DGVT.

Aristoteles. (1991). Die Nikomachische Ethik [Nicomachean ethics]. Munich, Germany: dtv.

Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work and Stress, 22, 187–200.

Barefoot, J. C., Maynard, K. E., Beckham, J. C., Brummett, B. H., Hooker, K., & Siegler, I. C. (1998). Trust, health, and longevity. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21, 517–526.

Barnett, R. C. (1998). Toward a review and reconceptualization of the work/family literature. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 124, 219–225.

BIEN. (2011). About basic income. Retrieved from http://www.basicincome.org/bien/aboutbasicincome.html

Bonebright, C. A., Clay, D. L., & Ankenmann, R. D. (2000). The relationship of workaholism with work-life conflict, life satisfaction, and purpose in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47, 469–477.

Brauchli, R., Hämmig, O., Güntert, S. T., Bauer, G. F., & Wehner, T. (2012). Vereinbarkeit von Erwerbsarbeit und Privatleben: Freiwilligentätigkeit als psychosoziale Ressource? [Combining paid work and personal life: Volunteering as a psychosocial resource?]. Zeitschrift für Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie, 56, 24–36.

Burke, R. J. (2000). Do managerial men benefit from organizational values supporting work-personal life balance? Women in Management Review, 15, 81–87.

Busch, C., Roscher, S., Kalytta, T., & Ducki, A. (2009). Stressmanagement für Teams in Service, Gewerbe und Produktion – ein ressourcenorientiertes Trainingsmanual [Stress management for teams in service, business, and production: A resource-oriented training manual]. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Cherns, A. (1976). Principles of sociotechnical systems design. Human Relations, 29, 783–792.

Clary, E. G., & Snyder, M. (1999). The motivations to volunteer: Theoretical and practical considerations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8, 156–159.

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R. D., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen, J., et al. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1516–1530.

Claxton, R. P. R., Catalan, J., & Burgess, A. P. (1998). Psychological distress and burnout among buddies: Demographic, situational and motivational factors. AIDS Care, 10, 175–190.

Claxton-Oldfield, S., & Claxton-Oldfield, J. (2007). The impact of volunteering in hospice palliative care. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 24, 259–263.

Cox, T., Taris, T. W., & Nielsen, K. (2010). Organizational interventions: Issues and challenges. Work and Stress, 24, 217–218.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

Emery, F. E., & Emery, M. (1974). Participative design: Work and community life. Canberra, Australia: Center for Continuing Education.

Emery, F. E., & Thorsrud, E. (1976). Democracy at work. A report of the Norwegian Industrial Democracy Program. Leiden, Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff.

Emery, F. E., & Thorsrud, E. (1982). Industrielle Demokratie: Bericht über das norwegische Programm der industriellen Demokratie [Industrial democracy: Report on the Norwegian Industrial Democracy Program]. Bern, Switzerland: Huber.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2002). Why social preferences matter: The impact of non-selfish motives on competition, cooperation and incentives. The Economic Journal, 112, C1–C33.

Field, D., & Johnson, I. (1993). Satisfaction and change: A survey of volunteers in a hospice organisation. Social Science & Medicine, 36, 1625–1633.

Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning. New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

Fransella, F., Bell, R., & Bannister, D. (2003). A manual for repertory grid technique. Chichester, England: Wiley.

Frese, M., & Mohr, G. (1978). Die psychopathologischen Folgen des Entzugs von Arbeit: Der Fall Arbeitslosigkeit [The psychopathological consequences of the loss of work: The case of employment]. In M. Frese, S. Greif, & N. Semmer (Eds.), Industrielle Psychopathologie: Schriften zur Arbeitspsychologie (pp. 282–338). Bern, Switzerland: Huber.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Fromm, E. (1966). The psychological aspects of the guaranteed income. In R. Theobald (Ed.), The guaranteed income: Next step in economic evolution? (pp. 175–184). New York, NY: Doubleday.

Fromm, M. (1995). Repertory Grid Methodik ein Lehrbuch [Repertory grid method: A textbook]. Weinheim, Germany: Deutscher Studien Verlag.

Ganster, D. C., & Schaubroeck, J. (1991). Work stress and employee health. Journal of Management, 17, 235–271.

Gareis, K. C., Barnett, R. C., Ertel, K. A., & Berkman, L. F. (2009). Work-family enrichment and conflict: Additive effects, buffering, or balance? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 71, 696–707.

Golüke, C., Güntert, S., & Wehner, T. (2007). Frei-gemeinnützige Tätigkeit als Ressource für psychosoziale Gesundheit – dargestellt an einer Studie im Hospizbereich [Voluntary activity as a resource for psychosocial health: Shown in a study in the hospice sector]. In S. P. Richter, R. Rau, & S. Mühlpfordt (Eds.), Arbeit und Gesundheit (pp. 343–365). Lengerich, Germany: Pabst Science Publishers.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Allen, T. D. (2010). Work-family balance: A review and extension of the literature. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (2nd ed., pp. 165–183). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10, 76–88.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31, 72–92.

Grzywacz, J. G., & Marks, N. F. (2000). Reconceptualizing the work-family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 111–126.

Guest, D. E. (2004). The psychology of the employment relationship: An analysis based on the psychological contract. Applied Psychology, 53(4), 541–555.

Guinan, J. J., & McCallum, L. W. (1991). Stressors and rewards of being an AIDS emotional support volunteer: A scale for use by care-givers for people with AIDS. AIDS Care, 3, 137–150.

Guion, R. M. (1965). Industrial psychology as an academic discipline. American Psychologist, 20, 815–821.

Güntert, S., Barry, C., & Wehner, T. (2010). The influence of resources, stressors and job characteristics on burnout and satisfaction in voluntary hospice work. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Management, Technology, and Economics, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich, Switzerland.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(2), 159–170.

Hakanen, J. J., Peeters, M. C. W., & Perhoniemi, R. (2011). Enrichment processes and gain spirals at work and at home: A 3-year cross-lagged panel study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84, 8–30.

Heinze, R., & Keupp, H. (1997). Gesellschaftliche Bedeutung von Tätigkeiten ausserhalb der Erwerbsarbeit. Gutachten für die “Kommission für Zukunftsfragen” der Freistaaten Bayern und Sachsen [Societal importance of activities outside gainful employment: Expert’s report for the Kommission für Zukunftsfragen of the Free States of Bavaria and Saxony]. Munich, Germany: Institut für Praxisforschung und Projektberatung.

Ho, Y.-Y., & Yuen, S.-p. (2010). Reconstitution of social work: Towards a moral conception of social work practice. Singapore: World Scientific.

Jahoda, M., Lazarsfeld, P. F., & Zeisel, H. (1960). Die Arbeitslosen von Marienthal: ein soziographischer Versuch mit einem Anhang zur Geschichte der Soziographie [Marienthal: The sociography of an unemployed community](2nd ed.). Allensbach, Germany: Verlag für Demoskopie.

Jones, F., Burke, R. J., & Westman, M. (2006). Work-life balance: Key issues. In F. Jones, R. J. Burke, & M. Westman (Eds.), Work-life balance: A psychological perspective. Hove, England: Psychology Press.

Judge, T. A., & Colquitt, J. A. (2004). Organizational justice and stress: The mediating role of work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 395–404.

Jusot, F., Grignon, M., & Dourgnon, P. (2007). Psychosocial resources and social health inequalities in France: Exploratory findings from a general population survey. Paris, France: IRDES - Institut de recherche et documentation en économie de la sante.

Kelly, G. A. (1986). Die Psychologie der persönlichen Konstrukte [Psychology of personal constructs]. Paderborn, Germany: Junfermann-Verlag.

Kelly Services. (2009). Kelly Global workforce index. Retrieved from http://media.marketwire.com/attachments/EZIR/562/549221_value_of_work.pdf

Keyes, C., & Haidt, J. (2003). Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Kramer, R. M., & Cook, K. S. (2004). Trust and distrust in organizations dilemmas and approaches. New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer.

Llorens, S., Schaufeli, W., Bakker, A., & Salanova, M. (2007). Does a positive gain spiral of resources, efficacy beliefs and engagement exist? Computers in Human Behavior, 23, 825–841.

Macik-Frey, M., Quick, J. C., & Nelson, D. L. (2007). Advances in occupational health: From a stressful beginning to a positive future. Journal of Management, 33, 809–840.

Mastronardi, P., & von Cranach, M. (2010). Lernen aus der Krise [Learning from crisis]. Bern, Switzerland: Haupt Verlag.

Meijman, T. F., & Mulder, G. (1998). Psychological aspects of workload. In P. J. Drenth, H. Thierry, & C. J. De Wolff (Eds.), Handbook of work and organizational psychology (pp. 5–33). Hove, England: Erlbaum.

Merkel, W. (2009). Towards a renewed concept of social justice. In O. Cramme & P. Diamond (Eds.), Social justice in the global age (pp. 38–58). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Mojza, E. J., & Sonnentag, S. (2010). Does volunteer work during leisure time buffer negative effects of job stressors? A diary study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 19, 231–252.

Moldaschl, M., & Voß, G. G. (2003). Subjektivierung von Arbeit [Subjectification of work]. Munich, Germany: Rainer Hampp Verlag.

Morf, M. E., & Weber, W. G. (2000). I/O psychology and the bridging potential of A. N. Leont’ev’s activity theory. Canadian Psychology-Psychologie Canadienne, 41, 81–93.

Mösken, G., Dick, M., & Wehner, T. (2010). Wie frei-gemeinnützig tätige Personen unterschiedliche Arbeitsformen erleben und bewerten: Eine narrative Grid-Studie als Beitrag zur erweiterten Arbeitsforschung [How persons doing volunteer work perceive and rate different forms of work: A narrative grid study as a contribution to expanded work research]. Arbeit, 19, 37–52.

Mostert, K., Peeters, M. C. W., & Izel, R. (2011). Work-home interference and the relationship with job characteristics and well-being: A South-African study among employees in the construction industry. Stress and Health, 27, 238–251.

Musick, M. A., & Wilson, J. (2003). Volunteering and depression: The role of psychological and social resources in different age groups. Social Science & Medicine, 56, 259–269.

Myers, D. G. (2000). The American paradox spiritual hunger in an age of plenty. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2003). The construction of meaning through vital engagement. In C. Keyes & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived (pp. 83–104). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Opielka, M., Müller, M., Kreft, J., & Bendixen, T. (2009). Grundeinkommen und Werteorientierungen Eine empirische Analyse [Basic income and value orientations: An empirical analysis]. Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften/GWV Fachverlage GmbH.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Rawls, J. (1975). Eine Theorie der Gerechtigkeit [A theory of justice]. Frankfurt, Germany: Suhrkamp.

Resch, M., & Bamberg, E. (2005). Work-Life-Balance - Ein neuer Blick auf die Vereinbarkeit von Berufs- und Privatleben? [Work-life balance: A new perspective of the combination of work and private life]. Zeitschrift für Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie, 49, 171–175.

Rice, A. K. (1958). Productivity and social organization: The Ahmedabad experiment, technical innovation, work organization and management. Oxford, England: Tavistock.

Rimann, M., & Udris, I. (1997). Subjektive Arbeitsanalyse: der Fragebogen SALSA [Subjective work analysis: The SALSA questionnaire]. In O. Strohm & E. Ulich (Eds.), Unternehmen arbeitspsychologisch bewerten (pp. 281–298). Zurich, Switzerland: vdf Hochschulverlag.

Ross, M. W., Greenfield, S. A., & Bennett, L. (1999). Predictors of dropout and burnout in AIDS volunteers: A longitudinal study. Aids Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/Hiv, 11, 723–731.

Rozario, P. A., Morrow-Howell, N., & Hinterlong, J. E. (2004). Role enhancement or role strain: Assessing the impact of multiple productive roles on older caregiver well-being. Research on Aging, 26, 413–428.

Ruderman, M. N., Ohlott, P. J., Panzer, K., & King, S. N. (2002). Benefits of multiple roles for managerial women. Academy of Management Journal, 45(2), 369–386.

Sauer, D. (2011). Von der “Humanisierung der Arbeit” zur “Guten Arbeit” [From “humanization of work” to “good work”]. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 15, 18–24.

Schaubroeck, J., Ganster, D. C., & Fox, M. L. (1992). Dispositional affect and work-related stress. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 322–335.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2003). The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES). Unpublished manuscript, Department of Social & Organizational Psychology, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 293–315.

Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2009). Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Development International, 14, 204–220.

Schein, E. H. (1980). Organizational psychology (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5–14.

Sonnentag, S., & Zijlstra, F. R. H. (2006). Job characteristics and off-job activities as predictors of need for recovery, well-being, and fatigue. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 330–350.

Spector, P. E., Zapf, D., Chen, P. Y., & Frese, M. (2000). Why negative affectivity should not be controlled in job stress research: Don’t throw out the baby with the bath water. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 79–95.

Taylor, R. F. (2004). Extending conceptual boundaries: Work, voluntary work and employment. Work, Employment & Society, 18, 29–49.

Trist, E. L. (1981). The sociotechnical perspective: The evolution of sociotechnical systems. Issues in the Quality of Working Life, Occasional Papers No. 2. Toronto, Canada: Ontario Quality of Working Life Centre.

Trist, E. L., & Bamforth, K. W. (1951). Some social and psychological consequences of the Longwall method of coal-getting. Human Relations, 4, 3–38.

Udris, I. (2006). Salutogenese in der arbeit - ein paradigmenwechsel? [Salutogenesis in work: A paradigm shift?]. Wirtschaftspsychologie, 8, 4–14.

Udris, I., & Alioth, A. (1980). Fragebogen zur “subjektiven Arbeitsanalyse” (SAA) [Questionnaire on “subjective work analysis” (SAA)]. In E. Martin, I. Udris, U. Ackermann & K. Oegerli (Eds.), Schriften zur Arbeitspsychologie: Vol. 29. Monotonie in der Industrie (pp. 61–68 and 204–207). Bern, Switzerland: Huber.

Udris, I., & Rimann, M. (1999). SAA und SALSA: Zwei Fragebögen zur subjektiven Arbeitsanalyse [SAA and SALSA: Two questionnaires on subjective work analysis]. In H. Dunckel (Ed.), Handbuch psychologischer Arbeitsanalyseverfahren (pp. 397–419). Zurich, Switzerland: vdf Hochschulverlag.

Ulich, E. (2005). Arbeitspsychologie [Work psychology]. Zurich, Switzerland: vdf Hochschulverlag.

Ulich, E., & Wiese, B. S. (2011). Life domain balance – Konzepte zur Verbesserung der Lebensqualität [Life domain balance: Concepts to improve the quality of life]. Wiesbaden, Germany: Gabler Verlag.

Uslaner, E. (2002). The moral foundations of trust. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

van Rijswijk, K., Bekker, M. H. J., Rutte, C. G., & Croon, M. A. (2004). The relationships among part-time work, work-family interference, and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9, 286–295.

van Steenbergen, E. F., Ellemers, N., & Mooijaart, A. (2007). How work and family can facilitate each other: Distinct types of work-family facilitation and outcomes for women and men. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12, 279–300.

Vanberg, V. J. (2008). On the economics of moral preferences. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 67, 605–628.

Wayne, J. H., Grzywacz, J. G., Carlson, D. S., & Kacmar, K. M. (2007). Work-family facilitation: A theoretical explanation and model of primary antecedents and consequences. Human Resource Management Review, 17, 63–76.

Westman, M., Etzion, D., & Gortler, E. (2004). The work–family interface and burnout. International Journal of Stress Management, 11, 413–428.

Wehner, T., Mieg, H., & Güntert, S. (2006). Frei-gemeinnützige Arbeit [Volunteer work]. In S. Mühlpfordt & P. Richter (Eds.), Ehrenamt und Erwerbsarbeit (pp. 19–39). Munich, Germany: Hampp.

Wiese, B. (2007). Work-life balance. In K. Moser (Ed.), Lehrbuch der Wirtschaftspsychologie (pp. 245–263). Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Jiranek, P., Brauchli, R., Wehner, T. (2014). Beyond Paid Work: Voluntary Work and its Salutogenic Implications for Society. In: Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5640-3_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5640-3_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-5639-7

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-5640-3

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)