Abstract

Self-reported health, a widely used measure of general health status in population studies, can be affected by certain demographic variables such as gender, race/ethnicity and education. This cross-sectional assessment of the current health status of older adult residents was conducted in an inner-city Houston neighborhood in May, 2007. A survey instrument, with questions on chronic disease prevalence, health limitations/functional status, self-reported subjective health status in addition to demographic data on households was administered to a systematic random sample of residents. Older adults (>60 years of age) were interviewed (weighted N = 127) at their homes by trained interviewers. The results indicated that these residents, with low literacy levels, low household income and a high prevalence of frequently reported chronic diseases (hypertension, diabetes and arthritis) also reported non-participation in community activities, volunteerism and activities centered on organized religion, thus, potentially placing them at risk for social isolation. Women reported poorer self-reported health and appeared to fare worse in all health limitation indicators and reported greater structural barriers in involvement with their community. Blacks reported worse health outcomes on all indicators than other sub-groups, an indication that skills training in chronic disease self-management and in actively eliciting support from various sources may be beneficial for this group. Therefore, the use of self-reported health with a broad brush as an indicator of “true” population health status is not advisable. Sufficient consideration should be given to the racial/ethnic and gender differences and these should be accounted for.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has strongly recommended development of evidence-based, community focused strategies to alleviate the disproportionate burden of illness on minorities [1]. Minority older adults face added challenges in maintaining their health. The National Institute on Aging recommends provision of social support and continued involvement in activities to foster positive effects on health and longevity in older adults. Similarly, [2] describe successful aging as a low probability of disease, high level of functioning and active engagement with life. Scientists and lay persons have long acknowledged the central role of social relationships and involvement in activities to promote better health outcomes [3]. Being part of an active network provides more opportunities for participation in other activities, both of leisure and productive nature. Volunteerism in older adults is also associated with positive health outcomes [4, 5]. Although many older adults report perceived restrictions in participating in community activities, [6, 7] reported that social and productive activities that involve little or no enhancement of fitness lower the risk of all cause mortality as much as fitness activities do. Such activities foster feelings of being independent, engaged, useful and productive, which are consistently associated with positive health outcomes [8–11].

Self-reported health (SRH), a self-reported global assessment of perceived health, is an independent and strong predictor of mortality and morbidity [12], in addition to being a useful indicator of a population’s overall well being [13, 14]. Poorer health status has been found to be associated with both lower education and income levels in minority communities [15, 16]. Prospective studies have found consistent associations between SRH and future morbidity and mortality. Socio-economic status (SES) is strongly associated with self-rated health [17] for most studies. This global subjective health rating of SRH has been measured by other researchers on a 3–5 point likert-type scale in population health studies, ranging from “excellent” to “poor” and is more inclusive than current physical status, encompassing assessments of health behaviors, psychological well-being trajectories in health over time and social well-being [12, 18]. As an estimate of population health, this measure may be as effective an indicator as collecting extensive biological data, in addition to being far more feasible.

However, SRH evaluation is influenced by context and the meaning of ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ health, is subject to various interpretations [12] and it is still not clear how far these measures correspond to the “real” (objective) health status. Much debate is still ongoing about gender differences, age differences, race/ethnicity differences and SES differences in SRH [12, 19], and whether these associations are constant over time [20, 21]. More recently, SRH has been researched in developing countries and also among other minority groups in the US. It appears that even across cultures, SRH is associated with health outcomes. Civic engagement, measured by membership in clubs and other civic groups, in a study done in Jordan, was found to have an independent association with SRH, after controlling for demographic variables and health risk factors, [22, 23] reported that a higher proportion of women reported poorer SRH in Syria than seen in other studies from developing countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh. The women in this Syrian study reported poor SRH far more frequently than men—a finding that the authors tentatively attribute to strong gender roles and cultural norms. A state-wide study on Vietnamese adults in California [24], with data from the California Health Interview Survey, reports that older Vietnamese adults are at risk for mental health conditions and report poorer self-reported health.

Objective

-

1.

To assess the perceived health status, functional status, civic/community participation and chronic disease prevalence in older adults in an inner-city neighborhood in Houston.

-

2.

To determine the association of functional status, chronic disease and civic participation with SRH.

-

3.

To determine the role of education and gender in the association of functional status, chronic disease and civic participation with SRH.

Methods

A community-based research project was initiated by Houston Department of Health and Human Services (HDHHS) in a neighborhood defined by contiguous census blocks along the Houston Ship Channel. This neighborhood adjoins the Port of Houston which includes more than 150 industrial facilities, primarily petro-chemical refineries in Houston, Texas. Community mobilization was initiated by a citizen’s environmental coalition group concerned about environmental pollutants. HDHHS continued to nurture, develop and build on this initial mobilization effort in partnership with the residents and community coalition groups of this inner-city neighborhood, with an emphasis on health.

A survey instrument was designed with feedback from the local Area Agency on Aging (AAA) to gather information on the health status of older adults in this neighborhood. The AAA has senior assistance programs in place for the County, with some services being offered by external partners and contractors. AAA provides assistance with prescription medication as well as, hearing, vision and dental screening. External partners and contractors provided services such as meal delivery programs, health promotion programs and in-home respite care. Our survey, conducted in September 2007, consisted of a sample of 308 households; children <5 year old and adults ≥60 year old composed of 9.4 and 13.5%, respectively, of the sample. This was comparable to census 2000 population distribution of the neighborhood area (9.5% children <5 year old, and 11.1% adult ≥60 year old). Since the primary purpose of the survey was for public benefit and to inform and improve public service programs, the study was deemed IRB exempt. A total of 127 community dwelling older adults (≥60 years of age) were administered the survey instrument after consent to participate was noted by trained surveyors. Assurances of confidentiality were made and the interview lasted 15 minutes, after which the participant received a comprehensive package of information on services and resources available in their area. Systematic sampling was conducted in randomly selected clusters of census blocks in the inner-city neighborhood, following the World Health Organization’s EPI method [25], resulting in a representative sample of older adults in this community.

Survey Instrument Questions

-

1.

Self-reported health was assessed by “How would you rate your current health?”

-

2.

Participation in community-based senior activities (civic participation) was determined by “Do you participate in activities and programs in your area that are available to seniors such as civic clubs, volunteering in schools or hospitals, senior volunteer programs or church programs?

-

3.

Prevalence of chronic disease was assessed by self-reported, doctor-diagnosed chronic conditions such as diabetes, asthma, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease/stroke, arthritis or rheumatic disease, and cancer. This manuscript reports on the three chronic conditions that were most prevalent among the participants.

-

4.

Finally, data on quality of life due to health limitations, health problems affecting day to day activities and self-management of health conditions were assessed by the following questions on a 5-point Likert scale. These are identical to the question asked on Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).

-

(a)

In the past month, how often has your physical health interfered with your job or normal social activities, hobbies, household chores, and/or errands?

-

(b)

How confident are you that you can:

-

(i)

Keep health problems from interfering with your day to day routine?

-

(ii)

Manage your health condition and decrease your need to see a doctor?

-

(i)

-

(a)

Analytic Strategies

Data was managed and analyzed by using SPSS version 15. Descriptive statistics comprised percentages or proportions to measure categorical and dichotomous data and means or medians to measure continuous data. Various statistical tests were applied to test the difference among outcomes. Chi-square tests were used to compare proportions and independent sample T tests were used to compare means. Multivariate regression models using both logistic and linear regression, were applied for testing the association between predictors and outcomes after adjusting for the potential demographic confounders.

Results

The results of our analysis are presented in the following order. First, the demographic profile of older adults will be presented followed by the description of the extent of participation in community-based activities by living arrangements (Table 1). Next, the perceived effects of health limitations (Table 2) will be presented by gender. Finally, the prevalence of chronic health conditions, participation in community activities and perceived health limitations by race/ethnicity (Table 3) and self-rated health will be presented (Table 4). Additional logistic regression analysis examining the relationships between the variables of interest will be presented (Table 5), followed by the same analysis after adjustment for potential confounders such as education level and gender (Table 6).

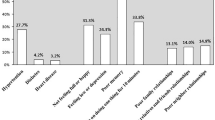

Slightly more than half (51.2%) of the older adults in the neighborhood reported being black and also being primarily Spanish-speaking (53.3%). A large proportion (60.6%) had low levels of education (less than 8th grade) and only a quarter (24.4%) of this group had a high school diploma; most of them did not have full time employment (87.4%), and were not in the workforce. Almost a third (33.1%) reported being homemakers. The survey sample had 56 (44.1%) males and 71 (55.9%) females. Of the total weighted N = 127, 17 lived alone (13.4%). Older adults, as a whole, also reported low participation in the community based senior activities (civic participation) listed. In addition, nearly half (44.8%) of this sample reported barriers in not participating in activities as being due to health related reasons.

Older women reported more health-related barriers to participation in community-based senior activities (52.9%) when compared to older men (36.4%). Older men, on the other hand, reported greater lack of interest in participation (42.4%) than older women (29.4%). Of our sample, older women, more frequently than men, reported that their perceived health limitations were a problem (Table 2). Older women reported that their physical health interferes with their daily activities (OR = 2.27, P = .048, 95% CI = 1.0–4.8); they were not confident that they could keep health problems from interfering with their daily activities (OR = 4.53, P = .011, 95% CI = 1.36–13.68); and were not confident about managing their health well enough to avoid seeing a doctor (OR = 2.54, P = .057, 95% CI = 0.96–6.49) (Table 2).

Our sub-sample of older adults living alone is small. Although the proportion of some chronic disease prevalence and health limitations of older adults that live alone compared to those that live with someone are much greater, the small sample size of older adults that live alone constrains us from exploring this issue in further detail.

When race/ethnic differences in self-rated health were examined (Table 3), approximately half of white and black older adults reported good health vs. fair or poor health. However, two-thirds of the Hispanic adults reported being in good health (although the number of older adults belonging to this group was small). Blacks reported higher prevalence of chronic conditions and far greater perceived health limitations. Low levels of volunteerism and civic participation were observed in all groups. Blacks reported lower participation in civic/community activities but higher levels of participation in activities centered in/around religious organizations.

There did not appear to be a marked difference among males and females as far as self reported health (Table 4). However, older women reported far greater perceived health limitations (40.6 vs. 23.6%) than older men. Older women also reported far greater prevalence of chronic conditions such as arthritis (46.4 vs. 30.4%), hypertension (58.0 vs. 44.6%) and diabetes (35.7 vs. 30.2%) than older men. When examining indicators of community involvement, more than a third (35.2%) of older women reported being involved in activities of religious organizations.

Among those that those that reported fair or poor health (Table 5), were four times (OR = 4.27, P ≤ 0.05) more likely to report physical limitations, almost three times (OR = 2.84, P ≤ 0.05) more likely to report difficulty coping with their health, and less difficulty (OR = 0.40, P ≤ 0.05) managing their health problems; far less likely to volunteer (OR = 0.28, P ≤ 0.1) in the community and less likely to participate in activities of civic/community organizations (OR = 0.28, P ≤ 0.1). Those who perceived their health to be fair or poor were also more than three times (OR = 3.50, P ≤ 0.05) likely to report doctor diagnosed hypertension and twice (OR = 2.21, P ≤ 0.05) as likely to report doctor diagnosed diabetes and almost twice (OR = 1.94, P ≤ 0.1) as likely to report doctor diagnosed arthritis.

When the effect of sex and education was controlled for, of all the indicators examined for perceived health limitations, participation in activities and prevalence of chronic disease (Table 6), perceived physical limitations and prevalence of hypertension appeared to be affected when the effect of gender and education were controlled in logistic regression model. All other associations tend to diminish. It appears that gender and education served to decrease the association between physical limitations and fair/poor health. Conversely, gender and education appears to strengthen the association between reported prevalence of hypertension and fair/poor reported health.

Discussion

Self-reported health is a widely used as a health outcome in epidemiological studies and the association of self-reported health with various health outcomes is extensively documented. Older adults were chosen as a priority group for this community assessment because of the need to understand the health related issues of this burgeoning population and to be better prepared to anticipate and plan future programmatic initiatives for the ageing population. In an effort to assess health at the community level, this study was conducted to learn more about some social and health issues in this community.

Our assessment indicates that, in this neighborhood, a large proportion of older adults did not fare well in terms of their health. It is likely that non-participation in community based senior activities resulting in a smaller number of network ties, also placed them at greater risk for social isolation. Volunteerism in older adults is associated with positive health outcomes [4, 5] and low levels of volunteerism and civic participation in this neighborhood places this population at risk for poorer health outcomes. In addition, with advancing age, the number and severity of chronic conditions is likely to increase. With additional comorbidity comes an increased risk of decline in functional status and poor health outcomes. Racial/ethnic and gender disparities were observed and were striking in some cases. In particular, we found that older women in our sample currently report having several health limitations that stand as barriers to participation in community activities, similar to previous findings by [6] and they also consistently reported poorer self-reported health in large numbers. In addition, this group was vulnerable because of their reported physical limitations, poorer coping abilities and difficulties managing their health conditions.

Therefore, self-rated health, even when measured on a broad 3 point likert-type scale, is a useful and reliable measure of general health status of the community. However, gender and education appear to affect the association between SRH and various health indicators, strengthening some associations and weakening others. Since gender and education levels can affect the relationship between SRH and the other variables, caution should be exercised in using SRH as an indicator of general health status without taking gender, education and race/ethnicity into account, since patterns differ across groups. Others also report that socio-economic status affects the strength of SRH in predicting subsequent mortality [12]. In any case, this issue requires further exploration. More than half of our sample self-identified as black and Hispanic. The minority status and low education and income possibly places them at an even greater risk of poor health outcomes. Additionally, it is interesting to note that in our study, far greater numbers of Hispanic older adults report being in “good” health than black or white older adults. It is not clear whether this is a valid finding or is due to this group’s differential assessment of subjective health status, their acculturation levels or is simply an artifact of our analysis due to the small sample size.

Our small sample size does not permit us to further stratify and analyze our data. However, it provides important information in terms of identifying the needs of “at risk” older minority adults and prioritizing our resources to engage this population and develop skills training programs to reduce their burden of poor health. It is clear from our findings that, inner-city older adults would benefit from skills training in chronic disease self-management programs, and in developing wider social networks and accessing available sources support when needed, so that they may be better equipped to handle day-to-day challenges. Further prospective research is needed in identifying and confirming causal pathways.

References

Jones, D., Franklin, C., Butler, B. T., Williams, P., Wells, K. B., & Rodriguez, M. A. (2006). The building wellness project: A case history of partnership, power sharing and compromise. Ethnicity and Disease, 16, S54–S66.

Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1998). Successful aging. Aging, 5, 142–144.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Brown, S., Nesse, R. M., Vonokur, A. D., & Smith, D. M. (2003). Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: Results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychological Science, 14, 320–327.

Brown, W. M., Consedine, N. S., & Magai, C. (2005). Altruism relates to health in an ethnically diverse sample of older adults. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60, 143–152.

Wilkie, R., Peat, G., Thomas, E., & Croft, P. (2006). The prevalence of person perceived participation restriction in community dwelling older adults. Quality of Life Research, 15, 1471–1479.

Glass, T. A., de Leon, C. M., Marottoli, R. A., & Berkman, L. F. (1999). Population based study of social and productive activities as predictors of survival among elderly Americans. British Medical Journal, 319, 478–483.

Turner, R. J., & Turner, J. B. (1999). Social integration and support. In C. S. Aneshensel & J. C. Phelan (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental Health. New York: Kluwer.

Berkman, L. F. (1995). The role of social relations in health promotion. Psychosomatic Medicine, 57, 245–254.

Berkman, L. F., & Kawachi, I. (2000). A historical framework for social epidemiology. In L. F. Berkman & I. Kawachi (Eds.), Social epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Herzog, A. R., Franks, M. M., Markus, H. R., & Holmberg, D. (1998). Activities and well-being in older adults: Effects of self-concept and educational attainment. Psychology and Aging, 13, 179–185.

Dowd, J. B., & Zajacova, A. (2007). Does the predictive power of self rated health for subsequent mortality risk vary by socioeconomic status in the US? International Journal of Epidemiology, 36, 1214–1221.

Pan, L., Mukhtar, Q., Geiss, S. L., Rivera, M., Alfaro-Correa, A., & Sniegowski, R. (2006). Self-rated fair or poor health among adults with diabetes–United States, 1996–2005. Mortality and Morbidity Weekly, 15, 1224–1227.

Phillips, L. J. Hammock, R. L., & Blanton, J. M. (2005). Predictors of self rated health status among Texas residents. Preventing chronic disease: Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy. Accessed March 15, 2009. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2005/oct/04_0147.htm.

Skarupski, K., de Leon, C., & Bienias, J. (2007). Black White differences in health related quality of life among older adults. Quality of Life Research, 16, 287–296.

Zunker, C., & Cummins, J. (2004). Elderly health disparities on the U.S.–Mexico border. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology, 19, 13–25.

Marra, C. A., Lynd, L. D., Esdaile, J. M., Kopec, J., & Anis, A. H. (2004). The impact of low family income on self reported health outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis within a publicly funded health care environment. Rheumatology, 43, 1390–1397.

Ferraro, K. F., Farmer, M. M., & Wybraniec, J. A. (1997). Health trajectories: Long term dynamics among black and white adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38, 38–54.

Franks, P., Gold, M. R., & Fiscella, K. (2003). Sociodemographics, self rated health, and mortality in the US. Social Science and Medicine, 56, 2505–2514.

Lee, S. J., Moody-Ayers, S. Y., Landefeld, C. S., et al. (2007). The relationship between self-rated health and mortality in older black and white Americans. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55, 1624–1629.

Singh-Manoux, A., Gueguen, A., Martikainen, P., Ferrie, J., Marmot, M., & Shipley, M. (2007). Self-rated health and mortality: Short and long term associations in the Whitehall II study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69, 138–143.

Khawaja, M. Tewtel-Salem, M., & Obeid, M. S. (2006). Civic engagement, gender and self rated health in poor communities: evidence from Jordan’s refugee camp study. Health Sociology Review. Accessed April 20, 2009. Available from: http://www.accessmylibrary.com/coms2/summary_0286-32155221_ITM.

Asfar, T., Ahmad, B., Rastam, S., Mulloli, T. P., Ward, K., & Maziak, W. (2007). Self-rated health and its determinants among adults in Syria: A model from the Middle East. BMC Public Health, 7, 177.

Sorkin, D., Tan, A. L., Hays, R. D., Mangione, C. M., & Ngo-Metzger, Q. (2008). Self-reported health status of vietnamese and non-hispanic white older adults in California. Journal of American Geriatric Society, 56, 1543–1548.

World Health Organization. (1991). Training for mid-level managers: The EPI coverage survey. Geneva: WHO Expanded Programme on Immunization, WHO/EPI/MLM/91.10.

Acknowledgments

This research was not supported by external funding. We would like to acknowledge the support of our staff and colleagues from Houston Department of Health and Human Services, who participated in this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Banerjee, D., Perry, M., Tran, D. et al. Self-reported Health, Functional Status and Chronic Disease in Community Dwelling Older Adults: Untangling the Role of Demographics. J Community Health 35, 135–141 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-009-9208-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-009-9208-y