Abstract

We investigate whether the presence of outside members in the board or buying ad hoc professional advisory services fuel short-term start-up growth. Furthermore, how the founding team’s initial knowledge stock as well as environmental uncertainty affect this relationship is examined. Our results only suggest a positive association between professional advisory services and start-up growth, which seem to suggest that the presence of an outside board member does not affect short-term start-up growth. We also find that the relationship between professional advisory services and growth is more pronounced when previous relevant industry expertise of the founding team is lower and technological opportunities in the environment are larger. Our findings advance understanding of the determinants of short-term start-up growth and are of practical relevance to entrepreneurs and policymakers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The entrepreneurship literature emphasizes the importance of knowledge in fuelling the growth of entrepreneurial firms (Macpherson and Holt 2007; Ratinho et al. 2020). However, start-ups often have a limited knowledge base (Sapienza et al. 2006), and therefore face a so-called knowledge gap (Chrisman et al. 2005; Johnson et al. 2007) between the knowledge needed for successful venturing and that present in the firm. Since considerable time and effort are typically required to acquire knowledge internally, external acquisition will often be most efficient (Chrisman and McMullan 2004; Rubin et al. 2015).

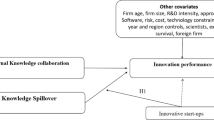

In this study, we focus on the role of professional advisory services (PAS) and outside board members (OBMs) in closing the knowledge gap. PAS providers, such as accountants, bankers, consultants, and lawyers, are hired mainly for one-off tasks that require specific explicit or tacit knowledge that the start-up lacks (Robson and Bennett 2000), whereas OBMs provide advice and counseling, build external legitimacy, and networks (Hillman and Dalziel 2003). The knowledge-based view (KBV) of the firm suggests two key factors that may influence the effectiveness of using external knowledge sources. First, the firm must be able to aggregate, integrate, and apply external knowledge, which depends on prior knowledge and skills present in the firm (Zahra and George 2002). Second, in rapidly changing environments, access to and integration of specialized knowledge is even more important than in more stable environments for firm survival and growth (Grant 1996a).

We contribute to the literature in several ways. First, we advance the entrepreneurship and governance literatures by comparing the performance effects of different external knowledge sources (Vivas and Barge-Gil 2015). Considering two external knowledge sources simultaneously allows us to determine which matters more for firm growth, and may alleviate the potential omitted variable problem present in many previous studies. Furthermore, unlike most previous studies, we consider the diversity rather than intensity of external advisory use (e.g., Chrisman et al. 2005; Cumming and Fischer 2012). Taking a diversity approach allows us to discriminate between the performance effects of focused versus differentiated advisory use. Diversity also better resonates with the view that entrepreneurs must be “jacks-of-all-trades” (Lazear 2004). Second, we contribute to the KBV by showing the importance of alternative sources of external knowledge accumulation and their relationship with the firm’s internal knowledge stock and the level of uncertainty in the external environment. Third, we contribute to the governance literature by showing that the presence of OBMs has no impact on short-term start-up growth, even after testing various conceptualizations and operationalizations and taking into account the internal knowledge context and external environmental uncertainty (Fiegener 2005; Knockaert and Ucbasaran 2013).

2 Theory and hypotheses

As previously mentioned, new firms are confronted with a knowledge gap or knowledge deficit (Chrisman et al. 2005; Johnson et al. 2007). Apart from setting up management systems to accelerate knowledge accumulation internally (Davila et al. 2010), start-ups may fill this knowledge gap by accessing external knowledge. In this study, we consider two important channels through which a start-up may acquire external knowledge: through flexible, ad hoc use of PAS, and through the more permanent solution of appointing outside members to its board.

A multitude of previous studies of the relationship between the use of business advisors and measures of firm performance provide mixed evidence. Several studies report a positive significant effect (e.g., Chrisman and McMullan 2000, 2004), whereas other studies find no significant relationship (e.g., Robson and Bennett 2000). Interestingly, Mole’s (2002) interviews with personal business advisors reveal that accountants’ and solicitors’ advice impacts particularly on SMEs. This suggests that legitimate power rather than institutional trust is crucial to understanding the differential impact, although a difference in the intensity of services provided may also be a contributory factor (Mole et al. 2009). Unfortunately, empirical evidence also fails to identify any consistent and significant positive relationship between OBMs and new venture performance, regardless of how performance is measured (Daily et al. 2002).

With regard to firms’ boards of directors, previous literature shows that they play two main roles: a control role and a service role (Van Den Heuvel et al. 2006). In small and entrepreneurial firms, ownership and control are typically concentrated in the same hands, making agency conflicts between owners and managers less of an issue (Schulze et al. 2003; Uhlaner et al. 2007; Garg 2013)) and the control role less important. However, in small firms, both the entrepreneur and the governance structure affect efficiency. The entrepreneur fulfills a monitoring role and decides whether a continuous shock in a firm’s environment requires a change to the firm’s organizational structure (Casson 1996). Having a founder on the board results in productivity gains in SMEs. As they grow, an increase in board size and an expansion of the management team become more important for realizing scale economies (Cowling and Mitchell 2003). Finally, as well as extending the size of the top management team, having more OBMs has been shown to encourage strategic change in closely held small firms (Brunninge et al. 2007).

The service role of the board, on the other hand, is considered to be more important in small firms (Van Den Heuvel et al. 2006). Through its service role, the board provides the firm with various types of resource, by providing advice and counsel to the management team on strategy and by building external legitimacy and improving relationships with relevant stakeholders (Hillman and Dalziel 2003; Garg and Eisenhardt 2017). OBMs may strengthen the founding team’s human capital by bringing in complementary knowledge and experience (Clarysse et al. 2007; Hillman 2015).

2.1 Influence of PAS and OBMs on short-term start-up growth

PAS and OBMs are both external sources of knowledge that start-ups can use to increase their knowledge stock, thereby contributing to start-up growth. However, we argue that two characteristics of PAS make them likely to be more effective than OBMs: specific relevance and timing. First, the intervention of PAS or OBMs will only be effective if the advisors are well-trained, capable, and experienced (Chrisman and McMullan 2004). Maister et al. (2000) note that PAS firms often encourage an exclusive focus on content expertise and technical mastery, which continue to be pivotal to professional advisors throughout their careers (Dyer and Ross 2007). This strong focus is not only encouraged by employers and employees of PAS firms but is also expected by their clients. Clients approach PAS firms for specific information within the advisor’s area of expertise and demand results to solve immediate problems (Dyer and Ross 2007). In short, PAS providers have the competencies and specialized expertise needed to address specific problems, and firms select them based on their competencies and specialization (Clayton et al. 2018). OBMs, on the other hand, are not necessarily best suited to advise on specific problems. Boards of start-ups are generally quite small (Boone et al. 2007), and will therefore almost inevitably lack certain competencies (Zahra and Pearce 1989). Owing to this specialization difference between OBMs and PAS, we expect advice from PAS to be, on average, more specific and relevant than that of OBMs, and thus more effective in contributing to start-up growth.

Second, the effectiveness of advice also depends on its timing. The potential to internalize learning and transfer it to new situations is greatest when instruction is provided at the moment of most relevance. Bolton (1999) calls this type of learner-driven, on-demand provision of knowledge “just-in-time” (JIT) learning, and Brandenburg and Ellinger (2003) refer to the “time value of learning” in stressing the importance of JIT learning. The “time value of learning” implies that the same knowledge has a different value depending when it is acquired, i.e., too early, just-in-time, or too late (Miner and Mezias 1996). In the context of our study, there is a significant difference between PAS and OBMs in relation to when advice is acquired from these two knowledge sources. PAS can be called in immediately a need is identified by the entrepreneur, whereas OBMs’ advice may not be available until a board meeting takes place, typically only three or four times a year in SMEs (Brunninge et al. 2007). Therefore, we expect advice from PAS to be, on average, more “just-in-time” than that of OBMs, increasing the potential for it to be appropriately aggregated, integrated and applied. Based on these arguments, we formulate our first hypothesis as follows:

-

Hypothesis 1a The use of external knowledge (PAS and OBMs) is positively associated with short-term start-up growth.

-

Hypothesis 1b The effect of PAS is stronger than the effect of OBMs on short-term start-up growth.

2.2 Influence of the firm’s initial knowledge stock on the effectiveness of PAS and OBMs

The KBV suggests that value is created when newly acquired knowledge is assimilated and exploited, such as by combining it with existing knowledge (Grant 1996b). However, entrepreneurs’ absorptive capacity differs, in that they are not all equally able to identify, assimilate, and exploit new knowledge (Cohen and Levinthal 1990). A higher level of prior knowledge and skills facilitates these processes (Zahra and George 2002). Absorptive capacity allows entrepreneurs to recognize valuable elements of new external advice, thereby enhancing its benefits to the firm (Van Doorn et al. 2017). For start-ups, the firm’s initial knowledge stock will thus be a determining factor in its absorptive capacity.

A large part of the start-up’s initial knowledge stock is brought in by its founders at the moment of founding. This consists of the founders’ related pre-start-up knowledge and skills acquired during their previous professional careers. Founders with higher knowledge stocks will be better able to identify relevant knowledge, absorb this knowledge and exploit it effectively. In contrast, less knowledgeable entrepreneurs may overlook the true value of external knowledge and how it can be exploited to increase firm growth. This reasoning leads us to the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 2 The impact of external knowledge on short-term start-up growth is stronger for firms with a higher initial knowledge stock.

2.3 Influence of environmental uncertainty on the effectiveness of PAS and OBMs

The KBV argues that in rapidly changing environments, access to and integration of specialist knowledge is even more important than in more stable environments for firm survival and growth (Grant 1996a). In stable environments, organizations make strategic plans and develop difficult-to-transfer routines in order to achieve competitive advantage. In uncertain environments, however, competitive advantage comes not from specialized routines but from adaptive capability (Volberda 1996). The main difference between a stable and a changing environment is that change cannot be predicted but only responded to ex post. Uncertainty requires organizations to be flexible, to enable them to respond to a wide variety of changes in the competitive environment in an appropriate and timely way (Volberda 1996).

According to Volberda (1996: p. 361), flexibility “is the degree to which an organization has a variety of managerial capabilities and the speed at which they can be activated.” In other words, in uncertain environments more than in stable environments, management needs an extensive, multidimensional collection of capabilities. Therefore, we expect that the impact of making use of external knowledge and capabilities will be stronger for firms operating in an uncertain environment than for those operating in a stable environment. Our third hypothesis is therefore:

-

Hypothesis 3 The impact of external knowledge on short-term start-up growth is stronger for firms operating in an uncertain environment.

3 Methodology

3.1 Sample and data collection

This study builds on three waves (2005, 2007, 2009) of a biennial population survey of new ventures located in Flanders (Belgium), called START (Policy Research Center for Entrepreneurship, Companies, and Innovation, 2001–2011). Each wave targeted all Flemish small new ventures between 1 and 3 years old with a minimum of one and a maximum of 49 employees that did not participate to an earlier START wave. The surveys were conducted in 2003, 2005, 2007, and 2009, and sought to obtain responses from the start-ups’ owners, as they typically possess the best knowledge of their firms’ history (Kor 2003). These survey data have previously been used for studies of the relationship between HRM and start-up innovation (De Winne and Sels 2010), the relationship between a business owner’s human and social capital, and the start-up’s absorptive capacity (Debrulle et al. 2013) and the identification of financially successful start-up profiles using data mining (Martens et al. 2011).

In this study, we concentrated on the last three waves (2005, 2007, 2009), since some survey questions crucial to our investigation, such as information on the composition of the board of directors and the prior start-up experience of the firm’s founding team, were not included in the 2003 questionnaire. This resulted in a sample of 1368 company observations,Footnote 1 of which 425 reported having a board of directors. For non-listed firms in Belgium, only public limited liability firmsFootnote 2 are legally obliged to have a board, and the choice to appoint external members is entirely voluntary. We eliminated 36 observations owing to incomplete survey data and dropped all firms for which no or incomplete financial data were collected from the Bureau Van Dijk’s Bel-first database. As a result, the final sample for this study consisted of 339 start-ups.Footnote 3

3.2 Definitions of variables

3.2.1 Dependent variable: firm growth

We measure short-term start-up growth as the relative employment growth between start-up and the end of the third fiscal year. In view of the context and theoretical foundation of this study, we opted to focus on employment growth rather than other frequently used measures of firm growth, such as sales growth or growth in total assets (Delmar et al. 2003). First, our study is theoretically grounded in the resource-/knowledge-based view of the firm, in which firms are seen as bundles of resources and knowledge. From this perspective, Delmar et al. (2003: p. 194) argue that “a growth analysis ought to focus on the accumulation of resources, such as employees.” Second, employment data are not generally considered to be confidential because they are usually widely disclosed. In contrast, obtaining extensive financial information on small firms is more difficult because they are not obliged to disclose financial data such as annual sales (Gilbert et al. 2006). Third, since a product or service has to be developed and produced before it can be brought to the market, employment growth is a precursor of increases in other growth indicators (Hanks et al. 1993). Fourth, employment growth is not sensitive to earnings management practices, as would be the case for a financial indicator such as profit growth.

To determine a suitable period over which to measure short-term growth, we had to make a trade-off between two factors. On the one hand, most start-up owner-managers are unlikely to have a multiple-year planning horizon (Johnson et al. 1999), meaning that in terms of growth measures, as short a period as possible should be considered. On the other hand, account must also be taken of the fact that it typically takes some time for externally acquired knowledge to be materialized in real economic performance (Cohen and Levinthal 1990). Therefore, in this study, we opted to use the first 3 years after foundation as the start-ups’ short-term growth period (Carr et al. 2010). Relative employment growth is typically calculated by dividing absolute growth by the firm’s initial level of employment. Since many start-ups have zero employees at founding, we calculate the percentage growth by applying the quotient rule for logarithms, using the employment level plus one rather than the actual employment level: \( \mathrm{pctEMPLgrowt}{\mathrm{h}}_{3\mathrm{y}}={e}^{\ln \left({\mathrm{EMPL}}_{\mathrm{y}3}+1\right)-\ln \left({\mathrm{EMPL}}_{\mathrm{y}1}+1\right)}-1 \). Employment data were collected from the firms’ annual accounts drawn from the Bel-first database.

3.2.2 Independent variables

Professional advisory services

As an indicator of PAS use, we use the total number of different PAS consulted by the firm. In the questionnaire, respondents were asked to indicate which advisory sources from a list of nine—accountant, lawyer, personnel and payroll administration, consultant, bank, general employers’ organization, sectoral employers’ organization, government, and other (Watson 2007)—they had ever made use of during the firm’s existence. A positive answer is coded “1,” and a negative answer “0.” The answers are summed to produce our PAS measure, which takes values between 0 and 9.

In previous literature, the use of PAS is measured in various ways, among others by a binary variable taking a value of “1” when PAS have been used and “0” otherwise (Robson and Bennett 2000), by the total number of advisory hours spent (Chrisman et al. 2005; Cumming and Fischer 2012), by the number of advisors that have worked with the firm (Cumming and Fischer 2012), and by client evaluations of the advisory services received (Chrisman and Katrishen 1994). Rather than considering the intensity of advisory use, our study focuses on the diversity of advisory services used by the start-up.

OBM presence

OBM presence is measured as the absolute number of outside members on the board of directors. OBMs are defined as directors who are neither members nor relatives of the firm’s founding team (Knockaert and Ucbasaran 2013).

3.2.3 Moderator variables

Initial knowledge stock of the firm (logEXP_IND and EXP_START)

The human capital of the founding team, as core organizational members, is perceived to be an important reservoir of initial knowledge and capabilities, and represents the firm’s level of absorptive capacity (Smith et al. 2005). Following Debrulle et al. (2013), we use prior relevant industry experience and previous start-up experience to measure the firm’s initial knowledge stock. We measure prior relevant industry experience as the total number of person years for which the entrepreneurial team has worked in the same industry (e.g., Siegel et al. 1993). For normalization purposes, we use the log-transformed version of this variable (logEXP_IND). We measure the founding team’s start-up experience (EXP_START) using a dummy variable taking a value of “1” if the founding team has start-up experience and “0” otherwise (Debrulle et al. 2013).

Environmental uncertainty (COMP and TO)

We measure environmental uncertainty by considering two factors that make the environment less predictable: environmental competitiveness and the perceived availability of technological opportunities. Environmental competitiveness (COMP) describes the extent to which the external environment is characterized by intense competition (Matusik and Hill 1998). We measure this using an index indicating from how many of four potential sources (new domestic firms, new foreign firms, established domestic firms, established foreign firms) the firm reported having experienced “fierce” or “very fierce” competition (Miller 1987). This index ranges between 0 and 4.

The availability of technological opportunities (TO) in a firm’s environment reflects the executive’s perceptions of the extent to which the environment offers opportunities for growth and technological change (Zahra 1996). To be successful in an environment with high technological opportunities, firms must quickly process large amounts of information on their competition, market, and customers (Galbraith 1973). To measure the availability of technological opportunities, we use three items introduced by Zahra (1993): (1) “Our industry offers many opportunities for technological innovation,” (2) “Demand for new technology in our industry is growing,” and (3) “New technology is needed for growth in this industry.” The Cronbach’s alpha is 0.842. To obtain our measure, we sum the items and divide by three. This measure ranges between 0 and 1, with an average of 0.466.

3.2.4 Control variables

Initial capital (log init. capital)

We control for initial capitalization, as firms with a higher initial financial capitalization tend to grow faster (Cooper et al. 1988). The amount of initial financial capital is measured as the natural log of paid-in (or contributed) capital reported in the first annual account after foundation.

Initial employment (log Init. EMPL)

We include the level of initial employment, measured as the natural logarithm of the employment level reported in the first annual accounts after foundation, as a methodological control variable (Davidsson et al. 2006).

Team size

The size of the founding team is important for growth because a larger size may “result in more extensive discussion of strategic options and more learning opportunities” (Lant et al. 1992: p. 591). Team size is measured as the number of people in the founding team.

Average founder age

The average age of the founding team is controlled for, as the owner/manager’s age tends to relate negatively to growth (Davidsson 1991).

Follower business

Following Debrulle et al. (2013), we control for the presence of follower businesses, using a dummy variable indicating whether the start-up’s business activities were already operational before the current organization was established.

Change in debt (change debt)

The entrepreneur’s ability to obtain capital from external sources such as banks and other capital providers is particularly important for the growing firm (Lee et al. 2001). As a proxy for the change in ability to obtain external financing during the period of observation (i.e., the first 5 years after foundation), we include change debt, measuring the relative difference in total debt reported in the annual accounts of the first and fifth years after the firm’s foundation.

Foundation year

Since imprinting at the time of founding and the general conditions of the country may impact on new firms’ success/failure (Stinchcombe 1965), we control for foundation year using year dummies.

Industry

The following eight industries are included in the analysis to control for industry characteristics (e.g. McDougall et al. 1994): agriculture, manufacturing, construction, retail, transportation, banking and insurance, personal services, and professional services.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics and correlations for the variables used in our empirical tests. We calculated variance inflation factors (VIFs) and found no indication of potential multicollinearity problems, the highest VIF being 1.56 (Kleinbaum et al. 1998).

4.2 Regression results

To rule out possible endogeneity in our variables of interest owing to self-selection bias, we started by performing a Hausman test, which pointed to hierarchical ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis as the most appropriate estimation method to test our hypotheses. We adjusted standard errors for heteroscedasticity. Table 2 presents the results of the Hausman test, and Tables 3 and 4 present the results of our main analyses.

Since firms must choose whether or not to appoint outside members to their boards of directors and/or to make use of PAS, there is a risk of self-selection bias in our model. This may give rise to endogeneity in the explanatory variables (Wooldridge 2015). Therefore, we estimate our model using instrumental variable (IV) estimation and OLS estimation. Previous literature (Voordeckers et al. 2007) suggests that majority-owned firms are less likely to have OBMs. Therefore, we introduce Family_Majority, a dummy variable taking a value of 1 when 50% or more of shares is owned by one person or one family and zero otherwise, as an instrumental variable for OBM. Family_Majority is negatively correlated with OBM (r = − 0.3367, p < 0.000) and is not significantly correlated with employment growth, which indicates instrument relevance and exogeneity. Using this instrumental variable in the IV estimation, the Hausman test finds no significant differences in the estimated coefficients from OLS and IV (see Table 2). As an instrumental variable for PAS, we use an index indicating the extent of the firm’s use of its social capital. The previous literature shows that when firms make active use of their social networks to obtain free advice, they will also be more open and willing to make use of paid advice (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998). Social_Capital is positively correlated with PAS (r = 0.3116, p < 0.000) and is not significantly correlated with employment growth, which indicates instrument relevance and exogeneity. Using this instrumental variable in the IV estimation, the Hausman test finds no significant differences in the estimated coefficients from OLS and IV (see Table 2). Based on these results, we use OLS as the estimation method for our analyses in Table 3 (focusing on PAS) and Table 4 (focusing on OBM).

Model 1 includes the control and moderator variables. We add our two independent variables (PAS and OBM) into model 2 to examine hypothesis 1. Model 2 indicates a positive coefficient for PAS (0.0811, p < 0.01), whereas the coefficient for OBM is insignificant (− 0.00168, p > 0.10). This provides partial support for H1a, as only PAS is positively associated with short-term start-up growth. Hypothesis 1b posits that the impact of the use of PAS is more important than the impact of OBM on short-term start-up employment growth. The results suggest that the former appears to be more important than the latter in realizing short-term employment growth, supporting Hypothesis 1b.

Models 3 and 4 report the test results for Hypothesis 2, which predicts that the impact on short-term start-up growth of using external knowledge sources will be stronger when the firm’s initial knowledge stock is higher. In model 3, the natural logarithm of the founding team’s total prior relevant industry experience (logEXP_IND) is used as a proxy for initial knowledge stock. In model 4, the initial knowledge stock is proxied by EXP_START, a dummy variable indicating whether or not start-up experience is present among the founders. The interaction term of PAS with prior relevant industry experience is significant (− 0.0549, p < 0.05), but in the opposite direction from that expected, whereas the interaction term with start-up experience is insignificant (0.0053, p > 0.10). Taking these results together, Hypothesis 2 is not supported for PAS, as having prior industry experience moderates the impact of PAS on the startup’s short-term growth, such that PAS has a smaller effect on performance than in firms without founders’ industry experience. For OBMs (Table 4), neither the interaction term with prior relevant industry experience (− 0.0935, p > 0.10) nor the interaction term with prior start-up experience appear to be significant (− 0.0911, p > 0.10) at the 5% level. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is not supported: having prior industry or start-up experience does not accentuate the impact of having OBMs on start-ups’ short-term performance.

Models 5 and 6 report the test results for Hypothesis 3, which states that the effect of external knowledge sources on start-up growth will be stronger when environmental uncertainty is higher. In model 5, environmental competitiveness (COMP) is used as a proxy for the uncertainty of the external environment, and in model 6, environmental uncertainty is proxied by the availability of technological opportunities (TO). In Table 3, the interaction of PAS with COMP is insignificant (− 0.0318, p > 0.10), whereas the interaction with TO is positively significant (0.3638, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 3 is thus partially supported, as using PAS as an external knowledge source is more strongly associated with employee growth in environments offering technological opportunities. For OBMs (Table 4), neither the interaction term with COMP (0.00127, p > 0.10) nor the interaction term with TO (0.1085, p > 0.10) is significant. Taking these results together, for OBMs, both interaction variables proxying for environmental uncertainty are insignificant, so Hypothesis 3 is not supported.

To further interpret the significant interactions, we perform a simple slope analysis (Aiken and West 1991). Graphs depicting the results of model 3 (Hypothesis 2 with PAS as external knowledge source) and model 6 (Hypothesis 3 with PAS as external knowledge source) are presented in Figs. 1 and 2, in which a low level of the variable is one standard deviation below the average, while a high level of the variable is one standard deviation above the average.

In Fig. 1, the slope of the low EXP_IND line is much steeper than the slope of the high EXP_IND line. This means that the impact of PAS is much higher for firms with low prior relevant industry experience than for firms with higher prior relevant industry experience. We can conclude that the level of prior relevant industry experience is a crucial factor influencing the impact of PAS on start-ups’ short-term employment growth. However, a different mechanism from the one hypothesized in Hypothesis 2 appears to be working here. In Fig. 2, the slope of the high TO line is much steeper than the slope of the low TO line. The difference in slope shows that the impact of PAS on start-ups’ short-term growth is much higher for firms operating in an environment with abundant technological opportunities than for firms operating in an environment with fewer technological opportunities. Our results suggest that in addition to the internal context (industry experience rather than start-up experience), the external context (availability of technological opportunities rather than competitive pressure) is also an important factor influencing the effectiveness of PAS.

4.3 Supplementary and sensitivity analysis Footnote 4

To test the robustness of our results, we ran a number of sensitivity analyses relating to the measurement of short-term performance. We also checked whether controlling for selection bias altered the results, and tested whether changes to the model design altered the results found.

We tested the sensitivity of the results using three alternative proxies for short-term performance. First, we repeated the analysis using relative employment growth between foundation and year 5 to allow for a longer time lag to enable the use of external knowledge sources to really come into effect. Our results remained similar to those from the basic model. Second, we used absolute rather than relative employment growth as the dependent variable, and the results remained similar. Third, we re-ran the regression using the deviation of the firm’s relative employment growth between foundation and year 3 from the average growth of sample firms in the same industry as the dependent variable. All results remained consistent.

To test the sensitivity of the results relating to the operationalization of PAS, we further examined the influence of PAS on start-up growth by assessing whether its effect depends on whether or not the advisory services included in the PAS measure are voluntary or compulsory. We split PAS based on the legitimacy power of the service, in terms of whether or not they are legally obligatory. For instance, although neither hiring an accountant nor using a personnel and payroll administration office (PPA) are strictly compulsory, all firms must meet certain financial and legal obligations, such as preparing and submitting correct financial accounts in accordance with the law. In our sample, 94% of firms reported using an accountant and 75% had made use of the services of a PPA. Building on this, we re-ran the analyses, using PAS without an accountant, PAS without a PPA, and PAS with neither accountant nor PPA. The results show that PAS remained statistically significant when one or both virtually compulsory advisory services were omitted, reinforcing our evidence supporting Hypothesis 1.

Third, in order to check whether our results were driven by a specific choice of conceptualization or operationalization of the concept of “OBM,” we tested six alternative board outsider conceptualization/operationalization combinations. We considered two different conceptualizations of outside directors: “outsiders in a lenient sense” and “outsiders in a strict sense.” The latter is stricter, since it excludes all directors with shares in the company. Furthermore, we operationalized the presence of outside directors in three ways: (1) as a simple dummy variable, indicating the presence or absence of outsiders on the board; (2) by the absolute number of outsiders; and (3) by the proportion of outsiders relative to total board size. We re-ran the regressions for each of the six possible outsider conceptualization/operationalization combinations, which consistently produced the same results as those previously reported. We also examined whether the insignificance of OBMs was a consequence of Belgian company legislation stating that public limited companies must have a minimum of three board members (or two when there are only two shareholders). OBMs might have been added to these firms’ boards of directors simply to comply with the legal minimum number of board members. Therefore, owing to the presence of these so-called “paper OBMs” who do not actively contribute to firms’ strategy and operations, the real effect of OBMs’ presence might be negatively biased. Consequently, we re-ran the regressions, excluding all firms with a board of directors consisting of three or fewer board members and containing at least one OBM. Again, the results remained unchanged, implying that the insignificant impact of OBMs is not attributable to the presence of “paper OBMs.”

To check for possible self-selection issues regarding the choice of whether or not to make use of PAS or to engage OBMs, we ran two Heckman selection models. In the PAS model, we considered firms making use only of virtually compulsory advisors, such as accountants and PPA (N = 52), versus firms also voluntarily making use of other advisors (N = 287). In the OBM model, the selection equation considers firms with outside board members (N = 65) versus firms without outside board members (N = 274). The inverse Mills ratio was not significant in either of the two models, suggesting that there is no risk of biased estimators due to self-selection issues. Therefore, we continued to use ordinary least squares regression.

Finally, to allow for possible diminishing returns of PAS and OBMs, we added both squared terms to the regression model. Neither was significant, suggesting no evidence of diminishing returns from using PAS or OBMs.

5 Discussion

In this study, we consider two sources of external knowledge: PAS and OBMs. Our results underscore the following: (i) the role of PAS as an important driver of start-up growth and the effect of the founding team’s prior relevant industry experience and the availability of technological opportunities in the firm’s external environment in inhibiting and fostering the relationship between PAS and start-up growth; and (ii) OBMs’ presence as a non-significant contributor to start-up growth. Table 5 provides a summary of the results for each hypothesis.

5.1 Implications for theory

This study advances both the governance and entrepreneurship literatures by connecting past research on the performance effects of external advisory use (Robson and Bennett 2000) and board composition (Hillman and Dalziel 2003). We find that the use of PAS is positively associated with start-up growth, whereas the presence of outside members on the board of directors, even after contextualization, is not associated with our dependent variable. This finding supports the argument that professional advisors provide crucial services to start-ups (Clayton et al. 2018) One possible explanation for the absence of a relationship between OBM presence and start-up growth is that the relationship may be more complex and indirect (Forbes and Milliken 1999). More detailed information on actual board processes and board behavior would presumably allow the construction of a more solid link between inputs (i.e., board composition and demographics) and outputs (firm performance and growth). Unfortunately, data limitations prevent us from exploring board processes in start-ups in greater detail. Future studies might employ a more qualitative approach to provide new insights into the mechanisms through which external board members contribute to firm growth.

Another potential explanation may relate to the type of external board members that firms hire.Footnote 5 Reciprocal interlocking may be present for some external board members, with the directors of two firms sitting on each other’s boards (Hallock 1997). Such interlocking directorates are a non-trivial phenomenon and occur regularly across industries (Fich and White 2005). While interlocks are often considered to be beneficial for firms, reciprocally interlocking directorates may promote cronyism, thereby reducing efficiency and limiting the board’s influence on firm performance (Yeo et al. 2003). As data limitations prevent us from investigating this in greater detail, we leave it to future research to explore the effect of reciprocal interlocks on start-ups’ performance.

A third possible explanation for the insignificance of OBMs is the time frame used in this study. Our results show that in the short term, the presence of OBMs has no significant growth impact on start-ups. This result does not necessarily imply that OBMs are less useful for start-ups, but the effects of their actions on firm growth may only become visible after a longer period. However, owing to data limitations we are unable to dig deeper into this phenomenon, and therefore encourage future research on the longer-term growth impact of OBMs in the start-up context.

Our results also show that the effectiveness of PAS is negatively influenced by the level of initial knowledge stock (measured by the founding team’s prior relevant industry experience). The potential negative impact of higher absorptive capacity may arise from the fact that novel and external knowledge will always be funneled into existing mental models and ways of doing things (Winter 2003). This implies that individuals who are not hampered by any prior knowledge may be able to apply the new knowledge more directly, whereas more knowledgeable individuals may tend to use it to confirm their existing modi operandi, rather than changing them. Another explanation for the negative impact of initial knowledge stock on the effectiveness of PAS is drawn from the decision-making literature, which argues that when receiving advice, the decision-maker is often exposed to a potential conflict between his own initial opinion and the advice. Yaniv and Kleinberger (2000) introduce the concept of “egocentric discounting,” which implies that when faced with a discrepancy between their own opinion and the advice, decision-makers tend to discount even high-quality advisors’ opinions in the combination process. Individuals with a higher knowledge stock are able to retrieve more evidence from their memories than less knowledgeable individuals to form their personal opinions, and may therefore weigh their own opinions more highly (Yaniv 2004). Thus, compared with serial entrepreneurs, novice entrepreneurs are more likely to believe that external advice is crucial for achieving firm growth (Westhead et al. 2005), making them more open to external advice. Our findings seem to be consistent with egocentric discounting behavior.

Our results also show that it is not uncertainty stemming from environmental competitiveness but rather uncertainty stemming from the availability of technological opportunities in the sector that have an impact on the effectiveness of PAS on start-up growth. In environments rich in technological opportunities, competitive advantages are typically short-lived (Covin and Slevin 1989; Zahra 1996), whereas in less turbulent, more stable environments, competitive advantages may be more sustainable. Increased levels of anxiety resulting from typically short-lived competitive advantages make decision-makers more likely not only to seek advice but also to use this advice, even if it is of poor quality (Gino et al. 2012). In contrast, a high level of competitive pressure does not necessarily trigger decision-makers’ anxiety (or reduce their self-confidence). When a firm’s competitive advantage is sustainable, greater competitive pressure does not increase the need for quick processing of external information. In short, our findings show that it is not the level of competitive pressure as such but the nature (and more specifically the sustainability) of the competitive advantage that makes PAS more effective.

5.2 Implications for practitioners and policymakers

The results show that in the specific context of start-ups, there is no immediate need to spend valuable resources on composing an extensive board of directors with outsider representation. Such firms are better off simply making use of specialist advisory services on an ad hoc basis. However, it should be noted that the effectiveness of this advisory use is highly dependent on the founding team’s prior relevant industry experience and the availability of technological opportunities in the start-up’s environment. As explained in the “Implications for theory” section, we believe that efficiency gains and losses stem largely from the discounting behavior of those receiving advice. Making managers aware of the potentially negative effects of such behavior may enable them to make more conscious decisions on whether to follow their own or their advisors’ opinions.

This information is also of value to policymakers responsible for creating a stimulating and supportive environment for start-ups. In several countries, start-ups are offered subsidized private external consultancy (Cumming and Fischer 2012). This study shows that making use of external advisory services has a significant impact on start-ups’ employment growth, confirming the value of subsidized sources of external knowledge. For resource-constrained policymakers, the outcomes of investigating boundary conditions might be a source of inspiration to select advisory beneficiaries more specifically.

5.3 Limitations and future research directions

This study has limitations that open avenues for future research. First, it employs data on new ventures in one region of Belgium, Flanders, which reduces the unobserved heterogeneity. Nevertheless, studying firms exclusively in one region may raise questions about the generalizability to firms in other geographical or cultural contexts. There is no reason to believe that the theoretical relationship between the key variables in the model should not hold for start-ups operating in different contexts, but studies of new ventures in different regions would contribute to the generalizability of our findings.

Somewhat unexpectedly, some control variables in our analysis show a small (e.g., human capital variables) or zero effect (e.g., capital) on employment growth.Footnote 6 However, other studies of start-ups’ employment growth provide similar findings (e.g., Westhead and Birley 1995; Ostgaard and Birley 1996; Hmieleski and Baron 2009). In explaining the finding that human capital is not associated with employment growth, Westhead and Birley (1995: p. 26) point out that it “is the strategic decisions which owner-managers make… which influence employment growth.” Since the abovementioned variables are used as control variables in our study, a detailed investigation of these findings is beyond the scope of our study. However, future studies might focus on these variables to explore the conditions under which they influence employment growth in start-ups.

Finally, while we examine the influence of external knowledge sources on firm performance, future studies might consider other dependent variables. Studies of how external knowledge sources impact on the professionalization of new ventures would be particularly insightful. Such studies might adopt a life-cycle perspective to shed new light on the importance of different types of external knowledge sources in different phases of the company’s life cycle.

Notes

The start-ups that satisfied START inclusion conditions consisted of 3172 in 2005, 3251 in 2007, and 3183 in 2009. Owing to missing company data, 275, 301, and 259 of these start-ups, respectively, could not be used. For the remaining start-ups, a total of 1368 company questionnaires (412, 491, and 465, respectively) were obtained, corresponding with response rates of 14.2%, 16.7%, and 15.9%, respectively. These are comparable with other surveys of small business owners (Baron and Tang 2011; Menon et al. 1999; Sousa et al. 2008). To check for non-response bias, responding and non-responding firms were compared by organization size (number of employees, total assets, and equity), age, and industry. The results of chi-square difference and t tests revealed no significant differences.

In a public limited liability company, there must always be at least three directors. In a private limited liability company and all other company types, there is no formal obligation to have a board of directors. The “public” versus “private” distinction in this context refers to whether the firm’s shares are freely transferable to other parties (“public” LLC) or subject to certain conditions (“private” LLC). Thus, it does not refer to whether or not the firm is publicly listed on the stock market.

The start-ups included in our analyses were weighed against those not included (e.g., because of missing values for one or more of the variables). The results of chi-square difference and t tests revealed no significant differences.

Statistical tables showing these results are available on request from the corresponding author.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for bringing this to our attention.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Baron, R. A., & Tang, J. (2011). The role of entrepreneurs in firm-level innovation: joint effects of positive affect, creativity, and environmental dynamism. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.06.002.

Bolton, M. K. (1999). The role of coaching in student teams: a “just-in-time” approach to learning. Journal of Management Education, 23(2), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/105256299902300302.

Boone, A. L., Casares Field, L., Karpoff, J. M., & Raheja, C. G. (2007). The determinants of corporate board size and composition: an empirical analysis. Journal of Financial Economics, 85(1), 66–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.05.004.

Brandenburg, D. C., & Ellinger, A. D. (2003). The future: just-in-time learning expectations and potential implications for human resource development. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 5(3), 308–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422303254629.

Brunninge, O., Nordqvist, M., & Wiklund, J. (2007). Corporate governance and strategic change in SMEs: the effects of ownership, board composition and top management teams. Small Business Economics, 29(3), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-006-9021-2.

Carr, J. C., Haggard, K. S., Hmieleski, K. M., & Zahra, S. A. (2010). A study of the moderating effects of firm age at internationalization on firm survival and short-term growth. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 4(2), 183–1852. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.90.

Casson, M. (1996). The comparative organisation of large and small firms: an information cost approach. Small Business Economics, 8(5), 329–345.

Chrisman, J. J., & Katrishen, F. (1994). The economic impact of small business development center counseling activities in the United States: 1990–1991. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(4), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(94)90008-6.

Chrisman, J. J., & McMullan, W. E. (2000). A preliminary assessment of outsider assistance as a knowledge resource: the longer-term impact of new venture counseling. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 24(3), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225870002400303.

Chrisman, J. J., & McMullan, W. E. (2004). Outsider assistance as a knowledge resource for new venture survival. Journal of Small Business Management, 42(3), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2004.00109.x.

Chrisman, J. J., McMullan, E., & Hall, J. (2005). The influence of guided preparation on the long-term performance of new ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(6), 769–791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.10.001.

Clarysse, B., Knockaert, M., & Lockett, A. (2007). Outside board members in high tech start-ups. Small Business Economics, 29, 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-006-9033-y.

Clayton, P., Feldman, M., & Lowe, N. (2018). Behind the scenes: Intermediaryorganizations that facilitate science commercialization throughentrepreneurship. Academy of Management Perspectives, 32(1), 104–124. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2016.0133.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393553.

Cooper, A. C., Woo, C. Y., & Dunkelberg, W. C. (1988). Entrepreneurs’ perceived chances for success. Journal of Business Venturing, 3(2), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(88)90020-1.

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1989). Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250100107.

Cowling, M., & Mitchell, P. (2003). Is the small firms loan guarantee scheme hazardous for banks or helpful to small business? Small Business Economics, 21(1), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024408932156.

Cumming, D. J., & Fischer, E. (2012). Publicly funded business advisory services and entrepreneurial outcomes. Research Policy, 41(2), 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.09.004.

Daily, C. M., McDougall, P. P., Covin, J. G., & Dalton, D. R. (2002). Governance and strategic leadership in entrepreneurial firms. Journal of Management, 28(3), 387–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630202800307.

Davidsson, P. (1991). Continued entrepreneurship: ability, need and opportunity as determinants of small firm growth. Journal of Business Venturing, 6(6), 405–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(91)90028-C.

Davidsson, P., Delmar, F., & Wiklund, J. (2006). Entrepreneurship and the growth of firms. Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Davila, A., Foster, G., & Jia, N. (2010). Building sustainable high-growth startup companies: management systems as an accelerator. California Management Review, 52(3), 79–105. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2010.52.3.79.

De Winne, S., & Sels, L. (2010). Interrelationships between human capital, HRM and innovation in Belgian start-ups aiming at an innovation strategy. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(11), 1863–1883. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2010.505088.

Debrulle, J., Maes, J., & Sels, L. (2013). Start-up absorptive capacity: does the owner’s human and social capital matter? International Small Business Journal, 32(7), 777–801. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242612475103.

Delmar, F., Davidsson, P., & Gartner, W. B. (2003). Arriving at the high-growth firm. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(2), 189–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00080-0.

Dyer, L., & Ross, C. A. (2007). Advising the small business client. International Small Business Journal, 25(2), 130–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242607074517.

Fich, E. M., & White, L. J. (2005). Why do CEOs reciprocally sit on each other’s boards? Journal of Corporate Finance, 11(1–2), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2003.06.002.

Fiegener, M. (2005). Determinants of board participation in the strategic decisions of small corporations. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 29(5), 627–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00101.x.

Forbes, D. P., & Milliken, F. J. (1999). Cognition and corporate governance: understanding boards of directors as strategic decision-making groups. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 489–505. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.2202133.

Galbraith, J. R. (1973). Designing complex organizations. organization development. Boston: Addison-Wesley.

Garg, S. (2013). Venture boards: distinctive monitoring and implications for firm performance. S Garg. Academy of Management Review, 38(1), 90–108. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2010.0193.

Garg, S., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2017). Unpacking the CEO–board relationship: how strategy making happens in entrepreneurial firms. Academy of Management Journal, 60(5), 1828–1858. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0599.

Gilbert, B. A., McDougall, P. P., & Audretsch, D. B. (2006). New venture growth: a review and extension. Journal of Management, 32(6), 926–950. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306293860.

Gino, F., Brooks, A. W., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2012). Anxiety, advice, and the ability to discern: feeling anxious motivates individuals to seek and use advice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(3), 497–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026413.

Grant, R. M. (1996a). Prospering in dynamically-competitive environments: organizational capability as knowledge integration. Organization Science, 7(4), 375–387. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.7.4.375.

Grant, R. M. (1996b). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250171110.

Hallock, K. F. (1997). Reciprocally interlocking boards of directors and executive compensation. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 32(3), 331–343. https://doi.org/10.2307/2331203.

Hanks, S. H., Watson, C. J., Jansen, E., & Chandler, G. N. (1993). Tightening the life-cycle construct: a taxonomic study of growth stage configurations in organizations. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 18(2), 5–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879401800201.

Hillman, A. (2015). Board diversity: beginning to unpeel the onion. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 23(2), 104–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12090.

Hillman, A. J., & Dalziel, T. (2003). Boards of directors and firm performance: integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2003.10196729.

Hmieleski, K. M., & Baron, R. A. (2009). Entrepreneurs’ optimism and new venture performance: a social cognitive perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 52(3), 473–488. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.41330755.

Johnson, P., Conway, C., & Kattuman, P. (1999). Small business growth in the short run. Small Business Economics, 12(2), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008006516084.

Johnson, S., Webber, D. J., & Thomas, W. (2007). Which SMEs use external business advice? A multivariate subregional study. Environment and Planning A, 39(8), 1981–1997. https://doi.org/10.1068/a38327.

Kleinbaum, D., Kupper, L., & Muller, K. (1998). Applied regression analysis and other multivariable methods (3rd ed.). Pacific Grove: Duxbury Press.

Knockaert, M., & Ucbasaran, D. (2013). The service role of outside boards in high tech start-ups: a resource dependency perspective. British Journal of Management, 24(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2011.00787.x.

Kor, Y. Y. (2003). Experience-based top management team competence and sustained growth. Organization Science, 14(6), 707–719. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.14.6.707.24867.

Lant, T. K., Milliken, F. J., & Batra, B. (1992). The role of managerial learning and interpretation in strategic persistence and reorientation: an empirical exploration. Strategic Management Journal, 13(8), 585–608. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250130803.

Lazear, E. P. (2004). Balanced skills and entrepreneurship. American Economic Review, 94(2), 208–211. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828041301425.

Lee, C., Lee, K., & Pennings, J. M. (2001). Internal capabilities, external networks, and performance: a study on technology-based ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7), 615–640. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.181.

Macpherson, A., & Holt, R. (2007). Knowledge, learning and small firm growth: a systematic review of the evidence. Research Policy, 36(2), 172–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2006.10.001.

Maister, D., Green, C., & Galford, R. (2000). The trusted advisor. New York: The Free Press.

Martens, D., Vanhoutte, C., De Winne, S., Baesens, B., Sels, L., & Mues, C. (2011). Identifying financially successful start-up profiles with data mining. Expert Systems with Applications, 38(5), 5794–5800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2010.10.052.

Matusik, S. F., & Hill, C. W. L. (1998). The utilization of contingent knowledge creation, and competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 680–697. https://doi.org/10.2307/259057.

McDougall, P. P., Covin, J. G., Robinson, R. B., & Herron, L. (1994). The effects of industry growth and strategic breadth on new venture performance and strategy content. Strategic Management Journal, 15(7), 537–554. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250150704.

Menon, A., Bharadwaj, S. G. S., Adidam, P. T., & Edison, S. W. (1999). Antecedents and consequences of marketing strategy making: a model and a test. Journal of Marketing, 63(2), 18–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299906300202.

Miller, D. (1987). Strategy making and structure: analysis and implications for performance. Academy of Management Journal, 30(1), 7–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/255893.

Miner, A. S., & Mezias, S. J. (1996). Ugly duckling no more: pasts and futures of organizational learning research. Organization Science, 7(1), 88–99. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.7.1.88.

Mole, K. (2002). Business advisers’ impact on SMEs: an agency theory approach. International Small Business Journal, 20(2), 139–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242602202002.

Mole, K. F., Hart, M., Roper, S., & Saal, D. S. (2009). Assessing the effectiveness of business support services in England: evidence from a theory-based evaluation. International Small Business Journal, 27(5), 557–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242609338755.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital and the organizational advantage. The Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.533225.

Ostgaard, T. A., & Birley, S. (1996). New venture growth and personal networks. Journal of Business Research, 36(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(95)00161-1.

Ratinho, T., Amezcua, A., Honig, B., & Zeng, Z. (2020). Supporting entrepreneurs: a systematic review of literature and an agenda for research. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 154, 119956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119956.

Robson, P., & Bennett, R. J. (2000). SME growth: the relationship with business advice and external collaboration. Small Business Economics, 15(3), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008129012953.

Rubin, T. H., Aas, T. H., & Stead, A. (2015). Knowledge flow in technological business incubators: evidence from Australia and Israel. Technovation, 41-42, 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2015.03.002.

Sapienza, H. J., Autio, E., George, G., & Zahra, S. A. (2006). A capabilities perspective on the effects of early internationalization on firm survival and growth. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 914–933. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.22527465.

Schulze, W. S., Lubatkin, M. H., & Dino, R. N. (2003). Exploring the agency consequences of ownership dispersion among the directors of private family firms. Academy of Management Journal, 46(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.5465/30040613.

Siegel, R., Siegel, E., & Macmillan, I. C. (1993). Characteristics distinguishing high growth ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(2), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(93)90018-Z.

Smith, K. G., Collins, C. J., & Clark, K. D. (2005). Existing knowledge, knowledge creation capability, and the rate of new product introduction in high-technology firms. Academy of Management Journal, 48(2), 346–357. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.16928421.

Sousa, C. M. P., Martínez-López, F. J., & Coelho, F. (2008). The determinants of export performance: a review of the research in the literature between 1998 and 2005. International Journal of Management Reviews, 10(4), 343–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00232.x.

Stinchcombe, A. L. (1965). Social structure and organization. In J. G. March (Ed.), Handbook of organizations (pp. 153–193). Chicago: Rand McNally.

Uhlaner, L., Wright, M., & Huse, M. (2007). Private firms and corporate governance: an integrated economic and management perspective. Small Business Economics, 29(3), 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-006-9032-z.

Van Den Heuvel, J., Van Gils, A., & Voordeckers, W. (2006). Board roles in small and medium-sized family businesses: performance and importance. Corporate Governance, 14(5), 467–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2006.00519.x.

Van Doorn, S., Heyden, M. L. M., & Volberda, H. W. (2017). Enhancing entrepreneurial orientation in dynamic environments: the interplay between top management team advice-seeking and absorptive capacity. Long Range Planning, 50(2), 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2016.06.003.

Vivas, C., & Barge-Gil, A. (2015). Impact on firms of the use of knowledge external sources: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Economic Surveys, 29(5), 943–964. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12089.

Volberda, H. W. (1996). Toward the flexible form: how to remain vital in hypercompetitive environments. Organization Science, 7(4), 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.7.4.359.

Voordeckers, W., Van Gils, A., & Van Den Heuvel, J. (2007). Board composition in small and medium sized family firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 45(1), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2007.00204.x.

Watson, J. (2007). Modeling the relationship between networking and firm performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(6), 852–874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.08.001.

Westhead, P., & Birley, S. (1995). Employment growth in new independent owner-managed firms in Great Britain. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 13(3), 11–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242695133001.

Westhead, P., Ucbasaran, D., Wright, M., & Binks, M. (2005). Novice, serial and portfolio entrepreneur behaviour and contributions. Small Business Economics, 25(2), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-003-6461-9.

Winter, S. G. (2003). Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 991–995. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.318.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2015). Introductory econometrics: a modern approach. Nashville: Nelson Education.

Yaniv, I. (2004). Receiving other people’s advice: influence and benefit. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 93(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2003.08.002.

Yaniv, I., & Kleinberger, E. (2000). Advice taking in decision making: egocentric discounting and reputation formation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 83(2), 260–281. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.2000.2909.

Yeo, H.-J., Pochet, C., & Alcouffe, A. (2003). CEO reciprocal interlocks in French corporations. Journal of Management and Governance, 7, 87–108. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022442602193.

Zahra, S. A. (1993). Environment, corporate entrepreneurship, and financial performance: a taxonomic approach. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(4), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(93)90003-N.

Zahra, S. A. (1996). Goverance, ownership, and corporate entrepreneurship: the moderating impact of industry technological opportunities. The Academy of Management Journal, 39(6), 1713–1735. https://doi.org/10.5465/257076.

Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). Absorptive capacity: a review, and extension. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 185–203. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2002.6587995.

Zahra, S. A., & Pearce, J. A. (1989). Boards of directors and corporate financial performance: a review and integrative model. Journal of Management, 15(2), 291–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638901500208.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weemaes, S., Bruneel, J., Gaeremynck, A. et al. Initial external knowledge sources and start-up growth. Small Bus Econ 58, 523–540 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00428-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00428-7