Abstract

In this paper, we first develop an original theory in which, based on their individual skills and the quality of their business, entrepreneurs can keep their original business (and thus remain novice entrepreneurs), start and keep a new business in the same or another sector along their current business (therefore becoming portfolio entrepreneurs), transfer or shut their original business down to either start a new one (turning themselves into serial entrepreneurs), or enter the labor market as wage workers. We then use the insights from our theory to develop three main hypotheses that are finally tested for a 10-year panel dataset (2001 to 2010) of more than 4000 Vietnamese manufacturing firms. We estimate an occupational choice model and a survival model and find that (i) a greater endowment of human capital is associated with a higher likelihood of a business owner to become a serial or a portfolio entrepreneur; (ii) a higher quality of the new business is associated to a higher likelihood that it is run by any type of habitual entrepreneur. Particularly, high entrepreneurial skills together with a high-quality business positively influence the likelihood of an individual to be serial or portfolio entrepreneur; (iii) ceteris paribus, firms run by serial or portfolio entrepreneurs tend to stay in business longer, although high-quality ones run by novice entrepreneurs endowed with high entrepreneurial skills are those with the lowest probability to leave the market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

We present, and test for the case of Vietnam, an original theory of what may lead first-time (novice) entrepreneurs to continue to run the original business that they have launched, or to become habitual entrepreneurs who run multiple businesses, either sequentially (serial entrepreneurs) or in parallel (portfolio entrepreneurs).Footnote 1

It is our opinion that the study of portfolio and serial entrepreneurship is relatively underdeveloped in the extant literature (Carter and Ram 2003), and therefore, scope exists for strengthening both the theoretical framework and the empirical evidence upon which it relies and by which it is supported.Footnote 2

Theoretical research on habitual entrepreneurship and occupational choices amounts to very few papers (Holmes and Schmitz Jr 1990; Plehn-Dujowich 2010; Parker 2014). Of these papers, Holmes and Schmitz Jr (1990) and Plehn-Dujowich (2010) focus only on novice and serial entrepreneurs, neglecting portfolio entrepreneurship. Plehn-Dujowich (2010) pays particular attention to the individual’s occupational choice, rather than to the equilibrium dynamics of firm transfers. However, the linear structure of the production technology in his model makes it impossible to study portfolio entrepreneurship: in the equilibrium, all available capital is invested in a unique enterprise (the one with the highest expected profitability) and no scenario in which an entrepreneur runs multiple businesses simultaneously can arise endogenously.

Parker (2014) models portfolio entrepreneurship explicitly. His main focus is on the role that recognition and exploitation abilities play in the occupational choice of individuals. In his model, owning a portfolio of firms is valuable for risk-averse entrepreneurs, as it helps them diversify their entrepreneurial risk and mitigates income variance. Thus, risk aversion and diversification are the only motivations for portfolio entrepreneurship, and issues related to firm quality and production technology are neglected.

All these papers are therefore somehow limited in scope and do not allow us to formulate testable predictions able to exploit the unique characteristics and richness of our dataset.

Albeit more abundant, empirical research suffers from the lack of suitable data and from the inadequate analysis of some important features of the determinants of the entrepreneurial choice (Parker 2012, 2013; Sarasvathy et al. 2013; Rocha et al. 2015; Lafontaine and Shaw 2016). Most studies, in fact, compare the choice and economic outcomes of remaining a novice with that of becoming a habitual entrepreneur, neglecting the choice between portfolio and serial entrepreneurship.Footnote 3

When studying the occupational choices between portfolio and serial entrepreneurship, not only it is important to understand what transforms a novice entrepreneur into a habitual entrepreneur but also what makes her/him choose portfolio entrepreneurship over serial and vice versa. Theory-driven findings might prove useful for both individuals facing the decision of choosing among novice, portfolio, serial entrepreneurship, and policy makers interested in designing and implementing entrepreneurship policies. Placing the occupational choice of the entrepreneur within the entrepreneurial opportunity research, the phenomenon of multibusiness entrepreneurship has been a special interest for policy makers and practitioners, not only because habitual entrepreneurs possess unique characteristics, but also because, given their experience and expertise, they can identify more entrepreneurial opportunities and hold more promise for success and growth as future business owners (Westhead et al. 2005, 2009; Lafontaine and Shaw 2016; Wang et al. 2017).

To add to the body of existent literature, we first present an original theoretical model that sheds new light on the phenomena of interest. It shows that, based on the quality of their current business, on the expected quality of their prospective new business, on their entrepreneurial skills, and the size of their initial investment, first-time entrepreneurs can alternatively become habitual entrepreneurs (either portfolio or serial) or remain novice.

The main contribution of this model for advancement of our understanding of entrepreneurship is in considering portfolio and serial entrepreneurship as two separate occupational choices, rather than putting them together as habitual entrepreneurship. It also looks at the dynamics of the entrepreneur’s investment decisions, while other studies normally give a one-shot or static comparative analysis of the various occupational choices.Footnote 4 Besides, it is the first model explaining the occupational choice between novice, serial, and portfolio entrepreneurship in terms of productive ability, capital investment, and the relative quality of both the current and the new business. Although entrepreneurs are in general very heterogeneous, comprising both “stars” (high human capital) and “misfits” (low human capital) (Åstebro et al. 2011; see also Santarelli and Vivarelli 2007), we are able to prove that, while serial entrepreneurs are highly skilled individuals facing a new opportunity with a very good expected quality, portfolio ones are generally medium- to low-skilled subjects that invest part of their capital in a new venture to mitigate a problem of decreasing productivity in their current business. Novice entrepreneurs, on the other hand, are successful, skilled business owners, running a high-quality activity.

We test the predictions obtained from our model using a novel dataset from Vietnam. Two main advantages are associated with the use of this database. First, it enables us to construct various measures for entrepreneurial skills (personal characteristics of the entrepreneur: education, industry experience, managerial experience) and business quality (features of the business: innovation intensity, share of technical and managerial employees) which inherently provide more comprehensive insights. Second, while the majority of the extant research on the topic deals with developed countries, it enables us to address an important research gap by considering the case of a fast-growing transition economy. Coherently with our theoretical model, we prove that more human capital is associated to a higher likelihood to be a habitual entrepreneur. Moreover, a higher quality of the new business is associated with a higher likelihood of being habitual entrepreneurs, which implies that the higher entrepreneurial skills, the larger the impact of an increase in the quality of the new business on the likelihood to be serial or portfolio. Finally, habitual entrepreneurs tend to stay in business longer, while novice entrepreneurs, when endowed with high entrepreneurial skills and a high-quality business, are the category with the lowest probability to leave the market.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a concise overview of the literature on the occupational choices of entrepreneurs. In Section 3, we set up a model of occupational choice and survival that allows to single out the main drivers of serial and portfolio entrepreneurship. Section 4 introduces the hypotheses, based on our model, which are tested in the empirical analysis. Section 5 describes the distinctive features of the entrepreneurial eco-system in Vietnam, and Section 6 introduces the dataset. The econometric strategy is presented in Section 7, whereas Section 8 discusses the results of the empirical analysis. Finally, Section 9 concludes and illustrates possible directions for future research.

2 Literature review

The literature analyzing the occupational choices of entrepreneurs is extensive: many scholars study the choice between entrepreneurship and paid employment, and several investigate the choice between novice and habitual entrepreneurship. However, within this line of research, only a few studies focus explicitly on both serial and portfolio entrepreneurship.

2.1 Entrepreneurship or paid employment?

Two different lines of investigation have studied the choice between entrepreneurship and paid employment: (i) the first one explains entrepreneurial intentions and the tendency to be an entrepreneur from her/his psychological, sociological, and cognitive activities (Katz 1992; Kolvereid 1996; Lazear 2005; Carbonara et al. 2018) which can be genetically inherited (Zhang et al. 2009; Nicolaou and Shane 2010) and are reflected mainly in the willingness to take risk. This approach can be traced back, among others, to Lucas Jr. (1978), Kihlstrom and Laffont (1979), Cramer et al. (2002); (ii) the second one, developed by Kirzner (1979), Schultz (1980), Blanchflower and Oswald (1998), and Baumol (1990), assumes the entrepreneur to be an individual able to capture opportunities and turn them into new products.

Subsequent literature has tried to apply these two approaches to other types of occupational choices besides the fundamental choice between entrepreneurship and paid employment. Contributing to the latter approach, Holmes and Schmitz Jr (1990) build a theoretical model based on the idea that business transfers represent very common resource reallocations serving the purpose of facilitating the division of labor among entrepreneurs. According to their view, serial entrepreneurs are individuals who decide to sell (or shut down) their business if they find that someone else is endowed with a greater ability to pursue the opportunities that business is meant for. Their model is supported by empirical evidence drawn mostly from Pakes and Ericson (1988). On the same line of research, Plehn-Dujowich (2010) finds that, in equilibrium, a highly skilled entrepreneur shuts down a business of low quality to become a serial entrepreneur, whereas a low-skilled entrepreneur shuts down a business of low quality to enter the labor market.

Contributing to the first approach, Åstebro et al. (2011) present and test, using data for Korea, a model in which individuals switching from wage employment to self-employment are more often the most able individuals, who find self-employment more attractive whenever employment with a mismatched firm leads them to earn a poor wage. This occurs since the consequences of such mismatches for wages tend to persist over time, pushing skilled workers to enter self-employment.

Parker (2014) offers an important contribution to the relevant literature by presenting one of the very few theoretical studies on the decision between serial and portfolio entrepreneurship. In particular, the latter is justified by the entrepreneur’s risk aversion, which, in special circumstances, requires portfolio diversification across multiple opportunities.Footnote 5

Turning to the empirical literature, we can find several contributions testing the validity of the two approaches we describe above. Again, very few empirical studies focus on portfolio entrepreneurs explicitly.

2.2 The psychological traits of entrepreneurs

Within the psychological and personal characteristics approach, the existing empirical literature identifies significant differences between novice and habitual entrepreneurs. Specifically, two main factors influence an entrepreneur’s occupational choice: (i) impetus factors (related to personal characteristics and relevant life events) and (ii) situational factors that become relevant once impetus factors have been activated (such as environmental and market changes or organizational performance), affecting her/his perceptions of desirability and feasibility (Dollinger 2008). Such situational factors can be narrowed down to the entrepreneur’s personal background and the quality of the business at the organizational level. Regarding personal background, habitual entrepreneurship is often a by-product of a personal learning and development process, in which habitual entrepreneurs exploit experiences and expertise from the first business and apply them to future businesses.

Starting a second venture indicates the existence not only of professional abilities or entrepreneurial skills, but also “an appropriate psychological mindset, and a belief that entrepreneurship is indeed a preferred career choice” (Barnir 2014, p. 3). Therefore, habitual entrepreneurs are found to be younger when they started their first business (Westhead and Wright 1998), hold a greater amount of human and social capital (Wiklund and Shepherd 2008; Li et al. 2009; Sieger et al. 2011), and have a more diverse experience and more resources (Westhead et al. 2005; Amaral et al. 2011). Focusing on the role of innate ability in serial entrepreneurship, learning by doing is less important than selection on innate ability in explaining both the formation and the early performance of serial businesses. This result is proven by Chen (2013) for a young cohort of U.S. firms between 1979 and 1994 and by Rocha et al. (2015) for a sample of Portuguese firms between 1997 and 2003. Moreover, Chen (2013) finds that the only exception to this empirical regularity occurs when an entrepreneur creates a new firm in an industry closely related to her/his past business experience.

Turning to portfolio entrepreneurship specifically, the existing literature has analyzed the skills developed by serial entrepreneurs, as compared to portfolio ones. Under the framework of the resource-based view of the firm (Penrose 1959), two broad inputs measure business quality: hard inputs (such as financial capital, investments) and soft inputs (such as technological capabilities or technical skills) (Bridge et al. 1998; Westhead et al. 2003). Such inputs are significantly crucial to exploit entrepreneurial opportunities. With respect to soft inputs, while owning multiple businesses simultaneously enables portfolio entrepreneurs to access wider sources of finance and internalize different kinds of technological skills (Wright et al. 1998), owning multiple businesses sequentially allows serial entrepreneurs to enrich their entrepreneurial experience and sharpen their technical expertise. Thus, as a result of prior business ownership experience gained by serial entrepreneurs, and accumulated diverse skills and expertise gained by experienced portfolio ones, habitual entrepreneurs are more able to select the best organizational routines and capabilities oriented toward innovation and business growth (Westhead et al. 2003). Habitual entrepreneurs are then more likely to undertake several innovation activities than to pursue new ventures as a one-time career change (Robson et al. 2012). With respect to hard inputs, portfolio entrepreneurs are able to utilize and leverage the internal financial resources from their existing business(es) to fund their subsequent venture, whereas serial entrepreneurs with a track entrepreneurial record and collateral from the previous business can secure external finance to partly fund a subsequent venture (Westhead et al. 2003). Thus, consistent with Blanchflower and Oswald (1998), it is expected that successful habitual entrepreneurs have larger amounts of investment capital than novice ones who due to the lack of an established track record rely mainly on internal sources of capital (personal savings or loans from family and friends).

One of the main difficulties with empirical studies of portfolio entrepreneurship based on the psychological approach is that the level of analysis needs to be shifted from the firm to the individual whereas the majority of the data are at the firm level. Sieger et al. (2011) suggest that using the firm as the unit of analysis might lead to underestimating the prevalence of portfolio entrepreneurship, since owning and managing multiple businesses could be considered a normal diversification strategy at the firm level. While the goal of strategic diversification is to maximize managerial efficiency or risk management, reasons for engaging in portfolio entrepreneurship may include growth aspirations, wealth, value maximization, and providing career opportunities for family members (Mulholland 1997). Using an interesting approach based on in-depth exploration of a single-case study, Baert et al. (2016) identify three groups of a total of eight resource orchestration subprocessesFootnote 6 that allow potential portfolio entrepreneurs to explore simultaneously numerous market opportunities from which they extract those that are worth exploiting.

2.3 Entrepreneurship and the exploitation of opportunities

We focus now on the second approach that studies the entrepreneurs’ ability to identify and exploit new opportunities and review the empirical literature within that specific approach. Consistent with Holmes and Schmitz Jr (1990), one might wonder whether the process of division of labor among entrepreneurs produces a different business quality for habitual and novice entrepreneurs. Indeed, these strategic occupational choices with associated subsequent hard and soft resources significantly differentiate the business quality of habitual entrepreneurs from that of novice entrepreneurs: businesses owned by habitual entrepreneurs are better in overcoming growing barriers and seeking a long-term competitive advantage. As a matter of fact, indication that habitual entrepreneurs are a high-quality fraction of novice entrepreneurs arises from a conspicuous body of research suggesting the economic outperformance of habitual entrepreneurs (Wright et al. 1998; Westhead and Wright 1999; Klepper and Simons 2000; Åstebro and Bernhardt 2003; Agarwal et al. 2004; Hyytinen and Ilmakunnas 2007; Wiklund and Shepherd 2008; Chen 2013). Comparing the business quality of a portfolio with that of a serial, Westhead et al. (2005) observe, for a sample of 354 firms in Scotland, that portfolio entrepreneurs have more resources and organizational capabilities (skills, knowledge, etc.) than the serial. Besides, on average, they seem to offer more attractive growth prospects. Tihula and Huovinen (2010), focusing their analysis on a sample of 245 Finnish firms with 20–49 employees, provide empirical evidence about the presence of managerial teams in small firms. They distinguish solo entrepreneurs (i.e., entrepreneurs who themselves run the firm that they own) from entrepreneurs who share responsibility with small groups of managers from different functional areas and other key persons (managerial team). Their findings show that solo entrepreneurship is more common among novice entrepreneurs, and there are more management teams in firms owned by portfolio entrepreneurs than in firms owned by serial entrepreneurs.

2.4 The exit decision

Finally, we turn to the reasons that explain the exit of a firm from the market. The huge literature on firm exit (cf. for example, Harhoff et al. 1998; Maertz and Campion 2004; Mason and Harrison 2006; Cumming 2008; DeTienne 2010; Cefis and Marsili 2012; Elfenbein and Knott 2015) has produced a wide range of results some of which are of particular interest for our purposes. Entrepreneurial exit, as defined by DeTienne (2010, p. 213), is “the process by which the founders of privately held firms leave the firm they helped to create; thereby removing themselves, in varying degree, from the primary ownership and decision-making structure of the firm”. As a multilevel phenomenon, entrepreneurial exit can occur in three distinct scenarios: firm exit, founder exit, or exit of both firm and founder (Wennberg et al. 2010; DeTienne and Cardon 2012). DeTienne et al. (2015), p. 1) name these three exit categories as entrepreneurial recycling, entrepreneurial departure, and entrepreneurial culmination, respectively. In this sense, entrepreneurial exit can be the result of both poor and strong performance depending on entrepreneurs’ exit reasons, from poor economic performance to deliberate exit decisions.

DeTienne (2010), p. 209) suggests that three forces explain the termination of the current business: alternative, calculative, or normative. Alternative forces refer to “alternative opportunities” (Maertz and Campion 2004, p. 570) that could be a well-paid job opportunity (become a wage employee) or a new business opportunity (become a serial entrepreneur). Calculative forces refer to the ability of achieving their “goals and values in the future at their current organization” (Maertz and Campion 2004, p. 570). Entrepreneurs consider exit evaluating their current venture’s viability and quality. In case of low market demand, weak technological capabilities, or strong competitive environment, exit might be preferable. Normative forces, on the other hand, refer to the individual’s perception of family or friends’ expectations regarding their business. Entrepreneurs are less likely to close down their business if their relatives and friends have confidence or financial investments in the business. DeTienne et al. (2015, p. 6) construct a typology of exit strategies. They suggest that less educated entrepreneurs with a weak psychological commitment and an insignificant amount of invested resources may recognize that a career in entrepreneurship is demanding and adopt a “voluntary cessation strategy” such as liquidation and discontinuance (Harhoff et al. 1998). On the other hand, those possessing high education and high levels of innovation would apply a “financial harvest exit strategy”, such as selling the business if substantial value accrued to the entrepreneur (Cumming 2008; Cefis and Marsili 2012). DeTienne and Cardon (2012) also find that entrepreneurial education and experience are positively associated with exit through external acquisition, i.e., selling off the business for financial surplus. In summary, although various reasons could explain firm exit, the general consensus is that entrepreneurs possessing lower education and business innovativeness would easily close down their businesses by liquidation (i.e., bankruptcy) while those with higher education and innovativeness would take the same decision if they could sell off their business for financial rewards. The probability of entrepreneurial reengagement after exit is also found to be higher for the latter case (Hessels et al. 2011; Amaral et al. 2011).

3 A model of occupational choice and survival

In this section, we set up the model that we are going to test empirically in the remainder of the paper. Extending the tradition initiated, among others, by Schultz (1980) and Holmes and Schmitz Jr (1990), we develop significant insights for how idiosyncratic individual attitudes and business characteristics may lead entrepreneurs to make occupational choices in the course of their working life. Such insights will then be used to develop testable hypotheses about the qualities and the behavior of novice, serial, and portfolio entrepreneurs.

Each period, entrepreneurs are endowed with a fixed amount K of capital (of at least one unit: K ≥ 1) and produce using a Cobb–Douglas technology. An entrepreneur’s profits are π(q, s) = qKs, where q is the quality of the firm and s is the entrepreneur’s skill. Thus, πs > 0 (higher skills increase profitability) and πq > 0 (higher quality businesses are more profitable). Also, πqs > 0, i.e., entrepreneurial skills and business qualities are complements. Skill affects the marginal productivity of capital and the returns to scale of the entrepreneur’s business. We assume s ≤ 1.Footnote 7

Quality q is distributed according to the distribution function Q(∙) over the interval [0, ∞), whereas ability s is distributed according to the function S(∙) over the interval [0, 1].

Time is discrete and infinite. An entrepreneur maximizes the expected value of the future flow of profits V, where

and 0 < β < 1 is the discount factor.

Suppose that, at time t, an entrepreneur owns a business characterized by quality q. She/he has then four possible options: (1) keep her/his current business (remaining novice); (2) sell or close her/his current business and invest in a new one with expected quality \( \widehat{q} \) (becoming a serial entrepreneur); (3) invest in a new business of quality \( \widehat{q} \) while keeping her/his original one (thus becoming a portfolio entrepreneur); and (4) sell or close her/his current business and leave entrepreneurship, becoming a paid worker.Footnote 8

Define V(q, s) the present value of the future flow of profits for an entrepreneur with skill s, currently owning a firm of quality q who, at time t, decides to keep it (novice)

Similarly, an entrepreneur deciding to start a new business with expected quality \( \widehat{q} \) and leave the current one (serial) gets a present expected value equal to

where τ is the portion of capital the entrepreneur loses when setting up the new firmFootnote 9 and \( \widehat{q}=\underset{0}{\overset{\infty }{\int }} qdQ(q)= Eq \), the expected quality of the new business.Footnote 10

Assume now that the entrepreneur is willing to start a new business, but she/he does not want to shut down her/his current one (portfolio entrepreneurship). She/he therefore invests a fraction γ of her/his resources in the current business and the remaining 1 − γ in the new one, running two businesses at the same time. The present expected value from this occupational choice is \( {V}^P\left(q,s,\widehat{q},\gamma \right)={qK}^s+\beta \frac{q{\left(\gamma K\right)}^s}{1-\beta }+\beta \underset{0}{\overset{\infty }{\int }}\frac{q{\left[\left(1-\gamma \right)\left[1-\tau \right)\Big]K\right]}^s}{1-\beta } dQ(q) \), which can be rewritten as

In practice, at time t, an entrepreneur choosing to become portfolio maximizes the present value \( {V}^P\left(q,s,\widehat{q},\gamma \right) \) dividing her/his available capital between her/his current business and a new one of expected quality \( \widehat{q} \) in order to maximize the present value from this occupational choice, \( {V}^P\left(q,s,\widehat{q},\gamma \right) \).

Define γ∗ the value of γ that maximizes (4), with 0 ≤ γ∗ ≤ 1. Notice that, with the exception of leaving entrepreneurship (option 4 above), all occupational choices descend, as special cases, from the maximization of the function in Eq. (4). In particular, \( {V}^P\left(q,s,\widehat{q},0\right)={V}^S\left(q,s,\widehat{q}\right) \): the present expected value of the profits from portfolio entrepreneurship when no capital is invested in the current business (γ = 0) is equal to the present expected value from serial entrepreneurship. Similarly, \( {V}^P\left(q,s,\widehat{q},1\right)={V}^N\left(q,s\right) \): the present expected value of the profits from portfolio entrepreneurship when all capital is invested in the current business (γ = 1) is equal to the present expected value from novice entrepreneurship. Since γ∗ maximizes \( {V}^P\left(q,s,\widehat{q},\gamma \right) \), it also selects the alternative that yields the highest profit. Thus, the entrepreneur chooses to become a portfolio entrepreneur if 0 < γ∗ < 1, so that she/he will operate both firms. She/he will be a serial entrepreneur if γ∗ = 0, so that she/he exchanges her/his old business for the new one and a novice entrepreneur if γ∗ = 1, in which case she/he stays with her/his current business solely.

The present expected value from the three different occupational choices (novice, serial, and portfolio) can therefore be summarized by a unique equation

where the superscript e stands for “entrepreneurship.”

Finally, defining w the wage the individual earns in each period in paid occupation, the present expected value of leaving entrepreneurship is

Consider now an individual that, at time t, is running a business (this individual could be a novice entrepreneur with her/his first business or a serial who has founded a new business). The timing is as follows: the entrepreneur, who knows her/his skill s and the quality q of her/his current business, decides the optimal share of capital γ∗ to invest in the business (or businesses) she/he will run in the following period. This determines the maximum amount of profits she/he could obtain from her/his entrepreneurial activity. Then, she/he makes her/his occupational choice decision, comparing the best expected outcome as an entrepreneur with employment.

Define \( V\left(q,s,\widehat{q}\right) \) the optimal value of the occupational choice problem for an entrepreneur running a business of quality q with skill s, who has found a new entrepreneurial opportunity with an expected quality \( \widehat{q} \) and has to decide whether to remain novice, launch a new business, or leave entrepreneurship.

The Bellman equation is

To determine the value of the function \( {V}^e\left(q,s,\widehat{q},\gamma \right) \), we need to compute the optimal γ∗, which then defines the type of entrepreneur the individual will be in equilibrium, according to expression (5). The maximization of the value function is then over two occupational choices: entrepreneurship as defined by the optimal γ∗ and paid work. It is therefore a dynamic programming problem that considers the choice between discrete actions.Footnote 11

3.1 The entrepreneur’s choice: novice, serial, or portfolio

Before dealing with the maximization of the value function \( V\left(q,s,\widehat{q}\right) \), we need to characterize the optimal γ∗. To do so, we maximize the present expected value in expression (4) with respect to γ. The following propositions contain our results.Footnote 12

- Proposition 1.

If s < 1, the entrepreneur keeps a share 0 < γ∗ < 1 of the available capital in the old business but invests the remaining share 1 − γ∗in the new one, becoming a portfolio entrepreneur. The optimal share γ∗is increasing in q and τ, decreasing in\( \widehat{q} \). It is also increasing in s when\( \frac{\widehat{q}}{q} \)is large and τ small.

Notice that the entrepreneur chooses to invest in a portfolio of enterprises irrespective of the qualities of the old and the new enterprise, q and \( \widehat{q} \). When s < 1, capital is not very productive: its marginal productivity is small and decreasing. Transferring some capital from the old to the new business increases productivity, both for the units remaining in the old business and for those in the new one. Intuitively, the optimal share γ∗ is larger when q is large: the higher the quality of the current business, the larger the investment the entrepreneur is willing to maintain in that activity. Similarly, the larger the expected quality of the new business \( \widehat{q} \), the bigger the desired investment in it.

The results in Proposition 1 imply also that the higher \( \frac{\widehat{q}}{q} \) and the greater the entrepreneur’s ability s, the bigger the share of capital invested in a new business. In fact, as s increases, the less important is the role of the marginal productivity of capital in the entrepreneur’s decision and the more she/he tends to invest in the best business opportunity (in this case, the new enterprise), being the need to diversify less compelling. Vice versa, when \( \frac{\widehat{q}}{q} \) is small, γ∗ tends to increase with s, thus the share of capital left in the current business is larger, since, in this case, that is the best opportunity.

- Proposition 2.

If s = 1, the entrepreneur chooses to dispose of her/his original business and to invest all her/his capital in a new enterprise if and only if\( \widehat{q}>\frac{q}{1-\tau } \), becoming a serial entrepreneur.

The intuition is straightforward: being s = 1, this case presents a constant marginal productivity of capital on either activity. The entrepreneur’s occupational choice is therefore driven only by relative business quality and by the cost of setting up the new business.Footnote 13

3.2 Entrepreneurial exit

We can now proceed to the maximization of the value function in (7) over the two occupational choices: entrepreneurship as defined by the optimal γ∗ and paid work. In order to decide whether to remain entrepreneurs or to take a paid job, individuals compare their equilibrium choice as entrepreneurs (novice, serial, and portfolio), with the present value of their outside option (e.g., earnings as a paid employee).

Our goal in this section is to study entrepreneurial exit (or survival). In this paper, we follow the definition provided by DeTienne (2010) and reported in Section 2.4 above. Thus, entrepreneurial exit, in our model, is determined both by entrepreneurs leaving entrepreneurship and taking a paid job and by serial ones, who “leave the firm they helped to create” to start a new one.Footnote 14

Propositions 1 and 2 above have proven that the entrepreneur chooses to run a portfolio of businesses if s < 1 and chooses to be either novice or serial if s = 1, depending on the relative quality of her/his current and prospective businesses.

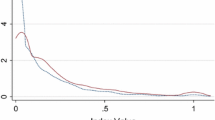

Consider first the case in which s < 1. In this case, serial entrepreneurship is ruled out. We focus therefore on the choice of leaving entrepreneurship. Figure 1 graphs the value function (7) and shows that the entrepreneur “survives” (i.e., she/he maintains her/his job as an entrepreneur) if \( \widehat{q}\ge {\widehat{q}}^P \) and exits (going back to paid work) if \( \widehat{q}<{\widehat{q}}^P \), where \( {\widehat{q}}^P \) is the value of \( \widehat{q} \) (the quality of the new business) at which the individual is indifferent between being an entrepreneur and getting a paid job.Footnote 15 Looking at Fig. 1, one should notice that \( {\widehat{q}}^P \) increases with w and decreases with q (the quality of the original firm). In fact, an increase in w shifts \( {V}^P\left(q,s,\widehat{q},\gamma \right) \) up, moving the intersection point to the right, whereas an increase in q moves up both \( {V}^P\left(q,s,\widehat{q},\gamma \right) \) and Vw(q, s, w), but \( {V}^P\left(q,s,\widehat{q},\gamma \right) \) moves to a greater extent. If we define \( {\psi}^P={\int}_0^{{\hat{q}}^P}\mathrm{d}Q\left(\hat{q}\right) \) the probability that the portfolio entrepreneur leaves entrepreneurship, the greater \( {\widehat{q}}^P \), the higher ψP. Intuitively, the mean survival time of a business is negatively related to the probability of exit. Thus, unsurprisingly, a portfolio entrepreneur tends to “survive” longer the better the quality of the firms in her/his portfolio and the lower the value of the outside option, w.

Consider then the case with s = 1. In this case, entrepreneurial exit can be determined by both leaving entrepreneurship and transferring a firm to start a new one. We concentrate first on the choice to leave entrepreneurship. From Proposition 2, if \( q\ge \widehat{q}\left(1-\tau \right) \), the entrepreneur would be novice. Comparing VN(q, s) with Vw(q, s, w), we can see that the entrepreneur exits if \( q\le {q}^N=\frac{w}{K} \). Defining \( {\psi}^N={\int}_0^{q^N}\mathrm{d}Q(q) \) the probability that the novice entrepreneur exits, we can conclude that the mean survival time of a business run by a novice entrepreneur depends negatively on w and positively on its size K. Similarly, if \( \widehat{q}\ge \frac{q}{1-\tau } \), the entrepreneur would be serial. Comparing \( {V}^S\left(q,s,\widehat{q}\right) \) with Vw(q, s, w), we can see that the entrepreneur exits if \( \widehat{q}\le {\widehat{q}}^S=\frac{w}{{\left(1-\tau \right)}^sK} \). Their exit probability is \( {\psi}^S={\int}_0^{{\hat{q}}^S}\mathrm{d}Q\left(\hat{q}\right) \). Once again, the mean survival time of a business run by a novice entrepreneur depends negatively on the value of their outside option and on τ, and positively on capital.

Following DeTienne (2010), we need to include in survival also firm transfers of entrepreneurs that continue in their entrepreneurial role. In our model, entrepreneurs that can transfer or shut down their businesses (not leaving entrepreneurship) are novice starting a new business and becoming serials. This happens when \( {V}^N\left(q,s\right)<{V}^S\left(q,s,\widehat{q}\right) \), i.e., when \( q\le {q}^{\prime }=\widehat{q}\left(1-\tau \right) \). In order for a novice to survive (in the sense that she/he keeps her/his original business), it must be q > max {q′, qN}: the quality q of her/his current enterprise must be high enough to render keeping it more attractive than both starting a new firm and leaving entrepreneurship.

If q′ < qN, the probability that a novice “survives” is 1 − ψN. If q′ > qN, the probability of survival is \( {\mu}^N=1-{\int}_0^{q\prime}\mathrm{d}Q(q) \), which is positively influenced by q and by τ.

We are now going to address the following questions: (1) Which type of entrepreneur has the highest probability to stay in entrepreneurship? (2) Which type of entrepreneur (novice, serial, portfolio) survives longer?

In dealing with question 1, we keep our assumption s ≤ 1. In this range, we know from Propositions 1 and 2, that, at γ∗, \( {V}^P\left(q,s,\widehat{q},{\gamma}^{\ast}\right)\ge \max \left\{{V}^N\left(q,s\right),{V}^S\left(q,s,\widehat{q}\right)\right\} \). Figure 2a plots the present values of the profits for portfolio and serial entrepreneurs and for paid work against the quality of the future business \( \widehat{q} \) (the value for novice entrepreneurs does not depend on \( \widehat{q} \) and will be compared separately). Portfolio entrepreneurs exit if \( \widehat{q}\le {\widehat{q}}^P \), whereas the serial exit if \( \widehat{q}\le {\widehat{q}}^S \). Figure 2a shows that \( {\widehat{q}}^P<{\widehat{q}}^S \), which implies, by definition, that ψP < ψS. In general, the probability that portfolio leave entrepreneurship cannot be higher than the probability that serial exit. Therefore, the expected “survival” time (which, in this case, means time in the entrepreneurial role) is higher for portfolio entrepreneurs than for serial ones. Similarly, Fig. 2b compares the expected values of profits of portfolio and novice entrepreneurs and for paid work (this time plotted against the quality of the current business q). All functions are now increasing in q. Figure 2b shows clearly that the exit threshold for portfolio entrepreneurs is lower, so that their expected “survival” time is again longer.

Consider now serial and novice entrepreneurs. Comparing qN and \( {\widehat{q}}^S \) (i.e., the quality thresholds that determine exit and survival of firms led by novice and serial entrepreneurs respectively), it is immediate to see that \( {q}^N<{\widehat{q}}^S \), so that, being q and \( \widehat{q} \) drawn from the same distribution, novice face a smaller probability of leaving entrepreneurship than serial. However, this is not enough to conclude that the survival time is longer for novice, since novices can “exit” also by becoming serial. In particular, if q′ > qN, it may well be then that \( {q}^{\prime }>{\widehat{q}}^S \), in which case the survival time would be longer for serial entrepreneurs. This is all the more likely if τ is small, if serial entrepreneurs have a larger endowment of capital K or a very good prospective profitability of the new enterprise, \( \widehat{q} \).

As for the impact of skill s on survival time, from our model, it follows that a novice is a highly skilled entrepreneur owning a very good business, while a serial is a highly skilled entrepreneur facing an extremely good new opportunity, so that she/he can face the cost τ of setting up a new business. A portfolio entrepreneur is a low to averagely skilled individual mitigating a problem of scarce productivity in her/his original enterprise through diversification.

Therefore, as long as good quality and high skill induce a high probability of survival, novice entrepreneurs have the highest chances to survive, i.e., to continue as entrepreneurs.

4 Hypotheses

Given our results on the impact of the characteristics and the behavior of novice, portfolio, and serial entrepreneurs, we are now able to formulate the hypotheses that we are going to test in the empirical part of the paper. From our theoretical model, we infer that, ceteris paribus:

- 1.

Entrepreneurs tend to remain novice (i.e., continue to run their current businesses) when they are highly skilled (s = 1), and the quality of their current businesses is high (q ≥ (1 − τ)\( \widehat{q} \)). Taking into account that divesting capital from a business and reinvesting it in a new one is costly (τ), it might happen that \( q<\widehat{q} \) and still the entrepreneurs prefers to retain her/his original firm.

- 2.

Serial entrepreneurs are highly skilled entrepreneurs (s = 1) who get a new opportunity of higher quality than their current business, so that it is convenient for them to seize the new opportunity notwithstanding the setup cost (\( \widehat{q}\ge \frac{q}{\left(1-\tau \right)} \)).

- 3.

Portfolio entrepreneurs are low- to medium-skilled entrepreneurs (s < 1), running businesses of both high and low quality.

- 4.

A higher quality of the new business (\( \widehat{q} \)) increases the likelihood that the entrepreneur is habitual (either serial or portfolio).

- 5.

The higher the entrepreneurial skills, the larger the positive impact of an increase in the quality of the new business on the likelihood to be a serial entrepreneur.

- 6.

For given skill, a portfolio entrepreneur faces a longer “survival” time than her/his serial and novice counterparts.

- 7.

A highly skilled novice entrepreneur with a high-quality business is more likely to keep her/his current business than a habitual one.

Based on the results above, we can formulate the following hypotheses, which we are going to test in our empirical analysis.

From results 1 and 2, we get our first hypothesis.

H1: High entrepreneurial skills and high quality of new business opportunity are more likely to be associated to habitual entrepreneurship (serial and portfolio).

Results 3, 4, and 5 yield our second hypothesis.

H2: A higher quality of the new business is associated to a higher likelihood of being habitual entrepreneurs (serial and portfolio).

Particularly, the higher the entrepreneurial skills, the larger the positive impact of an increase in the quality of the new business on the likelihood to be a habitual entrepreneur.

Finally, results 6 and 7 yield our third and last hypothesis.

H3: Firms run by portfolio entrepreneurs face the longest survival time and those run by serial survive longer than those run by novice. The combined effect of high entrepreneurial skills and good-quality business makes firms run by novice entrepreneurs to have the lowest likelihood to exit.

5 An overview of the empirical setting—Vietnam

The transition of Vietnam to a market economy has been characterized by the emergence of a strong entrepreneurial ecosystem (Ronnås and Ramamurthy 2001). Accordingly, this highly entrepreneurial country represents an ideal laboratory for testing the predictions of our model.

Vietnam formally started its successful transition to a market economy at the end of 1986 with the adoption of a “reform and open-door policy.” During the transition, its GDP grew constantly, with a growth rate that was 3.4% in 1986 and reached a peak of 9.5% in 1995. After a sudden decline in 1999 (5%), the economy regained its growing momentum (back to 8.4% in 2005) and has been keeping an average growth rate of around 8% per year since. After joining the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1995, liberalizing trade with the USA in 2001, and becoming a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2007, Vietnam is nowadays a fully integrated member of the international business community.

Throughout the entire transition process, the development of entrepreneurship was supported by significant institutional changes, including the creation of a pro-entrepreneurship legal framework and the promotion of market-oriented productive capabilities (Nguyen et al. 2008; Nguyen and Mort 2016; World Bank 2009). Initially, Vietnam maintained state entrepreneurship while developing private entrepreneurship. Privately owned enterprises (POEs) were first created to perform simple economic activities and then spread into the complex production processes previously dominated by SOE.Footnote 16 Immediately after the enactment of the Law on Foreign Investment in 1988, foreign entrepreneurship started to emerge and took off during the “foreign investment boom” period in 1991–1995. These processes led to changes in the quantity and qualities of entrepreneurship of each type.

The result of the process described above is that Vietnam is characterized by a multifarious and rich entrepreneurial ecosystem, comprising firms of all sizes in many different sectors. Entrepreneurs have the most diverse background (coming from the management of previous SOEs or being self-employed start-uppers of microfirms) and possess a wide range of skill, experience, and human capital (Nguyen et al. 2008; Nguyen and Mort 2016; Santarelli and Tran 2013; Tran and Santarelli 2014). Therefore, Vietnam provides an excellent domain to explore the occupational choices of such a diverse and varied group of entrepreneurs and allows us to conduct our empirical analysis controlling for a wide set of characteristics, both at the individual and at the firm level.

6 Data description

Our analysis uses data from five waves of the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA) surveys (carried out in 2002, 2005, 2007, 2009, and 2011), providing detailed information on various aspects of entrepreneurs and their firms. These surveys stemmed from the collaboration of the Central Institute for Economic Management (CIEM) in Hanoi, Vietnam, and the Ministry of Labor, Invalids and Social Affairs of Vietnam, the Department of Economics of the University of Copenhagen, and the Royal Embassy of Denmark in Vietnam. The surveys are designed with the objective of collecting and analyzing data representing the entire private sector in Vietnam. This means that not only large or formally registered enterprises are interviewed, but also a substantial number of nonregistered household/family businesses are studied in order to gain a comprehensive understanding of firm dynamics in Vietnam.

Despite being carried out at different points in time, all the surveys use the same questionnaire. Further, the analysis of the development of the studied enterprises is possible when they are traced and followed up over time. The 2011 study made use of the sample collected from the 2009 survey which in turn was a follow-up of the 2007 one, and so on. Each survey round provides financial information and economic data from the two most recent years. Thus, in aggregate, this yields an unbalanced 10-year panel dataset, registering also the entry of new firms and the exit of existing ones. The dataset contains a wide range of variables on the demographic characteristics of entrepreneurs, their technological and organizational capabilities, and the economic performance of their firms (for a comprehensive understanding of the surveys, see Rand and Tarp 2007).

Although the surveys are conducted at the firm level, they provide information about current entrepreneurs/owners and their past occupational choices. Since we concentrate precisely on the occupational choices of entrepreneurs, we focus on individuals rather than firms. In particular, we study the owners, rather than the managers of the firms, since it is the owner who is fully responsible for the decisions of maintaining, closing, or expanding the businesses. Our extracted sample consists of 18,850 observations covering 4508 entrepreneurs. Table 1 documents the survival rate of entrepreneurs to link the five surveys in our sample.

The sample includes 3156 novice entrepreneurs (70%), 225 portfolio entrepreneurs (5%), and 1127 serial entrepreneurs (25%). Appendix 2 (Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10) presents and interprets some descriptive statistics and statistical tests for the difference in age, education, firm age, and legal ownership for the novice, serial, and portfolio entrepreneurs in the sample. No statistically significant differences were found among the three groups with respect to their main industrial activity. Regarding geographical location, habitual entrepreneurs mainly locate in urban cities with an abundance of business opportunities, whereas novice entrepreneurs are evenly distributed across provinces.

Information on entrepreneurial exit is obtained by tracing a firm across different survey waves. We can observe when a firm shuts down (entrepreneurial culmination) or changes ownership (entrepreneurial departure). But since we are not able to tell what happens to the exiting entrepreneur (whether she/he moves to paid employment, starts another business or retires), we cannot observe entrepreneurial recycling. Thus, an entrepreneurial exit is noted when the entrepreneur declares in the survey that either the business had been shut down or there is a change in ownership.Footnote 17

7 Econometric strategy

To test the hypotheses listed in Section 4 empirically, we make use of two different equations. In particular, we test hypotheses H1 and H2 (i.e., what leads the entrepreneur to become a serial or a portfolio entrepreneur given her/his entrepreneurial skills, the quality of her/his current business and its financial conditions) using a multinomial logit. We include the interaction of skill and quality in the model, to analyze their interplay.

To test hypothesis H3 (survival), we employ a survival equation, by means of which we investigate what leads a novice entrepreneur to close her/his business given her/his entrepreneurial skills, the quality and the financial conditions of her/his current business. Particularly, looking at the three-way interaction term between “being a novice,” “entrepreneurial skills,” and “current business quality,” we can determine whether a low- or averagely skilled novice entrepreneur facing a low-quality business will close down her/his business, while one facing a high-quality business will keep it alive.

7.1 Methodology

7.1.1 Testing H1 and H2: the occupational choice equation of novice entrepreneurs

Given that we look at the choice of leaving entrepreneurship with the survival equation, here the occupational outcome yi for a novice entrepreneur i is one of the three occupational alternatives (continue to be a novice entrepreneur, become a serial entrepreneur, or become a portfolio entrepreneur). We set yi = j if the outcome is the jth alternative, j = 1, 2, …,3. The probability that the outcome for entrepreneur i is alternative j, conditional on her/his entrepreneurial skills (si), on the business quality (qi) and the initial capital investment (Ki) of her/his current business is

where different functional forms of Fj(.) correspond to different multinomial models. In line with a great deal of papers addressing similar issues, we apply the multinomial logit model.

7.1.2 Testing H3: the survival of novice entrepreneurs

We define a variable time, measuring the time from the first year in which the entrepreneur is surveyed until “death” (i.e., when entrepreneurs exit entrepreneurship, closing down the business or transferring the ownership to another entrepreneur). Obviously, our 10-year study is not a time span long enough to observe the death of all the entrepreneurs in the sample, and thus, our data are right censored. The variable exit is an indicator of whether time refers to business close-down or ownership change (value 1) or end of study (value 0). The survival time T may be regarded as a random variable with a probability function U(t) and probability density function u(t). The survival function or survival curve S(t) is given by:

A further function of interest for survival data is the hazard function. It represents the instantaneous failure rate, i.e., the probability that an entrepreneur experiences the event of interest (exit) at a particular point in time, given that the event has not yet occurred. The hazard function is given by \( h(t)=\frac{f(t)}{S(t)} \). Combining it with (9), we have \( -\frac{\mathrm{d}\mathrm{log}\left(S(t)\right)}{\mathrm{d}t}=h(t) \), so that S(t) = exp(−H(t)), where H(t) is the integrated hazard function, or cumulative hazard function.

We deploy four different estimation modelsFootnote 18: the nonparametric Kaplan–Meier estimator, the semiparametric Cox proportional hazards regression, the parametric Weibull model, and the discrete-time survival model (logit model).Footnote 19 We use observations on all the 4508 entrepreneurs in the sample, singling out novice entrepreneurs by means of the dummy variable Novice (taking value 1 when the entrepreneur is a novice and 0 otherwise).

7.2 Variables

7.2.1 Independent variables

Categories of entrepreneurs

A categorical variable presenting different, mutually exclusive occupational choices for an entrepreneur. The variable attains value 0 if the entrepreneur is a novice, 1 if she/he is a serial entrepreneur and 2 if she/he is a portfolio. Serial entrepreneurs are those who answered “yes” to the question “before establishing the present enterprise, did you own any other enterprise?”. Portfolio entrepreneurs are those who answered “yes” to the question “does the owner currently have more than one enterprise?”Footnote 20

Serial entrepreneur/portfolio entrepreneur

Dummy variables respectively attaining value 1 if the individual is either a serial or a portfolio entrepreneur, and 0 otherwise.

The following two variables enable us to set the survival time.

Entrepreneurial exit is an event variable. It is a dummy variable that attains value 1 if either the entrepreneur shuts down the business or leaves the business (change in ownership), and 0 otherwise.

Time is the duration variable. It measures the duration in years from the starting year of the firm (when the firm was established) until she/he closed it down or transferred ownership (if that is the case during our observation period).

7.2.2 Explanatory variables

Based on the model presented above, we introduce three groups of explanatory variables:

- (1)

Entrepreneurial skills sit, proxied by the following four variables, measuring human capital characteristics: (i) education is the number of schooling years for each entrepreneur. (ii) Industry experience is a dummy taking value 1 if the entrepreneur has previously worked in the industry and has prior knowledge of buyers and suppliers, and 0 otherwise. (iii) Management experience is a dummy taking value 1 if the entrepreneur has worked in a managerial position previously, and 0 otherwise. (iv) Labor force experience is a dummy taking value 1 if the entrepreneur has previously worked as a paid employee, and 0 otherwise. The rationale for adopting these proxies to reflect entrepreneurial skills results from extensive studies supporting the importance of human capital factors in boosting entrepreneurial alertness and performance (among others, Gimeno et al. 1997; Westhead et al. 2005; Bosma et al. 2004; Poschke 2013; Santarelli and Tran 2013; Sorgner et al. 2017).

- (2)

The quality of the firm qit, proxied by its technological and organizational capabilities and measured by the following three variables: (i) innovation intensity is the ratio of the investment on innovation activities to the total annual revenue of the firm. (ii) Share of technical employees in the total labor force is the ratio of the number of technical and R&D employees to the total number of employees of the firm. (iii) Share of managers in the total labor force is the ratio of the number of employees in managerial positions to the total number of employees of the firm.Footnote 21 The rationale for adopting these three proxies could be originally traced back to the resource-based view of the firm (Penrose 1959) suggesting that the quality of a firm results from unique attributes of its competitive resources. Following Bridge et al. (1998) and Westhead et al. (2003), we value business quality from two broad inputs: hard inputs, i.e., investment into innovation activities, and soft inputs, i.e., technological and managerial knowledge and expertise.

- (3)

Total capital Kit in each year, proxied by the logarithm of the total assets of the firm. Three variables will be adopted to measure the capital investment of the entrepreneur: (i) firm size is the economic size of the firm, measured by the logarithm of the total assets of the firm. (ii) Debt ratio, measured by the ratio of total debt to total assets and isolates the effect of a firm’s leverage capacity on its performanceFootnote 22; and (iii) land ownership is a dummy taking value 1 if the entrepreneur owns the land housing the firm’s main production facility, and 0 otherwise.Footnote 23

To study the interaction effect of entrepreneurial skills and business quality, we construct two composite indices measuring entrepreneurial skills and business quality, respectively. For entrepreneurial skills, the composite “skill” index is the sum of four dummies: an “education” dummy attaining 1 if the entrepreneur has high education (technical college, undergraduate, or graduate degrees), 0 if she/he has low education (no education, secondary/high school education); the “industry experience” dummy, the “managerial experience” dummy, and the “labor force experience” dummy described above. This “skill” index ranges from 0 (low education, no experience of any type) to 4 (high education, possessing all industry, managerial, and labor force experience).

The composite “quality” index is the sum of three dummies: “innovation intensity,” “technical share,” and “managerial share” dummies. These dummies attain value 1 if the firm’s respective measure is higher than the third quartile of the sample and 0 otherwise. The “quality” index ranges from 0 (the firm’s innovation intensity, technical share, and managerial share are all below the sample median values) to 3 (all innovation intensity, technical share, and managerial share are all above the third quartile values). Interaction terms are created using these two composite indices.

7.2.3 Control variables

Besides age, gender, and tenureFootnote 24 of the entrepreneur, we include firm age, the age of the current firm. We then isolate the ownership type of the current firm, creating dummies private firms, partnership/cooperatives, limited liability (all taking value 1 when the firm takes the corresponding ownership type and 0 otherwise). Finally, a dummy is added to take any divergence or mismatch arising from different surveys into account.

8 Estimation results

Appendix 3 (Table 11) presents the descriptive statistics and pairwise correlation matrix of all the adopted variables. The average exit rate of firms is about 15%, which is relatively low compared to other studies about Vietnam (e.g., Vijverberg and Haughton 2002). On average, our sampled entrepreneurs are 45 years old and have spent more than 11 years in education.Footnote 25 We can see from the pairwise correlation matrix, out of 136 pairwise correlations, 80 are statistically significant at 1% significance level. However, most of them are very small with correlation coefficients below 0.3. The only two pairwise correlations that are greater than 0.3 are as follows: (i) the one between debt ratio and investment capital (0.43), which indicates that external loans are an important source of finance for our entrepreneurs’ investments, and (ii) the correlation between education and firm size (0.318), which suggests that highly educated entrepreneurs are better in attracting financial resources.

8.1 The occupational choice equation

Table 2 presents the results of the occupational choice model when “novice entrepreneur” is used as the base category. Regressors are jointly statistically significant at the 1% level across the two treatments we estimate. Particularly, the second model (presented in the last two columns) includes the interaction term between the entrepreneur’s skills and her/his current business quality.

In general, entrepreneurial skills have a significantly positive effect on the propensity to engage in habitual entrepreneurship. Education, industry experience, and managerial experience all increase the propensity of an occupational transition to habitual entrepreneurship, and this effect is consistent for both serial and portfolio entrepreneurs. They are more likely to spend longer years in education, possess richer experience from the industry, and have worked previously as managers.Footnote 26 For instance, if the entrepreneur were to increase her/his schooling years by 1 year while holding all other variables in the model constant, the multinomial log-odds for serial entrepreneurs relative to novice would increase by 0.052 units, whereas those for portfolio relative to novice would increase by 0.084 units. This result seems to be quantitatively similar for serial and portfolio individuals. Maybe, qualitatively, we can see a better significance for serial (all three indicators are significant at the 1% level, whereas only two are significant at the 1% level for portfolio, while managerial experience is significant at 5% only). Overall, however, our hypothesis H1, according to which high entrepreneurial skills are more likely to be associated to habitual entrepreneurship (serial and portfolio), is strongly supported.

Previous experience as a paid employee has a negative impact on the entrepreneur’s motivation to take further entrepreneurial risks rebuilding a failed business or expanding their current one.

With respect to the effect of organizational quality on the likelihood of engaging in habitual entrepreneurship, the impact of innovation intensity is not statistically significant. We also allowed for a nonlinear relationship by including its squared value in the regression, but this did not affect the result. The share of technical employees in the total firm labor force exerts a significant and positive impact for both serial and portfolio entrepreneurs. However, the share of managerial employees exerts opposite influences on serial and portfolio entrepreneurship: an increase in managerial employees has a positive impact on portfolio, but a negative impact on serial entrepreneurship. An increase in managerial expertise, while enabling portfolio entrepreneurs to manage and allocate resources efficiently among old and new businesses, seems to be an impediment to serial entrepreneurs’ agility in exploiting new business opportunities. Thus, the first part of hypothesis H2, stating that a higher quality of the new business is associated to a higher likelihood of being habitual, is confirmed. The effect seems to be stronger for portfolio. In fact, three out of three proxies for business quality exert a positive impact on the likelihood to be portfolio, whereas only two proxies (innovation intensity and technical resources) exert a positive effect on the likelihood to be serial.

Unsurprisingly, the interaction between entrepreneurial skills and business quality in columns 3 and 4 is positive and statistically significant for both serial and portfolio entrepreneurship. Holding other factors in the model constant, a high skill combined with a high-quality business increases the multinomial log-odds to be a serial entrepreneur by 0.065 units, and to be a portfolio by 0.113 units. These findings support the second part of hypothesis H2, proposing that high entrepreneurial skills combined with high business quality are positively associated with the likelihood of being a habitual entrepreneur.

Regarding the impact of investment capital K, we consistently find a positive but almost zero effect on the probability to be habitual. This is consistent with our model, where capital does not play a direct role in the entrepreneur’s occupational choice. Land ownership has a negative effect on the likelihood of being serial but a positive effect on the likelihood of being portfolio. Owning the land housing the main production facility would deter the motivation to relaunch a new venture to reap short-term profit opportunities, since owners can rent out the land they own to substitute for their entrepreneurial income. However, land ownership is favorable to business expansion for portfolio entrepreneurs. They can exploit different entrepreneurial opportunities on the land they own without any concerns for the rent or leasing-related risks. The statistically significant and positive parameters of the debt ratio in the portfolio equations indicate that indebted entrepreneurs are more likely to become portfolio since they can use their leverage conditions to undertake other profitable but risky investments.

With respect to control variables, while the current firm of serial entrepreneurs is larger in terms of the size of firm labor force than the one of novice counterparts, portfolio entrepreneurs have relatively smaller-sized firms, possibly because they own and run multiple businesses. The effect of firm size is however nonlinear. There is a consistent finding that younger firms and younger entrepreneurs are more likely to be habitual (but the effect is insignificant for serial entrepreneurs). Male entrepreneurs are more likely to take risks in expanding the current business (and thus become portfolio entrepreneurs), whereas female are more flexible and adaptive in learning from past failures to relaunch a new business (and thus become serial entrepreneurs). Serial entrepreneurs tend to have shorter tenure and portfolio ones have longer tenure in running their current businesses. Finally, the businesses of serial entrepreneurs are more likely to be private or limited liability companies, whereas portfolio entrepreneurs do not seem to favor any specific ownership type.

8.2 The survival equation

We acknowledge the limitation that we cannot fully confirm the exit of individual entrepreneurs, since the code to trace the survival of observations is at the firm level. Thus, the survival of entrepreneurs is mainly reflected by the survival of their firms. Nevertheless, the survey has a question on the likelihood of a change in ownership, so we can also observe owner exit even if her/his firm is still in operation. In other words, an entrepreneurial exit in our study means (i) the entrepreneur shuts down the business or (ii) she/he transfers the business (e.g., selling or retiring). This is in line with the definition of entrepreneurial exit by DeTienne (2010).

Figure 3 presents different graphs for the nonparametric estimation of firm survival in the sample. In Fig. 3a, the exit rate increases sharply for the first 4 years in business, then it is steadily flat around 4 years before falling sharply after 4 years. In other words, after 4 years remaining in their business, entrepreneurs are significantly less likely to close down their business. The Nelson–Aalen estimator in Fig. 3b serves to obtain the cumulative hazard function by summing up the values of the hazard functions over time. The Kaplan–Meier survival curve (Fig. 3c) presents the survival duration of the sample. It starts from 1 because we have the full sample of firms at the beginning. Over time, they gradually exit the market, thus the curve steps downwards. There are around 75% of firms which are still in business after 2.5 years. After 6 years, this figure reduces to 25%. These findings confirm an empirical regularity largely supported in the relevant literature (cf. among others, Audretsch et al. 1999).

Figure 3d presents the survival curves for businesses of novice, serial, and portfolio entrepreneurs, respectively. A test for the equality of the survival functions for the three groups of businesses rejects the null hypothesis of equality at 1% significance level.Footnote 27 The survival estimates for businesses of serial entrepreneurs are slightly longer than those of novice ones. Portfolio entrepreneurs, on the other hand, remain in their businesses much longer than their counterparts do. Nearly 75% of the portfolio entrepreneurs are still in business after 6 years. These findings confirm the first part of our hypothesis H3 (portfolio entrepreneurs face longer survival time). Moreover, the difference between serial and novice is small and serial tend to survive longer. The longer survival time of serial entrepreneurs could be due to the very high quality of the firm run by a serial entrepreneur or by her/his larger endowment of capital, in line with our Hypothesis H3. Estimates in Section 8.1 have shown that habitual entrepreneurs tend to be associated to high business quality, although they do not seem to be systematically associated to higher capital investment than novice.

Table 3 presents the estimation results of the semiparametric Cox model, the parametric Weibull model, and the discrete-time survival model. We present the results of the first 2 models in two specifications: coefficients (log hazard ratios) and exponentiated coefficients (hazard ratios). Results are generally quite consistent across models.

Ceteris paribus, habitual entrepreneurs remain in their business longer than novice ones do. Regarding entrepreneurial skills, while the length of education is significantly and negatively associated with an entrepreneur’s propensity to shut down their business, industry experience and management experience are surprisingly found to stimulate entrepreneurs to close their business sooner than their unexperienced peers. In particular, from the Cox model, compared to inexperienced entrepreneurs, those having industry experience may exit entrepreneurship at twice the hazard rate per unit time, or those with managerial experience will have higher hazard rate about 1.2 times.

To test the last part of Hypothesis H3, we consider the three-way interaction among entrepreneurial skills, firm-level business quality, and the likelihood of being novice entrepreneurs. The statistically significant and negative parameters of the interaction across all methodological treatments indicate that, ceteris paribus, novice entrepreneurs have a stronger motivation to remain in their business if they have both high entrepreneurial skills and high business quality. However, considering the two-way interactions among our three interested variables, we find some influential results: (i) novice entrepreneurs being endowed with higher skills can maintain their business longer; but (ii) novice entrepreneurs owning high-quality business are more likely to exit the market; and (iii) highly skilled entrepreneurs unsurprisingly have no reasons to exit entrepreneurship if they own a high-quality business. In order to find statistical pieces of evidence to either support or reject our Hypothesis H3, we analyze marginal effects of a novice entrepreneur exiting entrepreneurship at two specific values of entrepreneurial skills and business quality that are one standard deviation above the mean and one standard deviation below the mean. We consistently find the negative and statistically significant relationship between being novice entrepreneurs with high skills and high business quality (one standard deviation above the mean) and exit rate. Therefore, when owning a good-quality business, novice entrepreneurs with high entrepreneurial skills are less likely to exit entrepreneurship, which is exactly our Hypothesis H3.

Our survival analysis yields other interesting results. The technological quality of the firm plays a negative role in sustaining its survival. The hazard rate is almost 2.1 times higher for entrepreneurs with larger technological resources (Cox model). The relationship between innovation intensity and the likelihood of survival is not necessarily positive, given that innovative firms tend to incur high sunk costs from large R&D investments and operate in a very competitive market portions where the innovativeness of rivals might be even greater than theirs.

Another noteworthy finding is the consistent, negative, and nonlinear effect of capital investment on firm exit (although not economically strong). Other things kept constant, more initial investment capital leads to higher survival propensity; but once an optimal level of investment capital is reached, a further increase in investment does not lead to a proportional increase in entrepreneurial survival.

Finally, heavily indebted entrepreneurs have a lower propensity of survival and larger (in terms of labor force) and younger firms are more vulnerable to bankruptcy, while older entrepreneurs seem to survive longer.Footnote 28

9 Conclusions

We studied why some entrepreneurs become serial or portfolio while others remain novice. We propose a theoretical model illustrating the occupational choice of a novice entrepreneur, given her/his entrepreneurial skills, the quality of the current business and the expected quality of the prospective future business. In equilibrium, an entrepreneur maintains her/his business if she/he is highly skilled and the business is sufficiently profitable. Highly skilled individuals tend to become serial entrepreneurs when they encounter a very profitable new opportunity. If skill is either low or medium, they tend to become portfolio entrepreneurs to mitigate the scarce productivity of their first business. While novice and serial entrepreneurs generally own good-quality firms, portfolio entrepreneurs can run both high- and low-quality businesses.

We also analyzed the interaction between entrepreneurial skills and the quality of the new business of a habitual entrepreneur. We prove that a high quality of the new business (measured in terms of innovation intensity and share of technical and managerial employees in total employment) increases the likelihood that the entrepreneur becomes habitual and that such a positive impact tends to be larger for portfolio entrepreneurs. Moreover, due to the complementarity between skills and firm quality in the profit function, the higher the entrepreneurial skills are, the larger is the positive impact of an increase in the quality of the new business on the likelihood to be a habitual entrepreneur. Finally, a highly skilled novice entrepreneur facing a good-quality business tends to keep it.

Testing the relevance of our theoretical setting for Vietnam, we obtain some noteworthy findings that support our model propositions. First, there is a significant effect of entrepreneurial skills (proxied by education, industry experience, and managerial experience) in increasing the propensity of an occupational transition to habitual entrepreneurship. In addition, both serial and portfolio entrepreneurs are endowed with stronger human capital than their novice counterparts, and an increase in the quality of the new business increases the likelihood that it is run by a habitual entrepreneur, with a stronger incidence on portfolio entrepreneurs. Second, the interaction between entrepreneurial skills and business quality supports our theory that high skills and business quality are generally associated to a habitual entrepreneur. Third, novice entrepreneurs’ motivation to remain in their business is stronger if they have both high entrepreneurial skills and rich technical and managerial resources.

Our empirical analysis unveils other interesting results. While the businesses of both serial and portfolio entrepreneurs are endowed with significant technological resources, only portfolio entrepreneurs are more motivated to invest heavily in managerial resources for greater adaptability and to absorb knowledge spillovers in new industries/businesses. Investment capital does not seem to impact on the likelihood of habitual entrepreneurship. Land ownership and leveraging debts are favorable to business expansion activities of portfolio entrepreneurs only. Regarding survival, in general, firms run by habitual entrepreneurs have a longer duration than those run by novice ones. Technological quality is negatively associated with firm survival, which is consistent with many studies supporting the low survival chance of young innovative companies or new technology–based firms (e.g., Santarelli and Tran 2016). Although these capabilities enable entrepreneurs to be responsive to dynamic changes in the market and thus transform their entrepreneurial efforts into observable material outcomes, they are quite costly and challenging to develop and manage, especially for inexperienced novice entrepreneurs. However, managerial expertise from the firm management team does help entrepreneurs lengthen their survival duration.