Abstract

The number of individuals with student loan debt who do not earn their degrees is on the rise; nevertheless, there is little research that demonstrates their current circumstances and future aspirations. We address this knowledge gap by comparing the financial distresses and re-enrollment aspirations of student debt-holders who started college but did not earn a degree—those with non-degreed debt (NDD)—to (a) individuals who have a high school diploma and no student debt, (b) individuals with some college and no student debt, and (c) individuals with a college degree and no student debt, and (d) individuals with a college degree and student debt. Through these “downwards,” “sideways,” and “upwards” comparisons, we are able to provide a 360 degree view of the unique circumstances and outlooks faced by individuals with non-degreed debt. We find that individuals with NDD had greater odds of experiencing material and healthcare hardships, as well as financial difficulties. Individuals with NDD also had greater levels of financial anxiety and lower levels of financial well-being. Despite these challenges, individuals with NDD were often more optimistic about their future college enrollments and earnings. We discuss the implications of these findings with regards to financial aid policies, debt repayment policies, and college retention and re-enrollment efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Educational attainment and earnings in the U.S. are strongly linked (Angrist & Krueger, 1991; Card, 1999; Heckman, Humphries, & Veramendi, 2018; Hout, 2012). Workers with a Bachelor’s degree earn substantially more than workers without a bachelor’s degree (Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS], 2020b; Day & Newburger, 2002; Oreopoulos, & Petronijevic, 2013; Ost, Pan, & Webber, 2018), and individuals with a bachelor’s degree are less likely to be unemployed (BLS, 2020a). However, the earnings premium of a bachelor’s degree is threatened by rising higher education costs and student loan borrowing (Bricker & Thompson, 2016; Snyder, de Brey, & Dillow, 2019). Nearly two-thirds (62%) of college seniors who graduated in 2019 did so with student debt; these students owed an average of $28,950 in undergraduate student loans – an increase of 56% since 2004 (Institute for College Access and Success, 2020).

Despite the record amount of outstanding student debt in the U.S.—1.7 trillion dollars in 2020, the total amount of student debt may not be a problem in itself (Baum, 2017), as graduate students tend to have the highest rates of borrowing and subsequent earnings, as well as the lowest rates of default (Looney & Yannelis, 2015). However, it is important to note that due to the changing characteristics of undergraduate borrowers—now including larger shares of lower-income students—cumulative student loan default rates are on the rise (Scott-Clayton, 2018). In fact, nearly 30% of borrowers are estimated to eventually default (Looney & Yannelis, 2015) and 9% of federal student borrowers from the 2017 cohort were in default within just three years of entering repayment (The College Board, 2020). In addition to repayment difficulties, student debt is associated with lower levels of financial assets (e.g., Zhan, Xiang, & Elliott, 2016) and net worth (Fry, 2014), as well as reduced consumption rates (e.g., Bahadir & Gicheva, 2019) and greater incidences of material hardship (Despard et al., 2016).

As a result, student debt has entered the political mainstream as a key challenge to address, reflected in various proposals concerning income-driven repayments, loan forgiveness, and even free college. Nevertheless, borrowing and repayment behavior is not homogenous. Gross et al. (2009) reviewed 41 studies from 1978 to 2007 and found that different student characteristics and family backgrounds, college experiences, and institutional characteristics explain variation in default rates. More recent evidence indicates that high-balance borrowers, who are more likely to be graduate students, tend to have better employment and repayment outcomes than other borrowers (Looney & Yannelis, 2019). Conversely, default rates are especially high among borrowers who attended for-profit institutions and those with the lowest amounts owed (Baum, 2017; Board of Governors, 2020; Scott-Clayton, 2018).

Problems repaying student debt are particularly pronounced among borrowers who left college before earning their degrees. The proportion of non-completers who defaulted within two years of entering repayment was 24% in 2011–12 compared to 9% of graduates (Baum, 2017). Non-completers were also the most likely group to be behind in their loan payments – 40% of non-completers were behind compared to just 15% and 8% of those with an associate’s and bachelor’s degree, respectively (Board of Governors, 2020). Compared to graduates with student debt, non-completers are more likely to be unemployed, default on their loans, and have lower earnings compared to borrowers who finished their degrees (Board of Governors, 2020; Nguyen, 2012; Wei & Horn, 2013).

While the research on student debt and homeownership have had mixed findings (Houle & Berger, 2015; Mezza et al., 2019; Robb, Schreiber, & Heckman, 2020), Anderson (2015) showed that homeownership rates are lowest among non-completers with student debt – even lower than among those with no degree and no student debt. As there are numerous factors that go into decisions to start college, take on student debt, and leave before graduating—as well as whether to buy a home, these findings are not causal. Nevertheless, these findings paint a picture of the circumstances faced by debt-holding non-completers, which, ultimately, can help policy-makers and other stakeholders consider ways to improve these circumstances. However, little is known about a broader set of financial circumstances at the intersection of student debt and non-completion, particularly among lower-income individuals. Moreover, there is no research that demonstrates their aspirations for future earnings and re-enrollments. We address this knowledge gap by using a unique sample of lower-income tax filers and survey respondents to compare financial outcomes and future outlooks of non-completers with student debt – individuals with “non-degreed debt” (NDD) – to (a) individuals who have a high school diploma and no student debt, (b) individuals with some college and no student debt, (c) individuals with a college degree and no student debt, and (d) individuals with a college degree and student debt. As a result, we are able to pull apart the conditions associated with both college non-completion and student debt. Through these “downwards,” “sideways,” and “upwards” comparisons, we are able to provide a 360 degree view of the unique circumstances and outlooks faced by individuals with non-degreed debt.

When compared to all other groups, we find that individuals with NDD were associated with greater odds of material and healthcare hardships and financial difficulties. With the exception of individuals with a college degree and student dent, we find that individuals with NDD were associated with higher levels of financial anxiety, and lower levels of financial well-being when compared to all other groups. Yet NDD individuals were also associated with greater expectations of future earnings and college enrollment. These findings suggest that individuals with NDD are a uniquely disadvantaged yet optimistic population of borrowers. Our findings can help inform the policy debate surrounding student debt and financial aid by more deeply exploring the objective and subjective ramifications associated with student debt and non-completion. Additionally, our findings can inform college and university efforts aimed at supporting and re-engaging debt-holding non-completers.

Background

Student Debt and Financial Distress

Student debt represents an investment in future income and asset growth through the earnings premium often conveyed with a college degree. However, some research indicates a link between student debt and various indicators of financial distress. Using data from the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), Bricker and Thompson (2016) found that student debt was associated with making late bill payments and being denied credit; these results generally did not hold for other forms of debt. Using an instrumental variable approach to analyze multiple waves of SCF data, Gicheva and Thompson (2015) found that higher amounts of student loan debt were linked to credit constraints and increased likelihood of filing for bankruptcy. Among lower-income tax filing households, Despard et al. (2016) found that households with student debt were at greater risk for material hardship and financial difficulties compared to households without student debt. At the macro level, Bahadir and Gicheva (2019) found that higher levels of student debt-to-income ratios caused a reduction in the growth rate of aggregate, state-level consumption in the medium term.

Additional research indicates a negative relationship between student debt and subjective measures of financial well-being and general life satisfaction. Based on a systematic review, Pisaniello et al. (2019) found a significant association between student debt and self-reported stress, worry, and financial distress among medical students in several countries. Additionally, Archuleta, Dale, and Spann (2013) found that student loan debt was positively correlated with financial anxiety when controlling for other types of debt. Kim and Chatterjee (2019) also reported a negative association between student debt and life satisfaction after controlling for other forms of debt.

Presumably, higher amounts of student debt should to be associated with greater financial distress, yet the evidence is unclear. Akers (2014) found that financial hardship was more acute among households with lower student debt levels but did not increase for higher student debt levels. Among lower-income tax filing households with student debt, higher amounts of debt were not associated with increased risk of material hardship or financial difficulty (Despard et al., 2016). Similarly, borrowers with lower levels of debt (under $15,000) are more likely to be behind in their payments (21%) compared to those with debt of $15,000 or higher (14%) (Board of Governors, 2020). However, Zhang, Wilcox, & Cheema (2019) found that households with low and high student debt levels were significantly more likely to spend beyond their incomes than those with moderate debt levels. These inconsistent findings reflect Hillman’s (2014) observation that the relationship between debt amounts and default risk is non-linear.

Rather, borrowers’ ability to service their debt may be a better predictor of financial distress than loan amount. A borrower who defaults on their student loan presumably cannot afford their loan payments based on their income and need to cover other expenses such as housing, food, and other debt payments. Thus, the “crisis” of student debt is not necessarily about the amount of outstanding debt, but rather about many borrowers’ inability to afford repayments based on low earnings (Dynarski, 2016). For example, borrowers with the highest amounts of debt have better repayment outcomes than those with the lowest amounts due to better employment and earnings outcomes (Looney & Yannelis, 2019).

Unsurprisingly, borrowers’ post-college employment and income are key predictors of difficulties repaying student loans (Gross et al., 2009; Hillman, 2014; McMillion, 2004; Mueller & Yannelis, 2019; Price, 2004; Scott-Clayton, 2018; Witteveen & Attewell, 2019). Conversely, enrollment in Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plans – which limit debt payments to 10 to 15% of income by extending the loan term – are associated with lower default rates (1%) compared to standard loan repayment plans (14%) (Government Accountability Office [GAO], 2015). Additionally, other factors related to difficulty repaying student loans can include lower credit scores (Mezza & Sommer, 2016), net worth (Lee, Kim, & Hong, 2018), race (Chakrabarti, Nober, & van der Klaauw, 2020; Gross et al., 2009; Herr & Burt, 2005; Price, 2004; Scott-Clayton, 2018), and attendance at a for-profit institution (Belfield, 2013; Gross et al., 2009; Scott-Clayton, 2018; Witteveen & Attewell, 2019).

The role of non-completion

Numerous studies show a link between non-completion and poor financial outcomes, including debt burdens (Gladieux & Perna, 2005; Nguyen, 2012; Wei & Horn, 2013), homeownership rates (Anderson, 2015), credit constraints, late bill payments, and bankruptcies (Gicheva & Thompson; 2015). However, given that a fifth of all borrowers drop out of college (Gladieux & Perna, 2005), previous research has begun to uncover the links between non-completion and student loan defaults (Baum, 2017; Board of Governors, 2020; Herr & Burt, 2005; Hillman, 2014; Itzkowitz, 2018; McMillion, 2004; Nguyen, 2012; Wei & Horn, 2013; Woo, 2002). In fact, in their review of 41 studies on default, Gross et al. (2009) identify degree non-completion as the single largest predictor of student loan default. Given that non-completers who take out loans have to repay their debts without an earnings premium from a degree, this finding is unsurprising. Also unsurprising, the relationship between non-completion and financial problems for debt-holders appears to be bi-directional. Lower-income non-completers are disproportionately from lower-income families (Gladieux & Perna, 2005). Here, Terriquez and Gurantz (2015) found that students’ own financial circumstances, such as the ability cover tuition and secure housing, as well as their propensity to of offer financial assistance to family members, affected their decisions to drop out.

Additionally, it is important to note that borrowing factors can often turn into persistence factors. For example, among students eligible for Pell Grants and those whose aid package covers the cost of attendance, college persistence was found to be higher without loans than with loans (Herzog, 2018). Here, Gladieux and Perna (2005) depict lower-income students as in a “double bind” – often working while in school (another risk factor for non-completion) in order to avoid additional borrowing and the risks of being unable to afford future loan payments. Finally, Destin and Svoboda (2018) found that taking on greater amounts of student loans was associated with lower grades and likelihoods of graduation. In an experiment, the authors found that prompting participants to think about high college costs lowered cognitive functioning among those who expected their college degrees to result in future financial success.

Study purpose

The evidence reviewed reveals that the problems associated with student debt depends on borrowers’ ability to repay their loans relative to their income. Furthermore, as degree non-completion emerges as the single greatest factor predicting repayment, financial problems are not merely a consequence of non-completion among borrowers, but they are also a potential risk for non-completion. Nevertheless, these financial problems are not well understood, especially among lower-income borrowers and non-completers. Moreover, there is little research that explores the aspirations of those with NDD, which is especially troubling when considering that this group is uniquely situated to re-enroll. Thus, by better understanding the problems that those with NDD face, as well as the opportunities, such as re-enrollment aspirations, stakeholders in higher education can better support and re-engage these individuals. Accordingly, we use a sample of lower-income tax filers to answer the following research questions:

-

1.

Are borrowers who did not complete college associated with greater risks for objective and subjective measures of financial distress compared to non-borrowers who never attended college, non-borrowers who did not complete college, borrowers who earned a degree, and non-borrowers who earned a degree?

-

2.

Are borrowers who did not complete college associated with different earnings expectations and future enrollment aspirations compared to non-borrowers who never attended college, non-borrowers who did not complete college, borrowers who earned a degree, and non-borrowers who earned a degree?

By exploring the intersection of student debt and non-completion, our study extends the literature on student debt and financial outcomes in three ways. First, we focus on the population of lower-income borrowers. Existing research has paid relatively little attention to the issues of student debt and non-completion in the context of lower-income households, even though these households experience greater student debt burdens and loan repayment difficulties (Baum & O’Malley, 2003; Hillman, 2014; Looney & Yannelis, 2015), face greater liquidity constraints (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2020), may be more susceptible to over-borrowing and high-cost borrowing (Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013), and are at the greatest risk for non-completion. Additionally, a state shift from need-based to merit-based financial aid (Elliott & Friedline, 2013) and the declining purchasing power of Pell Grants (Protopsaltis & Parrott, 2017) has disproportionately affected lower-income and minority students.

Second, we go beyond loan repayment to examine a broader set of financial challenges that have not been examined in prior research. We use multiple measures of objective hardships and financial difficulties, while also incorporating indicators of subjective financial well-being, including financial anxiety and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s (CFPB, 2015) Financial Well-Being Scale, which was recently used by Korankye and Kalenkoski (2021) in the context of student debt. We also focus on opportunities for this population of borrowers, such as earnings expectations and re-enrollment aspirations that can provide stakeholders with a greater impetus for action.

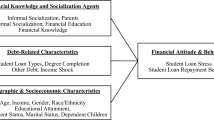

Finally, we concentrate on individuals with no degree and debt (NDD)—a group most studies on student debt overlook. This is a particularly vulnerable segment of student debt holders, as these individuals face the costs of student debt without the ability to fully capitalize on the benefits of higher education. For studies that do consider the NDD population, comparisons typically focus on one group, which limits the ability to pull apart the circumstances associated with both student debt and non-completion. Thus, we also make “downward” comparisons to those who never attended college and have no student debt, “sideways” comparisons to those with some college but no debt, as well as those with a college degree and debt, and “upwards” comparisons to those with a college degree and no debt. By providing a 360 degree view of the circumstances and outlooks associated with NDD, we are able to pull apart the conditions associated with both college non-completion and student debt, as well as descriptively approximate the counterfactual circumstance (e.g. the conditions that someone with NDD would be associated with if they had never attended college, taken on student debt, and withdrew before completing) (Fig. 1). This can offer unique insights that can help guide student loan and college re-enrollment policies and practices.

Data and methods

In this study, we are interested in examining how material and healthcare hardships, financial difficulties, financial anxiety and well-being, as well as future expectations related to work and education, differ for lower income individuals with non-degreed debt (NDD). Thus, we compare individuals who have NDD to (a) individuals who have a HS Diploma/GED (‘HSD’) without any student debt, (b) individuals with some college without student debt (‘Some College, No Debt’), and (c) individuals with a college degree with student debt (‘College Degree with Debt’), and individuals with a college degree without student debt (‘College Degree, No Debt’). Given our current sample and available measures, we cannot account for all the factors that can explain the decisions to pursue post-secondary education, take on student debt, and leave school before graduating. Nevertheless, we can strengthen our results by controlling for an array of key demographic and financial characteristics associated with the outcomes.

Data

Data for this study come primarily from the 2017 Household Financial Survey (HFS), which gathered detailed information on a variety of measures related to household finances, such as educational attainment, student debt, hardships, financial difficulties, financial well-being and anxiety, and future expectations of earnings and education. The HFS was administered to individuals who consented to participate in the survey following completion of their tax preparation and tax filing in Intuit’s TurboTax Freedom Edition (TTFE) in 2017.Footnote 1 As part of the Internal Revenue Service’s (IRS) Free File Alliance Program,Footnote 2 the TTFE tax-preparation and tax-filing software is free for low and moderate income (LMI) tax filers who meet certain income and/or military service criteria. In 2017, the qualifying criteria for using TTFE were: (a) claiming the Earned Income Tax Credit, (b) having an adjusted gross income (AGI) less than or equal to $32,000, or (c) being an active duty military serviceperson with an adjusted gross income less than or equal to $64,000Footnote 3. For the analysis, HFS data were merged with administrative tax records. By using administrative data, we were able to observe the precise values of household AGI and dependents in a household. As demonstrated by others research using the HFS (see Gallagher, Gopalan, & Grinstein-Weiss, 2019), the survey sample is similar, although not identical to the broader LMI population. By comparing the HFS to low-income households from the American Community Survey, Gallagher et al. (2019) found that the HFS tended to be younger, and have greater proportions of white respondents, unmarried respondents, and student respondents. Following other researchers using the HFS (2019), we believe that the demographic controls used in our study, such as age, race/ethnicity, gender, marital/partner status, dependents, adjusted gross income, student status, employment status, and educational attainment, should account for most of these differences.Footnote 4

Sample

In total, 23,834 individuals completed the HFS after they filed their tax returns. We removed individuals who were currently enrolled in school (n = 7,451) and individuals who had student loans that were not theirs (n = 712). Individuals were asked the following question about their educational attainment:

What is the highest level of education you have completed?

-

Some high school.

-

High school diploma or G.E.D.

-

Some college.

-

College degree.

-

Some graduate/professional school.

-

Graduate or professional degree.

.

While non-completion can occur across multiple education degree programs (e.g. Vocational and Associates’ programs, Bachelors’ programs, Graduate programs, etc.), we focus on undergraduate programs, as these are often the largest programs with the highest rates of non-completion (Wei & Horn, 2013). We therefore adopt a question used by the U.S. Census Bureau in the Current Population Survey’s Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) to better understand non-completion. Based on the above question, “college” encapsulates vocational and Associates programs (e.g. 2-year degrees), as well as Bachelor programs (e.g. 4-year degrees), while “some” signifies non-completion (i.e. no degree). We therefore removed individuals with less than a high school diploma or general equivalency (n = 461), as well as individuals with a higher than a bachelor’s degree (n = 2,682). Furthermore, we removed 100 individuals who had a high school diploma as their highest level of education and who had incurred student debt (these students likely paid for courses but did not earn credits for them). This left:

-

1,994 Low and Moderate Income (LMI) individuals who had high school diplomas or equivalent without student debt;

-

2,620 LMI individuals who completed some college (but did not graduate) without student debt;

-

1,465 LMI individuals who completed some college (but did not graduate) with student debt;

-

2,676 LMI individuals who had a college degree with student debt; and.

-

2,811 LMI individuals who had a college degree without student debt.

.

Finally, there was some listwise deletion in the final models that resulted in a small number of additional individuals being removed from the sample (less than 5% of our total sample).

Analytic Strategy

For our main results, we utilized logistic regression for binary outcomes and linear regression for continuous outcomes. In order to compare those with NDD to all other groups, NDD was set to the base category. Additionally, we use marginal estimates and accompanying plots to visualize the differences across all groups. Finally, post-estimation diagnostic checks were used to explore collinearity. All predictors had variance inflation factors (VIF) below 3, which signifies low levels of collinearity.

Measures

Dependent variables

We examined the association among NDD and outcomes related to material and healthcare hardships, financial difficulties, financial anxiety and well-being, and future expectations of earnings and college enrollment. Construction of the hardship variables was informed by similar items used in large panel studies, such as the Survey of Income and Program Participation, as well as the Fragile Families and Child Well-Being Study (see Despard et al., 2016). A dummy variable for experiencing a material hardship in the six months prior to tax filing was created for individuals that indicated their household could not afford to make a full rent or mortgage payment, skipped or made a late payment on a bill, or experienced food insecurity (1 = yes; 0 = no). A dummy variable for experiencing a healthcare hardship in the six months prior to tax filing was created for individuals that indicated their household could not afford to see a doctor or dentist for medical care or could not afford to fill a prescription (1 = yes; 0 = no). For financial difficulties, we created a dummy variable for whether individuals or someone in their household experienced a bank overdraft or had a credit card payment declined in the six months prior to tax filing (1 = yes; 0 = no).

While hardship and financial difficulty measures focused on objective circumstances, financial anxiety and well-being measures focused on individuals’ subjective financial experiences. The Financial Anxiety Scale (FAS) was adapted from the seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale, which was developed and validated by Shapiro and Burchell, 2012 (and later used by and Archuleta, Dale, and Spann, 2013). Based on a Likert scale—ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always)—the FAS asks participants how often: “They feel anxious about their financial situations”; “They experience difficulty sleeping due to their financial situations”; “They experience difficulty concentrating at work due to their financial situations”; “They feel irritable due to their financial situations”; “They experience difficulty controlling their worry about their financial situations”; “Their muscles feel tense due to worrying about their financial situation”; and “They feel fatigued due to worrying about their financial situations.”

The Financial Well-Being (FWB) scale considers financial security and freedom of choice both presently and in the future. We used an abbreviated scale (validated by the CFPB) that consists of the following five items (CFPB, 2015): “I am just getting by financially”; “I am concerned that the money I have or will save won’t last”; “Because of my money situation, I feel like I will never have things I want in life”; “My finances control my life”; and “I have money left over at the end of the month.” These statements are measured on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5: responses for the first three questions include “Completely, Very well, Somewhat, Very little, Not at all,” and response categories for the last two questions are “Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never.” The FWB scale takes into account whether individuals are above or below age 61, as FWB can be impacted by both age and the ability to draw on retirement benefits. This age standardization scoring technique is informed by item response theory (IRT) and recommended by the CFPB (CFPB, 2015).

Finally, in order to understand how NDD relates to future expectations, we considered whether or not an individual expected to earn more in the near future (1 = yes; 0 = no), as well as whether or not an individual planned to enroll in college in the near future (1 = yes; 0 = no). While previous research using this survey conceptualizes “near” as within the next year (see Jabbari, Roll, Bufe, and Chun, 2022), conceptions of time tend to systematically differ across the life span. Thus, we control for age (as discussed later), and use “near” as way for respondents to define their own timeframe. Here, asking about near future enrollment is meant to capture participants’ active set of intentions that reflect motivation and interest in college, such that having NDD may motivate one to complete an unfinished goal or recover sunk costs, or perhaps discourage one from pursuing what may feel like an unattainable goal. Similar to the research on college savings and “future selves” (see Elliott, Choi, Destin, & Kim, 2011), it is often the intention that is of primary concern and not necessarily when the intended behavior will occur.

Covariates

Covariates capture the following demographic information: age; gender (1 = male; 0 = female/other); race/ethnicity—whether individuals identified as White, Black, Asian, Other, or Hispanic; whether or not individuals had dependents (1 = yes; 0 = no); and whether or not individuals were married or lived with a partner (1 = yes; 0 = no). In addition to demographic information, covariates capture financial information as well, including; household’s adjusted gross income (AGI); employment status: not currently working (1), full-time employment (2), and part-time employment (3); liquid assets—including amounts reported in checking accounts, savings accounts, and cash; unsecured debt—including amounts reported on credit cards, payday loans, and negative balances in checking accounts; owning a home (1 = yes; 0 = no); owning a car (1 = yes; 0 = no); having health insurance (1 = yes; 0 = no); believing that they could come up with $2,000 if a financial emergency arose within the next month (1 = yes; 0 = no); having careful budgeting habits (1 = someone who budgets carefully is like me; 0 = someone who budgets carefully is not like me); and experiencing any of the following financial shocks in the previous six months (1 = yes; 0 = no): unexpected job loss, unexpected income reduction, unexpected major house or appliance repair, unexpected major vehicle repair, unexpected legal fees, unexpected medical expenses, unexpected natural disaster, unexpected criminal victimization, and unexpected major life change that affected individuals financially (e.g., birth, death, divorce, separation). Variables measuring dependents and household AGI were observed in the administrative tax data, whereas remaining the measures came from the survey data.

In order to censor extreme outliers, age, liquid assets, and unsecured debt variables were winsorized at the upper-bound 99th percentile. This resulted in 115 responses being winsorized for age, 94 responses being winsorized for unsecured debt, and 114 responses being winsorized for liquid assets. Finally, while liquid assets where transformed into quartiles, due to a disproportional amount of the sample that had no unsecured debt, this variable was transformed into a categorical variable consisting of four categories: (1) no unsecured debt: $0; (2) low unsecured debt: $1–800 ; (3) moderate unsecured debt: $801–3,500; and (4) high unsecured debt: $3,501 − 30,000. Notably, individuals with unsecured debt were equally distributed into the latter three categories.

Results

Sample description

Sample description is provided in Table 1 and broken down by education/debt categories in Table 2. The average age of participants in the sample was 38, and there was a nearly equal proportion of male and female/other participants (46% male; 54% female/other). The majority of participants were Non-Hispanic White (75%), employed full-time (55%), owned a car (74%), had health insurance (88%), would be able to come up with $2,000 in case of an emergency (52%), had careful budgeting habits (79%), experienced a shock in the six months prior to tax filing (62%), and had roughly $17,406 a year in a household AGI. A smaller proportion of participants were married or lived with a partner (33%), had dependents (23%), and owned a house (28%). Additionally, the average amount of liquid assets for individuals in the sample ($4,169) was larger than the average amount of unsecured debt ($2,657). Finally, when considering the outcomes under study, experiencing material hardships (54%) and expecting to earn more in the future (52%) were more common in this sample; healthcare hardships (47%), financial difficulties (31%), and planning to attend college in the future (28%) were less common.

When breaking down our sample by education/debt category, interesting trends emerged relating to those with NDD. For example, those with NDD were younger than those with a HSD, those with some college and no debt, and those with a college degree and no debt; at the same time, those with NDD were slightly older than those with a college degree and debt. Those with NDD had the lowest rates of non-Hispanic White and Asian individuals and the highest rates of Black and Other individuals; those with NDD had lower rates of Hispanic individuals when compared to those with a HSD and those with some college and no debt, but higher rates of Hispanic individuals when compared to those with college degrees and no debt. Those with NDD had the highest rates of being married/having a partner, as well as having a dependent. With the exception of those with a college degree and debt, those with NDD had the highest rates of full-time employment and the lowest rates of unemployment. With the exception of those with a college degree and debt, those with NDD also had the highest levels of AGI. Those with NDD had the lowest rates of home and car ownership; with the exception of those with a HSD, those with NDD had the lowest rates of health insurance. Those with NDD had the lowest levels of liquidity and—with the exception of those with HSDs—the lowest levels of unsecured debt. Those with NDD had the lowest rates of emergency savings and good budgeting habits; at the same time, those with NDD had the highest rates of experiencing shocks, material hardships, healthcare hardships, and financial difficulties. Those with NDD had the highest levels of financial anxiety and the lowest levels of financial well-being. Finally, those with NDD had the highest rates of college enrollment plans and—with the exception of those with a college degree and debt—the highest rates of increased earnings expectations.

Non-degreed debt, material and Healthcare Hardships, and Financial Difficulties

Table 3 examines the association between NDD and Material (Model 1) and Healthcare Hardships (Model 2), as well as Financial Difficulties (Model 3). Across all outcomes, each comparison group was significantly associated with decreased odds of experiencing hardships and difficulties. Relative to individuals with NDD, those with HSDs were significantly associated with 58% lowered odds of material hardships, 40% lowered odds of healthcare hardships, and 52% lowered odds of financial difficulties; those with some college and no debt were associated with 41% lowered odds of material hardships, 22% lowered odds of healthcare hardships, and 30% lowered odds of financial difficulties; those with a college degree and debt were associated with 38% lowered odds of material hardships, 28% lowered odds of healthcare hardships, and 16% lowered odds of financial difficulties; and those with a college degree and no debt were associated with 56% lowered odds of material hardships, 35% lowered odds of healthcare hardships, and 37% lowered odds of financial difficulties.

In addition to NDD comparisons, when considering the marginal plot of material hardships (Fig. 2), it also becomes clear that those with some college and no debt, as well as those with a college degree with debt had greater probabilities of material hardships than both those with a HSD and those with a college degree and no debt. When considering the marginal plot of health hardships (Fig. 3), it also becomes clear that both those with some college and no debt had greater probabilities of material hardships than both those with an HSD and those with a college degree and no debt. For financial difficulties (Fig. 4), those with a college degree and debt had a greater probability of financial difficulties than all other groups, and those with some college and no debt had a greater probability of financial difficulties than those with a HSD.

As expected, both demographic and financial characteristics were also associated with hardships and difficulties. Across all outcomes, liquid assets and emergency savings were negatively associated with hardships and difficulties, while unsecured debt and experiencing shocks were positively associated with hardships and difficulties. In addition, for materials hardships, being categorized Other or Hispanic and having dependents were associated with increased odds for material hardships, while identifying as Male, increased AGI, owning a home, and having health insurance were associated with decreased odds of material hardships. Additionally, for healthcare hardships, increased age, being married/having a partner, and having careful budgeting habits were associated with increased odds for healthcare hardships, while identifying as Male, being Black, owning a home, and having health insurance were associated with decreased odds of healthcare hardships. Finally, for financial difficulties, being Black, being married/having a partner, and having dependents were associated with increased odds of financial difficulties, while increased age and having careful budgeting habits were associated with decreased odds of financial difficulties.

Non-degreed debt and financial anxiety and well-being

Table 4 examines the association between NDD and financial well-being (Model 4) and financial anxiety (Model 5). With the exception of those with a college degree and debt, each comparison group was significantly associated with increases in financial well-being (FWB) and decreases in financial anxiety (FA). Relative to individuals with NDD, those with HSDs were significantly associated with 2.273 point increase in FWB and a 2.107 point decrease in FA; those with some college and no debt were associated with 1.727 point increase in FWB and a 1.549 point decrease in FA; and those with a college degree and no debt were associated with 1.787 point increase in FWB and a 1.603 point decrease in FA.

In addition to NDD comparisons, when considering the marginal plot of FWB (Fig. 5), it also becomes clear that those with some college and debt had lower predicted means of FWB than those of all other groups (aside from those with NDD). Similarly, those with some college and debt had higher predicted means of FA than those of all other groups (aside from those with NDD).

As expected, both demographic and financial characteristics were also associated with financial well-being and anxiety—often depicting inverse relationships. Identifying as male, being Black or Hispanic, being married/having a partner, owning a home or a car, having health insurance, having liquid assets, and having emergency savings were associated with an increase in FWB and a decrease in FA, while having dependents, having unsecured debt, and experiencing shocks were associated with a decrease in FWB and an increase in FA. Increases in age were associated with a decrease in both FWB and FA. Additionally, being categorized as Other and having careful budgeting habits were associated with an increase in FWB, while full- and part-time employment, as well as increases in AGI, were associated with decreases in FA.

Non-degreed debt and future expectations

Table 5 examines the association between NDD and future earnings expectations (Model 6) and college enrollment plans (Model 7). Relative to individuals with NDD, those with HSDs were significantly associated with 44% lowered odds of increased earnings expectations, while those with some college and no debt were associated with 17% lowered odds of increased earnings expectations; alternatively those with a college degree and debt were associated with 41% greater odds of increased earnings expectations, while those with a college degree and no debt were associated with 18% greater odds of increased earnings expectations. For college enrollment plans, those with HSDs were significantly associated with 62% lowered odds of future enrollment plans; those with some college and no debt were associated with 27% lowered odds of future enrollment plans; those with a college degree and debt were associated with 48% lowered odds of future enrollment plans; and those with a college degree and no debt were associated with 49% lowered odds of future enrollment plans.

In addition to NDD comparisons, when considering the marginal plot of earnings expectations (Fig. 7), those with a college degree and no debt had higher probabilities of increased earnings expectations than all other groups, followed by those with a college degree and no debt, as well as those with some college and no debt. For college enrollment plans (Fig. 8), those with a some college and no debt had a greater probability of future college enrollment than all other groups—except NDD, while those with a college degree and debt, as well as those with a college degree and no debt, had higher probabilities of future college enrollment than those with a HSD.

As expected, both demographic and financial characteristics were also associated with earnings expectations and enrollment plans. Across both outcomes, being Black, Other, and Hispanic, having high levels of unsecured debt, having careful budgeting habits, and experiencing shocks were associated with greater odds of increased earnings expectations and college enrollment plans, while increases in age and owing a home were associated with lowered odds of increased earnings expectations and college enrollment plans. Additionally, identifying as male, having moderate levels of unsecured debt, and having emergency savings were associated with greater odds of increased earnings expectations, while full-time employment, increased earnings, and having health insurance were associated with lowered odds of increased earnings expectations. Finally, identifying as Asian was associated with greater odds of future enrollment plans, while being married/having a partner was associated with lowered odds of future enrollment plans.

However, when we add future enrollment plans as a predictor of earnings expectations (Model 8), having some college and no debt is no longer significantly associated with a lowered odds of increased earnings expectations. In addition to future enrollment plans, which was significantly associated with increased earnings expectations, we also noticed some changes in other model covariates. Specifically, higher levels of liquid assets (i.e. 3rd and 4th quintiles) were now significantly associated with lowered odds of increased earnings expectations, while being categorized as Other and experiencing shocks were no longer significantly associated with increased earnings expectations. Finally, it is important to note that the previous patterns in the marginal plot for increased earnings expectations remained similar when controlling for college enrollment plans (Fig. 9).

Student debt levels and Institution types

We also consider the relationships between the amount of debt held and each respective outcome among non-completers. In doing so, the sample was limited to individuals in LMI households with NDD (n = 1,437), and the amount of student debt was broken down into quartiles (first quartile: <$5,200; second quartile: $5,200-$12,499; third quartile: $12,500-$28,999; fourth quartile: $29,000+). For the most part, our findings (not shown) suggest that the actual amount of student debt is often less important in predicting associations with financial circumstances and experiences among LMI non-completers. In fact, the only significant relationship occurred with financial anxiety in which the highest quartile of student debt was associated with a 1.825 point increase in financial anxiety. Here, large amounts of student debt may have larger subjective, rather than objective effects. This finding is partly supported by previous research on total student debt burdens and financial anxiety (see Archuleta, Dale, & Spann, 2013).

In addition, we considered whether the type of institution had any impact on the outcomes among debt-holders (not shown), but similarly, there was only one significant relationship: when compared to those that attended a public university, those that attended a private for-profit university were less likely (OR = 0.69*) to have future college enrollment plans—perhaps because they had a negative experience at their previous institution.

Discussion

Despite the rising costs of higher education and a concomitant increase in the average amount of student debt, college often remains a worthwhile investment for students who graduate with a degree. Yet, less is known about the growing number of students who take on student debt, but do not graduate. In this study, we tell an important part of their story. From a sample of lower income tax filers, we examine the financial circumstances associated with NDD when compared to (a) individuals who have a HS Diploma/GED (‘HSD’) without any student debt, (b) individuals with some college without student debt (‘Some College, No Debt’), (c) individuals with a college degree with student debt (‘College Degree with Debt’), and (d) individuals with a college degree without student debt (‘College Degree, No Debt’). There are numerous factors (e.g. personal experiences, individual traits, and financial circumstances and resources, etc.) across the various decision points in which individuals pursue post-secondary education, take on student debt, and leave school before graduating. Ultimately, these factors may relate to an individual’s current financial conditions. While we cannot account for all of these factors, and thus cannot demonstrate causal relationships, our comprehensive descriptive approach allows us to better understand the associations of both debt and non-completion with an array of objective and subjective financial measures, as well as future expectations and aspirations.

In doing so, we find that the group with NDD was worse off financially—both in objective (e.g. hardships) and subjective (e.g. well-being) measures—when compared to almost all other groups. Specifically, we find that those with NDD were more likely to experience material hardships, healthcare hardships, and financial difficulties than those with HSDs, those with some college and no debt, and those college degrees—both with and without debt. When considering the marginal probabilities of these objective measures, while each facet on its own—non-completion and debt—often appeared to have unique disadvantages, it was the intersection of debt and non-completion that appeared to place individuals at a unique disadvantage. Here, the negative outcomes associated with NDD are not merely a product of college non-completion nor student debt in isolation. For example, if there was only a college non-completion problem, then we would likely not see any discernable differences across those with NDD and those with some college with no debt; likewise, if there was only a student debt problem, then we would likely not see any discernable differences across those with NDD and those who had a bachelors’ degree with debt. Thus, it is the convergence of college non-completion and student debt that are associated with the largest threats to well-being. Here, these findings suggest that those with NDD may experience a “double jeopardy” in their financial lives—these individuals miss an opportunity to “cash in” on the earnings premium afforded by a college degree and yet they are simultaneously saddled with unproductive debt that they must repay with these non-premium earnings.

However, there were some subtle differences when considering subjective conditions. While those with NDD were associated with higher levels of financial anxiety and lower levels of financial well-being than those with HSDs, those with some college and no debt, and those with college degrees without debt—these relationships were not significant when compared to those with a college degree and debt. This is confirmed in the marginal estimates of FWB and financial anxiety. Thus, while the intersection of debt and non-completion together appear to be motivating factors for objective measures of financial conditions, debt alone appears to be the motivating factor for subjective measures of financial conditions.

Nevertheless, while these associations suggest that it may be better to not attend college at all rather than to take on debt and not finish, given the growing earnings premium on college degrees, neither option is ideal. Furthermore, given that those with NDD were associated with greater odds of expecting to earn more in the future and return to school than those with a HSD and those with some college and no debt, our findings suggest that those with NDD may be particularly optimistic. Indeed, when we add future enrollment plans and find that those with some college and no debt are no longer associated with increased earning expectations, we can infer that the desire to finish what they started is the driving force of future optimism for non-completers. These individuals have already invested a large amount of resources in their post-secondary endeavors, and without returning to college to complete their degree, they may continue to face hardships in the repayment process that will ultimately impact their well-being. Thus, when considering the optimism of individuals with NDD—in terms of returning to school and eventually earning more—this group may be particularly receptive to interventions.

With all three objective outcomes, the greatest differences were found between those with NDD and those with a HSD, often followed closely by those with a college degree and no debt, suggesting that both non-completion and debt play an important role in hardships and difficulties. For subjective outcomes, the greatest differences were found between those with NDD and those with a HSD; however the differences were often quite similar between those with NDD and those with some college and no debt and between those with NDD and those with a college degree and no debt. This suggests that subjective conditions may have less to do with non-completion. While it is somewhat surprising to find that the largest differences were often between NDD and those with a HSD, it is important to note that—particularly in a lower-income sample—those with a HSD may have more stability in their financial lives than those with some college or a college degree may have. The fact that those with HSD’s were one of the oldest groups and one of the groups with the lowest levels of shocks supports this proposition. Those with a HSD were also least likely to expect to earn more, which may also suggest a level of stability.

Additionally, it was interesting to see that for increased earnings expectations the difference between those with NDD and those with a college degree and debt was larger than the difference between those with NDD and those with a college degree and no debt debt. Here, those with debt may be more likely to seek out opportunities to maximize their earnings in an effort to pay off their student debt. It was unsurprising to see that for college enrollment plans the differences between those with NDD and those with some college and no debt were smaller than the differences between those with NDD and other groups, as we would assume those with some college would be more likely to want to finish what they started. Nevertheless, it was somewhat surprising to see that the differences between those with NDD and those with a college degree with debt were fairly similar to the differences between those with NDD and those with a college degree and no debt. Here, it appears that once a degree is earned, debt may play a smaller role in returning to school.

Finally, it is important to note that these findings do not include graduate students—a group of students with higher earnings than other college graduates. Given these trends, we might assume even larger differences in the outcomes of those with NDD when compared to graduate students.

Implications

Persisting in College

Our findings underscore the importance of persistence among students who use student loans to help finance their education. While part-time or flexible class schedules should be considered as a potential policy remedy, as they have been found to help low-income and non-traditional students balance family and work responsibilities (see Elliott, 2002), efforts should also focus on re-enrollment. Of the nearly four million students with some college but no degree who re-enrolled within a five period, 46% discontinued their studies a second time (Shapiro et al., 2019). Taking this into account, re-enrollment efforts should be prompt, as degree completion rates tend to decline with increased “stop out” durations; in-fact, students who re-enrolled within three years had a much greater likelihood of degree completion when compared to students who re-enrolled in four to five years (Shapiro et al., 2019). As institutional ties can be severed when students drop out, colleges and universities might consider keeping students in a provisional or “holding” enrollment status, while maintaining regular communication about re-enrollment options and supports. Moreover, as only 38% of re-enrollees returned to the same institution (Shapiro et al., 2019), less restrictive policies concerning credit transfers may decrease barriers to re-enrollment (Chase, 2010). As many lower income students start out in a community college with the goal of transferring to and earning a degree from a four-year institution, smoothing the process of credit transfer from community colleges to four-year colleges and universities may also be critical in the success of non-completers (Monaghan & Attewell, 2015). Furthermore, as non-completers are more likely to re-enroll at public versus private institutions (National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, 2019), states may want to consider a larger role in re-enrollment efforts.

Furthermore, policy makers may consider ways colleges and universities could be incentivized to increase graduation rates. In many cases, the only risk to colleges and universities for borrowers who leave school before completing their degree is reputational. In this regard, greater transparency might be a necessary first step. For example, policies like the “College Transparency Act,” which was introduced in the senate in 2019 to make information on college graduation and student loan debt readily available to prospective students, should be considered. Of course, as noted by Baker, Cellini, Scott-Clayton, & Turner (2021), information alone will likely not be enough to improve outcomes for all students, and disclosures don’t necessarily cause institutions to improve, but rather “revise” the information that they are disclosing.

Given the economic risks borrowers shoulder when they do not finish their degrees, risk-sharing proposals should also be considered (see Chou, Looney & Watson, 2017; Webber, 2017) as a way to decrease defaults. Financial incentives should be considered as well. For example, the Obama Administration proposed a College Opportunity and Graduation Bonus program to reward colleges that graduate Pell students. These efforts may be especially important for for-profit institutions, where a disproportionate share of the NDD population comes from and whose NDD population has an unemployment rate that is 10% points higher than the total NDD population (Nguyen, 2012).

Financing College

Unsurprisingly, persisting in college and financing college are intimately related. Recently, Britt and her colleagues (2017) found that the stress associated with taking on student loans was negatively associated with persistence, while Stinebrickner and Stinebrickner (2008) found that financial insecurity and material hardship explained why students from lower income households dropped out of college. Nevertheless, given the current costs of college, avoiding student loans altogether can make it impossible for some students to afford college and force other lower income individuals to work longer hours while attending college that can eventually lead to non-completion (see Gladieux & Perna, 2005). Thus, when considering the role of financing education, efforts that can reduce the cost of attending college while not burdening students with additional debt should be pursued.

In this regard, recent research has demonstrated that increases in state grant-based aid can improve college completion (see Goldrick-Rab et al., 2016; Castleman & Long, 2016). Loan repayment programs (see Gershenfeld et al., 2019) and Pell grants (Alon, 2011; Denning, Marx, & Turner, 2019) have demonstrated similar findings. Here, it is important to note that while costs of attending college have risen sharply in recent years, the proportion of attendance costs covered by Pell Grants had slipped by 13% points over a 15 year period and was at a historic low of 29% in 2016 (Protopsaltis & Parrott, 2017). Thus, future research should explore the extent to which increasing the size of Pell Grants could both boost persistence and mitigate economic risks among students unable to finish their degrees.

Repaying loans

Furthermore, our findings convey important implications around student loan repayment. Among borrowers with NDD who plan to re-enroll, the deferment period could extend beyond six months without accrued interest if a re-enrollment plan was put in place. For borrowers with NDD who do not plan to re-enroll and fail to attend loan exit counseling, colleges and universities could still conduct outreach to help these students understand their repayment options, including income-driven repayment (IDR) plans, forbearance, and loan discharge. Of course, students with NDD may be particularly hard to reach, and many colleges may not have the capacity to conduct in-depth outreach. Here, colleges may consider “low-touch” technology interventions to maintain or initiate contact (see Mann-Levesque, 2018).

While some have noted the efficiency and effectiveness of universal debt cancellation (Calhoun & Harrington, 2020), stakeholders and policymaker may want to consider debt relief that focuses on NDD populations, especially those from lower incomes. For example, Gershenfeld, Zhan, and Hood (2019) found that undergraduate students from lower-income families who received loan replacement grants were more than twice as likely to graduate within five years relative to a comparison group of similar students. Moreover, as we did not find a relationship between the amount of debt and the outcomes under study (with the exception of financial anxiety), even relatively small amounts of debt relief (e.g. $10,000) may go a long way for those with NDD.

Considering race

Finally, when considering recent research (Ciocca-Eller & DiPrete, 2018) demonstrating that lower socioeconomic resources were significantly associated with—among other factors—the Black-White degree completion gap, it is unsurprising that there was a larger percentage of Black individuals with NDD when compared to all other groups. Thus, as NDD appears to be inequitably distributed across dimensions race, future efforts should prioritize students of color in college completion and student debt relief efforts.

Limitations and Strengths

While our control variables—derived from administrative tax data—can enhance our findings, we could not account for all the factors that can explain decisions to pursue post-secondary education, take on student debt, and leave school before graduating, nor the timing of these events relative to survey completion. Indeed, Ciocca-Eller and DiPrete (2018) and others, such as Mayhew and his colleagues (2016), have pointed to the importance of academic preparation and performance in predicting college persistence. Thus, in order to limit omitted variable bias and avoid issues of reverse causality and simultaneity, it is essential for future research to account for factors that influence decisions to pursue post-secondary education, take on student debt, and leave school before graduating—most of which require longitudinal data. In addition, longitudinal data would help researchers understand how the timing of enrollment, withdrawal, and graduation—with respect to age and the time-from-key events—are associated with current financial conditions, while also helping researchers understand individuals’ debt payment patterns, earnings trajectories, college re-enrollment plans.

It is also important to consider data accuracy and precision with respect to limitations. With recent research suggesting that college students can be poor reporters of sensitive information (Rosen, Porter, & Rogers, 2017), future studies in this area should consider leveraging administrative records to avoid the potential of inaccurate responses. Additionally, given the breadth of our “some college” measure and the potential for measurement error often associated with broad categories, future studies should also consider the various types of educational attainment in order to further differentiate “some college” from non-completion across vocational, Associate’s and Bachelor’s degree programs, as well as other certificate and training programs (see, for example, Strada Education Network, 2019).

Furthermore, future studies should also explore data that goes beyond lower-income individuals. While a lower-income sample allows us to focus on more vulnerable populations, it also limits the generalizability of our findings. Moreover, instead of using robustness checks to determine generalizability to a particular population (e.g. LMI), future studies should employ sampling strategies that result in a representative sample of an intended population.

Thus, as our study is prone to unobservable variable bias and limited in its ability to generalize to the entire population, future studies in this area can increase both internal and external validity by leveraging comprehensive sources of administrative and longitudinal data. Doing so will allow for a more nuanced understanding of persistence, as well as a more comprehensive understanding of differences across borrowers and non-borrowers over time. As using administrative and longitudinal data can help policymakers and practitioners better understand the causes of NDD, it can also point to better-informed solutions.

At the same time, there is much value in our descriptive study that capitalizes on a large data set consisting of both administrative tax data and a comprehensive survey. Advancing previous research, we present the first study that provides a comprehensive view of those with NDD—making downward, sideways, and upward comparisons. In doing so, we demonstrate that there is both a college non-completion problem and a student debt problem—and most importantly—that these problems and their potential solutions are fundamentally related. By leveraging administrative tax data, we are also able to control for a variety of key variables related to the outcomes under study—outcomes that capture recent objective measures (hardships), longer-term subjective dispositions (FWB), and future expectations and aspirations (earnings and enrollment). Regardless of the possible mechanisms at play, we demonstrate that at the convergence of non-completion and student debt consists of a set of individuals in a particularly precarious situation that deserves the attention of stakeholders and policy-makers in higher education.

Conclusions

College is more expensive than ever, but the most expensive college experiences are the ones that do not lead to a degree. Often lacking the earnings premiums afforded by a college degree, students with NDD may be unable to pay down their growing student debts. Thus, it is unsurprising that students who take out college loans but do not graduate are three times more likely to default on these loans than borrowers who complete college (United States Department of Education [DOE], 2015). Furthermore, when considering that the proportion of individuals taking on student debt and the proportion of individuals that do not complete college is on the rise, it is unsurprising that default rates are also on the rise. Every year a million people default on their student loan for the first time, while 33% of students pursuing bachelor’s degrees fail to graduate in six years (Student Achievement Measure, 2022). As rising default rates and ballooning student debt levels can impact us all, it is not only those with NDD that may be negatively impacted by “having nothing to show for it”; soon, we may all pay the price for it.

Notes

The data were obtained through the Refund to Savings (R2S) initiative, which is a continuing partnership between Washington University in St. Louis and Intuit, Inc.

Additional analyses were performed (not shown) that included military status to ensure robustness of findings. The estimates from this alternative specification were qualitatively similar to the estimates presented in this paper in magnitude, direction, and statistical significance.

Additional analyses were performed (not shown) that included constructed American Community Survey (ACS) weights to ensure robustness of findings. The estimates from this alternative specification were qualitatively similar to the estimates presented in this paper in magnitude, direction, and statistical significance. Code for analytical models, as well as ACS weight construction and application in robustness checks are available upon request.

References

Akers, B. (2014). How Much is Too Much? Evidence on Financial Well-Being and Student Loan Debt. Center on Higher Education Reform, American Enterprise Institute

Alon, S. (2011). Who benefits most from financial aid? The heterogeneous effect of need-based grants on students’ college persistence. Social Science Quarterly, 92(3), 807–829. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2011.00793.x

Anderson, J. (2015, September 16). Yes, first-time buyer demand is weak. But stop blaming student debt. Zillow. https://www.zillow.com/research/student-debt-homeownership-10563/

Angrist, J. D., & Krueger, A. B. (1991). Does Compulsory School Attendance Affect Schooling and Earnings? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), 979–1014. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937954

Archuleta, K. L., Dale, A., & Spann, S. M. (2013). College students and financial distress: Exploring debt, financial satisfaction, and financial anxiety. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 24(2), 50–62

Bahadir, B., & Gicheva, D. (2019). The Effect of Student Debt on Consumption: A State-Level Analysis

Baum, S. (2017). Student debt: Rhetoric and reality. Forum for Social Economics (46 vol., pp. 206–220). Routledge. 2

Baum, S., & O’Malley, M. (2003). College on Credit: How Borrowers Perceive Their Education Debt. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 33(3), 7–19

Belfield, C. R. (2013). Student loans and repayment rates: The role of for-profit colleges. Research in Higher Education, 54, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-012-9268-1

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2020). Report on the economic well-being of U.S. households in 2019, featuring supplemental data from April 2020. Author. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2019-report-economic-well-being-us-households-202005.pdf

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2020). Student Loans Owned and Securitized, Outstanding [SLOAS]. Retrieved January 26, 2020, from https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SLOAS

Bricker, J., & Thompson, J. (2016). Does Education Loan Debt Influence Household Financial Distress? an Assessment Using the 2007–2009 Survey of Consumer Finances Panel. Contemporary Economic Policy, 34(4), 660–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12164

Britt, S. L., Ammerman, D. A., Barrett, S. F., & Jones, S. (2017). Student loans, financial stress, and college student retention. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 47(1), 25–37. https://ir.library.louisville.edu/jsfa/vol47/iss1/3

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020a). Unemployment rates for persons 25 years and older by educational attainment. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/charts/employment-situation/unemployment-rates-for-persons-25-years-and-older-by-educational-attainment.htm

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020b). Usual Weekly Earnings of Wge and Salary Workers, Fourth Quarter. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/wkyeng.pdf

Calhoun, M., & Harrington, A. (2020). The next COVID-19 relief bill must include student debt cancellation. Brookings Report. Retrieved from: https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-next-covid-19-relief-bill-must-include-student-debt-cancellation/

Card, D. (1999). The causal effect of education on earnings. In Handbook of Labor Economics (Vol. 3, pp. 1801–1863). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1573-4463(99)03011-4

Castleman, B. L., & Long, B. T. (2016). Looking beyond enrollment: The causal effect of need-based grants on college access, persistence, and graduation. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(4), 1023–1073. https://doi.org/10.1086/686643

Chakrabarti, R., Nober, W., & van der Klaauw, W. (2020). Measuring racial disparities in higher education and student debt outcomes (Liberty Street Economics). Federal Reserve Bank of New York. https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/07/measuring-racial-disparities-in-higher-education-and-student-debt-outcomes.html

Chase, M. M. (2010). Student transfer policies and practices in the United States and Europe: Mobility without loss of credit. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 47(1), 99–119. https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.6022

Chou, T., Looney, A., & Watson, T. (2017).A Risk-Sharing Proposal for Student Loans

College Board (2020). Trends in college pricing and student aid 2020. https://research.collegeboard.org/pdf/trends-college-pricing-student-aid-2020.pdf

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2015). Measuring financial well-being. Washington, DC: Author. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201512_cfpb_financial-well-being-user-guide-scale.pdf

Day, J. C., & Newburger, E. C. (2002). The Big Payoff: Educational Attainment and Synthetic Estimates of Work-Life Earnings. In Current Population Reports

Denning, J. T., Marx, B. M., & Turner, L. J. (2019). ProPelled: The effects of grants on graduation, earnings, and welfare. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 11(3), 193–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20180100

Despard, M. R., Perantie, D., Taylor, S., Grinstein-Weiss, M., Friedline, T., & Raghavan, R. (2016). Student debt and hardship: Evidence from a large sample of low- and moderate-income households. Children and Youth Services Review, 70, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.001

Destin, M., & Svoboda, R. C. (2018). Costs on the mind: The influence of the financial burden of college on academic performance and cognitive functioning. Research in Higher Education, 59, 302–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9469-8

Dynarski, S. (2016). The trouble with student loans? Low earnings, not high debt (Report). Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-trouble-with-student-loans-low-earnings-not-high-debt/

lliott, K. M. (2002). Key determinants of student satisfaction. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 4(3), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.2190%2FB2V7-R91M-6WXR-KCCR

Elliott, W., & Friedline, T. (2013). “You pay your share, we’ll pay our share”: The college cost burden and the role of race, income, and college assets. Economics of Education Review, 33, 134–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2012.10.001

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (2020). Student loans owned and securitized, outstanding [SLOAS]. Retrieved December 10, 2020 from https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SLOAS

Fry, R. (2014). Young adults, student debt, and economic well-being. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/05/14/young-adults-student-debt-and-economic-well-being/

Gershenfeld, S., Zhan, M., & Hood, D. W. (2019). The impact of a promise: A loan replacement grant, low-income students, and college graduation. The Review of Higher Education, 42(3), 1073–1100

Gicheva, D., & Thompson, J. (2015). The effects of student loans on long-term household financial stability. In B. Hershbein & K. M. Hollenbeck (Eds.), Student Loans and the Dynamics of Debt (pp. 287–316). https://doi.org/10.17848/9780880994873.ch9

Gladieux, L., & Perna, L. (2005). Borrowers who drop out: A neglected aspect of the college student loan trend. San Jose, CA: The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED508094.pdf

Goldrick-Rab, S., Kelchen, R., Harris, D. N., & Benson, J. (2016). Reducing income inequality in educational attainment: Experimental evidence on the impact of financial aid on college completion. American Journal of Sociology, 121(6), 1762–1817

Gershenfeld, S., Zhan, M., & Hood, D. W. (2019). The impact of a promise: A loan replacement grant, low-income students, and college graduation. The Review of Higher Education, 42(3), 1073–1100. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2019.0030

Government Accountability Office (2015). Federal student loans: Education can do more to help ensure borrowers are aware of repayment and forgiveness options (GAO-15-663). Author. https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/672136.pdf

Gross, J. P., Cekic, O., Hossler, D., & Hillman, N. (2009). What Matters in Student Loan Default: A Review of the Research Literature. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 39(1), 19–29

Heckman, J. J., Humphries, J. E., & Veramendi, G. (2018). Returns to education: The causal effects of education on earnings, health, and smoking. Journal of Political Economy, 126, S197–S246. https://doi.org/10.1086/698760

Herzog, S. (2018). Financial aid and college persistence: Do student loans help or hurt? Research in Higher Education, 59, 273–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9471-1

Herr, E., & Burt, L. (2005). Predicting Student Loan Default for the University of Texas at Austin. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 35(2), 27–49

Hillman, N. W. (2014). College on credit: A multilevel analysis of student loan default. The Review of Higher Education, 37(2), 169–195

Houle, J. N., & Berger, L. (2015). Is student loan debt discouraging homeownership among young adults? Social Service Review, 89(4), 589–621. https://doi.org/10.1086/684587

Institute for College Access and Success (2020). Student debt and the class of 2019. https://ticas.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/classof2019.pdf

Itzkowitz, M. (2018). Want more students to pay down their loans? Help them graduate. Third Way. https://www.thirdway.org/report/want-more-students-to-pay-down-their-loans-help-them-graduate

Kim, J., & Chatterjee, S. (2019). Student Loans, Health, and Life Satisfaction of US Households: Evidence from a Panel Study. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40(1), 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-018-9594-3

Lee, J. M., Kim, K. T., & Hong, E. J. (2018). Exploring financial burdens of student loan holders in the United States. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 46(4), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcsr.12261

Looney, A., & Yannelis, C. (2015). A crisis in student loans? How changes in the characterisics of borrowers and in the institutions they attended contributed to rising loan defaults (Brookings Papers on Economic Activity). Brookings Instituion Press. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/616850/summary

Looney, A., & Yannelis, C. (2019). How useful are default rates? Borrowers with large balances and student loan repayment. Economics of Education Review, 71, 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.10.004

Mayhew, M. J., Rockenbach, A. N., Bowman, N. A., Seifert, T. A., & Wolniak, G. C. (2016). How college affects students: 21st century evidence that higher education works (1 vol.). John Wiley & Sons

McMillion, R. (2004). Student loan default literature review. TG Research and Analytical Services. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED542512.pdf

Mezza, A., Ringo, D., Sherlund, S., & Sommer, K. (2019). Student Loans and Homeownership. Journal of Labor Economics. https://doi.org/10.1086/704609

Monaghan, D. B., & Attewell, P. (2015). The community college route to the bachelor’s degree. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(1), 70–91. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373714521865

Mueller, H. M., & Yannelis, C. (2019). The rise in student loan defaults. Journal of Financial Economics, 131(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2018.07.013

Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity: Why having too little means so much. https://doi.org/10.1002/scin.5591840820

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (2019). Some college, no degree: A 2019 snapshot for the nation and 50 states. Author. https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SCND_Report_2019.pdf

Nguyen, M. (2012). Degreeless in Debt: What Happens to Borrowers Who Drop Out. Charts You Can Trust. Education Sector

Oreopoulos, P., & Petronijevic, U. (2013). Making college worth it: A review of research on the returns to higher education (No. w19053). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w19053.pdf