Abstract

Learning to write in middle school requires the expansion of sentence-level and discourse-level language skills. In this study, we investigated later language development in the writing of a cross-sectional sample of 235 upper elementary and middle school students (grades 4–8) by examining the use of (1) lexico-grammatical forms that support precise and concise academic writing and (2) paragraph-level structures for organizing written discourse, known as micro-genres. Writing studies typically elicit and analyze long compositions, instead the present study employed two brief writing tasks that allowed for the evaluation of language skills while minimizing the influence of topic knowledge and other non-linguistic factors. Results of structural equation modeling revealed that the two facets of language proficiency studied—lexico-grammatical skills and skill in producing paragraph-level structures (micro-genres)—represented distinguishable dimensions of productive language skill in this sample. On both dimensions, older writers (grades 6–8) demonstrated greater skill than 4th and 5th graders. These findings, which provide an initial proof of concept for the use of short writing tasks to study language skills that support academic writing, are discussed in relation to writing theory and pedagogy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In middle grade classrooms, students often demonstrate their grasp of curricular content through writing, a task that explicitly hinges on having sufficient content mastery. What is rarely acknowledged is that writing to communicate learning is also a linguistic task, which depends on having a host of language resources. Often as unfamiliar to adolescent writers as the content, the language necessary to convey thinking and learning constitutes an implicit curricular demand in the middle grade classroom. In fact, learning to write at school necessarily involves acquiring new school-relevant language resources, which differ from those needed to participate in day-to-day conversations (Corson, 1997). For instance, at the lexico-grammatical level, developing academic writers need to expand their lexicon (e.g. academic and abstract vocabulary) and their range of morpho-syntactic options (e.g., extended noun phrases, center-embedded clauses) to convey information precisely and concisely (Crossley, Weston, Sullivan, & McNamara, 2011). At the discourse level, novice writers must learn, among other skills, to produce academic text types or micro-genres. We define academic micro-genres as discourse-level organizational structures used prevalently in academic texts to accomplish particular rhetorical functions (e.g., to compare-and-contrast, to enumerate, to classify) (for additional discussion see Biber, 1988 or Biber & Conrad, 2009). Micro-genres constitute the building blocks of macro-genres, such as the persuasive essay or the scientific report (Martin & Rose, 2007; Woodward-Kron, 2005).

Even when composing short texts, writers simultaneously draw on all of these linguistic resources. It is, therefore, surprising that developing writers’ lexico-grammatical skills have been infrequently studied alongside their mastery of text organization structures, which is the approach we take in this study (for notable exceptions, see Berman & Nir-Sagiv, 2007 and Uccelli, Dobbs, & Scott, 2013). Using two short, academic writing tasks, we collected data from a cross-sectional sample of 235 students in grades 4–8 with the goal of exploring and modeling the relationship between writers’ lexico-grammatical skills and skill in producing discourse-level organizational structures within- and across-grades. More specifically, we investigated the underlying latent structure of these two sets of skills by analyzing students’ performances across these academic writing tasks. Having modeled the relationship between these two constructs, we explored, first, whether lexico-grammatical and discourse-level organization skills functioned as a unitary or multi-dimensional construct in a population of developing writers. Then, in an application of Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) modeling, we examined whether students in upper grades, on average, demonstrated greater proficiency in these skills.

We focus on students in the upper elementary and middle grades because curricular writing requirements increase dramatically beginning in fourth grade, making early adolescence a critical period to explore. While limited but insightful prior research documents differences between the school-relevant written language skills of students in middle childhood and pre-adolescence (Berman & Nir-Sagiv, 2007), this study augments this prior research by exploring a continuum of grades (4–8). In light of the widespread tendency to focus almost exclusively on vocabulary expansion in instructional contexts (Scott & Balthazar, 2010), this study aims to raise awareness of the multiple language skills that must be cultivated in synchrony to support developing writers in grades 4–8 as they tackle increasingly challenging academic writing tasks. Rather than study academic language proficiency primarily through the lens of vocabulary skill (lexical skills), which situates language learning as an accumulation of word-specific knowledge, we examine academic language proficiency as an outcome of the synchronous expansion of a broader constellation of language skills that support classroom communication (Uccelli et al., 2014, 2015). While these approaches are complementary, a vocabulary lens emphasizes language learning as an accumulation of words and an academic language lens emphasizes language learning as an expansion of context-dependent language uses. Given our orientation, we employed two short, academic writing tasks designed to elicit an array of school-relevant language skills. Methodologically, this study serves as an initial ‘proof of concept’ for the use of these short, academic writing tasks as a context for students to display their productive academic language skills. We hypothesize that tasks like these may offer more homogeneous assessment conditions than the extended writing tasks commonly used to examine students’ development of school-relevant language skills.

Short writing tasks for the assessment of productive academic language skill

Short writing tasks: a methodological departure

The two short writing that we employed in this study required minimal text production to capture students’ skill in two language domains germane to academic writing development: (1) the production of lexico-grammatical features that support precision and conciseness; and (2) the recognition and production of paragraph-level structures for organizing discourse, or micro-genres, prevalent in expository texts. As a result, this study represents a methodological departure from previous work, which has generally used long compositions to examine adolescents’ written language skills (Bar-Ilan & Berman, 2007; Beers & Nagy, 2011; Graesser, McNamara, Louwerse, & Cai, 2004; Halliday & Hasan, 1976; Woodward-Kron, 2005).

Of course, we acknowledge that long compositions constitute a more authentic elicitation method for analyzing students’ writing skills given that these compositions mirror the multi-componential nature of writing and provide rich insight into how students coordinate linguistic and non-linguistic resources (e.g. content knowledge, orthographic skills, and self-regulatory resources involved in idea generation, idea development, and planning) (Myhill, 2009). As a result, the language skills displayed in a particular piece of extended writing are presumably also affected by the variability in non-verbal domains across writers (such as topic knowledge, working memory capacity, cognitive planning skills, among others). For instance, a writer with sophisticated lexico-grammatical skills might not be able to display the full extent of her ability because the topic chosen is too unfamiliar and her capacity for essay planning underdeveloped. To investigate written language skills while reducing, as much as possible, the influence of topic knowledge and of other non-linguistic factors that presumably affect the language skills displayed in traditional, long-composition tasks (Myhill, 2009), we designed the two tasks used in this study. These two tasks elicited short, written responses about content that was highly familiar to students and required minimal original idea generation. Specifically, we asked students in this study to produce: (1) definitions of well-known words, and (2) one-sentence continuations of paragraphs (academic micro-genres) about highly familiar topics. Whether these minimal tasks would be sensitive enough to capture within- or across-grade variability in sentence-level and discourse-level skills formed the first important question in this study.

Short writing tasks: a theoretical departure

When operationalized, written language proficiency is typically measured as a global construct (as captured by holistic rubrics) or as a finite set of language skills (lexicon, syntax, morphology) with minimal attention to the writer’s skillfulness in deploying language in response to a particular social context (Geva & Farnia, 2012; Hoover & Gough, 1990; Perfetti & Stafura, 2014). For instance, standardized measures of written expression make use of short writing tasks, such as sentence combining or sentence formulation [the Oral and Written Language Scales (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1995); Wechsler Individual Achievement Test-III (Wechsler, 2002)], but do not place particular emphasis on purposefully eliciting language resources that are of high utility in school-relevant expository writing. Inspired by research on academic language (Uccelli et al., 2014, 2015), our study explores the possibility that tasks targeting writers’ skills in using features prevalent in school texts might lead to a closer match between the language skills assessed and those required for successful academic writing. Informed also by the research in reading comprehension in which various facets of academic language knowledge (for example morphology, vocabulary depth and breadth, and syntactic knowledge) have been independently explored as contributors to skilled reading (Lesaux & Kieffer, 2010; Ouellette, 2006; Sánchez & García, 2009; Uccelli et al., 2014, 2015), this study seeks to offer an initial exploration of the distinct language skills involved in academic writing so that future research might explore them as potentially independent contributors to skilled writing.

Lexico-grammatical and discourse organization skills: productive academic language skills

While middle school teachers tend to focus primarily on the more apparent low-level encoding skills, supporting developing writers in the more complex mastery of advanced sentence-level and discourse-level language skills is of critical importance (Berman & Nir-Sagiv, 2007; Berninger, Cartwright, Yates, Swanson, & Abbott, 1994); yet, we still lack research that can inform the design of this instruction. Here we explore a select set of sentence- and discourse-level linguistic skills that support skilled expository writing: (1) lexico-grammatical skills and (2) skill in producing paragraph-level organization structures prevalent in expository texts, known as micro-genres. Below we discuss prior research that sheds light on the development of these skills for adolescent writers and their measurement in prior studies.

Lexico-grammatical skills: development and measurement

To examine lexico-grammatical skills, we focus on two subconstructs conceptualized as key components in the development of academic writing ability: skills in lexical precision and morpho-syntactic conciseness. We selected these two key facets for their relevance in one particular context: school writing. We measured these skills by eliciting written academic definitions of high-frequency words that we expected to be familiar to participants, and by subsequently, scoring responses for the degree of superordinate precision and morpho-syntactic complexity. While our measurement approach is novel, these components have been examined in prior studies undertaken in developmental linguistics.

Lexical precision

It is well-documented that developing writers gradually employ more complex and abstract vocabulary throughout the school years, especially in expository writing, where information must be communicated precisely. For instance, Berman and colleagues’ comparison of the expository texts written by English-speaking students in four age groups (10, 13, 17, graduate students) finds that older writers’ texts contain a higher mean number of academic vocabulary words (Bar-Ilan & Berman, 2007; Berman & Nir-Sagiv, 2007; Berman & Verhoeven, 2002). Of particular note, the use of abstract language, especially the use of nominalizations or nouns formed by shifting the grammatical category of verbs and adjectives (words like ‘destruction,’ ‘freedoms,’ ‘perceptions,’ and ‘assimilation’), has been shown to increase with age. Linked with expository writing quality for students in grade 4 (Olinghouse & Leaird, 2009), grade 5 (Olinghouse & Wilson, 2013), and in high school (Uccelli et al., 2014, 2015), nominalizations (when used correctly) support the discussion of abstract topics like those that are part of middle grade curricula. Writers also signal a growing awareness of the discourse conventions of different genres through their use of lexical components, with students in grade 5 employing more sophisticated, diverse vocabulary in their persuasive essays than in their narrative or informational writing (Olinghouse & Wilson, 2013).

Morpho-syntactic complexity

As the communicative demands of the classroom increase, developing writers are not only acquiring lexical skills, they are also developing the morpho-syntactic skills needed to pack multiple ideas into relatively few sentences. More experienced academic writers, for example, tend to employ more subordinate clauses (e.g., ‘A debate is an argument which features two opposing points of view’). Prior research documents that the proportion of subordinating clauses used in writing appears to increase at least through grade 8. Moreover, Scott and others note that the depth of their interdependence (i.e., the level of embedding of a subordinated clause) increases across development with adult writers often embedding as many as three or more clauses into a single sentence (Crowhurst, 1980, 1987; Nippold, Ward-Lonergan, & Fanning, 2005; Rubin, 1982; Rubin & Piche, 1979; Scott, 2004). This skill tends to be deployed mostly in crafting expository texts, which have been shown to contain a higher number of relative and adverbial clauses than narratives (Nippold, Hesketh, Duthie, & Mansfield, 2005). Similarly, when compared to oral conversations, expository writing also makes greater use of extended nominal groups (Beers & Nagy, 2011; Berman & Nir-Sagiv, 2007; Scott & Windsor, 2000). For example, head nouns appearing in written texts are frequently accompanied by pre-modifiers like adjectives (e.g., ‘a regulated discussion…’), or by post-modifiers like prepositional phrases (e.g., ‘a regulated discussion of a proposition…’). Like other syntactic skills, the incidence of complex noun phrases incrementally develops from age 9 to 12 years, and especially from age 16 on (Ravid & Berman, 2010). In contrast to lexical sophistication, the relationship between writing quality and syntactic complexity appears indirect with longer sentences failing to equate universally with ‘better’ writing across genres and age groups (Beers & Nagy, 2009; Crowhurst, 1987). We examine these skills not because they are linked with writing quality. We focus, instead, on morpho-syntactic skills because they are instrumental for communicating abstract ideas and thinking in academic contexts (Scott, 2004).

Capturing lexico-grammatical development: definition production task

In the existing literature, one task that provides insight into students’ skills in lexical precision and morpho-syntactic conciseness (or lexico-grammatical skills) is the definition production task. Like other academic text types, producing an academic definition requires linguistic resources for precise and concise written communication. Written academic definitions, for instance, call for the use of precise lexicon in the form of a superordinate that indexes the taxonomical category of the word (i.e., a horse is an animal, anger is an emotion) and for the use of complex morpho-syntax (nominalizations, extended noun phrases, center-embedded clauses) (Marinellie, 2009; Marinellie & Johnson, 2004).Footnote 1 In contrast to other school-relevant genres, the definition requires the production of these conventional features within the confines of a particularly compact text. Despite their brevity, prior research documents a significant positive relationship between language skill as displayed in a definition task and literacy achievement at school (Benelli, Belacchi, Gini, Lucangeli, 2006; Gini, Benelli, & Belacchi, 2004; Snow, Cancino, & Gonzalez, 1989). On the basis of this relationship, we argue for the use of definition tasks like the one used here to efficiently examine a subset of school-relevant language skills in writing research. Certainly, we are not making the argument that the minimal definition genre offers insight into all of the linguistic skills that support expository writing; rather, we suggest that many of the lexical and morpho-syntactic skills that support students in writing academic definitions also support them in producing expository texts (Uccelli, Galloway, Barr, Meneses, & Dobbs, 2015).

In this study, we asked students to define eight high-frequency nouns. Our goal was not to assess students’ depth of word knowledge. Instead, the goal of this study was to assess participants’ skills in producing the language of academic definitions in the context of words whose meanings they knew well (bicycle, horse, hospital, calendar, music, winter, debate, anger). Trained raters scored the definitions for the degree of superordinate precision and morpho-syntactic structural density, areas for which developmental progress relevant for academic writing writ large has been documented (Berman & Nir-Sagiv, 2007; Kurland & Snow, 1997; Snow, 1990). By assessing definitional skill using known words, we question the assumption that knowledge of a word’s meaning is sufficient to successfully produce its academic definition. In fact, to successfully craft a high-quality academic definition, writers need the additional language skills captured by our scoring system.

Our approach differs from those studies that use definition production tasks to measure vocabulary depth as one aspect of vocabulary knowledge. (Ordóñez, Carlo, Snow, & McLaughlin, 2002). Vocabulary depth refers to the depth of knowledge about specific words and encompasses morphological, semantic, and syntactic awareness (see Proctor, Silverman, Harring, & Montecillo, 2012). In other words, using a definition task to measure vocabulary depth entails assessing a participant’s multiple sources of knowledge about a word’s form and meaning across all contexts of use; In contrast, in our definition task we focus on eliciting the context-specific language learning that is happening in school settings (Uccelli et al., 2014, 2015).

Given our goals in this study, both the selection of words for the definition task (we selected only high-frequency and familiar words that we expected participants to know well) and the scoring of the definitions (a lexical precision scale, and a morpho-syntactic structural density scale) focus our attention on how skilled students were at expressing the word’s meaning through precise and concise language, not on how much they knew about the word. When scoring definitions to capture vocabulary depth, the focus is word-specific and scoring captures the writer’s knowledge of a single word’s meanings (see for example Ordóñez et al., 2002). In contrast, we conceptualize the skills elicited through our definition task not as word-specific, but as indexing a more general level of skill in school-relevant precise and concise communication; hence, we scored all definitions in this study using a single scoring system that can be applied in future studies regardless of the nouns being defined.

Although in reality vocabulary depth and lexico-syntactic skills that support precision and conciseness are most likely highly correlated; theoretically, it is possible to distinguish them. It is conceivable, even if unlikely, that writers with small vocabulary repertoires and low-levels of vocabulary depth might have learned to produce the small set of precise superordinates and the complex morpho-syntactic structures called upon in defining the familiar words selected for our task. After all, our task does not require sophisticated vocabulary knowledge. Participants need to know only high-frequency superordinates (most of them already learned by grade 4 according to Biemiller, 2010) to display skill in our task, e.g., animal/mammal (horse), vehicle (bike), emotion/feeling (anger), season (winter). Certainly, though, one would expect vocabulary depth to be positively associated with lexical precision and morpho-syntactic conciseness as measured in this study.

Discourse organization skills: development and measurement

In addition to lexico-grammatical skills, the present study examined students’ skill at recognizing and producing micro-genres found in various school-related expository texts. We focus on four micro-genres prevalent in school texts (classification, compare-and-contrast, enumeration, argument-and-counter argument) that are often marked with connectives (Meyer, Brandt, & Bluth, 1980). Drawing from Britton (1994), we view connectives as devices for linking ideas (as in the cohesion research tradition) and for explicitly marking the rhetorical structures of micro-genres. Connective devices function as cues to the reader and can be understood as providing instructions about how to make meaning of the text (Sánchez & García, 2009). For example, connectives in a text alert readers to a compare-and-contrast text structure (In contrast…; On the other hand…) or, alternatively, to an enumeration text structure (First…; Second…). In this study, we explore whether young writers, when presented with a partial text that signals the beginning of a micro-genre through explicit connective devices, will continue the paragraph in a way that is consistent with the given micro-genre. Specifically, we examine how students’ responses demonstrate awareness of discourse-level text structures typically marked by connectives in micro-genres often found in academic texts.

The use of connective devices begins, for some writers, as early as second grade (King & Rentel, 1979) and continues to develop into late adolescence, and even into the college years as writers expand their range of options to express relationships between ideas across different disciplines (Craswell & Poore, 2012; McCutchen & Perfetti, 1982; Crowhurst, 1987; McCutchen, 2000). Particularly illuminating is Myhill’s comparison of connective usage in paragraphs written by 13- and 15-year olds (2009). This research suggests that much individual variability exists in the types of connectives deployed within each age group. She found that it was not the writer’s age, but rather her level of writing skill that was linked with the use of fewer temporal connectives, like those common in oral and written narratives (then, next), and a higher frequency of additive (additionally, as well as) and adversative (however, on the other hand) connectives, which are more commonly found in expository texts. Moreover, recent research suggests that the skill to organize academic micro-genres is a key component of the school-relevant rhetorical competence required for advanced literacy tasks (Sánchez & García, 2009). Woodward-Kron (2005), for example, in an examination of undergraduate writers found that the taxonomic organization of micro-genres within exposition a macro-genre provided the writer with the chance to clarify, restate or explain a phenomenon or concept either to herself or to demonstrate her understanding to the reader. Woodward-Kron suggests that these micro-genres were not only helpful to writers in communicating clearly with readers, but also served to support content learning for writers.

Capturing discourse organization skills: the paragraph continuation task

To capture these discourse organization skills, we borrow from a research-based task used by a prior study conducted by Sánchez and García (2009): a discourse-level text continuation task. This task asked students to write a single sentence to continue an academic micro-genre. Drawing from Sánchez and García (2009), we hypothesized that asking students to continue a text that has an established rhetorical structure (compare-and-contrast or enumeration, for instance) simultaneously requires the ability to recognize the text’s rhetorical function and to use this knowledge to produce text-continuations. For example, in the present study, students were asked to continue this text:

Riverland is a town located next to a large river. The river provides three important resources: clean water, fresh fish, and nice beaches. First, residents in Riverland are able to drink clean and safe water from the river.

Students received full credit if they provided a continuation that showed understanding of this as an enumeration text, for example, ‘(Second) (Also) (In addition), residents can eat fish from the river….’. Sánchez and García (2009), who employed a similar task in Spanish to explore the relationship between knowledge of micro-genres, which they call ‘top-level structures,’ and reading comprehension skill, found that this task accounted for individual variability in text comprehension. In contrast, we use this task as an indicator of students’ recognition of and skill at producing micro-genres when writing. The present approach, which cued four specific rhetorical structures, differs from other studies such as the work of Woodward-Kron (2005), who examined micro-genre skill using a writing prompt. In an open elicitation task, students draw on those micro-genres that best accomplish their rhetorical goals. As a result, such open-ended elicitation methods can only provide evidence of the writer’s skill in producing the micro-genres she has chosen to display without offering any evidence about her skill in producing micro-genres absent from a specific piece of writing. Because of our interest in examining students’ skills to recognize and produce specific, school-relevant micro-genres, we opted to select a pre-specified set of highly-prevalent academic micro-genres to be tested through this task.

The present study

The present study was designed to examine the relationship between two facets of language skill (lexico-grammatical skills and skill to produce structures for organizing micro-genres) that support expository writing in upper elementary and middle grade populations. Prior cross-sectional research has documented concurrent upward trends in these two facets of language proficiency for developing writers (Berman & Nir-Sagiv, 2007); but, to our knowledge no prior studies quantitatively investigate their dimensionality. These skills may develop in synchrony and comprise a unitary dimension, perhaps as an artifact of the simultaneous use of these word, sentence, and discourse features in the texts that students read and write. In contrast, we can also imagine skill in producing local linguistic features that facilitate concise and precise communication and skill in structuring micro-genres may be interrelated processes that draw from a substratum of common knowledge, yet represent distinct discourse competencies for novice writers.

It is also possible that this relationship is dynamic and changes across development. Text organization patterns at the discourse-level are not always explicitly marked through connective devices in the writing of experts, who have more linguistic resources that can be marshaled to signal how ideas are connected; but research suggests that young writers depend more heavily on connectives to signal intersentential relationships (Crossley et al., 2011; Verhoeven & van Hell, 2008). This developmental shift mirrors the argument made by Halliday (1993) that as writers develop expertise, their texts move from grammatical density to lexical intricacy, with word-level and sentence-level competencies appearing to be distinct, though interrelated in adult writers. We have little knowledge of whether these linguistic aspects of expository text generation (lexico-grammatical skills, skill in discourse-level structures for organizing micro-genres) function as a unitary or multi-dimensional construct in populations of developing writers, who have fewer language forms available and enact a smaller range of communicative functions. In this study, we examine this relationship. This study cannot illuminate the factors associated with these language skills; yet by making use of confirmatory factor analysis, an approach discussed in greater detail below, this study does give insight into the dimensionality of these skills in a cross-sectional sample (grades 4 to 8). In addition, this study provides insight into the between-grade variability in these language skills as exhibited in fourth- to eighth-grade writers.

Method

Participants

A cross-sectional sample of fourth- to eighth-grade students attending one urban K-8 school in the Northeastern United States participated in the study (n = 235). All demographic data were provided by the school district (see Table 1). Free-or reduced-price lunch data indicated that the majority of students were from low-income families (80 %). Eighteen percent of students were officially classified as English Language Learners,Footnote 2 and a larger number (28 %) were identified as language minority students, from a wide range of language backgrounds (Haitian Creole, Spanish, Portuguese, Somali, French).

Measures

We designed the tasks used in this study following an iterative process of engaging with the literature discussed above and pilot testing item types with students.

Written academic definitions | lexico-grammatical skills

As described above, this group-administered task elicited students’ written dictionary-like definitions with the goal of assessing students’ lexico-grammatical skills. The goal of this task was not to measure students’ knowledge of word meanings, but instead to evaluate their deployment of lexical and morpho-syntactic skills in the context of defining the meaning of familiar nouns. Because previous studies asked students to define 8-10 words (see Marinellie, 2009; Kurland & Snow, 1997), we selected 8 nouns for this task (bicycle, horse, hospital, calendar, music, winter, debate, anger). To support students in understanding the expectations of the task, the administrator read aloud a scenario about two adolescents producing a dictionary for adults and provided an oral example of an academic definition. Participants were instructed to: “Please, write what each word means. Remember that your definitions are for a dictionary for adults.” We provided no information to students about the part of speech they should define (‘debate’ and ‘bicycle’ could be defined as nouns or verbs), although only noun definitions were scored in this analysis.

In addition to selecting only nouns that have been used as stimulus items in prior definition production studies (with the exception of ‘debate’), two criteria guided our word selection. First, in order to better capture students’ skills at producing academic language while minimizing the influence of non-verbal factors, we chose words that were familiar to students. All words were selected from the WordZones™ for 4,000 Simple Word Families (http://textproject.org/teachers/word-lists/), which is a list of the most common 4,000 word families that account for 80 % of the words in school texts (Zeno, Duvvuri, & Millard, 1995). To confirm that students indeed knew the meanings of the words we selected for the task, we conducted an initial pilot study with a cross-sectional sample of students in grades 4–8 (n = 32). Our second consideration was the noun’s level of abstraction. Given prior research suggesting that students demonstrate different levels of language skill when defining concrete versus abstract words (El Euch, 2007; McGhee-Bidlack, 1991; Nippold, Hegel, Sohlberg, & Schwarz, 1999), we selected words on a continuum from more-concrete to more-abstract. Fundamentally, we sought to create task demands that would mirror the challenges that writers face in the secondary classroom, where writing about abstract topics is commonplace. Broadly speaking, concrete nouns refer to objects or places that can be easily visualized and touched; whereas abstract nouns refer to more intangible entities (El Euch, 2007; Nippold et al., 1999). Concrete, highly-imageable entities are easier to learn and are often explicitly taught by caregivers to our youngest learners. Acquired early in development, the vocabulary and superordinate knowledge needed to describe concrete nouns is likely readily accessible to middle graders (Maguire, Hirsh-Pasek, & Golinkoff, 2006). In contrast, we would expect that students may struggle to generate the academic lexico-grammatical structures examined here when writing definitions of more abstract nouns, even if these nouns’ meanings are highly familiar to them (e.g., winter, music). In fact, this pattern emerges in a study of 10, 14 and 18-year olds, in which older learners produced more superordinates and more informative oral definitions for concrete than for abstract nouns (McGhee-Bidlack, 1991). We conceptualize the challenge of defining more abstract nouns as being analogous to the increasing difficulty that students may encounter when faced with writing about more abstract topics in middle grade classrooms (e.g., writing about power generation using wind turbines in science or the causes of the Franco-Prussian war in social studies).

To select nouns representing differing levels of concreteness, we first collected concreteness ratings for each of the eight words from two psycholinguistic databases (Coltheart’s MRC Database, 1981; Byrsbaert’s database, Brysbaert, Warriner, & Kuperman, 2014). Then, we applied a scale provided by Berman and Nir-Sagiv (2007) (adapted from Ravid, 2006) for determining levels of noun abstraction to each of the nouns we selected (Level 1 = most concrete, Level 4 = most abstract). On the basis of an integration of prior abstractness coding and ratings, we generated three levels of abstraction to classify the nouns used in this study: level 1 nominals, which refer to individuated, perceptible, and stable physical entities or objects (e.g., bicycle); level 2 nominals, which refer to perceivable yet intangible entities (e.g., winter); and level 3 nominals, which refer to abstract, less individuated, non-imageable nouns (e.g., anger).

Producing paragraph continuations | discourse-level organizational skills

In order to assess recognition and production of highly prevalent academic micro-genres, participants were presented with four partially-completed paragraphs and instructed to write the ‘sentence that could come next.’ The texts simulated four typical rhetorical structures in academic writing: enumeration, classification, compare-and-contrast, and argument-and-counterargument (Paltridge, 2012). Designed to signal particular patterns of text organization, each text fragment displayed overt marking of these organizational patterns through connectives (Halliday & Hasan, 1976; Vande Kopple, 1985). As noted above, we drew inspiration from Sánchez and García’s (2009) elicitation task, which was administered to middle school Spanish-speaking students and revealed considerable individual variability. In this study, we read the task aloud to students to reduce reading comprehension demands and to mitigate the impact of reading difficulties on students’ writing performance.

Procedures

Trained research assistants administered the two writing tasks (eight noun definitions and four discourse-continuation tasks) on contiguous days as part of a larger academic language battery. To maintain the format used for regular instruction, students were assessed in their classrooms at the participating K-8 school. A trained administrator read all tasks aloud to students in an effort to minimize the impact of decoding ability on task performance.

Scoring of researcher developed tasks | definition task

To take advantage of the automated computer analysis programs of the Child Data Exchange System (CHILDES), we transcribed students’ definitions using the CHAT (Codes for Human Analysis of Transcripts) format (MacWhinney, 2000). To maintain an authentic record of the original writing, we registered misspellings in a separate coding tier. Given our focus on language knowledge—not on spelling—all definitions were scored as if they had been written with conventional orthography. Using a research-based and data-driven scoring system, we scored definitions for various elements of academic texts: degree of superordinate precision, structural density (i.e., morphosyntactic complexity), and informativeness (content features included in the definition) (for more information on this scoring manual, see Uccelli et al., 2014). Each word received three scores:

Superordinate precision (SP)

We developed a five-point scale (0–4) to measure the presence or absence of a class specific term and its level of precision (see the Superordinate Precision Scale in “Appendix”). For example, labeling horse as ‘animal’ or ‘mammal’ was scored as a higher definitional performance than labeling horse as ‘something,’ in that the former superordinate was more precise (Snow, 1990). Students received full credit for providing an accurate superordinate both for concrete and abstract words. For instance, students would receive the maximum score if they provided ‘emotion’ or ‘feeling’ as the superordinate for anger; but only partial points if they offered a synonym, such as ‘fury’ or ‘outrage’. Multiple superordinates qualified for the maximum score for each word and when applicable, phrases were also scored as correct (for example, both ‘vehicle’ and ‘a means of transportation’ were accepted for the word, bicycle).

Structural density (SD)

We used a seven-point scale (0–6), to capture morpho-syntactic complexity (see the Structural Density Scale in “Appendix”) in students’ definitions. Using the formal structure of definitions as a reference point {i.e., genus (superordinate) + differentia (compact syntactic clauses or phrases) (Scott & Nagy, 1997)}, we developed this theory-based and data-driven scoring system to capture the presence of extended noun phrases, embedded clauses, passive voice, and nominalization, among others.

Informativeness (IN)

We developed a three-point scale to measure the number of appropriate content features given in each definition. We awarded one point for each type of conceptual information mentioned (e.g., ‘parts of an object,’ ‘descriptive attributes’ ‘functional properties’) for a maximum of three points.

For each word, students could earn a total score of 0–14 points or 112 points total. This total score represents students’ skill at deploying language features characteristic of academic definitions. We calculated inter-rater reliability for each dimension. Three trained raters scored the definitions and Cohen’s kappa coefficients were above 0.90 for all three dimensions: superordinate precision = .96, structural density = .91, informativeness = .92. In this study, we used the average scores earned on each dimension across the eight items in confirmatory factor analysis. Across this entire sample, internal consistency reliability of items comprising the academic definitions task was adequate for the purposes of this study (Cronbach’s alpha = .67).

Scoring of researcher developed tasks | paragraph continuation task

Each continuation was scored by taking into account two types of information: (1) the presence of an explicit marker of cohesion (e.g., a connective) (2) and sentence content that was topically coherent given the information provided in the previous sentences (see Paragraph Continuations Scoring in “Appendix”). These pieces together constituted evidence that the student had recognized and been able to explicitly mark the rhetorical structure cued by the preceding text (enumeration, classification, compare-and-contrast, argument-and-counterargument). Connectives believed to be familiar to most students (also, though, because), as well as less familiar connectives (consequently, as a result) were accepted as correct answers if they fulfilled the expected function cued by the item (Myhill, 2005). This decision was made because we hoped to capture students’ skill in organizing text patterns and marking them explicitly; thus, if students showed evidence of this skill, we did not penalize them for accomplishing it through a selection of words that were less academic (similarly, they were not rewarded for the use of more academic connectives). Two trained raters scored items on a 1–5 scale, resulting in a total possible score of 20 points (Cohen’s kappa coefficient for reliability = .92). Because the paragraph continuation items had patently non-normal distributions (most students received a score of 1 or 5), these items were recoded as binary variables (answers scored 1–3 = 0; answers scored as 4–5 = 1), an approach advocated in the work of Finney and DiStefano (2006). Because only those responses that warranted a 4 or 5 were ‘correct’ responses, collapsing these scores resulted in no loss of information about student performance. Internal consistency reliability in this sample for the paragraph continuations task was adequate (Cronbach’s alpha = .71).

Analytic plan

Data in this study were analyzed using STATA version 12 and, specifically for the factor analysis portion, Mplus 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). After preliminary analysis of the data to confirm that it was normally distributed in the sample, we made use of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to evaluate the fit of theory-driven models of the relationship between lexico-grammatical skills and skill in structures for organizing discourse (micro-genres). This approach allows for the testing of competing theoretical models using a series of robust fit indices (Bollen, 1989; Brown, 2006). Additionally, working within a CFA framework allowed us to account for the effects of measurement error when estimating student scores on each latent variable resulting in less-biased estimates if the model is specified correctly (Brown, 2006). Because various items included in the analysis were dichotomous, robust weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimation (which uses probit rather than linear regressions and is better suited to dichotomous data) was applied to the matrix of polychoric correlations for the entire sample of students. We then examined the relative goodness of fit of a series of nested models.Footnote 3

We tested for both factor invariance and population heterogeneity of the adopted model by fitting a MIMIC model (Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes) in which the adopted model’s latent factors and indicators were regressed onto a covariate representing group membership (0 = upper elementary school, 4th–5th grade; 1 = middle school, 6th–8th grade) (Muthén, 1989). In the present analysis, using a relatively small sample, MIMIC models were selected as the preferred method for assessing invariance over multiple-group CFA because this method requires smaller sample sizes and offers greater parsimony. However, unlike multiple-group CFA, MIMIC models test only the invariance of factor intercepts and means and require the use of dichotomous indicators of group membership (Brown, 2006). While an insignificant direct effect of the covariate on the latent factor indicates population homogeneity (there are no group differences on latent means), an insignificant direct effect of the covariate on any indicator of the latent factor is evidence of measurement invariance, or a lack of group differences on an indicator’s intercept (Brown, 2006).

Results

Preliminary analyses

We examined the dataset for missing data, outliers, skewness and kurtosis. Prior to completing the analysis, we generated descriptive statistics, including leverage indices and histograms, and found no anomalies or outlying observations. Results suggest that these measures captured variability in language skill across and within each grade (Table 2). Notably, no student in any grade received the maximum number of possible points for the definition task (112 total across the eight words), suggesting that no ceiling effect is present.

Given that some variables were binary,Footnote 4 we generated a polychoric correlation matrix for the observed indicators in the entire population, which is appropriate for binary and ordinal indicators (see Table 3 for polychoric correlations). As noted above, we made use of robust weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimation to estimate the matrices. Inspection of the pairwise correlations revealed that all of the tasks were positively correlated. Tasks measuring lexico-grammatical skill were strongly correlated with one another (in the definition task items), but less strongly with items measuring skill at producing predictable discourse organization structures (in the paragraph continuation task).

Building the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model: a two-dimensional model of productive language skill

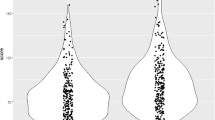

The results of CFA suggested that a two-factor model best fit the data (see Fig. 1). To arrive at this conclusion, we fit a sequence of increasingly complex CFA models that were deemed plausible given prior findings that, as reviewed above, have documented the concurrent developmental progress of the linguistic skills that support skilled writing. Starting from the most parsimonious one-factor model, we added additional factors in a stepwise fashion. We used nested model tests to assess whether the addition of the factor improved the fit of the model. Nested model tests suggested that the two-factor model had a better fit than the one-factor model (X 2 diff(1) = 39.93; p < .0001). Because some controversy exists regarding the use of nested model tests, we tested the discriminate validity of the two-factor model by constraining the correlations between the latent trait factors to 1. The latent variable covariance matrix in this constrained model was not positive, which suggests that the one factor model is not a good fit to the data.

The final model included two unique inter-related dimensions (lexico-grammatical skill and skill in paragraph-level organization structures known as micro-genres) comprised of three and four indicators respectively. In the final model, we found no double-loading indicators and we assumed the measurement errors to be uncorrelated. The latent factors of “lexico-grammatical skill” and “skill in paragraph-level organization structures” were permitted to be correlated to explore associations between these skills based on previous evidence that these facets of written productive skill co-occur in the writing of novices and skilled writers (Berman & Nir-Sagiv, 2007; Scott, 2004).

We assessed the fit of the overall model using common indices including the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). These indices provided different information relevant to assessing model fit (fit relative to a null model, absolute fit, fit adjusted for parsimony of the model). Both the CFI and TLI values exceeded 0.95, indicating good model fit (Brown, 2006). A RMSEA value below 0.08 was deemed acceptable (Brown, 2006).Footnote 5 Each of these indices evaluating overall fit suggest that the two-factor model fit the data well, X 2(13) = 16.919, p = 0.20, RMSEA = 0.04 (90 % CI 0.00–0.08), TLI = 0.99, CFI = 0.99. Furthermore, examination of standardized residuals and modification indices suggested that there were no localized areas of poor fit in the specified two-factor model. In addition, we carefully scrutinized parameter estimates (loadings) to establish convergent and discriminate validity. The standardized factor loadings were all above 0.1 and statistically significant (p < .001), suggesting that the indicators were very strongly related to their purported latent factors (Brown, 2006). Estimates of the between-factor correlation (0.459) indicate a moderate relationship between the dimensions (see Table 4).Footnote 6 In other words, the two facets of language for academic writing examined here appear to be related, but distinct dimensions.

Fitting the MIMIC model: differences between elementary and middle grade writers on each item and dimension

In this analysis, we first evaluated whether evidence of measurement invariance for the intercepts by school level (upper elementary vs. middle school) existed. The MIMIC model provided a good fit to the data {X 2(18) = 18.481, p = 0.42, RMSEA = 0.01 (90 % CI 0.00–0.06), TLI = 0.99, CFI = 0.99} and the inclusion of the grade covariate did not alter the factor structure or result in areas of strain. Table 5 provides selected parameter estimates. When holding the latent factors constant, we found no significant direct effects between grade and the indicators, which suggested that the items did not function differently across the middle (grades 7 and 8) and elementary school (grade 4–6) samples, a result equivalent to intercept invariance in a multi-group CFA framework.

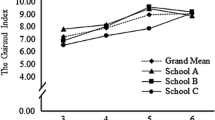

Having established that the items functioned equivalently across samples of middle and elementary students and that the two separate dimensions of productive language skill could be identified, we estimated the mean difference between elementary and middle grade writers’ scores for each latent factor by specifying the same MIMIC model utilized above (the two factors and indicators were regressed onto covariates representing group membership; 0 = elementary school; 1 = middle school). Both paths linking the school-level covariate to the latent factors were statistically significant, suggesting that the latent factor true mean score for elementary grade students is statistically different from that of middle graders for both dimensions.

Specifically, the path from the latent factor ‘lexico-grammatical skill’ to grade was significant (z = 6.48, p < .0001). Middle grade writers’ mean true score on the lexico-grammatical skill latent factor was 0.15 units higher than that of 4th and 5th graders. Standardized parameter estimates function as differences expressed in standard deviation units and can thus be interpreted in the same way as Cohen’s d. Therefore, older students are, on average, 0.48 standard deviation units higher than elementary school students on the latent dimension of lexico-grammatical skill, approximately interpretable as a “medium” effect size under conventional guidelines provided by Cohen (1992). Similarly, for the ‘skill in paragraph-level organization structures’ latent dimension, middle graders also evidenced a higher mean (z = 4.71, p < .0001); though the effect size is smaller (standardized parameter estimate = .36) (see Table 5). Because these tasks are experimental and because the skills they measure have not received previous quantitative study in cross-sectional populations, it is not possible to interpret these effect sizes.

Estimates of participants’ factor scores from the CFA model allows for description of cross-sectional differences by grade on both dimensions. These results suggest that students with more years of formal schooling demonstrated greater skill at generating texts that were precise and concise as a result of increased lexico-grammatical skill (Fig. 2) and that followed expected patterns of expository text organization at the discourse-level (Fig. 3).

Discussion

This study joins prior studies that find intra-individual differences across levels of language (word, sentence, and text) (Abbott & Berninger, 1993; Abbott, Berninger, & Fayol, 2010; Berninger & Abbott, 2010; Whitaker, Berninger, Johnston, & Swanson, 1994); but, augments this prior research by focusing on the context-specific deployment of school-relevant language—or academic—language skills, rather than on written language skills operationalized as a general competence. This cross-sectional study used two short writing tasks that were designed to elicit a subset of skills relevant for academic writing. Our goal was to examine the relationship between lexico-grammatical skills and skill in producing common paragraph-level structures for organizing expository texts (micro-genres) in a sample that covers a continuous span of students from grades 4–8. Findings revealed that despite their minimal nature, these two brief tasks were sufficiently sensitive to capture within-grade and across-grade variability in these school-relevant language skills. Further, our analysis suggests that while related, lexico-grammatical and discourse-level organization skills as measured by these tasks, which we designed to capture only a subset of the skills that might comprise the wider universe of productive language skills needed for academic writing, function as distinctly identifiable dimensions of school-relevant language proficiency. Evidence for this claim comes from the low latent correlation (.46) between these two dimensions, from which item-specific measurement error has been partialed out, offering a relatively rigorous test of their independence.

We cannot fully contextualize our results in prior research because our study represents a first attempt to conceptualize and operationalize these constructs in this way; however, a few prior studies support our findings. Mirroring the moderately low correlation between the latent dimensions observed in this study, Uccelli, Dobbs and Scott (2013) note that lexical and grammatical measures were not significantly related to essay-based measures of discourse organization in a sample of high-school students. In contrast, examination of the latent factor for lexico-grammatical skills (a composite of skills in lexical precision and morpho-syntactic conciseness) suggests that the skills needed to achieve precision and concision are closely coupled for the middle grade writers in our sample. Germane to the present study, Uccelli et al. (2013) also find a strong correlation (0.73) between essay-based lexical diversity and syntactic complexity on observed measures of these skills in persuasive essays written by linguistically and socio-economically diverse high schoolers (Uccelli et al. 2013). This finding that lexical and syntactic development go hand-in-hand is also echoed in the work of Ruth Berman (2004). Despite using different task types to capture these skills, these studies collectively suggest that the skills that support preciseness and conciseness are intertwined, but distinct from those skills needed to organize multiple sentences into a cohesive text for adolescent writers. While skillful middle grade writers demonstrate proficiency on both dimensions, uneven patterns of skill may characterize the writing of less-skilled or less-expert writers, who may, for example, be able to use language to convey information precisely and concisely without being able to effectively use familiar patterns of text organization.

Drawing from prior studies of academic language learning, we anticipated that being immersed in the literate environment of the classroom would lead to growth in these context-specific language skills (Ravid & Tolchinsky, 2002; Schleppegrell, 2004). Our finding that older writers with more years of cumulative schooling produced written responses that displayed a higher degree of lexical precision, morpho-syntactic complexity, and greater skill in the production of academic micro-genres than younger writers confirmed our hypothesis and speaks to the usefulness of the tasks employed in this study to capture this context-specific language development. Curiously, these results suggest that the magnitude of difference in lexico-grammatical skill between students in the earlier grades (4th–5th) and those in later grades (6th–8th) was greater (a moderate effect size) than the magnitude of difference in skill in discourse-level organization of micro-genres between these two groups (a smaller effect size). This observed difference in effect sizes may be a consequence of the tasks—or may offer insight into the timetable in which these skills develop. Alternatively, this might also be the result of the size of the dimension-specific learning space. In other words, the lexico-grammatical dimension might potentially encompass a much larger learning area—with numerous lexical items and morpho-syntactic structures to be learned—than the relatively limited set of prevalent discourse-level structures that comprise the dimension of academic micro-genres organization.

Methodologically, this study is a departure from prior studies, which examine these skills through the elicitation of extended texts (Bar-Ilan & Berman, 2007; Berman & Ravid, 2009). We argue that data collected through traditional elicitation methods conflates linguistic skills with background knowledge and cognitive skills and, in so doing, might lead to the underestimation of writers’ language skills. For example, writers with advanced linguistic skills might produce linguistically simplistic texts as the result of insufficient topic knowledge. Moreover, with open-ended elicitation of extended texts, the analysis can only make claims about the language resources that writers opt to spontaneously produce in their responses. The two short, structured writing tasks used in this study appear to offer insight into students’ productive language skills, while minimizing the multiple non-linguistic demands posed by text generation. These tasks also enable the targeted assessment of predetermined language resources intentionally elicited for their relevance to support academic writing. Some evidence for the validity of this approach rests in the parity between our results and those found in studies that analyzed full essays produced by writers at different developmental points (Beers & Nagy, 2009; Berman and Nir-Sagiv, 2007; Crossley et al., 2011; Snow, 1990). For instance, in a study examining both linguistic features and global discourse structure in longer expository texts, Berman and Nir-Sagiv (2007) find significant differences across measures when contrasting the language skills of 4th graders with those of 7th graders. Our findings confirm and extend these results by looking at a continuum of upper elementary and middle school grades (4th–8th grade) and by offering more homogeneous task conditions for students to display their language skills.

The use of tasks that target particular language resources is of great utility when we consider the possibilities for examining these skills in relation to writing proficiency. Though research in reading comprehension has explored multiple facets of academic language knowledge (morphology, vocabulary depth and breadth, and syntactic knowledge) as independent contributors to skilled reading (Uccelli et al., 2014, 2015; Lesaux & Kieffer, 2010; Ouellette, 2006; Sánchez & García, 2009), this approach has rarely been taken in the field of writing research because of the challenge of assessing writing sub-skills in isolation. This study has yielded two dimensions of language skill—captured by two distinct tasks—that might be examined as independent contributors to skilled writing. For the field of adolescent literacy research—where many instruments exist to measure students’ lexical (vocabulary skills)—the tasks used in this study are insightful given their potential for illuminating how a wider array of language skills unfold. In particular, these tasks allow us to measure school-relevant syntactic skills and discourse-level organization which are difficult to assess (Scott, 2010).

This orientation towards measuring school-relevant language skills distinguishes our approach from operalizations of language proficiency that index these skills by examining students’ vocabulary skills. Instead of entering the analytic space of language proficiency through a focus on vocabulary, which emphasizes language learning as an accumulation of word-specific knowledge that expands in concentric circles (that eventually overlap); we enter the space through a focus on language use and social context, which emphasizes language learning as the synchronous expansion of a constellation of language skills as the result of using language in particular contexts (Uccelli et al., 2014, 2015). We can envision a productive research agenda that builds upon the foundations of this study by seeking to measure a wider-array of school-relevant productive writing skills through tasks like those used here.

For educators, the finding that there is much variability in students’ lexico-grammatical skills and skill in discourse-level structures for organizing text within a single grade even when assessed using short writing tasks is particularly enlightening. Despite reducing the cognitive and background knowledge demands of the task, a proportion of students in each grade either appeared to lack the linguistic resources required or the skills to recognize the need to use these academic forms (see Table 2). Given the ubiquity of short writing tasks as a mechanism to assess knowledge in upper elementary and pre-adolescent writers at school, it is possible that the linguistic demands of such tasks are frequently invisible to educators. This study demonstrates, however, that the language skills called upon to produce even short text segments that meet academic expectations are not fully developed for all students by the end of middle school. Educators should be mindful that, in addition to learning content, elementary and middle grade students are still acquiring knowledge of how best to linguistically package this knowledge for an academic audience (Snow & Uccelli, 2009).

When mindful of these challenges, educators might be better positioned to provide linguistically supportive instruction. This is not to suggest that linguistic skills, like those assessed here, be taught divorced from content or viewed as an instructional end; instead, language-conscious instruction, or instruction that supports writers to attend to a range of language choices as they learn to convey their meanings, may be viewed as an extension of content learning. Future intervention studies could explore how expanding students’ language resources while offering extensive practice in academic writing about content—where students reflect on both language and meaning—might consolidate these skills and support writing quality. As Deane (2013) and Crossley, Roscoe, and McNamara (2014) suggest, writers who possess adequate linguistic skills can divert cognitive resources to focus on sharpening their arguments and propositions. Pedagogy that focuses on argumentative and expository writing has tended to be focused on the writing process; however, this instruction might place equal attention on supporting students to develop the school-relevant language needed to convey this thinking in writing. In the context of content-focused writing goals, definitions and discourse-level structures might be particularly relevant text fragments to selectively discuss with students as key building blocks in the composition of extended texts. Intentional instruction that (a) explicitly highlights the academic language expectations of definitions and micro-genres (among others), and (b) scaffolds school-relevant language skills that support the production of these academic writing building blocks could be designed and its impact on the quality of students’ extended writing tested. In part, this instruction may be hindered by the way we assess writing in most classrooms—with little focus on the linguistic aspects of the task. Educators might consider whether holistic rubrics designed to measure writing proficiency are sufficiently sensitive to inform pedagogically-responsive instruction that attends explicitly to language. Rubrics parsing written language skills into those that support text organization of micro-genres, precision, and conciseness may support educators in measuring developing writers’ language growth and in providing targeted feedback and instruction. Because we so often teach what we can assess, the short tasks used in this study are promising for their ability to make visible a set of isolated language skills that could be highlighted in the course of authentic writing instruction.

Limitations

The sample in this study is small and drawn from one school; therefore, the findings and conclusions may not generalize to other populations. Also, the cross-sectional nature of these data limits the utility of these findings to understanding the developmental nature of these skills. Longitudinal studies that explore whether the results documented here are replicated in larger populations and in different instructional contexts are necessary. As the first study to conceptualize and operationalize these constructs in this way, the innovation of the tasks used here comes at the cost of not being able to directly compare our specific quantitative results with those from prior studies. The upward trend across grades documented in this study contributes to building a developmental model of language for academic writing; however, identifying factors that might explain this variability was beyond the scope of this study. In reference to specific tasks, because of our interest in examining students’ skills to recognize and produce certain, school-relevant micro-genres, we opted to select a pre-specified set of highly prevalent academic micro-genres to test. This limits our ability to examine the parity between students’ performances in micro-genre production across both open elicitation tasks (essays, longer writing samples) and text continuation tasks (like the paragraph continuation task used in this study).

Avenues for future research

This study points to many avenues for future research and, in particular, we hope that others will explore the relationship between lexico-grammatical skills and skill in producing micro-genres in larger samples. Certainly, future research should explore if correlations on a similar magnitude generally characterize the relationships between the language skills explored in this study across a range of writing tasks, including extended writing tasks, and if these correlations change in magnitude across development. Future studies might also examine the associations between the skills measured via these minimal tasks and skills in producing long compositions. A writer’s skills might be ideally captured through the elicitation of both longer texts of multiple genres and short writing tasks. However, the benefits and limitations of using open-ended text elicitation versus more structured short writing tasks for assessment and instruction of school-relevant language skills need to be explored. Intervention studies that design pedagogical approaches based on these findings and test how an instructional focus on these minimal writing tasks might impact students’ skill in more extended academic writing might offer a promising path for informing writing instruction. In conclusion, future studies might also explore the impact of various language experiences (amount of experience in academic settings, exposure to complex texts, participation in outside-of-school literacy activities) on the subset of language skills explored in this study that support adolescents as they learn to express their thoughts in writing in the classroom.

Notes

A horse is a four-legged + mammal + that can be ridden for + transportation.

(compact pre-modifier) + (superordinate) + (relative clause + nominalization).

In this study, English Language Learners (ELLs) refers to students who the school district have determined to face difficulty in accessing classroom instruction in English because of their levels of English proficiency.

Of note for this study, which employs a relatively small sample (n = 235), are the findings of Flora and Curran (2004), who demonstrated that WLSMV produced accurate test statistics, standard errors, and parameter estimates for medium sized models (10–15 indicators) with small samples (150–200). Therefore, we have reason to believe that the sample used in this study, which employed a particularly parsimonious model, is adequate.

Because the discourse-level structure text continuation items had patently non-normal distributions (most students received a score of 1 or 5), these items were recoded as binary variables (answers scored 1–3 = 0; answers scored as 4–5 = 1). In contrast, the definition scores showed a normal distribution and were retained as they were scored.

However, for this model, SRMR is not reported because this fit statistic does not perform well with binary indicators (Yu, 2002).

Other models also fit the data, including a single factor model as well as an alternative two-factor model that included unique dimensions for Lexico-grammatical skill’ and ‘knowledge of paragraph-level organization structures,’ but, unlike the winning model described above, specified cross-loadings between two indicators on the latter latent factor. Each of these models had important limitations. For example, a single factor model comprised of five indicators (a single testlet representing Lexico-grammatical skill and four indicators representing knowledge of discourse-level structures) was a good fit to the data {X 2(11) = 10.16, p = 0.07, RMSEA = 0.07 (90 % CI 0.00–0.125), TLI = 0.98, CFI = 0.99}. Yet, this model was not invariant across middle grade and elementary grade populations, and, as a result, would be inappropriate for comparing the performance in these two groups. Additionally, a two-factor model that specified a cross-loading between two indicator of the four indicators that comprised the latent construct ‘knowledge of paragraph-level organization structures’ was not selected as the final model despite demonstrating good fit to the data because there appears to be no sound theoretical reason for specifying this relationship between these two indicators. It is possible that construct-irrelevant features of the task—such as the similarity in format between these two items –may be at the root of this apparent shared variance. Future researchers might explore these models.

References

Abbott, R. D., & Berninger, V. W. (1993). Structural equation modeling of relationships among developmental skills and writing skills in primary-and intermediate-grade writers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(3), 478.

Abbott, R. D., Berninger, V. W., & Fayol, M. (2010). Longitudinal relationships of levels of language in writing and between writing and reading in grades 1 to 7. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(2), 281.

Bar-Ilan, L., & Berman, R. A. (2007). Developing register differentiation: The Latinate-Germanic divide in English. Linguistics, 45(1), 1–35.

Beers, S. F., & Nagy, W. E. (2009). Syntactic complexity as a predictor of adolescent writing quality: Which measures? Which genre? Reading and Writing, 22(2), 185–200.

Beers, S. F., & Nagy, W. E. (2011). Writing development in four genres from grades three to seven: Syntactic complexity and genre differentiation. Reading and Writing, 24(2), 183–202.

Benelli, B., Belacchi, C., Gini, G., & Lucangeli, D. (2006). “To define means to say what you know about things”: The development of definitional skills as metalinguistic acquisition. Journal of Child Language, 33(1), 71–97.

Berman, R. (2004). Language development across childhood and adolescence (Vol. 3). John Benjamins Publishing.

Berman, R. A., & Nir-Sagiv, B. (2007). Comparing narrative and expository text construction across adolescence: A developmental paradox. Discourse Processes, 43, 79–120.

Berman, R. A., & Ravid, D. (2009). Becoming a literate language user: Oral and written text construction across adolescence. In D. R. Olson & N. Torrance (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of literacy (pp. 92–111). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Berman, R. A., & Verhoeven, L. (2002). Cross-linguistic perspectives on the development of text-production abilities: Speech and writing. Written Language & Literacy, 5(1), 1–43.

Berninger, V. W., & Abbott, R. D. (2010). Listening comprehension, oral expression, reading comprehension, and written expression: Related yet unique language systems in grades 1, 3, 5, and 7. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(3), 635.

Berninger, V. W., Cartwright, A. C., Yates, C. M., Swanson, H. L., & Abbott, R. D. (1994). Developmental skills related to writing and reading acquisition in the intermediate grades. Reading and Writing, 6(2), 161–196.

Biber, D. (1988). Variation across speech and writing. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D., & Conrad, S. (2009). Register, genre, and style. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biemiller, A. (2010). Words worth teaching: Closing the vocabulary gap. Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill SRA.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research, 17(3), 303–316.

Bravo, M. A., & Cervetti, G. N. (2008). Teaching vocabulary through text and experience in content areas. In A. E. Farstrup & S. J. Samuels (Eds.), What research has to say about vocabulary instruction (pp. 130–149). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Britton, B. K. (1994). Understanding expository text: Building mental structure to induce insights. In M. A. Gernsbacher (Ed.), Handbook of psycholinguistics (pp. 641–674). San Diego: Academic Press.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Press.

Brysbaert, M., Warriner, A. B., & Kuperman, V. (2014). Concreteness ratings for 40 thousand generally known English word lemmas. Behavior research methods, 46(3), 904–911.

Carrow-Woolfolk, E. (1995). OWLS (oral and Written Language Scales) manual: Listening comprehension and oral expression. American Guidance Service.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155.

Coltheart, M. (1981). The MRC psycholinguistic database. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 33(4), 497–505.

Corson, D. (1997). The learning and use of academic English words. Language Learning, 47(4), 671–718.

Craswell, G., & Poore, M. (2012). Writing for academic success. London: Sage.

Crossley, S. A., Roscoe, R., & McNamara, D. S. (2014). What is successful writing? An investigation into the multiple ways writers can write successful essays. Written Communication, 31(2), 184–214.

Crossley, S. A., Weston, J. L., Sullivan, S. T. M., & McNamara, D. S. (2011). The development of writing proficiency as a function of grade level: A linguistic analysis. Written Communication, 28(3), 282–311.

Crowhurst, M. (1980). Syntactic complexity in narration and argument at three grade levels. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue canadienne de l'éducation, 5(1), 6–13.

Crowhurst, M. (1987). Cohesion in argument and narration at three grade levels. Research in the Teaching of English, 21(2), 185–201.

Deane, P. (2013). On the relation between automated essay scoring and modern views of the writing construct. Assessing Writing, 18, 7–24.

El Euch, S. (2007). Concreteness and language effects in the quality of written definitions in L1, L2 and L3. International Journal of Multilingualism, 4(3), 198–216.

Finney, S., & DiStefano, C. (2006). Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In G. R. Hancock & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (pp. 269–314). Greenwich: Information Age.

Flora, D. B., & Curran, P. J. (2004). An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychological Methods, 9(4), 466.

Geva, E., & Farnia, F. (2012). Developmental changes in the nature of language proficiency and reading fluency paint a more complex view of reading comprehension in ELL and EL1. Reading and Writing, 25(8), 1819–1845.

Gini, G., Benelli, B., & Belacchi, C. (2004). Children’s definitional skills and their relations with metalinguistic awareness and school achievement. School Psychology, 2(1–2), 239–267.

Graesser, A. C., McNamara, D. S., Louwerse, M. M., & Cai, Z. (2004). Coh-Metrix: Analysis of text on cohesion and language. Behavior Research Methods, 36(2), 193–202.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1993). Towards a language-based theory of learning. Linguistics and Education, 5(2), 93, 116.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Hasan, R. (1976). Cohesion in English. London: Longman.

Hoover, W. A., & Gough, P. B. (1990). The simple view of reading. Reading and Writing, 2(2), 127–160.

King, M., & Rentel, V. (1979). Toward a theory of early writing development. Research in the Teaching of English, 13, 243–253.

Kurland, B. F., & Snow, C. E. (1997). Longitudinal measurement of growth in definitional skill. Journal of Child Language, 24(3), 603–625.

Lesaux, N. K., & Kieffer, M. J. (2010). Exploring sources of reading comprehension difficulties among language minority learners and their classmates in early adolescence. American Educational Research Journal, 47(3), 596–632.

MacWhinney, B. (2000). The CHILDES project: Tools for analyzing talk, volume II: The database (Vol. 2). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Maguire, M., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2006). 14 A unified theory of word learning: Putting verb acquisition in context. In K. Hirsh-Pasek & R. M. Golinkoff (Eds.), Action meets word: How children learn verbs (pp. 3–28). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Marinellie, S. A. (2009). The content of children’s definitions: The oral-written distinction. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 25(1), 89–102.

Marinellie, S. A., & Johnson, C. J. (2004). Nouns and verbs: A comparison of definitional style. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 33(3), 217–235.

Martin, J. R., & Rose, D. (2007). Working with discourse: Meaning beyond the clause. London: Continuum.

McCutchen, D. (2000). Knowledge, processing, and working memory: Implications for a theory of writing. Educational psychologist, 35(1), 13–23.

McCutchen, D., & Perfetti, C. A. (1982). Coherence and connectedness in the development of discourse production. ERIC Clearinghouse.