Abstract

We examined theoretical issues concerning the development of reading fluency and language proficiency in 390 English Language Learners (ELLs,) and 149 monolingual, English-as-a-first language (EL1) students. The extent to which performance on these constructs in Grade 5 (i.e., concurrent predictors) contributes to reading comprehension in the presence of Grade 2 autoregressors was also addressed. Students were assessed on cognitive, language, word reading, and reading fluency skills in Grades 2 and 5. In Grade 2, regardless of language group, word and text reading fluency formed a single factor, but by Grade 5 word and text reading fluency formed two distinct factors, the latter being more aligned with language comprehension. In both groups a substantial proportion of the variance in Grade 5 reading comprehension was accounted for uniquely by Grade 2 phonological awareness and vocabulary. Grade 5 text reading fluency contributed uniquely in the presence of the autoregressors. By Grade 5 syntactic skills and listening comprehension emerged as additional language proficiency components predicting reading comprehension in ELL but not in EL1. Results suggest that predictors of reading comprehension are similar but not identical in ELL and EL1. The findings point to a more nuanced and dynamic framework for understanding the building blocks that contribute to reading comprehension in ELLs and EL1s in upper elementary school. They underscore the importance of considering constructs such as vocabulary, whose role is stable, and other components of language proficiency and reading fluency whose role becomes pivotal as their nature changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The available research on reading skills of second language (L2) learners has shown that L2 status and under-developed language skills do not exert their influence uniformly across different reading components. In particular, studies show rather consistently, that L2 students perform more poorly on reading comprehension tasks and have less well-developed oral language skills than their monolingual counterparts (e.g., Aarts & Verhoeven, 1999; Carlisle, Beeman, Davis, & Spharim, 1999; Hutchinson, Whiteley, Smith, & Connors, 2003; Nakamoto, Manis, & Lindsey, 2007). A handful of studies have also shown that L2 learners may read texts with less fluency than their monolingual counterparts (e.g., Crosson & Lesaux, 2010), and that they may read with less fluency in their L2 than in their first language (L1) (e.g., Geva, Wade-Wooley, & Shany, 1997). However, there is research evidence that L2 status, and in particular, underdeveloped L2 skills do not compromise seriously the performance of English language learners (ELLs) on underlying cognitive skills such as phonological awareness, naming speed, verbal working memory, and on word based reading skills such as accurate and fluent word-level reading skills (for a review see Geva, 2006; see also Lesaux & Siegel, 2003).

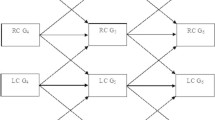

In recent years researchers have begun to examine from a developmental perspective reading fluency and other cognitive processes that may play a significant role in the reading comprehension of ELLs and English as a first language (EL1) students. In the research reported here we first examined the construct of reading fluency in ELLs and EL1s, and the extent to which its nature changes at two time points. The simple view of reading (SVR) framework (Hoover & Gough, 1990) has guided some of the research on reading comprehension of first language (L1) and L2 learners. This framework suggests that variables associated with language comprehension and with word-level reading skills are the two main “pillars” that underlie reading comprehension. More recently researchers have pointed out that the SVR needs to be supplemented with factors such as working memory, reading fluency, and strategic knowledge (e.g., Cain, Oakhill,& Bryant, 2004; Joshi & Aaron, 2000; kirby & Savage, 2008; Lesaux, Rupp, & Siegel, 2007).

In this study, we examined a variant of the SVR framework that includes word-level reading skills, and three distinct aspects of oral language comprehension (i.e., vocabulary, syntax, and listening comprehension). The model was further augmented with cognitive skills and word and text reading fluency. In essence, we examined whether skills that have been shown to be related to reading comprehension continue to exert their influence at a later time, or whether the nature of what predicts reading comprehension changes as a result of developmental changes in what reading comprehension or the predictors themselves entail.

Oral language skills and development in word and text reading fluency

Reading fluency has been often assessed with accuracy and speed of reading isolated words, connected texts, or a combination of both (e.g., Biemiller, 1981; Crosson & Lesaux, 2010; Jenkins, Fuchs, van den Broek, Espin, & Deno, 2003; Meyer & Felton, 1999). Wolf and Katzir-Cohen (2001) suggested that the nature of the construct of reading fluency changes with development; in the early stages of reading acquisition, reading fluency involves a gradual development of accurate and automatic execution of word-level reading skills, including the ability to process large orthographic units, phonological, lexical, and morphological processes. They suggested that once readers have developed fluency with these basic word-level aspects of reading, and word decoding becomes effortless and fast, more attentional resources can be allocated to higher level reading skills, including text reading fluency and text comprehension. This literature suggests that it may be productive to consider word fluency and text reading fluency as distinct constructs.

There is general agreement that while fluent reading of isolated words may be less dependent on higher level language skills, fluent reading of connected text is more closely linked to language skills (Wolf & Katzir-Cohen, 2001). It is also generally agreed that language skills, including vocabulary, syntactic knowledge, and comprehension of spoken language are essential for text reading fluency (e.g., Biemiller, 1981; Cohen-Mimran, 2009; Cutting, Materek, Cole, Levine, & Mahone, 2009; Meyer & Felton, 1999; Perfetti, 2007; Puranik, Petscher, Al Otaiba, Catts, & Lonigan, 2008; Torgesen, Rashotte, & Alexander, 2001). For example, as demonstrated three decades ago by Biemiller (1981) monolingual school children take less time to read the same words in context than out of context. These findings illustrate the fact that when reading connected texts readers can benefit from linguistic knowledge, but such contextual facilitation is unavailable when reading isolated words.

Support for the fact that language skills are essential for text reading fluency comes also from a small number of studies involving Spanish speaking ELLs (e.g., Al Otaiba, Petscher, Pappamihiel, Williams, Drylund, & Connor 2009; Crosson & Lesaux, 2010; Nakamoto, Lindsey, & Manis, 2007), and studies involving L2 from different language backgrounds (Geva, et al., 1997; Geva & Yaghoub Zadeh, 2006). L2-based studies suggest that a positive relationship between text reading fluency and language skills can be observed only when a certain threshold of language proficiency has been attained. The study by Geva, et al. (1997) involving reading in L1 and L2 illustrates the importance of linguistic skills and the notion of a language proficiency threshold. This study involved grade 1 and grade 2 children with English as the home language, who were enrolled in a bilingual English-Hebrew program. Children read with the same level of speed and accuracy isolated words in English and Hebrew. At the same time, their performance on text reading fluency was superior in their L1 (English) whereas it was very poor in their L2, due to their underdeveloped Hebrew language skills. Relatedly, in grade 1 when children’s Hebrew proficiency was minimal Hebrew listening comprehension did not predict text reading fluency. Instead, it was predicted by fluent Hebrew word reading skills. However, in grade 2, as their Hebrew language skills became stronger, listening comprehension became a significant predictor of text reading fluency. The study by Crosson and Lesaux (2010) provides additional support for the notion of some kind of a linguistic threshold below which linguistic knowledge is not sufficient to support the language demands of text processing.

Very little is known about the extent to which ELLs with different levels of L2 proficiency can capitalize on their linguistic proficiency and read texts with more fluency than isolated words. In the present study we compared the speed of reading isolated words and words in connected text, and addressed the threshold notion by examining the correlations between language proficiency components and word and text reading fluency in Grade 2 and again when students were in Grade 5. We hypothesized that the correlations between oral language proficiency components and text reading fluency would be more robust in Grade 5 than in Grade 2 in both language groups.

Predictors of reading comprehension in ELL and EL1

In recent years, researchers have adopted a more dynamic, developmental approach to the study of reading fluency and its relationship with reading comprehension (e.g. Berninger, et al., 2010; Kame’enui, Simmons, Good, & Harn, 2000; Collins & Levy, 2008; Wolf & Katzir-Cohen, 2001). For example, Meyer and Felton (1999) defined reading fluency as “the ability to read connected text rapidly, smoothly, effortlessly, and automatically with little conscious attention to the mechanics of reading such as decoding” (p. 284). Others emphasize in their conceptualization of reading fluency the efficient processing of meaning (Carver, 1997; Perfetti, 1985; Schreiber; 1980; for a review see the National Reading Panel, 2000, and a special issue edited by Wolf and Katzir-Cohen 2001). In general, there is agreement in the research literature that fluent reading requires simultaneous attention to accurate and effortless decoding and to language comprehension (Hoover & Gough, 1990; Samuels, 2002; Samuels, Schermer, & Reinking, 1992).

Word reading fluency might be a better early predictor of reading comprehension and text reading fluency may be a better later predictor of reading comprehension. Research evidence from L1-based studies does not yield however a clear conclusion. For example, in a study involving grade 4 monolingual students, Jenkins et al. (2003) investigated whether reading comprehension shares more variance with isolated word reading fluency or with text reading fluency. They found that text reading fluency accounted for a significant amount of variance in reading comprehension, whereas isolated word fluency explained only 1% unique variance. However, in a cross-sectional study of grades 2, 4, and 8 monolingual students, Adlof, Catts, and Little, (2006) report somewhat different results. Adlof, et al. (2006) examined the association between text reading fluency and reading comprehension, and found that text reading fluency did not add any unique variance to reading comprehension, once accuracy in word-level reading skills and oral language skills have been taken into account. The discrepancy in the conclusions may reflect methodological differences between the studies. Jenkins et al. (2003) did not include cognitive or oral language measures in their study, and in the Adlof, et al. (2006) study there was a large percentage of participants with language impairment, and the age range of the participants was much larger.

Even though less is known about the relationship between reading fluency and reading comprehension in L2 learners, the available research points to the significant role that word and text reading fluency play in reading comprehension. For example, a recent study by Crosson and Lesaux (2010), that involved grade 5 ELLs from a Spanish speaking background, demonstrated that over and above the contribution of word reading fluency and oral language proficiency, text reading fluency was a unique predictor of reading comprehension. Interestingly, text reading fluency predicted reading comprehension only for a sub-group of ELLs whose oral language skills were already better developed. This result supports the notion that the nature of the reading fluency construct changes over time. Wiley and Deno (2005) who examined the relationship between text reading fluency and reading comprehension in grade 3 and 5 ELLs and EL1s, found a stronger relationship between text reading fluency and reading comprehension in EL1s than in ELLs. Also of relevance to the current study was the finding that text reading fluency and reading comprehension were more strongly correlated among the fifth grade than the third grade ELLs. Taken together, these results suggest that younger and less proficient L2s have less developed language skills than their monolingual or more proficient counterparts, and may therefore focus primarily on fluent decoding even when they read connected texts. With better developed language skills, older or more proficient L2 learners may be able to capitalize on the processing of meaning as well (Crosson & Lesaux, 2010; Geva & Yaghoub Zadeh, 2006; Wiley & Deno, 2005).

The present study

The present study was designed to add to the literature on the relationship between reading fluency and reading comprehension in monolingual and ELLs in two complementary ways. First we examined the extent to which the nature of the construct of reading fluency changes between Grades 2 and 5. As noted earlier, ample research evidence suggests that oral language skills are essential for text reading fluency. It also suggests that the role of oral language proficiency in reading fluency changes over time. For example, Chall, Jacobs, and Baldwin, (1990) pointed out that typically in the primary grades, while students acquire accurate and fluent decoding skills, the language demands of reading materials are not challenging. In subsequent years, concomitant with a gradual “ungluing from print” and the requirement to “read in order to learn”, the language of texts becomes more demanding. Therefore, we hypothesized that for ELL and EL1 students, word and text reading fluency would be less differentiated in Grade 2 than in upper elementary grades, and that the degree of association between reading comprehension and word and texts reading fluency would vary as a result of this developmental shift in the construct of reading fluency.

Second, the study examined whether a more complex variant of SVR that includes not only aspects of oral language and word-level reading skills, but also word and text reading fluency, and cognitive processing skills (i.e., working memory, naming speed, and phonological awareness), would result in a more comprehensive model of reading comprehension in ELLs and EL1s.

An interesting question that has not been addressed so far is the extent to which skills that have been shown to be related to reading comprehension continue to exert their influence at a later time, and whether the nature of what predicts reading comprehension changes as a result of changes in what constitutes reading comprehension and/or changes in the nature of the predictors themselves (e.g., Catts, Fey, Zhang, & Tomblin, 1999; Cutting & Scarborough, 2006; Francis et al., 2005; Gottardo & Mueller, 2009; Storch & Whitehurst, 2002; Whitehurst & Lonigan, 1998). The general argument made in these studies has been that in upper elementary grades, as word-level reading skills become better established, factors such as language skills and world knowledge become more prominent predictors of reading comprehension. Furthermore, a shift occurs from heavy reliance on word-level reading skills as a primary component of reading comprehension to reading comprehension that is multidimensional and complex and that requires the integration of various components including (but not limited to) aspects of language skills, text reading fluency, background knowledge, strategic knowledge, and working memory. Given this literature we hypothesized that skills that have been shown to be related to reading comprehension in Grade 2 would continue to exert their influence three years later, over and above the Grade 2 autoregressors. Furthermore we hypothesized that in upper elementary grades more complex aspects of oral language (such as syntactic knowledge and listening comprehension), and text reading fluency would play a more substantial role in reading comprehension than skills whose role had been dominant in the primary grades.

Method

Demographic background

The data forming the basis of this study were part of a multiple cohort, cross-sequential, longitudinal design. Waves of data were collected every year for four consecutive years. The study involved 35 classrooms in 14 schools in four different boards of education in a large multiethnic and multilingual metropolis in Ontario, Canada. It is important to note that the ELL and EL1 students came from the same schools and were drawn from the same classes. Individual level demographic data were not accessible but we had access to relevant census data concerning the neighborhoods in which the participating schools were situated (Statistics Canada, 2001). The Canadian Census provides access to demographic data at the postal code level. According to the 2001 Canadian Census, about 58% of the families living in the neighborhoods in which the participating schools are located reported a language other than English or French (the two Canadian official languages) as the home language. About 91% of the families were first-generation immigrants, and 68% of the parents immigrated when they were at least 20 years old. According to 2001 Canadian Census data, the median family income in the 12 communities feeding into the participating schools was substantially lower than the median income reported for the metropolis. There was substantial variation in the level of education of the adults living in these neighborhoods: 36% of the individuals living in the relevant postal code blocks had not obtained a high school diploma or did not finish high school, 13% had a high school diploma, 27% had either a trade certificate or college education, and 20% had obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher. These statistics are typical of Canadian immigrant distributions and reflect Canadian immigration policies.

In Ontario, ELLs from different home language backgrounds attend the same schools, and the language of instruction is English. Recent immigrants from non-English speaking countries or with limited English proficiency are typically placed in regular classrooms. They are withdrawn from these classrooms on a daily basis for 30–40 min sessions of English language instruction, provided by teachers with English as a second language (ESL) specialist training. The ESL classes are offered to a mix of students of various ages and home language backgrounds. Students are grouped on the basis of level of English language proficiency. They are entitled to receive this intensive ESL support up to 2 years. Other than these ESL classes, students are integrated into the regular classroom, and the regular classroom teachers are expected to make the necessary instructional accommodations.

Participants

The longitudinal study was launched in 1996 and involved 611 participants. The following criteria were used to exclude participants from subsequent analyses: (a) students with non-verbal ability standard scores equal to or smaller than 80 (n ELL = 7; n EL1 = 5); (b) students whose decoding score was 2.5 standard deviations below their respective ELL or EL1 group means (n ELL = 9; n EL1 = 4), (c) ELLs who had had more than two years of schooling/daycare in English prior to Grade 1 (n = 20); and (d) students who spoke nonstandard, Caribbean English (n = 27).

The final data included information from 539 ELL and EL1 students. The ELL sample consisted of 390 students who spoke at home a language other than English: Punjabi (n = 131), Gujarati (n = 54), Tamil (n = 50), Cantonese (n = 50), Portuguese (n = 86), or other languages (n = 19). The EL1 sample included 149 monolingual English-speaking students. Information on the language status of the ELLs was extracted from each student’s Ontario School Record. It was then verified by teachers and triangulated with information provided by parents and their children through interviews. These interviews also confirmed that the participants used their home language on a daily basis outside school. Mean age of the ELL group in Grade 5 was 10 years and 6 months (SD = 3.33 months), and the mean age of the EL1 group was 10 years and 8 months (SD = 3.8 months). There were 199 girls and 191 boys in the ELL group, and 89 girls and 60 boys in the EL1 group. Eighty-one percent of the ELLs for whom data on the country of birth were available (n = 239) were born in Canada, but spoke a language other than English at home.

Attrition is unavoidable in longitudinal research. The attrition rate was moderate and ranged between 22% to 27% per year, reducing the number of participants from 539 in Grade 2 to 257 in Grade 5. School records indicated that mobility was a common reason for data attrition. To ensure the randomness of attrition and incomplete data we conducted a sensitivity analysis (Schulz, Chalmers, Hayes, & Altman, 1995). The results are reported under ‘Handling missing data’ in the Results section.

Independent variables

Non-verbal ability

The Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices (Raven, Court, & Raven, 1983) was administered to assess students’ non-verbal ability. Children were shown an incomplete illustration of a matrix and asked to select the correct pattern from a set of 5 or 6 that would complete the matrix. This test was administered in Grade 5 only as a general cognitive control measure.

Working memory

The backward digit span subtest of WISC-III Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Third Edition (Wechsler, 1991), was used to measure working memory. The task assesses intake, maintenance, processing, and retrieval of information. Children are required to recall, in a reverse order, a series of orally presented digits that increase in set size. Administration was interrupted when both sets in the same trial were wrong. The test–retest reliability coefficientsFootnote 1 of this task were .41 and .26, for ELL and EL1 students, respectively. This test was administered in Grades 2 and 5.

Phonological processing

Two aspects of phonological processing were assessed: phonological awareness and naming speed. These tests were administered in Grade 2 and 5.

Naming speed

The letter naming section of Denckla and Rudel’s (1976) Rapid Automatization Naming Test (RAN) was used. It includes 5 letters, each appearing 10 times in a random order. Accuracy and time (in seconds) to name all 50 items are recorded. The speed of naming metric was the number of correct letters named per second.

Phonological awareness

An adapted version of the Auditory Analysis Test (Rosner & Simon, 1971)Footnote 2 was used to measure phonological awareness. In order to minimize the effect of lexical knowledge and an EL1 advantage, only high frequency words were used for the initial stimuli and target responses in this task (e.g., sunshine, picnic, leg). The task consists of 25 items forming 3 sets of progressive difficulty. In the first set the students were asked to delete one syllable in either initial or final position of a spoken word (e.g. “Say sunshine”; “Say it again but don’t say shine”). The second set required deletion of initial or final single phonemes in one-syllable words (e.g., “Say hand”; “Say it again but don’t say the /h/”). The third subtest involved deletion of single phonemes in an initial or final consonant blend (e.g., “Say stop”; “Say it again without /s/”). The internal consistency for this test was .92 and .89 for ELL and EL1, respectively.

Oral language measures

Three components of English language proficiency, varying in unit size, were assessed in Grade 2 and 5: vocabulary, syntactic knowledge, and listening comprehension. When the project was launched the school boards did not permit the use of standardized measures of higher order language (i.e., syntactic skills, listening comprehension) to assess ELLs, since these tasks were normed on EL1. Therefore, in Grade 2 experimental measures were used to assess syntactic skills and listening comprehension. As their language skills improved the ELLs’ performance on the measures used in Grade 2 reached ceiling and we were subsequently allowed to use standardized measures to assess syntactic skills and listening comprehension.

Receptive vocabulary

The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised (PPVT-R) (Dunn & Dunn, 1981) was used to measure students’ receptive vocabulary in Grades 2 and 5. On this standardized task students hear a spoken word and are shown four pictures. They are asked to point to the picture that matches the word they have heard. The PPVT has been shown to be a good measure of oral language proficiency. Raw scores were used in this study since the PPVT was not standardized for ELLs.

Syntactic skills

In Grade 2, an adapted and abbreviated version of the Grammaticality Judgment Task (Johnson & Newport, 1989) was used to test participants’ English syntactic knowledge. The task consists of 40 sentences: 20 syntactically correct (e.g., “The man burned the dinner.”) and 20 syntactically incorrect (e.g., “Last night the books falled off the shelves.”). The task tests a wide variety of English syntactic properties. Only relatively high frequency words were used and the sentences were constructed with items whose intended meaning was transparent, in order to control for semantic knowledge and to reduce possible effects of lexical familiarity and ELL status on students’ performance. Each sentence was played twice on a tape-recorder. The students’ task was to indicate whether the sentence they had heard was said “the right way” or “the wrong way.” The total score reflected the number of correctly judged sentences. The internal consistency of the task was .77 and .80 for ELLs and EL1s, respectively.

In Grade 5 the Formulated Sentences subtest of the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals—Third Edition (CELF-3; Semel, Wigg & Secord, 1995) was used to assess students’ syntactic skills. This 22 item test requires children to generate sentences based on a picture, using a target word or phrase provided by the tester for each item. Sentences are scored from 0 to 2, on the basis of appropriate reference and grammatical correctness. The internal consistency of the task was .81 and .71 for ELLs and EL1s, respectively.

Listening comprehension

In Grade 2, the listening comprehension (LC) task was adapted from the Durrell Analysis of Reading Difficulty (Durrell, 1970). This measure comprises two short stories (about a paragraph in length) that represent different difficulty levels. There are eight idea units in each story. Each story was read to the child, and the child was instructed to listen to the stories carefully as they would be asked to retell the story and answer some questions about it. After listening to each story, the child was asked to retell the story and then answered 1 inferential and 4 factual multiple choice questions, presented orally by the tester. The maximum score on each story was 13, and the total score was 26.

Children’s story retelling and answers were tape-recorded on an audiotape. The recordings were later transcribed and scored by two native English speaking raters. For the free recall component, children were given one point for each idea unit recalled. One point was also given for each correctly answered oral comprehension question. Children were not penalized for making grammatical errors in the free recall or the question–answer components of this task. The internal consistency of the task was .73 and .47 for ELLs and EL1s, respectively. The low reliability in the EL1 group is due to a ceiling effect. On individual items the inter-rater reliability between the two raters was greater than 85%.

In Grade 5, the Listening to Paragraphs subtest of the CELF-3 (Semel, Wigg & Secord, 1995) was used to assess students’ listening comprehension. Students are required to listen to two age appropriate short paragraphs from the test, followed by 5 questions regarding those paragraphs. The paragraphs target listening comprehension at the factual and inferential levels. The total number of correct responses to questions (out of 10) formed the child’s score. The internal consistency of the task was .76 for ELLs and EL1s, alike.

Reading measures

Word level skills in Grade 2 and 5 were assessed with standardized measures. Word and text reading fluency in Grade 2 and 5 were assessed with experimental measures.

Pseudoword decoding

The Word Attack subtest of the Woodcock Reading Mastery Test-Revised (Woodcock, 1987) was administered to assess students’ ability to apply grapheme-phoneme correspondence rules in decoding pseudowords. The test consists of 45 pronounceable “nonwords” that conform with the rules of English orthography (e.g., bufty, mancingful). The total of correctly read items was considered each child’s total score. This task was used to identify poor decoders in Grade 5. Specifically, data of students who scored 2.5 standard deviation below the mean of their respective language group on this task in Grade 5, were removed from subsequent analyses. The internal consistency of the task was .87 and .91 for ELLS and EL1s, respectively. Since this task was used as a screening measure of reading disabilities, it was not used in other analyses.

Word identification

The word reading subtest of the Wide Range Achievement Test-Revised (WRAT 3-R; Wilkinson, 1993) was administered to assess students’ ability to read isolated words in English. This test consists of 42 monosyllabic and polysyllabic words. The items involve nouns, verbs, adjectives, and prepositions. The test was discontinued after 10 consecutive errors. The total number of correctly read words was considered as each child’s score. The internal consistency of the task was .91 and .94 for ELLs and EL1s, respectively.

Word and text reading fluency

In Grade 2 and 5 reading fluency was assessed with experimental measures. Two aspects of oral reading fluency were measured—isolated words and words in connected texts. Different oral word and texts fluency measures were used in Grades 2 and 5.

In Grade 2, the Biemiller Test of Reading Processes (Biemiller, 1981) was used to measure word and text reading fluency. The test yields measures of accuracy and speed for reading isolated words and narrative texts. The isolated word lists came from the corresponding 2 narratives texts. Biemiller (1981) pointed out that the goal of the test is not to ascertain word reading accuracy but the speed at which students read these words, so the words were chosen because they could be decoded with minimal difficulty. A parallel measure was developed for Grade 5.

Text fluency

In Grade 2 children were presented with two, 100-word, narrative texts. The instructions prior to each story were as follows: “I want you to read this story. Remember to go as fast as you can, and do not worry about making mistakes. You may not know all the words but I want you to try your best.” The first narrative, entitled “Bear” includes words such as, bear, thank, fish, tried, and father, and according to Biemiller (1981) is at the primer level. The second story, entitled “John” includes words such as register, asked, interested, things, tourists, and also, and according to Biemiller (1981) consists of words that are typical of middle elementary level reading. The Flesh-Kincaid grade level readability score analyzes and rates texts on the US grade-school level, based on the average number of syllables per word and words per sentence. We ran the two stories through the Flesh-Kincaid grade level readability analysis. The analysis confirmed that the first narrative has a score equivalent to grade 1.23, and the second narrative has a score equivalent to grade 3.30.

Word fluency

In Grade 2 children were presented with 2 isolated word lists, each consisting of 50, randomly ordered, single-morpheme words, taken from the 2 corresponding 100-word, narratives described above. The instructions were: “I want you to read some words. These words are from the story you just read, but this time they do not make a story. Remember to go as fast as you can, and do not worry about making mistakes”.

In Grade 5, based on the Biemiller Reading Fluency, we developed a measure that would be appropriate for Grade 5. For this purpose we used a grade 5-level expository text consisting of 97 words, entitled “Land Snails”, and a grade 5-level narrative text consisting of 100 words, entitled “Balloon”. The two corresponding, 50-item word lists were randomly selected from these two texts. Examples of words in the Land Snails text include: red snails, condition, slime, dryness, and protect. Examples of words in the Balloon text include: strips, cloth, attached, underneath, and anchor. The Flesh-Kincaid grade level readability analysis confirmed that the narrative text has a score equivalent to grade 5.56, and the grade equivalent score of the expository text is 5.22.

Reading fluency scores

To obtain a fluency score in the isolated words condition, we divided the total number of words read correctly on each of the two, Grade 2 word lists by the total number of seconds that a participant took to read each list. The same procedure was repeated to calculate the text fluency scores for each Grade 2 narrative. These procedures were also used to obtain fluency scores for the two isolated word lists and the Grade 5 narrative and expository texts.

Test administration

In both Grade 2 and Grade 5 the administration procedures were identical. Following the reading of each text the child read the corresponding word list. Assessment of reading fluency can be compromised if children make too many errors. Therefore, testers were instructed to aid the child who stumbled on a word by providing without delay the unknown word as well as the subsequent two words. Testers noted errors and the time, in seconds, each participant took to read each text or corresponding word list. Test–retest reliability coefficients for the word reading fluency for the ELLs and EL1s were .65 and .60, respectively. Test–retest reliability coefficients for the text reading fluency for the ELLs and EL1s were .67 and .62, respectively.

Dependent variable

Reading comprehension

The Gates-MacGinitie Reading Test (GMRT) (MacGinitie & MacGinitie, 1992) Level D5/6 Form 3 for Grade 5 was used to measure reading comprehension in Grade 5. The GMRT contains short narrative, information, and expository passages, each of which is followed by multiple-choice questions. The test, which has a time limit of 35 min, was administered in groups of five. The percent of correct responses was used as the metric in subsequent analyses.

Procedures

This project tracked language and literacy skills of EL1 and ELL students from grade 1 to grade 6. In this study, we focus on a subset of data collected in the fall of Grade 2 and winter of Grade 5. Cognitive, language, word-level reading, and reading fluency measures were assessed in Grade 2 and again in Grade 5. The Grade 2 measures were treated as early predictors (autoregressors) of Grade 5 reading comprehension. Parallel Grade 5 language, word-level reading, reading fluency, and cognitive measures were treated as concurrent predictors of Grade 5 reading comprehension. Unless specified otherwise, in this study raw scores rather than standard scores were used for standardized measures since the tests were not normed for ELLs. For this reason age in months was used as a covariate. Depending on the tasks, the participants were tested individually or in small groups. Testing was done by fully trained, experienced graduate students and research assistants. ELLs had sufficient knowledge of the English language to understand the task instructions, which were given in English.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Handling missing data

To ensure the randomness of attrition and incomplete data we conducted a sensitivity analysis (Schulz et al., 1995), in which we examined the effects of missingness on Grade 2 reading comprehension after the effects of language status (i.e., ELL vs. EL1), non-verbal ability, and gender were accounted for. No statistically significant differences were found between the reading comprehension outcomes of students who dropped out and those who remained in the study, t(612) = .34, p = .734. There were no statistically significant differences in the interaction between language status, gender, non-verbal ability, and reading comprehension of the students who dropped out and those who remained in the study, t(608) = .31, p = .760. Subsequently, we used Schafer’s (2000) NORM program to multiply impute the missing data resulted from attrition or missing data cells (Little & Rubin, 2002; Schafer & Graham, 2002). The data were imputed based on the observed Grade 1 to Grade 6 original dataset that involved 611 participants. The procedure resulted in inclusion of a substantial proportion (72%) of the data in the final analyses that would have been deleted list-wise, otherwise.

Descriptive analyses

Means and standard deviations associated with the ELL and EL1 Grade 2 and Grade 5 measures are reported in Table 1, which also includes F-values associated with ELL–EL1 comparisons on each of the measures. Contrary to what might be expected, in Grades 2 and 5 ELL students had significantly faster naming speed than their EL1 counterparts. On the other hand, as expected, on all three oral language proficiency components in both grade levels the means in the EL1 group were significantly higher than in the ELL group. It should be noted that on the non-verbal ability task (Raven’s Progressive Matrices) the mean percentile scores in the ELL and EL1 groups were in the normal range (50 and 53, respectively). On word reading the ELL and EL1 groups performed within the normal range. However, ELLs performed 2–3 years below age norms on the standardized language measures and 1 year below grade norms on reading comprehension measures. EL1s performed 2–3 years below age norms on the standardized measure of syntax. In preliminary analyses age in months was entered as a covariate. However, it was not significant in any of the analyses and therefore was not included in the results reported here.

The inter-correlations among Grade 2 predictors and their respective correlations with reading comprehension in Grade 5 are presented in Table 2. The inter-correlations among Grade 5 predictors and their respective correlations with reading comprehension in Grade 5 are presented in Table 3. In both tables correlations for the EL1 appear in the upper triangle and for the ELL in the lower triangle. A number of general observations can be made on the basis of Tables 2 and 3. In general, it is noteworthy that the correlations were rather similar in the ELL and EL1 samples. The exception was the correlation between naming speed and reading comprehension: it was significant in the case of the ELLs but not in the case of the EL1s. In both groups, accurate word reading skills and word and text fluency skills correlated positively and significantly with reading comprehension, as did oral language skills.

Exploring the nature of word and text reading fluency

To explore the nature of reading fluency in Grades 2 and 5, and establish what component skills form the construct of reading fluency in ELL and EL1, discriminant factor analyses with varimax rotation were conducted to determine the clustering of measures into groups of theoretically determined factors. The analyses were based on word and text reading fluency data in each grade level within each language group. The analysis indicated that the Grade 2 word reading fluency and text reading fluency measures loaded highly on one factor in ELL and EL1 alike. For ELLs, the reading fluency factor had an eigenvalue of 1.91 and explained 95.60% of the variance. This factor consisted of isolated word reading fluency (loading = .98) and connected text reading fluency (loading = .98). For EL1s, the factor had an eigenvalue of 1.90 and explained 94.93% of the variance. Again, this factor consisted of isolated word reading fluency (loading = .97) and connected text reading fluency (loading = .97).

The analysis of the Grade 5 narrative and expository word and text reading fluency data yielded two separate factors. One factor captured isolated word reading fluency, and the second factor captured connected text reading fluency. For ELLs, the isolated word reading fluency factor had an eigenvalue of 1.89 and explained 47.21% of the variance. This factor consisted of the word lists generated from both the narrative text (loading = .80) and the expository text (loading = .79). The connected text reading fluency factor had an eigenvalue of 1.87 and explained 94.13% of the variance. This factor consisted of the narrative text reading fluency (loading = .81) and the expository text reading fluency (loading = .79). For EL1s, the isolated word reading fluency factor had an eigenvalue of 1.86 and explained 46.57% of the variance. This factor consisted of the word list generated from the narrative text (loading = .80) and the expository text (loading = .79). The text reading fluency factor had an eigenvalue of 1.84 and explained 92.55% of the variance. This factor consisted of the narrative text reading fluency (loading = .81) and the expository text reading fluency (loading = .79). In sum, the discriminant analyses confirmed that (a) reading fluency in Grades 2 and 5 are different constructs, (b) in Grade 2 word and text reading fluency form one factor, and (c) in Grade 5 there are two factors, one involving word reading fluency and one involving text reading fluency. These conclusions were equally applicable to the ELL and EL1 samples.

An examination of the patterns of correlations helps to better understand this source of divergence in constructs. As can be seen in Table 2, in Grade 2 word identification skills were closely associated with both word and text reading fluency. However, by Grade 5 the magnitude of the correlations between accurate word identification and word and text fluency dropped significantly in both language groups. In the case of the ELLs, a Fisher-Z comparing parallel correlations in Grades 2 and 5, indicated a significant drop in the magnitude of the correlations between word identification and word reading fluency, Z(390) = 5.97, p < .001, and text reading fluency, Z(390) = 4.78, p < .001. Likewise, in the case of the EL1s, the Fisher-Z comparing parallel correlations in Grades 2 and 5, indicated a significant drop in the magnitude of the correlation between accurate word identification and word reading fluency, Z(139) = 4.99, p < .001, and text fluency, Z(139) = 3.41, p < .001.

At the same time, while the magnitude of the correlations between accurate word identification and word and text reading fluency dropped from Grade 2 to Grade 5, the magnitude of the correlations between the text reading fluency and the oral language measures increased. In the case of the ELLs, the Fisher-Z comparison indicated a significant increase from Grade 2 to Grade 5 in the magnitude of the correlations between text reading fluency and vocabulary, Z(390) = −3.03, p = .002, and syntax, Z(390) = −2.87, p = .004. In the same vein, in the case of the EL1s the Fisher-Z comparison indicated a significant increase from Grade 2 to Grade 5 in the magnitude of the correlation between text reading fluency and vocabulary, Z(139) = −2.47, p = .01, and syntax, Z(139) = −1.96, p = .05. In both language groups there were no significant changes in the magnitude of the correlations between text fluency and listening comprehension. With one exception, involving the correlation between listening comprehension and word fluency in the ELL group, Z(390) = 2.18, p = .05, the magnitude of the correlations between language measures and word reading fluency did not change from Grade 2 to Grade 5.

As an additional step in exploring the nature of word and text reading fluency in Grades 2 and 5 we examined whether ELL and EL1 children read with similar fluency isolated words, and the same words embedded in connected text. As can be seen in Table 1, there were no group differences on the number of items read per second. A two-way ANOVA was conducted separately in Grade 2 and Grade 5, with task (isolated words vs. words in connected text) and language group as the two independent variables. In Grade 2, there was a significant main task effect, with isolated words being read faster than words in text, F(1, 537) = 159.21, p < .001. There was no interaction of task by group, F(1, 537) = 2.13, p = .15. A two-way ANOVA confirmed that in Grade 5 there was a significant task effect with words in text being read faster than isolated words, F(1, 537) = 136.46, p < .001. In Grade 5, there was also a significant interaction of language group by task, with the ELLs reading isolated words faster than the EL1s, but no ELL–EL1 difference on text fluency, F(1, 537) = 5.40, p = .02. In sum, EL1 and ELL students in Grade 5 read faster words in connected text than in isolation.

Grade 2 and Grade 5 predictors of reading comprehension in ELL and EL1

We now turn to an examination of Grade 2 and Grade 5 predictors of Grade 5 reading comprehension. The following general principles guided the order in which the Grade 2 and concurrent Grade 5 variables were entered into a hierarchical multiple regression analysis with reading comprehension in Grade 5 as the dependent variable. SVR-related research has established that word-level reading skills and language components predict reading comprehension. For this reason these two clusters of variables were considered first in our regression model. As we hypothesized that word and text reading fluency would contribute to reading comprehension over and above word-level skills and language components, word and text reading fluency were considered next. The last set of variables to be considered as potential predictors involved cognitive and phonological processing measures, as we hypothesized that these processes would make additional contributions to reading comprehension after controlling for Grade 2 autoregressors.

To set the stage for this analysis it was useful to examine the correlations between parallel Grade 2 and Grade 5 predictors. Table 4 provides a summary of the correlations between early and later administration of the same constructs. It is notable that in both ELL and EL1 all the correlations are positive and significant, and they range from low-moderate to high-moderate. In particular, note that the correlations of the cognitive and phonological processes tend to be in the low-moderate range, and most of the correlations involving early and later administration of components of English language proficiency, word reading, and reading fluency tend to be somewhat higher. Note that these general observations apply also in the case where different measures of the same construct were used in Grades 2 and 5.

Results indicated that the nature of the reading fluency construct was not identical in the early years of schooling and in upper elementary grades. The finding that word and text reading fluency loaded on two different factors in Grade 5 but on one factor in Grade 2 may suggest that Grade 5 but not Grade 2 word and text reading fluency would contribute independent of each other to Grade 5 reading comprehension. In order to examine this hypothesis it was important to estimate the unique contribution of the Grade 5 word and text reading fluency to Grade 5 reading comprehension in the presence of the Grade 2 parallel fluency measures. Likewise, in order to examine whether other Grade 5 predictors (i.e., SVR components and cognitive and phonological processing skills) contribute over and above the same constructs in Grade 2 (i.e., autoregressors), we first entered into the prediction model the Grade 2 block in the order described above. We then entered hierarchically the Grade 5 parallel predictors. Hierarchical multiple regressions analyses were run separately for the ELL and EL1 groups.

The results indicated that despite their positive and significant correlations with reading comprehension, the beta weights of Grade 5 working memory, phonological awareness and word reading fluency were significant and negative. These results suggested that rather than contributing variance to reading comprehension, these three variables suppressed the error variances associated with other independent variables included in the model (e.g., word reading and text reading fluency). This often happens when there is a stronger association between the suppressor variable(s) and other independent variables in the model than there is between these variables and the dependent variable (Cohen & Cohen, 1983; Krus & Wilkinson, 1986). These patterns of correlation can also be seen in Table 3 for the ELL and EL1 groups. To overcome this problem we re-specified the model without Grade 5 working memory, phonological awareness, and word reading fluency. Results are shown in Table 5.

As can be seen, altogether, 62% of the variance in ELL and 69% of the variance in EL1 was explained by the model. In the ELL group Grade 2 measures (all entered in the first block) explained 47% of the variance and Grade 5 predictors explained additional 15% of the variance in Grade 5 reading comprehension. The beta weights indicated that in the ELL group vocabulary and phonological awareness assessed in Grade 2 were strongly associated with Grade 5 reading comprehension. Of the Grade 5 predictors, non-verbal ability, word identification, syntax, listening comprehension, and text reading fluency, contributed uniquely to the prediction of Grade 5 reading comprehension. In the EL1 group Grade 2 measures (all entered in the first block) predicted 54% of the variance, and Grade 5 measures contributed additional 17% to reading comprehension. The beta weights indicated that, as was the case in the ELL group, Grade 2 vocabulary and phonological awareness were strongly associated with Grade 5 reading comprehension in the EL1 group. Of the Grade 5 predictors, in addition to non-verbal ability, accurate word reading, vocabulary, and text reading fluency contributed uniquely to the prediction of Grade 5 reading comprehension in this group.

The fact that none of the Grade 2 reading fluency measures was a significant predictor in the ELL and EL1 groups, and the positive and moderately high correlations among language and reading fluency measures suggested that text reading fluency captures to a large extent the ability to process linguistic information quickly, and that the language and text reading fluency measures share substantial amount of variance. To examine this possibility we ran additional multiple regression analyses in each language group where the fluency measures were entered prior to the language measures. However, in both ELL and EL1 groups the results remained unaltered.

In sum, vocabulary and phonological awareness were the early independent predictors (autoregressors) of Grade 5 reading comprehension in ELL and EL1 alike. As for the Grade 5 predictors the results point to two general observations. First, the variables that contributed unique variance to reading comprehension in Grade 5 in the presence of the Grade 2 autoregressors were similar but not identical in ELLs and EL1s. Second, some Grade 2 predictors that did not contribute independently to Grade 5 reading comprehension became significant when assessed in Grade 5, a result that is in line with the notion of change in the nature of the predictors between Grade 2 and Grade 5. This was the case with regard to word reading and text reading fluency that were significant in Grade 5 in both groups. In the case of the ELLs, but not with EL1s, this change was also noted with regard to two aspects of oral language proficiency (syntax and listening comprehension). Overall, a larger number of variables were significant predictors of reading comprehension in the ELL group than in the EL1 group.

Discussion

ELL–EL1 group similarities and differences

This study examined a number of related theoretical issues pertaining to the development of reading fluency and reading comprehension in ELLs and their monolingual EL1 counterparts. In general, we replicated the finding that the English language skills and reading comprehension of ELLs are significantly less well-developed than those of their monolingual counterparts. Importantly, in this study this lag was noted in the early school years and three years later, when these children reached upper elementary school. Specifically, we have shown that ELL–EL1 differences continue to exist on various aspects of English oral proficiency varying in unit size, including vocabulary breadth, overall command of a variety of syntactic skills, and comprehension of spoken language.

At the same time, ELLs are not at a disadvantage in comparison with their monolingual peers when it comes to their performance on basic underlying cognitive processes such as rapid automatized naming, phonological awareness, and working memory. Nor are the ELLs at a disadvantage in comparison with their monolingual peers with regard to accuracy and speed of grade appropriate, word-level reading skills. Relatedly, ELLs are not at a disadvantage when grade appropriate text reading fluency is considered, probably because the task demands for reading text fluently are not as complex as the demands required to comprehend text. At the same time it is important to recognize that text reading fluency is more complex than word-level reading as it requires the ability to integrate accurately and efficiently word-level reading skills and language skills. The results underscore the importance of considering the multidimensional and complex nature of the development of cognitive, language, and literacy skills of children who are schooled in the societal rather than the home language. After several years in the school system ELLs continue to lag behind their monolingual counterparts on complex language and reading comprehension tasks, even though they are able to perform at par on word-level reading, reading fluency, and cognitive component skills. ELLs are challenged by complex tasks such as reading for meaning in English, that require broad funds of knowledge and more advanced language skills. ELLs can benefit from instructional methods and programs designed to accelerate L2 language development.

The changing nature of reading fluency

By using grade appropriate texts we were able to demonstrate that regardless of language status, in the primary grades, word and text reading fluency are less differentiated, and that, indeed, they form a single factor. At this point both word and text reading fluency are primarily associated with basic word reading skills, and the focal skills that underlie the ability of monolingual and ELL students at the onset of schooling to read with fluency are word-level reading skills.

However, gradually, over the years, word and text reading fluency split into two distinct factors, one involving word reading fluency and the other involving text reading fluency. This split in the fluency construct reflects two concomitant developmental processes: word-level reading skills become more automatized, and text reading fluency becomes more aligned with language skills. In other words, children become more adept at executing automatically word-level reading skills, and at the same time it is reasonable to speculate on the basis of other research that their text reading fluency is enhanced by a growing ability to take advantage of top down processes and a growing repertoire of language skills.

In this study we have shown that individual differences in vocabulary knowledge are related to text reading fluency of ELLs and their monolingual counterparts, as are syntactic skills and a more global ability to comprehend oral discourse. All three aspects of language comprehension correlate positively and significantly with text reading fluency, suggesting that each of these skills plays an important role in text reading fluency. It is important to acknowledge that other aspects of oral language proficiency not assessed in this study such as morphological skills and the ability to process prosodic features may also be related to text reading fluency and should be studied in the future.

Beyond SVR: a complex view of reading comprehension in ELL and EL1

This study shows that it is possible to predict a substantial proportion of the variance in reading comprehension in the upper elementary level by considering jointly Grade 2 factors and factors whose role emerges more distinctly in later years. This general conclusion applies to school children regardless of language status, and in spite of the consistent gap that exists between ELLs and EL1s in their command of English oral language skills and reading comprehension. It is notable that a large proportion of the variance (62% and 69% in the ELL and monolingual groups, respectively) was explained by the model. Thus we see that in the ELL and EL1 groups alike individual differences in vocabulary breadth coupled with phonological awareness skills, assessed in Grade 2, are robust predictors of subsequent reading comprehension, and exert their role in a consistent manner regardless of language status. By upper elementary school, ELLs and EL1s have had the opportunity to develop further their literacy and language skills (and expand their background and strategic knowledge). At this stage, word reading and additional aspects of language comprehension, as well as reading fluency and naming speed emerge as concurrent predictors, whose role cannot be simply attributed to the Grade 2 autoregressors. Thus, by Grade 5 it is not simply phonological awareness but accuracy of word reading that is associated with reading comprehension in both groups. In the EL1 group vocabulary knowledge continues to be pivotal, but in the ELL group, it is not simply breadth of vocabulary knowledge but other aspects of English language proficiency such as syntactic knowledge and the ability to comprehend spoken language that augment the language comprehension cluster, and play an important role in reading comprehension. In both groups text reading fluency, an integrative and complex skill, that by Grade 5 captures the ability to process and synchronize quickly and efficiently print with various aspects of language, emerges as an important skill that contributes to reading comprehension. On the whole, reading comprehension of Grade 5 ELL and EL1 students benefits from a gradual build-up of accurate word-level reading skills, a gradual build-up of various language skills, the ability to process these word and language related skills with ease and fluency. It also includes ubiquitous, hard-wired, cognitive components such as rapid naming and non-verbal ability.

The fact that in the EL1 group syntactic knowledge and listening comprehension do not augment the oral language construct the way they do in the ELL group may appear unexpected. From a methodological perspective, this result may be related to the nature of the measures used to assess syntactic skills and listening comprehension, and the possibility that these two tasks were not as challenging for the EL1 participants as they were for the ELLs.

From a theoretical perspective, it is productive to consider the possibility that as their English language proficiency develops further, the ELLs begin to draw on more complex language skills that go beyond single word boundaries to assist them in processing text. In other words, of the various language components that comprise language proficiency, in the early years it is individual differences in vocabulary that predict reading comprehension in subsequent years. This finding suggests that early individual differences in vocabulary are stable, and perhaps for this reason individual differences in vocabulary skills in later years do not augment the prediction. The findings also suggest that with development and increased proficiency the nature of language proficiency of ELLs changes and that these changes cannot be simply attributed to the strength of correlations among parallel constructs of language proficiency administered three years apart. In these early years individual differences in syntactic skills and listening comprehension are not yet sufficiently differentiated to exert their role, but it appears that by Grade 5 these components of language proficiency become more developed and more differentiated, and their association with reading comprehension can be more easily discerned. Additional research in which the same syntactic and listening comprehension measures are used across times and with subgroups of readers is needed to replicate and substantiate this theoretical and developmental perspective of what constitutes L2 language proficiency and the manner in which it relates to discourse comprehension.

Taken together, these findings suggest a more nuanced understanding of early and later factors that enhance or impede reading comprehension in ELLs and EL1s. Vocabulary knowledge and phonological awareness are stable sources of individual differences that emerge as early predictors of subsequent reading comprehension of monolingual children and ELLs coming from a variety of linguistic and cultural backgrounds. At the same time, with development and schooling the nature of text reading fluency changes from the primary grades, where it draws primarily on word recognition skills to the upper elementary, where it draws more heavily on language skills. This change in the nature of reading fluency is associated with its emerging role as a predictor of reading comprehension. For ELLs, one notes as well an increasing role of aspects of language comprehension beyond vocabulary. Concomitant with a shift in the nature of English language proficiency that consists primarily of command of vocabulary in the primary grades to an increased ability to handle various grammatical structures, and in general, to comprehend spoken discourse in the upper elementary comes a larger contribution of these language components to reading comprehension.

Notes

The test–retest reliability coefficients reported here are based on the students’ performance in different years (i.e., Grades 2 and 5).

Note that at the time when this longitudinal study was launched standardized commercial measures of phonological processes (e.g., CTOPP) were not available.

References

Aarts, R., & Verhoeven, L. (1999). Literacy attainment in a second language submersion context. Applied Psycholinguistics, 20, 377–393.

Adlof, S. M., Catts, H. W., & Little, T. D. (2006). Should the simple view of reading include fluency component? Reading and Writing, 19, 933–958.

Al Otaiba, S., Petscher, Y., Pappamihiel, N. E., Williams, R. S., Drylund, A. K., & Connor, C. M. (2009). Modeling oral reading fluency development in Latino students: A longitudinal study across second and third grade. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 315–329.

Berninger, V. W., Abbott, R. D., Trivedi, P., Olson, E., Gould, L., Hiramatsu, S., et al. (2010). Applying the multiple dimensions of reading fluency to assessment and instruction. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 28, 3–18.

Biemiller, A. J. (1981). Biemiller test of reading processes. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

Cain, K., Oakhill, J., & Bryant, P. (2004). Children’s reading comprehension ability: Concurrent prediction by working memory, verbal ability, and component skills. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96, 31–42.

Carlisle, J. F., Beeman, M., Davis, H. L., & Spharim, G. (1999). Relationship of metalinguistic capabilities and reading achievement for children who are becoming bilingual. Applied Psycholinguistics, 20, 459–478.

Carver, R. P. (1997). Reading for one second, one minute, or one year from the perspective of rauding theory. Scientific Studies of Reading, 1, 3–43.

Catts, H. W., Fey, M. E., Zhang, X., & Tomblin, B. (1999). Language basis of reading and reading disabilities: Evidence from a longitudinal investigation. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3, 331–361.

Chall, J. S., Jacobs, V. A., & Baldwin, L. C. (1990). The reading crisis: Why poor children fall behind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Associates.

Cohen-Mimran, R. (2009). The contribution of language skills to reading fluency: A comparison of two orthographies for Hebrew. Journal of Child Language, 36, 657–672.

Collins, W. M., & Levy, B. A. (2008). Developing fluent text procession with practice: Meorial influences on fluency and comprehension. Canadian Psychology, 49(2), 133–139.

Crosson, A. C., & Lesaux, N. K. (2010). Revisiting assumptions about the relationship of fluent reading to comprehension: Spanish-speakers’ text-reading fluency in English. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 23, 475–494.

Cutting, L. E., Materek, A., Cole, C. A. S., Levine, T. M., & Mahone, E. M. (2009). Effects of fluency, oral language and executive function on reading comprehension performance. Annals of Dyslexia, 59, 34–54.

Cutting, L. E., & Scarborough, H. S. (2006). Prediction of reading comprehension: Relative on how comprehension is measured. Scientific Studies of Reading, 10, 277–299.

Denckla, M. B., & Rudel, R. G. (1976). Rapid automatized naming (R.A.N.): Dyslexia differentiated from other learning disabilities. Neuropsychologia, 14, 471–479.

Dunn, L., & Dunn, L. (1981). Peabody picture vocabulary test–revised. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Durrell, D. D. (1970). Durrell analysis of reading difficulty. New York: Psychological Corporation.

Francis, D. J., Fletcher, J. M., Stuebing, K. K., Lyon, G. R., Shaywitz, B. A., & Shaywitz, S. E. (2005). Psychometric approaches to the identification of LD: IQ and achievement scores are not sufficient. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38(2), 98–108.

Geva, E. (2006). Second-language oral proficiency and second-language literacy. In D. August & T. Shanahan (Eds.), Developing literacy in second-language learners: A report of the National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth (pp. 123–139). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Geva, E., Wade-Woolley, L., & Shany, M. (1997). Development of reading efficiency in first and second language. Scientific Studies of Reading, 1, 119–144.

Geva, E., & Yaghoub Zadeh, Z. (2006). Reading efficiency in native English-speaking and English-as-a-second-language children: The role of oral proficiency and underlying cognitive-linguistic processes. Scientific Studies of Reading, 10, 31–57.

Gottardo, A., & Mueller, J. (2009). are first and second language factors related in predicting school language reading comprehension? A study of Spanigh-speaking children acquiring English as a second language from first to second grade. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 330–344.

Hoover, W. A., & Gough, P. B. (1990). The simple view of reading. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 2, 127–160.

Hutchinson, J. M., Whiteley, H. E., Smith, C. D., & Connors, L. (2003). The developmental progression of comprehension-related skills in children learning EAL. Journal of Research in Reading, 26(1), 19–32.

Jenkins, J. R., Fuchs, L. S., van den Broek, P., Espin, C., & Deno, S. L. (2003). Sources of individual differences in reading comprehension and reading fluency. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 719–729.

Johnson, J. S., & Newport, E. L. (1989). Critical period effects in second language learning: The influence of maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language. Cognitive Psychology, 21, 60–99.

Joshi, R. M., & Aaron, P. G. (2000). The component model of reading: Simple view of reading made a little more complex. Reading Psychology, 21, 85–97.

Kame’enui, R. J., Simmons, D. C., Good, R. H., & Harn, B. A. (2000). The use of fluency-based measures in early identification and evaluation of intervention efficacy in schools. In M. Wold (Ed.), Time, fluency, and dyslexia (pp. 307–333). Parkton, MD: York Press.

Kirby, J. R., & Savage, R. S. (2008). Can the simple view deal with the complexities of reading? Literacy, 42, 75–82.

Krus, D. J., & Wilkinson, S. M. (1986). Demonstration of properties of a suppressor variable. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, 18, 21–24.

Lesaux, N. K., Rupp, A. A., & Siegel, L. S. (2007). Growth in reading skills of children from diverse linguistic backgrounds: Findings from a 5-year longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(4), 821–834.

Lesaux, N. K., & Siegel, L. S. (2003). The development of reading in children who speak English as a second language (ESL). Developmental Psychology, 39, 1005–1019.

Little, R. J. A., & Rubin, D. B. (2002). Statistical analysis with missing data (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

MacGinitie, W. H., & MacGinitie, R. K. (1992). Gates-MacGinitie reading tests (2nd Canadian ed.). Toronto, ON: Nelson.

Meyer, M. S., & Felton, R. H. (1999). Repeated reading to enhance fluency: Old approached and new directions. Annals of Dyslexia, 49, 283–306.

Nakamoto, J., Lindsey, K. A., & Manis, F. R. (2007). A longitudinal analysis of English language learners word decoding and reading comprehension. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 20, 691–719.

Perfetti, C. A. (1985). Reading ability. New York: Oxford University Press.

Perfetti, C. A. (2007). Reading ability: Lexical quality to comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 11, 357–383.

Puranik, C. S., Petscher, Y., Al Otaiba, S., Catts, H. W., & Lonigan, C. J. (2008). Development of oral reading fluency in children with speech or language impairments. A growth curve analysis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41, 545–560.

Raven, J. C., Court, J. H., & Raven, J. (1983). Manual for Raven’s progressive matrices and vocabulary scales: Section 4 advanced progressive matrices. London: Lewis.

Rosner, J., & Simon, D. P. (1971). The Auditory Analysis Test: An initial report. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 4, 383–392.

Samuels, S. J. (2002). Reading fluency: Its development and assessment. In A. E. Farstrup & S. J. Samuels (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (3rd ed., pp. 166–183). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Samuels, S. J., Schermer, N., & Reinking, D. (1992). Reading fluency: Techniques for making decoding automatic. In S. Samuels & A. Farstrup (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (pp. 124–144). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Schafer, J. L. (2000). NORM: Multiple imputation of incomplete multivariate data under a normal model (Version 2) [Computer software]. University Park: Pennsylvania State University, Department of Statistics.

Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147–177.

Schreiber, P. A. (1980). On the acquisition of reading fluency. Journal of Reading Behavior, 12, 177–186.

Schulz, K. F., Chalmers, I., Hayes, R. J., & Altman, D. G. (1995). Empirical evidence of bias: Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. Journal of the American Medical Association, 273, 408–412.

Semel, E., Wigg, E. H., & Secord, W. (1995). Clinical evaluation of language fundamentals-3. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Statistics Canada. (2001). Census of Canada topic based tabulations, immigration and citizenship tables: Immigrant status and place of birth of respondent, sex, and age groups, for population, for census metropolitan areas, tracted census agglomerations and census tracts, 2001 census (Catalogue number 95F0357XCB2001002).

Storch, S. A., & Whitehurst, G. J. (2002). Oral language and code-related precursors to reading. Evidence from a longitudinal structural model. Developmental Psychology, 38, 934–947.

Torgesen, J. K., Rashotte, C. A., & Alexander, A. (2001). Principles of fluency instruction in reading: Relationships with established empirical outcomes. In M. Wolf (Ed.), Dyslexia, fluency, and the brain (pp. 333–355). Parkton, MD: York Press.

Wechsler, D. (1991). Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (3rd ed.). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Whitehurst, G. J., & Lonigan, C. J. (1998). Child development and emergent literacy. Child Development, 69, 335–357.

Wiley, H. I., & Deno, S. L. (2005). Oral reading and maze measures as predictors of success for English learners on a state standards assessment. Remedial and Special Education, 26, 207–214.

Wilkinson, G. S. (1993). Wide Range Achievement Test–Revised (WRAT 3-R) (3rd ed.) . Wilmington, DE: Wide Range.

Wolf, M., & Katzir-Cohen, T. (2001). Reading fluency and its intervention. Scientific Studies of Reading, 5, 211–239.

Woodcock, R. W. (1987). Woodcock reading mastery test. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Geva, E., Farnia, F. Developmental changes in the nature of language proficiency and reading fluency paint a more complex view of reading comprehension in ELL and EL1. Read Writ 25, 1819–1845 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-011-9333-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-011-9333-8