Abstract

Purpose

The current study sought to review instruments measuring self-care for adolescents with health needs to provide a summary of the tools available for conducting self-care research in this population.

Method

Studies were mainly identified through searches in three electronic bibliographic databases (i.e., PsycINFO, CINAHL, and PubMed) and additional sources to retrieve relevant articles. Studies were included if they focused on self-care measures, included samples of adolescents (ages 10–19), were published in English peer-reviewed journals, dissertations, and from the years 1980 through 2020. The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) was used to assess the methodological quality of each study and evaluate the measurement quality based on available studies.

Results

A total of ten scales from 12 papers were identified to meet the search criteria and designed for adolescent patients with three types of health needs, including diabetes, cystic fibrosis, and others (female care and nutrition). There is a lack of a clear and comprehensive definition of self-care for different health needs. The dominant focus of the scales was the behavioral aspect of self-care (e.g., adherence to medication regimen), with only a few scales (e.g., female care) assessing the psychological aspect of self-care. The quality of the psychometric properties of the scales varied greatly.

Conclusions

Results highlighted the need for more research on developing and validating self-care measures for adolescents with health needs. The unique developmental characteristics of adolescents should be adequately considered, and the psychological aspect of self-care should be incorporated in measurement development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Plain english summary

Self-care is an important issue for individuals who have health needs. However, little is known regarding how to measure self-care among adolescents. In this study, we systematically reviewed self-care measures that were designed for adolescents with a variety of health needs, such as diabetes, cystic fibrosis, and female care. The results indicated that self-care is an emerging concept in healthcare research and at an early stage for its measurement research on adolescents. We summarized the key characteristics of available measures and suggested their utility in research and practice.

Introduction

The importance of self-care has long been recognized in healthcare fields, especially nursing and medicine, and in more recent decades, psychology. The concept of self-care has been evolving, and there has not been a universally accepted definition. Broadly speaking, self-care can be understood as “people being responsible for their own health and well-being” through behaviors or lifestyle that help them achieve this goal [1]. The most common definition of self-care used in the self-care measures and empirical studies typically refers to a set of behaviors aimed at attaining improved health for individuals, which are performed voluntarily by the individual on behalf of themselves [2]. Research has shown that self-care behaviors play a role in children’s health for those facing certain illnesses, such as diabetes [3] and cystic fibrosis [4]. As children grow, an ill child must also learn how to manage their health problem in addition to universal self-care, which may be complex and demanding. However, the completion of self-care encounters unique challenges during adolescence due to developmental factors such as rising risk-seeking behaviors [5, 6]. Unfortunately, the dominant focus of self-care research has been on adults and young children, largely neglecting the unique developmental characteristics of adolescents. Many measures were developed to assess self-care in adults with various illnesses, and some for non-patient adults or children, all of which have been summarized elsewhere [7,8,9]. To this date, no review is available with a focus on the measures to assess self-care among adolescents.

The current study provides a systematic review of the measures that purposefully assess self-care in adolescents with health needs, including reports of the theoretical foundation, key study characteristics, and psychometrics of the measure. We adopted the World Health Organization’s [10] definition of health needs, which states that “health needs are objectively determined deficiencies in health that require health care, from promotion to palliation”. According to this definition, health needs can be identified by health professionals to recognize the needs for health services “from the point of view of the benefit obtainable from advice, preventive measures, management, or specific therapy” and/or by scientific methods that confirm the needs for healthcare “by objective measures of biological, anthropometric, or psychological factors, expert opinion or the passage of time.” Generally speaking, individuals who have conditions that can be classified in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) have scientifically confirmed health needs [11]. Given the early stage of research on self-care, measures that are not associated with any diseases identified by ICD-11 but recognized as for people having needs for healthcare by professional opinions are also eligible for the review in this study. We aim to discern the gaps in self-care measurement research and suggest future directions to facilitate research on self-care to reduce health and behavioral risks and promote well-being among adolescents.

Given the focus on self-care for health needs in this review, it is necessary to differentiate self-care from a related but distinct construct—self-management. Self-management has a clearer and more narrow focus on one’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, and related consequences of chronic or acute health conditions, whereas self-care incorporates prevention of illness and accidents, the appropriate use of medicine and treatment of minor ailment, and broader health promotion in addition to self-management [1, 12]. Thus, self-management may be viewed as a subset of self-care [1]. More concept delineation between self-care and associated concepts, such as self-management and self-monitoring, can be found in two references [1, 12].

The Self-Care Deficit Theory [13] provided the most systematic understanding of what self-care means for people who have needs for managing acute and chronic illnesses so far [14]. The theory emphasizes two main components of self-care: (1) self-care agency, or the ability to engage in self-care behaviors, and (2) actual self-care behaviors [13]. Based on this theory, the goal of self-care for patients is to maintain an acceptable level of functioning, thus prevent illness or complications and promote health and well-being [15], and the key is patient’s ability to complete these behaviors. According to this theory, there are three types of self-care requisites: universal, developmental, and health-deviation [16]. Universal self-care behaviors refer to those processes that are essential to a healthy life, such as breathing, eating, social interaction, and physical activity. Developmental self-care focuses on needs that arise throughout the life cycle, such as adjusting to bodily changes. Health-deviation self-care behaviors focus on those actions necessary to manage a health problem (e.g., adherence to medication regimen). For patients, focus on universal and health-deviation self-care requisites is paramount, because both aim to treat the symptoms of health problems and to prevent worse outcomes in the future [2].

In comparison, developmental self-care requisites were only described briefly in the theory, and have received much less attention in research. Based on a nursing theory of self-care [16], self-care is a multi-faceted, higher-level function that is learned by the individual, directed toward a goal, and is comprised of purposeful and deliberate actions. Thus, an individual's knowledge, goals and motivation, and skills, many of which associate with developmental levels, are the fundamentals to carry out self-care. Seeing through a developmental lens, adolescence is a crucial stage for self-care development because this period is remarked by many changes in physiological, cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and social areas [17], and these changes distinguish adolescents’ needs for self-care, self-care agency, and behavior from those in children or adults. Notably, despite more advanced cognitive and physical development in adolescence, around the time of puberty, an overactive reward brain system and slow maturation of the cognitive-control system lead to difficulty in integrating cognition (e.g., thoughts, knowledge, beliefs) and behaviors as well as regulating behaviors that associate with risk (e.g., impulsivity, sensation–seeking) [5, 6]. These difficulties often result in behaviors that impose more of a risk on their safety, health, and development. In fact, adolescence is the period that the rate of risk-taking behavior increases, with some in more extreme forms that lead to severely detrimental consequences [18]. Besides the challenges and problems, it should also be noted that adolescence is a critical time during which young individuals develop their self-identity, values and beliefs, and behavioral habits, including self-care. Actively or passively, adolescents are learning knowledge and skills through experiences to form self-care-related agencies and behaviors, which can have a profound impact on one’s developmental trajectory into adulthood [19]. Thus, there is the need for studying self-care in adolescents with their developmental characteristics in mind. As an initial step drawing more attention to self-care research on adolescents from a developmental perspective, the present study aims to systematically review existing measures of self-care for adolescents with health needs.

Method

Search strategy

The protocol for this review complies with the latest Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Guidelines (PRISMA) [20]. The search terms were generated from scoping searches and were kept broad to capture all potentially relevant studies. The search terms focused on self-care measures. Databases were searched within the “keyword” and “abstract” fields, and search terms were combined with BOOLEAN operators (e.g., OR, NOT). The terms used were as follows: (“self-care” OR “self care”) AND (“scale,” OR “measurement,” OR “instrument,” OR “measure”), AND (“children,” OR “adolescents,” OR “adolescence,” OR “youth”). The year range specified for the search was 1980–2020, and the last searches were conducted in August 2020, using the following electronic bibliographic databases: PsycINFO, CINAHL, and PubMed. Titles and abstracts were examined to identify relevant studies for inclusion in the review. The references cited in selected papers were also used to identify additional papers. Several articles were not available from the databases but obtained through additional search tools, including Google Scholar, an interlibrary loan service, or the instrument’s developer.

Eligibility criteria

The search was limited to empirical studies published in English or translated to English in peer-reviewed journals, dissertations, or Masters’ Theses. Non-peer-reviewed sources were excluded. Other inclusion criteria include being published between the years of 1980 and 2020 and using adolescent samples (ages 10–19) [21], either specifically (i.e., adolescent age range only) or inclusively (beyond adolescence but including adolescents). Papers reporting the development and/or validation of a self-care instrument were included. Studies were excluded if they (1) did not explicitly assess self-care but related constructs (e.g., self-management or self-efficacy), (2) did not focus on individuals with health needs (by the WHO definition relying on health professionals’ recognition and/or scientific methods) [10], and (3) only had narrative descriptions without any quantitative testing data. Two reviewers who received doctoral-level research training read all the titles and abstracts to assess the eligibility of the studies. Then full manuscripts were retrieved for the identified studies, and the reviewers evaluated their eligibility independently. Disagreements were resolved by a panel discussion among the first author and two reviewers.

Search outcome

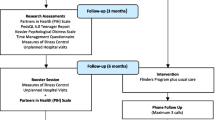

There were 16,115 articles yielded from the initial search from all three databases. After the removal of duplicate articles when comparing databases, there were 13,678 articles left to review. The initial screening was conducted by examining the abstract and keyword options within the databases to limit the relevance to self-care, which yielded 495 articles. Then the reviewers screened the full text, specifically the abstracts, methods, and results sections, and references of these articles to select studies that contained a self-care instrument (N = 60). This included nine original studies retrieved through an interlibrary loan system, author contact, or Google Scholar. For these 60 articles, the reviewers examined the full texts using the full search criteria and excluded 48 studies that did not measure the self-care construct and did not include development or validation of the instrument, or the age range of the sample did not include adolescents (ages 10–19). Finally, 12 papers with ten instruments were identified for the systematic review. The flow diagram in Fig. 1 shows the overall search process. Figure 2 demonstrates the full search strategy using the PsycINFO database.

Quality assessment of the included studies and measures

The methodological quality of each study was assessed using the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement Instruments (COSMIN; https://www.cosmin.nl/) checklist. This checklist was developed to determine whether a study on measurement properties of a self-reported instrument meet methodological quality standards [22]. There was a list of items associated with the study design and each property assessment. The study was rated as very good, adequate, doubtful, inadequate, or does not apply to each item. The checklist was also used to evaluate the following measurement properties demonstrated in each study: internal consistency, reliability, content validity, structural validity, hypotheses testing (as a proxy for criterion validity), and cross-cultural validity. Due to a lack of gold standards for self-reported self-care instruments, criterion validity was not rated, as recommended by the COSMIN panel, and the comparison with another instrument was considered hypothesis testing [23]. The measurement error and responsiveness properties were omitted in the result table because they were not evaluated in any studies.

The overall quality of the results for each psychometric property was rated as Poor, Fair, Good, and Excellent. The quality criteria were adapted based on those used in Matarese, Lommi, and De Marinis’s review [8] to evaluate the measurement properties (see Supplementary Appendix B). To generate the overall rating for each measurement property, the lowest rating assigned to any item in the COSMIN checklist was primarily considered. For example, if one item in the checklist related to structural validity is rated as poor, the overall methodological quality of the structural validity is rated as poor. Two reviewers independently rated each study. The ratings were compared, discussed, and a third reviewer (the first author) was consulted to resolve any discrepancies.

Planned risk of bias and data abstraction

Hawker et al. [24] quality appraisal tool was used to assess the risk of bias at the study level, including potential limitations or methodological weaknesses. Each study was assessed on nine components (abstract and title, introduction and aims, method, data analysis, ethics and bias, results, generalizability, and implications).

The following data were extracted independently by two reviewers for each article and reported in a pre-designed table: instrument’s name, theoretical basis, factor structure, study characteristics (e.g., sample size, age range, country, and language), number of items, response options, study author(s), year of publication, and validity and reliability properties. The extracted data were examined for key results in that study, or across multiple studies in order to draw conclusions based on the consistency of findings.

Planned synthesis of results

The measurement properties for each instrument were synthesized, and the number of validity studies was taken into account to classify the methodological quality [22]. Specifically, the degree of evidence (positive or negative) for an instrument is decided following the guidelines: (1) evidence is considered strong when consistent findings were derived by one study of excellent methodological quality, or by at least two studies of good methodological quality; (2) evidence is moderate when consistent findings were derived by one study of good methodological quality or by at least two studies of fair methodological quality; (3) evidence is limited when findings were derived by one study of fair methodological quality; (4) evidence is conflicting when findings reported across two or more studies were conflicting; and (5) evidence is unknown when findings were derived only by studies of poor methodological quality. Two reviewers independently assessed each instrument for their methodological quality and solved any differences by discussion.

Results

The search yielded 10 instruments developed for adolescents with health-related issues in total. Major characteristics of all reviewed scales are displayed in Table 1. The measurement psychometric properties are shown in Table 2. Three distinct types of healthcare issues were found and used to categorize the measures, including Diabetes (N = 5), Cystic Fibrosis (N = 2), and Others (Female care, N = 2; Nutrition, N = 1). Due to the space limit, the narrative description of the individual measures is in the appendix.

Risk of bias within studies

Hawker et al.’s [24] quality appraisal tool was applied to assess risk of bias and quality assessment. Most included studies had clear titles, abstracts, and introductions, as well as clearly reported the analyses conducted and results found. For most scales, there was only one study examining the measurement quality. Some studies omitted key method information, such as the age range or average age of the sample. More recently published studies (i.e., after 2000) tended to have higher quality of the evaluation. However, the quality assessment findings suggested that bias likely existed in most included studies, due to non-representative sampling and the study design that was not able to control or rule out confounding factors. However, given the fact that most of these studies were the initial or early development and validation of the scales, such limitations in the methods are understandable. Researchers should be aware of the possible bias and conduct further validation studies to reduce bias. The integrative results are presented below. The narrative results of each measure are available in the supplemental materials (Supplementary Appendix A).

Synthesis of the results

Most scales measuring self-care practices were conducted and published in the nursing or health care research field, followed by pediatric and/or clinical psychology. Of the scales presented, diabetes researchers had developed the highest number of self-care scales (N = 5), though the concept of self-care appeared to be largely limited to treatment adherence behaviors. Orem’s self-care deficit theory in nursing literature [13], is the most well-developed theory of self-care thus far, but for adolescent self-care measures, it was used as a foundation in two measures [25, 26]. No other theory was mentioned.

This review used the COSMIN criteria to rate the methodological quality of each study and the level of evidence of each measurement property [22]. A majority of the scales only have one validation study published, though the scales might have been used in other hypothesis testing studies. Overall, the types of psychometric properties evaluated per instrument varied greatly (see Table 2 for details). Internal consistency was the most commonly reported reliability, with most scales rated as having fair to excellent internal consistency based on the found studies. Test–retest reliability was reported for more than half of the measures (N = 6), ranging from fair to excellent. Inter-rater reliability was examined for one of the three scales that have adolescent and parent report forms, and the result was poor (Self-Care Inventory) [3]. Another scale has adolescent and parent reports (PDRQ) [27], though the consistency between the two forms was not tested. Among a total of 12 studies evaluated for measurement properties, eight studies had fair to excellent evidence for content validity, and nine studies reported fair to excellent evidence for structural validity. The most frequently evaluated validity measurement properties were construct or structural validity and criterion validity. Construct or structural validity was most commonly evaluated through Exploratory Factorial Analysis, followed by Confirmatory Factorial Analysis. The evidence for construct validity was widely mixed, ranging from fair to excellent. Hypothesis testing results offered a proxy for criterion validity, which was rated as good or excellent for approximately half of the studies. A majority of the scales were developed and validated in the United States, but a few were initially developed in other countries (i.e., the Revised-Diabetes Self-Care Inventory in Japan [28]; the Female Adolescents’ Sexual Reproductive Self-Care Scale in Iran [29]; the Adolescent Dysmenorrhic Self-Care Scale in Taiwan and Hong Kong [25, 30]). Evidence for cross-cultural validity was found for two instruments, including the Adolescent Dysmenorrhic Self-Care Scale (Taiwan, [25]; Hong Kong, China, [30]) and the Adolescent Nutrition Self-Care Questionnaire and the Parent Nutrition Dependent-Care Questionnaire (in the USA and Nicaragua, [26]).

Discussion

To gain a clear understanding of the availability of self-care measures for adolescents with health needs, this study provided a systematic review using a multidisciplinary approach, including three major databases and followed a comprehensive review guideline. In total, ten scales from 12 studies were found to meet all the search criteria. Overall, self-care is heavily studied in nursing, followed by pediatric and clinical psychology. Most scales presented moderate evidence for the reliability and validity of the scales. The conceptualization of self-care has primarily focused on observable behaviors (e.g., physical habits). In more recently published papers, such as those that examined self-care in female adolescents, the conceptualization of self-care was expanded into the psychological and ecological domains (e.g., self-control, family interaction). A lack of a sound theoretical framework to guide adolescent self-care assessment is evident, suggesting an early stage of research in this area.

Psychometric properties

In general, scales developed after 2000 demonstrated better psychometric properties. The measure with the most sufficient evidence supporting the psychometrics is the Pediatric Diabetes Routines Questionnaire for Adolescents [27], though additional validation studies are needed to assess its inter-rater reliability and cross-cultural validity. For other scales, the evidence is weak or inconsistent across studies or psychometric properties and warrant further improvement. Based on the results of our review, we recommend the following scales to assess self-care for adolescents with (1) Diabetes, Pediatric Diabetes Routines Questionnaire—Adolescent and Parent Forms [27], (2) Cystic Fibrosis, the Self-Care Independence Scale [4], and (3) need for female care, Adolescent Dysmenorrhic Self-Care Scale [25] and the Female Adolescents’ Sexual Reproductive Self-Care Scale [29]. However, we suggest that researchers use these measures with caution and should further validate these measures to ensure the appropriateness of their application in studies.

Developmental and contextual considerations in self-care conceptualization

Though the Self-care Deficit Theory in nursing was applied in two studies, it did not appear to provide a strong foundation for adolescent self-care, due to its weak focus on development. Among most studies, the definition of self-care is very behavioral and practice driven (e.g., physical habits and daily routines). In diabetes research, in particular, there is vague differentiation between self-care behavior and self-management or self-monitoring behavior with regimen adherence and symptom control as the goals. The behavioral focus in the scale content largely neglected the necessity of taking adolescents’ cognitive and psychological development into account, which introduces both advancement and risk in carrying out care for themselves. For instance, compared to children, adolescents’ cognitive and physical development enable them to better understand the importance of self-care and complete self-care tasks more independently. However, they also tend to experience more stress and have difficulty regulating emotions, cognition, and behaviors in a coherent manner [5, 6], which may undermine the actual action of self-care. Thus, adolescents’ awareness and evaluation of the psychological aspects of self-care should be among important dimensions of self-care assessment. The scales developed for female care (i.e., Dysmenorrhic Self-Care [25, 30]. Sexual Reproductive Self-Care [29]) did a good job in incorporating cognitive and psychological factors. The factors included but were not limited to expression of emotions, self-control, and knowledge or searching for knowledge.

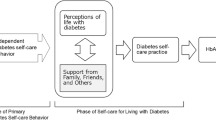

In addition, the two female care scales adopted an ecological view of self-care, which recognized the importance of the contextual factors, especially the parents’ influence (e.g., Adolescent and family interaction, Parent-adolescent communication barriers). This ecological view was also partially endorsed in the newest diabetes self-care scale (Revised—Diabetes Self-Care Inventory [28]), in this search, as it measured support from family and at school and discussions with medical staff/teachers. These findings indicated an emerging trend to incorporate an ecological view in the conceptualization of adolescent self-care and expanded domains of interpersonal interactions (e.g., adolescents and parents) in the measurement. Research in this area is promising, and we encourage more efforts in furthering our understanding of self-care in adolescents’ ecological systems.

Overall, the psychological aspect of self-care and the ecological factors associated with self-care have gained initial recognition beyond the behavioral aspect of self-care and sole intrapersonal focus of self-care. More research is needed, though, to capture the developmental characteristics of adolescents in defining, assessing, and promoting self-care and differentiating the possible differences across early, middle, and late adolescence.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically evaluate the self-care instruments for adolescents with health needs. Three major databases were used to include different health-related research fields (e.g., medicine, nursing, psychology) to yield optimal results. The COSMIN checklist, a systematic review guideline was followed to ensure the appropriateness and comprehensiveness of the evaluation of the search results. This review compiled available self-care instruments for adolescents and provided guidelines for the use of those instruments for researchers and clinicians alike. The review findings should help researchers improve existing measures or design new ones [31].

While the findings provide valuable information to research on self-care among adolescents, there are limitations to the current study. We considered it appropriate to use only the term “self-care” because the purpose of this review is to reveal the current stage of self-care research from an assessment perspective. However, exclusion of terms related to self-care might leave out other measures with self-care being embedded under a different construct name or phrase. Also, search filters were used to refine results by allowing the search terms to appear in the title or abstract rather than the full text, which might exclude some results. In addition, though we used three major databases to retrieve articles, employing more databases might reveal additional studies. Also, the article selection was limited to those published in English; hence, we might have overlooked instruments developed and evaluated in other languages and cultures and published in other languages without English abstracts in the searched databases.

Conclusion and future directions

This systematic review identified ten measures assessing self-care among adolescents with diverse health needs. Orem’s Self-Care Theory [32] is the theoretical foundation for a few identified instruments; particularly those developed for adolescents with female care needs and nutrition monitoring needs. No self-care instrument has reports of strong evidence for all the measurement properties, but several have good to excellent properties across multiple domains and are recommended for future research and practice use.

Although limitations were present in this study, the findings helped reveal a major gap in self-care measures for adolescents with health needs and lead to future directions pertinent to the growth of literature for the target population. Further evaluation is needed for psychometric properties of almost all existing instruments so that they can be appropriately used in practice and research. There is a need for an updated measure of self-care among adolescents as more than half of the included studies were published more than ten years ago. As self-care research expands to other fields, there is a need for assessing self-care beyond physical illness management, but also mental or behavioral care. Insufficient instruments in fields outside of nursing might contribute to a lack of visibility and knowledge of self-care, which is seldom taken into account in healthcare organizations and health policy decisions [33, 34]. We call for more research on adolescent self-care, with expanded and enriched conceptualization (e.g., not limited to the behavioral aspect of self-care, but also the psychological aspect, and incorporate the contextual factors through an ecological view of self-care), starting from developing and validating measures in other disciplines, such as health, clinical, school, and developmental psychology.

References

Wilkinson, A., & Whitehead, L. (2009). Evolution of the concept of self-care and implications for nurses: a literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(8), 1143–1147.

Sidani, S. (2011). Self-care. In Doran D. M. (Ed.), Nursing outcomes: the state of the science (2nd ed.) (pp. 79–124). Sudbury: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Lewin, A. B., La Greca, A. M., Geffken, G. R., Williams, R. B., Duke, D. C., Storch, E. A., & Silverstein, J. H. (2009). Validity and reliability of an adolescent and parent rating scale of type 1 diabetes adherence behaviors: the self-care inventory (SCI). Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34, 999–1007.

Patton, S. R., Graham, J. L., Varlotta, L., & Holsclaw, D., Jr. (2003). Measuring self-care independence in children with cystic fibrosis: the self-care independence scale (SCIS). Pediatric Pulmonology, 36, 123–130.

Galvan, A., Hare, T., Voss, H., Glover, G., & Casey, B. J. (2007). Risk-taking and the adolescent brain: who is at risk? Developmental Science, 10, F8–F14.

Steinberg, L. (2007). Risk taking in adolescence: new perspectives from brain and behavioral science. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 55–59.

Caro-Bautista, J., Martín-Santos, F. J., & Morales-Asencio, J. M. (2014). Systematic review of the psychometric properties and theoretical grounding of instruments evaluating self-care in people with type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70, 1209–1227.

Matarese, M., Lommi, M., & De Marinis, M. G. (2017). Systematic review of measurement properties of self-reported instruments for evaluating self-care in adults. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(6), 1272–1287.

Urpí-Fernández, A., Zabaleta-Del-Olmo, E., Montes-Hidalgo, J., Tomás-Sábado, J., Roldán-Merino, J., & Lluch-Canut, M. (2017). Instruments to assess self-care among healthy children: a systematic review of measurement properties. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73, 2832–2844.

Health needs. (n.d.). In World Health Organization Health Systems Strengthening Glossary. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/healthsystems/hss_glossary/en/index5.html

World Health Organization (2020). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). https://icd.who.int/

Richard, A. A., & Shea, K. (2011). Delineation of self-care and associated concepts. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 43(3), 255–264.

Orem, D. E. (1995). Nursing: concepts of practice (5th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

Hanson, C. L., De Guire, M. J., Schinkel, A. M., Kolterman, O. G., Goodman, J. P., & Buckingham, B. A. (1996). Self-care behaviors in insulin-dependent diabetes: evaluative tools and their associations with glycemic control. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 21, 467–482.

Sidani, S., & Doran, D. (2014). Development and validation of a self-care ability measure. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 46, 11–25.

Orem, D. E. (2001). Nursing: concepts of practice (6th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

Steinberg, L., & Morris, A. S. (2001). Adolescent development. Annual Reviews Psychology, 52, 83–110.

Kann, L., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Queen, B., & Lim, C. (2018). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 67(8), 1.

McCaleb, A., & Cull, V. V. (2000). Sociocultural influences and self-care practices of middle adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 15, 30–35.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151, 264–269.

Irwin, C. E., Burg, S. J., & Cart, C. U. (2002). America’s adolescents: where have we been, where are we going? Journal of Adolescent Health, 31, 91–121.

Terwee, C. B., Mokkink, L. B., Knol, D. L., Ostelo, R. W., Bouter, L. M., & de Vet, H. C. (2012). Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Quality of Life Research, 21, 651–657.

Mokkink, L. B., Terwee, C. B., Knol, D. L., Stratford, P. W., Alonso, J., Patrick, D. L., & De Vet, H. C. (2010). The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 10(1), 22.

Hawker, S., Payne, S., Kerr, C., Hardey, M., & Powell, J. (2002). Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qualitative Health Research, 12(9), 1284–1299.

Hsieh, C.-H., Gau, M.-L., & G., Mao, H-C, & Li, C-Y. (2004). The development and psychometric testing of a self-care scale for dysmenorrhic adolescents. The Journal of Nursing Research, 12(2), 119–130.

Moore, J. B., Pawloski, L., Baghi, H., Whitt, K., Rodriguez, C., Lumbi, L., & Bashatah, A. (2005). Development and examination of psychometric properties of self-care instruments to measure nutrition practices for English and Spanish speaking adolescents. Self-Care, Dependent-Care, and Nursing: The Official Journal of the International Orem Society, 13,(1), 9–16.

Pierce, J. S., Jordan, S. S., & Arnau, R. C. (2018). Development and validation of the pediatric diabetes routines questionnaire for adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 26, 47–58.

Nakamura, N., Yakushijin, Y., Kanamaru, T., Tani, H., Ideno, K., & Nakai, A. (2019). Development and validity testing of the revised diabetes self-care inventory for children and adolescents. Diabetology International, 10, 117–125.

Alimoradi, Z., Kariman, N., Ahmadi, F., Simbar, M., & AlaviMajd, H. (2019). Development and psychometric properties of the female adolescents’ sexual reproductive self-care scale. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2018-0116

Wong, C. L., Ip, W. Y., Choi, K. C., & Lam, L. W. (2015). Examining self-care behaviors and their associated factors among adolescent girls with dysmenorrhea: an application of Orem’s self-care deficit nursing theory. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 47(3), 219–227.

Streiner, D. L., & Kottner, J. (2014). Recommendations for reporting the results of studies of instrument and scale development and testing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70, 1970–1979.

Orem, D. E. (1991). Nursing: Concepts of Practice (4th ed.). St Louis: Mosby.

Dubois, C. A., D’Amour, D., Pomey, M. P., Girard, F., & Brault, I. (2013). Conceptualizing performance of nursing care as a prerequisite for better measurement: a systematic and interpretive review. BMC Nursing, 12, 7.

Kennedy, M. A., & Hannah, K. (2007). Representing nursing practice: evaluating the effectiveness of a nursing classification system. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 39, 58–79.

Saucier, C. P. (1984). Self concept and self-care management in school-age children with diabetes. Pediatric Nursing, 10(2), 135–138.

Lancaster, B. M. (2006). Examination of the impact of age, family conflict, and perceived parental involvement on treatment adherence for children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis and diabetes. Dissertation (publication No.3243319). [Doctoral dissertation, Western Michigan University] ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Wong, C. L., Ip, W. Y., & Shiu, T. Y. (2012). Translation and validation of the Chinese-Cantonese version of the Exercise of Self-Care Agency Scale. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(9), 1122–1137.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a grant from the University of Memphis College of Arts and Sciences Research Grant Fund. This support does not necessarily imply endorsement by the University of research conclusions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors do not have conflicts of interest in this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, X., Walker, K. & Topps, A.K. A systematic review of self-care measures for adolescents with health needs. Qual Life Res 30, 967–981 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02685-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02685-1